Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

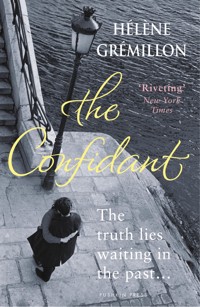

I got a letter one day, a long letter that wasn't signed. Camille reads this narration of events from pre-war France, certain that it has been sent to her by mistake. Then more letters start to arrive - They tell of a friendship struck up between a young village girl, Annie, and Madame M, a bourgeois lady. To begin with the women simply share a love of art, but when Annie offers to carry a child for her infertile friend, their lives become intimately entwined. The child is born on the eve of the German invasion of France, and the repercussions of her birth are still felt decades later. This stunning debut novel, in the vein of Irène Némirovsky's 'Suite Française', is a gripping study of the destruction unleashed, when human desires for love and motherhood turn to obsession.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 337

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The Confidant

‘A riveting story that is both thriller and historical tale … This first-time novelist has produced a highly mature text that displays an extraordinary mastery of narrative, and a feel for suspense that is worthy of the best films. And above all, her characters are endowed with psychological depth’ Le Figaro Littéraire

‘Hélène Grémillon takes us into the heart of a family secret: unspoken love, hidden hatred and revenge with dire consequences. A novel written in two time frames, with two voices, which rewards us twice over, by going straight to the heart’ Elle

‘The Confidant is a must read for anyone who loves intrigue. It will keep you guessing until the very last page – beautifully written, original and thoroughly engaging.’ Sandra Smith, translator of Suite Française

‘An impressive blend of historical precision, high suspense and sharp-sighted psychological truths … Grémillon has so much empathy for all her characters and at the same time such an unflinching eye. A gorgeous, captivating novel with brilliant storytelling. I finished it and wanted to start reading it all over again.’ Amanda Hodgkinson, author of 22 Britannia Road

‘Grémillon’s debut novel, set against the backdrop of WWII Paris, cleverly weaves two stories together to create a truly compelling read.’ Grazia

‘A complex plot, crystalline writing – Hélène Grémillon’s talent explodes in this first novel, as much in her historical precision as in the suspense that lasts until the final paragraph.’ Le Nouvel Observateur

‘A novel about the complicity between history with a small h – the characters’ stories – and History with a capital H. As in Bernard Schlink’s The Reader, nothing is more moving than to witness characters as castaways shipwrecked by History.’ BSC World News

‘Sensitively written, it is a suspenseful, absorbing tale about the power of history and how it plays on the present. A stylish novel with vivid characters and a quirky denouement.’ Herald on Sunday (NZ)

THE CONFIDANT

HÉLÈNE GRÉMILLON

TRANSLATED BY ALISON ANDERSON

For Julien

The past wears its armoured breastplate and blocks its ears with the wind’s cotton wool. No one will ever be able to tear its secret away.

The Premonition Federico García Lorca

Contents

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Paris, 1975

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Paris, 1975

I got a letter one day, a long letter that wasn’t signed. This was quite an event, because I’ve never received much mail in my life. My letter box had never done anything more than inform me that the-sea-was-warm or that the-snow-was-good, so I didn’t open it very often. Once a week, maybe twice in a gloomy week, when I hoped that a letter would change my life completely and utterly, like a telephone call can, or a trip on the métro, or closing my eyes and counting to ten before opening them again.

And then my mother died. And that was plenty, as far as changing my life went: your mother’s death, you can’t get much better than that.

I had never read any letters of condolence before. When my father died, my mother had spared me such funereal reading. All she did was show me the invitation to the awards ceremony for his medal. I can still remember that bloody ceremony, it was only three days after my thirteenth birthday. There was a tall bloke shaking my hand, a smile on his face, but it was actually a grimace. His face was lopsided and when he spoke it was even worse.

‘It is infinitely deplorable that death was the outcome of such an act of bravery. Mademoiselle, your father was a courageous man.’

‘Is that what you say to all your war orphans? You think a feeling of pride will distract them from their sorrow? That’s very charitable of you, but forget it, I don’t feel sorrowful. And besides, my father was not a courageous man. Even the huge quantity of alcohol he consumed every day couldn’t help him. So let’s just say you’ve got the wrong man and leave it at that.’

‘This may surprise you, Mademoiselle Werner, but I insist it is Sergeant Werner – your father – that I am talking about. He volunteered to lead the way, the field was mined and he knew it. Whether you like it or not, your father distinguished himself and you must accept this medal.’

‘My father did not “distinguish himself”, you stupid man with your lopsided face. He committed suicide and you have to tell my mother he did. I don’t want to be the only one who knows, I want to be able to talk about it with her and with Pierre, too. You can’t keep a father’s suicide a secret.’

I often dream up conversations for myself, where I say what I am thinking; it’s too late but it makes me feel better. In actual fact, I didn’t go to the ceremony in honour of the veterans of the war in Indochina, and in actual fact I only ever said it once, other than in my own head – that my father had committed suicide – and that was to my mother, one Saturday, in the kitchen.

*

Saturday was the day we had chips and I was helping my mother peel the potatoes. It used to be Papa who helped her. He liked peeling and I liked to watch him. He was no more talkative when he was peeling than when he wasn’t peeling, but at least there was a sound coming from him and that felt good. You know I love you, Camille. I always had the same words accompany every scrape of the knife as it sliced: you know I love you, Camille.

But that Saturday other words accompanied the scrape of my knife: ‘Papa committed suicide, you knew that didn’t you, Maman? That Papa committed suicide?’ The frying pan fell, shattering the floor tiles, and the oil splattered onto my mother’s rigid legs. Even though I cleaned frenetically for several days, our feet continued to stick, causing my words to grate in our ears: ‘Papa committed suicide, you knew that didn’t you, Maman? That Papa committed suicide?’ To keep from hearing them, Pierre and I spoke more loudly – perhaps to mask Maman’s silence as well, for she had hardly spoken at all since that Saturday.

The kitchen tiles are still broken. I was reminded last week while I was showing Maman’s house to a couple who were interested. And if they turn into a buying couple, every time that interested couple looks at the big crack in the floor they will lament the prior owner’s carelessness. The tiles will be the first thing they’ll have to renovate, and they’ll be pleased to get down to work. At least my horrible outburst will have been good for something. They absolutely must buy the house – whether it’s this couple or another one makes no difference to me, but someone must buy it. I don’t want it and neither does Pierre: a place where the slightest memory reminds you of the dead is not a place where you can live.

When she came back from the ceremony for Papa, Maman showed me the medal. She told me that the guy who had given it to her had a lopsided face and she tried to imitate him, tried to laugh. Ever since Papa died, that was all she could do: try. Then she gave me the medal, squeezing my hands very tight and telling me that it was mine by right, and she began to cry; that was something she could do without trying. Her tears fell on my hands, but I pulled away from her abruptly; I could not stand to feel my mother’s pain in my body.

When I opened the first letters of condolence, my tears falling on my hands reminded me of Maman’s, and I let them fall, to see where they might have gone, the tears of this woman I had loved so much. I knew what the letters would have to say: that Maman had been an extraordinary woman, that the loss of a loved one is a terrible thing, that nothing is more wrenching than bereavement, et cetera, et cetera, so I didn’t need to read them. Every evening I divided the envelopes into two piles: on the right those with the sender’s name on the envelope, and on the left those without. And all I did was open the pile on the left and jump immediately to the signature to see who had written to me and who I would have to thank. In the end I didn’t thank a lot of people and nobody held it against me. Death forgives such lapses of courtesy.

*

The first letter from Louis was in the pile on the left. The envelope caught my attention even before I opened it: it was much thicker and heavier than the others. It was not the usual format for a letter of condolence.

It was handwritten, several pages long, unsigned.

Annie has always been a part of my life. I was two years old, just a few days short of my second birthday, when she was born. We lived in the same village – N. – and I often happened upon her when I wasn’t looking for her – at school, out on walks, at church.

Mass was a terrible ordeal, for I invariably had to put up with the same routine, stuck between my father and mother. The pews one occupied at church reflected one’s temperament: fraternal company for the gentler children among us, parental for the more recalcitrant. In this seating plan, which the entire village adopted by tacit consent, Annie was an exception, poor girl, for she was an only child, and I say ‘poor girl’ for she complained of it all the time. Her parents were already old when she came along, and her birth was hailed as such a miracle that not a day went by without them saying ‘all three of us’, in that way, whenever the opportunity arose, while Annie was sorry not to hear ‘all four or five or six of us’…With every mass this unavoidable situation seemed to become all the more trying for her as she sat alone in her pew.

As for myself, while nowadays I hold boredom to be the best breeding ground for the imagination, in those days I had ordained that the best breeding ground for boredom was mass. I would never have thought that anything could happen to me at mass. Until that Sunday.

From the moment of the opening hymns a deep malaise came over me. Everything seemed off-balance – the altar, the organ, Christ on his cross.

‘Stop breathing that way, Louis, everyone can hear you!’

My mother’s scolding, added to the malaise that would not leave me, called to mind a phrase I had tucked away, words my father had murmured to her one evening: ‘Old Fantin has breathed his last.’

My father was a doctor and he knew every expression there was for announcing a person’s death. He used them one after the other, whispering into my mother’s ear. But like all children I had a gift for picking up on what adults murmured to each other, and I had heard them all: ‘close one’s umbrella’, ‘die in his boots’, ‘give up the ghost’, ‘die a beautiful death’ – I liked that last one, I imagined it did not hurt as much.

And what if I were dying?

After all, one never knows what dying is about until one dies for good.

And what if my next breath proved to be my last? Terrified, I held my breath and turned to the statue of Saint Roch, imploring him; he had cured the lepers, so surely he could save me.

*

It was out of the question for me to return to mass on the following Sunday; this time death would not pass me by, I was convinced of that. But when I found myself in the pew I occupied every week with my family, the malaise I was dreading did not descend upon me. On the contrary, I was overcome by a particularly sweet feeling, and I rediscovered with pleasure the smell of wood that was so peculiar to that church: everything was as it should be. My gaze was back where it belonged, focused on Annie, although all I could see of her was her hair.

Suddenly I understood that it was her absence the previous week that had thrown me into such horrible turmoil. She must have been lying down at home, with a facecloth on her forehead to calm her spasms, or she had been painting, protected from any abrupt movement. Annie was subject to violent fits of asthma, and we all envied her because this meant she was exempt from the activities we found unpleasant.

Her figure, still shaken by a slight cough, restored fullness and coherence to everything around me. She began to sing. She was not naturally joyful and I was always surprised to see her become animated and start singing so wholeheartedly the moment the organ sounded. I did not yet know that song was like laughter, and one could invest it with anything, even melancholy.

Most people fall in love with a person upon seeing them; in my case, love caught me off guard. Annie was not with me when she moved into my life. It was the year I turned twelve – she was two years younger, two years minus a few days. I began to love her the way a child does, that is, in the presence of other people. The thought of being alone with her did not occur to me, and I was not yet old enough for conversation. I loved her for love’s sake, not in order to be loved. The mere fact of walking past Annie was enough to fill me with joy. I stole her ribbons so that she would run after me and snatch them, brusquely, from my hands before turning on her heels, brusquely. There is nothing more brusque than a little girl in a fit of pique. It was those scraps of cloth that she rearranged clumsily in her hair that made me think, for the first time, of the dolls in the shop.

My mother owned the village haberdashery. After school we both went there: I to join my mother and Annie to join hers, for Annie’s mother spent half her life there, the half she did not spend sewing. One day, as Annie was walking past the shelf with the dolls I was suddenly struck by the resemblance. It was not only the ribbons; she had the same fierce white and fragile complexion as the dolls. At that point my youthful powers of reasoning got the better of me, and I realised that I had never seen any of her skin other than what her neck, face, feet, and hands could offer. Exactly like the porcelain dolls! Sometimes when I went through the waiting room at my father’s surgery I would see Annie there. She always came alone to her consultations with my father, and she would sit there, so small in the black chair. When her asthma overwhelmed her she resembled the dolls more than ever, her coughing fit spreading like rouge over her cheeks.

But of course my father would never tell me that she had the body of a rag doll, even if I asked him about her. ‘Professional secret,’ he would reply, tapping me on the head before tapping Maman on the backside. And she would smile back at him with that smile I found so embarrassing.

As any resemblance is reciprocal, the porcelain dolls made me think of Annie. So I stole them. But once I was in the refuge of my room, I was inevitably struck by the fact that their hair was either too curly or too straight, their eyes too round or too green, and they never had Annie’s long lashes that she curled with her index finger when she was thinking. These dolls were not meant to resemble anyone in particular, but I held it against them. So I went to the lake and tied a stone to their feet, then watched without sorrow as they sank effortlessly, my thoughts already on the new doll I would take and who would bear a greater resemblance to Annie, or so I hoped.

The lake was deep, and the spots where one could bathe without danger were rare indeed.

That year at the centre of the world there was me, and there was Annie. All around us lots of things were happening that I couldn’t care less about. In Germany, Hitler had become chancellor of the Reich, and the Nazi party exercised single party rule. Brecht and Einstein had fled while Dachau was being built. It is the naïve pretension of childhood to think one can be sheltered from history.

I skimmed the letter, and had to go back and reread entire sentences. Since Maman’s death I had no longer been able to concentrate on what I was reading: a manuscript I would normally have finished in one night now required several days.

It had to be a mistake. I did not know anyone called Louis or Annie. I turned the envelope over, but it was definitely my name and address. Someone else with the same surname, in all likelihood. The man called Louis would realise soon enough that he had made a mistake. I didn’t dwell on it any longer and finished opening the other letters, which really were letters of condolence.

Like any good concierge, Madame Merleau had not been fooled by this flood of mail, and she handed me a little note: if need be, I must not hesitate, she was there.

I would miss Madame Merleau, more than I would miss my flat. The one I was moving into might be bigger, but I would never find a concierge as nice as she was. I didn’t want to go through with this move. Couldn’t I just stay in bed, here in this studio which scarcely a week ago I could hardly tolerate? I did not know where I would find the energy to drag all my stuff over to that place, but I no longer had the choice: I needed an extra room now. And besides, the papers had been signed and the deposit had been made; three months from now someone would be here in my place and I would be there in someone else’s place, and they in turn would be in the place of…and so on. Over the telephone the man from the removal company had assured me it was true: if you followed every link of that chain, you invariably came back to yourself. I hung up. I couldn’t care less about coming back to myself, all I wanted was to come back to my mother. Maman would have been happy to know I was moving; she had never liked this apartment, she only came here once. I never understood why, but that’s the way she was, she took things to extremes sometimes.

Still, I had to let Madame Merleau know that I was moving out and thank her for her note.

‘Oh, don’t mention it, it’s the least I can do.’

Whenever anything happens, a concierge already knows about it. She was clearly sorry for me, and she invited me to come in for a few minutes if I felt like talking. I didn’t feel like talking, but I went in for a few minutes all the same. As a rule, we had always chatted at the window, never inside her loge. If I had not already known that this was a difficult moment for Madame Merleau, her invitation alone would have sufficed to make me understand. After she had closed the curtain behind us, she switched off the television and apologised.

‘The moment I open that bloody window, people look inside. They can’t help it. I don’t think they’re really curious, but it’s unpleasant. Whereas when the television is on they hardly look at me. Fortunately the screen is enough to distract them. I couldn’t stand to hear it blaring in my ears all day long.’

I felt ashamed and she realised.

‘Forgive me, I wasn’t saying that about you. You don’t bother me.’

What a relief! I was off the hook – not part of the average mediocrity.

‘With you it’s not the same. You’re nearsighted.’

I was startled.

‘How did you know?’

‘I know because nearsighted people have a particular way of looking. They always look at you more insistently. Because their eyes are not distracted by anything else.’

I was stunned. It was like being handicapped, with everyone pointing at you. Was it that obvious? Madame Merleau burst out laughing: ‘I’m having you on. You told me yourself. Don’t you remember, the day I told you about my fingers, you said it was sort of the same thing with your eyes. “Life is all about being dependent on your body’s every little whim,” that’s what you said. I thought your explanation was terrifying and I remembered it, the way I remember everything I find terrifying. You have to always remember what you say and who you say it to, otherwise some day it might come back to haunt you.’

She leaned over to pour some coffee, but just then her hand began to shake with a violent tremor and the boiling liquid spilled onto my shoulder. I blew on the burn to cool it but above all so I would not have to look at Madame Merleau. I was terribly embarrassed to have witnessed her infirmity.

Before she became the concierge, Madame Merleau had been a tenant in the building. She arrived shortly after I did, two or three months, I think. The sound of her piano resounded throughout the building, but no one complained, her students were committed and the lessons never turned into an ordeal. On the contrary, the ongoing concert was quite pleasant. But as the weeks went by the piano was heard less and less, and I assumed that her students were getting married. Married people didn’t take lessons any longer. Then the piano stopped altogether, and one day it was Madame Merleau herself who opened the window to the loge as I went by. She had acute rheumatism in her joints. The doctors conceded that it was an early onset, and that this sometimes happened, in particular with professional musicians, as their joints tired more quickly, by virtue of being called upon to play. They did not know exactly when, but eventually she would lose both the control and the mobility of her fingers; she was not to worry, she would still be able to use her hands for everyday things – eating, washing, brushing her hair, doing the housework – but she would no longer be able to use them for her profession, or at least not in all the subtle ways she had known up to now. In a matter of weeks she would lose the precious mastery that her hands had taken so many years to acquire.

She was completely devastated by the news. How would she live? The money from her lessons was her only source of income, she had no savings, and no one on whom she could rely, even for the time it would take to find her bearings. No parents, no children.

Then she heard that the concierge of the building was leaving. For several weeks people told her that she was the wrong age and didn’t have the skills required for such a position. But she decided to submit her application to the owner, who agreed to give her the position. She bade farewell to her piano. She reasoned that an unfulfilled passion was too burdensome, and that one must know how to leave it behind in order to let another passion take its place. Why not astrology, for example? It would go well with her new profession as concierge, the know-all, gossipy side. And it would enable her to forestall her fits of clumsiness. If she had known she was going to spill the coffee today, she would not have offered me any. She smiled.

‘You cannot go to work with your jumper in such a state. Go back upstairs and fetch another one. I’ll take this one to the dry cleaner’s, it will be ready this evening. I am really sorry.’

‘Please don’t bother, it’s fine like this.’

‘I insist.’

I wasn’t one to insist so I went back upstairs. She could not be expected to know that I didn’t have a single clean jumper in my wardrobe, that in fact I had nothing at all in my wardrobe, that all my clothes were on the floor and I walked all over them without caring. Just like Papa, I thought to myself, the moment I felt a bit of cloth underfoot: ‘Pick them up, pick them up, please, you always pick up Papa’s clothes, pick up mine, too!’ But Maman did not pick them up. I managed to find one jacket that did not stink of cigarettes – it really was time to quit smoking.

Madame Merleau waved goodbye to me from the window. As the curtain fluttered closed I thought of how the last survivor of a family never receives any letters of condolence. With all that, I had completely forgotten to tell her that I was moving, but at least we didn’t talk about Maman. Madame Merleau did not seem to be any more at ease in the realm of mourning than I was; so much the better.

That evening, when I came home, I was surprised not to find any letters in my box: the end of the letters of condolence already. Meagre takings, Maman. When I opened the door to my flat the smell of cleaning seized me by the throat: everything had been put away, the dishes I had not had the strength to wash for several days were now done, my laundry had been washed and ironed, and my sheets had been changed. A blinking light came from the door to the sitting room. Perhaps Maman’s white ghost would smile at me the moment I entered the room.

The television had been left on, without the sound. Madame Merleau. Hanging in plain view from the wardrobe handle was my jumper, and she had left my letters on the table. A mixture of disappointment and gratitude overwhelmed me, and no doubt tears would have taken over, had my attention not been drawn to a letter that was bigger and thicker than the others. I opened it. Just as I thought. Him again. Louis was continuing his story where he had left off.

Annie and I attended the same school. Our institution was in a single building, but despite this apparent permissiveness, honour was intact, and the rules governing the division of the sexes were well and truly respected. The girls were on the ground floor, and the boys were upstairs. As a result of this chaste state of affairs, several days could drag by without my catching a glimpse of Annie, during which I was reduced simply to imagining her curling her eyelashes with her studious index finger, or to trying to guess which footsteps were hers when pupils went up to the blackboard, then moments of sudden delight when I recognised her cough.

I hated those two storeys. I hated them all the more given the fact that the arrangement had not always been like this. In the old days the girls used to be upstairs. My cousin Georges, for example, could still see the girls’ panties as they came down the stairs four at a time – white ones, pink ones, blue ones, he filled his head with them as he gazed through the gaps in the stairway, all the better to admire the rainbow unfurling miraculously before him come rain or shine. But there we are; as is often the case, my generation had been sacrificed because of the idiocy of the previous one. Their lecherous ogling had not gone unobserved by Mademoiselle E., the headmistress, so the boys ended up on the upper floor, and without our shoes, which we had to take off so as not to make any noise. There we were for the girls to spy on in turn and make fun of the holes in our socks as we came down the stairs, shoving each other savagely to be the first out of doors. Because whoever was first out of doors was the winner; of course there was no reward, but at that age, the challenge itself was enough, particularly when the girls were watching. The number of bruises and falls that ensued must have worried Mademoiselle E., but she never went back on her decision, and morality continued to prevail over safety.

Until the blessed day when this despised arrangement ended up working in my favour. And why not, I too wanted to be the first out the door. It was a completely pointless resolution of mine, which landed me with a fractured shinbone and kept me immobilised for several weeks. But all was not lost and the point was revealed soon enough: the very next evening, Annie came to the door of my room. Given that she joined her mother at the haberdashery almost every evening anyway, Annie had volunteered to bring me my homework. She stood up, braving the sarcasm of the classroom and the idiotic guffaws that would designate her as the very girl I wanted her to be, ‘my sweetheart’. She left me my lessons every day. Never before had I seen so much of her, and there I was, dazed, my leg stiff along with all the rest. I had to keep her there, longer than those few minutes she spent not knowing where to sit, and I not knowing where to look. We had both reached the age when our bodies had become important: hers was on display, and I could fantasise about it.

I was afraid that she might grow weary of this dull mission, that she might delegate someone else to perform it in her place. So under the pretext of an ordinary homework assignment, I asked my mother to borrow some books about painting from the library, and as I waited impatiently for Annie to make her appearance – fearing all the while that someone else would come – I immersed myself in reading. I hoped that by speaking to her of her passion I might, in turn, become an object of passion myself.

And that is how women painters became my new porcelain dolls, my new go-betweens in a love story for which I had not yet found the words. I told her about their lives in the most minute detail, and Annie listened attentively, without ever seeming surprised that I knew so much. I had succeeded: our minutes of conversation turned into hours.

That year, Tina Rossi sang ‘Marinella’, which I chanted alone in my room, as I staggered round on my broken leg. ‘Annieeeella!’ We were not the only ones putting on a show. In Germany, Hitler launched the Volkswagen ‘Beetle’ and violated the military clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. But as he could not be in two places at once, at the Berlin Olympic Games a black American was awarded four gold medals. In Spain, the civil war broke out, and at home in France, the Popular Front won the elections hands down.

I couldn’t believe it, the correspondent still had it wrong. I had to find this guy and tell him he had the wrong addressee. But I had no way of tracing him, I couldn’t send his letters back to him, there was no return address on the envelope. There wasn’t even a signature; he did mention this ‘Louis’, granted, but ‘Louis’ who?

And were they even letters? They hardly looked like letters: no ‘Mademoiselle’ or ‘Dear Camille’ to start with. No indication of place or date on the letterhead. And to top it all off, the ‘Louis’ in question didn’t even seem to be addressing anyone in particular.

I was startled by the sudden ringing of the phone. Who could be calling me in the middle of the night?

It was Pierre.

I hardly recognised my brother behind that faint, reedy voice asking me whether I realised we were now orphans? That word swept everything away. He couldn’t sleep. I’d be right over. Could I stop and get him a pack of cigarettes? Of course.

This was not the time to lecture him. Besides, I felt like smoking, too, and I had thrown out what was to have been my last pack that very morning.

It is not other people who inflict the worst disappointments, but the shock between reality and the extravagance of our imagination.

Annie and I always walked together from school to the haberdashery. We never left at the same time, but the distance between us gradually shrank along the way. Whoever was walking in front would slow down, while the one behind picked up speed, until the two of us were walking side by side.

But years later, when we met again – on 4 October 1943, in Paris – Annie laughed and said I was the one who played both parts: either I caught up with her, or I let her catch up with me, but as far as she was concerned she swore she had never adjusted her speed. I did not seek to deny it; it was true that I wouldn’t have missed those walks with her for the world. In my mind, I called them our ‘lovers’ strolls’ – words often help to rearrange the nature of things. It was true, too, that I had long hoped for something between us, but things had turned out differently. She must have been married by then; at twenty, that was normal – I had deliberately aged her a year or two, to hurt her feelings a bit. I had seen the wedding ring on her finger. I was pretending. I was playing the part of the man who does not chase after women, who no longer hopes. The man whom one need not fear. As a child I had never used any tricks to secure her affections, but on that 4 October 1943, with my eyes glued to the ground to avoid her gaze, I could hear myself saying the exact opposite of what I was thinking. I was obligingly opening the way for her to tell me whatever she liked, with no regard for the past. What of her life, today? Was she happy?

Oddly enough, Annie replied with a confession.

‘I must tell you, Louis, that you have always been the first. The first to kiss me, the first to caress my cheek, my breasts, the first who knew that there were days when I wore nothing under my skirt.’

Annie reminded me of all those first times; she remembered everything better than I did.

‘Why did you never tell me this?’

She looked up at me.

‘What’s the point in telling a man that he was the first? Do you tell the twelfth man that he was the twelfth? Or the last that he was the last?’

I did not know what to say.

Did she hope, by pouring out all her memories, that I would forgive her for everything that never happened between us? The truth is, she began to change when she first started spending time with that Madame M.

Annie stood up abruptly, as if suddenly embarrassed to be near me. She offered me a chicory coffee, apologising that, because of the rationing, she no longer had any real coffee, or any sugar. She was nervous, opening all the cupboard doors as if she didn’t really know what she was doing. Her apartment was very small. I watched her bare feet moving about her few square metres of living space. Her kitchen – a sink and a hot plate – was next to her bed, fortunately, for had she so much as left the room I might have doubted her very presence. I hadn’t seen her for three years. For three years I’d had no news of her at all. At no time did I suspect she might be living in Paris like me. I looked at her fingernails, her peeling red varnish; in the village she never used to wear any. Seeing her again like this: it seemed too good to be true. Outside it was pitch black. I was suddenly overwhelmed by desire for her. She handed me a steaming hot cup.

‘So, do you remember Monsieur and Madame M.?’

How could she ask me such a thing?

I rang the post office first thing next morning. The postmark indicated that the three letters had been mailed from the fifteenth arrondissement. Perhaps there was a number in the postmark that I had missed and that would indicate precisely which letter box had been used. I could go and put up a poster asking the famous Louis to contact me.

But their reply was unequivocal: there was no way to know. I couldn’t exactly go putting posters on every letter box in the fifteenth arrondissement, I had plenty of other things to do, never mind the number of weirdos who would call me for all sorts of reasons, but never about the letters.

The letters had to mean something to someone, and somewhere in Paris there must have been another Camille Werner who was expecting them. She was the one I had to find. Sure at last that I had hit on the solution, I embarked on a search for all the homonyms. Shit! I would never have thought there could be so many Werners in Paris. I really have to stop swearing like this all the time, Pierre is right: it’s not very feminine, it’s hardly the way to make Nicolas come back to you. Shut up, Pierre. Don’t talk to me about him. I don’t go talking about the girls you sleep with, do I?

I called every Werner in the telephone directory to ask them 1) whether there was anyone by the name of Camille in their family, 2) did they by chance know anyone by the name of Annie? I met with a few polite, reserved ‘no’s. But some of the other reactions were quite surprising. There was one woman who hung up on me, terrified to hear an unfamiliar voice. There was one who didn’t know any Annies, but she knew an Anna, was I sure I wasn’t looking for an Anna? And then there was one who had scarcely had time to pick up the phone before her husband started shouting at her to hang up, telling her it was robbers, that’s what they always do in the holidays, to find out whether anyone was at home.

But no sign anywhere of another Camille Werner.

Tough luck, Louis. He would have to go on writing to me for no good reason.

By Tuesday a new envelope was waiting for me, just as thick, but all alone now in my letter box. The same stationery, a very smooth parchment; the same handwriting – a distinctive capital ‘R’, the same size as a lowercase letter, slipping effortlessly into the heart of a word – and the same smoky scent, a perfume that reminded me of something or someone, but I couldn’t figure out who or what.

Monsieur and Madame M. were a very wealthy young couple. Both sets of their parents had flawlessly fulfilled their duty as overzealous forebears by dying unusually young and unusually rich. Their last will and testament was dripping with real estate, but the M. couple chose to settle in L’Escalier, to our great misfortune.