16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

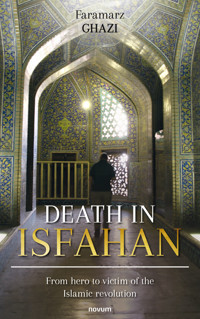

- Herausgeber: novum publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

At first, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlawi had a grand vision: to catapult Iran from a deep sleep into modernity. But free modern people did not fit his vision. When his subjects sought protection from the Shah's vision and police violence, they found it in the past, in Islam. Omid was one of the revolutionaries who overthrew the Shah in February 1979 and seized power. Now they worked with great zeal to realise their vision: to establish a theocracy with believers. They also failed. Omid realises that the new rulers want to use the Shah's methods to make the people compliant. Violence is used to silence dissenters. Disappointed, he turns away. Omid's fate stands for all Iranians who now want to live in a free and modern Iran.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

I

Don't blame the wheel of heaven!

Unlearn stubbornness and pride!

Do not see the celestial wheel as guilty!

It is inappropriate to rebuke a wise man.

Nasser Khosro (1004 to 1088)

1

"Brother Omid!"

Someone calls to him loudly from behind.

When Omid hears his name, his heart starts to race. Something is wrong. An electric current shoots through his body, blood floods his brain and his hair stands on end out of fear.

"Who iscalling me? Now, at this time of night?What doeshe want from me? And in this narrow, dark alley? How does the caller even know that I'm in Isfahan?"

Only his superior and the employee accompanying him know about his journey and the assignment. He is overcome by a strange feeling. Someone calls him and he immediately panics like hell. He feels as if his name is being called so that he can climb the steps to the gallows. "He addressed me as 'brother'. So is he an Islamist?" it flashes through his head.

"Nowadays, the term 'brother' or 'sister' is always better than 'comrade' or 'comrade'," his boss had once told him with a cynical undertone. At the time, Omid had shrugged his shoulders impassively. He didn't bother to think about why his new superior had so demonstratively slammed that at him in front of other colleagues. Was it an allusion to Omid's obscure past? Or an allusion to the fact that he was not fully trusted?

Nobody in his department addresses him as "brother". Everyone knows that he doesn't like this form of address, which is otherwise customary in the office. Omid made that clear early on.

The office, that was the intelligence service.

Omid started out in the department responsible for the internal security of the apparatus itself. Its task was to defend against possible infiltrations, but it also dealt with internal abuse of authority.

To fill the gaps after the dissolution of the Shah's secret service, an army of new agents was quickly recruited. Particular importance was attached to loyalty to the revolution, and recommendations from acquaintances were decisive. Specialist expertise was of secondary importance and it was not possible to check their professionalism due to time constraints.

Then Omid was transferred to another department. At their request. His job there was to investigate why the rift between the government and the intellectuals was widening inexorably. He only knew the head of the new department from hearsay. He only knew that Ali Sabeti had studied in America and had not been working for the secret service, which is organized as a ministry, for very long.

Omid didn't like him, but couldn't give a clear reason why. However, he found the new task appealing. He felt honored by the offer. Dealing with intellectuals was a challenge for him.

***

And so Omid was sent to Isfahan. A well-known writer had been found dead, and since then tensions had been rising dangerously beyond the city. The dead man was not just anyone. He was the country's best-known and loudest voice of protest. As is so often the case with mysterious cases, it would not remain just a news flash in the inside pages of the newspapers. That would not do this dead man justice.

Omid's superiors wanted answers. If the writer really had been murdered, someone had miscalculated and gone too far.

The Isfahan police were at a loss, unable to solve the case. A chain of mysterious events led to the investigation coming to nothing, and the public prosecutor's office showed no particular commitment. The highest preacher in Isfahan told the chief of police of his unease at the police's stubbornness in trying to solve the death, and the conservative circles committed to the revolution did not hide their joy at the death of the respected secular intellectual.

However, the government in Tehran was under growing pressure from public opinion. Day after day, the newspapers wrote about the writer. Alarmed by the mysterious circumstances of his death, they wanted to know more.

A street sweeper found him early one morning while sweeping a narrow alley. He immediately informed the police. It took a good hour for them to arrive. In the meantime, several people stood around the dead man. One resident almost reverently pulled a blanket over him. Adults asked the children, who had to walk past the dead man on their way to school, to walk faster. They grabbed the younger ones by the hand and prevented them from looking. Next to the victim leaning against the wall was an almost empty, colorless glass bottle without a label indicating the contents.

The police officers had to park away from the scene. They arrived on foot, a police officer and two young assistants who were doing their military service with the police. A few minutes later, three Red Crescent paramedics arrived with a stretcher. The policeman was wearing a blue uniform. A large gold-plated star shone on the epaulette, the badge of a commissioner. But his uniform looked a size too big, the wide trousers looked a bit shabby, which took away from his authority. The two assistants, dressed in khaki uniforms, asked the onlookers to take a few steps back so that the young inspector could begin his work.

The inspector approached the body. Slowly, he lifted the colorful and cheap blanket from the dead man's face. He was presumably in his early sixties, shaved and with a neatly trimmed moustache. So not a homeless person, as the inspector had assumed when he had been informed of the body's location.

He noticed something else. The dead man's skin looked yellow-brownish. He was probably not from Isfahan. Most people here have lighter skin. The inspector inspected the dead man's hands. The fingernails were cut and clean. The callus on the middle finger of the right hand was conspicuous. The victim must have written a lot, the inspector thought.

***

The police officer ascertained the death by the rigor mortis that had set in and the purple marks on the neck and face. This was confirmed by the Iranian Red Crescent rescue team. The face was slightly swollen. The police officers and rescue workers concluded that he had heart failure because of the blue lips. Perhaps alcohol poisoning, thought the inspector, looking at the bottle. He took his handkerchief and lifted the bottle. The contents smelled of alcohol. It irritated him that he couldn't smell any alcohol on the victim and that the bottle was standing upright next to the corpse. The scene seemed to have been prepared and was suspicious to him.

The inspector stood up, turned to the onlookers and asked if anyone knew anything about the dead man. No one answered. Only the street sweeper, holding a long broom made of broom weed in his hands, waved and mumbled something unintelligible. All that could be heard was the word "police". He probably meant that he had reported the find to the police.

The inspector nodded and asked him to come closer. He had never met the man in the neighborhood, he said, and he had never seen anyone else in the alley at this time of night. "Have you touched or changed anything here, such as putting the bottle down?" the inspector wanted to know.

He replied in the negative and added that he had called the man several times. When he didn't move, he gently poked his shoes with the broom handle to wake him up. "As he was leaning against the wall, I thought at first that he was asleep or had become nauseous," the street sweeper mumbled.

The clay walls were crumbling, so the asphalted alleyways had to be swept every other day. The street sweeper had swept everything except for a large semicircle around the dead man. As a result, there was still a thin layer of dust on the asphalt around the body, on which footprints were clearly visible. The inspector couldn't tell where they had come from, and he didn't check any further. He had no equipment with him, not even a camera.

The inspector picked up the bottle and smelled it repeatedly. It was clearly the usual raisin brandy, the production and consumption of which was prohibited. However, it is easy to obtain on the black market. He searched the dead man's pockets but found nothing, not even a bunch of keys, which should be standard equipment in every trouser pocket. He himself always had an annoying bunch of keys to carry.

"Nowadays, doors always have to be locked several times," thought the inspector. Yet there had been no such worries in the first few years after the 1979 revolution. His colleagues had once told him that theft was one of the areas that kept the police least busy.

He recalled that petty crime had increased during the time he had been accepted into the police academy. Just three years later, burglaries were already on the agenda. Special departments were set up and citizens had to be warned about burglaries via state radio. One piece of police advice at the time was: "Never leave your house alone, or make sure the doors are locked when you leave."

Additional locks were put on the front doors, windows were barred, walls were raised even higher and barbed wire or broken glass was added to act as a deterrent. Even in a big city like Isfahan, the inspector saw day after day how ugly the new houses looked, like countless small prisons.

Now the young detective was faced with a death. He didn't have much experience, even if the number of murders and violence in general showed an upward trend.

He also found no pen on the dead man.

He released the body. There was nothing more to find out.

The paramedics had left, so the commissioner's assistants placed the body on the stretcher, one threw the blanket back over it, and they carried it over to the hearse, which had arrived.

The inspector took the only object found at the site, the bottle, with him. He considered different versions of the case and thought about how he should write his report. The most important thing was to identify the dead man first. He suspected that he would soon find out. The dead man looked like a respected citizen.

The small crowd, at first with horrified and now more curious faces, gradually dispersed. They disappeared into their houses and slammed the doors behind them. The alley was empty and quiet again. Just like two hours before.

2

Omid had always wondered why Kermani was so important to the gentlemen up there.

Kermani was nothing more than an intellectual dissident, someone who dealt exclusively with Iranian culture and history and who taught as a guest lecturer at the Faculty of Persian Literature in Isfahan. He knew many poems of the old Persian writers and he gave anecdotes on every political event or on a politician's not exactly clever statement. Sometimes he was cynical, sometimes humorous.

He knew the psyche of his fellow countrymen. If he hadn't been systematically harassed, he wouldn't have screamed and protested for help.

Years before the Islamic Revolution, he wrote a long poem in which he declared his belief in a world without a god:

"I am godless, yes, I say it out loud, I do not recognize this God,

Worshipping him gives me no honor,

He is prone to rage, he seduces and deceives his creatures with houris in paradise and threatens torture in his hell,

I do not worship this beast,

I am not afraid and fear no punishment."

He was later to focus on religious topics.

But I would never have classified him asdangerous, Omid said to himself.

Now he's dead, and I'm probably going to be wiped out too. Why then, asks Omid, who is now standing in the dark alley. His pursuer is on his mind at any moment.

***

The following day it was already known that the deceased was none other than the well-known dissident and writer Saied Kermani, who had been reported missing by his family three days earlier.

His death could not have been natural, the liberal newspapers, which reported the death of the sixty-two-year-old Kermani on the front page, were unanimous in their opinion. For them, the bottle of alcohol next to the dead man was proof that the murderer or murderers wanted to accuse Kermani of drinking alcohol and thus try to defame him.

Omid knew the deceased very well. He had had long and in-depth conversations with him. No one else was more familiar with the Kermani case than Omid Hadian. That is why his superiors had tasked him with investigating the case.

He knew that the secret service, known as the Ministry of Information, had taken over the investigation on the express orders of the President of the Islamic Republic and that the police had been released from investigating. The president felt compelled by public pressure to show a willingness to investigate. The president personally appreciated Kermani's literary work and had even worried about his life.

Kermani's death made waves, both at home and abroad. Major international media also reported on the writer's mysterious death. The president used the pressure of public opinion as an excuse to intervene in the case. However, he did not want to offer his conservative opponents, the hardliners, a target.

***

Omid had arrived in Isfahan. He stepped out of the hotel, but didn't want to take a cab. A car stopped at his feet. At the wheel was a man in his mid-forties. He was probably driving passengers after work to supplement his meagre income. Omid waved him off and let him drive on. He didn't want to take the first one. "Maybe he was even waiting for me," it occurred to him.

The next car stopped in a moment. This time an older man was driving an old Citroën 2CV. Omid stuck his head into the car through the open window and quietly told him the address. He never spoke loudly and was always careful not to let anyone else overhear. The driver told him the price. It was a deal. Omid got into the back of the duck. They drove to the street that had once been cut like a swathe through the old quarter of Isfahan in a modernization push.

Now he was standing in the narrow alleyway and someone called out to him: "Brother Omid". As he quickly reconstructed the moments leading up to the shout, he thought: "Up until that point, nothing remarkable had happened."

He got off at the main road and walked into the old town. He passed an alley that resembled an avenue. A narrow path ran along both sides, with a wide stream up to two meters deep running between them, lined with all kinds of trees, mulberry trees and shrubs with figs, as well as wild plum trees and weeping willows. Whatever sprouted from the ground by chance was allowed to flourish. Any greenery is welcome.

He turned into a side street. From then on, cars could hardly drive through the narrow streets. Only local residents were allowed to reach their houses by car. There were small parking spaces for a few cars every few hundred meters. Usually there had been a house there that had been abandoned and demolished to make room for cars and motorcycles.

He passed a few stores. First of all, that of a carpet maker. An old man with a knitted cap and thick glasses worked under a pale light. There was no one else in the small store, which was crammed full of carpets and carpet remnants. There wouldn't have been room for another person.

Right next door was a coppersmith. Three young lads worked in the store. Or was it four? A fire was blazing at the back, a worker was galvanizing the insides of copper dishes. Omid recapitulated the scene like this:

"None of them paid any attention to the passers-by. They were very busy with their work, which requires a high level of concentration anyway. The older man, probably the master craftsman and owner of the small workshop, was hammering away at a huge copper pot with a constant rhythm."

You can prepare rice or stew for fifty people in such a huge pot. They are used on religious occasions. Several pots of this size are placed on a wood fire. What is cooked is distributed to the believers. Now Muharram, the month of mourning for the Shiites, was approaching, so the coppersmith had to work late into the evening to fulfill his orders.

A sooty portrait of the leader of the Islamic Revolution hung in his store window. As if to show his loyalty to the system. The portrait of the leader once adorned the walls of every bazaar in the country. Over time, however, it disappeared from the stores.

Half-torn or smeared pictures were left hanging in the stores, revealing the dwindling sympathy for this politician and man of God. You only had to walk through the bazaars, you no longer needed statistics to get an impression of how much people agreed - or disagreed - with his policies.

Then the bakery. Men and women stood in two separate queues. Many were waiting to buy the "sangak", the popular wholemeal flatbread prepared on hot gravel. The chador-clad women formed a black mass with no visible dividing lines. It was difficult to tell how many there were. Three or four boys scurried around in the crowd as if they didn't know which queue they belonged to.

Two men stood out. One was slightly stocky, apparently an ordinary civil servant or teacher. The second was young, had a full beard and an athletic figure. Omid couldn't see a face, only his profile. He noticed a large hooked nose, nothing more. He seemed to be the last in line. So he would have to wait at least another fifteen minutes before he could take the thin flatbread that the baker tossed onto the counter one by one.

"That could have been the man who's after me," Omid thought. Because he didn't quite fit the picture in front of the bakery. Men don't like to queue there. As a rule, women or children take on the task of buying fresh bread, even if the fathers of the family greatly appreciate enjoying bread warm from the oven during the evening meal. Women also use buying bread as an opportunity to get out of their homes and exchange news about the neighborhood with other women.

***

Omid had a remarkable visual memory. But the young, athletic man did not look familiar to him. As Omid walked past him, the man hastily reached into his jacket pocket. Omid had stored this in his head. But he didn't think anything of it. Maybe he just wanted to pull out his wallet.

But perhaps this movement has another explanation in hindsight.

Because he was now being called by his name. A hundred meters away from the stores, where the houses are even denser and the alleys even narrower, in a narrow, rather long alley with many bends and side alleys.

It was around 8 o'clock in the evening.

In earlier years, donkeys and mules trotted through this extensive, impressive maze, carrying all kinds of loads. In the early morning, you would have heard men offering their wares. "Fresh potatoes," shouted one loudly. Minutes later, a mule loaded with onions came by. Another mobile vendor praised his fresh herbs, without which nothing works in Iranian cuisine. The housewives knew the order. They had small change and a basket ready to get what they needed from the supermarket on four legs.

But then bicycles and finally motorcycles replaced the four-legged friends.

Only the ornately decorated doors, which here become a long art gallery, tell passers-by where a new house begins in the long, uniformly light brown wall. Windows rarely interrupt the wall, making it difficult to guess whether a house is actually inhabited. Omid could clearly hear his own footsteps, even though he was wearing rubber soles.

Sometimes the alley was two meters wide, sometimes two and a half meters. The short side alleys were even narrower at one meter at best. Sometimes a small indentation appeared unexpectedly, with no clear purpose. Now and again a ceiling hung over the alleyway, as if a room had been built over it, perhaps for another child. In places you walked under wooden beams, but they were high enough so that you didn't have to duck.

***

The houses in the labyrinth do not have a fixed plan. Their floor plan cannot be determined exactly. They may consist of one or two rooms, which later became three, with a kitchen and a toilet. The latter is usually located a little out of the way in the courtyard, if there is one, otherwise in the nooks and crannies of the house, because of the smells and noises.

The walls and ceilings have no sharp corners or edges, as if the Spanish master builder Gaudi could have designed them. From a bird's eye view, the old town must look like a sprawling ants' nest. Except that it was built flat and wide, without architects and without a building authority. The people knew what they were doing. Their traditional building technique has not changed over time. They mixed clay with straw. The building material has proven to be a good insulator, so the narrow, shady alleyways are cooler in the hot months than the wide streets in the new town.

Omid had planned to interview the writer's brother, Mahmud Kermani, today. He lived at the very end of the labyrinth. He had already had long conversations with him. Now new questions had arisen in the course of his investigation. He had to try to give contours to the still blurred picture of Kermani's death.

He had memorized how to reach the house. Twice to the right, then left, past two side alleys, then the illuminated minaret of the main mosque would be visible, another left there and the third door on the left again. A hundred-watt light bulb had to be burning here, as was the case above almost every front door.

There was still a long way to go.

3

Then the voice that had called his name. Omid did not turn around. He didn't dare, but he didn't stop either. The man behind him was certainly aware that his steps were out of rhythm for a moment. That was normal; anyone would have reacted if they had heard a loud voice in the empty alleyway at this time of night.

What wasn't running through Omid's head? "A fairly young voice, maybe the man just wanted to verify my identity. It could be someone who knows more about the case and wants to share it with me." Omid asked himself questions. He had no answers that were important for his actions.

He walked past many doors and thought about suddenly stopping and knocking on a random door. Maybe someone would be at home and would open the door for him.

Most old wooden doors are fitted with two iron or brass door knockers, one long and one circular. If he knocked with the long knocker, he would let the residents know that a man was at the door. If there was no man at home, the women in the house would generally not open the door for him. Using both knockers at the same time would be useless. Nobody would take such a knock seriously.

Omid's steps quickened. He was almost running. He couldn't hear the man behind him. The blood circulated in his ears as loudly as a raging river. Omid was sure that the man was also quickening his pace.

He wished he could climb up a wall like a cat and seek refuge in a house. That saved his life once.

***

It was during a protest march against the Shah. An officer from the Shah's feared guard had identified Omid as the ringleader and decided to arrest him. When Omid noticed a pair of eyes fixated on him, he slowly withdrew from the front ranks of the demonstrators. He ran into a narrow alley and began to run as fast as he could. The officer ran after him just as fast with his gun drawn. His chances of escaping him were not great. As he turned into another side alley, he scaled a wall without a second thought and ended up in the small yard of a family. A small child, four or five years old, was playing peacefully on his plastic bicycle.

It stared at Omid in amazement with its big eyes, but said nothing. The boy was surprised. Had someone fallen from the sky? Is it an angel? Can it really fly?

Omid smiled at him and held his index finger in front of his mouth. The boy liked the gesture and took it as a game. Then there was a loud knocking on other doors in the alley. No one opened them for the officer. They had a feeling for such cases.

Omid had escaped back then. But today, almost twenty years later with a slight tummy bulge, that was an unthinkable undertaking.

***

Then let him call me again if he wants to tell me anything about the case, thought Omid. But no one called and he now sensed that his life was in danger.

He inconspicuously reached into his jacket pocket, took out his weapon and disarmed it. It was a light short-barrel revolver, an Arminius HW22, which was not usually intended for police use. Omid always wanted to carry a light weapon that would not stand out in his jacket pocket. He didn't want to wear a gun belt. Then he could just stick the badge on his forehead, he had always thought.

Now it was too late to regret it. If the pursuer had a 9-millimeter Smith & Wesson long-barreled pistol, he would have been shot. Maybe that's why he kept a distance of 30 to 40 meters. Omid had estimated the loud call at this distance. Consequently, the pursuer knew the range of Omid's revolver. He must be a professional and not an opposition dilettante.

Omid had already survived an assassination attempt. That was a long time ago. Back then, as a young revolutionary, he had the task of conducting interrogations in prisons and trying to convince prisoners of various political persuasions of the revolution. It was a time when Omid and his cronies were still firmly convinced of their world view. They saw themselves crystal clear and unshakeably on the right side of history. They thought that all they had to do was talk to their opponents, especially the young ones, who tended to be troublemakers and did not bow to the new rulers, and educate them. Then they too would be convinced.

However, there was an underground Islamic organization that fought against the new leadership. They called themselves the People's Mujahideen. Young people, especially from conservative families and smaller towns, joined them. To show its supporters in the prisons that it was still capable of action and strong, the organization ordered Omid to be eliminated.

The plan went wrong and the two assassins were unable to carry out their mission.

Omid was driving his car to Evin Prison in the north of Tehran that day. He noticed a motorcycle following him in his rear-view mirror. Omid drove very carefully at the time, constantly checking all three mirrors. He knew how the People's Mujahideen liquidated their opponents. They rode in pairs on a motorcycle, with the shooter sitting in the back. The driver now wore glasses. As most of them were still schoolchildren and students, they wore goggles more often than other motorcyclists. This and their conspicuously calm riding style caught Omid's eye.

Omid kept an eye on them, driving a little slower and leaving just enough space on the left for a motorcycle. It was an invitation to the assassins, and they fell for it. The motorcycle caught up and was only a meter behind Omid. He could no longer see them in the rear-view mirror. The gunman had probably taken the pistol out of his pocket and removed the safety. Omid didn't see it, but it had to be the case.

He heard the motorcycle traveling at the same speed as him. Now he pressed lightly on the gas pedal and the motorcyclist did the same. Then Omid suddenly hit the brakes and turned the steering wheel to the left. The motorcycle hit the left mudguard and flew onto the road. Omid jumped out of the car and drew his revolver. The thwarted shooter freed himself from the prone motorcycle in a split second and disappeared into the busy street. But he had lost his gun, which was lying on the asphalt.

However, the driver was trapped under the motorcycle and appeared to be somewhat dazed. His broken glasses were flung a few meters away. Omid pointed his revolver at him, shouting loudly and threateningly: "Don't move! Stay on the ground!" The traffic came to a standstill and in no time at all a crowd of curious passers-by and shopkeepers formed around the two of them. They quickly guessed what it was all about, the image was familiar. In the big cities, it was repeated several times a day. The People's Mujahideen had launched a campaign of terror and had already struck down many active supporters of the regime.

The onlookers observed the scene with mixed feelings. They neither approved of the terrorist attacks nor the unrestrained violence with which the new regime took action against its opponents. They wanted nothing more than peace at last. Three years had passed since the upheaval and there was no end in sight to the spiral of violence.

Omid waited silently, the people around him also remained silent. No one said anything. Some eyes showed compassion for the boy trapped under the motorcycle. His immediate fate was not hard to guess: a short trial followed by execution. That was the verdict for the armed uprising against the state.

Omid waited until the police arrived and picked up the skinny boy, who was about twenty years old, and the motorcycle. He put up no resistance, stood up, limped slightly and got into the police car with his head down. He had wanted to change the world. He didn't succeed, and now he didn't want to know anything more about his dreams. The world wasn't even worth a farewell glance to him.

Just as the onlookers had watched the event with mixed feelings, Omid now felt the same. He was impressed by the boy's attitude and found something bold and heroic in it. But he had no idea what the young man was thinking about when he was taken away.

Did he feel like a little bird in the clutches of a hawk? In any case, he could not read any fear of the impending execution from his face. You can't see fear or pain in the eyes of a partridge in the claws of a hawk. Was the boy in adrenaline shock? Perhaps he was thinking about the past and what had been lost in his life, but not about the future, because he knew exactly what awaited him.

Omid felt a pleasant sense of victory over this young stranger, but not a deep satisfaction. Something didn't sit well with him. The incident reminded him of the games from his childhood. He had often played cops and robbers with his brother and other children from the neighborhood. That was a game back then. But here it ended in death for the loser. The loser is physically eliminated. He will never be a player again and there will never be another game for him.

***

Omid ran on and was covered in sweat. It will take an eternity to get to Kermani's brother's house, he thought.

So will the game go on after all? Will he be the winner this time too and celebrate his life? Or will he be cut off and taken out of circulation for good because he knows too much and has stuck his nose where it doesn't belong?

He didn't want to say goodbye that easily. He thought of his wife and two children. What would happen to them if he lost the game now? He still had a lot planned for his life. He had firmly resolved to write his memoirs. Things had gone up and down, he had met famous people and had exciting conversations with them. He definitely wanted to write all this down. For history. He felt very obliged to do so.

These thoughts worried him even more.

The fact that he survived the assassination attempt strengthened his standing and reputation among his comrades. The prison governor congratulated him the following day, and the inmates now feared him more than ever. That same day, the news of the failed attack had spread throughout the prison.

Since that day, Omid has never left the house without his HW22. It gave him a certain sense of security, with a little superstition thrown in. Because he knew very well what the weapon was good for: it was a small caliber for short distances.

Being somewhat superstitious was not at all abnormal in those days, perhaps even somewhat fashionable. The more people believed in metaphysical powers (or at least pretended to), the closer they were to the revolution. On Omid's way to work, a huge plaque read: "Iran is the land of lovers and not of the wise." It was a quote from an influential Ayatollah. At first glance, however, it sounds crazy in the Islamic Republic. However, the Ayatollah wanted to express that God is perceived with the heart and not with the mind.

A pinch less sense was definitely "in". Omid told the story of the gun with an undercurrent of pride among his confidants. He emphasized his belief in the revolver and implied: "I may be clever, but don't worry, I'm also a bit simple."

Those who were good at this game rose more easily in the new apparatus. Many rose through the ranks, not only genuine revolutionaries. Their opponents also knew how to infiltrate the new system, and in this way they reached key positions in the security organs. Everyone was suspected of something, without exception, and they too had to constantly prove their loyalty.

***

But now, in the narrow streets of Isfahan's old town, the moment of truth had arrived for Omid. He wanted a suitable Smith & Wesson or a Beretta, anything but this toy! The belief that his revolver had powers that the technical data sheet concealed had long since evaporated. He was faced with the bare facts: He had little chance against a long-barreled weapon with the short range and miserable accuracy of his revolver.

Actually, he had always suspected that the story about the imaginary metaphysical powers was more of a joke. But he suppressed it and sometimes even hoped it was true after all. However, this superstitious thinking persisted throughout society, especially in the first months and years after the 1979 revolution. It took years for society to gradually mature, and not everyone went along with this development.

In Omid's case, it was a mixture of hypocrisy and immaturity for a long time. How else could he have held on for so long? He was forced to put on this mask. Over time, it was no longer necessary or possible to take the mask off every evening. It was firmly attached to his face. At some point, he couldn't remember when it was, he no longer even knew who he really was.

He did everything he could to avoid being fired. Because it was no longer possible to leave the apparatus. He was too well known in his own ranks and too disreputable among the opposition. Without his gun and badge, he would have been fair game. Anyone would have killed him immediately, whether from the armed cells of the opposition or even from within the security apparatus. He had enough enemies.

***

Omid Hadian was a high-ranking, competent civil servant, inscrutable and arrogant. His past did not fit the stereotype of an Islamic revolutionary. He was well-read, knew books on Marxism and by Islamic scholars. His files revealed that during his time in prison the year before the revolution, he had got on well with prisoners of all political persuasions and openly debated the revolution and the future of the country with them. It was also noted that he did not take the daily prayers of the faithful very seriously.

That made him neither predictable nor transparent for many in the apparatus. And now in Isfahan, does anyone here want to settle accounts with him?

It would be easier, he thought, to withdraw the Kermani file from him again or to suspend him, without even needing a credible justification. On the other hand, he knew that many things in the office were neither reasonable nor logical. He had no explanation for much of it. The apparatus consisted of a mixture of envy, political intrigue, suspicion and even normal detective work.

As he continued his investigations in Isfahan, he began to suspect that a team of professionals recruited from the country's security apparatus was operating independently of him. He had no idea who was behind it and who would be giving the orders. He reported his suspicions to his superior, who in turn reported directly to the minister.

From that day on, strange things happened. Until today, when someone shouted: "Brother Omid!"

4

Omid often thought that his life was a chain of coincidences, beyond his control and at the mercy of fate. Like a piece of wood on the waves of a raging current. When he looked back on his career, he perceived fog - the fog that shrouds revolutionary zeal and frenzy. Without knowing where his steps were taking him, he sank deeper and deeper into a swamp of violence and atrocities. At the abyss of this stinking, stagnant water, at the end of his unplanned transformation, he did not recognize himself.

During his life, he had often wrestled with himself, but the maelstrom of fast-moving events often left him no opportunity for reflection. And so he lost more than a few battles against his almost unstoppable fate.

People don't just want to observe the big story from a safe distance. They make history themselves, and Omid also wanted to fulfill his duty as a human being. He did not succeed. Omid probably tried to use this reflection to justify his actions. However, he rarely managed to convince himself. And so his conscience hardly stopped plaguing him.

In life, you often make small decisions that seem completely harmless and insignificant at first glance. You don't give them much thought. But then a seemingly banal selection of options shapes your life. They come together, pile up, and suddenly you find yourself in a place where you don't want to be, and life inevitably takes an unwanted turn.

***

And so he developed a gimmick in daydreams. He looked at his personal fate and the course of events in his life. He called it the what-if game, and he played through various possibilities and situations in his life. He also imagined chain reactions, i.e. a conscious decision in everyday life that led to a path that he had not planned, but which was obviously destined for him.

He had no explanation for this "destiny" of his life. If it was based on a divine destiny, then I should feel good about it, Omid thought. After all, God, he was taught by faith, wanted the well-being of his creatures. But that was not the case.

Then he tried to simply delete or remove moments from his life. That made no sense. Either the tower would collapse or the chain would break, in other words, his development as a human being would stop or there would no longer be any logic in his life.

Many people say to themselves: "I did not choose this world, nor did I make it."This is what the poet and philosopher Omar Khayyam has been teaching Iranians for centuries:

"Oh heart, the world is nothing but shadows and appearances

Why are you torturing yourself in endless pain?"

However, there are always enough people who do not comply, who do not accept the rules of this "new world", the world after the revolution, or who do not adapt. They are imprisoned, die, are killed because they defy the new order and the new view of the world, which they find unacceptable. Just as Omid did to the old system.

Omid refused to submit to a "senseless" fate. At the end of each game, he was completely confused and disoriented. He could no longer draw clear lines for his actions and always ended up back where he was. This happened very often because he no longer knew what was good and what was bad, because he no longer knew which form of life was still desirable for him at all.

He felt weak and powerless in the face of his fate. He didn't have the courage to change the rules of the game, to introduce different values and standards for his decisions. He found himself more and more at odds with himself and his life.

In all the games he tried to avoid an event that burdened his soul the most; always in vain.

***

He shouldn't have entered that room. He should have simply turned around and calmly walked back down the stairs he had hastily climbed. It was a few seconds that basically ruined his life.

Omid was more inclined towards theoretical discourse. Even if he enthusiastically affirmed revolutionary violence, he did not see himself as a bearer of this revolutionary violence. He avoided violence, having suffered from it for years as a child. Like thousands of other young men, he had taken up arms during the few days of unrest, at the end of which one of the supposedly strongest armies in the world melted away like ice under the hot rays of the sun.

In the last days of the monarchy, only a few barracks throughout the country still offered resistance. One was in the east of Tehran and belonged to the air force. In other places, the soldiers had laid down their weapons, taken off their uniforms and deserted. They either ran home or joined the revolution. This was preceded by the fact that the armed forces had long since surrendered morally.

Omid arrived at the barracks with a revolver that he had captured the day before in a police station that had been stormed. A friend met him on the street and they drove there in his car. The barracks gates were closed. From 200 meters away, they could see that the guard posts were empty. Shots were fired sporadically. Neither the shooter nor the target were recognizable.

Even after dark, there were no lights on in the two-storey barrack buildings, in front of which ran a wide street. Water channels ran along both sides of the street to irrigate the trees that separated the street from the sidewalk. They had dried up and no longer carried any water. However, the old and magnificent plane trees on both sides of the street were still witnesses to a time when the canals still carried water. Back then, the barracks were on the edge of the city, which was growing inexorably. Today it is surrounded by many houses in a densely populated, rather poor residential area.

The houses were also two storeys high. They were all built with brick, visibly with little money. There was no decoration, the houses were left unplastered. One rectangular box followed the next. On almost all of the flat roofs were washing lines and television aerials. There was no shortage of this standard equipment.

***

The young men prepared themselves for a prolonged battle and began to take precautions. Those with more experience brought sandbags and barricaded the surrounding streets. A Citroën Dyane was overturned in the middle of the road. In less than an hour, the residents managed to gather what they could for the battle. Everyone helped however they could. Women took over the supply of hot tea and cookies for the fighters in the cold February night.

Only a few had G3 assault rifles, so they decided to wait out the night and storm the barracks only after the reinforcements had arrived.

The decision was finally made at the barricade where Omid was standing. More shots could be heard in the distance. So there was fighting in other corners of the huge complex. At first it seemed pointless to try to storm the main gate with just a handful of G3 rifles and a few handguns. But in the middle of the night, as the cold ate through their bones, a dozen of the impatient young revolutionaries were ready to attack.