0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

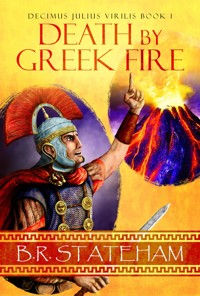

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

After twenty years as a professional soldier, Decimus Julius Virilis - distant kin to the Imperator himself - has been commissioned the third in command of the newly formed Legio XII Brundisium.

It's his last assignment before retiring from Caesar Augustus’ legions - and turns out to be much more dangerous than he anticipated. After being shipped off to Dalmatia to fight the rebels waging war against Rome, the untrained legion immediately blunders into a death trap deep in enemy territory, leaving the commanding officer and his lieutenants dead.

Decimus is commanded by the heir apparent, Tiberius Caesar, to find the mastermind who planned the diabolical trap and is attempting to plunge the Roman Empire back into a civil war. But can the Roman tribune see the unseen and solve a crime others think is impossible?

Set in the time of the Roman Empire, Death By Greek Fire is the first book in B.R. Stateham's 'Decimus Julius Virilis' series of historical mystery novels.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

DEATH BY GREEK FIRE

DECIMUS JULIUS VIRILIS

BOOK ONE

B. R. STATEHAM

CONTENTS

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2022 B.R. Stateham

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Charity Rabbiosi

Cover art by Lordan June Pinote

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

I

7 AD

Dalmatia

On a hilltop overlooking a mountain valley road

Death comes in the deepest portion of the night. Suddenly and without warning. Especially here. Deep in enemy territory surrounded by sullen mountains shrouded in dark forests underneath low-lying carpets of icy fog. Unseen death stalks the careless. An arrow from out of the darkness. The sudden thud of a hurled javelin cracking into one's lorica segmentata. The unexpected surge of a black figure rising out of the darkness followed by the swift stroke of cold steel across yielding flesh. In the night death comes sudden, swift and sure.

Especially here, on this strangely quiet, foreboding night in Dalmatia. The promise of death so near in the darkness, it was making the entire legion nervous and fidgety. He knew from his long experience soldiering what fear could do to a legion. A legion spooked and restless on the night before a possible battle contained all the ingredients for disaster. Fear could make a legion, led ineptly, to bend. To yield ground. And eventually to shatter like cheap pottery thrown onto a cold stone floor.

Not that the commander was inept. Inept was a harsh descriptor. Inept connoted incompetence and a casual disregard of assigned duties. Young would be a better description. Inexperienced. Thrust into the command of a legion long before he was ready for it. The young Gaius Cornelius Sulla was just old enough to be elected into the Roman Senate. Old enough, but contrary to tradition and Roman law, the young Senator had never served in the army. Never held one of the minor political offices which were normally prerequisites before running for a Senator's seat. Money, and his father's reputation, allowed the boy to bypass mere formalities. He was suitably impressed with the duties of being a legion commander. He wanted to prove to his father he was the man and son his father wanted. It was just that … well … the lad was but a boy. A boy given the command of a Roman legion which was sorely below nominal strength in manpower and finding itself hurled into the depth of enemy territory without proper training and equipment.

Youth untrained, and a legion improperly handled, were the ugly ingredients needed for a recipe of unparalleled disaster.

Twenty plus years serving in one legion or another had painted for him, on several occasions, what the end results of a legion shattering like a piece of thin glass would be. A horror beyond description. The killing would be endless. Roman soldiers throwing down their shields and swords as they ran from the battlefield in a mass panic only to be ridden down by the enemy's cavalry or assaulted by roving bands of sword and axmen. Hacked to pieces or ran through by fast riding cavalry, the memories of his past burned brightly in his mind. He knew if such a debacle happened on the morrow there would be few, if any, survivors. Especially here in this mountainous country overran with ravaging madmen filled with bloodlust and hate for anything Roman. That's why, throwing a heavy campaign cloak over his shoulders as he stood near the warmth of a burning brazier, he preferred inspecting the army's perimeter in person.

Stepping out of his tent, pulling the heavy wool cloak tighter around his shoulders, he took his time setting his bronze helm over his brow before reaching for his officer's baton firmly clamped under his right armpit. On either side of his tent's entrance, the two legionnaires snapped to attention and saluted in perfect unison. Acknowledging their salutes with a wave of his baton, he eyed the camp to his right and left in silence, then turned his attention to the nine legionnaires standing directly in front of him.

The young decanus, or a contriburnium commander of eight men, saluted smartly as the eight legionnaires behind him snapped to attention. One glance from his old eyes told him he and his men had spent some time getting their armor cleaned and smartly arrayed. The decanus was, at best, eighteen or nineteen years old. He, like his men, were not much more than raw recruits swept up off the streets of Brundisium and Rome and sent packing off to Dalmatia. Dalmatian tribesmen were in revolt. Again. And Roman authority, again, being challenged. The decanus was so young his beard was nonexistent. So frail of bone he wondered how in Hades the lad stood upright in the thirty or more pounds of standard legionnaire armor assigned to each man. Nevertheless, the lad was standing tall and proud. His men looked smartly attired and diligent. It didn't matter if the contriburnium was of the 7th cohort. The 7th being the cohort of the youngest, most untrained soldiers.

Lads beginning their long, arduous, and sometimes quite deadly learning phase of becoming a professional soldier. In the young eyes of these nine men, he could see they were looking for some sign of hope. Some gesture that they might survive in what was, obviously, a desperate situation. And without a doubt it was a desperate situation. Surrounded on three sides by determined foes who vastly outnumbered them. Intent on throwing off the yoke of Roman rule, the six or so main Dalmatian tribes united and waged war on anything which hinted of imperial power. This newly formed legion, Legio IX Brundisi, was within their grasp. A new legion, vastly undermanned, yet swept up into the fight because of the threat of a foe so close to the shores of Rome itself.

It was a hodgepodge collection of veterans and raw recruits. And he, Decimus Julius Virilis, being third in command, was the legion's Praefectus Castoreum. His main duty, of the many assigned to him, was to throw this collection of madmen together and hone it into a fighting machine as quickly as possible. A vastly important job given only to a professional soldier who had come up through the ranks and had proven himself to be both tough and enduring, as well as loyal and intelligent. A job that never ended. He had ordered a contriburnium from the 7th to be his personal escort tonight as he inspected the legion's perimeter. Yes, a move fraught with danger, perhaps. Especially so if the rebels decided to assault the legion's defensive lines hidden behind the veil of darkness.

In all the world there was no fighting force as well trained, well organized, and more victorious, than that of the seasoned professional legions of Rome. For almost four hundred years Roman legions fought the armies of just about every foe in what would become, eventually, modern Europe. Greeks, Etruscans, Carthaginian, Egyptian, Spaniards, Parthians, Germans, Gauls. The list was endless. For four hundred years Rome’s steel had, by in large, remained victorious. Yet four hundred years of military dominance guaranteed one certainty. There would be no peace, no tranquility in an empire forged from steel and strife. There would always be someone, somewhere, ready to rise up and defy the Roman yoke.

Eyeing the darkness and low hanging clouds of fog surrounding the hilltop the legion now commanded, Decimus could feel the weight of the coming battle resting on his tired shoulders. It would be a desperate fight. An unwanted fight. The legion was seriously undermanned. It was alone, deep in enemy territory, miles away from the main Roman army under the command of Tiberius Caesar.

Caesar, the adopted son of Caesar Augustus, had been summoned by his father to return to Rome and take command of the ten or so legions being assembled to fight the Dalmatian rebellion. The general had been in the north, beyond the Alps, fighting Gaul and Germanic tribes and trying to stabilize the northern borders. But the Dalmatian uprising, so dangerously close to the Latin homelands, took priority. The rebelling tribes were directly east of Rome—just across the watery finger of the narrow Adriatic Sea. A failure of her legions now would directly threaten Rome itself. Therefore, her best general was summoned to take command of the legions assembled to put the rebellion down.

Legio IXth Brundisi had been hastily recruited, marginally equipped, and shipped off to Dalmatia before being properly trained. The legion was almost two thousand men short of a legion’s nominal six thousand men strength. Without its cavalry contingent of four hundred or more horsemen, with each of the legion’s eight cohorts drastically undermanned, their disastrous arrival in the Illyricum port of Asa was like a prophet’s decree of looming defeat to come.

A mysterious fire erupted among the ships in the harbor and spread its ravenous hunger across the small fleet which escorted the legion’s troopships to Asa. Dalmatian spies infiltrated the Roman-held port and somehow set fire to all of the legion’s troopships only moments after the last man of the legion had disembarked. The hungry flames spread from ship to ship, lighting up the harbor’s night with a terrifying display of light and smoke, and continued to ravenously devour ships far into the next three days.

Bad luck continued to haunt the IXth Brundisi as they left Asa and marched into the depths of the rebel held territory. Leaving the port, rebels began to attack the rear and flanks of the columns of the marching legion with sudden, deadly attacks by small units of bowmen who hit hard, and just as swiftly faded back into the forests before any counterattack could be organized. The continuous loss of one or two men with each swift attack was telling. Untrained recruits not used to the hardships of war sulked and stewed in their thoughts when the legion finally made camp at night.

He saw it in the men’s eyes. The lack of sleep. The lack of trust in the legion’s legate. All of it was combining to create that deep-set feeling of fear which, if allowed to grip the hearts of all, was unquestionably a recipe for a disaster waiting to happen. It rested on his shoulders as the legion’s Praefectous Castorum, the legion’s most experienced veteran, to train these men into a fighting unit.

Nodding to the young decanus, Decimus set off with a firm step to inspect the legion’s perimeter, not knowing that within moments, an unimaginable disaster was soon to turn the dark Dalmatian night into the raging fires and billowing roar of a Grecian Hades nightmare.

II

7 AD

Dalmatia

The Fires of Hades

Whatever it was which made him pause and turn his head to look, he would never be able to say. But he did. And it possibly saved his life. He came to a halt on a slight rise of dirt, surrounded by his escorts, his mind intent on keeping his men ever alert. The night was a thick envelope of dark and oddly silent to the ear. Not even a breath of cool mountain air stirred in the thick blackness. In the darkness, just below the hill, the ground opened into a wide space of flat valley floor. Meandering down the middle of the valley was a road which ran from Asa on the coastline deep into the Dalmatian interior. On both sides of the valley were high, forest covered mountains. Rugged forested mountains pockmarked with the burning pinpricks of hundreds of campfires of the enemy.

Clearly visible. A constellation of man-made fireflies flickering brightly in the cloying darkness of the moonless night. Dalmatian rebels who, each one, had in their chests a burning hatred for anything Roman.

To his right—the outer defenses of the legion’s camp, rows upon rows of wooden stakes driven into the soft dirt of the small hill. Beyond the stakes, a deep ditch with sloping sides encased the camp. Work was completed by every last member of the legion in a matter of a few hours. Like all Roman camps, this one was an almost perfect square precisely mapped out and plotted by the legion’s attached engineers hours before the first of the legion’s cohorts came marching up the road. All legionnaire camps were the same. It didn’t matter if you soldiered in Mauritania in far off Africa or slogged away in a unit a thousand leagues away in the cold and ice of distant Celtic Britain. A Roman army camp was the same. A legion would march for a little over half of the daylight hours in a precisely ordered marching formation, a concisely ordered marching order all legions of the army adhered to since the days of the legendary Scipio Africanus, the Roman general who defeated Hannibal and ultimately destroyed Carthage almost four hundred years earlier.

But, usually four hours before sunset, the legion would come out of its marching formation and build a fortified camp atop some piece of elevated terrain which gave the legion an unhindered 360 degree of visibility of its immediate environs. It was the Roman way. It was inviolate Roman tradition. It was one of the many little pieces of the puzzle which made the Roman Army invincible.

Each marching soldier not only carried his weapons with him, but a wooden stake, or a shovel, or a pick, as well. Each man pitched in to build the camp. It took about four hours to complete. But by the time it was done, every soldier in the camp knew exactly where his cohort resided and where his tent would be found. And it was Decimus’ job to make sure the legion performed to exact standards without exception.

But on this night, he paused atop a small mound of freshly discarded dirt and turned to his left to look up the hill toward the legate’s tent. The darkness in the direction toward the legate’s tent was not quite as dense thanks to the burning torches and campfires which littered the camp’s interior. It was not a high hill the legion resided on. Its slopes were relatively gentle to traverse. Decimus noticed the large tent on the summit of the hill, surrounded by soldiers from the general’s personal praetorian guards. Rising above the general’s tent was the masthead which, atop it, displayed the legion’s cherished eagle, along with the many pennants of the legion itself and its eight cohorts underneath. In the semi-darkness of the camp’s burning campfires, he saw the main flap of the general’s tent open and a group of men exit the tent’s interior in mass. In the twilight it looked like five army officers surrounding a large figure wearing a dark cape which covered his entire frame. Light reflected off the polished armor of the Romans as they gathered around the dark figure for a moment or two before disappearing behind the legate’s large tent.

Decimus frowned. From this distance, and with so little light illuminating the night, it was hard to see the faces of the Roman officers. But he was sure he had never seen any of the men before. As for the heavy looking man in his black hooded cloak, his face was never revealed. But he moved like a soldier. A hand lifted up to pull the hood of his cape around his face as he turned to walk away. An act of deception, the Prefect thought to himself. An act of intrigue. But there was a confidence, almost an arrogance, in the way he straightened himself up and moved out of view surrounded by the five Roman officers.

An unexpected chill ran down the Prefect’s spine. Half turning, his brown eyes fell onto the balding, white-haired little man who was his servant, a sour faced old man who had served for years with him in one legion or another. He leaned closer to the older man to speak quietly into his ear.

“Find out who those men were and when they arrived in camp.”

The small man with the balding head and darkly tanned face nodded in silence and turned to leave. He moved through the small entourage of armor-clad legionnaires who surrounded the Prefect, and then started up the incline of the hill toward the legate’s tent.

He took no more than ten steps before the explosion ripped through the night. A roaring crescendo shook the ground violently underneath his sandaled feet and lit up the night with the hellish light of a nightmare. A blast of hot, foul-smelling air threw Decimus, and everyone else standing at their posts, through the air as if he was nothing more than a child’s rag doll. The roar of the explosion droned on and on even as large chunks of soil and rock began raining out of the semi-lit skies. Gigantic chunks of soil and rock hit the ground with a thudding jolt, guaranteeing death and severe pain if some hapless legionnaire stood or laid splayed out underneath the raining fury.

The hot, multi-colored flames shooting up from the top of the hill roared and exploded like the hissing fury of a metal smith’s forge. A forge only conceivable by the gods themselves. Decimus, stunned and in pain, lifted himself up from the ground and staggered to one side as he faced the billowing inferno above him and stared at it in awe. As he watched he saw the flames weakening, the roar of its fury lessening perceptibly, and then, with the blinking of an eye, suddenly ceasing altogether. One moment Hades’ fires burned and screamed in its fury. The next, gone altogether, the night’s darkness suddenly enveloping one and all, the sudden silence slapping everyone across the cheek with a startling clarity almost as overwhelming as the explosion itself.

Reality flooded into Decimus’ mind as he turned and began bellowing out names with the hammer-like staccato force that only someone with twenty years of soldiering could possibly do.

“Menelaus! Romulus! Crassus! Brutus! All tribunes and centurions… to me! To me! The rest of you bastards, off your asses. NOW! Up! Up! Get on your feet, or by the sweet graces of all that is holy, I’ll personally peel the hides off each and every one of you with a cat o’nine tails in the morning!”

Decimus roared. He strode from one point to the next on the outer perimeter cajoling, barking, kicking men up and off their ground and throwing them physically back to their assigned positions. He organized small gathering of legionnaires to fight and subdue the innumerable fires which sprung up in the camp. As he roared and terrified one and all, burly men dressed in the armor of tribunes or centurions staggered or ran to join him. In the eyes of each, Decimus saw disbelief and terror filling their souls. But he knew. Knew this was no time for either emotion.

A catastrophe of Olympian proportions struck the IXth Brundisi. But an even larger, deadlier, catastrophe was about to happen when dawn arrived if the legion was not prepared for it.

“Gnaeus!” the Prefect yelled over the shouting of his centurions taking over at last and rousing the men out of their stunned silence. “Survey the camp. Assess the damages and loss of men and report back to me as soon as possible.”

Decimus turned and stared up at where once the top of the hill had been. Where the legate’s massive tent, the holy shrines of the legion’s namesakes, where the several tents of the officers would be found, all gone. Not just destroyed. But gone! Nothing remained. Not a shred of cloth, or a piece of armor, or even a body part of one of the dead remained. Now there was only a gaping hole twenty meters deep and ten meters in diameter, with an eye-watering aroma of bad eggs drifting up and out of the cavity and blowing gently away with the wind.

It did not take a genius to realize the harsh truth. All of the legion’s officers, except for him, and most of what had been the First Cohort—the legion’s most experienced troops—no longer existed. The anger of an unknown god came down from Olympus and had destroyed one and all. And in the process, possibly assuring the complete and total destruction of everyone who, at the moment, still lived on this cursed hill. Dawn was but only two hours away, and with the first light of a new day, the hills above their position infested with Rome’s enemies would look down upon the middle of the valley and see what had been wrought in the middle of the night.

The enemy would come howling and screaming at them with blood lust in their eyes and the smell of victory upon them. Thousands of them. All sensing a great victory at hand if they but struck with overwhelming force before the sun lifted much higher than dawn’s light in the morning sky. If the Ninthwas not prepared, if not their position was compressed and strengthened somehow, if the men were not ready to fight, all would be lost. By noon every living soul on this hill would be dead. Consigned to the eight levels of Hades for the rest of eternity. A situation Decimus was grimly aware of but determined to contest the issue to his last breath.

The thin, hardened old veteran of a dozen battles, turned to face the many faces of his junior officers staring up at him, hungrily waiting for orders. He began talking in a commanding, but calm voice.

“I want the Second Cohort, Brutus, to take up position on the northern flank of the hill. Pull back from your original position and deploy halfway up the hillside and dig in. Crassus, take the Fourth and deploy directly behind the First. Draco, your Sixth will take the eastern slope. The Seventh will deploy directly behind you. The west slope …”

A calm voice. An assured, experienced commander. And a plan. A plan delivered concisely, with little fanfare, and direct. Decimus’ brown eyes did not waver as he looked into the faces of each of his centurions. Orders were given from an old soldier who had seen it all. The Prefect in his quiet calm, simply radiated self-confidence out to his men like some mystical lantern held up in the dead of night to light the way. No one knew if the Prefect’s plan would work. In some respects, most of the centurions didn’t care. There was a plan. There were orders given and expected to be carried out to the letter. Someone was in charge. Someone they knew and respected.

What more could a soldier ask for or expect?

Only the gods knew what would happen once dawn filled the sky with light.

What remained of the night was filled with the movements of legionnaires repositioning themselves on the hill first, followed by the sounds of men digging into the soil, and hammers thumping loudly onto stout wooden stakes as they tore down the ones set earlier in the day and repositioned them in their new defensive stance.

Decimus, with the silent Gnaeus beside him, kept moving around the hill directing men here and there. Even pitching in when a set of extra hands were needed to drive stakes into the ground or to throw up additional barricades of dirt in front of their positions. No one complained. No one slacked off. Not with the Prefect beside them in the dirt and grime working as hard as they were.

When the first gray shades of predawn began to lessen the darkness around them, everyone knew. They were ready. Ready for whatever might come.

III

7 A.D.

Dalmatia

The Dawn

Fog.

Long wispy lines of white fog clung close to the ground and hugged the high hills with a passionate embrace. Thick, yet alive, for it moved slowly, almost rhythmically, with the gentle breeze blowing from out of the West. Completely hiding everything behind its cool, icy curtain. A brooding entity all its own that held no love for the Ninth. Yet, in its own right, a visual treat he knew he would never forget.

He smiled grimly, gripping his gladius in one hand, and his curved, rectangular scutum, his shield, in the other. He would remember this day, this fog, until his dying day. He smiled, hoping that day would come many, many years away yet.

The one other note of interest about fog, however, he remembered again. It may hide what it covered, or what was behind it. But it enhanced sound manifold. Distorted it. Magnified it. In the process, distorting and magnifying the terrors in the mind of each and every soldier hugging this hill so desperately. He saw several of his younger soldiers visibly shaking in fear as they knelt on one knee behind their scutum and waited for what was to come.

He stepped among the young recruits and spoke to them all. Spoke to each with a word or two. Calm. Assured. As if he was talking to equals around the dying embers of a campfire. He knew his presence as an old and experienced legionnaire and commander of men, was sometimes all that was needed to assuage the fears from men’s hearts. He remembered battles past when he was but a young legionnaire. He felt their fears. Their dread for what was to come. A calm voice, a sudden smile, a quiet word was like an elixir in the ears of the fearful.

Deep in the gray-white mist they heard the approach of their enemy. The clatter of shields and spears clacking against each other. The rumble of men shouting in Greek and Dalmatian, shouting to each other and further fueling their murderous fury. Horses snorting impatiently and nervously. And the blaring notes of horns. Dozens of them. Blaring out three and four note commands only the enemy understood.

And Decimus Julius Virilis as well. The old, scarred veteran.

He had fought the Greeks and Dalmatians before. Watched them gather in their assembled masses. Listened to the wings of their fabled spearmen in their bronze helmed phalanxes communicate to each other via the blasts of their many horns. He knew what was coming. And reacted accordingly.

“Cohorts! Shields up! Ready pilum!”

Like a bolt of lightning cracking across the sky his order shot out across the perimeter of the hill in an instant. Forty-eight centurions, the surviving junior commanders left standing after the devastating explosion, relayed Decimus’ command across the hill with ruthless efficiency. Each centurion commanded eighty men. In a fully manned, fully equipped legion, each cohort’s complement would be six centuries strong. Roughly four hundred eighty men per cohort. But not on this day. The IXth Brundisi landed on the shores of Dalmatia woefully undermanned. And now, with the First Cohort’s demise, Decimus knew he barely had a little over three thousand men alive enough to face an enemy vastly superior in numbers.

Decimus, half turning to face the enemy, watched the swirling pattern of white mist dance before his eyes. Dance and slowly evaporate ever so minutely. But enough to see the first dim outline of the approaching foe.

“Pilum… now!”

The Roman pilum. A short throwing spear, more like a weighted javelin, designed to bury deep into the shield of an approaching enemy. Half of the javelin’s length was the heavy iron head of the spear itself. Heavy, but made of soft iron. The iron soft in order to make it twist and bend out of shape in the shield. The wooden shaft was purposely designed to break off, leaving just the iron head buried stubbornly into an enemy’s shield, thus making the shield too heavy and cumbersome to handle in battle.

One hurled pilum would not make much difference. But four hundred such weapons, hurled at the same time, created a deadly cloud of swiftly falling carnage to the front lines of the oncoming foe. Each legionnaire was armed with two such weapons. Curtains of falling death rained down through the fog on the unsuspecting enemy. Caught unprepared, not exactly sure where the Roman lines were in the fog, the sudden carnage of hurling death caught the Dalmatians by surprise. The explosion of surprise, rage, and pain from the collective mass of falling death onto invisible foes shattered the semi-quiet of the early morning with a cacophony of murder.

The enemy, being distantly related to the Greeks to the south, fought like the Greeks of old. With shield and spears lined up in large blocks, or phalanxes, of infantry which marched slowly and methodically toward the enemy like some gigantic, weighted mass of steel, blood, and sinew. A Greek phalanx was like the mailed fist of Zeus himself, encased in steel and bronze and weighing collectively a thousand tons, smashing into the frailty of yielding human flesh. It wreaked havoc and carnage whenever the blow fell.

For centuries, the Greek style of warfare was the queen of the battlefield. Only heavy phalanx meeting heavy phalanx could defeat this mode of destruction. Until, that is, the Greeks ran up against, centuries earlier, the fledgling martial fervor of Roman arms. Almost two hundred years earlier a Greek general by the name of Pyrrhus of Epirus, at the behest of a minor Greek colony residing on the Italian peninsula, invaded Italia and fought the Romans in a series of battles.

Pyrrhic victories. Costly victories in both manpower and material. So costly that, even though victorious, Pyrrhus’ ultimate goal of building a new kingdom for himself on Italian soil quickly became nothing but a fading dream. Having won battles, nevertheless he lost the war. Because of those costly victories, Pyrrhus and his Greeks were forced to returned to the Greek mainland, where they eventually faded into the pages of history. And Rome began its unstoppable march toward greatness thanks to its martial fervor and unique style of warfare.

While others mimicked the style of the Greeks in making war, Rome fought differently. Rome fought with shield and swords. The scutum and gladius. But more than that, Rome believed in flexibility and organization. Forever adapting, forever modifying its method of organized murder, Rome was unparalleled in the ancient world in its adaptability. All one had to do was look at its weaponry. The fabled short sword, the gladius, came from Spain. As did the heavy javelins called pilum. The scutum¸ or rectangular shield, was a modification of the Greek round shield. Roman armor, called lorica segmentata, was essentially derived from a kind of armor worn by gladiators in the ring; gladiators and gladiatorial games, a cultural carryover from Rome’s long dead ancient masters, the mysterious Etruscans.

But the true strength of the Roman legion was its unprecedented command and control of a legion and its subordinate formations within the legion. No other foe Rome would face in its five-hundred-year reign could match the maneuverability and resilience of a Roman legion. Not even the legendary phalanxes of Alexander’s ancestors could carry the day against a well-led, fully equipped, and properly supported Roman legion.

And for many within the skeletal shell that was the Ninth, their belief and firm faith in the bloody reputation of the cunning fox that was Decimus Virilis was unshakable. They knew what lay ahead of them. The real work of fighting a battle was about to begin. Somehow, knowing that Decimus, “The Lucky,” was in command, gave the men a sense of purpose, a surging sense of pride pounding in their chests. A sense of unrealistic invincibility.

IV

7 AD

Dalmatia

Hard fighting

When the attack came it was just as the sun’s growing intensity began to burn off the fog hanging stubbornly in the morning air. The panorama of the narrow valley began to materialize out of the thinning fog, revealing both the rugged terrain of the valley, and the rectangular masses of enemy infantry dressed in their various assortment of individual armor. Dalmatian tribesmen were not nearly as wealthy as their Greek cousins. When one might be encased in the full armor of a Greek warrior, five or six others of his kinsmen might be wearing various forms of leather armor, or no armor at all. But all gripped in their right hands the Greek sarissa¸ the eight-foot-long Grecian thrusting spear made famous by Greek armies all across the Mediterranean basin.

The first assault came along the northern slope of the hill. The slope offered the easiest access up the moderate-sized hill overlooking the road which ran through the middle of the valley. Two phalanxes of infantry, each rectangular box of men composed of eight ranks of infantry, numbering perhaps a thousand total, began making their way down the road and toward the northern slope in a slow, determined dance of death.

Decimus eyed the approaching enemy, holding his curved shield close to his body with one hand and firmly gripping his sword with the other. The breeze crept down the length of the valley, blowing the fog away in its path, and played with the black horse-hair plum of his tribune’s helm haphazardly. Shafts of sunlight cut through the evaporating fog, illuminating portions of the battlefield below, as well as segments of the legion’s defensive positions. Bright columns of yellow sunlight moved across the terrain slowly. One such shift drifted slowly up the hill and momentarily illuminated Decimus and his position, along with his servant, the silent Gnaeus at his side, before drifting away. But in those few seconds when the gods gifted the tribune with their light of favor, for lowly and superstitious Roman and Dalmatian both, the image of a warrior bathed in light was stunning to behold.

Fifty meters away from the defensive perimeter’s edge, the leading Dalmatian phalanx split in half, wide enough for a dozen horsemen to come galloping through, the riders whirling long ropes over their heads, each rope ending with the ugly mass of a grappling hook attached to it. They charged toward the wooden stakes driven into the ground just behind the low defensive trench the legion dug first when they began building camp. Decimus, seeing what was about to take place, stepped into the first rank of the cohort, his voice a powerful trumpet heard by all.

“First rank, pilum! Cut them down before they tear the palisades apart!”

Eighty legionnaires rose, lowered their shields, and hurled their stubby javelins before stepping back and squatting down and locking their shields together in a defensive stance again. The air in front of the first rank turned partially dark as the cloud of falling pilum fell like rain onto the horsemen. The results, for the horsemen, were devastating. Eight of the bareback riders fell from their mounts with multiple javelins buried into their chests and extremities. The remaining four had their mounts screaming in pain from the falling rain of death. They went mad from the pain, whirled on their haunches, and raced back toward friendly lines.

A cheer from the cohort, four hundred eighty voices full, rose into the clearing foggy morning with a raucous defiance. But the cheering did not last long. The first ranks of the Dalmatian spearmen came marching up to the rows of wooden stakes. With the sharp echoes of multiple voices repeating the same command, the enemy phalanx came to a sudden halt, round shields up to protect warriors in the second rank back to the sixth rank. The first rank, and most exposed spearmen, discarded their spears and began ripping apart the wooden palisades.

Decimus, hunched behind his shield, watched with a grim admiration. The commander of this enemy force knew the Ninth had not acquired its detachment of auxiliary bowmen. Without the century or two worth of bowmen—roughly eighty to one hundred sixty men pressing forward to hurl their deadly flights of arrows toward the enemy, the enemy was free to do as he pleased. Somehow the Dalmatian commander knew there was nothing his men could do to stop them from destroying the palisades without detaching a century of men or more to break the legion’s defensive lines and step forward to contest the issue. Breaking the defensive lines of the first rank of the cohort was the last thing Decimus would do.

Soon enough the real work of a legion’s life began when Dalmatian spearmen came marching up the hill in mass and plowed into the first ranks of the defending cohort. The resounding shudder of legionnaire shields crashing into lowered ranks of hundreds of spears cut through the morning air with a terrible snarl of martial fury. Followed, soon enough, with the curses and screams of men fighting for their lives.

Hard Roman training of using scutum and gladius in close combat situations consumed each legionnaire. Working as a well drilled machine, the Roman line of legionnaires began their bloody work with cold efficiency. With shields covering their bodies the men in the first Roman line found gaps in the wall of spears in front of them or cut through the massed steel of pikes aimed in their direction. They slipped inside the line of steel and began hacking away at the enemy at close range. The gladius was designed to be a thrusting sword. Not a slashing sword. Finding gaps between the enemy’s shields, Roman steel slipped in and wrought their bloody work. Soon the hill slope was awash in blood and falling bodies as badly trained Dalmatian spearmen fought valiantly with their superiorly trained foes.

For two hours the cutting and slashing of Roman steel with the Dalmatian mass of infantry was hot and fierce. The Roman ranks wavered and bent but never broke. The entire cohort pressed forward at times to lend support to their brethren in the first ranks of the formation. At the end of the two hours the ranks of the Dalmatian spearmen staggered, lurched back, and then broke entirely. Panic swept through the first Dalmatian phalanx and they fell back, dropping shields and spears, and turned to flee from the battlefield. Their disjointed withdrawal smashed head long into the second phalanx of spearmen directly behind them. Panic in their eyes and voices, the smell of a rout was like a disease which rapidly infected the second phalanx.

The officers of the second phalanx tried desperately to hold their men in formation. But it was for naught. More untrained Dalmatian tribesmen than seasoned soldier, they too turned and fled from the field as fast as their feet could carry them.

Again, from the voices of the legion, a wild cry of victory and defiance lifted toward the heavens. From the hills and forested slopes of the mountains surrounding the narrow valley the enemy watched in silence at the failure of their initial attack. Watched in hatred as the men of the Ninth raised their bloody swords, and their voices, toward the heavens in celebration.

Twice more the enemy marshaled its men and hurled themselves against the shields of their enemy. Bloody fighting. Cruel deaths. But both waves of Dalmatian infantry shattered like ocean waves breaking against unyielding rock and washed away into nothingness. Fortunately, late in the afternoon as the legion licked their wounds and watched across the valley floor at the gathering tide for a fourth assault, gray clouds filled with rumbling fury rubbed out the mountain tops surrounding them from view and began to descend into the valley. Within an hour a fierce rain filled with raw lightning and cracking thunder filled the air with a ferocity only nature could hurl at men.

The gods, being the pranksters they were, decided Roman steel and sinew had to endure the rawness of a wet, cold Dalmatian night without the comfort of a dry tent to dress their wounds, or hot food to calm their fears.