0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Challenge was the tenth and final Bulldog Drummond novel. When Colonel Henry Talbot summons Bulldog Drummond and Ronald Standish, it is to inform them of the mysterious death of one of their colleagues, a millionaire. There was no sign of any wound, no trace of any weapon when they found him. What strikes Drummond and Standish is why a millionaire would have been travelling on the same boat - arguably the most uncomfortable crossing he could choose and very out-of-character.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

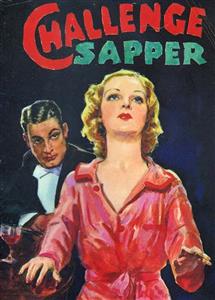

Challenge

by Sapper (H. C. McNeile)

First published in 1937

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Challenge

by

Sapper

I: The Game Begins

Colonel Henry Talbot, C.M.G., D.S.O., pushed back his chair and rose from the dinner table. His wife had gone to the theatre, so that he was alone. And on that particular evening the fact caused him considerable relief. The lady of his bosom was no believer in the old tag that silence is golden.

He crossed the hall and entered his study. There he lit a cigar, and threw his long, spare form into an easy chair. From the dining–room came the faint tinkle of glass as the butler cleared the table; save for that and the ticking of a clock on the mantelpiece the flat was silent.

For perhaps ten minutes he sat motionless staring into the fire. Then he pulled a sheet of paper from his pocket and studied the contents thoughtfully, while a frown came on his forehead. And quite suddenly he spoke out loud.

"It can't be coincidence."

A coal fell into the grate, and as he bent over to replace it, the flames danced on his thin aquiline features.

"It can't be," he muttered.

The clock chimed nine, and as the final echo died Sway a bell shrilled out. Came a murmur of voices from the hall; then the butler opened the door.

"Captain Drummond and Mr. Standish, sir."

Colonel Talbot rose, as the two men came into the room.

"Bring the coffee and port in here, Mallows," he said. "I take it you two fellows have had dinner?"

"We have, Colonel," said Drummond, coming over to the fire. "And we're very curious to know the reason of the royal command."

"I hope it wasn't inconvenient to either of you?" asked the colonel.

"Not a bit," answered Standish. "Not only are we curious, but we're hopeful."

The colonel laughed; then he grew serious again.

"You've seen the evening papers, I suppose."

"As a matter of fact I haven't," said Drummond. "Have you, Ronald?"

"I only got back to London at eight," cried Standish. "What's in 'em?"

There was a short pause; then Colonel Talbot spoke deliberately.

"Jimmy Latimer is dead."

"What!" The word burst simultaneously from both his listeners. "Jimmy—dead! How? When?"

"Put the tray on my desk, Mallows," said the colonel. "We'll help ourselves."

He waited until the butler had left the room; then standing with his back to the fire he studied the faces of the two men who were still staring at him incredulously.

"A month ago," he began, "Jimmy put in for leave. Well, you two know what our leave frequently covers, but in this case it was the genuine article. He was going to the South of France, and there was no question of work. I got a letter from him about a fortnight ago, saying he was having a damned good time, and that he'd made a spot of cash at Monte. He also implied that there was a pretty helping him to spend it.

"Last night, about ten o'clock, I got a call through here to my flat from Paris. Jimmy was at the other end. He told me he was on the biggest thing he'd ever handled—so big that he could hardly believe it himself. He was catching the eight–fifty–seven from the St. Lazare Station and crossing via Newhaven. It arrives at Victoria at six o'clock in the morning, and he was coming direct to me here. Couldn't even wait till I got to the office.

"As you can imagine, I wondered a bit. Jimmy was not a man who went in off the deep end without a pretty good cause. So I ordered Mallows to have some breakfast ready, and to call me the instant jimmy arrived. He never did; when the boat reached Newhaven he was dead in his cabin."

"Murdered?" asked Standish quietly.

"My first thought, naturally, when I heard the news," said the colonel. "Since then we've obtained all the information available. He got on board the boat at midnight, and had a whisky and soda at the bar. Then he turned in. He was, apparently, in perfect health and spirits, though the steward in the bar seems to have noticed that he kept on glancing towards the door while he was drinking. Ordinarily that is a piece of evidence which I should discount very considerably. It is the sort of thing that, with the best will in the world, a man might imagine after the event. But in this case he actually mentioned the fact to his assistant last night. So there must have been something in it. And the next thing that was heard of the poor old boy was when his cabin steward called him this morning. He was partially undressed in his bunk, and quite dead.

"When the boat berthed, the police were of course notified. Inspector Dorman, who is an officer of great ability, was in charge of the investigation, and very luckily he knew Jimmy and Jimmy's job. So the possibility of foul play at once occurred to him. But nothing that he could discover pointed to it. There was no sign of any wound, no trace of any weapon. His kit was, apparently, untouched; his money and watch were in the cubby–hole beside the bunk. In fact, everything seemed to indicate death from natural causes.

"But Dorman was not satisfied; there still remained poison. But since that would necessitate a post–mortem, and it was clearly impossible to keep the passengers waiting while that was done, he sent one of his men up in the boat–train with instructions to get everybody's name and address. Meanwhile he had the body taken ashore, and got in touch with a doctor. Then he went on board again, and cross–examined everybody who could possibly throw any light on it.

"He drew blank. Save for the one piece of evidence of the bar steward which I have already told you, no one could tell him anything. One sailor thought he had seen someone leaving Jimmy's cabin at about one o'clock, but when pressed he was so vague as to be useless. And so finally Dorman gave it up, and taking all the kit out of the cabin, he sat down to await the doctor's report."

The colonel pitched the stub of his cigar into the fire.

"Once again, blank. There was no trace of any poison whatsoever. The contents of the stomach were analysed; all the usual tests were done. Result—nothing. The doctor was prepared to swear that death was natural, though he admitted that every organ was in perfect condition."

"I was just going to say," remarked Drummond, "that I've seldom met anybody who seemed fitter than Jimmy."

"Precisely," said the colonel.

"What do you think yourself, sir?" asked Standish quietly.

"I'm not satisfied, Ronald. I know that the idea of poisons that leave no trace is novelist's gup; I admit that on the face of it the doctor must be right. And still I'm not satisfied. If what that barman said is the truth Jimmy was afraid of being followed. We know that he was on to something big; we know that his health was perfect. And yet he dies. It can't be coincidence, you fellows."

"If it is it's a very strange one," agreed Standish.

"And if it isn't it must be murder. And if it was murder, the murderer was on board. Have you a copy of the list of the passengers?"

Colonel Talbot walked over to his desk and handed Standish a paper.

"As you will see," he remarked, "the boat was very empty. Most of the passengers were third class."

"It's not a particularly popular boat, I should imagine," said Drummond. "I mean I can't see anybody who hadn't got to, for economy or some other reason, crossing by that route."

"Precisely," remarked the colonel gravely, and the two men looked at him.

"Something bitten you, Colonel?" cried Drummond. "Something so fantastic, Hugh, that I almost hesitate to mention it. But it was because what you have just said had struck me also that this wild idea occurred to me. Run your eye down the list of first class passengers—there are only eight—and see if one name doesn't strike you."

"Alexander; Purvis; Reid; Burton…Charles Burton. The millionaire bloke who throws parties in Park Lane…Is that what you mean?"

Colonel Talbot nodded.

"That is what I mean."

"But, damn it, Colonel, what on earth should he want to murder Jimmy for?"

"Not quite so fast, Hugh," said the other. "As I said, the idea may be fantastically wrong. But we've all heard of Charles Burton. We all know that even if he isn't a millionaire he's extremely well off. But who is Charles Burton?"

"I'll buy it," said Drummond.

"So would most people. Where does Charles Burton get his money from?"

"I gathered he was something in the City."

"Which covers a multitude of sins. But to cut the cackle, his name jumped at me out of that list. Why on earth should a man of his position and wealth choose one of the most uncomfortable Channel crossings to come over by?"

"It's a goodish step from that to murder," said Standish.

"Agreed, my dear fellow. But sitting in my office this afternoon, the question went on biting me. And at length I could stand it no longer. So I rang up the Sûreté in Paris, and asked them if they could find out in what hotel he was staying. Of course I knew he'd left, but that didn't matter. A short while after they got back to me to say that he had been staying at the Crillon, but had left for England last night. So I got through to the Crillon, where I discovered that Mr. Charles Burton had intended to fly over to–day, but that he had suddenly changed his mind yesterday evening, and decided to go via Newhaven and Dieppe."

"Strange," said Standish thoughtfully. "But it's still a goodly step, Colonel."

"Again agreed. But having started I went on. And by dint of discreet enquiries one or two small but interesting facts came to light. For instance, I gathered that on his frequent journeys to the Continent, he always flies. He loathes trains. I further gathered, or rather failed to gather, from various men I rang up, what his business was. He has an office, and the nearest I could get to it was that he was something in the nature of a financial adviser, whatever that may be. No one seemed to know who he was or where he came from. It seems he just blossomed suddenly about two years ago. One day he was not; the next day he was. But the most interesting point of all was a casual remark I heard in the club this evening. His name cropped up and somebody said: 'I sometimes wonder if that man is English.' I docketed that for future reference."

"Look here, Colonel," cried Drummond. "Let's get this straight. You started off by saying your idea was fantastic, but unless I'm suffering from senile decay, you're playing with the theory that Jimmy was murdered by Charles Burton."

"You could not have expressed it better. Playing with the theory."

"And you want us to play too?"

"If you've got nothing better to do. I haven't a leg to stand on; I know that. But Jimmy, who was in possession of very important information, died. Travelling in the same boat was a man whose origin is, to say the least, not an open book. Further, a man who, if he did change his habitual method of transport, would surely choose the Golden Arrow. I remember what you two did," he continued, "when that Kalinsky affair was on, over Waldron's gas and Graham Caldwell's aeroplane. You were invaluable, and this may be a case of the same type. You both of you go everywhere in London; all I'm asking you to do is to—"

"Cultivate Mr. Charles Burton," said Drummond with a grin.

"Exactly, Hugh. For if there is anything in my suspicions, I think you two, acting unofficially, are far more likely to get to the bottom of the matter—or at any rate to get on the trail—than I am through official channels."

"It's a date, Colonel," cried Standish. "But before we push off there are one or two points I want to get clear. In the letter you got from Jimmy a fortnight ago was there any hint he was on to something?"

"None at all."

"Have you heard from him since?"

"Not until he telephoned yesterday."

"So you don't know when he left the Riviera?"

"Not got the ghost of an idea. But we could find that out by wiring the hotel."

"Which was?"

"The Metropole at Cannes."

"I wish you would find out, Colonel. In your position you can do so more easily than we can, and it's information that may prove important."

"I'll wire or 'phone to–morrow, Ronald."

"Just one thing more. I assume some reliable person has gone through his kit and papers with a fine–tooth comb?"

"Dorman himself. There was nothing; nothing at all. But if our wild surmise is correct that is what one would have expected, isn't it? The murderer had plenty of time to examine all the kit himself."

"True," agreed Standish. "And yet a wary bird like poor old Jimmy has half a dozen tricks up his sleeve. Shaving soap; tooth paste…"

"I know Dorman. He's up to every trick himself. And if he says there's nothing there—then there is nothing."

"By the way," put in Drummond, "was Jimmy engaged?"

"Not that I've ever heard of."

"Who is his next of kin?"

"His father—Major John Latimer. Lives at his club—the Senior Army and Navy."

"A widower?"

"Yes. His wife died about three years ago." Drummond rose and stretched himself.

"Well, Ronald, old son, it seems to me that we've been handed out what dope there is. Let us go and kiss dear Charles good night."

"One second, Hugh," said Standish. "I suppose you've got no idea, Colonel, what tree Jimmy was barking up?"

"Absolutely none. It may be a spy organisation; it may be a drug gang; it may be anything. But whatever it is, it's something big or Jimmy wouldn't have said so."

"No hint, of course, of the possibility of foul play will appear in the papers?"

"Good Heavens! no," cried Colonel Talbot. "No hint, in fact, that he was anything but an ordinary army officer with a job at the War Office."

He strolled into the hall with the two men.

"I'll let you know what I hear from Cannes," he said. "And you have my number here and at the office. Because I've got a sort of hunch, boys, that the less we actually see of one another in the near future the better. And my final word—watch your step."

A slight drizzle was falling as Drummond and Standish reached the street, and they hailed a passing taxi.

"United Sports Club," said Drummond. "We may as well get down to this over a pint, Ronald." Standish lit a cigarette.

"A rum show," he remarked. "Damned rum. And the annoying part of it is that it's impossible to find out from Burton whether he had a good and perfectly genuine reason for crossing by that service. He may have had, and in that case the Chief's theory goes up in a cloud of steam. But if he didn't have—"

"In any event he'd manufacture one," Drummond cut in.

"If it wasn't true it might be possible to discover the fact. But the trouble is that it would immediately arouse all Burton's suspicions."

The taxi pulled up at the club, and they went inside. The smoking–room was practically empty, and drawing two easy chairs up to the fire they sat down.

"Let's pool resources, Hugh," said Standish. "What, if anything, do you know of Charles Burton?"

"I have seen him in all about six times," answered Drummond. "I accidentally trod on his foot at some ghastly cocktail party old Mary Wetherspoon threw at the Ritz, and we had a drink over the catastrophe. Save for that I don't think I've addressed three sentences to the man in my life. He seems a reasonable sort of individual though he ain't the type I'd choose to be shipwrecked on a desert island with."

"How did that remark about his not being English strike you?"

"It didn't—particularly. So far as I remember he speaks without the faintest trace of accent. In fact he must do, or the point would have occurred to me. But to be perfectly candid, Ronald, I do not feel that I know the man nearly well enough to form any opinion of him. He is the most casual of casual acquaintances."

"Have you ever been to his house in Park Lane?"

"Once—with some wench. Another cocktail party. I don't think I even spoke to him."

"But the flesh–pots of Egypt all right?"

"Very much so. Though the whole turnout rather gave one the impression that he had issued an ultimatum—'Let there be furniture; rich, rare furniture. Let there be pictures; rich, rare pictures.'"

"Precisely the criticism I heard," said Standish. "And it rather confirms what the Chief was saying about one day he was not—the next day he was."

"Yes," agreed Drummond doubtfully. "But I don't see that it takes us much further. I can think of three or four men who have suddenly made money, and promptly bought a large house with instructions to furnish regardless of cost."

"Do you know when he bought that house?"

"The time I went there was about a year ago, and so far as I know he'd been in it several months then."

"So presumably he took it when he first blossomed out in the City."

"Presumably."

"It would be interesting to know his history before then."

"That, I take it, he would say was nobody's business."

"D'you see what I'm getting at, Hugh? If by some lucky speculation he made a packet in the City before he burst on society, it is one thing. If on the contrary he just arrived out of the blue, it is another. In the first event Talbot's question as to where he got his money is answered; in the second it isn't."

"It should be easy to find out," said Drummond.

"It doesn't seem as if the Chief has been able to do so, and he can ferret out information from a closed oyster. Of course, he's had a very short time. But I can't help feeling that our first line is Mr. Charles Burton's past. Did he have a father who left him money? Did he make it himself, and if so where? Or…"

"Or what?" asked Drummond curiously.

"Has he been installed there for some purpose which at the moment is beyond us?

"And Jimmy was on the track."

"Exactly. I believe that is what was at the bottom of the Chief's mind. And if so the sorest man in England was our Charles when his name was taken going up in the boat–train."

Hugh Drummond lay back in his chair and lit a cigarette.

"First line settled," he remarked. "But it is the second that contains the snags, I'm thinking. I hardly know the blighter; you, I gather, don't know him at all. How do we set about attaching ourselves to his person with a view to extracting his maidenly secrets? Charlie is going to smell a rodent of that size pretty damn' quick."

"Sufficient unto the day, old boy. It'll have to be worked through mutual friends. By the way, has he got any other house besides the one in Park Lane?"

"Ask me another. Not that I know of, but that means nothing."

Drummond sat up suddenly.

"An idea, by Jove! Algy. Algy Longworth. He knows Burton fairly well. Waiter! Go and telephone to Mr. Longworth and tell him to come round to the club at once under pain of my severe displeasure.

"I remember now," he continued, as the waiter left the room. "Burton has got a house in the country somewhere. Algy went and stayed there last summer. Crowds of fairies; swimming–pool; peacocks in the grounds type of thing."

"However he got it the money is evidently there," said Standish dryly.

"Mr. Longworth is coming round at once, sir." The waiter paused by Drummond's chair.

"Good. Then repeat this dose and bring one for Mr. Longworth. A drivelling idiot is our Algy," he went on as the man moved away, "but there is a certain shrewdness concealed behind that eyeglass of his which may prove useful."

"At any rate he gives us a point of contact with Burton," said Standish. "And that's all to the good."

Ten minutes later Algy Longworth arrived and Drummond swung round his chair.

"Come here, you pop–eyed excrescence. What the devil are you all dressed up like that for? And you've dribbled on your white waistcoat. You look awful."

"Thank you, my sweet one. Evening, Ronald." The newcomer adjusted his eyeglass, and smiled benignly.

"Evening, Algy. Take a pew."

"You wish to confer with me—yes? To suck my brain on some deep point of international import? Gentlemen—if I may be permitted so to bastardise the word—I am at your service."

"Look here, Algy," said Drummond, "there may be a spot of bother in the air. Only may; we don't know yet. So this conversation is not to go beyond you. What do you know about Charles Burton?"

"Charles Burton!" Algy Longworth stared at him. "What's he been doing? Watering the Worcester sauce? As a matter of fact it's darned funny you should ask that, Hugh; I'm going to that place of his to–night. Hence the glad rags."

"What place? His house in Park Lane?"

"No; no. The Golden Boot."

"The new Club that's just opened? It's Burton behind it, is it?"

"Entirely. He found all the others so ghastly boring that he decided to have one run on his own lines. More than likely he'll be there himself. However, what is it you want to know about him?"

"Everything you can tell. What sort of a bloke is he?"

"He's all right. Throws a damned good party. Stinks of money. Clean about the house and all that kind of thing."

"D'you know where he got his money?"

"Haven't an earthly, old boy. Cornering lights for cats, or something of that sort, I suppose. Why?"

"Where is his house in the country?"

"West Sussex. Not far from Pulborough. I went and stayed there last July."

"I remember you telling me about it," said Drummond. "Algy, would you say he was English?"

Algy stared at him, his glass half–way to his mouth.

"I've never really thought about it," he said at length. "I've always assumed he was, especially with that name. He speaks the language perfectly, but for that matter he speaks about six others equally well. I'd put it this way—he isn't obviously not English."

"That I know," said Drummond.

"And I should think Sir George would have satisfied himself on that point," continued Algy. "You know old Castledon—the most crashing bore in Europe?"

"His wife is the woman with a face like a cablose, isn't she?"

"That's it. Well, Molly, their daughter, is an absolute fizzer. When you see the three of 'em together you feel that you require the mysteries of parenthood explained to you again. However, Burton met Molly at some catch–'em–alive–'o dance in Ascot week, and as our society writers would say, paid her marked attention. So marked that Lady Castledon who was attending the parade as Molly's chaperon had a fit in a corner of the room, and was finally carried out neighing. She already heard the Burton doubloons jingling in the Castledon coffers, which by all accounts sadly need 'em."

"What's the girl's reaction?" asked Drummond. "Definitely anti–click. After all, she's young; she's one of this year's brood of debs. But what I was getting at is, that though Sir George can clear a room quicker than an appeal for charity, he's a darned fine old boy. And he's not the sort of man who'd let his daughter marry merely for money, or get tied up with anyone he wasn't satisfied about."

Algy drained his glass.

"Look here, chaps," he said, "it seems to me I've done most of the turn up to date. Why this sudden interest in Charles Burton?"

"We've got your word you'll keep it to yourself, Algy?"

"Of course," was the quiet answer.

"Good. Then listen."

He did—in absolute silence—whilst they put him wise.

"Seems a bit flimsy," he remarked when they had finished. "Though I agree that it's not like Burton to cross via Newhaven."

"Of course it's flimsy," said Drummond. "There's not a shred of evidence to connect Burton with Jimmy's death. It's just a shot in the dark on the Chief's part. And if we find out nothing, no harm is done. On the other hand it is just possible we may discover that it was a bull's–eye."

"I must say that he's not a man I'd like to fall foul of," remarked Algy thoughtfully. "I don't think he'd show one much mercy. He sacked the first manager he put into the Golden Boot at a moment's notice for the most trivial offence. But murder is rather a tall order."

"My dear Algy," said Standish, "the tallness of the order is entirely dependent on the largeness of the stake. And if Jimmy was on to something really big…"

He shrugged his shoulders and lit a cigarette.

"Perhaps you're right," said Algy. "Well, boys, I'm afraid I haven't been of much assistance, but I really know very little about the fellow myself. Why don't you come round to the Golden Boot with me now?"

"Short coats all right?"

"Good Lord! yes. Though he insists on evening clothes. Of course, I can't guarantee that he'll be there, and even if he is I don't see that it will do any good. But you might stumble on something, and you're bound to find a lot of people there that you know."

"What about it, Ronald?" said Drummond. "It can't do any harm."

"It can't. But I don't think we'll both go, Hugh. If anything comes out of this show it would be well to have one completely unknown bloke on our side—unknown to Burton, I mean. Now he knows you and he knows Algy; he does not know me. So for the present, at any rate, we won't connect you and me. You toddle off with Algy; as he says, you might find out something. Let's meet here for lunch to–morrow, and I'll put out a few feelers in the City during the morning."

Drummond nodded.

"Sound idea. You've got a wench with you, I suppose, Algy?"

"I'm with a party. Why don't you join up too?"

"I'll see. It's one of these ordinary bottle places, I take it?"

"That's right. Same old stunt in rather better setting than usual—that's all. Night–night, Ronald."

II: The Golden Boot

As Algy Longworth had said, it was the same old stunt. After a slight financial formality at the door, Drummond became a guest of the management for the evening with all the privileges appertaining to such an honoured position. Though unable to order a whisky and soda, he was allowed—nay, expected—to order a bottle. To consume one drink was a crime comparable to murdering the Archbishop of Canterbury; to consume the entire bottle was a great and meritorious action.

Accustomed, however, as he was to these interesting sidelights on our legal system he gave the necessary order, and then glanced round the room. Being only just midnight there were still many empty tables, though he saw several faces he recognised. It was a long, narrow building, and a band, in a fantastic red and green uniform, was playing at the far end. But the whole get–up of the place was, as Algy had said, distinctly better than usual.

Algy's party had not yet arrived, so they sat down at an empty table, near the microscopic dancing–floor, and Drummond ordered a kipper.

"I'll wait, old boy," said Algy, and at that moment a girl paused by their table.

"Hullo! darling." He scrambled to his feet. "You look absolutely ravishing. Hugh, you old stiff—this is Alice. Around her rotates the whole place; she is our sun, our moon, our stars. Without her we wilt; we die. Hugh; Alice."

"You blithering imbecile," said the girl with a particularly charming smile. "Are you his keeper, Hugh?"

Drummond grinned—that slow, lazy grin of his, which made so many people wonder why they had ever thought him ugly.

"Lions I have shot, Alice; tigers, even field mice; but there is a limit to my powers. When this palsied worm joins his unfortunate fellow guests will you come and kipper with me?"

"I'd love to," she answered simply, and with a nod moved on.

"I'm glad you did that, Hugh," said Algy. "She's an absolute topper, that girl. Name of Blackton. Father was a soldier."

"What's she doing this job for?"

"He lost all his money in some speculation. But you'll really like her. There's no nonsense about her, and she dances like an angel." He lowered his voice. "No sign of C. B. so far."

"The night is yet young," said Drummond. "And even if he does come I'm not likely to get anything out of him. It's more the atmosphere of this place that I want, and sidelights from other people."

"Alice might help you there," remarked Algy. "She's been here since it opened. Hullo! here come my crowd. So long, old boy, and don't forget if anything does emerge the bunch are in on it."

He drifted away and a smile twitched round Drummond's lips. How many times in the past had not the bunch been in on things? And they were all ready again if and when the necessity arose.

If and when…The smile had gone, and he was conscious of a curious sensation. Suddenly the room seemed strangely unreal; the band, the women, the hum of conversation faded and died. In its place was a deserted cross–roads with the stench of death lying thick like a fetid pall. Against the darkening sky green pencil lines of light shot ceaselessly up, to turn into balls of fire as the flares lobbed softly into no–man's–land. In the distance the mutter of artillery; the sudden staccato burst of a machine–gun. And in the ditch close by, a motionless figure in khaki, with chalk white face and glazed staring eyes, that seemed to be mutely asking why its legs should be lying two yards away being gnawed by rats.

"A penny, Hugh."

With a start he glanced up; Alice was looking at him curiously.

"For the moment I thought of other things," he said quietly. "I was back across the water, Alice; back in the days of the madness. I almost seemed to be there in reality—it was so vivid. Funny, isn't it, the tricks one's mind plays?"

"You seemed to me, Hugh, to be staring into the future—not into the past." She sat down opposite him. "The world was on your shoulders and you found it heavy. This is the first time you've been here, isn't it?" she continued lightly.

"The future." He stared at her gravely. "I wonder. However, a truce to this serious mood. Yes, it is the first time I've been here; I've been up in Scotland since it opened. And as such places go it seems good to me. I gather that one Charles Burton is behind it?"

"Do you know the gentleman?" Her tone was non–committal, but he glanced at her quickly.

"Very slightly," he said. "You do, of course."

"Yes, I know him. He is in here most nights when he's in London."

"Do you like him?"

"My dear Hugh, girls in my position neither like nor dislike the great man. We exist by virtue of his tolerance."

Drummond studied her in silence.

"Now what precisely do you mean?" he enquired at length.

"Exactly what I say. Caesar holds the power of life or death. There is no appeal. If he says to me, 'Go'—I go. And lose my job. Which reminds me that you'll have to stand me a bottle of champagne for the good of the house. Sorry about it, but there you are."

Drummond beckoned to a waiter and glanced at the wine list.

"Number 35. Now tell me, Alice," he said when the man had gone, "do you like this job?"

"Beggars can't be choosers, can they? And since secretaries are a drug on the market what is a poor girl to do?"

"Does he expect you to—?"

"Sleep with him?" She gave a short laugh. "So far, Hugh, I have not been honoured."

"And if you are?"

"I can think of nothing I should detest more. I hate the swine."

"Steady, my dear." For a moment he laid his hand on hers. "The' swine' has just arrived. And I don't think you'll be honoured this evening at any rate."

A sudden silence had fallen on the Golden Boot. Head waiters, waiters, under waiters were prostrating themselves at the door. And assuredly the woman who had entered with Charles Burton was sufficient cause. Tall, with a perfect figure, she stood for a moment regarding the room with an arrogance so superb, that its insolence was almost staggering. Her shimmering black velvet frock was skin–tight; she wore no jewels save one rope of magnificent pearls. Her eyes were blue and heavy lidded; her mouth a scarlet streak. And on one finger there glittered a priceless ruby.

As if unconscious of the effect she had created she swept across the room behind the obsequious manager, whilst Charles Burton followed in leisurely fashion, stopping at different tables to speak to friends. At length he reached Drummond's and the eyes of the two men met.

"Surely…" began Burton doubtfully.

"We met at a cocktail party, Mr. Burton," said Drummond with a smile. "I trod on your foot and nearly broke it. Drummond is my name."

"Of course, I remember perfectly. Ah! good evening, Miss Blackton." He gave the girl a perfunctory bow; then turned back to Drummond. "I don't think I've seen you here before."

"For the very good reason that it is the first time I've been. I've only just got back from the north."

"Shooting?"

"Yes. I was stalking in Sutherland."

"Well, now that you've been here once I hope you'll come again. It's my toy, you know."

With a nod he moved on, and Drummond watched him as he joined the woman. Then he became aware that a waiter was standing by him with a note.

"From the gentleman with the eyeglass, sir."

He opened it, and saw a few words scrawled in pencil.

"Charlie B. He make whoopee. But what about poor Molly C."

Drummond smiled and put the note in his pocket.

"From the idiot boy," he said. "Commenting on Mr. Burton's girl friend."

"She's an extraordinarily striking woman," said Alice Blackton. "I wonder if he picked her up at Nice."

Drummond stared at her.

"Did you say Nice?"

"I did. He's just come back from the Riviera, you know."

"Has he indeed? That is rather interesting." She raised her eyebrows.

"I'm glad you find it so. I'm afraid that Mr. Burton's comings and goings leave me stone cold."

"Tell me, Alice, why do you hate him?"

"Hate is perhaps too strong a word," she said. "And yet I don't know. I think it's because I don't trust him a yard. I don't mean only over women, though that comes into it too. I wouldn't trust him over anything. He's completely and utterly unscrupulous."

"Are you speaking from definite knowledge, or is that merely your private opinion?"

"If by definite knowledge you mean do I know that he's ever robbed a church—then no. But you've only got to meet him in a subordinate capacity like I have, to get him taped."

She looked at Drummond curiously.

"You seem very interested in him, Hugh."

"I am," said Drummond frankly. "Though the last thing I want is that he should know it."

"You can be sure that I won't pass it on. Why are you so interested, or is it a secret?"

"I'm afraid it is, my dear. All I can tell you is that I'm very anxious to find out everything that I can about the gentleman. And though I can't say why, your little piece of information about his having been on the Riviera recently, is of the greatest value. Do you know how long he was there for?"

"I can tell you when he left England. It was exactly a fortnight ago, because he was in here the night before he flew over."

"I gather he always flies," said Drummond.

"He's got his own machine," remarked the girl. "And his own pilot."

"Did he go over in it this time?"

"I suppose so. He always does."

"Curiouser and curiouser," said Drummond. "I know," he went on with a smile, "that this must seem very mysterious to you. Really, it isn't a bit. But at the moment I just can't tell you what it is all about. Your father was a soldier, wasn't he?"

"He was. Though how did you know?"

"Algy told me. Now I can let you in to this much. It is the army that is interested in Mr. Burton. I tell you that, because I'm going to ask you to do something for me."

"What?" said the girl.

"Keep an eye on him—that's all, and let me know anything about his movements that you can find out, however seemingly trivial."

"My dear man, I can't do much, I'm afraid."

"You never know," said Drummond quietly. "As I've already told you, that piece of information about Nice is most valuable. Another thing. Not only his movements, but also the people he brings here. Now would it be possible to discover the name of that woman?"

"Presumably he's signed her in, but whether under her real name or not is another matter. I can find out if you like."

"Do—like an angel."

"All right. I'll go and powder my nose."

A good wench, reflected Drummond as he watched her threading her way through the tables. Definitely an asset. And though probably ninety per cent of what she could pass on would be valueless, the remaining ten might not. Witness the matter of Nice. True that would certainly have come out in the course of time—Burton's visit there was clearly no secret. At the same time it was useful to have it presented free of charge, so to speak. But the really important thing was the installation in one of the enemy's camps of a reliable friend.

"O.K., baby?"

Algy had strolled over to his table.

"Very much so, old boy. A damned nice girl."

"That's a bit of mother's ruin our Charlie has got with him."

"Alice is just trying to find out who she is. Algy—Burton was at Nice, while Jimmy was at Cannes." Algy whistled.

"The devil he was. Have you told Alice anything about it?"

"No. Safer not to at present. She doesn't like him, Algy."

"None of the staff do, old lad. Alice—my life, my all—this revolting man hasn't been making love to you, has he?"

"Not so that you'd notice, Algy," laughed the girl, sitting down. "She is a Madame Tomesco, Hugh."

"It has a Roumanian flavour," said Drummond.

"And mark you, boys and girls, I could do with a bit of Roumanian flavouring myself," declared Algy. "I could do that woman a kindness; yes, I could. Well, au revoir, my sweets. If he plucks at his collar, Alice, its either passion or indigestion, or possibly both. You have been warned."

"Quite, quite mad," said the girl. "But rather a dear. You must give me your address, Hugh, before you go, so that I can send along the doings."

He scribbled it down on a piece of paper and his telephone number.

"Be careful, my dear," he said gravely. "I have a feeling that if the gentleman got an inkling that you were spying on him he would not be amused. I'll go further. If there is anything in what we suspect you'd be in grave danger."

Her eyes opened wide.

"How perfectly thrilling! Promise you'll tell me sometime what it's all about?"

"Thumbs crossed. Waiter, let me have my bill. I've put my name on the whisky; keep it for me for next time."

"Come again soon, Hugh," said the girl.

"I sure will. Good night, dear. I really am infernally sleepy."

The rain had ceased when he got outside, and refusing a taxi he started to walk to his flat. Though the Golden Boot was much better ventilated than the average night club, it was a relief to breathe fresh air again. The streets were wet and glistening in the glare of the arc lights; the pavements almost deserted. Every now and then some wretched woman appeared from seemingly nowhere, and it was while he was fumbling in his pocket for some money for one of them that his uncanny sixth sense began to assert itself.

"Bless you! You're a toff," said the girl, but Drummond hardly heard her. He was staring back the way he had come. What was that man doing loitering about, some fifty yards away?

He walked on two or three hundred yards; then on the pretext of doing up his shoe he stopped. The man was still there; he was being followed. With a puzzled frown he strode on; how in the name of all that was marvellous could he have incurred anybody's suspicions?

He decided to make sure, and to do so he employed the old ruse. He swung round the corner from Piccadilly into Bond Street; then he stopped dead in his tracks. And ten seconds later the man shot round too, only to halt, in his turn, as he saw Drummond.

"Good evening," said Drummond affably. "You are not, if I may say so, very expert at your game. Possibly you haven't had much practice."

"I don't know what you're talking about," muttered the other, and Drummond studied him curiously. He looked about thirty, and was decently dressed. His voice was refined; he might have been a bank clerk.

"Why are you following me?" he asked quietly.

"I don't know what you mean. I'm not following you."

"Then why did you stop dead when you came round the corner and saw me? I fear that your powers of lying are about equivalent to your powers of tracking. Once again I wish to know why you are following me."

"I refuse to say," said the man.

"At any rate we advance," said Drummond. "You no longer deny the soft impeachment. But as it's confoundedly draughty here I suggest that we should stroll on together, chatting on this and that. And in case the point has escaped your notice, I will just remind you that I am a very much larger and more powerful man than you. And should the ghastly necessity of hitting you arise, it will probably be at least a week before you again take your morning Bengers."

"You dare to lay a hand on me," blustered the man, "and I'll…"

"Yes," said Drummond politely. "You'll what? Call the police? Come on, little man; I would hold converse with you."

With a grip of iron he took the man's right arm above the elbow, and turning back into Piccadilly he walked him along.

"Who is employing you?"

"I refuse to say. God! you'll break my arm."

"Quite possibly."

And at that moment a policeman came round Dover Street just in front of them.

"Officer," cried the man. "Help!"

For a moment Drummond's grip relaxed, and like a rabbit going down a bolt–hole the man was across the road and racing down St. James's Street.

"What's all this, sir?" said the constable as Drummond began to laugh.

"A gentleman who has been following me, officer," he said. "I'm afraid I was rather hurting him."

"Oh! I see, sir."

The constable looked at him significantly and winked. Then with a cheery "Good night, sir," he resumed his beat.

But the smile soon faded from Drummond's face, and it was with a very grave expression that he walked on. He had only got down from Scotland that day, so under what conceivable circumstances could he be being followed? That it was added confirmation that the Chief was right was indubitable; it could not be anything else than the Jimmy Latimer affair. There was a literally nothing else that it could be. But how had they got on to him—Drummond? That was what completely defeated him. For one brief moment the possibility of Alice Blackton being a wrong 'un crossed his mind; then he dismissed it as absurd. What could be her object? She had his address; she knew his name, so what purpose would it serve to have him followed home? But if it was not her who could it be?