Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

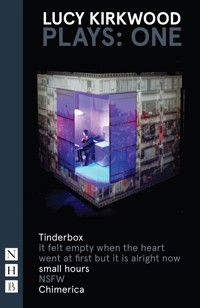

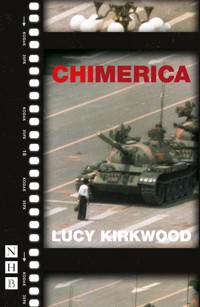

A powerful, provocative play about international relations and the shifting balance of power between East and West. Winner of the Olivier Award for Best New Play (2014), the Evening Standard Best Play Award (2013), the Critics' Circle Best New Play Award (2014), and the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize. Tiananmen Square, 1989. As tanks roll through Beijing and soldiers hammer on his hotel door, Joe – a young American photojournalist – captures a piece of history. New York, 2012. Joe is covering a presidential election, marred by debate over cheap labour and the outsourcing of American jobs to Chinese factories. When a cryptic message is left in a Beijing newspaper, Joe is driven to discover the truth behind the unknown hero he captured on film. Who was he? What happened to him? And could he still be alive? A gripping political examination and an engaging personal drama, Chimerica examines the changing fortunes of two countries whose futures will shape the whole world. Lucy Kirkwood's play Chimerica was first performed at the Almeida Theatre, London, in 2013 before transferring to the Harold Pinter Theatre in the West End.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 159

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Lucy Kirkwood

CHIMERICA

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Characters and Note on Text

Act One

Act Two

Act Three

Act Four

Act Five

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Chimerica was first performed at the Almeida Theatre, London, on 20 May 2013 and transferred to the Harold Pinter Theatre, London, on 6 August 2013. The cast was as follows:

TESSA KENDRICK

Claudie Blakley

JOE SCHOFIELD

Stephen Campbell Moore

LIULI/JENNIFER

Elizabeth Chan

MICHELLE/MARY CHANG/DENG

Vera Chok

DAVID BARKER/PETER ROURKE/PAUL KRAMER/OFFICER HYTE

Karl Collins

FRANK HADLEY/HERB/DRUG DEALER

Trevor Cooper

BARB/DOREEN/MARIA DUBIECKI/KATE/JUDY

Nancy Crane

MEL STANWYCK

Sean Gilder

FENG MEIHUI/MING XIAOLI

Sarah Lam

YOUNG ZHANG LIN/BENNY

Andrew Leung

ZHANG WEI/WANG PENGSI

David K.S. Tse

ZHANG LIN

Benedict Wong

Other parts were played by the company

Director

Lyndsey Turner

Set Design

Es Devlin

Lighting

Tim Lutkin

Sound

Carolyn Downing

Video

Finn Ross

Costume Design

Christina Cunningham

Movement Director

Georgina Lamb

Casting

Julia Horan CDG

Associate Director

James Yeatman

Assistant Director

Ng Choon Ping

Dialect Coach

Michaela Kennen

Mandarin Coach

Bobby Xinyue

Fight Director

Bret Yount

From 2nd September 2013, the following cast changes took place: Wendy Kweh replaced Vera Chok, Liz Sutherland replaced Sarah Lam.

Author’s Note

It is a fact there was a Tank Man. It is a fact that photographs were taken of him. Beyond that, everything that transpires in the play is an imaginative leap.

This is especially the case with the journalist at the centre of the story, who is not based in any way upon a real person, alive or dead. Nor is he an amalgam of many of them. Joe is purely a fictional construct.

One of the reasons I felt able to take this liberty was that the image of the Tank Man we are familiar with in fact exists in a number of forms in common currency. There are at least six recognised versions, the play takes place in an imagined universe in which there are seven. In reality, Jeff Widener’s is the most famous, and I’m very grateful to him for allowing us to use his version in the publicity for the play. Versions of the shot were also taken by Stuart Franklin, Charlie Cole, Arthur Tsang Hin Wah and Terril Jones. Again, Joe is not a cipher for any of these men.

The sources the play draws on are too vast to list here, but special mention must be made of both Don McCullin’s book Unreasonable Behaviour, and When China Rules the World by Martin Jacques, works I found myself returning to again and again over the years, along with two of Susan Sontag’s works, On Photography and Regarding the Pain of Others, and the PSB documentary on the Tank Man. Niall Ferguson coined the term ‘Chimerica’, I read it in his book The Ascent of Money. In writing Ming Xiaoli I found Anchee Min’s recollections in both the Taschen book of Chinese Propaganda posters and her own book, Red Azalea, very useful.

The play took six years to write, and accrued debts to many people in that time. I would like to thank:

Jack Bradley for commissioning me to write the play, and both he and Dawn Walton for their guidance and support in its early incarnations. Ben Power for rescuing the play when it became homeless, and for his dramaturgy and encouragement. Rupert Goold and Robert Icke whose long-term faith in the play is the reason it made it to the stage. Michael Attenborough and Lucy Morrison for embracing the play with such passion, giving it a home at the Almeida, and moving heaven and earth to ensure it had the best possible production. Es Devlin and Chiara Stephenson, whose wonderful designs greatly influenced the ideas and rhythms of the final drafts. Robin Pharaoh, whose crash course in doing business in China was invaluable. Choon Ping and Bobby Xinyue, for their insights into Chinese language and culture, and their work on the Mandarin translations. Stuart Glassborow. Ruru Li. John Bashford and the students of LAMDA. Mel Kenyon, for her tenacious support and incisive notes.

Most of all, Lyndsey Turner, for her rigorous dramaturgy, dedication, hard graft and theatrical imagination. The debt the play and I owe to her cannot be overestimated.

And always, Ed Hime.

L.K.

‘Images transfix. Images anaesthetise.’

Susan Sontag

‘I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend death, to charm motorways, to ingratiate ourselves with birds, to enlist the confidences of madmen.’

J.G. Ballard

Characters

JOE SCHOFIELD

FRANK HADLEY

MEL STANWYCK

TESSA KENDRICK

ZHANG LIN

HERB

BARB

ZHANG WEI

DOREEN

PAUL KRAMER

WAITRESS

YOUNG ZHANG LIN

LIULI

MARIA DUBIECKI

DAVID BARKER

MARY CHANG

WOMAN IN STRIP CLUB

MICHELLE

OFFICER HYTE

DRUG DEALER

JENNIFER LEE

FENG MEIHUI

PENGSI

PENGSI’S WIFE

MING XIAOLI

KATE

DENG

PETER ROURKE

DAWN

JUDY

GUARD

BENNY

NURSE

Also CROWDS, WAITRESS, AIR HOSTESS, SOLDIERS, COUPLE IN RESTAURANT, BARMAID, GIRL IN STRIP CLUB, CAMERAMAN, GUARDS, GALLERY ASSISTANT

Note on Text

A forward slash (/) indicates an overlap in speech.

A dash (–) indicates an abrupt interruption.

Starred dialogue indicates two or more characters speaking simultaneously.

A comma on its own line indicates a beat.

A beat doesn’t always mean a pause but can also denote a shift in thought or energy. When lines are broken by a comma or a line break, it’s generally to convey a breath, a hesitation, a grasping for words. Actors are welcome to ignore this.

Chinese Names

For those who do not know, it’s worth noting that in Chinese names the family or surname comes first, the given name second. Traditionally a generation name, shared by family members of the same generation, prefixes the given name.

So in Wang Pengfei, Wang is his surname, Peng his generation name, which he shares with his brother, and Fei his given name.

Married women do not take their husband’s surname but retain their own.

ACT ONE

Scene One

An image of a man with two shopping bags in a white shirt, standing in front of a line of tanks. It is important he is Chinese... but we cannot see this from the photograph. It is important it was taken by an American... but we cannot know this simply by looking at it. It is a photograph of heroism. It is a photograph of protest. It is a photograph of one country by another country.

Scene Two

5th June, 1989. A hotel room overlooking Tiananmen Square. Split scene, JOE SCHOFIELD (nineteen) is speaking on the landline phone with his editor, FRANK (forty-five), in the newsroom of a New York newspaper. JOE has his camera slung round his neck, watching the square below. It’s around ten a.m. for JOE, eleven p.m. for FRANK.

FRANK. We’re trying to get you on the ten fifteen out of Beijing tomorrow morning, but the airport’s in chaos, the BBC might have a spot on their charter, did you meet Kate Adie yet?

JOE. No, I don’t think so.

FRANK. She’s a doll. Underneath, you sure you’re not hurt?

JOE. I told you, I’m fine.

FRANK. I should never’ve sent you overseas, not so soon, not on your own, a situation like this, you need experience –

JOE. It was a student protest, didn’t know it was gonna turn into a massacre, / did we?

FRANK. You’re not even old enough to drink, chrissakes, what was I – don’t go out again, okay? You stay there, in the hotel, just focus on getting those films back to us.

JOE. You gonna give me a front page, Frank?

FRANK. Yes, Joey, I think three hundred Chinese people being gunned down by their own government warrants a little more than a hundred words on page six, don’t you?

JOE. It was more than that. I was down there, Frank, it was – three hundred, is that what they’re saying? I don’t know, but it was a lot more than –

JOE freezes, looking out of the window.

Oh fuck.

JOE moves to the window, crouches down, watching the man who has walked out.

FRANK. Joe?

JOE. Oh fuck, what is he doing? What is he – Jesus, get out of the road, you stupid –

JOE realises the man’s actions are entirely intentional.

Oh my God.

FRANK. What’s going on there? Joey, talk to me, what are you –

JOE. This guy. He has these... bags, like grocery bags and he... he just walked out in front of the tanks, and he’s just standing there like – I mean, they could just run him right over. But he won’t move, he won’t move, he’s, he’s incredible, I wish you could...

JOE stares, transfixed, breathless. Unconsciously copies the Tank Man’s movements, as if he were holding two shopping bags.

FRANK. Okay, Joe, don’t worry, we’re going to get you / out of –

JOE. Will you just shut up a second?

Frank, this guy, he’s my age.

I think I’m about to watch him get shot.

Silence. JOE picks up his camera. Starts taking pictures.

FRANK. Well, did they do it yet?

JOE. No. Not yet. I’m gonna put down the phone for a second.

JOE lays the receiver down. Takes pictures. Suddenly, banging on the door.

(Sotto.) Shit.

He gently hangs up the phone.

FRANK. Joe? What’s happening –

Lights down on FRANK. JOE quickly winds his camera film to the end. Takes the film out, grabs more used films from his bag, empties dirty underwear out of a plastic bag, puts the films in, ties a tight knot. The phone rings. JOE makes a silent gesture at it, runs off, to the bathroom. The phone stops ringing. The banging ceases. JOE returns without the films. Listening. He goes to the door, puts his ear to it. Puts a new film in his camera, takes shot after shot of the carpet. Shaking with adrenaline. Gathers his camera bag, film. Pulls on his jacket. The phone rings, he dives for it, whispers:

JOE. Frank?

Lights up on FRANK.

FRANK. Jesus, Joey, what are you trying to do to me!

JOE. There were fucking guards outside the door!

FRANK. Well, are they gone? Are you okay?

JOE. Yeah! My heart’s fucking, like, you know?

FRANK. Yeah, what about your films?

JOE. I put them in the toilet cistern –

FRANK. Good boy. You get a good frame of that guy?

JOE. I don’t know, I was just spraying and praying, listen, Frank, I’ll call you back –

FRANK. You will not call me back, you stay on this line, / you hear me!

JOE. Frank, I lost him, I / have to –

FRANK. What d’you mean, you lost him?

JOE. I mean I can’t see him any more, I have to go down there, see if I can –

The door smashes open. A swarm of CHINESE SOLDIERS enter. JOE drops the phone, stands, puts his hands up, backs away.

FRANK. Joe? JOEY!

Lights down on FRANK as the SOLDIERS shout at JOE in Mandarin. JOE remains frozen with his hands up as one SOLDIER steadily aims at him while another grabs his camera, takes the film out, throws the camera against the wall. Punches JOE in the stomach, JOE sinks to the floor. Chaos, violence, shouts in Chinese dialects as we travel forward twenty-three years to...

Scene Three

A plane. JOE is forty-two years old. MEL STANWYCK (forty-five) to his right, TESSA KENDRICK (English) to his left, reading a magazine, knocking back a cocktail. JOE and MEL have beers.

MEL. It’s a seven-star hotel, Joe. Why wouldn’t you want to stay in a seven-star hotel?

JOE. I told you –

MEL. The website says it has an ‘auspicious garden’. An auspicious garden, Joe.

JOE. Yeah but I haven’t seen Zhang Lin / for –

MEL. Sure, right, your friend.

An AIR HOSTESS enters. TESS speaks quietly to her, she takes TESS’s empty glass and goes.

JOE. First time I went back to Beijing, Mel, I was so green you wouldn’t believe it, Zhang Lin asks to meet me, offers to teach me Mandarin, he bought me a suit – I ever tell you that, he bought me a fucking Armani suit! We only have two days, I just want to hang out with him a little. And Frank won’t sign off your expenses, staying in a place like that.

JOE shows MEL some photographs on his phone.

MEL. Ah, I’m gonna haggle them down. I gotta spend two days in a Chinese plastics factory, I want a seven-star mini-bar to fall asleep with. (Re: the photos.) What’s this?

JOE. Somalia.

MEL. You see Greg out there?

JOE. You didn’t hear?

MEL. Dead?

JOE. Only from the waist down. Thirteen-year-old sniper.

MEL. Man, that sucks. I have to find a new racquetball partner.

PILOT (voice-over). Welcome to Flight 9012 from New York JFK to Beijing, approximate landing time in fifteen hours.

MEL hands the phone back. The HOSTESS brings TESS a fresh drink.

MEL (sotto). You know, that’s her third since we sat down?

JOE (looks, shrugs). Complimentary, isn’t it?

MEL. I’m just saying, fifteen hours next to Zelda Fitzgerald, could be a bumpy ride.

TESS looks at them. MEL immediately grins, friendly, raises his beer.

Cheers!

TESS looks back down at her magazine.

TESS. A pansy with hair on his chest.

JOE. Excuse me?

TESS (turns a page). That’s how Zelda Fitzgerald described Hemingway.

Pause. JOE and MEL look at each other.

MEL. Switch seats with me.

JOE. No. (To TESS.) So is this your first time in Beijing?

She looks up from the magazine. Smiles.

TESS. Yes.

She looks back down at the magazine. MEL leans across JOE.

MEL. Business? Pleasure?

TESS (still reading). Are you asking or offering?

MEL. Oh, honey, I’m a recently divorced journalist, I’m no good for either, hey listen, I got a tip for you: don’t eat the chicken.

JOE. Don’t listen to – you can eat the chicken, the chicken / is fine –

MEL. The average piece of Chinese chicken, if you were an athlete, and you ate this chicken, I tell you the steroids they pump into that shit, you would fail a doping test.

JOE. Don’t freak her out.

MEL. True story.

JOE. You speak Mandarin?

MEL. And don’t eat the beef either, ’less you’re sure that’s what it is.

TESS sighs, closes her magazine.

TESS. I can read it a bit.

MEL. They have this paint, okay, they paint the chicken, so it looks like beef, but it ain’t beef. It’s the Lance Armstrong of the poultry world.

JOE. Mel, tell her about the place.

MEL. What place?

JOE. The place, our place, with the bāozi and the asshole waiter.

MEL. Oh my God, yeah, okay, you have to go to this restaurant –

JOE. Write it down for her.

MEL. I’ll write it down for you, you like spicy food?

TESS. I have an asbestos mouth.

,

JOE. So what are you working on out there?

TESSA. I can’t really say.

JOE. No, sure but?

,

JOE and MEL look at her, expectant.

TESS. I categorise people. By, well, anything, purchasing habits, political affiliations, sexual politics. I’m refining the profiling system that... this company uses, we have a Western model but it has to be adapted to the Chinese market.

JOE. So I’m not the special little snowflake my mom always told me I was?

TESS. Sorry to be the one to break it to you. No such thing as an individual.

MEL. Sure, well, maybe not in China, man, I hate this shit.

TESS. Excuse me?

MEL. This ‘if you picked mostly As, you’re a summer-wedding kind of girl!’ scheisse, this insistence people are some... bovine breed, self-selecting themselves into bullshit constellations, tell me what my future is off the back of whether I take sugar or sweetener in my coffee. I know Democrats who play golf with Donald Trump, I’ve met dirt-poor Polish guys who can recite the works of Walt Whitman by heart, millionaires who don’t know how to hold a fucking fish knife, you’re going to a country of one billion people to make some nice boxes to put them in?

TESS stares at him. Drains her drink.

TESS. Okay, I’ve had, like, four of these now, but I’d say, let’s see, I’d say you’re probably a... Group O, with Group B characteristics.

MEL. Group O, Group O, I mean, what a sad, what a really prosaic way to view / your fellow humans!

TESS. Within that, I’d place you as an Anti-Materialist. At some point you were probably Urban Cool with a bit of Bright Young Thing, but I think that ship has sailed, don’t you? You see your work as a career rather than a job, you identify yourself as international rather than national, you have no brand loyalty, your favourite movie is Goodfellas, you believe cannabis should be legalised, that contraception is a woman’s responsibility, that little can be done to change life, that children should eat what they’re given, and that real men don’t cry.

,

I’m sorry, that’s quite a limited, I’d need to ask a few more questions.

JOE. She’s a witch.

MEL. No, okay, because okay a) that thing about the contraception is just plain wrong, because I had a vasectomy, b) Goodfellas isn’t even in my top ten.

TESS. Singin’ in the Rain?

MEL (takes out his book). I want to read now.

TESS. I know, it’s awful, isn’t it? No one likes to know to they’re unremarkable. (To the HOSTESS, her glass.)’Scuse me? When you get a sec? Cheers.

JOE. You gonna do me now?

TESS. I’m not a machine.

PILOT (voice-over). Ladies and gentlemen, we are now approaching take-off. The time is eight fifty-two p.m. local time and the skies are clear.

The plane starts take-off. TESS shuts her eyes.

TESS (sotto). Oh, shit. Oh, shit.

JOE (grins). What’s the matter? It’s only China, coming towards you at five hundred miles an hour.

TESS. Stop it!

JOE. Are you okay?

TESS. No. No, I’m scared we’re going to crash and die.

JOE. Take-off’s the worst. You’ll be okay once we get in the air.

MEL. You know why they tell you to adopt the brace position? So your teeth don’t smash and they can identify your body by your dental records.

JOE. Mel! Leave her alone, she’s scared.

MEL. Aren’t we all, sweetheart. Aren’t we all, listen to this: ‘“I like to kiss very much,” she said. “But I do not do it well.”’

JOE takes TESS’s hand.

JOE. Hi. I’m Joe Schofield.

TESS. Tessa Kendrick.

MEL (looking at the book cover). This guy. This fucking guy.

JOE and TESS look at each other as the plane soars into the sky.

Scene Four

Tiananmen Square. A huge image of Mao. JOE shakes ZHANG LIN’s hand.

JOE. So you haven’t changed one bit.

ZHANG LIN. No, I have two more inches here – (His stomach.) It’s rude of you not to notice.

JOE. That’s the hotel I was staying in, over there. I can see my window –

ZHANG LIN. Yes, yes, I know, you told me. Fifteen up, four across, it’s strange they haven’t renamed it after you yet. Have you eaten?

JOE (makes a face). Factory cafeteria food.

ZHANG LIN. Right, your trip. Did it go well?