6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

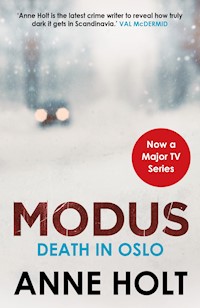

The third instalment in the JOHANNE VIK series, from the reigning queen of Scandinavian crime writing, Anne Holt. When Helen Barclay becomes the first female US president, the whole world takes notice. And unfortunately for President Barclay, one man takes very particular notice. He knows her darkest secret, buried for over twenty years. And not only does he have the power to destroy everything she's worked for, but he also has the ultimate motive. Unfortunately for the FBI and the Norwegian police, nobody knows about this when Helen Barclay chooses to visit Norway for her first state visit. But when she goes missing from a locked, heavily secured bedroom, they are forced - unwillingly - to work together to find her. Has she been kidnapped? Murdered? Can the US president really just disappear into thin air...?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

DEATH IN OSLO

ANNE HOLT spent two years working for the Oslo Police Department before founding her own law firm and serving as Norway’s Minister for Justice during 1996–1997. Her first book was published in 1993 and she has subsequently developed two series: the Hanne Wilhelmsen series and the Johanne Vik series. Both are published by Corvus.

ALSO BY ANNE HOLT

THE JOHANNE VIK SERIES:PUNISHMENTTHE FINAL MURDERFEAR NOT

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:THE BLIND GODDESSBLESSED ARE THOSE THAT THIRSTDEATH OF THE DEMONTHE LION’S MOUTHDEAD JOKERWITHOUT ECHOTHE TRUTH BEYOND1222

DEATH IN OSLO

Anne Holt

Translated by Kari Dickson

First published in the English language in Great Britain in 2009 by Sphere,an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group.

This edition published in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Originally published in Norwegian as Presidentens valg in 2006by Piratforlaget AS, Postbooks 2318 Solli, 0201 Oslo.

Published by agreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

Copyright © 2006, Anne Holt.Translation copyright © 2009, Kari Dickson.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library.

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-85789-435-9Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-615-6

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Thursday 20 January 2005

I

II

III

IV

Monday 16 May 2005

I

II

Tuesday 17 May 2005

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

Wednesday 18 May 2005

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

Thursday 19 May 2005

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

Friday 20 May 2005

I

Author’s postscript

To Amalie Farmen Holt,my champion,the apple of my eye, who is growing up

THURSDAY 20 JANUARY 2005

I

Igot away with it. The thought made her pause a moment. The old man in front of her lowered his eyes. His ravaged face was turning blue in the January cold. Helen Lardahl Bentley took a deep breath and finally echoed the words the man had asked her to repeat:

‘I do solemnly swear . . .’

Three generations of deeply religious Lardahls had worn illegible the print in the century-old leather-bound Bible. Well hidden behind the Lutheran façade of success, Helen Lardahl Bentley was in fact a sceptic, and therefore preferred to take the oath with her right hand resting on something she at least could wholeheartedly believe in: her own family history.

‘. . . that I will faithfully execute . . .’

She tried to hold his eye. She wanted to stare at the Chief Justice, just as everyone else was staring at her – the enormous crowd that stood shivering in the winter sun. The demonstrators were too far from the podium to be heard, but she knew they were chanting, ‘Traitor! Traitor!’ over and over, until the words were drowned out by the steel doors of the special armoured vehicles that the police had rolled into position early that morning.

‘. . . the office of the President of the United States . . .’

The whole world was watching Helen Lardahl Bentley. They watched her with hate or admiration, with curiosity or suspicion, and perhaps, in the quieter corners of the world, with indifference. For those few seemingly never-ending minutes, she was at the centre of the universe, caught in the crossfire of hundreds of TV cameras, and she must not, would not think about it.

Not now, not ever.

She pressed her hand even harder on the Bible and lifted her chin a touch.

‘. . . and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.’

The crowd cheered. The demonstrators were removed. The guests on the podium gave her congratulatory smiles, some heartfelt, some reserved. Friends and critics, colleagues, family, and the odd enemy who had never wished her well all mouthed the same word, silently or with loud joy: ‘Congratulations!’

Again she felt a flicker of the fear she had repressed for over twenty years. And then, only seconds into her office as the forty-fourth president of the United States of America, Helen Lardahl Bentley straightened her back, ran a determined hand through her hair, and looking out over the crowd, decided once and for all:

I got away with it and it’s time I finally forgot.

II

The paintings were certainly not beautiful. He did not care for one in particular. It made him feel seasick. When he leant in close to the canvas, he saw that the wavy yellow and orange strokes had cracked into an infinite web of tiny fine lines, like camel dung in the baking sun. He was tempted to stroke his fingers over the grotesque, screaming mouth, but he didn’t. The painting had already been damaged in transport. The railings to the right of the agonised figure now had a sad fringe of threads that curved out into the room.

Getting someone to repair the large tear was out of the question, as it would require an expert. And the very reason that these paintings were now hanging in one of Abdallah al-Rahman’s more modest palaces on the outskirts of Riyadh was that he always avoided experts, whenever possible. He believed in honest handicraft. He had never seen the point in using a motor saw when a simple knife would do. The paintings had been stolen from a poorly secured museum in the Norwegian capital. He had no idea who had stolen them or who had handled them on their journey to this windowless gym. He didn’t need to know who these petty criminals were; they would no doubt end up in prison in their respective countries without being able to say anything of any real consequence as to the whereabouts of the paintings.

Abdallah al-Rahman preferred the female figure, though there was something repulsive about her too. Even after more than sixteen years in the West, ten of which he had spent in prestigious schools in England and the US, he was still disgusted by the woman’s bare breasts and the vulgar way in which she offered herself up, indifferent and licentious at the same time.

He turned away. All he had on was a pair of wide white shorts. He stepped back up on to the treadmill, barefoot, and picked up the remote control. The belt accelerated. Sound was coming from the speakers on either side of the colossal plasma TV screen on the opposite wall:

‘. . . protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.’

He simply could not understand it. When Helen Lardahl Bentley had been a senator, he had been impressed by the woman’s courage. Having achieved the third highest grades in her year at the prestigious Vassar College, the short-sighted, plump Helen Lardahl had then fast-tracked to a PhD at Harvard. By the time she was forty, she was well married and had been made a partner in the sixth largest law firm in the US, which in itself demonstrated extraordinary competence and a healthy dose of cynicism and intelligence. She was also slim, blonde and without glasses, which was smart too.

But to stand as presidential candidate was downright arrogant.

And now she had been elected, blessed and sworn in.

Abdallah al-Rahman smiled as he increased the speed of the treadmill with one push of a button. The hard skin on the bottom of his feet burned on the rubber belt. He increased the speed again, right up to his pain threshold.

‘It’s just incredible,’ he groaned in perfect American, secure in the knowledge that no one in the whole world would hear him through the metre-thick walls and the triple-insulated door. ‘She actually thinks she’s got away with it!’

III

‘An historic moment,’ Johanne Vik said, and folded her hands, as if she felt obliged to say a prayer for the new president of the United States. The woman in the wheelchair smiled, but said nothing.

‘No one can say that that isn’t progress,’ Johanne continued. ‘After forty-three men in succession . . . finally a female president!’

‘. . . the office of the President of the United States . . .’

‘You have to agree that it’s quite something,’ Johanne insisted, her eyes glued to the TV screen again. ‘I actually thought they’d elect an Afro-American before they accepted a woman in office.’

‘Next time round it will be Condoleezza Rice,’ the other woman said. ‘Two birds with one stone.’

Not that that would be much progress, she thought to herself. White, yellow, black or red, man or woman, the post of American president was male, no matter what the pigmentation or sex of the person was.

‘It’s not Helen Bentley’s feminine qualities that have got her to where she is,’ she said slowly, bordering on disinterested. ‘And definitely not Condoleezza Rice’s black heritage. Within four years they cave in. And that’s neither minority-friendly nor feminine.’

‘That’s pretty—’

‘What makes those women impressive is not their femininity or their slave heritage. They’ll milk it, of course, for all it’s worth. But what’s really impressive is . . .’

She grimaced and tried to sit up straight in the wheelchair.

‘Is something wrong?’ Johanne asked.

‘No. What is impressive is that . . .’

She braced her arms against the armrests, lifted herself and twisted her body slightly closer to the back of the chair. Then she absent-mindedly smoothed her sweater down over her chest.

‘. . . they must have decided bloody early on,’ she said finally.

‘I don’t understand . . .’

‘To work so hard. To be so clever. Never to do anything wrong. Never to make mistakes. Never, never to be caught with their trousers down. In fact, it’s totally unbelievable.’

‘But there’s always something . . . some little secret . . . Even the deeply religious George W had—’

The woman in the wheelchair lit up with a sudden smile and turned towards the living room door. A small girl of about eighteen months peeked guiltily round the door. The woman held out her hand.

‘Come here, sweetheart. You should be asleep.’

‘Does she manage to get out of the cot by herself?’ Johanne asked with some concern.

‘She goes to sleep in our bed. Come here, Ida!’

The child padded over the floor and let herself be lifted up on to the woman’s lap. Her black hair curled over her round cheeks and her eyes were ice blue, with a clear black ring round the iris. The little girl gave the guest a shy smile of recognition and then snuggled down.

‘It’s strange that she looks so like you,’ Johanne said, leaning forward and stroking the girl’s soft cheek with the back of her hand.

‘Only the eyes,’ the other woman replied. ‘It’s the colour. People are always deceived by the colour. Of the eyes.’

Once again they were silent.

In Washington DC, the people exhaled grey steam in the harsh January light. The Chief Justice was helped down from the podium; from the back he looked like a sorcerer as he was led gently indoors. The newly elected president was bare-headed and smiled broadly as she pulled her pale pink coat closer.

In Oslo, evening was advancing stealthily outside the windows in Krusesgate and the streets were wet and free of snow.

An odd-looking character came into the large living room. She limped, dragging one foot behind her, like the caricature of a villain in an old-fashioned film. Her hair was tired and thin and looked like a bird’s nest. Her legs resembled two pencils and went straight down from under her apron into a pair of tartan slippers.

‘That girl should’ve been in her bed ages ago,’ she muttered without saying hello. ‘Nothin’ gets done right in this house. She should sleep in her own bed, I’ve said it a thousand million times. Come over here, my princess.’

Without waiting for the woman in the wheelchair or the little girl to respond, she scooped the child up on to her difficult hip and limped back the way she had come.

‘Wish I had a woman-who-does like her,’ Johanne sighed.

‘It has its advantages.’

They sat in silence again. CNN switched between various commentators, interspersed with clips from the podium, where the elite gathering of politicians had admitted defeat in the face of the cold and were leaving to prepare themselves for the greatest swearing-in celebrations the US capital had ever seen. The Democrats had achieved their three goals. They had beaten a president who was up for re-election, which was a feat in itself. They had won by a greater margin than they had dared to hope for. And they had won with a woman at the helm. None of these facts were to be underplayed. Pictures of Hollywood stars who had already arrived in town or who were expected in the course of the afternoon flickered on the screen. The entire weekend was to be filled with celebrations and fireworks. Madam President would go from one party to the next, receiving praise and giving endless thanks to her helpers, and would undoubtedly change into an array of outfits along the way. And in between it all, she would reward those worthy of reward with posts and positions, compare campaign efforts and financial donations, assess loyalty and measure ability, disappoint many and please a few, just as forty-three men had done before her in the course of the nation’s 230 years of history.

‘Do you think you can sleep after something like that?’

‘Sorry?’

‘Do you think she’ll be able to sleep tonight?’ Johanne asked.

‘You are funny.’ The other woman smiled. ‘Of course she’ll be able to sleep. You don’t get to where she is without sleeping. She’s a fighter, Johanne. Don’t let her neat figure and feminine clothes deceive you.’

When the woman in the wheelchair turned the TV off, they heard a lullaby being sung elsewhere in the flat.

‘Ai-ai-ai-ai-ai-BOFF-BOFF.’

Johanne chuckled. ‘That would frighten the life out of my children.’

The other woman steered the wheelchair over to a low coffee table and lifted up a cup. She took a sip, wrinkled her nose and put the cup down again.

‘I guess I should go home,’ Johanne said, though it sounded like a question.

‘Yes,’ the other woman replied. ‘You should.’

‘Thank you for your help. For all your help over the past few months.’

‘There’s not much to thank me for.’

Johanne rubbed her lower back lightly before pushing her uncontrollable hair back behind her ears and straightening her glasses with a slim index finger.

‘Yes, there is,’ she said.

‘I think you just have to learn to live with it. There’s nothing you can do about the fact that she exists.’

‘She threatened my children. She’s dangerous. Talking to you, being taken seriously, being believed . . . it’s at least made things easier.’

‘It’s nearly a year ago now,’ the woman in the wheelchair continued. ‘It was last year that things were really serious. What happened this winter . . . well, I can’t help thinking that she’s . . . teasing you.’

‘Teasing me?’

‘She triggers your curiosity. You are a seeking person, Johanne. That’s why you do research. Your curiosity is what gets you involved in investigations that you actually want nothing to do with, and that’s what is driving you to get to the bottom of what it is this woman wants from you. It was your curiosity that . . . that brought you here. And it is—’

‘I have to go,’ Johanne interrupted, with a fleeting smile. ‘No point in going through it all again. But thank you all the same. I can see myself out.’

She stayed standing where she was for a moment. She was struck by how beautiful the paralysed woman was. She was slim, almost too thin, with an oval face and eyes that were remarkably like the little girl’s: ice blue, clear, and nearly leached of colour, with a broad black ring round the iris. Her mouth was shapely, with a clearly defined upper lip, surrounded by delicate, beautiful wrinkles that indicated that she must be well over forty. She was elegantly dressed in a light blue V-necked cashmere sweater and jeans that were presumably not bought in Norway. A simple, big diamond hung, swinging gently, in the hollow of her neck.

‘You look lovely, by the way!’

The woman smiled faintly, almost embarrassed.

‘See you again soon,’ she said and rolled over to the window, where she remained sitting with her back to her guest, without saying goodbye.

IV

The snow lay knee-deep over the long strips of field. It had been frosty for a long time now. The naked trees in the woods to the west were glazed with ice. Every now and then his snowshoes broke through the rough crust on the snow, making him nearly lose his balance for a moment. Al Muffet stopped and caught his breath. The sun was about to go down behind the hills to the west. Only the odd bird cry broke the silence. The snow glittered in the golden-red evening light and the man with the snowshoes stood for a moment to watch a hare that leapt out from the woods and zigzagged down to the stream on the other side of the field.

Al Muffet breathed in as deeply as he could.

He had never doubted that he had done the right thing. When his wife died and he was left with three daughters aged eight, eleven and sixteen, it took only a matter of weeks for him to realise that his career at one of Chicago’s prestigious universities was simply not compatible with sole responsibility for his children. Their finances also implied that he should move what was left of his family to a quiet place in the country as soon as possible.

Three weeks and two days after the family had moved to their new home at Rural Route #4 in Farmington, Maine, two passenger planes each flew into a tower on Manhattan. A few minutes later, another thundered into the Pentagon. That same evening, Al Muffet closed his eyes in silent gratitude for his foresight: already, as a student, he had shed his real name, Ali Shaeed Muffasa. The children were sensibly called Sheryl, Catherine and Louise, and had all inherited their mother’s delightful snub nose and ash-blonde hair.

Now, a good three years later, barely a day passed without him enjoying his country life. The girls were blossoming, and he had rediscovered the joys of clinical practice remarkably quickly. His practice was varied, a good mixture of small animals, pets and farm animals: poorly canaries, dogs giving birth, and every now and then an aggressive ox that needed a bullet through the head. Every Thursday he played chess down at the club. He went to the cinema with the girls on Saturdays. On Monday evenings he generally played a couple of games of squash with a neighbour who had a court in a converted barn. One day followed the next, a steady flow of pleasing monotony.

Only on Sundays were the Muffets any different from the rest of the community. They did not go to church. Al Muffet had lost any contact with Allah a long time ago, but had no plans of getting to know God. Initially, there was some reaction: veiled questions at parents’ meetings, ambiguous remarks at the petrol station or by the popcorn machine at the cinema on a Saturday night.

But these gradually petered out.

Everything passes, Al Muffet thought to himself as he struggled to unearth his watch, which was buried under his mitten and his down jacket. He had to get a move on. His youngest daughter was going to make dinner, and from experience, he knew that it was worthwhile being at home when she did. Unless he wanted to be greeted by an extravagant meal and a bare goodies store. The last time Louise had made dinner it had been a Monday night and she had served up a four-course meal of foie gras, truffle risotto, and the venison he had got in the autumn and intended to have for their annual Christmas dinner with the neighbours.

The cold had more bite now that the sun had gone down. He took off his mittens and put his palms to his cheeks. A few seconds later he started to walk, with the long, slow snowshoe steps that he had finally mastered.

He had not watched the swearing-in of the President, but not because it would bother him in any way. When Helen Lardahl Bentley had entered the public arena, big time, ten years ago, he had in fact been horrified. He remembered with unnerving clarity that morning in Chicago, when he was lying at home in bed with flu, channel-hopping through his fever. Helen Lardahl, so different from how he remembered her, making a speech in the Senate. Gone were the glasses. The puppy fat that had stayed with her far into her twenties had fallen away. Only characteristics such as the determined diagonal movement through the air with an open, flat hand to underline every second point convinced him that it really was the same woman.

How does she dare? he’d thought at the time.

And then he had gradually come to accept it.

Al Muffet stopped again and drew the ice-cold air into his lungs. He was down by the stream now, where the water was still running under a lid of clear ice.

She trusted him, it was simple. She must have chosen to trust the promise he had made back then, a lifetime ago, in another life and in a completely different place. Given her position, it would have been simple to find out whether he was still alive, still lived in the US.

But now she had got herself elected as the world’s most powerful national leader, in a country where morality was a virtue and double standards a necessity.

He stepped across the stream and scrambled over the mounds of snow left by the snowplough. Suddenly his pulse was so fast that his ears were ringing. It was so long ago, he thought, and took off his snowshoes. With one in each hand, he started to run down the small, wintry road.

‘We got away with it,’ he whispered in rhythm with his own heavy steps. ‘I am to be trusted. I am a man of honour. We got away with it.’

He was far too late. No doubt he would get home to oysters and an open bottle of champagne. Louise would say it was a celebration, in honour of the first female president of America.

MONDAY 16 MAY 2005

I

‘Bloody great timing. Who the hell chose that date?’

The Director General of the Norwegian Police Security Service, PST, brushed a hand over his cropped ginger hair. ‘You know perfectly well,’ replied a slightly younger woman, who was watching an old TV screen that was balanced on a filing cabinet in the corner of the office. The colours were faded and a black stripe flickered at the bottom of the image. ‘It was the Prime Minister. Great opportunity, you know, to show the old country in all its national romantic glory.’

‘Drunkenness, trouble and rubbish everywhere,’ grunted Peter Salhus. ‘Not very romantic. Our national day has become pure hell. And how in God’s name’ – he was shouting now as he pointed at the TV – ‘do they think it will be possible to look after that woman?’

Madam President was about to set foot on Norwegian soil. In front of her were three men in dark overcoats. The characteristic earpieces were clearly visible. Despite the low cloud, they were all wearing sunglasses, as if they were trying to parody themselves. Their doubles were coming down the steps from Air Force One behind the President; just as big, just as brooding and just as devoid of expression.

‘Looks like they could do the job on their own,’ Anna Birke-land quipped, nodding at the screen. ‘And I hope that no one else shares your . . . pessimism, shall we say. I’m actually quite worried. You don’t normally . . .’

She broke off. Peter Salhus didn’t say anything either, his eyes fixed on the TV screen. It was not like him to have such an outburst. Quite the contrary: when, a couple of years previously, he was appointed as director general, a post that historically had some embarrassing blemishes, it was because of his placid and pleasant nature, and not because of his military background. The protests from the left had been muted by the revelation that Salhus had been a young socialist. He had joined the army at nineteen in order to ‘expose American imperialism’, he explained with a smile in an interview broadcast on TV. When he then gave an earnest one-anda-half-minute account of the threats facing modern society, which most people could recognise, the battle was as good as won. Peter Salhus had changed out of his uniform and into a suit, and moved into the PST offices, if not with universal acclaim, then at least with cross-party support behind him. He was well liked by his staff and respected by his colleagues abroad. His cropped military hair and salt-and-pepper beard gave him an air of old-fashioned, masculine confidence. Paradoxically, he was in fact a popular head of security.

And Anna Birkeland had never seen this side of him.

The light in the ceiling was reflected in the sweat on his brow. He rocked his body backwards and forwards, apparently without realising. When Anna Birkeland looked at his hands, they were clenched tight.

‘What is it?’ she asked in such a quiet voice that it almost seemed she didn’t want an answer.

‘This was not a good idea.’

‘Why haven’t you stopped it, then? If you’re as worried as you seem to be, you should have—’

‘I’ve tried. And you know it.’

Anna Birkeland got up and walked over to the window. Spring was not springing in the pale grey afternoon light. She put her palm up to the glass. An outline of condensation flared up briefly, then disappeared.

‘You had your objections, Peter. You outlined possible scenarios and pointed out possible problems. But that’s not the same as trying to stop something.’

‘We live in a democracy,’ he said. As far as Anna could make out, there was no irony in his voice. ‘It is the politicians who decide. In situations like this, I’m merely an adviser. If I could decide—’

‘Then we would keep everyone out?’ She turned suddenly. ‘Everyone,’ she repeated, louder this time. ‘Everyone who might in any way threaten this idyllic village called Norway.’

‘Yes,’ he replied. ‘Perhaps.’

His smile was difficult to interpret. On the TV screen, the President was being led from the enormous jet towards a temporary lectern. A man dressed in a dark suit fiddled with the microphone.

‘Everything went well when Bill Clinton came,’ Anna said and carefully bit her nail. ‘He went walkabout in town, drank beer, and greeted every man and his dog. Even went for cake. Without it being planned and agreed in advance.’

‘Yes, but that was before.’

‘Before what?’

‘Before nine/eleven.’

Anna sat down again. She ran her hands up her neck and lifted her shoulder-length hair. Then she looked down and took a breath as if about to say something, but instead released an audible sigh. The President had already finished her short speech on the silent TV.

‘Oslo Police is responsible for the bodyguards now,’ she said finally. ‘So, strictly speaking, the President’s visit is not your concern. Ours, I mean. And in any case . . .’ she waved a hand at the filing cabinet under the TV, ‘we’ve found nothing. No movement, no activity. Not among any of the groups we’re aware of here. Not even on the peripheries. We’ve received nothing from elsewhere to indicate that this will be anything other than a friendly visit from . . .’ her voice took on the intonation of a newsreader, ‘a president who wishes to honour her homeland and the USA’s great ally, Norway. There is nothing to indicate that anyone has other plans.’

‘Which is strange, isn’t it? This is . . .’

He held back. Madam President got into a dark limousine. A woman with lightning hands helped her with her coat. It was hanging out of the car and about to be caught by the door. The Norwegian prime minister smiled and waved at the cameras, a bit too vigorously, with childish delight at having such an important visitor.

‘There goes the world’s most hated person,’ Peter finished and nodded at the screen. ‘I know that plots are hatched to assassinate the woman every day. Every bloody day. In the States, in Europe. In the Middle East. Everywhere.’

Anna Birkeland sniffed, and wiped the tip of her nose with her finger.

‘But that’s always been the case, Peter. And she’s not the only one that people want to assassinate. All over the world intelligence services are constantly uncovering irregularities so that they don’t become realities. And America has got the world’s best intelligence service, so—’

‘People in the know might dispute that,’ he interrupted.

‘And the world’s most efficient police organisation,’ she continued, unaffected. ‘I don’t think you need lose any sleep worrying about the President of the United States of America.’

Peter Salhus got up and pressed the off button with his great index finger, just as the camera zoomed in for a close-up of the small American flag attached to the side of the bonnet. It was whipped into a frenzy of red, white and blue as the car accelerated.

The screen went black.

‘It’s not her I’m worried about,’ Peter Salhus said. ‘Not really.’

‘Now I really don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Anna exclaimed, with obvious impatience. ‘I’m off. You know where to find me if you need me.’

She picked up a voluminous folder from the floor, straightened her back and walked to the door. She had half opened it when she turned and asked, ‘If it’s not Bentley you’re worried about, who is it?’

‘Us,’ he replied, sharp and concise. ‘I’m worried about what might happen to us.’

The door handle felt strangely cold against her palm. She took her hand away. The door slowly closed again.

‘Not the two of us.’ He smiled at the window; he knew she was blushing, and didn’t want to look. ‘I’m worried about . . .’ He drew a big, vague circle of nothing with his hands. ‘Norway,’ he finished, and finally looked her in the eye. ‘What the hell will happen to Norway if something goes wrong?’

She wasn’t sure that she understood what he meant.

II

Madam President was finally alone. She had a headache clinging to the bottom of her skull, as she always did at the end of a day like today. She sat down carefully in one of the cream armchairs. The headache was an old friend, a frequent visitor. Medicine didn’t help, probably because she had never disclosed this problem to a doctor and therefore had never used anything other than over-the-counter painkillers. Her headache came at night, when everything was done and she could finally kick off her shoes and put her feet up. Read a book, or maybe close her eyes and think about nothing before falling asleep. But she couldn’t. She had to sit still, leaning back, with her arms out from her body and her feet firmly on the ground. Her eyes half closed, never fully; the red darkness behind closed eyes just made the pain worse. She needed a bit of light. A sliver of light between her lashes. Loose arms with open hands. Relaxed torso. She had to shift her attention as far away from her head as possible, to her feet, which she pressed as hard as she could into the carpet. Again and again, to the beat of her pulse. Don’t think. Don’t close your eyes. Press your feet down. And again, and again.

Eventually, in a delicate balance between sleep, pain and wakefulness, the claws at the back of her head slowly loosened their grip. She never knew how long an attack would last. Generally it was about a quarter of an hour, though sometimes she stared in horror at her watch and could not believe that that was the time. Occasionally, it was only a matter of seconds.

As was the case this time, she realised when she looked at the alarm clock.

She tentatively lifted her right hand and wrapped it round her neck. She continued to sit absolutely still. Her feet were still pulsing against the floor, heel to toe and back again. The cool of her palm made the skin contract across her shoulders. The pain had really vanished, completely. She let out a sigh of relief and got up as slowly as she had sat down.

The worst thing about the attacks was perhaps not so much the pain as the fact that she felt so awake afterwards. Over the past twenty years or so, Helen Bentley had learnt to accept that sleep was something she sometimes just had to do without. She could go for months on end with no pain, but the armchair scenario had almost become a midnight ritual for her over the past year. And as she was a woman who never let anything go to waste, not even time, she constantly surprised her colleagues by how well prepared she was for early-morning meetings.

The US had, unwittingly, elected a president who normally had to make do with only four hours’ sleep. And if it was up to her, her insomnia would remain a secret that she shared only with her husband, who had learnt after many years to sleep with the light on.

But now she was alone.

Neither Christopher nor her daughter, Billie, was with her on this trip. Madam President had gone to great pains to stop them. She still cringed when she remembered the astonished disappointment in her husband’s eyes when she made the decision to travel alone. The trip to Norway was the President’s first official visit abroad after having been sworn in, and it was of a purely representative nature. Not only that, it also was to a country that her twenty-one-year-old daughter would have had great pleasure and interest in visiting. There were a thousand and one good reasons why the family should go, as originally planned.

But she had made them stay at home, all the same.

Helen Bentley took a few cautious steps, as if she was afraid that the floor wouldn’t hold. Her headache had definitely disappeared. She rubbed her forehead with her thumb and index finger as she looked around the room. It was the first time she had really noticed how beautifully the suite was designed. It was done out in cool Scandinavian style, with blond wood, light materials and perhaps a little too much glass and steel. The lights in particular caught her attention. The lamp bowls were made of sand-blasted glass. Though they were not all the same shape, they harmonised with each other in a way that meant that they somehow belonged together without her understanding why. She ran her hand over one of them. A delicate warmth seeped through from the low-wattage bulb.

They’re everywhere, she thought to herself and stroked her fingers over the glass. They’re everywhere, and they’ll look after me.

She could not get used to it. No matter where she was, whatever the occasion, whoever she was with, with no consideration for time or discretion, they were always there. Of course she understood that it had to be like that. But equally, she had realised after barely a month in office that she would never actually get used to the more-or-less invisible bodyguards. The bodyguards who were around her during the day were one thing. She quickly learnt to accept them as part of daily life. She could distinguish them from one another. They had faces. Some of them even had names, names that she was allowed to use, even though she realised that they were likely to be false.

The other ones were worse. The countless invisible ones; the armed, concealed shadows that constantly surrounded her without her ever really knowing where they were. It made her feel uncomfortable; a misplaced sense of paranoia. They were watching over her. They wished her well, to the extent that they actually felt anything more than a sense of duty. She thought she had prepared herself for life as a target, until some weeks before she was sworn in as president, she realised it was impossible to prepare yourself for a life like this.

Not completely, anyway.

Throughout her political career, she had focused on opportunities and power, and judiciously manoeuvred herself in that direction. She had of course met with opposition en route, professional and political, but also a fair dose of ill will and agitation, envy and malevolence. She had chosen a political career in a country with a long history of personified hatred, organised slander, unprecedented misuse of power, and even assassination. On 22 November 1963, as a horrified thirteen-year-old, she had seen her father cry for the first time, and for some days afterwards had believed that the end of the world was nigh. She was still a teenager when Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King were killed in the same tempestuous decade. But she had never actually thought of the assassinations as personal. For the young Helen Lardahl, political assassination was an abominable attack on ideals, on the very values and attitudes that she greedily lapped up. Nearly forty years on, she still got shivers down her spine whenever she heard the start of the ‘I have a dream’ speech.

When two hijacked planes ripped through the World Trade Center in September 2001, she therefore interpreted it in the same way, as did nearly three hundred million of her compatriots – it was an attack against the American ideal. The close to three thousand victims, the unbelievable material damage, the permanent change to the Manhattan skyline all merged into a greater whole: the American dream.

Thus every victim, every courageous firefighter, every fatherless child and every broken family became a symbol of something far greater than themselves. And this made it easier for the nation and those left behind to bear the loss.

That was how she had experienced it. That was how she had felt.

Only now, now that she had taken on the role of Target No. 1, had she started to understand the underlying deceit. Now it was she who was the symbol. The problem was that she didn’t feel that she was a symbol; she was more than that. She was a mother. She was a wife and a daughter, a friend and a sister. For nearly two decades she had worked solely towards achieving this goal of becoming the President of the United States. She wanted power, she wanted possibility. And she had succeeded.

At the same time, the deceit had become increasingly clear to her.

And it could be very bothersome on sleepless nights.

She remembered one of the funerals she had gone to, in the way that they had all attended funerals and memorial services – senators and congressmen, governors and other prominent figures, all wanting to be seen to be sharing the Great American Grief, in full view of photographers and journalists. The deceased was a woman who had recently been employed as a secretary in a company that had its offices on the seventy-third floor of the North Tower.

Her husband could not have been much more than thirty. He sat there, on the front bench in the chapel, with a toddler on each knee. A little girl of about six or seven sat beside him, stroking her father’s hand over and over, almost manically, as if she already understood that he was about to lose his mind and needed to be reminded of her existence. The photographers concentrated on the children: the twins, aged one or two, and the lovely little girl, dressed in black, a colour that no child should have to wear. Helen Bentley, on the other hand, stared at the father as she passed the coffin. What she saw in his face was not grief, or certainly not grief as she knew it. His features were distorted by despair and anger, pure simple fear. This man could not understand how life would go on. He had no idea how he was going to manage to look after the children. He didn’t know how he was going to make ends meet, to have enough money to pay the rent and school fees, to have the energy to raise three children on his own. He had achieved his fifteen minutes of fame because his wife had been in the wrong place at the wrong time and was now absurdly exalted as an American hero.

We used them, Helen Bentley thought to herself, and stared out of the panorama windows that faced south over the dark Oslo Fjord. There was still a strange, pale blue light in the sky, as if it wasn’t quite ready to accept the night. We used them as symbols to make people toe the line. And we succeeded. But what is he doing now? What happened to him? And the kids? Why have I never dared to find out?

Her guardians were out there. In the corridors. In the rooms around her. On the roof and in parked cars; they were everywhere, looking after her.

She had to get some sleep. The bed looked inviting, with a big, down-filled duvet, like the one she’d had as a child in her grandmother’s attic in Minnesota; when she was blissfully ignorant and could close the world out simply by pulling a checked duvet over her head.

This time ‘the people’ would not close ranks. That was why it was worse and so much more threatening.

The last thing she did before falling asleep was to set the alarm on her mobile phone. It was half past two, and bizarrely, it was already starting to get light again outside.

TUESDAY 17 MAY 2005

I

As always, the Norwegian national day had started before the devil got his shoes on. Oslo Police had already arrested more than twenty teenagers out celebrating their final year in school, for being drunk and disorderly. They were now sleeping it off while they waited for their fathers to come and bail them out with indulgent smiles. The rest of the school-leavers, or ‘Russ’ as they were popularly called, were doing their best to ensure that nobody slept in or was late for the national-day parade. Cheap buses that had been converted and fitted with sound systems that cost the earth boomed through the streets. Here and there, a small child was already dressed up and out, and they ran like puppy dogs after the painted Russ buses and begged for the traditional Russ cards from the school-leavers. Groups of war veterans gathered in graveyards – fewer and fewer for each year that passed – to celebrate peace and freedom. Brass bands trudged through the town to a half-hearted march. Offkey trumpet notes ensured that anyone who might still against all odds be asleep could now just as well get up and have the first coffee of the day. In the city’s parks, confused junkies emerged from under their blankets and plastic bags, unable to grasp what was happening. The weather was the same as normal, with clouds breaking up to the south, but no sign that the temperature would rise. On the contrary, there was every reason to expect a shower or two, judging by the grey skies to the north. Most of the trees were still half naked, though the birch trees were now sporting buds and pollen-saturated catkins. All over the country, parents forced woollen underwear on their children, who had already started to pester them for ice cream and hot dogs, long before breakfast. Flags fluttered and flag ropes rattled on a brisk breeze.

The kingdom of Norway was ready to celebrate.

A policewoman stood shivering outside a hotel in the centre of Oslo. She had been standing there all night. As discreetly as possible, she looked at her watch at steadily shorter intervals. Someone would be coming to replace her soon so she could knock off. She had managed to snatch the occasional conversation with a colleague who was posted about fifty or sixty metres away, but apart from that, the night had been interminable. For a while she had tried to pass the time by guessing who was a bodyguard. But then, at around two in the morning, the steady stream of people coming and going had stopped. As far as she could see, there was no security on the roofs. No dark, easily identifiable cars with secret agents had cruised by since the American president had been dropped off and escorted into the hotel around midnight. They were, of course, still there. She knew that, even if she was only a constable who had been sent to decorate the outside of the hotel in a newly cleaned uniform – and to get cystitis.

A cortège of cars was approaching the main entrance of the hotel. The street was normally open to all traffic, but now it was closed, with loose metal barriers creating a temporary square outside the modest entrance.

The constable opened up two of the barriers, as she had been instructed to do in advance. Then she retreated to the pavement. She edged her way towards the entrance. Maybe she could catch a glimpse of the President up close, on her way to the national-day breakfast. That would be a welcome reward for a hellish night. Not that she was usually bothered about that sort of thing, but the woman was the most powerful person in the world, after all.

No one stopped her.

Just as the first car pulled up, a man came sprinting out of the hotel door. He had a bare head and was not wearing an overcoat. He had a walkie-talkie in a holster over his shoulder, and the constable could see the top of the butt of a gun just inside his open jacket. His face was remarkably devoid of expression.

A man in a dark suit got out of the passenger seat of the first car. He was small and compact. Before he was fully out of the car, the man with the walkie-talkie, who had come to meet him, grabbed hold of his arm. They stood like this for a few seconds, the larger man with his hand on the smaller man’s arm, as they had a whispered conversation.

The small Norwegian did not have the same poker face as the American. His mouth fell open for a few seconds, before he pulled himself together and straightened up. The policewoman took a couple of tentative steps closer to the car. She still couldn’t make out what they were saying.

Four other men had come out of the hotel. One of them was having a muted conversation on a mobile phone while he stared blankly at a ghastly polished steel sculpture of a man standing waiting for a taxi. The three other agents were gesturing to someone the policewoman couldn’t see, and then, as if on command, they all looked in her direction.

‘Hey, you! Officer! You!’

The policewoman gave an uncertain smile. Then she lifted her hand and pointed to herself with a questioning expression.

‘Yes, you,’ one of the men repeated, and bounded over to her. ‘ID, please.’

She produced her police ID from her inside pocket. The man looked at the Norwegian coat of arms. Without even turning the card to check the photograph, he handed it back.

‘The main door,’ he hissed, as he turned to run back. ‘No one in, no one out. Got it?’

‘Yes, yes.’ The policewoman swallowed, wide-eyed. ‘Yes, sir!’

But the man was already too far away to hear that she had eventually remembered how to say it politely. Her colleague who been on the same night shift was also heading towards the main entrance. He had obviously been given the same instructions as she had, and seemed uncertain. All four cars in the cortège suddenly accelerated, spun out of the square and disappeared.

‘What’s going on?’ whispered the constable, positioning herself in front of the double glass doors. Her colleague looked utterly confused. ‘What the hell is going on?’

‘We’ve just got to . . . We’ve just got to watch this door, I think.’

‘Yeah, I realised that. But . . . why? What’s happened?’

An elderly lady tried to get the doors to open from inside. She was wearing a dark red coat and a funny blue hat, with white flowers around the rim. Pinned to her chest she had a 17th of May ribbon that was so long it almost touched the ground. She eventually managed to fight her way out.

‘Excuse me, ma’am. I’m afraid you’ll have to wait a while.’ The policewoman gave her friendliest smile.

‘Wait?’ the woman exclaimed in a hostile voice. ‘I have to meet my daughter and granddaughter in quarter of an hour! I’ve got a place at—’

‘I’m sure it won’t be long,’ the policewoman assured her. ‘If you could just . . .’

‘Can I be of help?’ asked a man in a hotel uniform, as he strode quickly over from the reception desk. ‘Madam, if you’d like to come this way . . .’

‘Oh, say! can you seeee, by the dawn’s early liiight . . .’

A deep voice suddenly resounded through the morning air. The policewoman spun round. A large man in a dark coat carrying a microphone was approaching from the north-west, where the blocked road led to a parking place on the south side of the main railway station. He was followed by a brass band.

‘What so prouuudly we hailed . . .’

She recognised him immediately, and the musicians’ white uniforms were unmistakable as well. She suddenly remembered that, according to plan, the Sinsen Youth Brass Band and the man with the powerful voice were going to help make the President feel at home at seven thirty sharp, before she was taken to the palace for breakfast.

A roll of drums grew into a roll of thunder. The singer took a deep breath and gathered his strength for a new burst: ‘At the twilight’s last gleeeaming . . .’

The brass band was trying to play something that resembled a march, whereas the singer obviously preferred a more theatrical style. He was always a note or two behind, and his exaggerated movements were somewhat in contrast with the musicians’ military posture.