Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

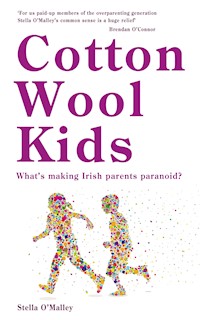

What has happened to Irish childhood? Parents are keeping their children indoors for fear of predators lurking around every corner and children are spending their days in front of screens or in supervised activities, over-controlled and growing steadily fatter and more unhappy. But it doesn't have to be like this. Commercial interests ensure parents feel anxious and filled with fear simply to sell them more stuff, when in fact childhood has never been safer; the rates of child mortality, injury and sexual abuse are lower today than at any time since records began. Cotton Wool Kids exposes the truth behind the scary stories and gives parents the information and the confidence to free themselves from the the treadmill of after-school activities and over-supervision that has become common today. The author provides parents with strategies to learn how to handle the relentless pressure from society and the media to provide a 'perfect' childhood and instead to raise their children with a more relaxed and joyful approach, more in touch with the outdoors and the community around them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 408

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Author’s note:

Certain details have been changed in the case studies in this book to protect the identities of those involved.

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Stella O’Malley, 2015

ISBN: 978 1 78117 320 6

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 321 3

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 322 0

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

‘Children learn to smile from their parents.’

Dr Suzuki

Introduction

Let’s get one thing straight – this isn’t another parenting book telling you how to raise your children or what you should be doing better. Instead this book seeks to explore childhood in twenty-first-century Ireland and to examine how the modern approach to parenting is impacting family life. I have been urged to write this book by countless clients who, after a course of counselling and psychotherapy, finally realised that to ensure their family is happy they often simply needed to focus on a pleasant lifestyle that suited their values and beliefs.

The weird and excessive cult of over-parenting that is promoted today as the gold standard of parenting isn’t working. An extensive range of extra-curricular activities, constant supervision, intensive schoolwork and expensive games are not only unnecessary, but often do more harm than good. In recent years, increasing numbers of stressed and exhausted clients are arriving at my clinic, primarily because the media, commercial interests and other outside forces have created an environment where both parents and children feel burdened by the weight of expectations and demands. Few among us would deny that parents are trying hard – too hard, perhaps – yet their efforts aren’t being rewarded, as a growing number of children feel increasingly consumed by fear and anxiety, and the number of teenagers and young adults also seeking counselling is growing. These ‘kidults’ don’t know who they are or what they want – they’re more in touch with what their parents want for them than with their own hopes and dreams. Parents feel embattled and worn out by external pressures, and their children are feeling stressed and anxious; something’s got to change … and soon.

It was in 2007, when I became pregnant with my first child, that I began to understand more profoundly the complex issues that face modern parents. After I had told everybody the good news, I quickly became unsettled by the overwhelming avalanche of well-meaning but frankly terrifying advice that came from every corner. This was the year that the Madeleine McCann kidnapping tragedy happened and the world was increasingly perceived as a dangerous place, filled with crazed, homicidal axe murderers. I diligently attempted to read all the baby books, trying to crack the nut that is parenting, but became confused when I realised that they all contradicted each other. I was also left feeling slightly bewildered when I realised that many of the baby books could be renamed simply as their special version of ‘what you’re doing wrong’.

During my ante-natal classes I was advised not to take my own mother’s advice too seriously as childhood is very different now, and was also warned not to listen to my friends, as they would probably tell fibs in a fever of competitive parenting. In addition, parenting books were cautioned against as ‘each child is different and you can’t do parenting by the book’. I nervously turned to my husband and asked him, ‘So where the hell can we go for advice?’

I had my second baby in 2009 and the paranoia and warnings continued relentlessly. In the hospital ward I started chatting with my neighbour in the bed beside me. She told me all about the elaborate monitoring system her husband had bought so that they could be sure their child would be safe at all times. This high-powered baby-tracking device was connected with an app to her iPhone and a quick glance at her phone would give her information about her baby’s breathing, temperature, movements, blood pressure and heart rate at any time she wanted. She planned to attach a tracking device to the child as soon as he was walking. ‘Is the child sick?’ I wondered anxiously. ‘Is there something wrong with him?’ She looked at me as if I was a blithering idiot. ‘No, of course not. There’s nothing wrong. You just can’t be too safe – it’s a sick world out there!’

But can you be too safe, I wondered. Is it really necessary for parents to monitor their babies every second of every day? And lying in my hospital bed, I couldn’t help but wonder whether childhood really has become so dangerous, or is all this a bit excessive? Has society really deteriorated so much – or are we worrying ourselves needlessly?

A leaflet in the hospital advised me to ‘keep an eye on your baby at all times’. ‘At all times,’ I wondered, feeling pretty fed up at this stage, ‘do they really mean “at all times”?’ As I was puzzling over this leaflet my husband, Henry, had taken our two-day-old son for a wander down the corridor. Henry was cuddling our little ’un in his arms and generally revelling in that oh-so-special tenderness that we have for our newborns when suddenly a siren started blaring loudly. I was in a public ward and all the mothers looked at each other in horror – wow, this really was a brave new world. Nurses and doctors flew to action stations to see who was trying to abduct a baby. Eventually, after a bit of a kerfuffle, it turned out that it was my husband who was the unknown male on the loose. Our son was tagged and Henry had walked too far along the corridor (not off the ward, not through any doors, merely further down the corridor), so the siren had gone off. When I (and everyone else in the ward) heard my husband’s stuttered explanation I thought, ‘Mother of Divine, they really do mean “at all times”.’

There and then I promised myself that when I emerged from the deep water of the early baby years I would one day do my own research and find out for myself whether parenting really needed to be so intensive, and if childhood really had changed so much since I was a child in the 1970s and 1980s.

Some time later, while writing a thesis on parenting in the twenty-first century, I was startled to discover that, despite the sensationalist stories in the media and hysterical tales of child abduction, the rates of child abduction and child murder by strangers are tiny and not increasing, and the rates of infant mortality in general have plummeted. In addition, the statistical rates of child sexual abuse in the developed world have declined an extraordinary 62 per cent since the early 1990s (even though children today are much more likely to report abuse).1 The rates for children becoming seriously ill have also tumbled – far fewer children die from accidental death and significantly fewer children experience trauma – so if we look at the actual evidence, it turns out that if it really is a sick world we live in today, it was a great deal sicker when today’s parents were children.

These could be the glory days of the parent-child relationship, and parents today have the opportunity to enjoy parenting in a way that our own parents and grandparents could never have dreamed of. But this isn’t what’s happening – instead parents seem to have missed the party. Psychologists are concerned about research showing that parents today don’t enjoy rearing their children as much as former generations did.2 Robin Simon, a professor of sociology and author of ‘The Joys of Parenthood, Reconsidered’ surveyed over 11,000 parents and reported that ‘Parents of young children report far more depression, emotional distress, and other negative emotions than non-parents’.3 Clearly something is rotten in the state of parenting.

But it doesn’t have to be like this – we parents could learn how to handle our hysterical and consumerist culture and simply enjoy raising our children. Hurrying to get to the latest supervised play arrangement could be swapped for children spending lazy days outside, unsupervised, playing with friends, exploring, building dens and riding their bikes. I can hear the shouts of dismay and derision already: ‘No, we just can’t do that! Life has changed! Children simply have to be raised in captivity; we have no other option! … You are being naïve, life has moved on!’ Yet after reading this book you will realise that life has indeed moved on: with levels of obesity, emotional problems, cyber-bullying, screen addiction, teen suicide, learning and behavioural difficulties increasing at a startling rate, the computer in your living room is much more likely to be a danger to your children than the tree in your local park.

Our perceptions of risk have been completely distorted by commercial interests whose sole reason for existing is to stalk parents and frighten them into buying more stuff. Big business has created a culture of fear and paranoia which has scared parents into thinking that they need to put lorryloads of effort into what comes naturally anyway. Not only that, but parents are now habitually regarded as incompetent fools who need extensive training to make up for their glaring inadequacies. We have gone from ‘Mother knows best’ to ‘the child is king’ in two short decades, and consequently parenting today has become incredibly demanding and stressful.

In a world obsessed with safety, progress and development, the culture of over-parenting is being sold by marketing maestros as the road to success, and yet over-parenting doesn’t improve the life of either the child or the parent – it merely adds to everybody’s stress levels. As Tom Hodgkinson, the author of The Idle Parent, has pointed out, ‘An unhealthy dose of the work ethic is threatening to wreck childhood.’4 This would perhaps be forgivable if children were happier but, sadly, they’re not. Both parents and children today are more anxious and discontented than ever before, despite children being safer, healthier and cleverer today than ever before.5 When 250 children aged eight to thirteen years old were asked in an extensive UNICEF study what they needed to make them happy, the results were an eye-opener: children want friendships, their own time and the outdoors.6 How often do we hear parents stating matter-of-factly, ‘It’s different now; we can’t give our children the freedom we so enjoyed as kids; times have changed’? And yes, in many ways times are different – but it’s not more dangerous.

We parents need to fight back against the culture of fear, and instead begin to address the true risks that are impacting our children. We needn’t fill our lives acting as social secretaries for our children, we needn’t ferry our children from dance class to drama to football, and we needn’t wrap them in cotton wool – rather we can simply send them out to play.

When I ask clients in my counselling practice to think back to the happiest moments of their childhood, with most it is the freedom that springs to mind; days spent with their pals on their bikes exploring, or roaming the fields, or building ever more complicated forts. Playing in houses with a responsible adult keeping an eye on the situation so that everyone shares nicely will not be remembered by our children with nostalgia, nor will primary-coloured plastic palaces throbbing with overstimulated children be a feature of our kids’ happy memories.

After reading this book, I hope that parents will learn to hold their heads up high and fight back against the creepy cult of over-parenting that has gained epic status for parents in the twenty-first century. This book is a call to arms, because a revolution in child-rearing needs to happen – parents and children need to be free to have fun again!

1 The Culture of Fear – It’s All About the Money!

Fear cuts deeper than swords.

George R. R. Martin, Game of Thrones1

It was 2007 and my husband and I were going shopping for our first baby’s cot mattress. We had been given a second-hand cot and even though we already had a perfectly good, barely used mattress at home, it was apparently deemed to be unconscionably dangerous to place my baby’s body on the second-hand mattress for even an afternoon nap (according to my experienced mother-friends, there were massive links between second-hand mattresses and cot death).

We were a bit mad at the time, you see, because we had just entered the peculiar la-la-land of the new parent. ‘Do you want the standard mattress or the specially designed one that is recommended by the Sudden Infant Death Association?’ demanded the sales assistant in a slightly aggressive manner. ‘Oh,’ I replied airily, ‘I’ll take the one that gives her cot death.’ Lack of sleep had rendered myself and my husband slightly hysterical, and we started laughing at my limp joke like hyenas on crack cocaine. ‘Two, in fact,’ shrieked my bleary-eyed sleep-deprived husband. The sales assistant wasn’t amused; she evidently thought we were cheapskate misers for even speaking about the cheaper, not-recommended-by-anyone mattress. ‘The standard mattress is €69 but the one that’s recommended by the Sudden Infant Death Association is €130. It’s up to you of course,’ she intoned.

I blinked. Wow, that was a seriously big difference in price! Was it not enough that I was buying a new mattress in the first place? Dare I defy death and choose the cheaper version (even though at €69, cheap it certainly wasn’t)? No, reader, I didn’t dare. Despite my gay laughter, I chose the expensive, gold-star, ‘recommended by the Sudden Infant Death Association’ mattress, all the while knowing that I had just been swizzed out of an extra €61 that we really couldn’t afford.

This is an example of exactly how parenting has been hijacked by marketing. Nowadays parents and children are big business – everywhere you look there are books, articles, programmes, websites, forums, blogs, educational toys and endless equipment and accessories that are described as essential for parents. It’s no longer enough to muddle through, relying on instinct and family wisdom – nowadays the ‘good enough’ parent is being replaced by the ‘super parent’, and clipping at the heels of the ‘super parent’ is the ‘ultra parent’.

And yet a scientific study called ‘Track Your Happiness’, which seeks to discover what makes life worth living, shows us that all this effort isn’t making for happy families. In this study an app is used to track people’s emotions as they go about their daily lives (see www.trackyourhappiness.org) and the data shows that on a list of people whose company they enjoy, parents rank their own children as low – very low.2 As Matthew Killingsworth, the lead researcher of the study, stated, ‘Interacting with your friends is better than interacting with your spouse, which is better than interacting with other relatives, which is better than interacting with acquaintances, which is better than interacting with children … Who are on a par with strangers.’3 Oh dear!

And perhaps this is why the (male) comedian, Louis C. K., developed a cult following among parents when he said in a Father’s Day skit, ‘You wanna know why your father spends so long on the toilet? Because he’s not sure he wants to be a father.’4

Not only that, but a seminal study led by the Nobel-Prize-winning behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman measured which activities gave working women most pleasure, and it turns out that minding children ranked a lowly sixteenth out of a choice of nineteen – behind exercising, having a nap, watching TV, even housework!5 If parents aren’t enjoying raising their children very much and children are increasingly falling prey to mental health issues, then we need to take some time to examine why the fun has gone from family life.

Why parenting has become so difficult

There are many reasons why parenting has become so difficult, but one of the more significant reasons is that children are no longer expected to be particularly useful. Since the end of the Second World War, childhood has been redefined and children have gone from being their parents’ unpaid employees to being their non-paying bosses. According to the sociologist, Viviana Zelizer, the modern child is ‘economically worthless but emotionally priceless’.6 There is no longer a system of reciprocity, with parents keeping their children fed and watered until they are old enough to kick something back. Instead, rather like a protected species, parents are nowadays encouraged to treat their children like a hyper-sensitive bonsai tree, which, to be raised successfully, must be kept in a certain climate with exactly the right amount of attention, stimulation and nutrition at precisely the right time.

Another reason parenting has become so difficult is because of the heightened expectations of what the arrival of children will do to their parents’ happiness levels. In previous years parenting was a given; you were a child, you grew up, you got married, you had children, you grew old and then you died. But today, because of contraception, parenting has become a choice, and so now when we choose to have children we expect that it will improve our lives in some way. We’ve seen the Hollywood movies, we’ve seen the gorgeous pictures in Laura Ashley of blooming expectant mothers in magical nurseries and so we have been taught to picture parenting as this soul-fulfilling and aesthetically pleasing calm journey to nirvana. But if it doesn’t turn out like that, we have so much invested in the experience, we tend to fall emotionally from a cliff with disappointment.

In addition, many parents are working too much and this has resulted in, among many other pressures, a lot of fights among husbands and wives about who is doing the childcare, the shopping, the household chores … and to what standard. The traditional masculine and feminine roles have disintegrated, with nothing to replace them; there is no rule book in this new world, with most couples being forced to slug it out until some sort of balance is found. As Jennifer Senior, author of All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenting, points out, women are working almost as much as men these days, and sometimes more: ‘women bring home the bacon, fry it up, serve it for breakfast, and use its greasy remains to make candles for their children’s science projects’.7 When the feminists were chaining themselves to the railings and burning their bras they perhaps didn’t give enough consideration to how the modern-day family would work out in practice – if the men and the women are both working, then who is minding the babies?

Sadly (for me, anyway) John Maynard Keynes’ prediction about a fifteen-hour working week has not happened. Instead, with the arrival of technology, has come the twenty-four-hour, seven-day week where many of us are pretty much always semi-working. This means that we parents are so time-pressed that we find we have very little time to spend with our children, and so we try to make the available time special. And so everything becomes even more heightened and burdened by expectation. Consequently, we tend to indulge our children during our precious free time to ensure that it is enjoyable for all the family, and perhaps this is why many of our children are spoilt.

Many sociologists argue that raising children has become so challenging because we live in a toxic culture where material goods and status are often given more value than time and pleasure. Cynical advertisers show us pictures of laughing, happy kids playing with the latest plastic crap that will apparently keep them entertained and laughing for hours. It doesn’t add up, because we know from bitter experience that the children won’t be laughing for hours, but the images are alluring and the children fall for it. And so they are pitted against their parents and begin their campaign of pester power; and maybe this is the biggest challenge for parents today: how to stop spending bucketloads of unnecessary cash when raising our children without feeling as though we’re ruining our children’s fun.

Parents driven by fear

‘Toxic parenthood’ is perhaps an accurate description of the pressure cooker that is parenting in the twenty-first century. In one generation, contemporary culture has changed at lightning speed, so that our own childhood bears little resemblance to our children’s experiences. Parents are expected to navigate between media sound-bites that proclaim hysterically the devastating impact of junk food, sugar highs, couch-potato kids, battery children, electronic babysitters, techno-brats and pester power, and many, many more potential hazards that are even today being dreamed up by sharp-suited, young, single and childless men in high-rise offices in cities like London or New York.

We have no way to compare our children’s experiences with our own childhood as we didn’t have the same issues to contend with: child obesity, learning and behavioural difficulties, food issues and child safety simply weren’t on the agenda then in the manner they are now. Brendan O’Connor declared in the Sunday Independent (14 April 2013):

In a balanced life, children wouldn’t feel like a chore, and the fact that they do sometimes says more about how modern life is out of kilter than it does about us or them. And that’s why we worry, about not creating the memories, about brushing them off, about not giving them enough attention, about being better parents, about not wasting the precious time … But modern life doesn’t allow that. Because in modern life we have to have it all. And when you have it all, you have nothing properly.

Parenting these days is perceived as a huge, momentous mountain to climb and so we parents worry that we will fail. This burden of expectation is crushing parents – but perhaps it is not parenting that has changed so considerably? Maybe it is society and the media’s expectations of parenting that have changed.

The culture of fear

In 1929 Charles F. Kettering, Director of General Motors, wrote an article called ‘Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied’, which (horribly) became almost a code of conduct for salesmen the world over. According to Kettering, the key to economic prosperity is the organised creation of dissatisfaction: ‘If everyone were satisfied no one would buy the new thing.’8 And this is why salesmen freak parents out with hideously scary stories – perhaps the most significant change that has occurred to parenting since our own childhood is not that childhood has become unsafe or more difficult, rather it is that commercial interests have cottoned on to the idea that they can make serious money from parent’s fears and anxieties.

Marketing, as we know, sells the sizzle not the sausage, and parents are being sold the fiendish promise that if they read all the books, the blogs and the forums, watch Supernanny, buy the apps, invest in the endless array of educational toys and DVDs, buy all the safety equipment and accessories, the organic brain food and the brain-enhancing multi-vitamins, then their children will be happier, safer, cleverer and more successful. This message is very powerful, but it’s not true … and it engenders vast levels of worry and guilt among parents.

Where has all the free fun gone?

In many ways, the easy-going nature of the spontaneous fun of children’s lives is morphing into a structured, supervised and costly exercise that parents have to work hard to provide. During the hot summer of 2013, the journalist Toby Young wrote nostalgically in the Daily Mail about his own childhood while decrying the need these days to make vast amounts of money if we want to entertain our children:

I now have four children of my own – three of them boys – and in many ways they have the same opportunity that I did. If they are lucky, and this spell of incredible weather lasts, they’ll have six glorious weeks ahead of them. They can ride their bikes, go pond-dipping and build a secret camp. It could be a summer they’ll remember for the rest of their lives just like 1976 was for me. But I don’t suppose they’ll do any of that.

For my children, the holidays mean more time to spend in front of screens, the kind you watch and the kind you play on. Instead of joining their friends outside for a game of football, it’ll be FIFA 13 and Score. They are products of the digital age; my memories of summers in the great outdoors seem to belong to the analogue era.

We have moved just one generation forward, but that summer of endless blue skies belongs to a different world. We queued in the street for water. My children expect to drink it encased in plastic. We had water fights with buckets. Mine expect a ride in a log-flume at a theme park.

So is it any wonder my four children can’t amuse themselves in the sunshine when they’ve been surrounded by electronic devices all their lives? Having been brought up on a diet of video games and Hollywood blockbusters, they’re unlikely to disappear into the woods to play cowboys and Indians.

At least they have the choice. Others will be penned in by parents worried about the traffic, or by an impossible schedule of improving activities, all organised by adults, most involving a car journey. If they do roam ‘free’ then they are sure to be linked to the mothership by mobile phone. The only way to persuade my kids to leave the house will be to organise a trip to Legoland or Alton Towers. Unfortunately, I’m not sure my bank manager will allow it. You think I’m exaggerating? When I went to Legoland last month to celebrate my five-year-old son’s birthday, the price of admission for two adults and five children was £304.50.9

If it costs, is it worth it?

It’s a cliché we’ve all heard – babies and toddlers get more entertainment from the box than the toy inside. Yet we continually fall for the sinister advertisers’ canny marketing: Oh yes, this toy is educational and creative, blah, blah, blah. My children’s favourite toys are several bizarre, flat, foam cushions (acquired by accident after they were used as props for an amateur dramatics performance) from which they can make houses, pretend to be in bed and create fences to jump over. Yes this is their best toy; not the child’s pink laptop, not the computerised train set, not even the jigsaws or the artist’s easel.

When we look at the rise and rise of the Hollywood-style Christmas experience, the elaborately eggsessive Easter egg hunts and the ‘supersize me’ childrens’ birthday parties, we soon realise just how much big business is leading the way in the creation of an unnecessarily expensive standard of operation that is causing crippling financial pressure on loving parents. Children’s birthday parties have become such heightened affairs that they are often a significant financial burden on parents. But just how crazy is that? All the children want is some cake and the chance to gather all their pals around for some fun.

And yet, if you are building a friendship with someone new, don’t you find that you are delighted to receive an invitation to their house? For me, an invitation to the house of an acquaintance is often a sign that our relationship is deepening. This is exactly how the children feel – they want to go to their friends’ houses because they want to know their friends on a deeper level. Just as we shouldn’t need to book an entertainer if we throw a dinner party (unless you’re on Come Dine With Me), we shouldn’t feel the need to book a clown or a bouncy castle, or professional cleaners, if we throw a children’s birthday party.

Products, products and more products

Going into a baby store today, customers are accosted by an enormous array of health and safety products that are ‘specially recommended’ by some organisation or other. I recently wandered through our local baby store and gazed in bewilderment at the latest gadget that will apparently prevent my child from opening the toilet lid and tumbling down the passageway to certain death.

We lucky parents can now buy stuff that supposedly protects our babies from table corners, electric sockets, steps, windows, taps, toilets, doors swinging shut, cupboards swinging open, containers, drawers and any number of relatively benign commonplace fixtures in our homes. There are also sun tents, sun shades, sun protectors, rain protectors, wind protectors, glass safety-film and elaborate stair gates that no man or beast can open. My husband and I (after much consideration, thought and discussion) didn’t buy a stair gate for our babies. We decided that we would prefer to teach our children to come down the stairs on their bum until they were able to walk down safely. Hardly revolutionary, but the look of shock and horror that appeared on other parents’ faces when they realised that There Was No Stair Gate On The Stairs In This House would have been funny if it wasn’t so unsettling. In the end we were given not one, not two, but three, stair gates by concerned friends and relatives. We didn’t use any of them.

FACT: The 1969–74 ‘Sesame Street: Old School’ DVD is nowadays recommended ‘For Adult Viewing Only’. ‘Why?’ you may ask. The answer is because it is apparently wildly dangerous. You see, happy children playing Follow the Leader, climbing through a giant pipe, balancing on a piece of wood, and weaving through sheets that are drying on a line is now considered so dangerous that the DVD is banned for children in the twenty-first century. Even though at the time it was considered ideal and even educational.10

Thudguard®, a helmet for toddlers to wear when they are learning to walk, costs nervous parents between £21.99 and £29.99, and, by the way, it isn’t suitable for ‘pedal cyclists, skateboarders and rollerskaters’. This helmet is specifically for toddlers to wear as they are learning to walk. And presumably when the child is deemed fit to walk without a helmet, the responsible parent should then bring the child around the house pointing out dangerous spots where the child might fall and hurt himself – because, of course, the child won’t have figured that out for himself.

As well as providing statistics about child head injuries, the Thudguard® helmet is endorsed by testimonials from respected professionals – from neurophysiologists to psychiatrists – which further convince parents that this helmet is an essential part of the kit that every safety conscious parent must buy before any lasting damage is done to their toddlers’ heads.11 The message is very convincing – apparently there are 318,575 baby and toddler head injuries recorded every year. However, what is not stated is how many of these head injuries are minor bruises and scrapes – indeed, I would venture the opinion that in 2009 my daughter (a livewire) might have accounted for approximately 118,000 of those bruises!

It’s all about the money

Perhaps the most annoying gadget for the new parent is the new extreme baby-tracking monitor. Yes, it’s not enough to hear the baby crying from down the hallway; instead we need to have a fully amplified version right next to our bed so that we jump up in terror six times nightly every time the baby stirs. Not only that, but we now need to be able to view the baby with a video that films it as it sleeps; we also apparently need an app on our phone so that we know how often the baby’s body position changes, its heart rate, skin temperature, blood oxygen level and sleep quality at any given moment.

The grand promise with these monitors is they are a means of assuaging parents’ worries, giving us peace of mind and freeing us to concentrate on other activities, but of course, as we all know deep down, it’s a false promise. In truth, many of these gadgets merely serve to up the ante – they give us more to worry about, create more expectation, and more is then asked of us, which of course, causes more pressure and stress.

The biggest fear of parents of new babies is sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and with good reason, as SIDS is a leading cause of early infant death. But unfortunately, the cause of SIDS is still uncertain (though current research points to underlying issues) and hi-tech monitors don’t actually cure SIDS. What are we to do? Commercial interests design and advertise products in the hope of triggering parents’ fears, some of us fall for it and then talk it up, and the heightened conversation creates a buzz of worry among parents. If we snigger at these extreme-worst-case-scenario products we soon feel foolhardy in the face of other parents’ disapproval and so all too often we inwardly roll our eyes and join ’em.

More experienced parents may smirk as they read this, smugly satisfied that they no longer fall for cynical marketing ploys directed at nervous first-timers. However, it is mainly new parents who are the target market, and they’re not smirking; the sharp rise in the production of extreme safety gadgets for babies is currently being exploited by canny businessmen. If you were to buy the Owlet Baby Monitor, a ‘proactive health monitor’, it would set you back a hefty €185. Considering that the estimated spend of parents on babycare products in the UK before the birth is £1,619; which equates to a staggering £492 million every year, this is very big business12 – a business that makes parents feel anxious, fearful, flawed … and broke.

Risk compensation

The annoying part of all this emphasis on safe-proofing is that it has been proved that humans tend to compensate for risk when they use safety equipment – they drive faster when they wear a safety belt and take more risks when they feel more protected by the equipment.13 For example, David Ball, a professor of risk management at Middlesex University, analysed injury statistics and found that ‘The advent of all these special surfaces for playgrounds has contributed very little, if anything at all, to the safety of children.’14 The children don’t worry so much about falling on the rubber, so they’re not as careful. Don’t get me wrong, those rubber floors on the playgrounds are brilliant – they must prevent millions of cut knees every day – but, because of our innate tendency to compensate for risk, human beings tend to behave in a more reckless manner when they have a safety net. And this is why the rubber surfaces don’t prevent more serious accidents. Every so often random, freak and tragic accidents occur, and apart from perhaps hoping that we are mentally robust enough to be able to cope should the tragedy land on our shoulders, beyond that there is nothing we can do about it.

Case Study

Fiona attended counselling to treat anxiety related to her only son. Jamie was a bright little nine-year-old boy who was becoming increasingly resentful of his mother’s tendency to over-protect him. At our first meeting, Fiona described how she was living on a knife-edge, consumed with dread and fear that ‘something terrible’ would happen to her child. This irrational anxiety had spilled into every aspect of her life.

She finally decided to attend counselling as a consequence of a school tour that had gone disastrously wrong. ‘I had tried to volunteer as a helper for the school tour, just like I had in other years, but they didn’t need me this year. I was incredibly fearful of Jamie on the bus on his own and on the school tour – so I decided to follow the bus on the school tour. I know it was a bit mad but I felt so anxious. When we got to the aquarium I noticed the adults present looked a bit harassed so I thought I’d stay nearby in case the children needed some extra supervision. I honestly thought I was being unobtrusive. But the other kids in the class noticed me and they started to mock Jamie that his mother was stalking him. He was absolutely furious with me and he’s barely speaking to me now.’

As the counselling process proceeded, Fiona further explored her fears and anxieties about Jamie and it emerged that it was predominantly based on the scary stories she had looked up on Internet news sites. Fiona was unhappy and bored in her job and tended to use the Internet as a means of escape. She would then become gripped by the latest horror story on the net, and fearful for her son. Fiona also worked very long hours and was consumed by guilt that Jamie was more often than not being minded by childcare professionals, and so she tried to make up for her ‘neglect’ by over-protecting her son when she had the chance. It had become a warped demonstration of her love for him.

Fiona finally learned to loosen the reins on Jamie as we worked together to test the validity of her beliefs. The more she educated herself about the subject, the less she found to fear. Within the counselling context, Fiona also engaged in a regular programme of creative visualisation to help her to envisage a happy future for herself and her child. In addition, we collaborated to challenge her habit of seeking out horror stories to further frighten herself. Eventually Fiona’s anxiety reduced to more manageable levels and she now repeats some personal mantras to herself to ensure she keeps her tendency to magnify her fears in check. She also chose to change her job and spend more time with her son, thereby reducing her need to over-compensate

If it bleeds, it leads

The media is (mis-)leading the way for parents to believe that children must be cosseted, comforted and kept wrapped up in cotton wool at all times. Papers sell if they have a scary message to deliver – sales don’t increase if the headline reads, ‘Life is fairly good for many people these days’. And so, even though crime is down, the reporting of crime in the media is up. A recent study of newspaper coverage from the University of Toronto found that there was a new homicide reported every single day in the Toronto newspaper over the course of a year.15 This was strange, because that year there were 68 homicides in Toronto, not 365. So how could a new one appear every day? The answer was that if there wasn’t a local murder to report, the media went outside the city to find one. Simply put, the media needs to sell papers, violent and terrible crime sells papers, hence we read about horrible crimes constantly. For the media, chilling crimes are a money-spinner.

Our parents’ generation did not have to negotiate the same levels of anxiety as today’s parents. In years gone by, tragedies involving children being murdered, raped and abused were reported as serious news, not as gruesome shockers, magnified and sensationalised so as to sell more papers. Michele Elliot, psychologist and founder and director of the child protection charity Kidscape, points out that ‘It is no good asking our own mothers for advice … when they were bringing us up, they didn’t seem to be hit by shocking news of yet another child murder.’16 (And this is why these days grandparents are often even more neurotic than parents, even though when they were raising their own kids they were decidedly laissez-faire – the grandparents too have been infected by hysterical media sensations). But, as we shall see later, neuroscience shows that the more frequently a person views horrific pictures, the more feelings of anxiety they induce, and so the explosion of sensationalist journalism has heightened our sense of anxiety simply to make more money.

In truth, the rates of child abduction remain static: once in a blue moon a child will be abducted; however this is an incredibly rare phenomenon (which will be examined in Chapter 2). Even though the rate of child abduction, just like child murder, remains tiny and constant, our perception of this has changed utterly: it is readily accepted among sociologists and crime experts that it is much safer to be a child in 2015 than it was in 1985, but it is the rare parent who would accept this.

How we’ve changed

Ireland’s dark history of children being abused at the hands of the local clergy, and orphans in institutions being subjected to horrific physical and sexual abuse has left a deep mark on the people and we are now trying to make good the damage caused by the secrets of the past. As a country, Ireland has moved on from being riddled with hypocrisy, lies and dirty secrets to become a nation that is working valiantly to provide a safe and open society. Thankfully, in this new era of enlightened attitudes to sex, children are recovering more quickly from incidences of sexual abuse and appear to be less affected by their experiences as a consequence of counselling and understanding from society. Not only that, but thanks to widespread education practices and safety programmes, children these days are much more likely to tell their parents if they are subjected to unsavoury behaviour, and, unlike in years past, children now are usually believed. And so, unlikely as it may appear, we children of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s were much more likely to be abused than are our children, and we were much more likely to be deeply affected by the experience.

This is one of the many reasons why it is significantly safer to be a child in Ireland today than it was in the 1980s. In fact, today’s kids are the safest kids that have ever lived. There was an explosion of interest in the media in 2013 when two Roma children in Ireland were taken from their families by the state because they had a different hair colour and complexion than their siblings. Then there was a shocked outcry when it emerged that in fact any suspicions about them having been taken from their true family were untrue, and were based on very flimsy evidence that seemed to be a direct consequence of racial profiling. The outcry from the media was enormous; however, there was a strident backlash that argued that strong-arm tactics such as these were necessary. One commentator on national radio argued that we as a society must put up with incidents such as this – ‘I don’t care if 10,000 children are taken from their homes if it saves just one child’s life’.17

But what does this mean? Children removed without argument from their homes because of random suspicions on Facebook? A society oppressed by suspicion and paranoia, and communities living in fear and dread of the child-snatcher? Or would it be more beneficial if the media was subject to consistent guidelines set down so as to inform rather than promote suspicion, fear and paranoia in our society? Thinking that anything is allowable ‘if it saves even one child’ is a crazy thought process. If 10,000 children could be taken from their homes by the police, without their parents’ consent, to save just one life, we would be living in a fascist state. It would be a country filled with misery, anger and a deep mistrust of the authorities. If this well-regarded broadcaster really thinks any amount of hassle and distress would be worth it to save just one child’s life, then he should really be encouraging us all to stop driving – that would save a child’s life within the week.

Exploring road safety

Road traffic accidents pose a far greater threat to children’s lives than child abduction does. But contemplating risk is a funny thing. We don’t like to be reminded that we are all simply part of a statistical mass that will inevitably one day get sick and die. We prefer to forget that more kids die in the back of a car than playing on the streets, and that every time we load the kids into the car we are putting both the children and ourselves at risk. Instead, in a strange way, we prefer to dwell on the unlikely event of child abduction, or the implications of a pylon being erected in the area, or some other rare and random danger.

Living in an area with pylons will probably cause the death of one child through leukaemia every ten to twenty years, and many people become very upset about this. But when we hear that there are an average of fourteen deaths every month on the roads – approximately 168 deaths per year – we don’t really do very much about it.18 We know we could stop driving, but we don’t. We shudder inwardly when we hear that 30 per cent of these deaths are of young people aged twenty-five and under, and we shiver when we are reminded that the most dangerous time of the day or night on the roads is between 4 p.m. and 6 p.m. – when parents are most often in the car taking kids to activities – and that most accidents happen within five miles of home.19 We all know it’s all a terrible tragedy. We all know we should slow down. But often we don’t. And we won’t stop using the car. Absolutely no way. The car is essential. Because we need our cars, we like our cars, and so we are prepared to live with that particular risk. And so the debate rages on.

But road accidents don’t sell papers, so the media doesn’t explode every time there is a tragedy on the road – a small factual paragraph is usually deemed sufficient. So our culture teaches us to accept road accidents as a necessary but tragic part of life, but to lose our heads over child abduction. Parents react to this culture accordingly; we become obsessed with supervision and the random possibility of child abduction and other unlikely dangers, while dismissing the very real danger of road accidents, saying, ‘Sure, you can’t live like that, you’d go mad!’

Perceptions of risk

If an adult (in 1885, 1985 or in 2015) wishes to abduct a child there is very little that can be done to prevent this; the adult merely needs to regularly visit areas where children are playing and eventually the chance to abduct a child will present itself. The first child might resist and so might the second, but eventually a child will unquestioningly do as the predator says. But the sad fact is that most predators go to the poorest areas of the world to prey upon children: it is there where we really should worry about children’s welfare.

Child sex tourism plays an increasingly large part in the world’s tourist market; for example, a UNICEF study has reported that over 30 per cent of children aged between twelve and eighteen in Kenya are involved in the sex tourism business.20 And an estimated third of all prostitutes in Cambodia are underage.21 Child sex tourism is estimated to be a multi-billion euro illegal industry which is steadily growing, and a US department has reported on fake fishing expeditions to the Amazon which in reality are child sex tours for European and American paedophiles and sexual predators.22

If you were to read a book entirely about the risk of child abduction, then 99 per cent of the book would be about children from places such as Thailand or Brazil being prostituted to wealthy older men from richer countries. Barely even one sentence in the book would be given over to middle-class concerns about the highly unlikely possibility of Irish children from intact homes being abducted – except perhaps to say that parents worry excessively about it. We don’t tend to fret over the unlikely event of our children contracting some rare and dreadful disease and dying; and nor should we. In much the same way, we shouldn’t spend much time worrying ourselves about child abduction when there are more real concerns regarding children’s health, such as depression, anxiety and other mental health issues that are, certainly in comparison to child abduction, quite common.

Rare and random tragedies, such as being struck by lightning or being abducted, are largely unpreventable. But there is much we can do to change the phenomenal suicide rate and the growth in mental health issues amongst young people. Problems with mental health are the largest source of ill health in our young people in Ireland today,23 and when we realise that ten to fourteen people die by suicide every week in Ireland it soon becomes apparent that our eye seems to be on entirely the wrong ball (see boxed text and Figure 1.1).24 Joylessness, depression, anxiety and mental ill health are causing more misery in Ireland today than stranger child abduction.

In Ireland every year, approximately:

• 450–700 people die by suicide.

• 12,000 people are admitted to hospital for reasons of self-harm (using methods such as attempted hanging, poisoning and cutting).

• 93,000 adolescents (20%) experience psychological problems.