Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Dedalus Euro Shorts

- Sprache: Englisch

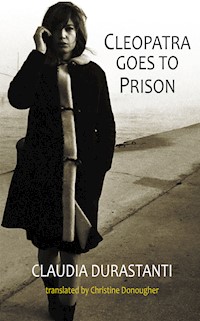

In Caterina, Claudia Durastanti presents us with a Cleopatra for our times - no exotic queen courted by two lovers with the fate of an empire in their hands but a young would-be ballet dancer who now works in as a cleaner in a down-at-heel hotel. This is the Rome of the underclass, of illegal immigrants, gypsies and sex shops where life is a struggle for dysfunctional families and nothing comes easy, except disappointment. Every Thursday Caterina visits her boyfriend Aurelio in Rebibbia prison in Rome, where, following a mysterious tip-off to the police, he is being held in custody under suspicion of pimping the strippers in the nightclub he was running. What would Aurelio say if he knew that she went straight from the prison to meet the policeman who arrested him, and who is now her lover?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 174

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE AUTHOR

Claudia Durastanti is a writer and literary translator based in London. Her critically acclaimed debut novel Un giorno verrò a lanciare sassi alla tua finestra won the Premio Mondello Giovani in 2010. She is the author of four novels. Cleopatra goes to Prison is her first novel to be translated into English.

Claudia is one of the rising stars of Italian fiction.

THE TRANSLATOR

Christine Donougher was born in England in 1954. She read English at Cambridge University and after a career in publishing is now a freelance translator of French and Italian. Her translation of The Book of Nights by Sylvie Germain won the 1992 Scott Moncrieff Translation Prize.

Christine has translated Senso (and other stories) by Camillo Boito, Sparrow (and other stories) by Giovanni Verga and Cleopatra goes to Prison by Claudia Durastanti, for Dedalus from Italian.

Her translations of The Price of Dreams by Margherita Giacobino and Venice Noir by Isabella Panfido from Italian will be published by Dedalus in 2020.

Contents

Title

The Author

The Translator

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Dedalus Celebrating Women’s Literature 2018–2028

Copyright

1

Every Thursday Caterina visits her boyfriend in prison.

Visiting hours are from two to three in the afternoon: usually she takes a bus and walks some of the way to the detention centre, which is signposted – not that she has ever got lost in Rebibbia.

For Caterina the prison smell is that of the flaking iron gates and the aftershave of the clerks who sit beneath calendars with pictures of German Shepherd dogs on them, so she overdoes it with the perfume, hoping Aurelio can get a whiff of it across the space separating them during her visits.

Actually, she also writes short letters to him that arrive at the prison a couple of days later; she sprays the sheets of paper with perfume until they are almost transparent and plasters them with kisses the way she did with photos of the singers she liked when she was in middle school.

Aurelio says his cellmates take the mickey, but if he doesn’t get the letters he is disappointed.

Rebibbia is overcrowded, Caterina can tell from the noise, like that of a junior school canteen. Aurelio has described his room to her – he never calls it a cell – and the guys he shares it with, three drug dealers who speak a consonant-heavy language and consider themselves professionals because they’re not drug users.

At first they cooked together, then Aurelio offered to do it for all of them and his mother began sending him various brands of tinned food. The empty cans are supposed to be confiscated straight after the meals but the inmates use them as ashtrays: in prison everything is metallic, even boredom.

Having checked in, Caterina takes a seat in the area reserved for family visits: Aurelio gives a wan smile as soon as he sees her.

To get to visit her boyfriend she had to have a special interview with the prison governor, a kindly overweight man who explained to her his reluctance to make an exception to the rules.

“It would be unfair to all the other girls in your position, who aren’t spouses, I don’t make any exceptions, not even for the foreigners or the ones with no family.”

It was late afternoon and the governor had apologised for having no lights on in his office, artificial illumination gave him a migraine. Caterina had nodded, continuing to stare at the photo of the President of the Republic hanging behind the desk: the sunspots all over his cheeks and skull made him look as if he were already dead.

“I am an exception: you don’t know how many years I’ve been coming here,” she had replied with a smile.

“Did you have long to wait in line?” asks her boyfriend, collapsing on to the chair.

Caterina shakes her head – Aurelio has stopped thinning his eyebrows, it makes him look more casual, handsome.

“Your lips are cracked, I must remember to bring you a lip salve.”

“There’s no point, I’m always biting them.”

During the visit they talk about how their mothers are, she only gets cross when Aurelio apologises for having ended up in prison.

“Nice lipstick.”

“Someone lent it to me, it’s called Russian Red.”

“And I’ve got a perfume called Black Opium. Doesn’t that make you laugh?” she persists when he remains silent.

“It sounds like a 007 movie… show me your hands.”

Caterina unclenches her hands and spreads her fingers. Her fingertips are peeling, the cleaning chemicals make them blister and go red. Her fingernails, which at one time she used to paint with designs that could win the admiration of the girls behind the bar, are short and suffering from calcium deficiency.

Aurelio was arrested during an operation to clean up areas in Rome known for drug-dealing and prostitution; he and his business partner, Mario, were running a nightclub where, according to the prosecution, the dancers rendered services not included in the price list.

When the place was closed down Caterina was left without a job and now works as a receptionist in a hotel in the heart of Tiburtina.

“You said they didn’t make you do any cleaning.”

“Staff shortage.”

She changed the subject to avoid his clingy sadness.

“Down at the garage someone brought in a Fiat 600 – shades of the past.”

“Are they still around?”

Caterina’s father used to run one of the most respected car repair shops in Pietralata and during a period of expansion he took on two full-time mechanics.

“No one knows why but mechanics are always brothers,” he explained to her the day he hired them: Caterina was eight years old and helped him with the job interviews.

She liked those two men because they turned up wearing blue overalls and sunglasses as if they were supposed to be taking part in a Grand Prix. They had taken over the workshop when her father went back to live in Abruzzo but they left the name unchanged as a mark of respect.

She still drops by sometimes and it amuses them to leave black smudges on her cheeks.

“Your father was mad, he had you driving when you were this small,” they told her recently, indicating knee height for the benefit of a client who wanted only to know what they were going to charge him. “He held you in his arms and let you take the steering wheel.”

Caterina remembered, it was one of the few times her father had frightened her.

Whenever anyone left him with an expensive car – he never had a Porsche, but there had been a lot of saloon cars – he would tell her to get in, then activate the autolift until the car was just below the ceiling and she would be left suspended there to play with the buttons and controls on the dashboard, pretending to be in a spaceship.

She had gone everywhere in that workshop, travelled beyond Jupiter and colonised Mars, taken Barbie to the Moon and seen fireworks created by the blowtorch.

“He had a finely tuned ear for the engine,” the mechanics would say eagerly, smiling, then embarrassment would always set in because their thoughts would turn to where the former owner was now, to the talent he could no longer use. After his arrest for the grooming of a minor, the repair shop motto had become: “Anyone can make a mistake.”

At the age of nineteen Aurelio had a sky-blue Fiat 600, a grown-up Topolino.

They used to listen to electronic music in it, and Caterina liked to go for a spin on the orbital that was closed to traffic after midnight. They would drive along the stretch that swept past a particular row of apartment buildings near Largo Preneste almost going right through their windows, while dust, caught in the street lights, showed up on the dashboard, along with reflections of the green and copper-coloured buildings. A gleam produced by the abrasion of the sky against the flypaper-like strips of cement made her happy.

Then Aurelio passed the Fiat on to his brother, who was ashamed to be seen driving round in it, and the virginity that had been lost on those seats meant nothing to him.

“I’ve started working out again.”

“It shows,” says Caterina, even though it’s not true.

“I do press-ups against the wall like a Buddhist.”

She laughs. “Imagine if you were to become religious while you’re in here. How do you know what Buddhists do?”

“I got a book out of the library. You know what Raoul said to me when I moaned about not being able to use a punchbag? ‘Use me,’ he said. The guy’s crazy.”

Caterina thinks of the times when she lay on her back and whispered the same thing to him, when they were kids and their bones and nerves had hardly finished developing, and being in bed meant trying out whatever their bodies had just discovered they were capable of.

At a certain point during the visit Aurelio asks her who could have framed him.

“Listen, I was thinking last night…”

“You should get some sleep,” Caterina says, touching the dark circles under her eyes. “Otherwise you’ll end up like this.”

“That has nothing to do with sleep, you were born with your eyes like that. It occurred to me last night, it must have been one of the girls, someone who had it in for Mario.”

“Do you need any money? Your mother said she can send you some more.”

Aurelio pulls a face. “You never want to talk about it.”

“They’re things you have to ask him about,” she replies. But Aurelio’s friend and ex-business partner is in Venezuela and doesn’t send postcards.

“I don’t need any money,” he says, ruffling his thick clean hair.

Caterina thinks of him taking a shower, would like to ask if it’s different from taking a shower with his mates at the gym, but is afraid of the possible suggestiveness in her voice.

Aurelio puts his lips to the palm of his hand.

“That’s what I miss,” he says, baring his teeth, and she gives a groan.

“Me too.” Caterina draws closer, grateful not to have to touch his thin chest.

Aurelio had always been slight and the skin could be pulled away from his bones like old tissue paper dug out of the lockers for school holiday decorations, paler than watercolours in a flea market.

The kickboxing competitions he used to take part in had toughened him up but after six months in prison he once again looked like the cocky impoverished kid who had been waiting for her outside school, standing with his arms folded in front of a Fiat 600. He told her she could drive it if she wanted to, but first he complained he had never seen her laugh.

Caterina waves a hand, by way of bemoaning the lack of air; prison is a micro weather station incapable of mitigating the external temperature – in summer you melt, in winter your breath freezes into shards.

“Actually, tell my mother to send me a hundred euros if she can.”

“Your brother’s graduating on the fifteenth, I thought of buying him a watch. What do you think of this one?” she says, pulling out a newspaper cutting showing a pilot watch.

“I don’t like the colour, but go ahead. As long as it doesn’t cost too much.”

“Leave it to me, I’ll sign the card from both of us.”

“A brother who’s an engineer,” says Aurelio, shaking his head.

“You never want to talk about it,” she teases him.

“God knows who he takes after.”

Aurelio stares at the mould in the corners of the room and feels ashamed, the paint on the walls is a lung that does not breathe and does not work.

“I can’t work out who framed me,” he says, continuing to stare at the wall.

“No one framed you, Aurelio, you got yourself into trouble.”

“Don’t call me by my name. It sounds cold-hearted. I may not have a degree but it doesn’t take a genius to realise someone ratted to the police.”

“And what difference would it make knowing who?”

Before opening the nightclub he and his friend had run a video rental store in Torpignattara; it was doing well, then they couldn’t pay the taxes they owed to the State as well as those demanded by the local racketeers. They told everyone the digital revolution was to blame but Caterina knew they said that because they were embarrassed they had not been able to fend for themselves.

“I have to go,” she says, to cauterise the conversation.

Aurelio blows her a kiss and before getting to his feet, adds: “I saw the same watch on the guy who arrested me.”

When she gets her identity card back at the security checkout Caterina remembers the time a prison association organised an open day for families and she brought Aurelio’s nephew to the playground.

While the child was being pushed on the swing by his uncle, she stood chatting with one of his cellmates. They talked about the star-shaped tattoos behind his ear and in the crook of his arm; until then she had only ever seen ones like that on girls.

“It was something that didn’t work out. I want to get a constellation done, but I don’t know whether I’ve got enough skin left,” said the inmate. Caterina thought she was being nice to him but when they were saying goodbye he burst out, “You’re getting out, anyway,” in an abrupt, wounded tone, and she was ashamed at having thought, “I deserve it.”

On the way back she glimpses the mauvish mountain peaks; they are ethereal and distant like figures behind a smokescreen.

Caterina stops off in the parking lot behind an electrical appliances shop, running her fingers through her hair, which is wet from the slight drizzle, and a man inside an unmarked police car hoots his horn. He always picks her up after her prison visits because they don’t have much time to see each other and using public transport would make the situation even worse.

When she gets in the car the policeman kisses her, ruffling her hair which she has just tidied. He asks how Aurelio is doing.

“Same as ever. He seems less depressed, talks rubbish about the future,” she replies, pulling out the newspaper cutting to check whether the watch she wants to buy Aurelio’s brother is the same as the one on his wrist.

The policeman starts the engine and she asks if his shift the night before was long and dangerous.

“Not especially, we took a schizophrenic woman to the Pertini hospital after complaints from neighbours who heard her quarrelling with her mother for stealing her medication. She collapsed in the car, but at A & E they prioritised a woman who had drunk a glass of orange squash and I had to argue with the nurses to get her admitted.”

“Orange squash sends you to A & E?”

“Her son had dissolved his methadone in it because he didn’t like the taste of the methadone on its own.”

“Is she still alive?”

“She is, the schizophrenic isn’t: insulin shock.”

Caterina nods with a bitter taste in her mouth.

“You’re quiet today,” says the policeman, checking on his hair in the rear-view mirror.

“It’s Aurelio. I don’t know what to do about him.” Caterina squints against the light reflecting off the dashboard, her new contact lenses dehydrate her eyes.

“You don’t have to do anything,” he says, stroking her bare leg – she always wears a short skirt when she goes to the prison even if Aurelio can’t see anything from where he is seated.

“He keeps wondering who it was, he doesn’t understand it was a random inspection you carried out.”

“If you attract a certain type of clientele, people talk. Try and tell him that next time.” The policeman parks close to a cast-iron cannon dedicated to the war dead – this is the first time he has brought her to his place.

He does not like living in this area but his salary does not yet allow him to move to a residential neighbourhood; his grandfather left him the apartment and he has done no more than repaint it.

Thanks to his working hours, he does not have to spend too much time among these low square-roofed houses, where the plastic awnings the neighbours have put over their front doors look like faded strips of red liquorice, and Sunday morning lie-ins are disturbed by the rumble of the carwash in his apartment building.

“I’ve never told you anything, I’ve never helped anyone with their inquiries,” says Caterina, walking beside him.

Before crossing the road she points to a supermarket covered with stickers and Chinese characters. “Aurelio and Mario had a video rental store right there.”

“That’s funny, last month we found a girl walled up alive on the floor above. Dodgy massages, money laundering, I’m not allowed to talk about it.”

Caterina turns to see if he is joking, but the policeman is staring at the pavement.

“However, you did tell me something about the nightclub world. Your boyfriend is surrounded by talkers,” he says, taking her by the arm – he is not as yet capable of holding her hand when they are out for a walk. At the crossing, she stops at the traffic lights, the smell of petrol fumes makes her gorge rise.

“That’s not true, don’t say it even as a joke. I can’t bear it, I’ve never told you anything.”

“What flavour ice cream do you want?” asks the policeman as they cross, and Caterina replies that on Thursdays she is never hungry.

In the late afternoon they make love in the bath; the policeman sucks her steam-softened wrists and Caterina’s blood runs hot and frantic like the ink spilled from smashed Bic biros. “I can’t believe you’ve never done it before. You’re thirty,” he says to her, before lying her on her stomach. When he lifts her pelvis Caterina smiles and replies, “I’m a dancer not an animal.”

Later, as they drink water in the living room under the ceiling spotlights, she gets the ammoniac aftertaste of betrayal – which is what prevents her from sleeping and makes her eyes red and watery, like a rabbit’s.

2

The circus has had to park on the tarmac because there is no space in the park, as the local authority preferred to give the licence to an Indian community celebrating some strange festival.

Every afternoon I go out on the balcony and see the children stuffing their mouths with sugar before running around with plastic flags; the mothers stand about, eating and adjusting their purple and golden garments – from their faces it looks more like a funeral than a festival.

In the evening I have to close the window despite the heat because I don’t know how else to protect myself from the noise, but the music gets in under the glass anyway; I think I know some of the songs by heart now, although I don’t know anyone Indian, who could tell me whether I’m getting the words wrong.

Aurelio asked if I wanted to go and see the snakes and I said yes, because the funfair rides are close to the circus and I want to say hello to my friend who sets them up.

Aurelio doesn’t know him, we’ve been dating for a week and we don’t talk much about the past.

While I am having a shower before going out my mother comes into the bathroom and starts giving me a summary of what’s been happening in a TV soap; I ask her if she could put out her cigarette because the bathroom is the only room where I can get away from that smell.

“Our life would have been much easier if you’d started smoking as well,” she says, breaking off the tip of the Marlboro, throwing it into her cup, and keeping the rest.

“And who would have paid for them?” I ask from behind the curtain that I wash with bleach to get rid of the limescale.

I hear her put the toilet seat down, to sit on it, while I wait for a bit to soak in a coconut conditioner that according to the hairdresser will revive my hair in ways I cannot even imagine, and as a matter of fact after a month I still can’t.