Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

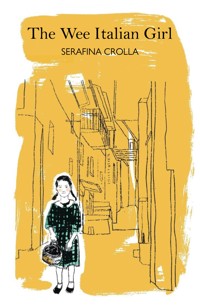

An ancient way of life. Living with nature and the seasons. Moving from high mountain to plain. The cleanest air and water, the purest food and wine. A little girl tells the story of her last year at home high up in the Apennines of Italy. The love of her family and neighbours. The conviviality and shared purpose of her tight knit community. The beloved grandmother she will leave behind as her parents head for the factory floors and restaurant kitchens of 1950's Edinburgh. An immigrant's tale but also a record of a simpler life. At one time negated and cast aside and now more than ever sought out and admired. The Wee Italian Girl is a document for many Scottish Italians who, apart from picturesque villages and majestic mountains wish to really know from whom and where they came.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 199

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SERAFINA CROLLA is a wife, mother and grandmother who lives between Edinburgh and Val’ Comino in the province of Frosinone in Italy. Born in Picinisco in the foothills of the Abruzzi mountains, the daughter of a shepherd, she has lived an unusual life.

First published 2018

This edition 2022

ISBN: 978-1-80425-021-1

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 12 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Serafina Crolla, 2018

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

CHAPTER 1 Once Upon a Time there was a Girl

CHAPTER 2 A Springtime Return

CHAPTER 3 Summer School

CHAPTER 4 Communion

CHAPTER 5 Going to Feed the Dog

CHAPTER 6 Blind Man’s Buff

CHAPTER 7 Tied to the Table

CHAPTER 8 Mother Is Never Wrong

CHAPTER 9 Fortunato Falling Off the Horse

CHAPTER 10 Potato Harvest

CHAPTER 11 Playing with the Boys

CHAPTER 12 Just a Bad Dream

CHAPTER 13 Doing the Washing

CHAPTER 14 The Water Carrier

CHAPTER 15 L’ Arca

CHAPTER 16 Canneto

CHAPTER 17 Zia Chiarina

CHAPTER 18 To See and Be Seen

CHAPTER 19 Going for Firewood and Eating Blackberries

CHAPTER 20 Going to the Orto

CHAPTER 21 Eagle (Arpé)

CHAPTER 22 Going to a Wedding

CHAPTER 23 All Able-Bodied Men

CHAPTER 24 The Sheep Return

CHAPTER 25 It Was Like a Highway

CHAPTER 26 Dad Leaving

CHAPTER 27 Going for Wine

CHAPTER 28 All Souls’ Day

CHAPTER 29 Going to the Mill

CHAPTER 30 Her Heart Fluttered

CHAPTER 31 Killing Mr Pig

CHAPTER 32 Sitting by the Fire Daydreaming

CHAPTER 33 A Time of Waiting

CHAPTER 34 Peppa

CHAPTER 35 Journey to la Scozia

CHAPTER 36 They Were Lucky

CHAPTER 37 Erica

Acknowledgements

I WOULD LIKE to thank Roland Ross, Monia Pacitti, Jennifer Alonzi, Maria Sarole, Luca Franchi and Nicola Sommerville for their help and computer skills. Also my copy editor, Louise Carolin, and Kavel Rafferty for her illustrations.

My son Remo and my daughter Maria Cristina for being the light of my life.

In memory of my father and mother, and all the rest who have gone to the village in the sky.

Foreword

THIS IS A story about an eight-year-old girl who lives in the mountains of central Italy, in the Abruzzi foothills. She is the daughter of a shepherd and lives with her family: her mother and father, her two brothers and her grandmother. They live on the mountains in the summer and move to the plains of Valle Comino in winter. This is the tale of her last summer in the village of Fontitune in the late 1950s, before she moved to Scotland with her family, leaving her beloved Nonna behind.

The girl still lives in Edinburgh with her family. She now has a granddaughter of her own who is eight years old. She tells her stories of when she was a child in Italy. ‘Nonna, tell me a story,’ her granddaughter often says.

So this book is for Erica.

CHAPTER 1

Once Upon a Time there was a Girl

ONCE UPON A time there was a girl who lived high up on the side of a mountain. Her name was Serafina. She lived in a village where there were no shops, not even a church, but there were about forty householders who made their living there. The village had one stony main road that went straight up; the houses were all attached in two long terraces with families on both sides.

The girl lived about halfway up, where there was a gate then a flight of steps on to a small terrazza, and then the front door. The house had three rooms: the first was the kitchen, at the back another room and then, up a flight of steep wooden steps and through a hatch, the bedroom that her mum and dad slept in. In these three rooms lived the girl, her mother and father, her nonna (grandmother) and two brothers, Fortunato and Vincenzo, one older and one younger.

Under the house there was the stable, which housed a grey horse, a grey pig, ten red speckled hens and one big strutting rooster. Outside of the stable there was a small courtyard where the hens scratched all day. This was the household of the girl.

I almost forgot; there were also two hundred sheep and three dogs, but most of the time they were in the high pasture in the mountains for the summer. The family would spend the summer in their home on the mountain and in winter they would go to the plains; the whole household would move. The plains were known as ‘down-by’, the mountain village, ‘up-by’.

CHAPTER 2

A Springtime Return

IT WAS SPRINGTIME; the girl was on an old rusty truck which took the bends on the road at great throttle. They had been on the road travelling since early morning. The girl felt as if her body was out of control, being thrown this way and that as the truck roared uphill.

She was sitting in the cabin with her mother, Maria, who had her little brother Vincenzo on her lap at the front with the driver. Serafina was squeezed in behind her. In the back of the truck there were all their belongings, including a big cage full of hens, a table and chairs, beds, pots and pans. It was all covered with a great cover; they were going home.

Eventually after huffing and puffing, stops and starts and a great push, they came to a town and stopped. The girl looked out of the window and she could see the mountains of home. They still had snow at the top.

‘Nearly there,’ said her mother.

Her mother put her brother, who was sleeping, on the seat and got out of the truck. She went to the back of the truck to fetch a pail and rope and walked away.

The driver asked the girl if she wanted to get out while they waited for her mother, but she shook her head. She knew without being told that whenever her mother was not there she had to look after her younger brother. After a while her mother reappeared; she was leading a little pig who had its nose in a pail of corn. She went to the back of the truck, picked up the squealing pig and put it in, tied the rope to the side of the truck, put the pail of corn in front of its nose and left the pig happily eating. The driver jumped in and they were off again: down, down they went until they came to a high road; from the window, she could see her mountains.

Eventually it grew dark, and started to rain. She fell asleep.

‘Wake up.’ Her mother shook her; they had arrived.

The rain was still falling. She could hardly stand. She was so tired. She cried. Her brother cried. The pig squealed. Her mother took her by the hand, she carried the baby and pulled the pig on a lead. They had to walk up the steep, rutted road. They came to the house. The pig was put in the stable, the children on the doorstep; her mother covered them both with a blanket and told them to stay there until she came back. They sat on the steps and cried; wet, cold and hungry.

It seemed an age before her mother came back. She appeared with the cage of hens on her head. There were other people too who were carrying things. Then her mother produced a big black key and opened the door, quickly taking them to the back room where she stripped them of their clothes, dressing them in dry vests and pants, and put them to bed. Serafina’s head touched the pillow – she was asleep.

In the morning she woke up and went into the kitchen where she found her nonna, and most of their things piled up in the middle of the floor. Her nonna was heating milk on the open fire. She cut thick slices of bread off the huge round loaf, put them on a dish and poured the hot milk on top, sprinkled them with sugar, and put it in front of the girl. The girl wolfed it down.

She went outside on the small terrace and looked at all the familiar things. She felt so happy, but did not know why she was happy. Now all she had to do was wait for her dad, her brother Fortunato, the grey horse, two hundred sheep, and three dogs to arrive and they would all be at home. They were making the return trip to the village on foot and it would take them three days, following centuries-old tracks.

CHAPTER 3

Summer School

WITHIN A WEEK, all the families of the village had made the return journey to their homes in the mountains. The girl was playing from morning till night. So much to catch up on! Her cousins and friends, all the children of the village, seemed to have grown overnight and it took a while before she got used to them being the same people she had left in the winter.

Her best friend was her cousin Rita. They were the same age, although you would not think it to look at them as Serafina was a big strapping girl and Rita was small and very thin. Rita lived just outside of the village in a new house. It was called L’ara Cullucia. The girl went there often, either to stay and play or to call Rita to come to play in the village if there was a good game going on. This day, the girl was going to see her uncle, Rita’s father, to give him a message from her father. When she walked into the kitchen there were people seated round the table. Strangers! A beautiful young woman.

The girl could not take her eyes off the young woman’s lips, they were so red. There was also a man dressed in a blue uniform. She stood by the table, waiting to give her uncle the message from her father, trying not to interrupt. After a while her uncle asked what she wanted, so she gave him the message. She then walked into the courtyard, where Rita was with all the others. She understood that the woman with the red lips was coming to teach the children of the village. The schoolroom was to be in one of the rooms of her uncle’s old house.

The day came to go to school. Mother gave her a bag with a jotter and pencils and she was pushed out of the door and told to be good and listen to the teacher. She was nervous and shy. Would the woman with red lips be strict? Would she have a stick? Yes she was, and yes she did. One of her favourite punishments was one strap on each hand for being late for class, and more if late again. Not having homework done earned a child two straps on each hand; more if necessary. For the big boys who said anything about her red lips and laughed, their torture was to kneel on a handful of corn in a corner, facing the wall. If they dared to turn around, five minutes was added to the time.

The girl had seen big boys cry. She had the face of an angel, their teacher, but she was a she-devil with red lips. She was very strict. Every morning there was a hand inspection to see if they were clean and the nails cut; a neck inspection; a head inspection; it went on. Always to greet her with, ‘Buongiorno, signorina maestra.’ They had to endure her presence in the village until the end of July when summer school closed for the year. Then they said, ‘Arrivederci, signorina maestra,’ and hoped never to see her again.

CHAPTER 4

Communion

ALL OF THE children who were eight years old that year had to have their First Holy Communion. The girl knew this already because at home, in a white box, was a beautiful frothy white dress, which her mother had bought in the winter in preparation for this event. The dress was ready, the girl was not.

In preparation for the big day the children had to learn the catechism. To do this they had to go to the convent in Picinisco, where the nuns taught them all they had to know. To know by heart the Ave Maria, Padre Nostro, Credo, and so on. Also the mortal sins that would send them straight to hell. How to confess everything to a priest, and be saved this terrible fate. The nuns put the fear of God into you. The girl would have nightmares, but she thought that it was worth it, thinking of the white dress. On this day, the girl hurried home when school was over; she quickly ate her pasta with tomato sauce, with lots of pecorino cheese on top, and changed into a clean cotton dress.

‘Wash your hands and face,’ called her mother, which she did. Her mother then gave her fifty lira, and off she went. Rita was waiting for her at the turning to her house. Soon other boys and girls who were also going to the convent in Picinisco joined them. The walk to the town would take them about an hour; they had to hurry, the lesson started at two o’clock. It was hot and the afternoon sun was fierce, the road rough and stony, but at least it was all downhill. It would be much harder coming home, but at least then they could take their time and the sun would not be so hot. When they turned the last bend on the road, the town of Picinisco was visible before them and soon they were there.

The convent was close to the edge of the town. The girl, her friend Rita and the others all went in. Sister Teresa was waiting for them and also for children from other villages. The class was almost full with children from Picinisco. A big rough boy made a sound like a sheep, and the town children all laughed. The girl did not know why this was funny. When the class was over, it was then the best part of the day. They would walk down to the piazza, take a huge drink from the ice-cold water of the public fountain and then think what to spend their money on.

For the girl, it was difficult to decide what to have. She wanted everything. First she wanted a small bar of chocolate, then she would see one of the children with a yellow and white ice cream cone, which made her mouth water. The ice cream cost fifty lira; she could have two ice lollies for fifty lira, or three lollipops. She walked about trying to decide. While she walked about, her friend Carmela followed her closely. Every step the girl took, Carmela would take too, until in a fit of anger the girl shouted, ‘Go away, I’m going to have an ice cream,’ and dashed into the shop.

When she walked out, she was licking a rainbowcoloured ice lolly. Carmela was there waiting, with her eyes big and sad. The girl gave her the other ice lolly she’d bought with her fifty lira, which made Carmela jump up and down with joy. They set off for home, trying to make their ice lollies last as long as possible but they were soon gone. A boy had bought a lollipop and was still happily sucking its sweet stickiness, which made her think that perhaps she had made the wrong choice. Still, there was always tomorrow.

It was the feast of Corpus Domini; the girl had been hearing this all week from snatches of conversations she heard from grown-ups. Sister Teresa said that it meant the body of Christ, which they were to receive on their First Holy Communion. When the big day arrived the girl felt so excited; all over the village there was preparation. In her house it was the same.

Everyone’s hair was washed and dried in the sun; a chicken killed and cooked over an open fire. Early in the morning, they stood in the tub and got washed all over, even the boys. They hated this more than anything. All the family were clean and dressed in their best clothes, a basket with their dinner packed. Last of all, to make sure she would not get it dirty, the white box was taken out and the beautiful dress admired by all.

Dress on! A little ring of flowers and a veil put on her head, white socks and dainty white shoes, which hurt her big rough feet, and then, most important of all, a lace-covered bag with a loop for a handle, which she put on her arm.

Off they went in turn, father holding Vincenzo’s hand and looking handsome in his white shirt. Mother with a basket on her head, carrying dinner. Nonna also with a basket on her head. Big brother Fortunato already by the gate, dying to go off with his friends. And last of all the girl, bursting with pure joy.

When they got to the bottom there was Middiuccio, the taxi man. He was there if anyone wanted to be taken to town; ‘So-much per person.’ The girl’s father took the basket off his mother-in-law’s head and put it on the rack on the top of the car and he paid the man.

‘You go in the car, Mamma, the walk is too much for you,’ he said to his mother-in-law.

‘No. I can walk, I’ll go slow,’ she said.

She did not want the money to be wasted on her. But her son-in-law insisted and she was seated in the car along with other people. Family groups soon got together and chatted and laughed as they walked to Picinisco.

The girl was left behind; walking in the long dress was not easy, her shoes were hurting and she soon got a blister. She could see her mother way up in front looking back for her. They were almost at the bend where you could see the town. Her mother shouted to her to hurry. The girl ran to catch up and as she did this, she put her foot in the frill of her dress and it tore. She looked at it and could not believe it, she started to cry bitterly. Her mother looked at her dress: ‘Could you not be careful?’ she said. She then unpinned two or three safety pins, which she always had on her person, and pinned the frill back in place on the dress. ‘There,’ she said. ‘You can’t see it so stop crying.’

Her father looked at the blister and patted her on her head. He took the shoe, put it on a large stone at the side of the road and with another stone bashed the shoe and made it soft. He then took out his handkerchief, tore off a bit of it to make a little padding and put it on the blister. Sock on, shoe on again and happiness returned.

At the convent, the Sisters lined up the children two by two; the girl held on tight to Rita’s hand. Girls at the front, boys at the back. Parents and family also in pairs. They walked in procession through the piazza to the church. Once there, Mass was said and Holy Communion received. This was what the girl, Rita, Carmela and all the rest were waiting for. Free from the Sisters and from family, they made their way through the narrow, cobbled lane back to the piazza. Once there, they were to take a drink from the fountain, to wash down the Body of Christ, which they did. The girl looked around, the piazza was full of people. She went to her Uncle Domenico, Rita’s father, took his hand, kissed it and said, ‘Corpus Domini, Zio.’ Her uncle put his hand on her head to bless her, then he put his hand in his pocket and gave her one hundred lira. She said, ‘Thank you.’ She smiled from ear to ear. She plunged her money into the lace bag and off she went to repeat the action with all her other uncles and aunties and big cousins and all the other zii of the village. To the girl everyone in the village was a zio or zia, an uncle or an aunt.

Late afternoon. Baskets empty. Father still in the tavern drinking. Mother, Nonna, Zia sitting in the shade chatting, watching the small children. Big boys and girls running about playing and grown-up boys and girls laughing together, sitting in groups. Young men sitting with their fidanzate alone, a fare l’amore and all the eight-year-old children counting their money under the old oak tree.

CHAPTER 5

Going to Feed the Dog

BEFORE THE FLOCK of sheep could be moved to the high pastures on the mountains, the snow had to melt. So until that happened, the animals were grazed round about the village. At night they were penned up in the fields, to keep them safe and so they would add manure to the soil, ready to plough up when they were moved up to the mountains.

It was Serafina’s job to take food for the dogs wherever they happened to be. In the house there would be a ‘dog pail’ with leftover pasta and scraps of food, and some bones if they were lucky. The girl would take the pail and also a jam jar with a lid, with a string round the rim to form a handle. It was just getting dark as she set off. As she walked up the road other children, also with pails and jam jars, were walking up the road, also going to feed their dogs. Soon, little groups of children would get together. They would hurry, they had to be there just at the right time. Twilight was best.

‘I’m going to get more than you.’

‘No, you are not.’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘How much do you bet I am going to get more than you?’

And that was more or less the gist of the conversation all the way up.

Just as they got over the brow of the hill, the dogs that were waiting for them bounded down the track to meet them. No, they were not to get their food until they were at their place, beside their flock. The children hurried on, wanting to get their task done. The girl greeted and petted her three dogs, especially Caponero, who was her favourite. She divided the food between the three dogs, making sure they all got a share. By this time it was dark and the illumination had begun. Thousands of fireflies: their lights winking on and off, dancing in the air. The children darting here and there, catching as many as they could and putting them in their jam jars.

Eventually they were tired and made their way home, each with a lantern of light in their hand.

‘Mine is brighter than yours. I bet I have more than you.’

‘You think so? We’ll go and count them.’

The glow from the jars illuminated their steps back down the stony track.

CHAPTER 6

Blind Man’s Buff

AT LAST THE