8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

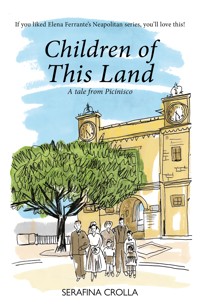

The moving and delightful story of the Valente family, although fiction, is grounded in first-hand knowledge of the way of life in Picinisco, southern Italy, in the post-war years. Poverty, separation and loss were common experiences that caused many to emigrate. Yet the hardships were more than balanced by a culture of family warmth and vitality, shared connection to the land and an intimate understanding of how to work it. A born storyteller, Serafina Crolla was inspired to write Children of This Land when visiting the cemetery in her native village of Picinisco. There, she saw a headstone for 'An exemplary mother of nineteen children'. She was deeply struck by the eloquent simplicity and poignancy of this memorial inscription. As the daughter of a shepherd, Serafina well understood the joys and hardships that life would have entailed for this family. Through the vicissitudes of life, ties to this place hold strong for the Valentes. The nineteen children who make up the family tell their stories of love, marriage, trials and tribulations, loss and pain of immigration. Serafina's own family emigrated to Scotland when she was a little girl but she returns to her homeland often, for, as she puts it: 'A love for Picinisco as deep as the valleys and as pure as the snow-capped mountains is never forgotten.'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

SERAFINA CROLLA is a wife, mother and grandmother who lives between Edinburgh and Val’ Comino in the province of Frosinone in Italy. Born in Picinisco in the foothills of the Abruzzi mountains, the daughter of a shepherd, she has lived an unusual life.

By the same author:

The Wee Italian Girl (Luath Press, 2022)

Domenica (Luath Press, 2022)

This is a work of fiction; any similarities to any person alive or dead are coincidental.

First published 2023

ISBN: 978-1-80425-143-0

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 12 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© Serafina Crolla 2023

In memory of my beloved brother Vincenzo, who fought bravely against COVID-19 but lost his life.

Contents

Valente Family Tree

Foreword

CHAPTER 1 The Family

CHAPTER 2 The Tarttaglia Family

CHAPTER 3 Andrea. Francesco. Pietro.

CHAPTER 4 Andrea Has a Problem

CHAPTER 5 Teresa Goes to the Palazzo

CHAPTER 6 A Nun’s Story

CHAPTER 7 A Letter from America

CHAPTER 8 Matilda’s Baby

CHAPTER 9 Matilda is Feeling Blessed

CHAPTER 10 Teresa

CHAPTER 11 Smallpox

CHAPTER 12 The Boys

CHAPTER 13 Osvaldo

CHAPTER 14 She Wanted to be Dead

CHAPTER 15 Maria Comes Back

CHAPTER 16 Teresa Again

CHAPTER 17 Festa Time

CHAPTER 18 Wedding Plans

CHAPTER 19 Francesco

CHAPTER 20 Giovanni

CHAPTER 21 They Come to a Decision

CHAPTER 22 Stefania

CHAPTER 23 Catarina

CHAPTER 24 Ten Years Later

CHAPTER 25 Andrea Comes Home

CHAPTER 26 Back from America

CHAPTER 27 Family Reunion

Afterword

Valente Family Tree

Foreword

CLOSING HER TRILOGY on her native country with Children of This Land, Serafina Crolla reconfirms herself as a talented writer and storyteller, shaped by Italian and English matrices.

Taking her cue from one real fact, the epitaph on the tomb of a mother of nineteen children, she imagines the lives of the Valente family in a series of stories set in the 1950s and grounded in the realities of life in our territory, Val Comino, in the aftermath of war.

Among the many vicissitudes of her unfolding tale, the conflict between the long-established customs of rural families and the rapidly altering socioeconomic conditions brought by the mid-1900s comes into sharp relief. The Valentes’ lives offer few resources, sustenance comes only with hard manual labour and poverty is a recurring threat, and yet the times are bringing new fashions, innovations and an individual dilemma that threatens to tear families apart: should they leave or stay?

Within the struggles of the Valente family, we find the whole condition of life of these times writ small: the ways of thinking, the old and new customs, the rhythm of everyday life and the interruptions of unforeseen events, positive and negative. We find the circumstances that prompted some to emigrate, prevented others from doing so, and made others still choose to stay.

Serafina brings us intimately into the experiences and aspirations, the thoughts and feelings, of both the younger family members and those of the adults who support them with a narrative freshness that captures the nuances of each, profoundly drawing out their individual psychologies. Her humanity closes the gap between past and present with characters that move us, have fun and leave us to reflect on the meaning of life’s many events, the wisdom of knowing how to live even in the midst of tough choices.

This book is a treasure trove of special moments brought to life by dialogues painted with objectivity and honesty. Serafina makes us become attached to each character, each co-protagonist, arousing empathy and sympathy in these many intersecting lives and creating an interest in their various situations, trades, decisions and hidden desires which stays with the reader until the end – this is what makes Serafina a great storyteller.

Now we can only wait for the next novel that her fervent creativity will give us – perhaps one that takes us into the mists of Great Britain.

Maria Antonietta Rea, author of Uno e 50

CHAPTER 1

The Family

IT WAS NOT long ago that country people in Valle di Comino in central Italy were illiterate. Before the Second World War, children had some education, at least to be able to read and write. Then war brought misery and hunger. There was no time for school where this story is set, in the town of Picinisco. This area of Italy had been very much affected by the Battle of Monte Cassino. With many civilian casualties, it had taken ten years for things to return to normal for the citizens of the valley. The country people did not know much of the world; some did not even know what was over the mountains. Their whole world was their house, their brothers and sisters and extended family. They knew all about the surrounding towns and villages, and all the family connections, because, to them, talking was a pleasure and a pastime. Aside from the local gossip, they got to know things that would help them to make a living.

This tale is about a large family: a mother and father, his parents and her mother, and their sixteen children. Andrea, the eldest, was twenty-four years old. Concettina, the eldest girl, was twenty. She had nine brothers and seven sisters. Bruno, the youngest, was two, and the mother pregnant.

How they lived was simple; they had the basics of life, the very basics. To put food on the table every day for twenty-one souls was not easy, but it was a joint effort. It meant everyone had something to do, from the youngest to the eldest. They scraped a living in their few acres of stony land, with their few animals. To keep these animals alive was a constant fight and the temptation to eat them was also a struggle.

In comparison with their neighbours, their house was big enough. It had four rooms downstairs, four rooms on the first floor and attic where they stored their grain. The house did not belong to the family, but to the mother’s brother Alfonso, who had emigrated to America. After five years they heard nothing more from him, so his sister, with an ever-growing family, decided to move into the house with the approval of her mother.

The ground floor of the house had a very large kitchen, with a fireplace and a brick oven in one corner. In the middle of the room there were two huge tables placed end to end with chairs, stools and benches, but still there were not enough seats for the family. The very young children sat on the floor to eat their meal. The rest of the ground floor rooms were used to stable the animals and to store firewood, hay and foodstuffs.

Of the four rooms upstairs, only three were usable – the other room was open to the elements, with no window panes and a hole in the roof. It was fortunate that the rooms were all large because to accommodate such a large family, young and old, was not an easy task. But at least they were warm with the heat that came from their bodies; they slept close, man and wife.

Vincenzo Valente and his wife Matilda slept in one room with the baby in their bed and the twin girls, Erica and Lia, were squeezed into the crib which they had outgrown long ago. Baths were an unheard-of luxury. The girls would take a large basin of hot water to their room and wash all over with a cloth and rough soap – and where they could not reach, there was always a sister to help. The life of the children at home was like a chain reaction: each was one of the links and those just a little older would help the younger ones. They were not really brought up, they were dragged up. How could it be otherwise? How could the parents cope with sixteen children and another on the way? God bless them all.

The family had a few acres of land in little patches here and there, some so far away it would take all morning to get there. But time was one thing the family had. Three or four of the siblings would set off and what needed to be done was done, after which they enjoyed a leisurely walk home. On their way, they would meet others – there was always time for fun, games and catching up with friends.

Everyone had a job to do. The grandfather and grandmothers kept the fire going, chopped wood, gathered tinder, fed the hens and the pigs: that was their domain.

Concettina and her sister Maria would help their mother to make bread every three days. The mother would oversee the task, making sure that everything was done to her liking. But it was the girls that would knead the heavy dough, one at one end of the deep wooden trough, one at the other end, four hands pulling and stretching, the warm dough up to their elbows. Sometimes they would stop to straighten their backs, wipe the sweat from their flushed faces, then carry on until the dough was ready for its first rest. It was covered with a warm blanket until it was ready for its second kneading, then made into large two-kilo loafs, covered with the blanket again and left to rise. In the meantime, Nonno Andrea would light the huge brick oven and feed it with bundles of twigs, the prunings of the olive trees and a few chunks of heavy wood to keep the fire going until it was the right temperature to bake the bread.

The father would make sure that they cultivated their plots of land to the fullest. He would send a squad of the younger children to remove surface stones before ploughing. Then, after ploughing, the children would go again to remove all other stones that the plough had turned over. Some were so big that it took two strong boys to carry them to the edge of the field; these bigger stones were left there to reinforce the supporting terrace and stop their land from sliding down the hill. Then it was up to the children to dig with spades, right up to the edge of their property, so as not to waste a single inch of their land. Land was bread and bread was life.

The women at home were tasked to prepare two meals every day for the large family. It was never ending. The family would return to eat no matter where they happened to be.

CHAPTER 2

The Tarttaglia Family

BECAUSE THERE WERE so many mouths to feed, the Valente family also worked ground that belonged to the local landowner. Don Stefano came from a well-to-do family that had owned an estate in the area for centuries. It was said that his family originally came from Spain and that they were gifted the estate from the King of Naples. Whether this was true or just a legend nobody knew, but it made no difference – when the men passed him, they tipped their hats and the women curtseyed.

The Tarttaglia family lived in a palazzo (mansion) on the top of a hill. Lime trees lined the road that led to its iron gates. The gates were always open so that wagons and carts full of produce could pass through to its grain store. The silos were full to overflowing on good years and nearly empty on bad years. Some years, the farmers would have no money to buy the seed to sow the land, and the factor would give them some, for which they would pay when the new harvest came in. This would happen again and again until the loan was called in, and the only way to pay it was to sell a piece of their own land at a rock bottom price to the Tarttaglia family until there was nothing left, leaving farmers totally dependent on il signore on the hill. Then whatever they produced on the land that they had once owned would be halved. It was back-breaking work to produce enough for their large family and enough to fill the landlords’ coffers to overflowing.

Some farmers had to abandon the land altogether and work as labourers for the estate. But it was always as day labourers; if there was work, they would be paid, if not, there would be no pay and they would have to look elsewhere, a day here, a day there. Sometimes they went further afield, as far as Rome or over the Abruzzi mountains to Pescasseroli, doing seasonal work: picking grapes, scything wheat, harvesting potatoes or gathering olives. The men would come back on Sundays to pass on their meagre wage to their wives. Then they would go back again on Monday.

The bodies of the men were scrawny, sun-baked and dark. Their teeth were black from smoking rough tobacco. But if they were in good health, there was always a twinkle in their eyes and if there was a laugh to be had they were ready for it. And when they went back home, they would enjoy their wives. The young men were virile and fertile and another child to feed would be conceived.

That year there was seed. Vincenzo was behind the plough and his two cows were attached to the harness, pulling with all their might and turning the earth over ready for the seed. His sons Andrea and Francesco followed behind, breaking up the clods of earth. Giovanni was leading the animals, pulling at the halter, and his sister Teresa and his younger brother Osvaldo were turning over the earth. It was hard work, back-breaking work; the sun was hot and tiring. Teresa kept looking at the sun – it was surely midday, time for her mother to bring food.

Eventually, Teresa saw three figures walking towards them in the distance, her mother and younger sisters, Stefania and Fiorinda. The workers put down their tools and made their way to the edge of the field where there was some shade.

Matilda and her daughters arrived and set down the basket that they carried. Food for them, and hay and water for the animals. Andrea and Francesco saw to the beasts while their mother ladled the food onto plates. Sagne e fagioli, homemade pasta with beans, and a few stray bits of cotechino, rough pork sausage made with pig skin. This was, of course, followed by bread and cheese.

The family made themselves comfortable to eat. They were always hungry; although food was plentiful, the sheer number in the house made it impossible for them to feel truly satisfied. When they finished, Vincenzo took his tobacco and paper out of his pocket. Slowly and skilfully, licking the paper with the tip of his tongue, he made a perfect cigarette. Andrea, his eldest son, looked on greedily. If only he could have one too, but his father did not know that he smoked whenever he could get one. If he asked his father for a cigarette, he would get a blow on the back of his head. Vincenzo, although he was a smoker himself, did not want the boys to get into the habit. He was always telling them that it was bad for their health and for their pocket.

Vincenzo inhaled deeply, blowing the smoke out of his nose.

He finished his cigarette, threw the stub away and got up to resume ploughing the land. The boys followed him, disappointed, because usually they could lie down in the shade and rest a little after their meal before they went back to their toil.

Matilda called him back. ‘Vincenzo, on my way here I met Don Pasquale. He said that he had spoken to Donna Tarttaglia – she asked him if he knew of a good clean girl to work at the house as a maid and he has suggested Teresa. I said to him that I was sure that Teresa would be very happy to go, what do you think?’

Teresa was looking from her mother to her father.

‘Yes, yes! I want to go!’ she exclaimed. Anything to get out of the house.

Her mother ignored her and spoke again to her husband, ‘What do you think?’

Vincenzo’s first thought was yes, one less at home, but, on reflection, he did not know if it was a good idea. He looked at Teresa – she was the prettiest of his girls. Fresh face, a golden glow to her skin, plenty of dark hair and a good figure. Would she be safe away from home?

‘Do you want to go? Remember, if you do, you will be at their beck and call all day. It won’t be like when you are at home where you please yourself and avoid chores if you can. All I hear when I am home is your mother calling you – you are never there when you are wanted.’

‘Yes, Papà, I want to go. I am sure I will learn many things in the big house, and I will work really hard, make myself indispensable to Donna Tarttaglia, you will see. I will make you proud of me.’

‘All right, then go, you know your way home.’

His wife then said, addressing Teresa, ‘The priest said that he will come tomorrow morning, he will take you to the house. La signora wants to see you first.’

Seeing her daughter’s excitement, Matilda raised her eyebrows and added with a wry smile, ‘Don’t get your hopes up too high, she may not like you when she sees your capo alerto, arrogance.’

Teresa implored first her father then her mother with a look. ‘Please can I go home now to get ready?’

Her father looked at the flushed, excited girl with her good looks and charming way. She always got what she wanted.

‘If you must, then go.’

Matilda and Teresa packed away the remainder of their meal and went home, where Teresa spent the rest of the day getting ready. She washed her hair and prepared the clothes she wanted to wear the following day, hoping to make a good impression on Donna Beatrice. The rest of the family slowly made their way back to their work.

Andrea was in a foul mood. He picked up the rake and pulled and pushed at the clods of earth, smoothing the soil into a fine tilth ready for the wheat seed.