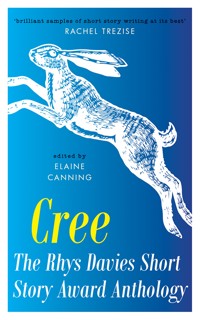

Cree E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A collection of new contemporary short stories by Welsh writers, representing the winners of the 2022 Rhys Davies Short Story Competition. Family connections, unconventional friendships, love and loss: the twelve stories in this collection of new contemporary fiction by the winners of the 2022 Rhys Davies Short Story Competition present characters seeking solace, self-discovery and self-fulfilment as they navigate familiar and unfamiliar territory. Two sisters search for the last available Christmas tree while coming to terms with their mother's death; a stammering teen hitches a lift with a Welsh Elvis; a man participates in his 'endgame'; and a teacher and pupil create their very own time machine. From hillside encounters to conversations in homes, shops and on the street, these are stories about people and place, about relationships and revelations, peppered with memories and re-imaginings. These are stories where some voices are silenced and others get to sing. The Rhys Davies Short Story Competition recognises the very best unpublished short stories in English in any style by writers aged 18 or over who were born in Wales, have lived in Wales for two years or more, or are currently living in Wales. Originally established in 1991, Parthian is delighted to publish the 2022 winning stories on behalf of the Rhys Davies Trust and in association with Swansea University's Cultural Institute. Previous winners of the prize have included Leonora Brito, Lewis Davies, Tristan Hughes and Kate Hamer. Authors in this anthology: Lindsay Gillespie, Bethan James, Meredith Miller, Laura Morris, Jonathan Page, Matthew G. Rees, Eryl Samuel, Matthew David Scott, Carys Shannon, Anthony Shapland, Satterday Shaw, and Daniel Patrick Luke Strogen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

CREE

The Rhys Davies Short Story Award Anthology

Edited by Elaine Canning Selected and Introduced by Rachel Trezise

Contents

Introduction

Rachel Trezise

When I met my husband, from Clydach Vale, (at the other end of the Rhondda Valley to my own hometown, Treorchy) in January 2000, I noticed a blue plaque on the front of a house a little further along his street, an English Heritage commemoration to writer Rhys Davies who grew up in the greengrocer shop run by his father in the village, and after whom this competition is named. I have two very significant things in common with Rhys Davies. Firstly, we’re both writers noted for our short stories despite also being novelists and playwrights, and secondly of course we both grew up in and chose to set much of our work in the Rhondda, a former coal mining area nestled in the centre of the south Wales valleys north of Cardiff, most famous for male voice choirs and rugby players.

I think the people of the Rhondda lend themselves particularly well to characters in literary and dramatic works, short stories in particular. As Irish short story writer Frank O’Connor explained in his study on the short story form, ‘The Lonely Voice’: ‘Always in the short story there is this sense of outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society hoping to escape from submerged population groups. As a result there is in the short story at its most characteristic something we do not often find in the novel – an intense 2awareness of human loneliness.’ The Rhondda Valley at the time of Davies’s youth was nothing if not a ‘submerged population’, the Depression of 1920 having finally reversed an industrial growth which had been in full flow for a hundred-and-fifty years. The south Wales coalfield, more dependent on exports than any other British mining area, was the worst hit.

Davies was apparently himself an ‘outsider’, quitter of school and chapel and a dandy who wore spats and carried a cane, who ate cake from his father’s shop amid hunger-inducing mining strikes, a gay man living in the macho confines of coal country at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. Two of the stories in this anthology address the subject of being born homosexual in a loftily-heterosexual world. In ‘Foolscap’ Anthony Shapland fabricates a meeting between almost-strangers on a hill above the town; ‘a play track for stunt bikes, a den, a place to get lost in, to disappear in, alongside siblings. Or away from them.’ The rendezvous is hastily planned between characters simply called ‘B’ and ‘M’. B knows how to be with other men; his brothers, his friends, his father, but now there’s a new relationship to navigate, and a recognition of something he can’t name. In ‘Ghost Songs, 1985’ Eryl Samuel employs pop culture to spell out the secret. Lloyd, bored on the picket line, snatches a listen to the Walkman he recently confiscated from his moping son: ‘He pulls up his collar and strains to hear the lyrics, but all he can hear is someone repetitively screeching, cryboy,cryboy,cry. It’s not Quo but at least it has an up-tempo beat…’

To my mind, Davies’s finest skill was developing distinctive and believable characters, especially female characters, perhaps by closely observing women from his village in his father’s grocery shop. Here, Matthew David Scott has written convincingly from the perspective of Jen, a record shop 3saleswoman striving to keep ends meeting in ‘An Intervention’. Daniel Patrick Strogen has created the wonderfully complex and straight-talking Hefina, looking back on her younger life in ‘Cracked/Duck’. And in ‘Splott Elvis and the Sundance Kid’, Lindsay Gillespie has firmly established stammering runaway, Stu, both poignant and funny, and brilliant company. Much like in Davies’s own work, the opposing themes of exile and belonging crop up in the anthology again and again, perhaps because south Wales, the valleys in particular, where most of these stories are set, has traditionally been the kind of place habitually left but very often returned to. Linette in Meredith Miller’s ‘Close in Time, Space or Order’ comes back to Wales to look for her mother after decades camping on farms in Europe, only to find sleeping butterflies and newsletters from Greenham Common. ‘He only said that because he needed her there,’ Linette says of an old neighbour when he asks her not to leave again. ‘They always need you in places like this. They want to watch you rise and fall.’ In Matthew G. Rees’s brilliant ‘Endgame’ a retired rugby ref, ‘coastal belt now’, returns to the valleys to officiate one last match. Suspecting someone from the club has poisoned his half-time tea, he paranoidly imagines their reasoning: ‘Seen where this bastard’s from? We’ll teach him. Comin’ up yer… bloody G-and-T-er!’ But elsewhere he concedes: ‘There was only oneplace on this earth where you were ‘from’… the place that, when asked by others, you – or at least they – spoke of as your ‘home’ – the place where you were born… where you were schooled… the land – or that scarred, slagged patch of it – that was the land of your fathers and mothers. Thatwas your home – no denying it, no shaking it off.’

There are also, however, other, more universal themes and topics. Grief, after the death of a family member as in Carys Shannon’s ‘Angel Face’ and Bethan James’s ‘The Space 4Between Pauses’, or for part of your own self as in Satterday Shaw’s heartbreaking ‘My How To Guide’ is impossible to avoid in literature and indeed life. But thankfully so is friendship, my favourite of all the themes in Laura Morris’s winning story ‘Cree’. It’s here we watch a tired schoolteacher, Mrs Williams, develop an unusual camaraderie with one of her young pupils, Ben, who will remain her sole confidante when everything else in her life goes awry. The anthology is sometimes dark and emotional but always witty and acutely observed, the twelve shortlisted stories examining Welsh life, past and present, the strange games people play and the coping mechanisms they employ. A vivid portrait of the human condition in so very few words.

Cree

Laura Morris

Parents gather at the edge of the playground, not sure how close they should get to us – the teachers – as if we are strange beings from another time and place. Fathers send their children from the railings to the middle of the playground, ready to line up. Mothers get a little closer, teary, seeking reassurance from the eyes of others. A boy in Year 3, who reminds me of my Rhys, runs around the playground chasing the girls.

‘I’m on cree-ee. You can’t tag me,’ one shouts.

Cree – the pre-determined safe place; the place where you can’t get tagged – is, today, according to the children, the small patch of tarmac on the playground that’s slightly lighter than the rest. When you are on cree, no one can get you. You are safe. You are home.

Year 6 stand on benches, carried out to the playground from the hall. The photographer’s assistant shuffles and draws children, while the teachers take the seats at the front. John, the headmaster, surveys us, then joins the photograph. Deborah, the deputy, sits by his side.

‘Knees together, ladies,’ says the photographer.

Obediently, we snap our legs closed. The men are asked to sit with their legs apart, to make fists and place them on their 6knees. We smile, in unison say, ‘Caerphilly cheese,’ but in my head, I’m saying just take the bloody picture.

Later, I hand out exercise books, and tell the children to turn to the first page.

‘Feel that paper with your hands,’ I say. ‘It’s lovely and smooth, isn’t it? I always think a fresh page is like a fresh start.’

The children look up at me. Waiting.

‘Our theme for this year, Year 6, is The Future. We will be looking ahead to the Year 2000 and beyond – considering issues like science, technology, the environment, travel, and of course, any ideas you may have. Copy the date down neatly,’ I say, tapping on September, the fourth with my whiteboard pen. ‘Notice how we spell fourth. Remember the ‘u’.’

There’s too much noise coming from the classroom opposite: raised voices, laughter, the sound of chairs scraping across linoleum. I put my head around the door to find out what is going on. Sheets of newspaper, pots of glue and packets of straws are strewn over the tables.

‘We are building bridges,’ Emily, the new teacher, giggles. ‘Literally and metaphorically.’

I smile, nod, and close the door.

‘What are they doing?’ asks Charlotte Evans, now out of her seat.

‘Shhh.’ I hold my finger to my lips.

The familiar feeling of pain behind my eyes.

John has set up a flipchart in front of the stage. He invites us to sit in a half circle, to peel a pink Post-it from the pack.

‘What are we meant to be doing?’ I ask Mari.

‘We are writing down key words for the school’s new mission statement.’

‘Why can’t we just say them out loud?’7

‘I think he’s been on another course,’ Mari whispers.

He invites us, one by one, to place our Post-its on the flipchart, to explain our chosen word to the room.

‘Freedom,’ I say. ‘I don’t think I need to explain that, do I?’

Emily’s word is ‘progress’.

John’s word is ‘standards’.

I have misunderstood the task.

‘Deborah will gather all of the Post-its, collate the information, and get it typed up,’ says John.

Deborah clicks her pen, writes in her new notebook.

‘Number 2 on the agenda: the Christmas concert… I’ve been thinking,’ John says, ‘it’s time for something new, something modern.’

‘But… we always do the nativity… always,’ I say, aware that I’m interrupting, aware that my voice is higher than it usually is.

‘Last year, when training, I…’ Emily begins.

‘It’s time for a change, Meryl. If you keep doing what you’ve always done, you’ll keep getting what you’ve always got.’

‘But the parents enjoy it,’ I say.

‘I’m sure the parents are just as bored as we are, Meryl.’ He holds his pale hand to his mouth, performs an exaggerated yawn.

‘But it’s what Christmas is!’

‘Deborah, if you could oversee the concert, please?’

Deborah nods, makes a mm-hmnoise, and writes down John’s instruction.

‘Number 3 on the agenda: the inspection. We haven’t had the exact dates yet, but we think it will be at the beginning of the spring term. Deborah has been in touch with a school in Gwynedd – inspected last March – and has learned that 8inspectors like to see original takes on theme work. Our themes are: Year 3 – Wales, Year 4 – Heroes and Villains, Year 5 – Animals, Year 6 – The Future. Creative ideas, please?’

‘I thought we could dress up as dragons,’ says Mel, ‘for Wales.’

‘Excellent,’ says Deborah, repeating Mel’s words slowly, before writing them down.

‘What about Year 6?’ I ask. ‘The Future? They are a bit too old to dress up?’

‘You could build a time machine,’ suggests Emily.

‘Yes,’ everyone agrees. ‘Great idea, Emily.’

I say nothing. I’m thinking of the mess, the time that constructing such a thing will take. But later, driving home, queueing at the Piccadilly lights, I realise that it is a good idea; it could elicit some wonderful writing from the children.

Rhys’s halls are clean and modern, not like the digs I had in my first year at Aber. An en suite! I nod politely at other parents as we pass on the stairs with boxes. So much stuff piled up in the boot, but it doesn’t look like a lot once we’ve unpacked and arranged his new life on the narrow shelves above the desk.

‘If you get homesick, I will come to get you. I will pick you up,’ I say. ‘You know that.’

‘He can get the Trawscambria,’ says Bill.

‘I will be fine, Mam.’

I want us to walk along the promenade, like Bill and I used to, but Rhys’s new flatmates have asked him to drinks, and Bill isn’t keen – ‘The clouds are thick. Full of something,’ he says, staring up at the darkening sky.

Bill drives his route home – short cuts, weak bridges, single lanes. The rain is heavy on the windscreen, becoming sleet. It’s 9not at all like the October Dad drove me to Aber. Dry. Cool. Still. 1965. A blue and green checked coat, a knotted navy scarf flung freely over my shoulder.

Bill is singing. He’s tapping out a rhythm on his knee.

I am shrieking. I am reaching for Bill’s arm, telling him to brake.

There is a lamb lying in the middle of the road, a ewe nursing it.

‘Do something!’

‘Like what?’

The lamb is bleeding from its side, and the ewe is licking it. I try to guide the ewe to the side of the road, but it’s bleating protectively, and won’t leave its child. I pull up the hood of my raincoat to stop the rain getting in, but the wind keeps tugging it back down.

‘Come on, Meryl. Leave it.’

I run around the side of the car, and take out the picnic blanket from the boot. I am trying to say, ‘We can’t leave it here,’ but my throat can only make noises, noises that come from the deep of my belly.

I wrap the blanket around the lamb, and Bill helps me carry it to the side of the road. Neither of us speaks for the rest of the journey home, but he must know that I’m crying. I sound like an animal, I think. I sound like the ewe.

The children and I compile a list: broken watches and clocks, buttons, yogurt pots, tins, egg cartons, bubble wrap. We plan different designs for the time machine, and at the end of the session the new child, Ben, brings me a wonderfully ambitious diagram – neatly labelled. I’m not sure the end result will meet his vision, but I will endeavour.

I begin the work of assembling a frame out of cardboard 10boxes and old wood. I use the glue gun to fix all of the sections together; then, putting down newspaper to catch the drips, I promise the children I will paint it during dinner time.

They unpack their sandwich boxes, collect coats from their hooks, but Ben stays behind.

‘May I help you paint, Mrs Williams?’ he asks.

‘Of course,’ I say, ‘but wouldn’t you rather play outside? It’s a lovely autumnal day.’

‘I would rather be doing this.’

I have noticed that when the other boys are playing rugby, Ben sits on the steps to the portacabin, reading.

‘Well in that case, I had better find you a brush.’

Over dinner, Ben tells me about time dimensions. I listen patiently and never once say that these things he is explaining are not possible.

‘And how do you know all of this?’

‘I have some of the old DoctorWhoannuals and my mother finds me the videos in charity shops.’

‘Who is your favourite doctor?’ I ask.

‘John Pertwee, I think.’

I nod. I know who that one is.

‘I’m going to eat my lunch now, Mrs Williams,’ he says.

‘Of course, Ben.’

He removes clingfilmed sandwiches from his tin; they are crustless, cut into perfect squares. He nibbles around the edges, until the square gets smaller and smaller, then eats his grapes, then the chopped apple, then his chocolate bar, splitting it into pieces first. He takes a sip of his drink.

‘I don’t like mixing foods in my mouth, Mrs Williams.’

‘Neither do I, Ben, neither do I. Do you know what? You and I are exactlythe same,’ I say, sitting back at my desk, cleaning my glasses with the corner of my skirt.11

‘You may not know this about me, but I sometimes wear glasses,’ Ben says.

‘Oh.’

‘But my father wears contact lenses, Mrs Williams. Have you ever tried them? I think you should – bring out your eyes a bit more. I sometimes feel they are hidden beneath your glasses.’

The optician’s face is so close to mine that I can smell his skin. He asks me to rest my face in various contraptions, shines lights in front of my eyes. They unsettle me, these tests. Any sort of test. Afterwards, he leads me out of the room and sits me at a table on the shop floor. I watch him open a packet of lenses, and fish one out of its solution with his fingers.

He shows me how to hold my eye open with one hand, then how to pick up the lens with the other.

I get the lens quite close to my eyeball, but my eyelid is twitching.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘It’s difficult.’

‘Try the other first,’ he says. ‘You might find it easier.’ He glances at his watch.

‘I have taken up too much of your time,’ I say.

At home, I ask Bill if he notices anything different about me. He moves his tongue around his mouth, as if dislodging spinach from between teeth.

‘New scarf?’

‘I have contact lenses,’ I say. ‘I’m not wearing glasses.’

‘Why?’

‘Well…’ I begin. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

That evening, I hear him on the phone in the spare room, where he now sleeps. His voice is low and soft, and I know he’s talking to her.12

Ben is standing outside the classroom, holding a Batman walkie-talkie. I am inside the time machine, holding its twin.

‘Mrs Williams, can you hear me? Over.’

‘I can hear you,’ I say, adjusting Robin’s aerial.

‘I have been thinking… we need a control panel, otherwise how will the time machine work? Over.’

‘Yes. Good idea.’

‘Where would you go, Mrs Williams, if you could go anywhere? Over.’

‘Now, I know that we are learning about the future, Ben, but I would go back in time, back to 1965,’ I say. ‘October 20th, 1965.’

‘You need to say “over” when you have finished, Mrs

Williams.’

‘Sorry, Ben, of course. I’m not very good at this, am I? Over.’

‘She keeps thinking she has told me things when she hasn’t,’ Dad tells me. ‘Like the dentist this morning. Luckily, Mr Thomas understood, and fitted her in when we got there late.’

‘I thought you were marking things on the calendar.’

‘I try,’ he says, ‘but I forget too.’

Mam’s in the living room, sitting in her armchair. There’s a hot water bottle behind her, and weak tea trembling in the bone china cup.

‘Rhys not with you?’ she asks.

‘He’s at university, Mam.’

‘Ah, yes, Swansea.’

‘No, Mam. Aberystwyth. Remember?’

‘Ah. Bet you regret not having another now? I told you that you’d be lonely.’

Back then, I kept a diary, and on October 21st, 1965, I wrote one 13word, and underlined it: Bill. Nothing else, just his name. I never wrote in the diary again, and I never kept a diary again, not one like that, not one for feelings.

I know now that there could have been other men. I know now that I married the wrong man.

Ben is sitting inside the time machine on a piano stool I brought in from the garage.

‘Where will you go, Ben?’

‘To the future,’ he says.

‘What is it like there?’ I listen from outside.

‘I’m not there yet. I haven’t pressed the correct buttons.’

‘Sorry, Ben,’ I say. ‘Silly me.’

That evening, at home, he writes a story about warring robots, and when he shows me the following morning, I look past the violence of his drawings, and focus on the ambitious vocabulary he has used. I take his work to my next progress meeting with Deborah.

‘So,’ she begins, ‘who are your level 5s?’

‘Well, Ben definitely. I mean, he’s probably higher than a 5. I have been giving him books to read at home. He’s read Animal Farm, and he understands the political allegory.’

‘He can’t be higher than a 5?’

‘He is.’

‘It stops at a 5. He can’t be a 6 until secondary school.’

‘I think he is. If you look at the criteria, especially for writing, he is doing it all. Listen: You crouch behind a discarded shield,watchingthebattlefromsafety.Therobotsoldiersarequicker andstrongerthananyman,butdespitetheircomplexprogramming, theydon’thavethecompassionofahuman.You see how he’s used the second person here, and the present tense. I’ve not taught him those things. He’s just doing them.’14

‘Yes. That is quite good. You should do that task with the class during inspection week. That would really impress them.’

‘But he’s already written it?’

‘Yes, well he’s practised it. He could do it again. Remember we discussed this in the meeting last week, practising tasks.’

‘I’m not going to ask him to do it again.’

Deborah smiles at me.

‘How are you, Meryl?’

‘I’m okay, thank you.’

‘How are things? Youknow…’

‘Things?’

‘Yes, you know… things.’ Her charm bracelet jangles as she points her finger downwards. I think she is referring to my vagina, perhaps both of our vaginas, as if to say you’reawoman, andI’mawoman;weareinthistogether,youandme.

‘Are you referring to the menopause?’ I ask.

‘No, God no, but… I just wondered… Bill is doing well now, isn’t he? Lots of concerts. I saw he has a new car.’

‘Yes?’ One of the charms is a gold cat with two staring emerald eyes.

‘And I suppose you will be retiring soon. You know… I just wonder, do you need to work? Really?’

‘I am only fifty-five, Deborah.’

She looks at her nails, and I stare at the abstract painting hanging on her office wall. Thick pink brush strokes.

‘Meryl,’ she begins.

‘Yes.’

‘Do you think I could ever be headteacher?’

It is the Christmas concert. There are children wearing black leotards, leggings, and tunics made of Bacofoillurking around the school stage. They have been instructed to move slowly, to stretch 15out their arms, and to point, quite unsettlingly, into the audience. Swimming goggles sit uneasily on their heads, threatening to fall off with any sudden movement. At the end of the performance, I clap, and afterwards, when I’m pouring boiling water onto tea bags, and offering parents Co-opmince pies from a paper plate, I say how good their children were, how proud of them they should be. ‘Aliens! In the nativity?’ I say. ‘Whatever next?’

Later, while Bill is playing at a Christmas concert at St David’s Hall, I sit at the kitchen table, making additional features for the time machine – Ben’s suggestions. I draw a large circle on a sheet of grey cardboard. With a thick black pen, in capital letters I write PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE on the circle. I cut the shape of an arrow from black paper and place it in the centre of the circle. I then push a brass fastener through, allowing me to spin the arrow.

Rhys sits opposite me, home from university for the holidays. He fiddles with my papers, picks up a marker pen, puts it down again.

‘I need your help, Mam.’

‘What is it?’

‘I need to borrow money.’

‘What for?’

‘Not for me. Not really. It’s for a procedure. It was a one-night thing.’

The pen is in his hand again. He’s tapping it against the table.

‘Oh, Rhys.’

‘She wants it done as soon as possible. She doesn’t want to wait until after Christmas.’

‘No. I suppose she wouldn’t.’

‘Please don’t tell Dad.’

‘This is definitely what she wants too?’16

‘Yes.’

‘Then I will go to the bank on Monday.’

He kisses my cheek and says goodnight quietly. I stay at the table, spinning the arrow from past to present to future.

From past.

To present.

To future.

Boxing Day, I continue preparing lessons. I also have books to mark, comprehension tasks to assess. I move the tins of chocolate and shortbread out of the way, and spread my work across the kitchen table.

‘But it’s Christmas, Mer,’ says Bill.

‘I know, but I won’t fit everything in otherwise. There just isn’t the time.’

The telephone rings, and we both turn our heads, as if that will be enough to silence it; like a crying baby, it continues.

‘I’ll take it upstairs,’ Bill says, but it’s too late. I’ve got there first.

‘Hello.’

The other woman returns the receiver to its cradle.

‘But it’s Christmas, Bill,’ I say.

A new year. The tiny ghosts that leave my mouth remind me I am still breathing. I turn on the electric heater, remove my gloves and run my hand over the smooth and cool wood of the desk. Age spots on my hands now. I don’t remember the first wrinkle, the deepening of the lines on my forehead, the darkening of the shadows beneath my eyes, but there must have been a day when those things first appeared.

Inside the time machine, I use double-sided tape to fix Rhys’s old calculator to the control panel. Next to that I stick 17the Dairy Diary calendar the milkman left with our clotted cream and orange juice on Christmas Eve. I attach a piece of string to a small hook and tie the string around a pen.

‘We can circle the date we wish to travel to on the calendar,’ I explain to Ben.

‘A good idea,’ he says. ‘The time machine just needs one more thing.’

‘Yes?’

Ben unzips his rucksack, takes out a controller.

‘It’s from my Nintendo 64,’ he says, ‘I don’t need it anymore, Mrs Williams. I don’t play those sorts of games now.’

‘Oh Ben,’ I say, ‘only if you’re sure.’

‘I hope the inspectors like it, Mrs Williams.’ Carefully, so that I understand the power of the object, he hands me the controller.

‘Let’s fire up the glue gun!’

Afterwards we step back, regarding the time machine proudly.

‘It’s even better than I thought it would be,’ Ben says. ‘It’s almost… real.’

Phone the doctor

Pack a bag for Mam

Food shop for Dad

Flowers

‘We are running a race,’ John says to the children during assembly. ‘We can see the finish line ahead of us, but we aren’t there yet. It is important that we keep going and don’t dip until the very end… which will be…’ He pauses to flick through his notebook, looking for the inspection dates, ‘in approximately a fortnight’s time.’18

‘When’s this race Mr Jones keeps talking about? I think I might win,’ asks one of Emily’s.

‘What’s a fortnight?’ asks Ryan Thomas.

And all the time I am doing what they ask. We are practising the lessons and we are working on our spelling, writing better sentences, using connectives such as additionally and ontheotherhand.I sit with the weaker pupils, helping them write more accurately, dictating sentences to them, trying my hardest to get their work up to a level 4. I call them out one by one, listen to them read; I interview them, ask them their target levels, check that they know how to reach the next level. If they have been absent, then they stay in at break to catch up on the work they have missed. I trim their worksheets with the guillotine, I stick them to empty pages in their books. No gaps. There can’t be any gaps. I mark their work, commenting on the positives, writing out targets for improvement. Remembertouse anapostrophetoshowpossession.Writeinmoredetail,usingarange ofadjectives.6x9is54,7x9is63.Writetwomoresentencesabout Alun Michael.

The caretaker wheels a computer on a trolley into my classroom, and Ben sets it up. He shows me how to use the Internet, and tells me that I can ask Jeeves anything, and he will give me an answer. When the children have all gone home, into the white box next to the cartoon man wearing a pinstriped suit, I type: why do I feel so sad?

I arrange Mam’s flowers in a plain white vase, and she tells how, in the middle of the night, a woman at the other end of the ward calls out for her dead husband, Don. When I complain on her behalf, explain how Mam isn’t sleeping, the nurse tells me that I should have more compassion.

‘Imagine losing someone you love.’ 19

I imagine Bill lying in the middle of a country road, bleeding from his side.