10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

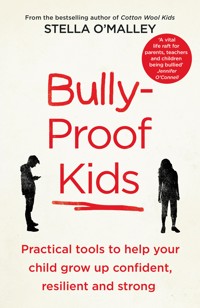

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

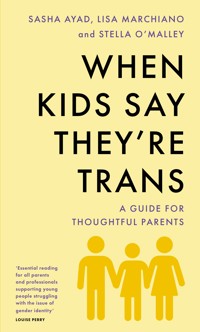

We can't always be there to protect our kids as they make their way in the world. What we can do is equip them with the tools they need to ensure they have a positive social experience. Based on many years' experience counselling bullies and targets, Stella O'Malley offers concrete strategies to empower children and teenagers to deal confidently with bullying and dominant characters. She identifies effective ways for families to cope when bullying occurs, including approaching the school authorities, communicating with the bully's parents and tips to tackle cyberbullying. Stella's common-sense approach will help your child, tween or teen to develop their emotional intelligence and will provide relief for families navigating the rapidly changing social environment, both online and in school.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Stella O’Malley is a psychotherapist, writer and public speaker with many years’ experience as a mental health professional. Much of Stella’s counselling and teaching work is with parents and young people. She is the author of the bestselling book Cotton Wool Kids.

SWIFT PRESS

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2022 First published in Ireland by Gill Books 2017

Copyright © Stella O’Malley 2017

The right of Stella O’Malley to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Designed by Síofra Murphy Edited by Sheila Armstrong

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800750616 eISBN: 9781800750623

Acknowledgements

I am often perplexed and unsure how to react when my friends and family assume that my work as a psychotherapist is draining or debilitating in some way. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. My work has so far always been energy-giving and inspiring as the clients I work with are sensitive and generous enough to seek help and then willing to face the obstacles that invariably appear along the way. This book wouldn’t have happened if not for the clients that I have been lucky enough to meet and I’d like to take this opportunity to give them my heartfelt thanks.

The book wouldn’t have crossed over the line without the discernment and engagement of Sarah Liddy, so thanks for that. I’m also thankful to Sheila Armstrong, Teresa Daly and to everyone at Gill Books for their clear-minded judgement calls.

To my lovely Henry and darling kids, Róisín and Muiris, thanks again for your forbearance and patience about ‘the book’. Thanks too to the fabulous author Nuala O’Connor who is so kind in steering me the right way in the world of publishing, to Katherine Lynch for her kind generosity and to my pal, therapist and confidante Fiona Hoban for her insight and sincere encouragement. Finally, infinite thanks and love to my Mam, my family and my friends.

‘Don’t shrink. Don’t puff up. Just stand your sacred ground.’

Brené Brown

Contents

Introduction

1 Defining bullying: What is and what isn’t bullying?

Why do some people bully?

Human nature and our competitive culture

The neuroscience of bullying

The difference between bullying and conflict

Over-protected ‘cotton wool kids’

2 Complicated relationships: Frenemies and power plays

Psychosocial stages and personality types

Popularity and the social hierarchy

Relational aggression

The controlling friend

Humour and teasing

Frenemies and toxicity

Teen drama, gossip and hormones

3 The bully and the crew: Lions, hyenas and antelopes

The ‘pure’ bully

Bully or failed leader?

The victim-bully

The bully’s crew

Nurturing the nature: good and evil

4 The target: Tall poppies, provocative victims and gentle souls

The impact of bullying

Why are some people targeted?

Tall poppy syndrome

The passive target

When targets play the clown

The accidental target

Handling difference and promoting tolerance

Victim-blaming and victim-shaming

The provocative target

Children who play the victim

From victim to survivor

5 The bystanders: The untapped strength of the upstanders

‘The bystander effect’

Pluralistic ignorance and audience modelling

The diffusion of responsibility

Deindividuation

Blaming the target and blaming others

Bystander fear and lack of confidence

Dehumanising the target

When parents and teachers are the bystanders

The bystanders in Nazi Germany

‘Be the arrow, not the target’

6 The bullying environment: Group cohesion and competitiveness

The school environment

Handling difference

Cohesion and competitiveness

Group identity

The perfect bullying environment

Being your child’s advocate

What you can do

7 Cyberbullying: Trolls, hate mail and sextortion

Keyboard warriors

Hate mail

Anonymous apps

Check your tech

Sextortion and scammers

Protective measures

8 How to stop bullying: Practical tips

How to handle yourself

How to open a dialogue with your child

How to communicate with the school

How to introduce school initiatives

How to handle the unhelpful school

How to handle the bully’s parents

How to identify the bully’s motivations

How to develop emotional intelligence

How to help children adapt to their environment

How to deal with violent bullying

How to support your child during bullying

9 Recovering from bullying: Stronger than ever before

Living well is the best revenge

Increased inner strength

The gift of resilience

Improved emotional intelligence

Improved social skills and relationships

Increased inner confidence

Increased empathy and understanding

Increased moral engagement

A flexible mindset

Bibliotherapy and the comfort of the arts

Rebuilding the parent–child bond

Character development

The holistic approach

Resources

References

For my darling kiddos, Róisín & Muiris

Introduction

Every day children in schools all around the world eat their lunch in toilet cubicles; others spend entire mornings in class silently agonising about who might hang out with them at lunchtime; millions immediately panic when they hear the familiar ping from their mobile and they realise that yet another so-called friend has posted spiteful venom about them on social media.

As a psychotherapist, I felt compelled to write this book in response to the sheer number of people who come to me whose lives have been blighted by bullying. Parents come to me because they are devastated that their children are being bullied. Kids who are being bullied also come to me and the bewildered pain that often characterises the initial sessions is harrowing. Not only that, but I also often work with children who find the social aspect of their lives difficult – the kids who are hanging on the edges of the group. These kids feel they don’t quite ‘fit in’ – and they aren’t even sure they want to – but they live in a world obsessed with popularity, with sociability and with counting ‘likes’ on their social media.

It is estimated that approximately 10–15% of any given group of children repeatedly bully others while approximately 10–15% of children are repeatedly targeted by bullies. Although physical bullying decreases with age, on the other hand verbal, social and cyberbullying peaks between the ages of 10 and 15.1 Thankfully, as teenagers grow older they bully less and usually by the time they leave school the prevalence of bullying is significantly reduced.

Although girls are more likely to use social bullying as a way to wield power over another while boys tend to use physical violence more often, it doesn’t really matter whether the bullying is physical, social, emotional or cyber – bullying reaches deep into a person’s psyche and shatters the sense of self. Girls might be subtler – using gossip and exclusion – while boys are more obvious and yet boys tend to bully more often and they keep at it longer.2 The child who has been bullied often feels deep down that they have been viewed, judged and then stamped as not good enough and their trust in other people’s goodness is destroyed. The thing about bullying is that the humiliation and shame is almost overwhelming. Each little kid who has been bullied thinks that this is their individual failure and they usually blame themselves. They may feel relieved and even vindicated 20 years later when they discover that it wasn't their fault, nor were they alone in their experience, but the anguish of being abandoned and humiliated by their peers at a crucial stage of development often leaves many long-term scars.

Within the counselling context, I often meet many children whose disdainful attitude towards the ‘loners’ and ‘freaks’ in their social domain is downright disturbing. When I challenge these otherwise considerate and kind kids, they tend to look bemused, shrug their shoulders and mindlessly dismiss the pain of their peers. Other bystanders wring their hands in concern but tend not to do anything that will actually help the target. Schools, usually more focused on children’s education than their emotional well-being, tend to hope the exclusion or the bullying might be a molehill rather than a mountain and so they tend to underplay any bullying. The target is often so humiliated by the experience that they prefer to keep their head down and wish it all away. This is another reason why I wrote this book and the dismissive dehumanisation of other people’s pain is one of the many issues involving bullying that I became determined to address.

The good news is that bullying can be combated. The bad news is that not enough people are educated about how to do this. This book intends to ensure that readers are fully equipped to handle any bullying that comes their way – no matter what their role is.

I work in a private practice in the midlands in Ireland and of the three second-level schools in the area, one of the schools appears to handle bullying very effectively, another does reasonably well, while the third school encounters bullying on an almost continuous basis. This is remarkable to me as the kids are all from mostly similar backgrounds. The difference is that this school minimises any bullying incidents or pretends that there is no bullying taking place, while the other two schools are, to a greater or lesser extent, willing to address the problem and take the necessary steps to deal with it.

This book explores the dark world of bullying and examines how and why some approaches are more successful than others. In this book, readers will learn about strategies that will combat bullying and exclusion. The reasons why people bully, why some personalities try to gain power over their peers, why some people are targeted more than others and why bystanders don’t intervene are all examined. Different approaches are outlined so that targets can recover from their experiences and be able to move forward with confidence, self-awareness and self-acceptance.

Many parents and teachers deal with bullying by saying, ‘Don’t bully’, or else ‘Stand up to them’ or ‘Laugh it off’. Sadly, this advice seldom works and a much more comprehensive approach is needed to handle this complex issue. In addition, many parents tend to look the other way and pretend that bullying and social exclusion isn’t happening the length and breadth of the country; then when it hits their own family they often feel isolated and disheartened by other people’s lack of solidarity. After reading this book, readers will have a more complete understanding of these issues and an insight into how best to respond to bullying and complex social situations for preteens and teenagers.

There is no silver bullet. Insight, self-awareness and emotional intelligence aren't developed in a day, but kids who always feel on the edge of things, kids who kill time at their locker every day because they find the complex manoeuvrings of their peers difficult to deal with; these kids need to be helped to improve their social skills. It isn't appropriate to protect children from everything but, as a parent, it is our role to help our children when they need it. This book will help parents to support their kids in their quest to become bully-proof.

1

Defining bullying

What is and what isn’t bullying?

‘First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.’

Mahatma Gandhi

‘The first time things went wrong for me as a child was when I was bullied by my classmates’ ... ‘I think everything began to fall apart when I got bullied as a kid’ ... ‘I lost my self-confidence when I was a child and I fell out with my friends’ ... Variations of this sentence are being heard today and every day by counsellors and healers in therapy rooms all over the world. When I first worked as a psychotherapist, initially I was astonished by how many clients traced their first feelings of depression or anxiety or other mental health issues back to when they were bullied or excluded as a child, but as the years went by, I have now come to expect it.

According to Dr James O’Higgins Norman, director of the National Anti-Bullying Centre in Dublin City University, bullying can be described as ‘repeated, aggressive behaviour by somebody with more power’.3 Bullying, often deliberate and premeditated, tends to occur over a prolonged period of time. Bullying behaviour generally peaks at about age 12 while cyberbullying peaks at about age 15, but as anyone who has experienced a bullying boss will tell you, it certainly isn’t confined to those years.4 Bullies, of course, ultimately bear the responsibility for hurting others. However, if we wish to understand what is motivating bullies, then we must go beyond assigning blame and begin to properly analyse this area so that we can become much better at figuring out how to reduce the impact, intensity and frequency of bullying.

There are many different types of bullying, but the following analysis, taken from reachout.com, classifies the main types of bullying:

• Verbal – you’re probably familiar with this one. It’s name-calling, put-downs, mocking or threats. It can be face-to-face, written or, often, over the phone. It can also include sexual harassment.

• Physical – being punched, tripped, kicked or having your stuff stolen or damaged. It can also include sexual abuse.

• Social – being left out, ignored or having rumours spread about you. Often one of the hardest types of bullying to recognise and deal with.

• Psychological – this type of intimidation can also be hard to pin-point – dirty looks, stalking, manipulation, unpredictable reactions. It’s often less direct than other types of bullying and you can feel like it’s all in your head.

• Cyberbullying – being slagged off or harassed by email, text, on social networking sites or having your account hacked into. This is a new-ish and pretty tough type of bullying, because you can feel like there’s no let-up from it.5

Why do some people bully?

Through examining nature, we can see that living things have the instinctual desire to gain some power and control over their environment so that they improve their chances of survival. When this need is met the body feels satisfied.

Many humans and animals also have, to a greater or lesser extent, an innate desire to herd together and create a pecking order. There is a valid reason why animals and humans tend to form groups. Weaker animals need the herd so that the stronger animals can protect them, and it is easier for animals to survive in a herd than all alone.

The term ‘pecking order’ (originally used to describe the hierarchical behaviour of chickens) describes the system of social organisation that many animal species, including humans, live by. Among animals, a chain of command can be very helpful as it clarifies the situation; everybody is assigned a role and so the group works together more effectively.

This instinctive need among animals and humans to create a pecking order is intensified during times of stress and conflict. And so, if our country is at war, we need our leaders to be very powerful if we are to win. Similarly, if a group is being attacked, the need for a pecking order becomes heightened. Sadly, many children often feel threatened because of the competitive elements in our society and so they tend to establish pecking orders everywhere they go – these kids feel the need for a leader or a couple of leaders because they feel insecure without one. Their insecurity compels them to create clearly defined roles for everyone in the group so that they can feel safer within the group.

It is the weaker animals that especially need the pack to be strong if they are to prosper and so they are often more defensive of the group than the stronger members. Weaker members are often hostile towards outsiders because they feel more threatened; they feel their position in the pack is at risk, they are concerned about the cohesiveness of the pack and they resist change for fear that they will be disadvantaged by it. If newcomers were allowed to easily come and go then the pack wouldn’t be cohesive and strong. Consequently, sometimes it is the weaker sidekick who convinces the powerful bully to side-line and isolate the newbie in any group.

Of course, not many sidekicks are aware of their primal instinct to protect the purity of the pack. Instead, weaker members simply have an irresistible urge to see off the newcomers and to put them in their place – firmly outside the pack.

The reality of a pecking order among little boys became very clear to me recently when my six-year-old boy started soccer training. I was simply amazed how often my gentle little boy was suddenly embroiled in fistfights with other kids on the pitch. During training sessions a minor disagreement would have boys knocking the heads off one another quicker than you could say ‘pecking order’. My boy, who was the newest kid on the block, seemed to be in a handful of fights during every training session for the first few weeks. A few months in and the boys seemed to have established who’s who and there are very few outbreaks of violence nowadays. Meanwhile, my eight-year-old daughter – a significantly more assertive person than my son – has never, to my knowledge, been involved in a fistfight.

Although the gender gap is shrinking every day, it still remains the case that girls tend to establish a pecking order in a more subtle and guarded manner. When my daughter, Róisín, first went to dance class there was an intensely silent examination of each girl’s clothes, demeanour, attractiveness and general popularity so that the pecking order could be established. Now that everyone knows who they are and their relative position on the social totem pole, the girls can get on with enjoying each other’s company and learning how to dance. However, if anyone decides to act out of character in this dance class, then I have no doubt that intense stares and comments will put the imprudent girl back in her box very quickly.

Human nature and our competitive culture

Psychologists agree that all humans – every one of us – have an inborn emotional need for power or status of some kind. This need can vary across a spectrum from a very high to a very low need depending on the person. For some people their need for power is relatively low and can be easily met – for example, the child who feels satisfyingly powerful when they ride a bike or learn to play a game with their friends. However, other children have a more developed need for power and they tend to try to dominate any given situation. Children like this often have ambitious and powerful personalities and they can be very competitive. These kids with a high need for power often like to win because they have a stronger need to appear in control and they like to be the top dog.

The problem with the varying human need for power is that because of the limited natural resources on the planet, people with a strong need for power can tend to consume those who are less inclined to seek domination. Not only that, but our limited resources mean that there is always a certain level of competition going on in the world – not everyone can be rich – and so it is often those with the highest need for power, those who are most willing to fight for ascendancy and ‘beat’ everyone else, who are most likely to end up rich.

Our tendency to herd together is often finely balanced with our propensity to compete with members of our group for limited resources. The inhabitants of some communities won’t survive unless they depend on their neighbours, and so, in these communities, towns and villages, a supportive and co-operative culture is nurtured. However, people who live in wealthier countries usually don’t need to rely upon others to survive – they can get by just fine without depending on the village – and these people usually have a strong need to protect what they have already gathered.

This is arguably why people who are wealthier have a more individualistic outlook and tend to satisfy their need for power by protecting what they have, by ensuring others don’t rise as high as they do and by competing with everyone else in their circle. Oliver James’ polemical book Status Anxiety further details how and why the more materialistic and commercially driven societies tend to be more competitive, aggressive, individualistic, selfish and bullying.

To thrive in life, according to Western ideology, we must ‘beat’ everyone else. But we can’t all beat everyone else and so there are many who fall victim to the ‘winner-takes-all’ belief. Many adults today teach children the misguided message that beating everyone else is the most impressive thing they can do. The problem with this is that in a world obsessed with success, with beating your opponents, with becoming ‘the best’, we are inadvertently creating a culture of bullying. Popular shows like Britain’s Got Talent or The Apprentice tend to glorify bullies and a whole slew of video games from Call of Duty to Clash of Clans glorify violence in the name of entertainment. The rise of charismatic leaders who are also perceived as bullies, such as Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump, is another indication that these days we tend to give more respect to powerful bullies than we do to gentler, more reflective people. If influential adults encourage this ‘winner-takes-all’ attitude then it is unrealistic to expect children not to attempt to gain ascendancy over whoever they can – and, sadly, the easiest person to target is often the one kid in the room who especially needs compassion and gentleness.

Social media, although designed to bring us together, also drives us apart as we continuously count our ‘likes’ and our ‘friends’ and quantify our social standing by comparing ourselves to others every time we go on social media. Even the education system whereby children enter college promotes the ‘winner-takes-all’ ideology. The system of entry into third-level education is structured so that every candidate is competing against their peers, so if you just happen to be in a year where there are an unusual number of clever swots then you will undoubtedly find it a good deal harder to get into your preferred university course.

Compared to even fifty years ago, most of us in the Western world are relatively wealthy; it is unlikely that we will starve to death, contract a disease from malnutrition or find ourselves homeless with no shelter. But, rather than rejoicing in our good fortune, the human instinct for power motivates us to further control our environment, to protect our wealth and to seek further riches, better holidays and more ‘stuff’.

The problem with our focus on 'stuff' and success is that it creates a harder society; a society that accepts power as a 'better' quality.

Children who are bullied are more likely to ‘pass it on’ and families that accept bullying as an effective form of getting what you want are naturally more likely to produce children who bully. These families are also, unfortunately, more likely to produce more people who are targeted by bullies as the gentler personalities within the family have become accustomed to being targeted.

‘My father was a bully. He punched, kicked, roared and screamed until he got his way. My mother was a doormat and I made the conscious decision never to allow anyone treat me the way my father treated my mother. In many ways it was inevitable that I would become a bully. I had dyslexia and I was useless in school but I was determined not to be treated badly by anyone. So it was a case of shoot first before they shot me. I bullied the “swots” mercilessly. I slagged them, imitated their voices and physically hurt them at every opportunity.

I remember in primary school one unfortunate boy shat his pants in school and I kicked his arse all the way home. The excrement all went up his back and down his trousers until it spilled out. Poor kid, he was a couple of years younger than me. I knew everyone was wary of me and it felt good –– I felt powerful.

It wasn’t until I was all grown up and my own little girl was in school and she was bullied that I realised the harm I had caused. I’ve undergone a transformation since then but you could say that karma has caught up with me as my little girl seems to be filled with self-loathing as a result of all the bullying that she has experienced.’

Shay, 41

The neuroscience of bullying

The ground-breaking work that has been done on the brain in recent years has inspired many new theories on bullying. It is now known that the amygdala in our brain serves to trigger our ‘fight or flight’ response. Some psychologists argue that a third and fourth response can also be triggered – 'fight or flight, freeze or appease'. When we believe we are being attacked – whether by a mugger in a dark alley, by a lion in the jungle or by an aggressive, power-seeking kid on the first day of soccer training – we tend to act first and think later. Some of us stand and fight, some of us run for the hills, some of us freeze completely and some of us try to appease the aggressor. It is only later on that we tend to analyse and try to figure out whether we behaved correctly or not.

If we take into account the animal instinct to establish a herd or a community that makes each member feel stronger, and combine it with our knowledge about the amygdala, it soon becomes even more understandable why the weaker, more insecure individuals – the sidekicks – often encourage their stronger and more confident peers – the potential bullies – to bring down and destroy the ‘outsider’. Weaker individuals are more easily threatened and they feel a greater need than stronger individuals to strengthen the group. When the weaker individual in a group feels threatened, their amygdala is triggered and they immediately go into ‘fight’ mode because they wish to reassure themselves that they have the powerful personality of the bully to back up their position. Sadly, the target often goes into ‘flight’ mode and the sidekicks and the bullies thereby enjoy a quick shot of power and so they often return to the target in a bid to repeat the experience.

There is some good news, though, because further research on the brain shows us that humans have further developed their response to the amygdala with the prefrontal lobes behind the forehead. This gives humans the opportunity to attempt to persuade, placate or outwit their adversary and so emotionally intelligent people can often talk their way out of a bullying situation as they can more easily understand what is driving the situation and can figure out what they need to say to placate them. It is this ability to box clever that can help the target of bullies to move beyond bullying to a more secure position in the social group.

The difference between bullying and conflict

There is a growing tendency for people to cry ‘bully’ when in reality no bullying is taking place. Many people feel that the word ‘bullying’ has been hijacked and its meaning has been abused and diluted through flippant overuse. This linguistic creep means that it is not always clear just who the bully is and who the victim is; and so everyone loses when the word ‘bully’ is misused and overused. It skews the general public’s view of bullies and creates feelings of outrage and sympathy on behalf of wrongly accused so-called bullies.

Lack of knowledge about what bullying actually is further conflates the issue of bullying. Both my children are prone to shout ‘bully’ whenever they get into conflict. They are children of their generation and so it has been drilled into them at school, at their activities and from everyone else that bullying is bad and it is a quick method to get the full attention of the supervising adult. And so randomly, from the back of the car, these squabbling siblings suddenly shout ‘You’re a bully!’ in a bid for Mammy’s attention.

Bullying is meanness from someone with more power than you that is repeated over a period of time. Teasing isn’t bullying; taunting isn’t even bullying – although it’s unkind and it can be traumatising, the taunting would have to be repeated over a period of time by someone with more power to be described as bullying. Having a sustained conflict or disagreement with someone also isn’t bullying. Neither can being mean or unkind be classed as bullying, unless it happens repeatedly and the perpetrator has more power than the target.

Gina came to me for counselling as she had been very distressed about accusations of bullying from another student in her class. Gina came from a politically involved family and she loved debating thorny issues with anyone who would engage. An atheist and a scientist, Gina had become inflamed by the fact that one of her schoolmates, Pauline, was a committed Catholic who also held Creationist views. The situation was further complicated because Gina and Pauline were also rivals for the pole position in the class. Gina became like a rabid bloodhound baiting Pauline into a discussion about evolution and then blinding her with scientific theory. Gina enjoyed every moment of it. Pauline dreaded it and began to pretend to be sick so she could stay off school.

Pauline’s mother called the principal and demanded that something be done about Gina’s bullying. Gina was hauled into the principal’s office and was horrified to learn that she was being accused of being a bully – Gina thought she was engaging in intellectual discourse! Although willing to attend counselling, Gina felt bewildered by this turn of events and was relieved when I explained to her that if a person is willing to engage in reasoned debate without tipping over the line into name-calling or silencing the other person then they are generally not bullying – they may merely be impassioned. Some people are very opinionated and they enjoy challenging and debating issues with others. Some people don’t like this type of person; they find them confrontational and tiresome and so they should probably keep their distance from them. Then again, other people don’t like the type of person who keeps their opinions to themselves and refuses to engage in debate.

Tackling gossip and teasing

If your child comes to you worried about gossip or teasing that is going on in their lives, first of all you need to take the child seriously. Don’t dismiss, downplay or use humour in this deeply vulnerable moment.

Listen carefully to your child. Ask open-ended questions so that you can ascertain exactly how your child is feeling, e.g. ‘Am I right in thinking that you are particularly annoyed because they are doing all this behind your back?’ Be prepared for your child to become irritated when you don’t get it quickly enough; apologise and plod on haplessly anyway until you completely understand the situation.

Empathise with your child. Put yourself in their shoes for a moment. This might be very painful for you and so many parents tend to brush over this bit but it will give you a deeper understanding of their pain and you won’t be so inclined to minimise the situation in the future. You can empathise with your child by using the exact words that they use; if the teenager says it is ‘horrendous’ then make sure when you are clarifying that you use the word ‘horrendous’ instead of similar words such as ‘horrible’ or ‘disastrous’. By using the words that they use to describe their emotions you are learning to see it from their perspective.

Be prepared to spend a lot of time discussing the pros and cons of the next step. This can be discussed with the child, but perhaps not only with the child and not always in front of the child. Forums such as mumsnet.com can give perspective, as closer friends on your local social media groups can tend towards hysteria, righteousness and an unhealthy desire to be involved in a bit of drama.

Over-protected ‘cotton wool kids’

In this era of over-protected ‘cotton wool kids’, many children are so accustomed to looking to the nearest adult to rescue them that when they reach their teen years they haven’t yet developed any ability to look after themselves. In my work as a psychotherapist I often meet these innocent and much-loved kids who haven’t yet had the opportunity to learn resilience, self-protection or well-developed social skills.

My previous book Cotton Wool Kids explores how many kids today haven’t had the opportunity to learn how to handle problems, big or small, on their own and so they often ask their parents or their teacher to help when they are being bullied – with the full expectation that the adults will save the day as they have always done before. It can be very disconcerting for these children when they enter secondary school and they realise that it is suddenly no longer appropriate or possible for the grown-ups to step in and fight their battles – indeed, many of them feel like they have fallen from a cliff without a safety net when parents and teachers offer strategies that will help them but ultimately expect the child to sort it out themselves.

But these kids can’t sort it out themselves – they haven’t had any practice at it yet.

These tweens and teens have no experience or know-how when it comes to conflict and so, sometimes, conflict that can and should be managed easily can tip into bullying as the offender realises that the target runs to Mammy every time they are upset. The gaucheness of the cotton wool kid then becomes another reason to tease the child. The target might wrongly believe that their parents or teachers will stop the bullying and they often don’t understand that their power really lies within. If parents don’t teach their children how to handle conflict or difficult people then the child won’t be fully equipped to become a healthy, functioning adult when they leave their teen years.

When Rónán, 13, was in primary school, he could easily cope with any negativity he received from his schoolmates; he simply went up and told the teacher and the teacher generally ensured that everyone would play nicely. However, this system didn’t work so well when Rónán moved from primary to secondary school.

At the start of first year, a boy called Josh kept teasing Rónán about his hairstyle and so Rónán (instead of dealing directly with Josh and telling him to lay off) did what he had been taught to do –– he requested help from the supervising adults. But the teasing was mild and the teacher advised Rónán to handle it himself.

Josh and his friends soon realised that Rónán had ‘snitched’ on him and it hadn’t worked. As a direct result of this, they upped the ante. They began calling him ‘rat’ whenever he walked by. Rónán refused to look at them and stared down at the ground whenever they taunted him. Josh and his friends thought that this was hilarious and began doing all sorts of things in a bid to make Rónán react. Rónán, not knowing what else to do, still didn’t react –– never realising that this had become part of the game for Josh and his group.

At a loss, Rónán asked his mother to help. His mother duly contacted the school and was told that Rónán needed to learn to fight his own battles. Eventually, Rónán ended up in my office for counselling and he told me the whole story. What had started as a very small event had continued unchecked until Rónán’s life in his new school was being ruined by mindless bullying. Rónán and I worked together and, over time, Rónán learned to handle the bullies with forethought and emotional intelligence (see Chapters 8 & 9). Josh and his pals became less entertained by Rónán as he was no longer responding in a way that made them laugh and so they moved on to other means of entertainment.

One day, as Rónán and I were reflecting on the damage caused to his psyche by the months of bullying in his first year of secondary school, Rónán suddenly exploded, ‘God, I wish I had just handled it right the first couple of times Josh slagged me! I needlessly endured months of misery because I just didn’t know how to respond!’

Why we have become so sensitive to imagined hurts? Why do we choose to dwell on one negative remark and tend to cast aside the positive remarks? This book aims to give a comprehensive view on bullying and so the increase of inappropriate accusations of bullying and the culture of offence needs to be thoroughly explored.

Many of us, in certain circumstances, can end up playing the victim. Generally, we do this in a bid to have more control of a situation or to try to cope with a situation. If this doesn’t work out successfully for us then we may learn more helpful coping strategies. However, if playing the victim does bring about the desired outcome, many people can fall into this way of behaving without knowing any better. We will look at this in more detail in Chapter 4.

A ‘cry-bully’ is the oxymoronic name for people who play the victim in a bid to dominate any given situation. The controversial journalist Julie Burchill succinctly describes the cry-bully as ‘a hideous hybrid of victim and victor, weeper and walloper’.6 In the old days the bully kicked sand in the face of the victim and we all rooted for the victim to triumph. But it’s all much more complicated than that now, and nowadays when bullying is mentioned, wary caution is the most common reaction as people try to figure out the full story. This became very evident to me when I told colleagues that I was writing a book about bullying and many people contacted me with the express request that I include the rising issue of inappropriate accusations of bullying.

I often give talks in schools and organisations around the country and just recently I was asked to give a talk in a certain school where there was a serious problem with bullying. I was advised beforehand that a child – let’s call her ‘Niamh’ – was bullying many of her peers and it was for this reason that I was drafted in. I had barely put up my first slide when the first sob came from Niamh. To my utter amazement, Niamh’s sobs continued unabated throughout the talk as she explained loudly at every opportunity how she was a victim of bullying. The nonplussed hostility from everyone else in the room demonstrated clearly what Niamh’s peers thought of her crocodile tears, and yet Niamh was obviously in great anguish and evidently thought of herself as a victim of bullying.

Sadly, because bullying gets so much instant attention, some bullies pose as victims of bullying in a bid to gain power and control over a situation. In the film Mean Girls, the character of Regina George goes a bit mad when she loses her power over everyone and poses as a victim of bullying to her school principal. Regina shows the principal a book that she herself had made, filled with pages of all sorts of terrible things about everyone in the school – including herself. Regina does this to gain control over the situation by posing as a victim of bullying. Mad perhaps, but strangely common.

2

Complicated relationships

Frenemies and power plays

‘Wishing to be friends is quick work, but friendship is a slow-ripening fruit.’

Aristotle

Children are, of course, new to the game of life, and they tend to make friends quickly, easily and naively. This is all well and good when they are very young; however, as children grow older (usually from about nine years onwards), they begin to discriminate between their friends.

This can become a very troublesome aspect of childhood for the type of child who finds it difficult to understand the complexities and subtleties of the social world. And so, some kids – kids who tend to fall in and out of friendships, kids who have difficulties making or keeping friends and kids who frequently find themselves enmeshed in complicated power plays – often need extra help and support with maintaining positive relationships. Although parents can’t make their children suddenly become popular, they can build and develop their child’s emotional intelligence so that the child becomes more aware and better able to anticipate the impact of certain behaviour. Simply by learning better social skills, these kids will find their social life easier and more manageable.

Psychosocial stages and personality types

It is when tweens and teenagers begin to form their identities and become more socially sensitive that they often tend to become incredibly conscious of the social standing of their friends. They become afraid to be friends with someone who isn’t pre-approved by the pack because in doing so they might inadvertently lower their own stock. It is during the socially volatile early teen years that kids most desperately want to be part of a tribe and many of them will do almost anything to fit into whatever random group they find themselves in.

Erik Erikson’s world-renowned psychosocial stages of human development show us why it is that teenagers become inordinately involved with their peers in secondary school. From the age of 12 to 18 normally developing humans psychologically begin to move away from their families and begin to figure out who they really are. As teenagers are finding their identity, their peers begin to replace their family as their chief influence. This is why the intense focus on social standing is a natural part of the teenage years, but it is important to help the child keep perspective as it can be a very cruel time for everyone involved. Many teachers report that 2nd year in secondary school is emotional carnage as the students become almost obsessed with their social status. Fortunately, this all calms down by the time they have grown up enough to go on to third level (the bad news is that by then they will become obsessed with finding ‘the one’). See the table on Erikson’s psychosocial stages for more details.7

Stage

Psychosocial Crisis

Basic Virtue

Age

1

Trust vs. mistrust

Hope

Infancy (0 to 1½)

2

Autonomy vs. shame

Will

Early childhood (1½ to 3)

3

Initiative vs. guilt

Purpose

Play age (3 to 5)

4

Industry vs. inferiority

Competency

School age (5 to 12)

5

Ego identity vs. role confusion

Fidelity

Adolescence (12 to 18)

6

Intimacy vs. isolation

Love

Young adulthood (18 to 40)

7

Generativity vs. stagnation

Care

Adulthood (40 to 65)

8

Ego integrity vs. despair

Wisdom

Maturity (65+)

Some children, especially those who haven’t formed a strong identity, can yield to whatever way the wind blows and might more easily get along with everyone. Other children form a strong identity at a young age and so they can find it harder to mix socially with different personality types. It is often the children with stronger personalities who find their schooldays that bit harder as they find it more difficult to roll with the punches – they can’t just put aside their likes and dislikes without rebelling on some level.

Some children are naturally easy-going and so will always get along with the crowd. Many parents dearly wish that their children were more easy-going – not selfishly, but because many parents remember with horror those who struggled socially during their own teenage years, and so they naturally hope that their children are well-liked, find friends easily and don’t have to face any of that cruelty. This is why being easy-going is often considered a very desirable trait to have; it is also much easier on a day-to-day basis to live with someone who is easy-going.

Well, if all your children are easy-going and find it easy to make friends, you are unlikely to be reading this book and so we can safely assume that your life is a bit more complicated than that. However, it is important to point out (albeit this is coming from a person who isn’t particularly easy-going herself) that although being easy-going is handy when you’re a teenager and going through the psychosocial stage where popularity is everything, as we grow up being easy-going is not necessarily the very best thing to be.

I know two children very well. One is intense, loyal, passionate and volatile; the other is easy-going, flexible, likeable and calm. All of these traits have worth and value; however, most adults prefer the easy-going child. (Well, they would, wouldn't they?) I am an intense person and I would just like to take this opportunity to give a shout out for the more ‘challenging’ (or ‘difficult’) among us.

Easy-going people tend not to challenge people or the status quo and they prefer to conform and comply; this is why it is so much easier for an adult to be in the company of an easy-going child. However, on the other hand, an easy-going person is less likely to do anything significantly useful or worthwhile – they often don’t have the commitment, passion or the dogged determination that is generally required for a person to achieve the extraordinary. Instead, easy-going people tend to be a force for good in another way because their presence often impacts the world in a positive manner, and yet the passionate people can also be a force for good – for it is the intense and passionate people who are motivated to commit to changing the world. If we look to history (or even look among our own family) we soon see that we need intense, loyal, passionate and volatile people just as much as we need calm, funny and easy-going people and so, thankfully, all God’s creatures have a place in the choir!

Popularity and the social hierarchy

Most children, by the time they are 11 years old, say they are part of a friendship group or clique and an interesting hierarchy among children in a classroom setting has been identified.8

Approximately one-third of students are in the dominant popular group. This group or clique may (depending on the environment) engage in a lot of nasty political behaviour so as to maintain or enhance their social status.

About one-tenth of children are in the ‘wannabe’ group. These kids hang around the edges of the popular group hoping desperately to get the nod so they can join the cool clique. They usually get enough crumbs of approval from the head table to keep them hooked, but they rarely gain full acceptance.

About one-half of students occupy the middle ground. This involves smaller, independent friendship groups, where the emphasis is on being loyal, kind and supportive of each other. These kids often dislike the popular kids, because they see them as unfriendly and standoffish, but they also look down on less popular kids. It is these kids that the involved parent of an unhappily socialised child needs to try to identify and work towards – but remember, your child might be so dazzled by the ‘cool kids’ that they can be dismissive of this crowd.

About one-tenth of the students are socially isolated from every group. These children are most at risk for being targets of bullying.