Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

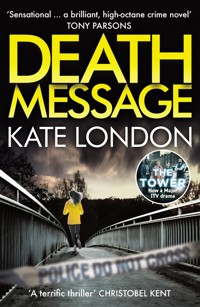

BOOK 2 OF THE TOWER - NOW A MAJOR ITV DRAMA 'Sensational... A brilliant, high-octane crime novel' Tony Parsons October 1987: the morning after the Great Storm. Fifteen-year-old Tania Mills walks out her front door and disappears. Twenty-seven years later her mother still prays for her return. DS Sarah Collins in the Met's Homicide Command is determined to find out what happened, but is soon pulled into a shocking new case and must once again work with a troubled young police officer from her past, Lizzie Griffiths. PC Lizzie Griffiths, now a trainee detective, is working in the Domestic Violence Unit, known by cops as the 'murder prevention squad'. Called to an incident of domestic violence, she encounters a vicious, volatile man - and a woman too frightened to ask for help. Soon Lizzie finds herself drawn into the centre of the investigation as she fights to protect a mother and daughter in peril. As both cases unfold, Sarah and Lizzie must survive the dangerous territory where love and violence meet.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 584

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my sisters, Ann and Felicity

Through the sharp hawthorn blows the cold wind.

Shakespeare, King Lear

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

October 1987

Part One

Chapter 1 Wednesday 9 July 2014

Chapter 2

Chapter 3 Thursday 10 July 2014

Chapter 4

Chapter 5 Friday 11 July 2014

Chapter 6

Part Two

Chapter 7 Wednesday 16 July 2014

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13 Thursday 17 July 2014

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20 Friday 18 July 2014

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28 Saturday 19 July 2014

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34 Sunday 20 August 2014

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Part Three

Chapter 37 Thursday 24 July 2014

Chapter 38 Friday 25 July 2014

Chapter 39

Chapter 40 Saturday 26 July 2014

Chapter 41 Sunday 27 July 2014

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Epilogue

Chapter 48 Friday 1 August 2014

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

About the Author

Also by Kate London

Acknowledgements

Copyright

PROLOGUE

October 1987

The great storm of 1987 was the before and after of Claire Mills’ life. More than twenty years later, she still woke in the middle of the night with a sudden ice-cold alarm that had her sitting up and seeing with luminous clarity those uprooted trees and crushed vehicles. The terror in her heart in the lonely hours of the morning was always the same: that the smaller traces of disaster in her life that she had chosen to ignore for so long had, on the morning after the storm, been emphatically written on the landscape, crying out for her to notice them at last. Among the many, many reproaches she made to herself was this one: she had failed to pay attention to portents.

She had known her daughter had secrets.

She had known too that her husband was having an affair, but whenever she had thought of his all-too-obvious infidelity – and she admitted to herself now that she had strived not to think of it – her sideways-glancing decision had always been to ignore it. It would blow over. His affair had perhaps not been the cause of what happened, but it was another symptom of her wilful somnambulism. She had been too attached to her becalmed life. She had kept a tidy house. She had loved her central heating and fitted carpets, the newly installed Everest windows.

When daylight came, it offered the consolations of reason. The storm had, perhaps, facilitated in some way what followed, but it had surely been no supernatural harbinger. Still, each year, whenever the days shortened into autumn, she faced alone her belief that her own wilful blindness had brought such disaster on her.

Those trees, those upturned roots.

In the warm confines of number 14 Eccleshall Drive, the evening of 15 October 1987 had held no surprises, no deviations from the normal. Alone in her sitting room, Claire had watched the late-evening weather forecast. Michael Fish – bald pate, thin-framed glasses – stood confidently in front of his isobars. ‘Earlier on today,’ he said, ‘a woman rang the BBC and said there was a hurricane on the way.’ He gave a little chuckle: it was easier after all in the 1980s to dismiss the fears of women. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said with a smile. ‘No hurricane is on its way.’

So England went to bed. This was a newly minted country. An Iron Lady had put the Great back into Britain. This was not a nation that was frightened of wind.

Claire stirred herself from her seat in front of the television. Her husband, Ben, sat alone in the dining room, his head bent beneath the overhead lamp as he studied for his yachtmaster’s certificate, not considering the ships that would break their moorings in the night. She got up and pushed the button on the television. In the kitchen, she boiled the kettle, filled a hot-water bottle, and then, in her slippered feet, walked steadily up the stairs to her daughter, who was sitting at her desk doing her homework. She lifted back the duvet of her daughter’s single bed and placed the bottle on the mattress.

‘Lights off now, Tania.’

It was in the early hours that Claire became aware of a constant banging, as if horses were galloping on hard floors above her. Still asleep, she couldn’t place it. What was happening? Was it an argument? Was someone throwing chimney pots from the roof? Gradually it drew her towards the surface of consciousness. There was a continuous wailing glissando, as if the atmospheric layers high above the bay window of her bedroom were being played like a saw. The house, she realized, now fully awake, was moving, actually moving, leaning and creaking. She reached out to her husband, said, ‘Ben, Ben,’ but he rolled away from her, groaned, pulled the covers over himself. She swung her feet out of bed and into the pink flip-flop slippers that waited for her beside the bed. She pulled on her dressing gown and went downstairs.

Tania was already there, standing in the front room in silky ivory pyjamas and bare feet. The storm was howling outside, banging and crashing, but she seemed to have found her own little pool of silence. The light switches were empty of power and she was standing in the half-light shed by the window. Claire felt blessed by this suddenly intimate image of her daughter. Usually Tania had that teenage awkwardness that distrusts or is ashamed of its beauty, that hunches over and avoids the gaze of others, but here, thinking herself unobserved, she stood gracefully, with a timeless poise like one of Degas’ dancers. Her hair, tied into several long plaits as preparation for her latest silly hairstyle, fell down her slender back. Her weight was on one hip, the other foot arched, with the toes turned under as if carrying some memory of primary-school ballet classes. Claire had always loved her daughter’s long, thin feet, felt she had known the hard little heels even before Tania was born. They had made corners through her taut pregnant stomach, as if she was concealing little anvils inside her belly.

She joined her daughter at the window and they stood side by side and watched the lime tree in the garden opposite as it bowed constantly like a courtier desperate to please the wind. The noise was incessant, wailing, banging. Lights were on in other houses in the street. Faces stared from other windows.

Tania said quietly, ‘I love it, Mum. I love it.’

‘You’re not frightened?’

Tania, mesmerized by the travails of the tree opposite, did not answer immediately. A flowerpot had fallen from a first-floor window and crashed into the street. A solitary uprooted geranium lay on the pavement. A bin, taking the opportunity to escape its usual drab destiny, rolled down the road.

Tania said, ‘It’s scary, but it’s fab too. Like The Wizard of Oz. I’ve always liked the first bit the best, the black-and-white bit. How the house turns in the twister and the cow blows past the window, and the two men rowing in a boat raise their hats to Dorothy. The Cowardly Lion and the Tin Man are there already in their overalls. And the Wizard himself, with his horse-drawn caravan—’

Claire interrupted, doing her best Professor Marvel. ‘Better get under cover, Sylvester, there’s a storm blowing up, a whopper.’

Tania laughed, and Claire sneaked her arm around her daughter’s narrow waist, hugging her to her. Tania was too old for that usually, but somehow the storm had made an exception.

‘Oh yes. I loved it too. That howling wind and the galloping horses and the trees outside the window, just like now.’

The harsh bell of the phone woke them in the morning from their resumed sleep. Tania was too quick for her mother, hammering down the stairs and scooping up the receiver. Claire rolled onto her back and rubbed her exhausted eyes. Ben had already left without saying goodbye, but the bed still carried his whiskery male smell and the warm indentation of his sleeping form. Ignoring destruction, he had set out to weave through the blocked streets in his new Audi. He was proud of that car. It was brand new. Gold-coloured.

Claire called down to her daughter. ‘What is it?’

Tania’s feet running lightly up the stairs. Suddenly she was in a hurry, but she popped her head round the bedroom door.

‘Oh, just Katherine, Mum. School’s cancelled for today. There’s trees everywhere apparently. We’re going to meet up.’

Katherine: Tania’s best friend. Since primary school they’d been inseparable. When Katherine had started playing the violin, Tania had insisted on learning too. Katherine was from a musical family, but from the start everyone said it was Tania who had real talent. Claire’s heart filled to bursting when she saw the two girls walking down the street together in their school uniforms, their violin cases swinging by their legs. They hadn’t been getting on so well recently – perhaps it was because Tania’s playing seemed to be irrevocably pulling ahead of her friend’s – but still, Claire could tell that this was one of those friendships that would last. She could see them at each other’s weddings.

She made her way downstairs and set to work clearing up her husband’s breakfast things. She needed to get a move on. There’d been no call from Mrs Hitchens, the woman whose child she minded. She must be trying to get in to work too. Claire turned on the radio. From upstairs came a loud pounding and a female voice filled with longing. She recognized the song. ‘River Deep Mountain High.’

She called upstairs. ‘Tania, turn it down, I’m trying to listen to the radio.’

Train lines are closed, and thousands have been left without power . . .

Through the ceiling came the wall of sound that was pure Phil Spector. Fancy Tania getting into that stuff. She was twenty years too late, surely. The music built, cavernous, with a rhythm that wrenched at Claire’s heart and seemed to insist she tap her feet and click her fingers. She switched the radio off and called up again, trying to compete with the music.

‘Tania, do you want porridge or an egg?’

She climbed the stairs. Tania was in her bedroom, swinging her hips from side to side, and doing that punk jumping-about thing that her generation were all doing. Her back was turned. She was admiring her moves in the mirror.

Claire moved in behind her. After a slightly sceptical pause, she began to swing her own hips. She raised her arms and moved her hands from side to side.

‘This is how you do it.’

Tania cringed. ‘Oh Mum.’

‘Don’t be mean. I was young once too.’

The sound was building again, irresistible. A pounding rhythm that she couldn’t seem to ever catch up with. Tina Turner breaking your heart. Claire put her hands above her head, turned them from the wrists in flamboyant 1960s circles, swung her hips. It was a long time since she’d danced, but she used to love it before Tania was born, before she was married.

Tania laughed and joined in, moving in synch with her mother.

The memory is very strong, and nearly twenty-seven years later, Claire Mills conjures it: Tania, wearing her big colourful glass earrings and blue sparkly eyeshadow. The music has stopped leaving them both breathless. Tania has lost the grace of last night and recovered her adolescent awkwardness. Her skirt’s too short. Her hair is out of its plaits and has frizzed out. There’s a smell of hairspray. Her school timetable is pinned to the mirror. Claire will miss her when she goes to university. Not long now. Just three years. At this moment, she is so beautiful that Claire could squeeze her until she could breathe no more. She says, ‘Darling, you look lovely.’

‘Thank you, Mum.’

She doesn’t want to spoil the moment. But still, you have to bring them up properly. It’s part of loving them.

‘Just that skirt . . .’

Tania wrinkles her nose. ‘What?’

Claire kisses her daughter on her head. ‘Well, just maybe a tiny bit short. Up to you.’

From downstairs, the smell of burning.

‘Oh Christ, the toast.’ And Claire runs down the stairs and opens the windows, fanning the smoke outside with a tea towel.

Five minutes later: Tania in the kitchen doorway. Denim jacket, drainpipe jeans, two strings of necklaces, orange lipstick, school bag slung over her shoulder, violin case in her hand.

‘I’m off, Mum.’

‘You haven’t had any breakfast.’

‘It’s OK, I don’t want any.’

Outside the kitchen window, Mrs Hitchens draws up in her new Sierra. Fancy her trying to get in to work on a day like this! If it were Claire, she would have jumped at the opportunity to spend the day with her child. But even though the school has closed, Tania is still going out. She’s going to revise with her best friend, hang out, listen to records.

‘But you’ve got to eat, Tania.’

Sitting alone in her bed, Claire sees it as if it is the present. Mrs Hitchens unloads her toddler and his day bag from the car. Tania passes, kisses Claire on the cheek. ‘It’s OK, I’ll be fine.’

She opens the front door, Claire stands just behind her in the hall. The lilac tree from the garden opposite is lying across the road. It’s a shame. She loved that tree, particularly in June, when the street smelled of blossom. Mrs Hitchens is walking up the path with little Simon’s hand in hers.

‘You going to Katherine’s, Tania? What time will you be home?’

Tania kisses her again.

‘I dunno, about six.’

Then Mrs Hitchens blocks Claire’s view of her daughter as she walks along the path and away down the street.

And alone in her bed, Claire remembers The Wizard of Oz: Professor Marvel in his horse-drawn caravan. He looks into a crystal ball and persuades Dorothy to go home to Aunt Em and Hunk and Hickory and Zeke, and as Dorothy runs away into the storm he says:

‘Poor little kid. I hope she gets home all right.’

PART ONE

1

Wednesday 9 July 2014

Acrow – glistening black and iridescent – was jumping about on the flat roof. A small, slim woman stood beside him, smoking. Detective Sergeant Sarah Collins wore polished black Oxford brogues and a grey trouser suit that in recent months had become slightly too roomy around the waist. Her hair was short, her hands tidy, the nails neatly filed but unpolished. From a distance, the simple neutrality of her appearance might have made her seem younger than her years, but close up, the mark of experience on her face aged her somewhere in her mid-thirties. It was a simple face – square-jawed, even-featured – that didn’t look as though it easily broke into a smile but a seriousness and intelligence in the eyes softened any hint of severity.

Sarah extinguished her cigarette and threw the crow one of the nuts she had brought for him. How silly: tears were suddenly rolling down her face. She couldn’t help but think that it said something truly ridiculous about your life when you were sad about saying goodbye to a crow. She pulled the back of her hand across her face, turned away from the bird and looked towards the river.

A cruiser was moving slowly upstream full of sedentary tourists, the sightseers of the megacity skating upon the river’s surface as shallowly as water boatmen. Sarah knew too much about the Thames. She could no longer see it as a place for pleasure cruises. Nor was it any more to her a river of history and literature. Not Elizabeth I making her way downstream on a gilded barge. Not even Dickens’ river of fog and industry, of docks and cranes, toerags, mudlarks and stevedores eking out a living from its dirty but profitable shores. No, policing had made the Thames an impersonal place, a place of physics. The grey-brown canalized river was an inexorable tidal sweep, a mass of cold and filthy water in relentless laminar flow. She knew how young men set off pissed and high-spirited from one bank only to find themselves suddenly in the grip of a current that was accelerating powerfully, sweeping them downstream as small and irrelevant as Poohsticks. She knew how bodies snagged like refuse on the clean-up cages. Unbidden, it entered her mind that perhaps it was those in despair who knew the river best, who came to it as if on pilgrimage with their weighted rucksacks and cast themselves upon its indifference.

For three years, attached to the Directorate of Specialist Investigations, Sarah had had this view of the Thames from the flat roof outside her office window. Deaths in contact with police had been her bailiwick. At the start of her posting it had seemed clear that her job was to contradict the river, to assert the importance of each little life, however small it might be in the scale of the universe. Recently, though, this conviction had threatened to slip away from her, as though her voice were only snatched up and dissipated by the river’s indifferent roar.

She’d joined the directorate with a certain defiance. After all, investigating the police wasn’t a job every officer wanted. Perhaps that was what had attracted her. It was an arena that demanded pure impartiality, an ideal of investigation at its purest. It had been a badge of honour for her to be fearless, impervious to opinion. It was as if she had believed she could put her hand in the fire time and time again and never be scorched.

Well, she’d been wrong.

It was six months since her former colleague, Detective Constable Steve Bradshaw, had let her know exactly what he thought of her, and it had hurt. She’d admired him as a detective and thought of him as a friend. ‘No wonder you’re so fucking lonely,’ he’d told her at the end of their last investigation together. He’d gone further, rubbed it in, said he felt sorry for her. He’d told her to get herself a fucking dog.

Ever since the close of that investigation into the deaths of Hadley Matthews, a male police officer, and Farah Mehenni, a teenage immigrant girl, who had fallen to their deaths from a tower block Sarah felt she had been treading water, trying not to get swept away, knowing she had to move on.

She cleared her throat and turned back to Sid, the crow, who was waiting for her, his head cocked, his eye bright and beady, his beak as hard as galvanized rubber. Crows were cleverer than dogs, she’d read, adaptable. ‘You be good,’ she said, and clamped her jaw shut against any more tears.

All detectives have moments of burnout, she told herself. It’s just the nature of the job.

That morning, she’d picked up an unmarked car from her new team in Hendon. She was making a positive move. She was going on promotion to be a detective inspector on Homicide. She knew the unofficial calls would have gone out as soon as her application was in, checking up on her, finding a way to stymie her move if the words spoken into the phone were sufficiently bad. But clearly the words had been good. The boss had said they were happy with her, and he must have meant it.

She hung up the bag of bird food and ducked under the open window into her office, determined to put her stuff into the car quickly and leave without a backward glance. But Jez, one of her detective constables, was waiting awkwardly for her, shifting his weight from foot to foot, making her think of that stupid crow. There was that bloody painful boiled egg in her throat again, the heat behind the eyes. They must have that red, swollen look. It must be obvious.

She was saved by a flash of humour. How could she not smile at Jez’s flash gold cufflinks, the high-collared white shirt stretched tightly over his no doubt gym-primed chest, the rather nice leather satchel that had probably cost too much. He was young, good-looking. He tried too hard. He’d been supportive, kind to her when she was at her most lonely. She’d come to like him.

She said, ‘I’d better get a move on.’

There was a pause.

‘I got you something.’ Blushing, he pulled a flat package out of the bag. He might have guessed how suddenly close to tears she was because he added, ‘Don’t worry, Sarah. Open it later.’

She nodded. All her stuff was packed away into the blue plastic crate that stood on her desk.

He said, ‘Can I carry that down to the car for you?’

She shook her head. She wouldn’t risk speaking.

He said, ‘I’ll look after Sid.’

She reached out for a piece of paper, took her pen from her inside jacket pocket and wrote, Thanks, Jez.

He put his hand on hers. ‘No worries. I’ll catch you later. They’re lucky to have you. Homicide will be a bit of a break after this, more straightforward.’

Sarah barely noticed the roads she was driving except when they were suddenly peopled by memories from her years of policing. Fulham Palace Road, outside the florist: a posh guy, face-down stone drunk in the street. She’d been at the very beginning of her service, still in uniform. When they’d got him upright, he’d swayed towards her, breathing fumes of vomit, and told her she looked adorable in that hat. She switched lanes, pulled round the Broadway. Hammersmith nick on her left, two police horses waiting for the gates, their tails switching. She had remembered the Shepherd’s Bush Road as launderettes and tatty takeaways, but it was being repainted in a tasteful muted palette that seemed aimed at suggesting country houses rather than Zone 2 Central London. If you had to be rich even to live on a main road, where on earth were the poor going to go? Shepherd’s Bush itself, reassuringly unsalvageable – a brief memory of rowdy Australians outside the Walkabout – then, on the island of scrubby green encircled by choked traffic, the echo of a crying girl with broken fingernails and a bruise to her cheek.

Back on autopilot as she headed north-east, her thoughts returned to their usual obsession: the investigation into the deaths of PC Hadley Matthews and Farah Mehenni.

It had been her last full investigation at the DSI: the one that had made her look around for a new posting. She and Steve Bradshaw had been practically first on scene and found them both smashed against the concrete but still warm from the life that had left them.

Outwardly the investigation had been a success. Inwardly it was anything but. She felt she’d carry it with her all her career. She thought of the pretty young police constable, Lizzie Griffiths, who’d been on the roof when Hadley and Farah fell and who had run away, going missing for days before she and Steve could locate and interview her. She remembered with more discomfort Lizzie’s boss, Inspector Kieran Shaw. If anyone had to pay it should have been him. She couldn’t pinpoint the feeling that slid uncomfortably inside her: dissatisfaction, frustration, anger – yes, anger certainly. Guilt, maybe. Self-doubt. Certainly a darkness. She checked herself. She needed to stop herself circling around these thoughts, stuck in the same place she’d been for months.

She focused back on the road, the here and now. It was just the nature of a detective’s job: some things stayed with you. Some things couldn’t be resolved. You had to accept that. She was doing that. She was moving on.

She was threading her way through residential streets of 1930s semis, Victorian terraces, slowing for speed bumps and winding through the maze of closures that tried to prevent drivers using them as rat runs. Her years as a detective had made her as knowledgeable about cut-throughs as a London black-cab driver. Here, by an arcade of shops, her first homicide as a detective constable. The victim had made it across the street to bleed out in front of his mother as she ran downstairs from her flat above the off-licence. The murderer had been only seventeen, imagining he was in a movie when he killed the other boy over a bag of weed.

Like a homing pigeon she accelerated along the A41 and then turned left down past the big-money residential developments that were forcing their way upwards like big-money Redwoods. She swung into the entrance to the Peel Centre, passed the security check – the civilians at the gate as usual never in any particular hurry – and pulled round under the concrete portico that framed the entrance to the site.

For a moment she stood on the parade ground, allowing the site to seep into her bones, all her love and hatred for the place, acclimatizing herself to the open space, onto which a light drizzle was falling from a grey sky. Ranged around were low-rise buildings, with white concrete and green fascia, brick-clad columns, strip windows and a skyline of long flat roofs.

Hendon: less famous than New Scotland Yard, but to many who worked for it the secret heart of the Met. The business of dealing with the public, with victims, witnesses, families, suspects: that was all done elsewhere. Hendon was a back office, a place where you wouldn’t be bothered by someone who didn’t know how things worked in the police world of abandoned children, violence and madness. Until recently everyone had trained here and passed out on this parade ground in ranks of shiny shoes, polished buttons and white gloves and it was a place you returned to throughout your service, a place where things were going on but that kept itself to itself. It was going to be a fresh start in an old location.

Carrying her blue plastic crate up the floating treads of the murder block, Sarah snuck into her new office and pulled the door shut.

Her new boss, DCI James Fedden, had told her she would be taking on a job straight away, and sure enough, three storage boxes were waiting on the desk. Operation Egremont: the disappearance of Tania Mills, a teenage girl, back in 1987.

She put her crate on the floor and ran her fingers over the top of the first box. She wanted to open it and start reading, but she should wait until she could work systematically.

Quickly she began setting up her base camp, sorting her stuff into drawers – bags of nuts for those nights when everything was shut and you weren’t getting home, a box of cereal for early warrants, a toothbrush, toothpaste, soap and a towel. She threw her shoulder harness with cuffs and asp into a bottom drawer, got out her legal Blackstones and lined them up on the shelves, set up her coffee machine on the windowsill. Then, with no ceremony, she opened the present from Jez. It was a framed picture of Sid, bearing the handwritten legend Illegitimi non carborundum. It was a nice thought. She hung it on the wall, next to a picture of her dog. They made her smile. Other people had children. She had a dog and a crow.

There was a light knock and then the door was pushed open. Detective Inspector Peter Stokes’ face was hidden by the two large storage boxes he had in his arms.

‘Where do you want them?’ he said.

Sarah cleared a path. ‘Oh, just stick them on the floor.’

He placed them by the window, stood up, scratched the back of his head, looked out towards the parade ground. He’d done his thirty years. This was his final shift and she was his replacement. It was his office she was moving into. He turned, offered his hand.

‘Welcome to Homicide, Sarah. Thanks for taking on Egremont.’

‘Yes, thanks. No problem.’

He was a career detective, grey around the temples, no longer excited about anything. Tall, a bit sweaty and overweight in a baggy suit and an undistinguished tie. Sarah didn’t know him well, but she assumed he could never have been much interested in rank: just got hooked on solving crimes. He seemed reluctant to leave, and that wasn’t really surprising. It couldn’t be easy handing back your warrant card and trying to retrieve as a much older person what it had been like to be a civilian.

The boxes he had brought in were of dark mottled cardboard: better quality than the stuff issued nowadays. The spines, facing towards her, carried printed Op Egremont labels that were peeling away.

She put her hands on her hips. ‘I’m just about to get to grips with it, actually. Is there anything you need to tell me about it?’

He shook his head and mirrored her body language. It was as if they were pulling up their shirt sleeves to start work together.

‘Nothing that springs to mind. Ring me when you’ve read through it. If you’ve got any questions, that is.’

Sarah smiled sympathetically, and after a pause, he smiled too. ‘You don’t have to ring me, of course,’ he said.

‘No, it’s useful to know you wouldn’t mind. Thank you.’

‘The boss sends his apologies, by the way.’

‘That’s fine. He emailed. Thailand, isn’t it?’

‘That’s right. Daughter’s getting married.’ Stokes went over to the desk, put his hands on the first box. ‘Do you mind?’

‘Of course not.’

He opened the box, took out the top item and handed it to Sarah. ‘Here she is.’

It was the Missing poster for Tania Mills. It had that elusive something that marked it as the past – a stiffness in the paper perhaps, or the sheen of a time when the Met outsourced such matters to a printing company, a dark, less sharp typeface, the smell of something stored too long in a box.

The poster bore a black-and-white black-bordered photograph of the missing girl, looking evenly at the camera. She was in her school uniform, with a too-fat diagonally striped tie and her hair in long plaits. Awkward, but pretty. The hotline number was for a London code long gone, superseded numerous times by the growth of the city and the changing nature of telecoms.

Stokes folded his arms across his chest. ‘To be honest, she’s been haunting me for nearly thirty years. I first worked the job as a young DC. I’m really hoping this new lead goes somewhere. Part of me wants to follow it up myself, of course. If you can solve it, I’ll buy you a case of champagne. That’s a promise. I’m a man of my word.’

Sarah wanted to offer some intelligent consolation. She put the poster back in the box, taking a moment before she spoke.

‘Surely it’s the fate of every serious detective to carry unfinished business into retirement? I’ve already got jobs that bug me and I’ve still got nearly twenty years to do.’ She smiled. ‘Not that I’m claiming to be serious myself.’

He shrugged, still looking at the poster. ‘I’ve got to let it go. I know that.’

‘What’s your feeling? Are you sure she was murdered?’

‘Well . . .’ Gently, he put the lid back on the box. ‘Her disappearance was so totally out of character.’ He opened his hands as if he were a magician with a disappearing trick. ‘And to never make contact again, never? Not in all this time?’

‘It does seem the most plausible explanation. But she could have had some sort of accident. Simply be dead, not murdered.’

‘Yes. That’s true. But still, no body.’

There was a silence. Then Sarah said, ‘And the family can’t stop hoping?’

‘Don’t really know about Dad – he doesn’t want updates unless it’s really necessary. Does everything over the phone. Finds it too painful to meet. As for Mum – she’s definitely got the candle lit at the window. Thinks it’s a betrayal to give up on Tania coming home.’

Sarah exhaled. Of course that was the case: hope was the last act of fidelity.

‘Have you told them about this latest line of inquiry?’

He shook his head. ‘I’ve told Dad but I’m leaving Mum to you, I’m afraid. I can’t stand to go through all that with her again. The hope, then the disappointment. We’ve had so much crap information over the years.’

‘They’re not together?’

‘Separated about twelve months after the disappearance. It’s often the way. I got into the habit of seeing Mum about once a year. We have a coffee. I tell her we never give up.’

‘Can’t be easy for you.’

‘No, it isn’t.’ He rubbed his right eyebrow with his index finger. ‘Still, hardly as difficult for me as for the family.’ He threw his hands out in sudden frustration. ‘Problem always was, no body! No physical evidence. No opportunity for a helpful DNA hit because the technology’s so much better now and the bastards didn’t know then that they hadn’t better leave anything of themselves behind.’ There was a brief silence. Then it seemed that Stokes couldn’t stop himself. ‘The job throws money at the cases that capture the public’s attention, but nobody’s interested in properly resourcing an obscure investigation into a fifteen-year-old girl who went missing more than twenty years ago.’

But it was normal, Sarah thought. How could the job possibly fund all of these missing people and lost causes? She checked her pessimism. She didn’t know yet whether it was a lost cause or not. And a new lead surely meant there would be some money on the table to investigate. It was her professional responsibility to hope.

Stokes, as if he was remembering to make small talk, glanced at the photo of the shiny black crow with the particularly beady eye. ‘Who’s that?’

Sarah smiled. ‘Oh that. That’s Sid – a former colleague.’

‘He didn’t fancy Homicide, then?’

‘No, he was a strictly Special Investigations kind of a corvid. They promised me they’d feed him.’

He tapped the photo of the spaniel. ‘And this little chap?’

‘That’s Daisy. I’ve only just got her. Don’t know what I was thinking.’

‘Looks like a nice dog.’

‘She is. A lot of fun.’

‘What do you do with her when you’re on duty?’

‘I’ve got a dog walker. She goes there full time when I’ve got a push on.’

Stokes nodded. ‘I remember when we used to be able to bring our dogs into work. CID nights there always used to be some mutt or other lying under a desk. Just one more thing we’re not allowed any more. Oh well, times change.’

For the first time Sarah felt his gaze focusing on her with the necessarily cool regard of a detective. It was an unconscious habit all the good ones had – to bring their professional attention to bear on non-professional matters.

He said, ‘You live alone, then?’

‘None of your business.’

She had tried for a bit of cheek in her voice but it wasn’t a style that came easily to her. Stokes had heard only her defensiveness.

‘Sorry,’ he said quickly. ‘Didn’t mean to intrude.’

‘No, not at all, no worries. Only joking. Yes, I live alone.’

She opened the Op Egremont box, removed the Missing poster, found some Blu Tack in her drawer and stuck the poster on the wall directly above her computer.

Stokes nodded. ‘Nice gesture. Thanks.’

‘No problem.’

She thought she had been giving him a clear message that the conversation was over, but perhaps his detective gaze had seen a trait in her that evoked sympathy because he now said, ‘Listen, Sarah. Don’t worry too much about Egremont. I never got round to it. Not properly. It’s just not possible. Once we pick up a live job, you’ll be too busy. You have to find a bit of space for down time.’

She tried to brush him off. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll only do what I can.’

But he wasn’t having it and interrupted. ‘This job can eat you alive.’

She offered her hand. ‘I’ll see you at the Crown later on.’

He enclosed her smaller hand in his two and smiled. ‘Look, this job, Tania Mills. I know you’ll give it a good go. I’m grateful. But don’t worry. I’m also realistic.’

‘Hey,’ she said. ‘It’s OK. I get it.’

He released her hand. ‘Sorry. I’ve got two daughters. Sometimes I need to be told to back off.’

‘That’s OK. But still, back off.’ She smiled.

He said, ‘You’ll like it here. And I’m sure you’ll do well. I’ve heard about you on the grapevine. I’d have liked to have worked with you. I admire someone who’s a bit bloody-minded.’

The door shut. Sarah slipped a capsule into the coffee machine, got out her reading glasses.

The disappearance of Tania Mills was an investigation that had long gone cold, but now, after all these years, there was a new lead. Erdem Sadiq, a prisoner on remand at Thameside, claimed to know what had happened. Sarah had wanted to interview the informant herself to get a measure of his evidence, but the DCI had told her it was too late for that.

‘We’ve already booked the interview. HMP will never let us change the officers at this stage. Don’t worry. I’m sending someone good: Lee Coutts. You’ll like him. He’s keen as mustard. Reminds me of myself as a young man. Anyway, don’t get too excited. The snout’s a sex offender – he’s got his own reasons for talking to us. This is something just to get you started. Work it slow time. Live investigations have to come first.’

Fedden hadn’t been encouraging, but he was right to be dubious about any information Erdem Sadiq might provide. Sadiq had a strong incentive to talk: if he gave evidence that led to a charge, he could expect time off his own sentence.

Sarah lifted the initial investigation summary out of the box. It was typewritten and bore Tippex corrections. The past felt so distant, so different, that it was hard to believe that she herself had been alive in 1987, throwing her satchel over her shoulder and walking to school with her older sister. As she began to read she reached back through the gap of time to that other girl who had walked out of her own front door on the morning after the storm, and disappeared.

Situation report: Operation Egremont

Victim: Tania Mills

Date of disappearance: 16 October 1987

Summary

Tania Mills left her home on 16 October 1987 at approximately 0900 hours. Tania’s school was closed due to the storm. Tania told her mother, Claire Mills, that she was going to see a friend, Katherine Herringham, to revise for her O levels. Tania frequently studied outside the home. Her parents had thought she would pursue a musical career but recently she had decided instead to study modern languages. Tania was known to walk to her friend’s through a local park. Katherine reported that Tania never turned up but that she hadn’t been worried because Tania often changed her plans.

Tania’s disappearance was reported at 1930 hours. Her mother, Claire Mills, told police she had expected her daughter home by 1800 hours but had not initially been concerned. Tania was fifteen, almost an adult. Claire had thought there was an innocent explanation for her delay in returning home.

By the time Tania’s father, Benedict Mills, returned home Claire was anxious. Benedict Mills drove to Ellerby police station and reported his daughter missing at the front counter.

Immediate action

Borough officers made an initial search of the park and surrounding area. The work was hampered by darkness and storm damage, including many fallen trees. Tania’s friends were contacted at their home addresses. None reported seeing Tania at all on 16 October. The following morning the investigation was taken on by the local CID. The park was cordoned off and an extensive search undertaken. A pair of jeans that had belonged to Tania were found. No other evidence was recovered. Robert McCarthy, the local park keeper, was arrested but subsequently eliminated from the inquiry. There was no sign of fighting or damage in any area of the park. No one reported seeing anything unusual. Tania’s school, Hachett’s, had reopened. Teachers and pupils were spoken to. An appeal was made in the local paper, the Ellerby Gazette, and on BBC London and Capital Radio . . .

The initial investigation and the subsequent reviews had generated hundreds of statements. And the files contained other things – exhibit lists, school reports, photographs. Sarah read for three hours. Still she felt she had only just started. She needed to get to know Tania, to reach out to her through the silent years. This wasn’t mere sentiment. It was her task as a detective to concentrate hard on every detail until the victim she had never met became a breathing person, revived for the sole purpose of rolling the film. It might be something hidden that unlocked what had happened – a criminal activity, a secret friendship perhaps – or it could be just a random detail. The victim made a detour to buy cigarettes or left the party early or left the party late.

Sarah was more dependent than usual on witnesses. In 1987, there had been fewer opportunities to intrude. Fewer cameras. No helpful internet browsing. No teenager’s phone accessed hourly to check her texts, update her status and tell an investigator where she was and who was important to her. She hoped the detectives had known their job: to cast their net widely and to encourage people to feel safe to speak.

Finally she stood up, rubbed her face, clasped her hands behind her neck and stretched backwards.

She was irritated by the investigation’s constantly repeated refrain that conjured a good girl – doing well at school, a talented musician – and very little else. Where were Tania’s misdemeanours? Where were the bits that made her a teenager – the untidiness, the day bunked off school, the secret smoking? Where, crucially, was the anomalous detail that might offer a fresh line of inquiry?

The only bit of grit that hadn’t passed through the sieve was an out-of-character shoplifting incident in Selfridges, six months before Tania disappeared. Tania had been arrested. Nothing had come of it. It wasn’t much but it might be worth probing. One other thing had drawn her attention. On the morning of her disappearance, Tania had secretly changed out of her jeans and into a short skirt. It was the last time police had evidence of her alive. Perhaps that moment too could stand some re-examination.

It was late afternoon and the other officers from her new team were already leaving, going straight to Peter Stokes’ leaving drinks. Still, she told herself, she could squeeze in a quick visit before that.

She made a phone call, shut down her computer, pulled on her jacket.

Sarah knocked at the front door of the house Tania had left nearly thirty years ago. She’d called ahead and driven the twenty minutes or so west to the nice suburban neighbourhood, the tree-lined residential streets.

The door opened. Claire Mills was in her late sixties and still trim. The first impression was of one of those well-turned-out women who can’t leave the house without foundation and lipstick. Neatly bobbed ashgrey hair. A blue brocaded jacket over a matching knee-length dress. Around her neck a Liberty-print scarf. It was the briefest of impressions. Tania’s mother quickly turned into the hall and guided Sarah inside, leaving her alone in the front room while she made tea. Still, despite the bright colours of the scarf, the smart clothes and the well-cut hair, Sarah had immediately recognized the immobility in Claire’s expression, the certain fixedness around her mouth and eyes: it was the imprint of settled grief shared by so many of the otherwise very different next-of-kins she had encountered. This woman’s life had been suspended in 1987. All her other activities gave only an illusion of movement around an unbending grief.

The front room – and it was a front room, not a sitting room – was a shrine.

One wall was covered with a Danish-style shelving system entirely devoted to the missing girl. A framed newspaper cutting of Tania with other girls all lined up holding a ball and wearing medals: U14s net prize in school netball competition. A Grade 8 certificate for violin, with distinction. Photographs in frames. Tania standing on a stage playing her violin in front of an orchestra. Tania – pinafore dress, white tights – curtseying by a piano and handing flowers to Princess Diana. Tania at the beach, a toddler with bucket and spade. Again at the beach, an older Tania – tiny breasts just budding – wearing a sailor one-piece with a white fringe around the hips and sporting red plastic heart-shaped sunglasses. There were objects too. A teddy bear. A small glass horse. The school music prize for 1986: a treble-clef music trophy.

Standing in the silent room, a thought suddenly came: Claire was holding the line but one day she would be gone too. All this memorabilia would become like a family video in a cardboard box of miscellanea in a junk shop that no one is interested in possessing, and the desire to find Tania would be silenced too.

The door to the hallway opened and Claire entered, carrying a tray with two china cups, a small teapot, a sugar bowl and milk jug, a plate of biscuits. She put the tray on the circular coffee table and smoothed down her dress with both hands before sitting.

‘Ben wouldn’t let me put photos up. He finds it easier than me to let go of things that cause him unhappiness. When he left I really let rip.’

Sarah mustered a smile and moved towards a chair. ‘I hope you don’t mind me looking.’

‘Not at all.’

She accepted the offered cup of tea. ‘They are lovely photos.’

‘Thank you.’

‘She was a violinist?’

‘Oh yes, very good. Grade 8 by the age of fourteen. With distinction. Everyone said she could play professionally.’

She’d trotted it out like an incantation. How many times had she said that since Tania had gone? ‘But she’d decided not to study the violin at college?’

‘Well yes, that’s right. I was pleased in a way. It’s very competitive. The better you get, the better everyone else is. Makes girls anxious. And all that practising! I thought she’d have more of a life if she kept it as a hobby.’

Sarah nodded, picked up the cue. ‘Was she a particularly anxious girl?’

Claire frowned, a tiny indentation between her brows. ‘Not particularly, no.’

You must miss her terribly.’

‘Every day.’

‘Would you tell me about her?’

Claire smiled – pleased, Sarah understood, to have the opportunity to say the words. ‘She was a lovely girl, absolutely lovely. Beautiful, talented, kind.’

Sarah nodded. ‘I want to ask you about something . . .’

Claire smiled again. ‘Ask whatever you like.’

‘Well, the morning she disappeared . . . she changed her clothing. After she’d left home, I mean.’

Claire shook her head in mock despair as though she was talking about a girl who had just that minute walked out of the room.

‘Teenagers! I’d said to her I thought her skirt was too short and she changed into jeans – only to please me, it turns out, because as soon as she was out of the house she changed back into the skirt.’

‘You don’t know anything more about it than that?’

Claire tilted her head, narrowed her eyes. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Why, should I? An arrest was made but they told me it was a mistake. Is there more to know?’

Sarah smiled. ‘No, not at all. I’m just new to the case and trying to get a better picture.’

There was a constrained smile. ‘That’s all right.’

Sarah paused. ‘There’s one other thing I wanted to ask you about . . . I hope you don’t mind.’

‘Please.’

‘There was a shoplifting incident, about six months before Tania went missing.’

Claire frowned again. ‘Oh, that. That was nothing! She’d gone into town, to Selfridges. She was at that age, you know? Beginning to experiment with how she dressed?’

‘Mmm. So what happened?’

‘She tried on a leather belt and left the shop without realizing she was still wearing it. Silly girl. Anyway, the officers accepted her account. Nothing came of it.’ After a moment’s pause, Claire added, ‘Do you mind me asking why you want to know about that?’

‘Like I say, I’m trying to get a feel for the case, for Tania. It’s just so out of character.’

‘Yes, though it isn’t really, because she hadn’t actually stolen anything.’

‘No. So, Selfridges, central London. That’s quite a way from here.’

‘Yes, but you know these girls . . . they’ve been raised in the city. They’re so confident with the trains and those department stores . . . they can try clothes, make-up, perfume.’

‘Was she with a friend?’

‘I don’t think so. On her own.’ There was a pause. Then Claire said, ‘If you think it might be relevant, you could ask my ex-husband. He went down to central London when she was arrested.’

‘Yes, I might do that.’

Claire’s mouth was tense. ‘He doesn’t want to talk about her, does he? Moving on. New family, all that.’

‘I’ve not met him yet.’

After an angry pause: ‘It was less than twelve months before he moved in with her. The first one, I mean. He’s on his third wife now. Nothing stops him.’

‘I see.’

‘I’ve wondered if they were already together – before Tania disappeared, I mean.’

‘And what do you think?’

‘I think they must have been, yes.’

‘But you don’t know for sure?’

‘Not for sure.’

Claire looked down and stretched her fingers out.

Sarah said, ‘I’m sorry to ask you this stuff.’

‘No, no, no. It’s fine. Don’t feel you have to treat me with kid gloves. Anything, anything at all that might help.’ She met Sarah’s eyes. ‘Biscuit?’

Among the Duchy Originals on the flowery china plate were Penguins in their shiny wrappers. Penguins splashing in water, penguins canoeing and skateboarding. Sarah leaned forward and chose a surfing Penguin. Claire took one too. They compared biscuits without comment. Claire’s penguin was skiing. They both smiled as they unwrapped them.

Sarah said, ‘Mind if I dunk?’

Claire put her own biscuit in her coffee. ‘Dunk away.’

The melted chocolate was over-sweet and brought memories of a plate of biscuits waiting on the kitchen table when Sarah came home from school.

Claire said, ‘They used to have shiny aluminium foil wrappers and the penguins were black and white. You can’t get those any more.’

‘You always keep a pack in the house.’

Claire nodded and Sarah knew better than to complete the thought.

For when she comes back.

Claire’s voice carried a hint of protest. ‘Sometimes missing people are found alive, even years afterwards. Jaycee Dugard, Natascha Kampush, Elizabeth Smart . . .’

She stopped speaking but Sarah’s imagination had already leaped unbidden to those girls, imprisoned, raped, but – finally – returned to their families. It was a poisoned dilemma. If you prayed Tania was still alive, then what were you praying for?

Claire was speaking again in a rush of words. ‘I know! I know how I must look to you. My silly Penguin biscuits! But if you knew. How I wish I could turn the clock back, stop her going out that door . . . ?

Sarah felt the tears come to her own eyes. She reached forward impulsively and put her hand on Claire’s knee. ‘You can’t imagine how happy it would make me to be able to find her for you.’

Claire looked directly into Sarah’s face. She nodded as if in surprised recognition of something she hadn’t expected to find there.

‘Thank you. Yes, I can see that. Thank you for that. Yes. Thank you.’

Sarah could hardly hear the words. She had, she felt, momentarily ceded control of herself. It wasn’t professional. She had lost the thread of why she was here, what she could offer. She sat back into her chair and into her mind came an unwelcome thought. This already means too much to me. There was another pause. Then Claire said, ‘Why don’t you tell me about this new line of inquiry you’ve got?’

Afterwards Sarah stood in the park just along the street from Tania’s house. The sky was gunmetal grey and the park was luminous with the strangely bright light that sometimes precedes showers. Perhaps she was doing it on purpose – making herself late for Peter Stokes’ farewell drinks – but no, she dismissed the thought. There’d still be time to pop in for a quick one.

She began to walk the route Tania’s school friends had said she normally took. The path wound downhill through trees. On the left was a children’s playground with horses on springs and a flying fox – new things. Sarah tried to picture how it had been on the morning Tania disappeared. She had seen the photographs: the uprooted trees, scattered branches, the turned earth.

Further down was the park keeper’s hut: a small building, shut up. Timber walls: planks layered vertically, green with lichen. Dirty floral curtains at a small square window. A padlock on the door. It was a ghost building. In 1987 this had been the fief of the investigation’s main suspect, Robert McCarthy. Sarah had read the account of his arrest more than once.

When police entered the park that first evening, Robert was there in the dusk: a slightly portly man who, at the age of thirty-five, was still dressed by his mother in cardigans and trousers with braces. He’d hung around. With a certain slackness around the mouth and that something about him that missed the point, he hadn’t matched the emotional state of the others looking for the lost girl. He’d got on people’s nerves.

The following day, when the park continued to be the focus of the police search, Robert was there again, bothering people, asking too many questions. He was the park keeper but no one seemed clear how he’d got the job. The park was only a small area of land and there was no real need for a full-time keeper. He was only paid an honorarium organized, it turned out, through the local church. Robert and his mother Pauline had been regular churchgoers. One of the more switched-on uniformed constables asked him for a cup of coffee.

Robert was honoured to have a big policeman in full uniform sitting in his hut. He gave the constable the best chair – the chair, he said, usually reserved for his mother – and made him a cup of instant coffee on his Calor Gas camping stove. PC Lawrence complimented Robert on how nice he kept everything. There was a big white plastic bottle for water, a little blue plastic bowl for washing up, a clean tea towel hanging on a hook. Some Matchbox cars were displayed on a shelf. There was also a folded pair of girl’s jeans on the table and Lawrence asked whose they were.

‘Tania’s.’

‘Tania’s?’ Then, after a pause, ‘How come you’ve got her jeans then?’

‘Because she came in here to change.’

‘To change?’

‘Yes.’

‘And why’ve you kept them?’

‘She forgot them. I want to give them back to her.’

The copper wrote in his statement that he had wanted to liaise with the investigators before taking any action but he had also not wanted to leave Robert in his hut where there might be more evidence that could be destroyed. So he nicked him. He used handcuffs because, although he was compliant, Robert was quite a big man.

Claire Mills was spoken to by detectives within the hour. She identified the jeans as the ones Tania had been wearing when she’d left home the previous morning.

Robert seemed quite happy in custody. He chatted with the police officers who gave him tea and biscuits. Pauline, his mum, came down and they were allowed a private word in one of the interview rooms. Pauline explained to Robert that the police just needed to find out everything they could. They would ask him some questions and he should tell the truth. Then everything would be sorted out. Robert didn’t need a lawyer because he hadn’t done anything wrong.

But Robert’s mood began to deteriorate when his mother was no longer allowed to act as his appropriate adult. As she had provided an alibi for him for the whole of the previous day, she was part of the evidential chain and couldn’t be involved in the interviewing process. Then a neighbour said she had cut Pauline’s hair in the afternoon and Pauline’s reliability as a witness was blown. She was arrested for perverting the cause of justice.

Robert saw his mother being booked in at the custody desk. It wasn’t clear to Sarah whether this had been done on purpose as a way of pressuring him. It had been a different time. Police had not been so aware of the dangerous suggestibility of vulnerable suspects. Robert told the interviewing officer he didn’t understand what was happening. He had always liked policemen. Many of his Matchbox cars were police cars.

A search of the hut turned up a photograph of Tania and Robert. Robert’s possession of the photograph was put to him in interview. He answered that he had the photograph because he loved Tania. She was special, not like the other girls: always friendly.

The interview was suspended. A warrant of further detention was obtained to enable further questioning. Detectives executed a warrant on Robert’s house. They found a collection of porn magazines under his bed. The local vicar, Reverend Byers, came down at Pauline’s request and acted as Robert’s new appropriate adult. The interviewing officers put it bluntly to Robert in interview that he had murdered Tania. Robert put his head in his hands and wept. There were so many tears that they had to get a cloth to wipe the table. Detective Constable Clarke asked Robert if he was crying because he felt guilty about what he had done. Robert replied that he didn’t feel guilty: he was crying because Tania was dead.

Clarke asked how Robert knew she was dead. Robert didn’t reply, only wept inconsolably.

Where had he hidden the body?

Robert started rocking with his eyes closed and his hands over his ears.

Robert was returned to his cell. The officers told the Reverend Byers they wanted to review the evidence, see if they had enough for charging.

The jailer brought a cup of tea to Robert’s cell and caught him masturbating. The jailer told him he should be ashamed. Tania dead and Robert was wanking? What kind of a monster was he? Perhaps the officer’s comments were understandable: he was only a young man and feelings were running high. There were posters of Tania everywhere. A press conference had been held earlier that day and the officer had seen it: Tania’s father frozen-faced, her mother sobbing, unable to get her words out. In any case, all hell broke loose. Robert tried to punch the jailer and then had to be restrained to stop him banging his own head on the cell floor. Even on a constant watch with a sympathetic female officer sitting next to him and a male officer standing at the door just in case, Robert kept weeping and rocking. The Reverend Byers asked to speak with the superintendent. He insisted his views be recorded. He entered them himself on the custody record in a beautiful italic long hand.

Robert, an adult with special educational needs, has been in detention for more than three days.

Robert has been masturbating in his cell. This is inappropriate but indicates his state of mind. I have known Robert for about eight years and have never seen behaviourlike this. His mental condition is clearly deteriorating under pressure. He is confused and distressed.

The evidence against Robert appears to be as follows. He had a photo of Tania and a pair of her jeans in his workplace – for which he has given an explanation – and some pornographic magazines at his home.

Questions remain unanswered. If Robert has killed Tania then how – with an IQ so low he can only read comic books – has he managed to conceal her body so effectively and in such a short period of time? How has he destroyed any evidence of violence on himself or elsewhere?

It is suggested that Robert’s distress is evidence of his guilt.

My view is that Robert wept in interview not because he knew Tania was dead but because he misunderstood the detective constable who accused him of murder. To a person with learning difficulties the accusation amounted to a perhaps unintentional misrepresentation of the evidence. Robert thought the police knew that Tania was dead.

Robert has told detectives that Tania was kind to him. She was unusual in taking the time to talk to him. Quite understandably, Robert loves Tania, and so, when he believed she was dead, he wept.