6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

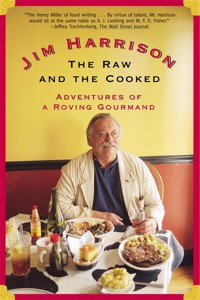

From her home on the California coast, Dalva hears the broad silence of the Nebraska prairie where she was born and longs for the son she gave up for adoption years before. Beautiful, fearless, tormented, at forty-five she has lived a life of lovers and adventures. Now, Dalva begins a journey that will take her back to the bosom of her family, to the half-Sioux lover of her youth and to a pioneering great-grandfather whose journals recount the bloody annihilation of the Plains Indians. On the way, she discovers a story that stretches from East to West, from the Civil War to Wounded Knee and Vietnam, and finds the balm to heal her wild and wounded soul. One of Harrison's most ambitious novels, Dalva explores an extraordinary family through the strong, engaging voice of an unforgettable woman, confirming Harrison as one of America's most memorable writers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise forDALVA

“Harrison uses his pen as a sword to right wrongs and settle scores . . . He takes bigger risks, letting go of old habits and surrendering to his own impassioned imagination.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Dalva is the most memorable character in all of Harrison’s work . . . probably the best prose writing of Harrison’s career.”

—Michigan: The Magazine of the Detroit News

“An exquisitely carved portrait.”

—Booklist

“If the reader is in any doubt at all during the opening pages of Jim Harrison’s 1988 novel Dalva as to whether they’re in the hands of a master craftsman then it is likely that these doubts will be put to bed . . . bold.”

—The Guardian

“Harrison . . . taps deep and true with this portrait of a family.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Entertaining, moving, and memorable . . . A cast of fascinating characters.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Harrison is an epic storyteller who deals in great vistas and vast distances.”

—New York Times Book Review

Also by Jim Harrison

FICTION

Wolf

Legends of the Fall

A Good Day to Die

Farmer

Warlock

Sundog

The Woman Lit by Fireflies

Julip

The Road Home

The Beast God Forgot

to Invent

True North

The Summer He Didn’t Die

Returning to Earth

The English Major

The Farmer’s Daughter

The Great Leader

The River Swimmer

Brown Dog

The Big Seven

The Ancient Minstrel

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

The Boy Who Ran to the Woods

POETRY

Plain Song

Locations

Outlyer and Ghazals

Letters to Yesenin

Returning to Earth

Selected & New Poems: 1961–1981

The Theory and Practice of Rivers and New Poems

After Ikkyū and Other Poems

The Shape of the Journey: New and Collected Poems

Braided Creek: A Conversation in Poetry, with Ted Kooser

Saving Daylight

In Search of Small Gods

Songs of Unreason

Dead Man’s Float

Complete Poems

ESSAYS

Just Before Dark: Collected Nonfiction

A Really Big Lunch

The Search for the Genuine

MEMOIR

Off to the Side

First published in the United States of America in 1988by E.P. Dutton/Seymour Lawrence

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2022by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Anna Productions, 1998

Excerpt from ‘Gacela of the Dark Death’ from Selected Poems by Federico García Lorca reprinted with permission. Copyright © 1955 by New Directions Publishing Corporation. Translated by Stephen Spender and G. L. Gill.

Lyric from ‘Heart of Gold’ by Neil Young used by permission.

Copyright © 1971 by Silver Fiddle. All rights reserved.

The moral right of Jim Harrison to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 430 5

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 876 1

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

forLinda King Harrison

CONTENTS

BOOK IDALVA

BOOK IIMICHAEL

BOOK IIIGOING HOME

We loved the earth but could not stay.

—LOREN EISELEY, “THE LITTLE TREASURES,”FROM AN OLD SAYING

BOOK I

DALVA

DALVA

Santa Monica—April 7, 1986, 4:00 A.M.

It was today—rather yesterday I think—that he told me it was important not to accept life as a brutal approximation. I said people don’t talk like that in this neighborhood. The fly that flies around me now in the dark is every fly that ever flew around me. I am on the couch, and when I awoke I thought I heard voices down by the river, a branch of the Niobrara River where with my sister I was baptized in a white dress. A boy yelled water snake and the preacher said get thee out of here snake and we all laughed. The snake drifted off in the current and the singing began. There are no rivers around here. Turning on the lamp above the couch I see he’s not here either. I can hear a car screeching on the coast highway even at this hour. There are always cars. The girl in the green bathing suit was hit seven times before the last car tossed her in a ditch. The autopsy said California speedball. Her suit was the color of winter wheat as I remember it, almost unnaturally green when the snow melted. It was so nice to have another color on earth other than brown grass, white snow, and black trees. Now between the cars I hear the ocean and the breeze lifts the pale-blue curtains with a sea odor the same as my skin. I’m quite happy though I may have to move after all these years, seven, actually. There is an abrasion, almost like a slight burn, from his mustache on my thigh. He asked if I wanted him to shave his mustache and I said, You’d be lost without it. That made him somewhat angry as if his vanity depended solely on something so fragile as a mustache. Of course he wasn’t listening to what I said but to all of his imagined resonances of what I said. When I laughed he became angrier and marched very dramatically around the room in his jockey shorts which were baggy in the rear. It was somehow warm and amusing but when he tried to grab my shoulders and shake me I told him to go back to his hotel and screw himself in front of the mirror until he felt he wanted to actually be with me again. So he left.

I thought I was writing this to my son in case I never get to see him, and in case something should happen to me, what I have written would tell him about his mother. My friend of last evening said, What if he isn’t worth the effort? That hadn’t occurred to me. I don’t know where he is and I have never seen him except for a moment after his birth. I can’t go to him because I’m not sure he knows I exist. Perhaps his adoptive parents never told him he was adopted. This is all less sentimental than it is unfinished business, a longing to know someone I have no particular right to know. But to know this son would complete the freedom men of my acquaintance seem to consider their birthright. And then, perhaps, my son is looking for me?

My name is Dalva. This is a rather strange name for someone from the upper Midwest but the explanation is simple. My father’s older brother was a victim of rebellion and adventure magazines, and was at odd times a merchant seaman, a prospector for gold and precious metals, and finally a geologist. Late in the Great Depression Paul was somewhere in the interior of Brazil from which he returned, after squandering most of his earnings in Rio, to the farm with some presents including a 78 rpm record of the sambas of that period. One of the sambas—in Portuguese of course—was “Estrella Dalva,” or “Morning Star,” and my parents loved the song. Naomi, my mother, told me that on warm summer evenings she and my father would put the record on the Victrola and dance up and down the big front porch of the farmhouse. My uncle Paul had taught them what he said was the samba before he disappeared again.

I just now thought that you can only meet a man at the level of his intentions. When my father and mother met and courted in the thirties the intentions were clear; they were both from fourth-generation farm families and the point was to marry and to continue traditions that had made their predecessors reasonably happy. This is not to say that they were simple-minded people in bib overalls and flour-sack gingham dress. There were several thousand acres of corn and wheat, Herefords, hogs, even a small slaughterhouse that at one time supplied prime beef to certain restaurants in faraway Chicago, Saint Louis, and Kansas City. From scrapbooks Mother has stored there are records of their trips to Chicago, New Orleans, Miami, and once to New York City which was my mother’s favorite. From World War II, when my father was a fighter pilot stationed in England, there is a photo of him with three gentlemen in front of the Hereford Registry in Hereford, England. He is in a jaunty hat and looks rather like one of the early photos of Howard Hughes. As Naomi would say, or prate, “Blood will tell,” and his unstable streak came out in his passion for airplanes. He was not called up but reenlisted for the Korean War because he wanted to learn to fly jet fighters. So between the ages of five and nine I knew my father, and I have still not exhausted the memories of those years. Beryl Markham said that when she stopped in Tunis on the way back to Europe in her small plane she met a prostitute who wanted to go home, but didn’t know where home was because she had been taken from her parents at age seven. She only knew that in her homeland there were tall trees and it was occasionally cold.

But I’m not one to live or subsist on memory, treating it as most do, the past and future as an encapsulated space or nodule we walked into, and then out of, rather than a continuum of the life we have already lived and will live. What was my father, really? Genes provide the fragilest of continuities.

On the farm we had a small plane called a Stinson Voyager. We’d go for Sunday rides when the weather was right. If I had been sick and out of school my father would tell me I’d feel better or be well by the time we landed and I believed him. I liked seeing the water birds on sandbars in the Missouri River, the way they flew up in clouds, then landed again when our immense shadow passed.

What upsets me is the terrifying and inconsolable bitterness of life; at close range in certain friends, and particularly in my sister who regards her mid-life as an arctic prison though she lives in Tucson. She’s never been given much to going out of doors. She lives in a fine home with a gray-and-white interior backed up against the Catalinas though she has never walked in these mountains. I thought of her yesterday at daylight when I walked the beach. Someone had spray-painted the word MENACE on the benches in Palisades Park, and on the steps going down to the beach, and somehow on a highway overpass. I stopped counting at twenty. Fortunately most lunatics don’t have the vigor of Charles Manson. I was interested in someone who spent a whole night spray-painting MENACE virtually in the face of the Pacific Ocean. Perhaps this vandal is the flip side of my sister. It is somewhat a mystery to me how the rich can feel so utterly fatigued and victimized. She drifts back and forth without specific density across the line of what she thinks is the unbearable present, but then she surprised me this March, during Easter, when my mother and I visited. I asked her how it was possible to live so thoroughly without nouns. At that moment she was waiting for the single drink she allowed herself each day at six.

“Why don’t you save up for six days and have seven drinks on Sunday?” Naomi asked. My mother does not stand back from any of the forms life takes. “You could have yourself a party.”

But my sister just sat there looking at the martini she would make last an hour, thinking about nouns as if on the lip of speaking the sentence my mother and I knew wouldn’t come. Ruth went to the piano and played a Mozart exercise my mother favored which also served as a signal for me to begin fixing dinner.

“Nouns are a burden to people these days,” Mother said. “Maybe they always were. Tell me about your latest fellow.”

“Michael is in the history department at Stanford. He heard about our journals years ago and last fall in Nebraska traced me back to Santa Monica. He’s about twenty pounds overweight and self-important. He tends to lecture at you and might talk about the history of food over dinner, the history of rain when it’s raining. He’s an expert at everything awful that ever happened in the history of the world. He’s brilliant without being very conscious. He’s a bad lover but I like being around him.”

“I think he sounds just wonderful. I’ve always preferred men to be a little goofy. If they’re trying to be men in the movies they get tiresome. I had this little fling with an ornithologist because I liked the way he climbed trees, waded up creeks, or into stock ponds to take photos. . . .” My mother is sixty-five.

We hadn’t heard the music stop and Ruth was right behind us at the kitchen door. Grandfather, who was half Oglala Sioux, called her Shy Bird Who Flies Away. Though Ruth is only one-eighth Sioux she had assumed certain Sioux qualities as she grew older, a kind of stillness that she forced to surround her.

“I think you’re right about nouns. Think of ‘car,’ ‘house,’ ‘piano,’ ‘food,’ ‘priest.’” We were prepared for the rush of words that came not more than once a day when we visited. “We have always been lapsed Methodists but I met this priest and we talk about love and death, art and God, which are all nouns of a sort I believe. He’s not a priest in a church but works with a charity for Indians and I know he sees me partly as a contributor. He loves to drive the car Ted sent me for Christmas.” Ted is her husband from whom she had been separated for fifteen years, the father of her son, a man who at twenty-eight discovered he was conclusively a homosexual. Ruth was born four years before Father died in Korea, losing the two central men in her life to quirks of history and sexuality. Ted and Ruth met at the Eastman School of Music where they intended to become famous in the music world, she as a pianist and he as a composer. Instead, she raised her child who apparently doesn’t care for her, blaming her specifically for the loss of his father. From my distance the arts always have seemed brutal, with the chances of the work being durable far less likely than had the aspirant tried to become an astronaut. And the failures I know are filled with an indefinable longing and melancholy for a flowering that was stunted in preparation for any number of reasons.

I was studying a Chinese recipe and ignoring Ruth until I heard the word “boyfriend.” It was akin to touching an electric fence as a child. I turned to notice that Mother was equally shocked, reaching nervously for the cigarettes she had abandoned years ago.

“Yes, I have a boyfriend. A lover. He’s my only lover in fifteen years. The priest is my lover. He’s really quite homely. He even told me that one reason he became a priest was because he was so homely. Singly, the features wouldn’t be that bad but arranged together as they are, the result is homeliness. Remember our cow dog, the mongrel we had when we were little called Sam who was so ugly? Anyway, Ted sent me some scarves from Paris, then an expensive car from a local dealer a few days later to go with the scarves. I had read about an Indian charity and checked it out with my neighbor who runs the newspaper. So I drove the car down there and met the priest. I gave him the signed title and the keys and asked him to call a cab for me, but he insisted on driving me home. I made him iced tea and he loved all the paintings and prints Ted and I had collected. Then he asked if I’d like to take a ride to the Papago Reservation the next day. He said the head of the diocese was in Los Angeles for a few days and he had never driven such a wonderful car. I was unsure and said I had never met any Indians in Arizona but I grew up around some of the Sioux and they frightened me. That’s because Granddad told me he was really a ghost who had never been born and would never die. I didn’t realize he probably was kidding. The priest wondered why I’d give a forty-thousand-dollar brand-new car to people who frightened me. I said Because I can read. Remember Grandpa’s Edward Curtis books? We had to wash our hands before we looked at them. So the next morning I made a picnic basket and he picked me up. He was originally from near Indianapolis and grew up loving fast cars as boys must do around there. It is a mystery how anyone could be that thrilled by a car. We took the long way, driving down toward Nogales, then across the Arivaca Canyon road through the Tumacacori Mountains. It’s a narrow dirt road with many curves and my priest loved the trip, though I thought he drove alarmingly. Nothing would have happened if there hadn’t been a sudden, brief thunderstorm. The clay on the road turned to butter and we were caught in a big dip in the mountain road. He said we would be OK when it dried out so we had a picnic in the car and drank a bottle of white wine. Then the rain stopped and the sun came out and it was hot and clear again. I got out of the car, crawled through a fence, and walked down a hill to a spring-fed stock pond. You know I’m not very enthused about nature so it was quite an adventure. The priest was frightened because there were cattle in the pines near the pond, one of them a bull, but I said that Hereford bulls aren’t dangerous so he joined me, he said it would take an hour for the road to dry off. I took off my shoes and waded in the pond, washing my face in the spring. I was terribly excited for no particular reason. Maybe I was feeling desire without admitting it. I don’t think so. It was just that I was doing something different. Then the priest said I should take a swim and that he had four sisters and bare skin didn’t bother him a bit. So I took off my skirt and blouse and dove in the water in my bra and panties. He stripped to his shorts and followed. It was absolutely perfect swimming though he was intensely nervous. I said that God was busy in cancer wards, Africa, and Central America, and wasn’t watching him. I got out to sun on a warm rock but he stayed in the water. Finally he said I guess I have an erection. I said You can’t stay in the water the rest of your life. He said Don’t look, and got out of the water and sat beside me staring straight ahead. I thought I am not going to let him get away so I stood up and took off my bra and panties hanging them on a bush to dry. Then I told him rather sternly to lay on his back on the grass and to close his eyes if he wished, he was shaking so hard I thought he’d fall apart like an old car. So I made love to him.”

Ruth began to laugh, then to cry and laugh at the same time. We hugged and patted her, praising her for breaking her drought of affection in such a unique way.

“A splendid story,” Naomi said.

“It’s a beautiful thing to happen. I’m proud of you,” I said. “I couldn’t have done a better job myself.”

Ruth thought this was very funny because she always has chided me by letter and on the phone for what she calls “promiscuity,” while I am lightly critical about her abstinence.

“The trouble was he wouldn’t stop crying and that reminded me of Ted and the night he told me about his problems, so I wanted to cry too but knew it was somehow unthinkable. He cried so hard I had to drive back to Tucson. He’d grind his teeth, say prayers in Latin, then weep again. He asked me to pray with him but I said I didn’t know how because, not being Catholic, I didn’t know the prayers. This at the same time shocked and calmed him. Why did I donate a car to the Catholics if I was a Protestant? I donated the car so it could be sold and the money would be used to help the Indians. But the Indians are Catholics he said. The Indians are Indians before they are Catholics I replied. He said he had felt his soul come out of him and into me and then he began crying again because he had betrayed Mary and ruined his life. Oh for God’s sake you fucking ninny, I yelled at him, and he became silent until we got to the house. For some reason I told him to come in and I’d give him a tranquilizer but all I had was aspirin which he took. Within minutes he said the tranquilizer was making him feel very strange. We had a drink and I made a snack tray with the pâté recipe you sent me, Dalva. He quoted me some poems and told me about the missions he had worked at in Brazil and Mexico. Now he was in his thirties and wanted to leave the country again. Brazil was difficult for him because you couldn’t avoid seeing all those beautiful bottoms in Rio. He poured himself another drink and said that one night he paid a girl to come to his hotel room so he could kiss her bottom. The tranquilizer is making me say this he said. So he kissed her bottom but she laughed because it tickled and that ruined everything. His eyes brimmed with tears again so I thought fast because I didn’t want to lose him. That’s what you want to do to me, isn’t it? Admit it. He nodded and stared out the window. I think that’s a good idea and that’s what you should do. He said it was still daylight and maybe it wouldn’t hurt because he had already sinned that day which wouldn’t be over until midnight. He’s quite a thinker. I stood up and started to take off my clothes. He got down on the floor. We really went to town all evening and I sent him home before midnight.”

Now we began laughing again, and Ruth decided to have another martini. I went back to the stove and began chopping garlic and fresh jalapeños.

“What in God’s name are you going to do about him?” Naomi asked. “Maybe you should look for a normal person now that you’ve got started again.”

“I never met a normal person and neither have you. I think he’s going to be sent away by his bishop. Naturally he confessed his sins though he waited two weeks until it became unbearable. You said Dad loved us but he went back to war anyway. There’s another funny part. The priest showed up rather early the next morning while I was weeding my herb garden. He had some books for me on Catholicism as if a light bulb had told him that the situation would improve if he could convert me. He wanted us to pray together but first I had to put something on more appropriate than shorts. So we asked God’s forgiveness for our bestial ways. He used the word ‘bestial,’ then we drove down to the Papago Reservation. Most of the Papagos are quite fat because we changed their diet and over half of them have diabetes. I held a Papago baby which made me want another one but age forty-three is borderline. Perhaps I’m making him sound stupid but he knows a great deal about Indians, South America, and a grab bag that he calls the ‘mystery of the cosmos,’ including astronomy, mythology, anthropology. On the way home we stopped to get out of the car to look at the sunset. He gave me a hug and managed to get excited after being so high-minded. I said No, not if you’re going to make me ask forgiveness for being bestial. So we did it up against a boulder and some Papagos beeped their pickup horn and yelled Padre when they passed. To my surprise he sat down with his bare butt on the rocky desert floor and began laughing so I laughed too.”

A week after I returned to Santa Monica she called to say that her priest was being sent to Costa Rica with all due speed. She hoped she was pregnant but her best chances were the last few days before his departure and he wasn’t cooperating due to a nervous collapse. His movements were also being monitored by an old priest who was a recovering alcoholic. She said the two of them together reminded her of the Mutt and Jeff comic strip. She sounded untypically merry on the phone, enjoying the rare whorish feeling she was sure would pass. One of her blind students had also done particularly well in a piano competition. I told her to call the day he left because I was sure she would need someone to talk to.

All of us work. My mother has an involved theory of work that she claims comes from my father, uncles, grandparents, and on into the past: people have an instinct to be useful and can’t handle the relentless everydayness of life unless they work hard. It is sheer idleness that deadens the soul and causes neuroses. The flavor of what she meant is not as Calvinist as it might sound. Work could be anything that aroused your curiosity: the natural world, music, anthropology, the stars, or even sewing or gardening. When we were little girls we would invent dresses the Queen of Egypt might wear, or have a special garden where we ordered seeds for vegetables or flowers we had never heard of. We grew collard greens which we didn’t like but our horses did. The horses wouldn’t eat the Chinese cabbage called “bok choy” but the cattle loved it. We got some seeds from New Mexico and grew Indian corn that had blue ears. Mother got a book from the university in Lincoln to find out what the Indians did with blue corn and we spent all day making tortillas out of it. It is difficult to eat blue food so we sat there in the Nebraska kitchen just staring at the pale-blue tortillas on the platter. “Some things take getting used to,” Naomi said. Then she told us a story we already knew how her grandfather would fry grasshoppers in bacon grease until they were crispy and eat them while listening to Fritz Kreisler play the violin on the Victrola. She rather liked the grasshoppers, but after he died she never fixed them for herself.

Ruth was better at horses though I was a few years older. Horses were our obsession. Childhood is an often violent Eden and after Ruth was thrown, breaking her wrist when her horse tripped in a gopher hole, she never rode again. She was twelve at the time and missed a piano competition in Omaha that was important to her. This is a small item except to the little girl to whom it happens. We were maddened by her one-hand practice, until Mother bought some one-hand sheet music. Our closest neighbors were three miles away, a childless older couple, so I rode alone after that.

Dear Son! I am being honest but not honest enough. Once up in Minnesota I saw a three-legged bobcat, a not quite whole bobcat with one leg lost to a trap. There is the saw about cutting the horse’s legs off to get him in a box. The year it happened to me the moon was never quite full. Is the story always how we tried to continue our lives as if we had once lived in Eden? Eden is the childhood still in the garden, or at least the part of it we try to keep there. Maybe childhood is a myth of survival for us. I was a child until fifteen, but most others are far more truncated.

Last winter I worked at a clinic for teenagers who “abused” drugs and alcohol. It was a public mixture of poor whites and Latinos from the barrio close by in El Segundo. A little boy—he was thirteen but small for his age—told me he needed to go to the doctor very badly. We were talking in my small windowless office and I made a note of the pain he was in which I misinterpreted as being mental. I speak Spanish but was still getting nowhere on the doctor question. I got up from the desk and sat beside him on the couch. I hugged him and sang a little song children sing in Sonora. He broke down and said he had a crazy uncle who had been fucking him and it had made him sick. This wasn’t shocking in itself as I had dealt with the problem, though it almost always concerned girls and their fathers or relatives. Franco (I’ll call him) began to pale and tremble. I checked his pulse and drew him to his feet. The blood was beginning to soak through the paper towels he had stuffed into the back of his pants. I didn’t want to chance a long wait in emergency at the public hospital so I rushed him to the office of a gynecologist friend. The anal injuries turned out to be too severe to be handled in the office, so the gynecologist, who is a compassionate soul, checked the boy into a private hospital where he immediately underwent surgery for repairs. The doctor and I went for a drink and decided to split the costs on the boy. The doctor is an ex-lover and lectured me on the way that I had jumped over all the rules of the case.

“First you call the county medical examiner. . . .”

“Then I call the police, suspecting a felony. . . .”

“Then you wait for a doctor from Bombay who got his degree in Bologna, Italy. He’s been awake all night sewing up some kids after a gang fight. The doc is probably wired on speed.”

“And the police will need the boy’s middle name, proof of citizenship, photos of his ruptured ass. They’ll want to know if he’s absolutely sure his uncle did this to him.”

And so on. The doctor stood at the sound of a Japanese alarm clock that was his beeper. He went to the phone and I hoped it wasn’t bad news about the boy. He returned and said no, it was just another baby about to be born backward into the world. The couple was rich and he would charge extra to help make up for his misbegotten generosity to the boy. I had another drink, a margarita because it was a hot day. I looked through the sugar gums and the palms across Ocean Avenue to the Pacific. How could all this happen when there was an ocean? For a long time I thought of every boy I saw as possibly my own son, but I never could properly adjust the ages. I am forty-five now so my son would be twenty-nine, an incomprehensible figure for the small, shriveled red creature I only saw for a few minutes. When I was in college the child was always a kindergartner. When I graduated the child was actually nine, but to me he was still five, one of a group tethered together with yarn on a cold morning waiting for the Minneapolis museum to open. When they got tangled I helped a patient schoolteacher straighten out the line and wipe some noses. I worked in a day-care center one day for a few hours but I couldn’t bear it.

Two modest drinks made me simple-minded. I walked out into the bright sunlight, got in my car, and checked for an address in the boy’s file which I brought along for hospital information. I thought I’d reason with the mother in the probability that she was ignorant of the rape. It was the beginning of rush hour on the Santa Monica Freeway, and if you are to leave Santa Monica itself you must become a nickel-ante Buddhist. Usually I established a minimal serenity by playing the radio or tapes, but the music didn’t work that day.

Now there’s a specific banality to rage as a reaction, an unearned sense of cleansing virtue. And what kind of rage led the uncle to abuse the boy? I would do my best to see him locked up but my own rage came from within, from another source, while it was the boy who was sinned against. Only the purest of heart can become murderous for others.

I parked on a crowded street in front of the barrio address. A group of boys were loitering against a stucco fence in front of the small bungalow. They taunted me in Spanish.

“Did you come to fuck me, beautiful gringa?”

“You have some growing to do, you miserable little goat turd.”

“I am already big. Do you want to see?”

“I forgot my glasses. How could you be my lover when you spend your days playing with yourself? Is this the house of Franco? Where is his mother?”

The boys, all in their early teens, were delighted with my unexpected gutter Spanish.

“His mother went away with a pimp. Where is our friend?”

The boys shrank back and I turned to see a man striding toward me with implausibly cruel eyes. The eyes startled me because they belonged to someone long dead whom I had loved. I tried to move away but his eyes slowed me and he grabbed my wrist.

“What do you want, bitch?”

“If the mother isn’t here I want to speak to the uncle of Franco.” Now he was twisting my wrist painfully. “I want to stop this man from fucking his nephew to death.”

Still holding my wrist he vaulted the fence and began slapping me. I turned to the boys and said, “Please.” At first they were frightened but then the one who had teased me pulled out a collapsed car aerial, stretched it to its full length, and whipped it across the uncle’s face. The uncle screamed and let go of my wrist. He turned to attack the boys but they had all taken out their aerials and flailed at the man who ran in circles trying to cover his eyes. The aerials whistled through the air tearing the man’s skin and clothing to shreds. He was a bloody, god-awful mess and now I tried to stop the boys but only a police car careening down the street toward us stopped them. The boys ran, one of them slowing to throw a rock at the squad car which broke the windshield. The uncle disappeared into the house and, evidently, out the back door since the police never found him.

The aftermath was predictably unpleasant. I was suspended, then offered a clerkish job, and refusing that, was fired. The dreadful thing to me was that my impulsiveness allowed the uncle to escape, not the number of infractions of social-work rules I had violated. The police made a cursory attempt at a follow-up the next afternoon at the hospital. I went along as a translator but the boy refused to answer any of the questions, telling me it was a private matter. I was puzzled by this until in the corridor the police told me that such offenses among country people from Mexico are considered unsuitable for the law. It’s something that has to be dealt with individually or by a family member. I said that the boy was far too young to begin to deal with his uncle. The police replied the boy might wait for years until he felt capable.

At dawn a few days later Franco called to say he had sneaked out of the hospital. He insisted that he was fine and would pay me back some day. I was terribly upset because I had visited him the day before and we had had a wonderful time talking, though he still looked very ill. I was frantic and insisted that he call me collect every week, or write me letters. In case he returned to Mexico I told him to contact my old uncle Paul, the geologist and mining engineer, who lived in Mulege on Baja when he wasn’t visiting a girlfriend at Bahia Kino on the mainland. The boy said he didn’t have a pencil and paper but perhaps he would remember. And that was all.

I made coffee and took it out to my small balcony. It was barely light and there was a warm stiff breeze mixed with the odor of salt water, juniper, eucalyptus, oleander, palm. The ocean was rumpled and gray. I think I stayed here this long because of the trees and the ocean. One year when I was having particularly intense problems I sat here for an hour at daylight and an hour at twilight. The landscape helped me to let the problems float out through the top of my head, through my skin, and into the air. I thought at the time of a college professor who told me that Santayana had said that we have religion so as to have another life to run concurrently with the actual world. It seemed my problem was refusing this dualism and trying to make my life my religion.

The wind off the Pacific cooled and the clarity of the air brought on a dim memory, a blurred outline of sensations similar to déjà vu. It was a year or so after World War II, I think. I must have been six or seven and Ruth was three. My father liked to go camping for pleasure and to get away from the farm. The four of us flew up to the Missouri River in the Stinson, landing on a farmer’s grass strip. The farmer was an improbably tall Norwegian and helped Dad load the gear on a horse-drawn wagon. We sat on the gear and bedding with Naomi holding Ruth. There was the smell of ripe wheat, the sweating horses, and tobacco from Dad and the farmer. Under the wagon seat I could see manure on the farmer’s boots, and through a crack on the wagon floor the ground was moving beneath us. After miles of a trail beside the wheat the wagon moved down a steep hill along a creek bordered by cottonwoods; the creek flowed into the Missouri which was broad, slow, and flat. The grass was deep and there were deer, pheasants, and prairie chickens, flushed by our wagon. Mother started a fire and made coffee while Dad and the farmer set up camp. Then they had coffee with sugar and strong, pungent-smelling whiskey. The farmer left with the wagon and horses. Dad put shells in his shotgun and we walked back up the hill and along the edge of the wheat field where he shot a pheasant and a prairie chicken. I got to carry the birds for a while but they were heavy so I rode on his back. At the camp we all plucked the feathers off the birds except baby Ruth who put feathers in her mouth. Dad cut up the birds and they browned them, put in carrots, onions, and potatoes. They put the pot over the fire and we all went down to the creek mouth and went swimming. After dinner the setting sun turned the river orange. At night there was an orange moon and I heard coyotes. At first light I watched my parents sleep. Little Ruth opened her eyes, smiled at me, and went back to sleep. I walked alone down to the river. The wind came up strongly and the water smelled raw and fresh. A large eddy and sandbar were full of water birds. There was a bird taller than myself which I recognized from Naomi’s Audubon cards as a great blue heron. I walked farther up the bank of the river until I heard them calling “Dalva.” I saw Father walking toward me with a smile. I pointed to the heron and he nodded and picked me up. I let my cheek rub against his unshaven face. Soon after that trip we drove him to the train one October afternoon. They told us his plane was shot down outside of Inchon. We did not get a body back, but buried an empty coffin as a gesture.

Ruth called again this morning with good but tentative news. Sex has returned her sense of playfulness. Her voice is no longer dry and fatigued, though I worry a bit that this is a vaguely manic phase that the family is susceptible to. What she did is have the priest in for dinner, along with his “bodyguard” or chaperone, the older priest with the drinking problem. It was a well-planned campaign to win her last chance to get pregnant: she poached Maine lobsters, chilled them, and served them as an appetizer with a Montrachet. Ted is an oenophile and sends her additions to the cellar they began together. Next was some quail she had marinated, then grilled, and finally a rough-cut filet covered with garlic and pepper, with a Grands Echezeaux and her last bottle of Romanée-Conti. The old priest was a delightful talker and had studied in France in the thirties. He had always been poor and had never drunk such wines, though he had read of them, and he’d be damned if at age seventy-one he’d miss the chance to drink them. I teased Ruth then about her somber and pious comments on prostitutes when she had served over a thousand dollars’ worth of wine in order to make love. She said the old man never did fall asleep, so she had to settle for a quick act standing in the bathroom over the sink looking at each other in the mirror. Now all she had to do was wait and see if she was pregnant while the father went off to work among the poor in Costa Rica.

Here is how it happened to me, how I had my child early in my sixteenth year. It has often occurred to me that I may be a grandmother at forty-five. I tried it out in front of the mirror, whispering grandma at myself softly but it was all too unknowable to be effective. But now I am drifting away from it again. Naomi and Ruth feel wordlessly upset that the land will go to Ruth’s son, there being no other heirs in the prospect, another reason for the priest mating. None of us mind the name Northridge disappearing, but it would be a shame to see the land leave the family, and Ruth’s son professes to hate it and has not visited since his early teens. Enough!

His name was Duane, though he was half Sioux and he gave me many versions of his Sioux name depending on how he felt that day. Grandfather’s place, which is the original homestead, is three miles north of the farm. The homestead was a full section, six hundred and forty acres, onto which the other land had been added since 1876, to form a total of some thirty-five hundred acres, which is not that much higher than average for this part of the country. Our good fortune was that the land is bisected by two creeks that form a small river, so that the land was low and particularly fertile, and could easily be irrigated. The central grace note, though, is that my great-grandfather studied botany and agriculture for two years at Cornell College before he entered the Civil War. In fact, an accidental traveler down the county gravel road near Grandfather’s would think he was passing a forest, but this is a little far-fetched since the farm is so far from the state highway that there are no accidental travelers. All the trees were planted by Great-grandfather to form shelter belts and windbreaks from the violent weather of the plains, and to provide fuel and lumber in an area where it was scarce and expensive. There are irregular rows of bull pine and ponderosa, and the density of the deciduous caragana, buffalo berry, Russian olive, wild cherry, juneberry, wild plum, thornapple, and willow. The final inside rows are the larger green ash, white elm, silver maple, black walnut, European larch, hackberry, wild black cherry. About a decade ago Naomi, through the state conservationists, made the area a designated bird sanctuary in order to keep out hunters. Scarcely anyone visits except for a few ornithologists from universities in the spring and fall. Inside the borders of trees are fields, and ponds, a creek, and inside the most central forty, the original farmhouse. Enough!

Duane arrived one hot late August afternoon in 1956. I found him walking up the long driveway, his feet shuffling in the soft dust. I rode up behind him and he never turned around. I said, May I help you? but he only said his own and Grandfather’s names. He was about my age I thought, fourteen, scarred and windburned in soiled old clothes, carrying his belongings in a knotted burlap potato sack. I could smell him above the lathered horse, and told him he better jump on my horse because Grandpa had a pack of Airedales who wouldn’t take warmly to a stranger. He only shook his head no, so I rode ahead at a gallop to get Grandpa. He was sitting on his porch as usual and at first was puzzled, then intensely excited though noncommittal. He had to wait at the pickup as I patted each of the half-dozen Airedales on the head before they jumped in the back of the truck. If I didn’t pat each one in turn they would become nasty to each other. I loved these uniquely cranky dogs partly for the way they welcomed me, and how wildly excited they became when I went riding and invited them along. I never took them when I rode into coyote country because the dogs once dug up and ate a litter of coyote pups despite my efforts to fight them off with my riding crop. After they gobbled up the pups the dogs pretended to be ashamed and embarrassed. Enough!

We found Duane sitting cross-legged in the dust. The dogs set up a fearsome howl but never dared jump out of the truck without Grandpa’s permission. We got out and Grandpa knelt beside Duane who wasn’t moving. They spoke in Sioux and Grandpa helped Duane to his feet and embraced him tightly. When we got back to the house Grandpa said I should leave, and to tell no one at our place of the visitor. Despite the passage of seven years or so he still partly blamed Naomi for letting Father go back to war, and they were frequently at odds.

I’m sure I loved Duane, at least at the beginning, because he so pointedly ignored me. He came from up near Parmelee on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, and though his looks were predominantly Sioux his eyes were Caucasian, cold and green like green stones in cold flowing water. Technically he was a cowboy—it was all he knew how to do and he did it well. He refused to live in Grandpa’s house but took up residence in a shed that was once a bunkhouse. Two of the Airedales decided to live with him of their own accord. Duane refused to go to school; he told Grandpa that he could read and write and that was as far as he needed to go in that area. He spent his time looking after the remaining Herefords, repairing farm buildings, cutting wood, with the largest chore being the irrigating. The only other hired hand was Lundquist, an old Swede bachelor friend of Grandpa’s. He taught Duane irrigating and jabbered all day on the matter of his own Swedenborgian version of Christianity. Lundquist daily forgave Duane for the death of a distant relative in Minnesota who was murdered during the Sioux uprising in the mid-nineteenth century. The actual farmwork wasn’t that onerous since Grandpa mostly grew two crops of alfalfa a year within his forest borders, and the bulk of the rest of our land was leased on shares to neighbors.

On New Year’s Day of that first year Duane received a fine buckskin quarter horse from a cutting-horse strain, plus a handmade saddle from Agua Prieta on the Arizona border. Normally the gift would have come on Christmas but Grandfather had lost his religion during World War I in Europe and didn’t observe Christmas. The day stands out clearly: it was a warmish, clear winter morning with the thawing mud in the barnyard a little slippery. I had gone way over to Chadron with Grandpa the day before to fetch the horse, and the saddle had come by mail. Duane came riding in on the Appaloosa from feeding the cattle and saw me standing there holding the reins of the buckskin. He nodded at me as coolly as usual, then walked over and studied the horse. He looked at Grandpa who stood back in the sunlight against the barn. “Guess that’s the best-looking animal I ever saw,” Duane said. Grandpa nodded at me, so I said, “It’s for you, Duane.” He turned his back to us for a full ten minutes, or what seemed an unimaginably long time given the situation. Finally I came up behind him and ran my hand with the reins along his arm to his hand. I whispered “I love you” against his neck for no reason. I didn’t know I was going to say it.

That was the first day Duane let me go riding with him. We rode until twilight with the two dogs until I heard Naomi ring the dinner bell in the distance. Duane rode across the wheat stubble until he turned around within a hundred yards of our farmhouse. It was the most romantic day of my life and we never spoke or touched except when I handed him the reins.

One of the main sadnesses of my life at that time, and on occasions since, is that I matured early and was thought by others to be overly attractive. It isn’t the usual thing to be complained about but it unfairly, I thought, set me aside, brought notice when none was desired. It made me shy, and I tended to withdraw at the first mention of what I looked like. It wasn’t so bad in country school where Naomi was the sole teacher and there were only four of us in the seventh grade, but for eighth grade I had to take the school bus to the nearest town of any size which, for certain reasons, will be unnamed. There the attention was constant from the older town boys and I was at a loss what to do. I was thirteen and refused all dates, saying my mother wouldn’t let me go out. I also refused the invitation to become a cheerleader because I wanted to take the school bus home to be with my horses. I trusted one senior boy because he was the son of our doctor and seemed quite pleasant. He gave me a ride home in his convertible one late-April day, full of himself because he had been accepted by far-off Dartmouth. He tried very hard to rape me but I was quite strong from taking care of horses and actually broke one of his fingers, though not before he forced my face close to his penis which erupted all over me. I was so shocked I laughed. He held his broken finger and began crying for forgiveness. It was stupid and profoundly unpleasant. Naturally he spread it around school that I had given him a great blow-job, but school was almost out for the year, and I hoped people would forget.

If anything ninth grade was worse. Mother insisted I dress well, but I hid some sloppy clothes to wear in my school locker. I played basketball for a month or so but quit after another unpleasant incident. The coach kept me very late, well after everyone had left, to practice free throws, and to play one on one. While I was drying off after a shower he simply walked right into the girls’ locker room. He said he wouldn’t hurt me or even touch me but he wanted to see me naked. I was quite frightened when he came closer saying Please over and over again. I didn’t know what to do so I dropped the towel and turned all the way around. He said Once more so I did it again and then he left. When I got in the car I almost told Naomi but I knew that the coach had three children and I didn’t want to make trouble for him.

In contrast to other males Duane hadn’t shown a trace of affection in the year and a half since his arrival. All that we shared was the love of horses but that drew us together sufficiently to give me enough solace to keep going. At one point I had become so depressed I thought of maiming myself, burning my face, or ending my life. Naomi wanted to take me to a psychiatrist in the state capital but I refused. One evening she gave me my first glass of wine and sent Ruth out of the room. I told her much of what was bothering me and she held me and wept with me. She said that what was happening to me was the condition of life, and that I had to behave with pride and honor so that I could respect myself. When I found someone to love who loved me it would all make more sense and become much better. I didn’t tell her I loved Duane because she thought him so rude as to be mentally diseased.

One Saturday I was hazing some young steers for Duane so he could practice his buckskin on cutting, which is when the rider allows the horse to enter the herd, select a steer, and “cut” him out of the herd. My job was to keep the steers from dispersing and running off in every direction. The oldest Airedale understood the game and helped me to turn back especially recalcitrant steers. I think the dog stuck it out merely for the outside chance of getting to bite a steer.

That day it began to sleet so we went in the barn and practiced roping on some old steer horns perched on a pole. We practiced team roping together when the weather was good. I was the “header,” that is, I lassoed the horns while Duane was the “heeler,” which was much harder because you have to lasso the back hoofs of a running steer. Duane seemed especially cold and removed that day so I tried to tease him about a necklace he wore. He wouldn’t tell me what the necklace meant no matter how I badgered him.

“I heard two footballers down at the feed store say you were the best-looking girl in school,” he said, knowing how much it bothered me. “They also said you were the best fuck in the county.”

“That’s not true, Duane.” I had broken into tears. “You know that’s not true.”

“Why would they say it if it wasn’t true?” he asked, grabbing my arm and making me face him. “You never offered it to me because I’m an Indian.”

“I would do it with you because I love you, Duane.”

“I’d never fuck a white girl anyway. Not one who’d fuck those farmers.”

“I’m a little bit Indian and I didn’t fuck those farmers.”

“There’s no way you can prove it,” he yelled.

“Make love to me and then you can tell I’m a virgin.” I began to take off my clothes. “Come ahead you big-mouth coward.” He only glanced at me; then his face became knotty with rage. He ran out of the barn and I could hear the pickup starting.

When I rode home I couldn’t stop crying. I wanted to die but couldn’t decide how to go about it. I stopped along a big hole in the creek, now covered with ice, that we used for swimming in the summer. I thought of drowning myself but I didn’t want to upset Naomi and Ruth. Also I was suddenly very tired, cold, and hungry. It was still sleeting and I hoped the ice would break the power line so we could light the oil lamps. After dinner we’d play cards on the dining-room table beneath portraits of Great-grandfather, Grandfather, and Father. I would think, Why did he leave us alone to go to Korea?

After dinner Grandpa pulled into the yard in his old sedan, which startled us because he always drove the pickup. Naomi and I had to go into town with him because Duane was in jail and they needed my part of the story. In the sheriff’s office I said I had never had anything to do with the bruised and severely battered football players. Grandfather was enraged and the sheriff cowered before him. The parents of the football players were frightened, perhaps unfairly, because Grandfather is rich and we are the oldest family in the county. When they brought Duane out of the cell he was unmarked. The football players tried to sneer, but Duane looked through them as if they weren’t there. The sheriff said that if anyone slandered me again there would be trouble. Grandpa said, “One more word and I’ll turn all of you filth straight back to Omaha.” The parents begged forgiveness but he ignored them. I could see he was enjoying his righteous indignation. Out in the parking lot of the county building I said thank you to Duane. He squeezed my arm and said, “It’s fine, partner.” I almost fell apart when he called me “partner.”

I was not bothered by the boys at school after that, though I was lonely and I was given the behind-the-back nickname of “Squaw.” I didn’t mind the nickname; in fact, I was proud of it, because it meant in the minds of others that I belonged to Duane. When he found out, however, he laughed and said I could never be a squaw because there was so little Indian in me as to be unnoticeable. This made me quarrelsome and I said, Where did you get those hazel-green eyes if you’re so pure? His anger seemed to make him want to tell me something, but he only said he was over half Sioux and in the eyes of the law that made him Sioux.

After that we didn’t have anything to do with each other for a month. One summer evening when Grandpa was over for dinner he took me aside and told me it was a terrible mistake to fall in love with an Indian boy. I was embarrassed but had the presence to ask him why his own father had married a Sioux girl. “Who knows why anybody marries anybody.” His own wife, whom I never saw and who was long dead, had been a rich girl from Omaha who drank herself into an early grave. “What I’m saying is they aren’t like us, and if you don’t behave and stop chasing Duane I’ll send him away.” It was the first time I stood up to him. “Does that mean you’re not like us?” He hugged me and said, “You know and I know I’m not like anybody. You show the same signs.”