Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: e-artnow

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

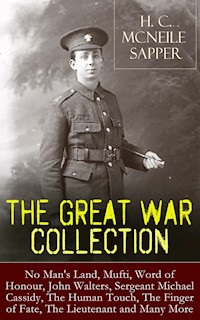

This carefully crafted ebook: "H. C. McNeile - The Great War Collection: No Man's Land, Mufti, Word of Honour, John Walters, Sergeant Michael Cassidy, The Human Touch, The Finger of Fate, The Lieutenant and Many More" is formatted for your eReader with a functional and detailed table of contents. Herman Cyril McNeile (1888-1937) commonly known as H. C. McNeile or Sapper, was a British soldier and author. Drawing on his experiences in the trenches during the First World War, he started writing short stories and getting them published in the Daily Mail. McNeile's stories are either directly about the war, or contain people whose lives have been shaped by it. His war stories were considered by contemporary audiences as anti-sentimental, realistic depictions of the trenches, and as a "celebration of the qualities of the Old Contemptibles". "No one who has ever given the matter a moment's thought would deny, I suppose, that a regiment without discipline is like a ship without a rudder. True as that fact has always been, it is doubly so now, when men are exposed to mental and physical shocks such as have never before been thought of. The condition of a man's brain after he has sat in a trench and suffered an intensive bombardment for two or three hours can only be described by one word, and that is—numbed. The man becomes half-stunned, dazed; his limbs twitch convulsively and involuntarily; he mutters foolishly—he becomes incoherent. Starting with fright he passes through that stage, passes beyond it into a condition bordering on coma; and when a man is in that condition he is not responsible for his actions. His brain has ceased to work..." - H. C. McNeile, Men, Women and Guns Table of Contents: When Carruthers Laughed Mufti John Walters Men, Women and Guns No Man's Land The Human Touch Word of Honour The Man in Ratcatcher The Lieutenant and Others Sergeant Michael Cassidy, R.E. Jim Brent

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 3098

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

H. C. McNeile - The Great War Collection: No Man's Land, Mufti, Word of Honour, John Walters, Sergeant Michael Cassidy, The Human Touch, The Finger of Fate, The Lieutenant and Many More

Table of Contents

When Carruthers Laughed

I. — WHEN CARRUTHERS LAUGHED

HENRY ST. JOHN CARRUTHERS was something of an enigma. Where he lived I have no idea, except that it was somewhere north of Oxford Street. But we were both members of the Junior Strand, which, as all the world knows, is not a club frequented largely by the clergy or the more respectable lights of the legal profession. It is a pot-house frank and unashamed, but withal a thoroughly amusing one.

It is not a large club, and the general atmosphere in the smoking-room is one of conviviality. Honesty compels me to admit that the majority of the members would not find favour in the eyes of a confirmed temperance fanatic, but since the reverse is even truer the point is not of great interest. Anyway, it was there that I first met Henry St. John Carruthers.

He was, I should imagine, about thirty-six years of age—neither good-looking nor ugly. Not that a man's looks matter, but I mention it en passant. He was sitting next to me after lunch, and we drifted into conversation about something or other. I didn't even know his name. I have entirely forgotten what we talked about. But what I do remember, as having impressed me during our talk, is his eyes. Not their size or colour, but their expression.

I sat on for a few minutes after he had gone trying to interpret that expression. It wasn't exactly bored: it certainly wasn't conceited—and yet it contained both those characteristics. A sort of contemptuous resignation most nearly expresses it: the look of a man who is saying to himself—'Merciful heavens! what am I doing in this galaxy?'

And yet, I repeat, there was very little conceit about it: it was too impersonal to be in the slightest degree offensive.

"Rum fellow that," said the man sitting on the other side of me, after he had gone. "You never seem to get any further with him."

It was then I learnt his name and the fact that he was in business in the City. "A square peg in a round hole if ever there was one," went on my informant. "From the little I know of him he'd be happier in the French Foreign Legion than sitting with his knees under a desk."

Time went on and I saw a good deal of Henry St. John Carruthers. And as my acquaintance with him grew—not into anything that may be called friendship but into a certain degree of intimacy—I realised that my casual informant was right. That City desk was a round hole with a vengeance. And the fact supplied the clue to the expression in his eyes. It was the life he lived that it was directed against—and himself for living that life.

Not that he ever complained in so many words: he was not a man who ever asked for sympathy. It was his bed and he was going to lie on it; he asked no one else to share it with him. Very much alone did he strike me as being: a man who would go his own way and thank you to go yours. It would be idle to pretend that he was popular. And in view of his manner it was not surprising. His somewhat marked air of aloofness tended to put a damper on the spirits of men he found himself with.

"Hang it all!" said Bearsted, a stockbroker, one night as the door closed behind Carruthers. "Has anyone ever seen that fellow laugh?"

I thought over that remark during the next few days, and finally came to the surprising conclusion that it was true. I'd never considered the matter before, and now that it had been brought to my notice it struck me that I never had seen Henry St. John Carruthers laugh. I'd seen him smile, I'd seen a twinkle in his eye—but an outright laugh, never. So one evening I tackled him about it.

"Do you know, Carruthers," I said, "that in the course of the year since I first met you I've never seen you laugh?"

He stared at me for a moment; then he scratched his head.

"Haven't you?" he answered. "Don't I laugh? I wasn't aware of the fact. Though, incidentally, what there is to laugh at in life I don't know. Personally, I think it's too darned boring for words."

"Oh, come!" I said, "that's a bit scathing, isn't it? Everything has its funny side. Go and look steadily into the face of the Honourable James over there in the corner. That ought to do the trick."

"Thanks," he answered shortly, "I'd sooner keep the record unbroken. Besides, he wouldn't make me laugh: he'd make me cry. I suppose," he went on thoughtfully, "that there are uses for things like that in the world."

"Certainly," I answered. "The old man has some excellent shootings."

"Well, I wish to heaven you'd bag the son the next time you go there. Good Lord, he's coming over here!"

I glanced round: the Honourable James had risen and was bearing down on us.

"I say, dear old boy," he burbled, coming to rest in front of me, "my old governor wants me to bring down two guys next Saturday. Would you care to come?"

"Very much, James," I said.

"What about you, Carruthers?" went on James.

"Thanks, no," grunted the other. "I'm afraid I'm already engaged."

The Honourable James continued to burble, and after about two minutes Carruthers, with a strangled snort, got up and left.

"By Jove!" said James plaintively, "he never waited to hear the end of the story. You know, Bill,"—he waxed confidential—"I don't believe that fellow likes me."

"My dear James," I cried, "what put that idea into your head? I expect he's got an appointment."

"Yes—but he might have waited to hear the end of the story," repeated James. "No—I don't think he likes me. He never even laughed."

He drifted away—the personification of utter futility— leaving me shaking silently. I had been privileged to gaze on Carruthers's face as he left the room.

"It would take more than you, James, to make him laugh," I called after him. "In fact, if you ever do I'll stand you a drink."

A promise which I repeated to Carruthers when, half an hour later, he returned warily to the room.

"It's all right," I reassured him. "Our little James has gone. I gathered that he has a date with the most beautiful woman in London."

"Long may she keep him occupied," he grunted. "He is the most ghastly example of a Philandering Percy I've ever seen. Still, I suppose when a fellow has got the amount of money he possesses, beautiful women will suffer in silence."

And an hour later we rose to go home. The night was fine and warm, and refusing a waiting taxi we fell into step and walked. And Carruthers, I remember, was still inveighing against the system by which the Honourable Jameses of this world inherit totally undeserved wealth.

"Put that excrescence on his own feet," he argued, "and what would be the result? Take away his money and let him fight for his food, and where would he be?"

"Still," I murmured, "a man is the son of his father."

"Call that thing a man," he grunted. "Look here, I want a drink."

We were at the corner of Albemarle Street, and I glanced at my watch.

"It's half-past eleven," I remarked. "In a moment of mental aberration I joined the Sixty-Six a few weeks ago. Let's go there."

Now, the Sixty-Six, as all the world knows, is one of those night-clubs that spring up like mushrooms in a damp field, endure for a space, and then disappear into oblivion to the tune of a hundred-pound fine. The fact that they open a few weeks later as the Seventy-Seven, and the same performance is repeated, is neither here nor there.

"Right," said Henry St. John Carruthers. "One can only hope the police will not choose tonight to raid it!"

And at that moment he paused in the door and blasphemed. I glanced over his shoulder, and then, taking him gently by the arm, I propelled him across the room to a vacant table.

"If we get the police as well," I murmured, "our evening will not be wasted."

In the centre of the floor was the Honourable James. He hailed us with delight as we passed, and Carruthers sat down muttering horribly. "Can I never get away from that mess?" he demanded hopelessly. "I ask you—I ask you—look at him now!"

And assuredly the Honourable James was a pretty grim spectacle. I lay no claim to being a dancing man myself, but James attempting to Charleston was a sight on which no man might look unmoved. In fact, the only thing about the Honourable James which caused one any pleasure was his partner. To say that she was attractive would be simply banal: she was one of the most adorable creatures I have ever seen in my life. Moreover, she seemed to reciprocate James's obvious devotion. Three times did I see her return his fish—like glance of love with a slight drooping of her eyelids which spoke volumes.

"Evidently out to hook him," I remarked, turning to Carruthers. "Hullo! what has stung you?"

For he was leaning forward, staring at the girl with a completely new expression in his eyes.

"Good Lord!" he muttered, half to himself. "It can't be. And yet—"

He suddenly stood up and glanced round the room; then, equally abruptly, he sat down again. "It is." he remarked. "As I live—it is. How deuced funny!" And he grinned: he positively grinned.

"What is?" I demanded. "Elucidate."

"They will part him from his money," he went on happily. "And I hope they sock him good and strong."

"What the devil are you talking about?" I said peevishly.

"If you look over there to the right," he answered, "behind that woman in green, you will see a large and somewhat bull-necked man sitting at a table by himself. He is smoking a cigar, and gives one the impression that he owns the earth."

"I've got him," I said.

"Just a year ago," he continued, "I was over in Chicago. I was sitting in the lounge of my hotel talking to an American I knew who was something pretty big in the police. He'd been giving me a good deal of inside information about crime over there, when suddenly he leant forward and touched me on the arm. 'See that guy who has just come in,' he said, 'with a cigar sticking out of his face?'

"I saw him all right; you couldn't have helped it if you tried. 'Well, that bloke,' went on my pal, 'is just about the highest spot in the confidence game that we've got. He specialises in you Britishers, and I reckon he's parted more of you from your money than one is ever likely to be told about.'

"'What's his line?' I demanded.

"'Anything and everything,' he replied. 'From running bogus charities to blackmail. And he generally works with an amazingly pretty girl. There she is: just joined him.'

"'His wife?' I said. My pal shrugged his shoulders. 'I shouldn't imagine the Church has been over-worked in the matter,' he answered. 'But you can call her that.'"

Henry St. John Carruthers lay back in his chair and actually chuckled.

"You mean?" I said slowly.

"Precisely," he answered. "There they are. And so is dear James."

I glanced over at the table where the big man had been joined by James and the girl. He was smiling in the most friendly way and filling James's glass with more champagne. Then he handed him his cigar case, and James, coming out of a dream, helped himself. Then James relapsed into his dream to the extent of forgetting to light it. And the dream was what one would have expected in the circumstances.

Assuredly she was the most divinely pretty girl. And James was totally unable to take his eyes off her face. He was in the condition of trying to touch her hand under the table, of little by little moving his chair nearer hers, in the fond belief that the manoeuvre would pass unnoticed.

"Look here," I said, "we must do something."

"Why?" said Henry St. John Carruthers.

"Well, if what you say is right, they're going to blackmail that poor boob."

"And serve him darned well right," he answered shortly. "A man has got to buy his experience, and why should that horror be an exception?"

"That's going too far," I said, a little angrily. "You may not like him, but you can't let him be swindled by a couple of crooks."

He shrugged his shoulders indifferently. "I disagree entirely," he answered. "However, for the sake of argument, let's assume you're right. What do you suggest we should do?"

"Get James on one side and warn him," I said promptly.

"Try it," he remarked. "And then see the result. Do you really imagine, my dear chap, that you stand a dog's chance against that girl? The only result will be that you'll lose some good shooting."

"I don't care," I said doggedly. "Chance or no chance, I'm going to have a shot." I rose and crossed the room, leaving Carruthers smiling faintly.

"Excuse me, James," I said, bowing to the girl, "was it this week-end or next that you asked me to shoot?"

James had risen, and with my hand on his arm I drew him a little way from the table. "This coming one as ever is, old lad," he burbled. "I say, I want to introduce you to—"

"Look here, James," I interrupted urgently, "pay attention to what I'm saying." I was speaking in a low voice in his ear, and over his shoulder I saw the big man staring at me steadily. "These two people you're out with tonight are crooks."

"Crooks," bleated James. "Crooks?"

"For God's sake don't shout," I muttered. "Yes—crooks."

"Go to blazes!" said James succinctly. "And stay there. I'm going to marry this lady. What the dickens do you mean by crooks?"

He turned abruptly and sat down, leaving me standing there feeling a fool. And the feeling was not diminished by the look in the big man's eyes. I realised that he knew what I had come about; short of being deaf, he must have heard what James said. And his expression seconded James's remark as to my immediate destination.

"Well," said Henry St. John Carruthers, as I rejoined him. "What luck?"

"The silly fool can stew in his own juice," I answered shortly. "He says he's going to marry the girl."

"Quite possibly he may be," he remarked. "He's got enough money to make it worth her while. Well, I'm going to have another whisky-and-soda, and then I'm for bed."

"I still don't feel quite happy about it," I said. "After all, the old man is a very decent sort."

"Oh, dry up!" said Carruthers wearily. "You've done what you could, and you've got your answer. What the deuce is the good of worrying over a disease like that youth?" He finished his drink and rose. "I'm for the sheets. Coming?"

I followed him across the room, and we went into the cloakroom to get our hats.

James and his friends were still at their table, but though we passed close to them he took no notice of us. Which, when all was said and done, was hardly to be wondered at. I took my top-hat and put it on. As Carruthers said, he'd have to buy his experience.

And even as I was dismissing the matter from my mind the swing doors opened and the big man came in. His hands were in his pockets; the cigar still stuck out from his face. And he stood there in absolute silence, staring first at me and then at Carruthers. But principally at Carruthers.

It was an offensive stare, and I felt my pulse quicken a little. It was the stare that precedes a row: the stare that is designed to produce a row. And after a while—funnily enough, it seemed quite natural at the time—I faded out of the picture. Though it was I who had spoken to James, the issue narrowed down to the big man and Henry St. John Carruthers.

I think it was then that I realised for the first time that Carruthers was also a big man.

The depth of his chest was astonishing—and the broadness of his back. And with a queer little thrill I saw that his fists—big fists they were—were clenched at his sides. Moreover, for quite five seconds he had made no movement to take his opera hat, which was standing open on the counter beside him. He just stood staring at the big man, while the big man stared back at him. And neither the attendant nor I existed for either of them.

Then suddenly the music started, and with it the tension snapped. Like two dogs who have been eyeing one another and then at last move away, so did the big man pass back into the ballroom, while Carruthers turned round for his hat. And as he turned the swing door hit him in the side. Now, it was, I verily believe, accidental; the big man had passed through normally, and Carruthers being where he was, the door in swinging back had hit him.

But accident or no accident, the result was the same. Into Henry St. John Carruthers's eyes there came a look which spelt one word. And that word was murder.

That he was angry was not surprising. If there is one thing in this world which drives me to thoughts of battle, murder and sudden death, it is when a man lets a door swing in my face. But Carruthers was more than angry; he was white with rage. There was a pulse hammering in his throat, and for an appreciable time he stood there drumming with his fingers on the wall. Then he turned to me.

"The egregious James is lucky," he said quietly. "He shall not be parted from his money after all."

"You're not going to have a row in the club?" I said apprehensively. "It was an accident, I'm sure."

"An accident that I like not the savour of," he remarked in the same quiet voice. "But don't be alarmed; the sacred floor of the Sixty-Six shall not be desecrated."

"What do you propose to do?" I said, staring at him.

"If you care to wait and see, I shall be delighted to have your company," he answered. "If not, I'll say good night."

For a moment or two I hesitated; then, moved by a sudden impulse, I said: "I'll stand by to bail you out."

"Don't worry," he grunted. "If there's any bailing to be done, it won't be me."

He turned and left the room, and it was left to the attendant to sum up the situation. "Good night, sir," he said to me. "I reckon somebody is going to be 'urt."

So did I; and as I followed Carruthers up the stairs I had an attack of common sense. "Look here, old man," I remarked as I joined him in the street, "don't you think this jest has gone far enough? What's wrong with that bed you were talking about?"

It was then that Henry St. John Carruthers grew polite— astoundingly polite. And when a man grows polite at the same time that his nostrils are narrowed, the time for words is past. His hat was tilted back on his head: his hands were in his trouser pockets, and as he stood on the kerb he swayed a little on his heels. "I have already suggested that we should say good night," he said very distinctly—and held out his hand.

"Rot," I answered. "Where you go I go."

"Then shall we save our breath?" he remarked.

I shrugged my shoulders: the thing had got beyond me. And for a space of about ten minutes we smoked in silence. An occasional taxi went past in Piccadilly, and once a policeman strolled close by us along the pavement.

"Good night, officer," said Carruthers.

"Good night, gentlemen," he answered. "Looking for a taxi?"

"Shortly," said Carruthers, and the policeman walked on.

"He little knows," I murmured jocularly, "the desperadoes he has just encountered." And then, as he made no answer, I looked at him curiously. "What exactly are you going to do?" I said.

He held up his hand to a passing taxi. "Get in," he said curtly. "I want you to wait," he remarked to the man. "My friend and I will sit inside." He got in after me. "Do?" he said. "I'm going to break up that man."

And for a further space of ten minutes we smoked in silence, while I asked myself whether or not I was mad. To sit still solemnly waiting in a taxi, with the avowed intention of aiding and abetting, and quite possibly participating in, a street row was certainly a sufficient reason to induce the query. And yet a sort of excited curiosity kept me there. Mad or not, I intended to see the thing through.

"Sit back." Carruthers's voice cut in on my thoughts. "Here they come." I glanced through the window. Sure enough, there were the girl and James standing on the pavement. And a moment later the big man joined them. The commissionaire was calling up another taxi, and the instant they were in Carruthers leant out of the window. "Follow that car," he said. "And keep a good fifty yards behind."

"Right, sir," grinned the man, and we started.

Now, I have since wondered what Carruthers would have done had they lived at the top of a block of service flats. He'd have got at his quarry somehow, I'm convinced, but it might have seriously complicated matters. As it was, that side of the affair proved easy. Up St. John's Wood Road and past Swiss Cottage the chase lay, and we soon realised that our destination was one of those large and ultra-respectable houses in Hampstead. "Go past him when he pulls up," said Carruthers to the driver. "I'll tell you when to stop."

It was a detached house, standing back from the road, that their taxi halted in front of, and Carruthers stole a look at it as we went by. "Excellent," he muttered. "There's quite a bit of vegetation in the garden. And we'll have to reconnoitre the land first." He rapped on the window of the car, and we got out. "Keep in the shadow," he whispered, "and if you see a policeman say good night in an affable voice."

"Lord help me!" I groaned. "Lead on. I leave it to you."

We strolled back towards the house, when suddenly, to my horror, Carruthers started to sing. And at the same time I felt his hand grip my arm, and force me past the gate.

Just inside was standing a weasel-faced man, who stared at me as we went by. "The plot thickens," said Carruthers when we were out of earshot. "He will be your share."

"You're too generous," I remarked.

He swung me round again, and once more we walked past the house. Weasel-face was no longer there, but a light was shining from one of the ground-floor windows through a chink in the curtains.

"Now's our chance," he whispered. "Keep under cover of the bushes and don't make a sound."

The next instant he was through the gate, and I found time even then to marvel at the quickness of his movements—and the silence. He skirted round the edge of the lawn, while I followed him as rapidly as I could. By this time I was as excited as he was; considerably more so, in fact. Certainly he seemed as cool as a cucumber when I joined him underneath the window. "It's pretty grim," he breathed in my ear, "but I don't think it will last long. Listen."

And grim was not the word. At odd periods in my life I had heard the Honourable James in varying stages of fatuous imbecility. I had heard him in his cups. I had heard him endeavouring to tell humorous stories; but I had never heard him making love. And I sincerely trust I never shall again.

Gradually I wormed my way up till I could see into the room. Her arms were round his neck, and she was gazing into his eyes with a look of rapt adoration on her face. In fact, I was just beginning to feel thoroughly embarrassed—even an object like James might reasonably object to being watched in such a situation—when I heard a whisper in my ear: "Watch the door!"

It was slowly opening. Now, James had his back to it; the girl had not. And as it opened she kissed James firmly. James returned the compliment. And Carruthers chuckled.

"May heaven deliver us," he muttered, "but this came out of the Ark with Noah. Still, I suppose it's good enough for him."

Weasel-face was standing in the doorway—the picture of outraged horror. The girl had risen to her feet with a pitiful cry of terror, while James, plucking at his collar, was helping the situation by remarking: "I say, by Jove! what's this fellah want?"

"My husband!" gasped the girl.

"You hound!" hissed Weasel-face.

"Oh! but I say—dash it all!" spluttered the Honourable James.

And then Carruthers pushed up the window and vaulted into the room. "Good evening," he remarked affably. "Shall we cut out the rest?"

Weasel-face and the girl seemed bereft of speech; they just stood there staring at him blankly. In fact, only James seemed capable of utterance, and that was when he saw me. "Hullo, old lad!" he burbled. "What brings you here?"

"So it's you, is it?" came a harsh voice from the door. The big man was standing there chewing a cigar, and he came slowly towards Carruthers, staring at him through narrowed eyes. And once again I had a feeling of being out of the picture. The thing had narrowed down to the two of them. "May I ask what you're doing in my house?" said the big man.

"Waiting to give you a lesson in manners." answered Carruthers.

"Is that so?" said the big man softly, and a fist like a leg of mutton whizzed past Carruthers's ear. A believer in deeds, not words, evidently, but it is inadvisable to start scrapping with a cigar in your mouth. That cigar disintegrated suddenly, and the big man stepped back with a grunt as Carruthers caught him fairly on the mouth.

And then in perfect silence they got down to it. I was watching Weasel-face, but he made no attempt to interfere. A gentleman of discretion, he very wisely decided that the matter had passed beyond him. And no bad judge either, when two heavyweights are fighting for a knock-out in a room full of furniture.

Moreover, the big man could use his fists; there was no doubt about that. That first jolt on the face had roused the devil in him, and some of his blows, delivered with a grunt of rage, would have finished the thing then and there if they'd got home. But they didn't, and gradually his breathing began to grow stertorous, and he started to slog wildly.

It was a smash on the point of the jaw with the whole weight of the body behind it that ended it. It took the big man clean off his feet and landed him crumpled up in a corner, where he lay staring at his opponent with murder in his eyes.

"Had enough?" said Henry St. John Carruthers.

"I'll kill you for this," said the big man, but he made no movement to rise.

"Some other time I shall be at your service." remarked Carruthers politely. "Just now I think we will leave you. Come on, you fellows. I know of a haunt where a man may obtain beer."

We left as we had come—through the window, with the Honourable James clinging to us even closer than a brother.

"But I say, dear old chaps," he burbled for the twentieth time as we got into a belated taxi, "what's it all mean—what?"

"Dry up," said Carruthers morosely. "Things like you ought to have a nurse."

"But she never told me she was married," pursued James.

"May Allah deliver me!" Carruthers contemplated him dispassionately. "She surely told you, didn't she, that her father had a living in Gloucestershire?"

"Yorkshire, she said," remarked James.

"And that one brother was up at Oxford? I thought so. He used always to be in the Guards during the War."

"By Jove! then—you knew her," said James. "What an extraordinary coincidence!"

"I shall weep in a minute," said Carruthers pessimistically.

"Don't do that, old man," I answered. "Once or twice tonight I thought you were going to break your record. You got as far as grinning, anyhow. Can't you raise a laugh, even out of James?"

"Laugh," he groaned. "Laugh! Come on—here we are. Let's get down to that beer. Perhaps if I look at him quietly for half an hour I might."

We went upstairs, and I left them to go and wash my hands. And all of a sudden I became aware of a strange noise. It was a discordant sound, rising and falling at, intervals, and somewhat reminiscent of the female hyena calling to her mate. I suppose it must have been going on for about half a minute when the door burst open and the Honourable James rushed in.

"I say, dear old boy," he cried anxiously, "is that bloke Carruthers quite right in his head, and all that?"

"What's the matter?" I asked.

"Well, it was quite accidental, don't you know—what— but I never realised he was standing in the jolly old doorway. Just behind me, don't you know. And I went and unloosed the door, which caught him a frightful biff in the chest. I mean, I thought he'd be deuced annoyed and all that—but listen to him. Have you ever heard such a row? Do you see anything to laugh at?"

II. — THE SNAKE FARM

SANTOS was at its worst. The heat, like a stagnant pall, hung over the harbour: the few passengers who had not gone up to San Paolo lay about on deck and mopped their foreheads. And I was on the verge of dropping off to sleep when I saw them coming up the gangway.

They were new passengers and I studied them idly. The woman— she was little more than a girl—was of the fluffy type: pretty in a rather chocolate-box way, with fair hair and a charming figure. The sort that one expects to be the life and soul of the ship, dancing every dance, and, in the intervals, throwing quoits into receptacles ill-designed to receive them. And it came therefore as almost a shock when she stood close to my chair waiting for the man and I could see her face distinctly.

The expression lifeless is hackneyed, and yet I can think of no other word to describe adequately how her appearance struck me. She was wearing a wedding-ring, so presumably the man was her husband. He was arguing with a porter; perhaps it would be more correct to say that he was listening to the porter argue. And the result, as I guessed instinctively it would be, was the complete defeat of the Brazilian porter, who retired discomfited and cursing volubly.

Then the man turned round and came towards us. He was considerably older than the woman—twenty years at least, and he did not impress one favourably. Thin-lipped, thin-faced—one glance at him was enough to explain the rout of the porter. Also perchance, I reflected, his wife's expression.

As he approached her she seemed to make an effort to become more animated. She forced a smile, and the two of them went below together, leaving me wondering idly as to their story. Perhaps I was wrong; perhaps it was the overpowering heat that had made her look like a dead woman. At any rate, I should have plenty of time to study them on the way home to London. And on that I dozed off.

The next time I saw them was in the smoking-room, before dinner. He was having a drink, she was not. They were seated in a corner, and during the five minutes I was there neither of them spoke a word. In her evening frock she looked fluffier than ever, whilst the black and white of his evening clothes seemed to enhance the severity of his features. And once again I found myself wondering what lay behind it. Was it merely the old story of youth married to age, or was it something deeper?

Once or twice it seemed to me that he was watching her covertly, and that she, becoming aware of it, tried to pull herself together just as she had done on deck that afternoon. And suddenly it dawned on me. Whatever might be the cause of her depression, she was afraid of him.

The Doctor joined me, and I drew his attention to them. "They've never travelled with us before," he said, "so beyond telling you that their name is Longman, I can't help. He looks guaranteed to turn the butter rancid all right, Incidentally, they're at my table."

And after dinner I met him on deck. "There's something rum in the state of Denmark," he said. "I can't make those two out at all. I don't know whether she's been ill or what it is, but she's the dullest woman I've ever met in my life. Even young Granger couldn't get a word out of her, and he'd make the Sphinx do a music-hall turn. Just Yes and No, and not another blessed syllable. Tell you what, Parsons, she's terrified of that husband of hers."

"Just the conclusion I came to before dinner." I remarked.

"Look there," he said quietly. "Granger has asked her to dance, and she's fumed him down. Well, well, it takes all sorts to make a world, I suppose, but I'm glad some of the specimens are rare."

"I must confess I'm curious about them," I said.

"I'm afraid you'll have to remain so," he laughed. "I don't quite see anyone prattling brightly to them at breakfast and asking them the why and the wherefore."

But as it turned out, he was wrong. The first passenger to board the boat at Rio was Charlie Maxwell, who metaphorically fell into my arms on sight.

"Bill," he shouted, "surely Allah is good! My dear old boy, I had no idea you were in these parts."

"Taking a voyage for the good of my health, Charlie," I said. "What's the matter?"

For Charlie had suddenly straightened up and was staring over my shoulder with a strange look in his eyes. "So they're going home, are they?" he muttered. "That's going to make it a bit awkward for all concerned."

I looked round; a few yards away the Longmans were leaning over the rail. And at that moment the husband saw Charlie. He gave a slight start, and then his face became as mask-like as ever. His wife saw him, too, and gave a cry of delight.

"Uncle Charlie!" she cried and took a little run forward.

"Mary!" The husband's voice, harsh and imperious, cut through the air and she stopped, biting her lip.

"How are you, Mary, my dear?" said Charlie quietly. "I'd no idea you were going to be on board."

"Mary—go below." Again the husband's voice, and after a momentary hesitation she obeyed, leaving the two men facing one another.

"I believe I told you, Mr. Maxwell," said Longman, "that you were no longer included in the category of my wife's friends."

"I rather believe you did, Mr. Longman," drawled Charlie. "And my answer was that you could go to blazes, and stay there. You would merely be anticipating the ordinary course of events."

Three or four passengers were staring at the two men curiously, and for a moment I was afraid there was going to be a scene. Their voices had been low, but their attitude was obvious. And then with a shrug of his shoulders Longman turned away and followed his wife.

"Let's go and have a drink. Bill," said Charlie, "and then I must make certain that I am not at that swine's table."

"They are at the Doctor's," I told him. "But why Uncle Charlie?"

"Needless to say, she is not my niece, but I've known her since she was two. There once was a time when, if things had gone differently, she might have been my daughter. Her mother died on her arrival, and I'm fond of the kid."

"The doctor and I were puzzling over the menage last night," I said.

"One night I'll tell you about it," he said gravely, "if you'll both give me your word that you won't pass it on. It's one of life's tragedies."

The opportunity occurred a few evenings later. We had most unexpectedly run into bad weather, which kept the Doctor busy, but things settled down again after passing St. Vincent.

Don't ask me why she married him,—began Charlie Maxwell as we settled ourselves in the Doctor's cabin—for I'm bothered if I know. I once asked her the question myself, and I don't think she knows either. As I told you, Bill, her mother died when she was born, and for some reason or other she never quite hit it off with her father. Funny thing, too, for he was a very decent fellow, but they just didn't agree.

He was a stockbroker and pretty well-to-do, with a nice house down near Surbiton. And since I bore him no malice, particularly after his wife died, for having been the favoured one, I used often to go down and spend the weekend with him and play golf. And it was because of that that I was given the honorary rank of Uncle. I watched her grow up from a little toddler, through the flapper stage till she reached the marriageable age. Of course, I was out of England a tremendous amount, but I generally saw her two or three times a year. And you two fellows who have only seen her on board here—listless, silent, dead—will hardly believe what she was like then. To say that she was the life and soul of any show she was at is to state no more than the bare truth.

She was a topper, and the boy friends realised the fact. But strangely enough, in spite of her relations with her father, she showed no signs of accepting any of them, though I know several of 'em asked her. She used to bemoan the fact to me that they did so. 'It's never quite the same after you've given them the push' she said. 'And I don't want to get married for a long while.'

Judge, then, of my surprise when I came back to England a couple of years ago to find that she'd gone and done the deed. It was her father who told me when I met him in the club one day, and I could see at once he wasn't too pleased about it. 'Women beat me, Charlie,' he said. 'There's Mary, with a dozen fellows of her own age to be had for the lifting of a finger, goes and marries a man of our age. Financially he's a good match, and he seems devoted to her, but he ain't my idea of fun and laughter. Come down this week-end and have a look at him yourself. They're both stopping with me.'

'What's his particular worry in life?' I asked him.

'He goes in for research work,' he told me. 'He qualified as a doctor, and then some aunt died and left him a lot of money. So he doesn't practise, but devotes himself to original work on his own. A clever fellow.'

Well, I went down, and I got my first inkling into Mr. George Longman's character shortly after my arrival. Mary, as was her invariable custom, gave me a kiss, and I happened to see his face just after. And I was not surprised to overhear a remark a little later which was not intended for my ears.

'What nonsense, George,' she was saying, 'I've known Uncle Charlie since I was born.' I did not hear his reply, but the subject of their conversation was not hard to guess, and it did not start our relations too auspiciously. Of course, I was his age and all that sort of thing, and she was his wife, but for all there was to it I might really have been her uncle. Naturally, nothing was said about the matter, and neither of them had any idea that I had overheard. But—there it was.

Now both you fellows have seen Longman, and he was just the same then as he is now. He could talk well when he chose to on a variety of subjects, but it always seemed to me that behind all his conversation was a cold, analytical mind. Never once would he allow an argument of his to be influenced by the milk of human kindness. Sentiment had no place in his mental equipment; a thing was either proven or non proven. And the more I saw of him the more did I share her father's surprise at Mary having married him. On the surface she seemed happy enough, and he, in his peculiar and rather precise way, was undoubtedly very much in love with her. But on the second day after my arrival the rocks ahead began to show pretty clearly.

Her father, as usual, was in London, and at lunch I suggested a round of golf to Mary. There was no question of a three-ball, as Longman didn't play. To my intense surprise she looked rather hesitatingly at him, and asked him if he objected. And to my even greater surprise it was quite clear he did object. He didn't say so. Knowing who I was, and the terms I was on with the family, he hadn't the face to. But his consent to our round very nearly congealed the fish on the sideboard. So I tackled her about it on the way up to the links. 'Look here, Mary, my child,' I said, 'that husband of yours seems to have a nasty mind. Does he think I'm going to kiss you on the first tee?'

For a while she didn't answer; then it came out with a rush. 'It's awful. Uncle Charlie,' she cried. 'His jealousy is something unbelievable. Do you know that this is the first game of golf I've played with a man since my marriage?'

'Great Scott!' I said. 'I thought people like that only existed in books. What does he think you're going to do on a golf-links?'

'And it's not only that,' she continued. 'It's the same over everything. Dancing, for instance; he has a fit if I dance with anyone else. And as he doesn't care about it himself, there's simply no good going to one.'

We drove on in silence for a bit, and it was then that I asked her why she married him. Couldn't help it; that question just had to be put. And as I told you before, I don't think she knew herself. I think, perhaps, she'd been flattered a bit by a man of his brains running after her. Possibly before they were married he'd been a little more human. Anyway, that was the state of affairs two years ago. Now we're coming to the point.

The branch of research in which Longman was most interested was toxicology, with special reference to snake poisons. And he had undoubtedly studied the question very thoroughly. But he was very anxious to go for a time to some place abroad where he could observe the brutes first hand. And he started pumping me on the matter. I told him that all I knew about snakes was that they made me move quicker than anything else, but that for variety of specimens, each one more pestilential than the last, Brazil was hard to beat.

Then one of those extraordinary things happened that makes one wonder who pulls the strings. The very morning after we'd been talking about it I got a letter from a pal of mine telling me that he was going out to Brazil on some form of experimental work connected with snake bites and their antidotes. It was a semi-Government job, a bit up-country from Rio, and would I look him up next time I was there? It was such an amazing coincidence that I threw the letter over to Longman to read.

'If that's any use to you,' I said, 'I can easily give you an introduction to the writer.' He was delighted, and accordingly I asked them both to meet at my club, left em together, and forgot all about it.

A few months later I butted into Mary walking down Bond Street. I hadn't seen her in the interval, or her father, so I suggested lunch. 'Or,' I said jestingly, 'will George object?'

'George is in Brazil, Uncle Charlie,' she answered with a smile. 'So it will be a bit late if he does.'

'So he went, after all!' I cried. 'I'd forgotten all about it. Perhaps I shall see him out there.'

She clapped her hands together. 'You aren't going, are you?'

'Next week,' I told her, 'by the good ship Oregon.'

'But it's too wonderful,' she said. 'So am I. You'll be able to help me through all the difficulties.'

I laughed. 'The difficulties, my child,' I assured her, 'of going from London to Rio will not turn your hair grey. Now tell me all about what George is doing.'

Well, it appeared that George had gone out with this other fellow, leaving Mary to follow him if accommodation was suitable. The place seemed to be a sort of glorified snake farm, and they were carrying out experimental work with antidotes. George was there on his own in an unofficial capacity, and he had managed to obtain a house not far away. I knew the country near, though not the exact spot, and I was able to assure her that she would not be eaten by cannibals or lions, nor would she find an alligator in her bed. And ten days later the Oregon sailed, with us both on board.

Now, we who go down to the sea in ships for most of our lives have probably forgotten the ecstatic thrill of our first long voyage. And it was her first long voyage. Moreover, dear George's influence had been absent for some months. The result was what one would have expected; she was as excited as a dog with two tails. She danced every night; she played deck-tennis every day, and except at meals I saw very little of her. I was working on a report and my nose was pretty well down to it. A pity, because I might have spotted it sooner, though I don't know if it would have done much good if I had.

There was on board a youngster called Jack Callaghan, and a more delightful boy it would have been difficult to meet. And one morning—it was after they'd triced the tarpaulin up for a swimming bath—I happened to be strolling round the deck. It was early—before breakfast—and there were very few people about. But a splash in the pool below made me look over, and there were Mary and young Jack having a bathe. They were alone; they didn't see me, and they were ragging in the water. Then they got out and sat down side by side, and I was on the verge of calling out to them when he covered her hand with one of his and kissed her shoulder.

And Mary, to put it mildly, did not resent it.

I don't know why it came as a bit of a shock—my morals are fireproof. I suppose it was because it was Mary. However, I withdrew discreetly, and decided to keep my eyes open. Ship-board flirtations are so common and so harmless that I didn't anticipate any trouble, but I thought I'd watch 'em. And I very soon found out that this was a bit different.

It was later that very morning, in fact, that an elderly harridan with a face like a wet umbrella conceived it to be her duty, since I was Mrs. Longman's uncle, and though, of course, I would understand that she didn't want to make mischief, to tell me in the interests of all concerned, though really it was nothing to do with her and she was only too glad to see young people enjoying themselves, but that she was sure I wouldn't mind her mentioning that my charming niece was being a little indiscreet.

I didn't enlighten her on the relationship question, and pooh-poohed the whole thing. But in the course of the next two or three days I realised that the old woman was perfectly right. They were the talk of the whole ship. Literally, they were never out of one another's pockets. And I decided that it was time I did something. So I buttonholed Mary.

'Look here, my dear,' I said, 'for a few moments I'm going to be an uncle in reality. Have you forgotten that you're going out to a perfectly good husband?' I could see she understood, though she pretended not to at first. 'Your come-hither eye with young Jack is the one topic of conversation on board ship,' I went on. 'Do you think you're being quite fair to him—because it strikes me he's got it badly.'

And then she admitted it; they were in love with one another. Her marriage to George had been a hideous mistake, and all the usual palaver.

'It may have been, my dear,' I said, 'but it's a mistake which, unfortunately, cannot be rectified. Are you really serious about this, or is it just a bit of ship-board slap and tickle?'

Evidently it was not, and I began to foresee complications. What did they propose to do about it? I asked. They hadn't got as far as that yet, she told me, and I breathed again. In all probability they would never see one another again after we reached Rio, and the man who said that absence makes the heart grow fonder coined the most idiotic utterance in the language. But there was one thing that had to be seen to, and I tackled Callaghan that night. 'Look here, young feller,' I said, 'I want a few words with you. I hope you'll take em the right way, and not regard me as an impertinent outsider. Mary has told me how things are, and I'm extraordinarily sorry for both of you. However, it can't be helped. You've got to grin and bear it, as lots of other people have done before you. But I'm going to ask you to do one thing—a very important thing—a thing for Mary's sake. She, I assume, has told you about her husband, the manner of man he is. Well, I can confirm what she says. Without exception he is the most jealous individual I have ever met. Now almost certainly he will come on board to meet his wife at Rio, which brings me to the point. I do not want there to be the slightest possible chance— don't forget he's got an eye like a gimlet—of his spotting that there is anything between you two. So, for the love of Allah, get your good-byes over the night before we arrive, and behave as casual acquaintances in front of him. No sighs and soulful glances—for if he intercepts one he'll make her suffer for it afterwards.'

'The swine,' he muttered. 'Oh, how I wish I could ask her to come away with me, but I can't arrive at Cadaga with her in tow.'

'Where did you say?' I said slowly. 'Cadaga! My sainted aunt!'

'What's the matter?' He stared at me in surprise.

'The matter, my young friend,' I said, 'is that that has put the lid on it. Cadaga is not five miles from where Mary is going. I had hoped that several hundreds were going to be between you. Brutal, I admit, but far safer.' They hadn't realised it, of course; the geography of the country was unknown to them. And their reaction was wild joy. Mine was not. But there was nothing to be done about it. I talked to them both as seriously as I could, but what was the use? They promised to be careful, and see one another as little as possible, but with a man like Longman the only hope would be if they didn't see one another at all. However, as I say, there was nothing to be done except let matters take their own course and hope for the best. Doc, I'll have a spot of that whisky of yours.

It was four months later—continued Charlie Maxwell— that I picked up the threads again. Longman had met her at Rio as I anticipated, and Jack Callaghan, realising that it wasn't good-bye, had treated Mary with a casual indifference that satisfied even me. But a lot could happen in four months, and being in their vicinity I decided to look them up and see if anything had.

I arrived at Longman's house in the afternoon, to find Mary alone. He was down with his snakes, so we could talk freely.

'It can't go on, Uncle Charlie,' she said dully. 'Jack and I both realise that now. He's coming over tomorrow, and I'm going to say good-bye to him and tell him he mustn't come over again.'

'Poor kid,' I said. 'I'm frightfully sorry for you, but it does seem the only solution. Have you seen much of him?'

'Half a dozen times,' she answered. 'That's all.'

'And George doesn't suspect?'

'Oh no! He hasn't an idea. He never will have.'

'Well done,' I said. 'For I don't mind telling you now, Mary, that I've been devilish uneasy as to what was going to happen.'

And it was a fact—I had been. I had not thought it possible for those two to see one another and not give the whole show away, which, with a man of Longman's nature, would have spelled disaster. But when he came in and we started dinner, I had to admit that on the face of it Mary was quite right. He was exactly the same as ever, cold and precise to me, courteous to her. He talked in an interesting way of experiments he was carrying out, and by the end of the meal my fears were quite allayed. And then in a flash they returned. Mary had left us, and he had just lit a cigar. I don't know why I watched the operation particularly, but I remember thinking how typical it was of his character. The meticulous care with which the end was cut the delicate way the used match was deposited in the ash-tray; the slow exhalation of the smoke—in each separate movement one saw George Longman, who was now staring fixedly at me.

'Did you,' he said, speaking with extreme deliberation, 'see much of a young man called Callaghan on the way out?'

The question was utterly unexpected, but a kindly providence has endowed me with a face which enables me to win more money than I lose at poker. And I'll guarantee he got nothing out of me.

'Callaghan,' I answered thoughtfully. 'Callaghan! I remember him. A nice boy, who was always running round after some girl whose name I forget. Why do you ask?'

'He is on a plantation close to here,' he remarked, 'and has been over to see Mary once or twice. You forget the name of the girl, you say.'

'Completely,' I answered. 'She didn't get off at Rio, but went on to Buenos.' And speaking, knew that he knew I lied.

But his voice as he continued was quite expressionless. 'He has seemed very interested in some of my experiments. Strange, too, for I have never met a human being who is in such mortal terror of a snake. It is worse than terror, it is a peculiar revulsion which comes over him if a snake is near him, even though it is shut up in a box. And so, as I say, it is strange that he should go out of his way to accompany me to the farm!'

'Perhaps he is trying to overcome it.' I said casually. I couldn't get his line of country at the moment, though it was clear Mary and young Jack had been living in a fool's paradise.

'Perhaps,' he agreed. 'Or there may be some other motive; who knows?'

'Motive?' I said. 'A rather strange way of putting it, isn't it, Longman? It may surely be that he thinks it only polite to show an interest in your hobby.'

'Politic I think is le mot juste.' he remarked, and I knew the blighter had spotted it. Jack Callaghan wasn't going trotting round a snake farm when he might have been with Mary, unless they'd both deemed it wise. The trouble was that it evidently had not deceived Longman.

'Politic,' he repeated, as if the word pleased him. 'It's astonishing how blind some people can be, Maxwell. Are you quite sure that the girl whose name you forget went on to Buenos?' He didn't wait for an answer, but pushed back his chair and rose. 'You'll excuse me if I leave you,' he continued, 'but I am in the middle of an experiment down at the farm, which I must return to.' He went out through the open window, and for a while I sat on at the table. He knew; there was not a shadow of doubt about it. And the sooner Mary was aware of the fact the better. I didn't like his manner. I'll go further and say I was frightened of his manner.

And yet, I argued with myself, what could he do? Clearly, Jack must never come over again, whatever construction Longman might put on it. And I began to wonder if that was what he had been playing for. If he had gone straight to Mary or Callaghan, it might have precipitated a crisis he was anxious to avoid. And so he had adopted the roundabout method of sending them a warning through me.

At first Mary wouldn't believe me when I told her that he suspected her and Jack. It was perfectly true that Callaghan had been two or three times to the snake farm, because they had both thought it advisable, but what was there suspicious in that? And it wasn't until I metaphorically shook her, and made her understand that I wasn't inventing it, that she began to realise the situation. Like all people in love, she had blissfully believed that no one else knew, and now she had to adjust her outlook to include the fact that the one person of all others she wanted to keep in ignorance was fully aware of her secret.

'It won't matter after tomorrow,' she said a bit pitifully. 'I don't suppose I'll ever see Jack again. And we couldn't help falling in love with one another, could we?'

'Look here, my dear,' I said, 'I don't want to be brutal, but must there be tomorrow? Can't you put him off?'

'And not say good-bye!' she cried indignantly. 'How can you suggest such a thing? Besides, George knows he's coming.'

There was no more to be said and I let the subject drop. But I was uneasy. Try as I would I couldn't get rid of a premonition of trouble. For a man of Longman's nature to know his wife was in love with another man and not forbid that man the house, seemed amazing to me.

Charlie Maxwell paused and lit a cigarette.