Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

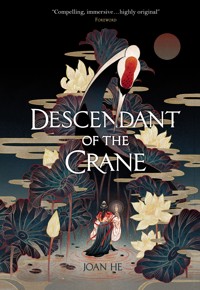

In this shimmering Chinese-inspired fantasy, debut author Joan He introduces a determined and vulnerable young heroine struggling to do right in a world brimming with deception. Tyrants cut out hearts. Rulers sacrifice their own. Princess Hesina of Yan has always been eager to shirk the responsibilities of the crown, but when her beloved father is murdered, she's thrust into power, suddenly the queen of an unstable kingdom. Determined to find her father's killer, Hesina does something desperate: she enlists the aid of a soothsayer - a treasonous act, punishable by death... because in Yan, magic was outlawed centuries ago. Using the information illicitly provided by the sooth, and uncertain if she can trust even her family, Hesina turns to Akira - a brilliant investigator who's also a convicted criminal with secrets of his own. With the future of her kingdom at stake, can Hesina find justice for her father? Or will the cost be too high?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for Descendant of the Crane

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Map

I Treason

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

II Trial

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

III Truth

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PRAISE FOR DESCENDANT OF THE CRANE

“Intricately plotted and beautifully written, Descendant of the Crane will demand your attention from start to finish.”

CHRISTINE LYNN HERMAN, AUTHOR OFTHE DEVOURING GRAY

“Descendant of the Crane completely swept me away. He's original voice is amplified by sophisticated storytelling and a captivating world. In a sea of young adult fantasy, this book stands on its own.”

ADRIENNE YOUNG, AUTHOR OFSKY IN THE DEEP

“Descendant of the Crane is my favorite kind of story: lyrical, romantic, politically complex, but most of all, driven by an iron-willed heroine who will do what must be done—no matter the cost.”

KRISTEN CICCARELLI, INTERNATIONALLY BESTSELLING AUTHOR OFTHE LAST NAMSARA

“Hesina is a heroine for the ages—brilliant, determined, and fierce. It is impossible not to root for her.”

LAURA SEBASTIAN, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OFASH PRINCESS

“[A] fast-moving debut... He combines a highly detailed Asian-inspired culture that incorporates Chinese names and traditions, aspects of top-notch thrillers, and complex characters.”

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Leave Us a Review

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones.com

or your preferred retailer.

Descendant of the CranePrint edition ISBN: 9781789094046E-book edition ISBN: 9781789094053

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London, SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition May 202010 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2019 Joan He. All rights reserved.Jacket illustration copyright © Feifei Ruan

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To my parents, whose sacrifices have made dreaming possible

I

TREASON

A well-conceived costume is a new identity, the father used to say as he put on his commoner’s cloak. From now until I return, I am no longer the king.

Teach me how to make a costume, begged the daughter.

He did that, and more. By candlelight, he divulged every way he knew of escaping the palace, for King Wen of Yan loved the truth, and little was found within the lacquer walls.

ONE

WHAT IS TRUTH? SCHOLARS SEEK IT. POETS WRITE IT. GOOD KINGS PAY GOLD TO HEAR IT. BUT IN TRYING TIMES, TRUTH IS THE FIRST THING WE BETRAY.

ONE OF THE ELEVEN ON TRUTH

TRUTH? WHY, IT’S A LIE IN DISGUISE.

TWO OF THE ELEVEN ON TRUTH

No night was perfect for treason, but this one came close. The three-day mourning ritual had ended; most had gone home to break the fast. Those who lingered in the city streets kept their eyes trained on the Eastern Gate, where the queen would be making her annual return.

Then came the mist. It rolled down the neighboring Shanlong Mountains and embalmed the limestone boulevards. When it descended into the bowels of the palace, so did the girl and her brother.

They emerged from the secret passageways the girl knew well—too well, perhaps, given her identity—and darted between courtyard compounds and walled wards, venturing toward the market sectors. When they arrived at the red-light district’s peeling archway, an ember sparked in the girl’s stomach. Some came to the seediest business quarter of the imperial city to buy warmth. But she?

She had come to buy justice.

Her brother held her back before she could cross. “Milady—”

If he called her “milady” out here, he might as well call her Princess Hesina. “Yes, Caiyan?”

“We can still go back.”

Hesina’s fingers closed around the glass vial dangling from her silk broad-belt. They could. She could let her resolve fade like the wisp of poison bottled in the vial. That would be easy. Figuring out how to live with herself afterward…not so much.

Grip hardening, she turned to her brother. He looked remarkably calm for someone risking death by a thousand cuts—crisply dressed despite the rough-hewn hanfu, every dark hair of his topknot in place.

“Having doubts?” She hoped he’d say yes. At fifteen, Caiyan had passed the civil service examinations. At seventeen, he’d become a viscount of the imperial court. At nineteen, his reputation was unparalleled, his mind more so. He wasn’t renowned for making bad decisions—unless they were in her name.

“How would you find the way?” asked Caiyan, countering her question with one of his own.

“Excuse me?”

Caiyan raised a brow. “You’re hoping that I’ll say ‘yes’ so you can proceed alone. But that wasn’t our agreement. I am to lead the whole way, or I don’t take you to this person at all.”

Our agreement. Only Caiyan could make treason sound so bland.

“I won’t be able to protect you.” Hesina scuffed one foot over the other under the hem of her ruqun. “If we’re caught… if someone sees us…”

A man bellowed an opera under the tiled eave of a dilapidated inn, and something porcelain shattered, but Caiyan’s voice still cleaved the night. “You don’t have to protect me, milady.” Red lantern light edged his profile as he looked into the distance. “He was my father too.”

A lump formed in Hesina’s throat. She did have to protect him, in the same way her father—their father—had. You can’t possibly touch all the lives in this world, he’d told her that winter day ten years ago when he’d brought the twins—slum urchins, one thin girl and one feverish boy—into theirs. But if you can lift someone with your two hands, that is enough.

Hesina wasn’t lifting Caiyan up; she was leading him astray. But when he reached for her hand, she held on, to her dismay. The confidence in his grip grounded her, and they crossed into the district together.

They entered a world of slanted teahouses and inns, brothels and pawnshops clustered like reeds on a panpipe. Men and women spilled out of the paper-screened doors, half-clothed and swinging certain appendages. Hesina averted her gaze and pressed closer to Caiyan.

“It’ll get better up ahead.” Caiyan had once called streets worse than these home, and he guided them around peddlers with impressive ease. He didn’t pay any mind to the occasional beggar, not even the one who tailed them down the block.

“Beware the night,” cried the man, shaking coins in a cracked ding pot. Hesina slowed, but Caiyan tugged her along. “Beware the rains, the crown, and the Sight!”

“Ignore him.” Caiyan’s gaze glowed with focus. “He speaks of the bygone dynasty.”

But on a night like this one, the past felt uncomfortably close. Hesina shivered, thinking of an era three centuries ago, when peasants had drowned in summer floods and perished in winter famines. The relic emperors had pursued concubines, conquests, and concoctions for immortality, while their imperial soothsayers Saw into the future to crop resistance before it could sprout. As for the sick and the starving, too weak to resist, the sooths placated them with visions of the brilliant tomorrows to come.

And they did come—at the hands of eleven scrappy outlaws who climbed the Ning Mountains, crossed the Kendi’an dunes, breached the imperial walls, and beheaded the last relic emperor on his very throne. They emancipated serfs and set them to work on dikes and embankments. Storms calmed. Floods drained. They opened the doors of education to women and commoners, and their disciples circulated the former outlaws’ philosophies in a book called the Tenets. The people of Yan called them the Eleven. Legends. Saviors. Heroes.

“Beware the devil of lies.”

Of course, heroes cannot be forged without villains: the emperor’s henchmen, the sooths. The Eleven rooted them out by their unique blood, which evaporated quicker than any human’s and ignited blue. They burned tens of thousands at the stake to protect the new era from their machinations.

Whatever the reason, murder was murder. The dead were dead. Hating the sooths, as the people continued to do, made little sense to Hesina. But occasionally, like now, with the beggar barking ominous warnings, her pity for the sooths spawned into fear, eating away at her conception of a sooth until it collapsed and a new one rose in its place: a faceless head attached to a charred body, an eyeless, toothless monster straight from the Ten Courts of Hell.

By the time Hesina eradicated the image, the beggar was gone and another had taken his place, resuming the chants—in an all-too-familiar female voice.

“Beware the one you leave behind.”

Oh no.

Hesina whirled as a hooded figure strode toward them.

“My, my. What do we have here?” The newcomer circled Hesina. “I like the linen ruqun. Very commoner-esque. As for you…” She flung aside Caiyan’s cloak and frowned at the plain hanfu beneath. “This is how you try to pass as a sprightly nineteen-year-old in search of a romp? What are you, a broke scholar?”

Caiyan readjusted his cloak. “We’re going to a music house.”

The newcomer placed a hand against her hip. “I thought you said ‘brothel.’”

“I said no such thing.”

“I could have sworn—”

“I thought,” Hesina gritted out, overcoming her shock and glaring at Caiyan, “you were to say nothing about this to anyone.”

Caiyan, in turn, glared at the newcomer. “You said you wouldn’t come if I told you.”

“You should have known better!” cried Hesina, and Caiyan pinched the bridge of his nose.

“I know, milady. Forgive me.”

“Now there, Na-Na.” The newcomer lowered her hood and fluffed out her braids. Pinned back like a pair of butterfly wings and woven through with bright ribbons, the braids were a signature part of Yan Lilian’s style. So was the mischief in her eyes, a shade of chestnut slightly lighter than her twin Caiyan’s. “The stone-head tried. It’s not his fault that I blackmailed him. Besides, did you really think I’d let you commit treason without me?”

Hesina wasn’t sure whether to be angry or miserable. “This isn’t a game.”

“You promised.” Caiyan sounded mostly miserable.

Lilian ignored him and faced Hesina. “Of course it’s not a game. It’s a dangerous, important mission befitting a threesome. Look at it this way: you need one person to hear this forbidden wisdom, one to watch the door for intruders, and one to beat up the intruders.”

“Send her away,” Hesina ordered Caiyan.

Lilian danced out of Caiyan’s reach. “I could still tell all your high-minded court friends that the illustrious Yan Caiyan reads erotic novellas in his spare time. Who’s the latest favorite? Wang Hutian?”

Caiyan made a strangled sound. Lilian laughed. Hesina watched their shadows lengthen under the moonlight.

They were losing time.

“Let’s walk,” said Lilian, as if reading Hesina’s mind. She linked their arms. “You can try to get rid of me on the way.”

Hesina knew better than to try. They proceeded in silence, the low-lying shops on either side giving way to taller, pillared structures. The song of zithers and pipa lutes replaced drunken improvisations.

“You shouldn’t have come,” Hesina finally said.

“What’s life without a bit of danger?”

“Be serious.”

“I am, Na-Na.” Like a real sister, Lilian still used Hesina’s diminutive name long after she’d outgrown it. “Father might be gone, but he won’t be forgotten. Not with us here.”

“That’s…” Comforting. Frightening, that Hesina had more loved ones to lose. “Thank you,” she finished hoarsely.

“Well, we might not be here for much longer, since meeting with this person may end in death by a thousand cuts.”

“Lilian!”

“Sorry. Sorry. Pretend I didn’t say that.”

Ahead of them, Caiyan stopped in front of a three-tiered building. From the outside, it resembled one of the celestial pagodas rumored to exist back when gods walked the earth. But inside, it was every bit a music house. Beaded curtains fell from the balustrades. Private rooms blushed behind latticework screens. The namesake music—plucked and bowed—gusted through the air, fanning Hesina’s anxiety.

“Don’t look anyone in the eye,” Caiyan instructed as they crossed the raised threshold and came into the antechamber. “And don’t take off the hood of your cloak,” he ordered, right before lowering his.

“Welcome to the Yellow Lotus,” said a madam, weaving toward them through flocks of painted girls and boys. Her smiling, moonlike face dimmed when she neared Caiyan. “First time at this establishment, I presume?”

Lilian coughed.

“Let’s see…” The madam scanned the courtesans. “The White Peony might be to your liking—”

“We’re here to meet the Silver Iris,” cut in Caiyan.

The madam frowned. “The Silver Iris is our most highly sought-after entertainer.”

“So I’ve heard.”

“She has mastered the golden triad of calligraphy, music, and dance.”

“Again, so I’ve heard.”

“She is choosy with patrons and has limited hours.” The madam leaned in and, with a long, emerald-varnished fingernail, extracted a loose thread from Caiyan’s cloak. “Her gifts are wasted on the likes of you.”

Hesina gulped.

Without batting an eye, Caiyan withdrew a brocade purse. “Is this enough?”

The madam snatched it, loosened the drawstring, and peered in. Hesina couldn’t tell what the woman was thinking, and as the madam bounced the purse up and down in her ringed hand, she sweated through her underclothes.

At last, the madam scrunched the purse shut. “Come with me.”

As she led them up a set of purple zitan-wood stairs and rapped on one of the many doors lining the second-floor corridor, Hesina pinched her own wrist. For five nights, she’d tormented herself with questions. Was it right to do this? Was it wrong? If it was, then was she angry enough, sad enough, selfish enough to see it through regardless? She didn’t know. She’d gotten this far, and she still didn’t know. But now only one question remained: Was she brave enough to hear the truth?

Hesina knew her answer.

The madam rapped again, harder, and a husky voice unfurled from within. “Yes?”

“You have guests.”

“How many?”

“Two,” said Lilian. She leaned against the wall beside the door. “I’ll be right out here.”

“Have they paid?”

The madam moistened her lips. “They have.”

“Leave them, then.”

Nothing happened immediately after the madam departed. The doors didn’t open. Demons didn’t descend from the beamed ceiling to exact their punishment, but as they waited, Hesina’s mind produced demons of its own. Maybe they’d been followed. Maybe someone had recognized her. Maybe—

The doors parted, and her demons fled before treason’s face.

It was an exquisite face. Ageless. Pearlescent. Silver-lidded eyes skimmed past Hesina and landed on Caiyan. Rose-tinted lips crimped in displeasure, and Hesina had all of a heartbeat to wonder how, exactly, Caiyan was acquainted with a courtesan before she was ushered past the doors. The courtesan bolted them, the ivory dowel falling into place like the final note of a song.

Hesina, unfortunately, was much too prone to nervous laughter. In an attempt to ignore the tickling tension in her chest, she fixated on the chamber. A gallery of pipa hung on the walls, their scrolled necks knuckled with ivory frets, strings drawn tight over their pear-shaped bellies. Four-word couplets papered the remaining space. To her embarrassment, Hesina only recognized one from her studies.

Downward unbridled water flows;

Upward unrealized dreams float.

“I assume you’ll want to skip the tea.”

Hesina nearly jumped at the Silver Iris’s voice, which was as metallic as her name.

“That’s correct,” said Caiyan, standing against the door.

“Then let’s have a little demonstration, shall we?”

That won’t be necessary, Hesina imagined saying with grace and magnanimity, but it was a lie, and the Silver Iris knew it. A hairpin was already in the courtesan’s hand. She pushed her finger into its needle-sharp tip, then held the pin over an unlit candle. A bead of blood fell and burst on the wick.

A wisp.

A spark.

A flicker.

The wick ignited into blue flame.

Hesina’s vision swam. The flame blurred, but stayed blue.

Blue. Blue. Blue.

“A nice parlor trick, don’t you think?” asked the Silver Iris. Her tone was conversational, but her gaze picked Hesina apart, straight to the core of who she was: a descendant of murderers.

Hesina’s stomach clenched. She wasn’t supposed to think the Eleven cruel. They’d built a kinder era, a fairer era—one where individuals were judged by their honest work, not the number of sooths and nobles they knew. Everyone was promised rights by the law—everyone but the soothsayers, who had manipulated the public for so many centuries. Death by a thousand cuts was considered kind for them…and for the people who employed the sooths for their gifts.

People like Hesina.

The Silver Iris sat and gestured for her to do the same. Weak at the knees, Hesina sank onto the silk-cushioned stool. She realized, somewhat belatedly, that she had yet to reveal her face. The disguise seemed silly now. A child’s game. She looked to Caiyan in question while the Silver Iris swaddled her finger with a handkerchief.

The courtesan spoke before Caiyan could. “So tell me, Princess Hesina.” She balled up the bloodied handkerchief and tossed it into the brazier at their feet, where it promptly burst into flame. “What is it that you wish to see?”

TWO

TOO MUCH OF A THING—BE IT SUCCESS OR POWER—ROTS THE HEART.

ONE OF THE ELEVEN ON SOOTHSAYERS

THEY HAD NO HEARTS TO BEGIN WITH.

TWO OF THE ELEVEN ON SOOTHSAYERS

With shaking hands, Hesina pushed back her hood.

She had come to see the future. The unknown. Yet for a second, all she could see was her father, lying in the iris beds, wearing his courier costume. She wasn’t sure how long she’d waited. Waited for him to rise and yawn, to tell her how lovely it was to stroll through the grounds in disguise. Waited for herself to wake when he never did.

That day, Hesina had watched as the Imperial Doctress took up a scalpel, splitting the dead king’s stomach like a fish. There was nothing to find, not at first. The Imperial Doctress concluded that the king’s death was of natural causes before puttering off to the adjacent chamber.

If only she had stayed a second longer to witness the golden gas rising from the slit. If she had believed when Hesina tried to show her the wisp in the vial, then Hesina wouldn’t be here. Her hands wouldn’t be clenched in her skirts just as they’d been clenched around the Doctress’s robes.

Her voice wouldn’t be so strained when she asked the Silver Iris, “Who killed my father?”

The Silver Iris blinked once. “Killed?”

“Yes, killed!” Hesina choked up. “The king didn’t die a natural death. The decrees lie.”

But she would show the kingdom the truth. With the Silver Iris’s Sight, she would find the assassin, press them into the tianlao dungeons, and maybe then, when she had a life for a life, this nightmare would—

“I See golden gas rising from a pile of shards,” the Silver Iris started. Hesina leaned in. “But I can’t See who killed the king.”

Hesina’s heart dove like a kite without wind.

“What I can See is the person who will help you find the truth.”

“A representative?” Hesina couldn’t mask her disappointment.

“Yes.” The Silver Iris smoothed an embroidered sash over her knee. “You could call him that.”

Hesina wound the cord connecting the vial to her broad-belt around her thumb. If she chose to follow a path of formal justice for her father’s killer, the Investigation Bureau would look into Hesina’s claim that he’d been murdered. Once they’d officially forwarded the case to the court, the Minister of Rites would assign a representative to both the plaintiff—in this case, her—and the defendant.

“Well?” prompted the Silver Iris. “Would you like to hear?”

Princesses were not so different from beggars. Hesina had learned to take what she could get. “Yes.”

The Silver Iris’s doe-like eyes roved over her. Hesina squirmed, well aware there was nothing impressive about her appearance. She lacked the hunger for knowledge that flamed in Caiyan’s eyes, the mirth of Lilian’s lips. A visiting painter had once said that Hesina had her mother’s face, but they both knew she’d never wear it as well as the queen. Hesina thought she heard similar sympathy in the Silver Iris’s voice when she finally said, “A convict.”

“A…convict.” The cord had cut the circulation to Hesina’s thumb. She unwound it, pins and needles replacing the numbness. Her father’s justice…handed to a convict.

She almost laughed.

“I’m sorry.” Hesina’s composure would have made her tutors proud. “There must be a mistake.”

The Silver Iris drew back. “No mistake. A convict will represent you in court.”

“That’s impossible.” Only up-and-coming scholars, selected from a pool of hopeful civil service examinees, acted as representatives in trials. The court was a stage on which to prove their intellect; the reward for winning the case was a free pass through the preliminary rounds of the examinations. The Eleven had made it so to give every literati a chance to rise, regardless of family background. But what did a criminal have to gain from such a system?

Hesina’s disbelief condensed. “Please look again.”

“You think I’m lying.”

“What? No.” Hesina didn’t believe the Silver Iris would lie, not really, for the same reason people trusted sooths in the past. Though books and libraries on the specifics of their powers had been destroyed in the purge, select legends had lived on to become common knowledge. One was that sooths couldn’t lie about their visions without shortening their life spans. How else, argued scholars, could the relic emperors have controlled them?

“Why not?” The Silver Iris rose and turned her back to them. A cascade of colors tumbled out from the hidden layers of her lilac skirt. “Do you think I’m scared of shaving a few years off my life?”

She loosened her sash, and the ruqun puddled onto the lacquered floor.

First came the hand-shaped bruises, flowering over her bare back. Then came the burn marks. Hundreds of thin, puckered lines, as if someone had bled her with a knife and watched her smoke for the fun of it.

“Some would rather see us alive than cut to a thousand pieces or charred at the stake,” she said as Hesina’s throat closed. “You assume I tell the truth because I fear death, but the dead are lucky. They cannot squirm or shudder.” She made for her wardrobe. “Nor can they be forced to say the things you want to hear.”

The brazier at Hesina’s feet was still spitting flame, but her toes had gone cold. She shouldn’t have come here. The Silver Iris had bled for her and Seen for her, but Hesina had given her no choice, just like the patrons before her. She staggered out of her seat.

“I…I’m sorry. I never…I never meant…We’ll leave—”

“A convict.” The Silver Iris slid on a different ruqun—this one sheer and crimson—and tied it shut with a braided cord. “The one with the rod. That is all I can see. My blood is diluted. Few of us are as powerful as our ancestors. But you already knew that, didn’t you?”

Meaningfully, she met Hesina’s gaze in the bronze mirror atop her vanity.

Hesina’s mouth opened and closed. No words came out.

A rap sounded at the door, then Lilian’s voice. “Someone’s coming up the steps.”

“You should go now.” The Silver Iris opened a drawer, withdrawing a tiny pot. She unscrewed the top and dabbed a fresh coat of silver over her lids. “I have patrons to tend to.”

“Y-yes,” stammered Hesina. “We’ll go. I…I’m sorry.”

She backed up. Caiyan joined her side. He held the door open for her, but suddenly Hesina couldn’t move. A question rooted her, climbing up her esophagus like a weed and choking her mind:

“Why tell me anything?”

“What makes you so certain I haven’t been lying to you all this time?” asked the Silver Iris, gaze chilly.

Because Caiyan said you wouldn’t. Because rumor said lying would cost you.

“Because you showed me more than I deserve,” said Hesina truthfully. “And…” She bit her lip and looked away. Naive, the Imperial Doctress had called her. Reckless. “And because I want to trust you.”

Because I feel sorry for you.

The Silver Iris sighed. “Come here.”

Hesina went over cautiously, and the Silver Iris held out her index finger.

The prick from the hairpin was gone. As small as the wound was, there was no way it could have healed so quickly, and Hesina goggled at the smooth, unmarred skin, flinching when the Silver Iris’s breath brushed her ear.

“Your histories only tell you how our powers hurt us,” whispered the courtesan. “But there are benefits to speaking true visions too.”

She drew back, leaving the shell of Hesina’s ear hot and cold all at once. “Why are you telling me this?”

When the Silver Iris studied her this time, the ice in her gaze had thawed to pity, as if she were the human and Hesina were the sooth. “For the same reason you believe me: I am sorry for you.”

* * *

They left the red-light district at two gong strikes past midnight. Left and right through the eastern market, merchants packed up their stalls, loading jiutan of sweet-wine congee and fried bean curd back onto wagons. Hesina drifted through the traffic, a ghost, as Caiyan pacified angry mule drivers and palanquin bearers.

“Hey, watch it!”

“Are you trying to lose a leg?”

“I’m terribly sorry,” said Caiyan. “Excuse us. Pardon us.”

“Tell your missy to grow a pair of eyes!”

“Wait up, Na-Na,” called Lilian.

Hesina didn’t stop. She needed to think, and she couldn’t think standing still.

A convict with a rod was to be her representative.

The Silver Iris had told the truth.

But now what?

Her feet brought her to the abandoned tavern from which they’d come. Her hands filled a pitcher at the counter pump. She dribbled water down the throat of the concrete guardian lion at the entrance, and the statue rotated aside at the base.

One by one, they descended the tight drop. The dark waxed over them as Lilian rotated the statue back in place, and Hesina suddenly knew her next steps.

“I need to become queen.” She made her declaration to the humble dirt walls of the underground passageway. Her voice echoed, hollow as the feeling in her chest.

“Of course you’ll become queen,” said Lilian, referring to the rites of succession that passed the throne from deceased ruler to eldest child.

“When your mother returns from the Ouyang mountains, you can ask for her blessing,” said Caiyan, referring to the tradition of parental validation that all heirs, imperial or not, observed before staking their claims.

The twins went back and forth as they walked down the tunnel. Rites. Traditions. Rites. Traditions. Neither seemed to realize that Hesina had said she needed the throne, not that she wanted it.

She envied Lilian, who was allowed to spend her days overseeing the imperial textiles. She envied Caiyan, who positively breathed politics. She even envied her blood brother Sanjing, who led the Yan militias. The throne never stood in the way of their hopes and dreams.

But for the first time in her life, Hesina had a use for power.

“I want an official investigation.” Her father would have wanted the truth delivered by the codes of the Tenets. That meant going through the Investigation Bureau, not a sooth. “I want a trial.” The ground rose beneath their feet as they approached the end of the passageway. “I want the people to see the truth unfold in court.”

“So you really think there’s a convict with a rod?” asked Lilian as they emerged from a miniature mountain range situated in the center of the four-palace complex.

There was only one way to find out.

“Go on without me.” Hesina turned north, toward the dungeons.

Caiyan caught her elbow. “It’s best to visit at a less suspicious hour.”

Lilian took her other elbow. “For once, I agree with the stone-head. Commit one act of treason at a time.”

Better yet, commit no treason at all.

Hesina shook them both off. “I didn’t say I was going to make him my representative right now.”

If only it were that simple. To prevent the rich and powerful from hiring the best scholars and winning every case as they had during the relic dynasty, the Tenets ordered that plaintiff and defendant each be assigned a representative at random. As a result, Hesina couldn’t choose her own representative. It was treason. Convincing the only person in charge of the selection—Xia Zhong, Minister of Rites, Interpreter of the Tenets—happened to be treason too.

But that, Hesina decided, was another problem for another night.

“What are you going to do in the dungeons, then?” Lilian was asking when Hesina emerged from her thoughts. “Examine his rod?”

Caiyan cleared his throat.

Hesina patted Lilian on the arm. “I’d save you the honors.”

“I’m holding you to that.”

“It’s late, milady,” said Caiyan, changing the subject. “The prisoners won’t be going anywhere. Wait for tomorrow, when your mind is clearer.”

Don’t wait, growled the fear in Hesina’s belly. She’d been too late to save her father, too late to stop news of his “natural death” from circulating the kingdom.

But Caiyan had a point. The night was balmy with the last of the summer heat, and Hesina’s senses had begun to fog. Their trip into the red-light district felt like it’d taken place an eon ago, and she couldn’t hold back her yawn when they reached the Western Palace, home to the imperial artisans.

Under a medallion-round moon, Lilian bade them good night. The woodwork of her latticed doors was stained fuchsia and gold, bright like the textiles strewn, hung, and piled within. It was like looking into another world, a too-short glimpse of a life Hesina could not have. The doors slid shut, and Hesina and Caiyan continued on, traveling under the covered galleries that converged like arteries at the Eastern Palace, the largest of the four and the heart of court. The sunk-in ceilings dropped lower as they passed the ceremonial halls of the outer palace, the corridors narrowing as they approached the inner.

Caiyan stopped Hesina short of the imperial chambers. “Lilian and I will stand by you no matter what you choose to do.”

The words were bittersweet, reminding Hesina of something her father might say.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “For everything.”

Caiyan hadn’t doubted the gas in her vial. She’d run to his rooms in hysterics and he’d sat her down and outlined her options. Steady, reliable Caiyan, a friend, a brother, who received her gratitude with a short bow. “Get some sleep, milady.”

“You too.” But then Caiyan headed in the direction of the libraries, which made Hesina doubt he would.

Alone, she made for her chambers. The path to the imperial quarters was intentionally convoluted, designed to confuse intruders. Tonight, Hesina felt no better than one as the knit of lacquer corridors enmeshed her within the screened facades. Some of the images stitched upon the translucent silk were of water buffalo tilling rice paddies, but most were of the Eleven’s revolution. Gold thread fleshed out the flames engulfing the soothsayers and shimmered in the pool of blood spreading from the relic emperor’s severed head.

Hesina’s breath went ragged. Don’t fear the pictures, Little Bird, her father would have said. They’re simply art. But now she was as bad as the emperors of the past. She had used a sooth. Worse, her true heart sympathized, and she was too cowardly to speak it.

Hesina tried to look ahead. A mistake. The list of tasks awaiting her was daunting. Find the convict with the rod. Persuade Xia Zhong to choose him as her representative. Secure her mother’s blessing and commence her reign by telling the people their king had been murdered.

She would be an unforgettable queen—if she didn’t die by a thousand cuts first.

As Hesina neared her chamber, her blood slowed to a crawl. Light was seeping out from under the doors. She’d blown out all her candles—she was sure of it—which could mean only one thing:

Someone was inside.

Pulse fluttering, she laid a hand atop the carved wood. Her options were few. Walk away, and her visitor would think she’d been gone all night. Enter, and she’d have no choice but to explain her whereabouts.

On second thought, perhaps she hadn’t blown out her candles. Hesina very much hoped that was the case as she pushed in.

“Sanjing?” Her mouth fell open while the doors swung shut. “What are you doing here?”

Candlelight rippled off the scales of her blood brother’s laminar armor as he rose from her daybed. He was still in full military dress, hair pinned in a sloppy topknot, curved liuyedao sheathed at his leather broad-belt.

He stalked past her embroidered screens and around her sitting table. “You first, dear sister. What have you been doing elsewhere?”

He closed in. Too late, Hesina realized the state of her appearance—brown cloak, wild eyes, the fumes of sin city clinging to her hair.

She backed away, but her brother was quicker. He grabbed a handful of her cloak, frowning when his fingers met linen instead of silk. He brought the fabric to his nose, and her heart hammered. She tried to slow it. Sanjing was kin. He wouldn’t betray her to death by a thousand cuts.

“You went to the city. And you reek of incense.”

Hesina’s fear frayed into annoyance. She was the older sibling, and she drew herself up to her full and very average height. “Glad to know you care about my whereabouts. What next? Will you supervise who I speak to?”

“Why would I? You already have a devoted chaperone.” Sanjing released the cloak, and Hesina retreated to her desk. “Or should I say, manservant.”

She straightened her paperwork. Decrees, proposals, memorials—all matters that fell to her while she acted as unofficial queen before the coronation, and in the absence of her mother’s blessing. But no matter how Hesina concentrated, she couldn’t stop trembling. Elevens. Why did Sanjing have to be here, now of all times? “His name is Caiyan.”

“Really? I still prefer the sound of manservant. Has a nice ring to it.”

Her hands stilled on a copy of the Tenets. It was solid, thick with hundreds of essays on the Eleven’s beliefs. It withstood the pressure of her fingers as she dug them into the spine.

She could be cruel. Dredge up the past they’d both agreed to bury, say the words guaranteed to drive him away. But in the end, she simply set down the tome with a heavy thump. “Why are you here, Jing?”

“Again: why weren’t you?”

“I went to find justice.”

“For?”

Her limbs were cold, her head heavy. She was too tired for this. Maybe that’s why she told the truth. “Father.”

She drew the vial from the folds of her cloak. The golden gas shimmered in the candlelight.

“What is that?” asked Sanjing, squinting.

“Poison.”

He hissed in a breath. “Why am I learning this now?”

“You really thought he died from natural causes?”

“I didn’t think the Imperial Doctress had a reason to lie.” Sanjing scrubbed a hand over his face. “Six’s bones. What are we going to do?”

Hesina’s hopes lifted at the we, but it wasn’t enough. The better question was what could they do. It was their word and a vial against a kingdom already convinced its king had passed peacefully. Again, she needed the throne. She needed power. Once she had both: “Open an investigation.”

“With the Bureau?”

“Where else but the Bureau?”

Sanjing narrowed his eyes. “What about the war?”

“What about the war?” Then Hesina caught herself. “Don’t call it that.”

“What would you rather call it? A pissing match?” She cast him a warning glance, and he responded, “We’re alone, Sina.” Sanjing planted his hands on the desk, boxing in the space between them. “What we call it doesn’t change the nature of the ‘bandit raids’ along the Yan-Kendi’a border. They’re planned attacks from Kendi’a, and the commoners will realize that sooner or later.”

“They mustn’t.” The Tenets forbade war, and understandably so. The relic emperors had conscripted hundreds of thousands of serfs to wage extravagant campaigns against the other kingdoms of Ning, Ci, and Kendi’a, and the commoners of this era hadn’t forgotten the bloodshed. They praised Sanjing whenever he won skirmishes—skirmishes being key. Every century or so, some Yan king or queen would disregard the Eleven’s pacifist teachings and decree war, sending hamlets and provinces across the realm into revolt.

“Yan has water,” said Sanjing. “Kendi’a does not. Their steppes grow drier and drier with the years. Invasion is inevitable, and we need to be ready to meet it with an army. The Tenets forbid wars fought for gain; we fight for self-defense. But starting a war and officially declaring that the king was murdered? Don’t you see the issue?”

No, Hesina did not. “The people will want to know who killed their king,” she said, more certain of this than anything else.

Her brother’s eyes flashed. “They’ll want a scapegoat, Sina.”

“They’re better than that.”

“What makes you so certain?”

“Father loved them.” In the same way he loved her—regardless of her flaws, teaching by example.

“Father wasn’t always right.”

Hesina stared at her brother as she would a stranger. When had they grown so far apart that they’d stopped seeing eye to eye on this too?

“We should start by examining the poison on our own,” Sanjing continued. “Find the truth for ourselves—”

“What’s wrong with you?” Hesina hadn’t shouted, but Sanjing stiffened as if she had. “Why do you have so little faith in our court?”

His expression hardened. “Because of this.”

He tugged papers out from under his breastplate and tossed them onto her desk. They spread like the wings of a crane, scattering on impact. Some landed on the floor.

Under the heat of Sanjing’s gaze, Hesina bent and gathered the papers that had fallen. She stacked them with the rest, shuffling everything into place, and grudgingly gave her attention to the contents.

“I didn’t want to show you this,” said Sanjing as she tried to make sense of what she was reading. “I figured it’d make you worry. But it’s time you opened your eyes.”

The papers were pages torn from a copy of the Tenets. But the characters scrawled between the vertical columns of text weren’t commentary or critique. They were reports—fine-grained accounts detailing the security and transportation systems of several borderland towns, information that would have been very helpful to a Kendi’an raiding party.

Only a Yan official could have written these letters.

“My scouts confiscated several suspicious bundles before they could cross into Kendi’a. These letters were hidden among the tariff reports, in a chest stamped by the Office of the Imperial Courier. Someone in this palace has been helping the Kendi’ans terrorize our villages. Someone wants a war. Hand them a murder case, and they’ll hand you a Kendi’an.”

Sanjing sounded far away. His words circled Hesina’s head like wasps. Or gnats. It was the latter, she decided, setting the letters down on the desk. Gnats were harmless. “There are hundreds of officials in this court, most of them unimportant,” she said. “One person cannot obstruct the course of justice.”

“And what if they are important? What if they have friends?”

All conjecture. Hesina waved it aside. “You have no way of knowing. Besides, if we withheld cases from the Investigation Bureau for every small quibble, would we still have a court?”

“This is different. A king has never been killed before.”

“He was our father before he was the king. We owe this to him. Enough.” Hesina raised a hand before her brother could go on. “Ride to the borderlands. Take five thousand militiamen and women with you, and see if you can quell the raids for the time being.”

“Really, Sina?”

“Yes. That’s an order from your future queen.”

Sanjing shook his head. “You’ll regret this.”

So much for “we.” What had Hesina expected? Sanjing was no Caiyan. If something didn’t go his way, he abandoned course. Weeks, months, years of his cold-shouldering reared in her mind, and with a bitter laugh, Hesina said, “One of us has to love Father and what he stood for. He believed in the people, he believed in the courts, he believed in truth, and he believed in the new era. I will too.”

A long silence passed between them.

“Fine.” The shadows fell from Sanjing’s face as he straightened. “I’ll go.”

The cowlick sweeping above his right brow was more prominent in the light. He was General Yan Sanjing, prodigy of the sword arts, master of strategy, commander of the Yan militias, but he was only sixteen, one year Hesina’s junior, and for a moment, her heart wavered. Perhaps she’d been too harsh—

“I hope ruling is everything you ever wanted.” He wielded his words like his sword: with precision, stabbing into her insecurities. “I hope this investigation is too.”

“Don’t worry.” She went to the door and held it open for her brother. She could walk any path, with company or without, as long as the justice her father deserved and defended waited at the end. “It will be.”

THREE

JUSTICE CANNOT BE BOUGHT.

ONE OF THE ELEVEN ON TRIALS

IT’S A LUXURY, PLAIN AND SIMPLE.

TWO OF THE ELEVEN ON TRIALS

The letters were stained along the edges. Hesina hadn’t noticed by candlelight. It was only when she’d stacked them all to the thickness of a pamphlet, and when the night drained out of the sky, that she saw the moss-green tint around the width.

The pages had been torn from a special edition of the Tenets. It was the only identifier she had, and the only one she wanted. Sanjing had planted a seed of suspicion, but she didn’t have to let it grow.

She pushed the letters away. Put them in a drawer. Opened the drawer and read them again, fingers drumming against the edge of her desk.

She summoned one of her pages. “Find whatever handwriting samples you can from members of the court,” she ordered. Damn Sanjing, and damn his paranoia. Damn the letter writer too. “Bring them to me along with a report on the officials with connections to Kendi’a. Any connections,” Hesina said firmly before the page could ask. How was she to know what might tantalize a person into betraying his own kingdom?

“Understood, dianxia. Will that be all?”

Hesina palmed her eyes. “That will be all.”

Once the page left, she put on her oldest dress, a plum-colored ruqun with an unraveling hem that wouldn’t mind being dragged through a few dungeon puddles.

* * *

Simplification had been the defining word of the Eleven’s reign. One and Two, the first co-rulers of the new era, had hacked away any relic excess they could. They pared down the complex written language invented by nobles to bar commoners from learning. They forbade tailors from spinning hanfu and ruqun from precious metals that could be used to fill coffers. They dissolved the imperial alchemy, dedicated to developing an elixir of immortality for the emperor. Monthlong festivals turned into weeklong festivals. Elite military sects were absorbed into the militia.

But the underground dungeon system remained an elaborate labyrinth of crypts, cells, and torture chambers. The relic emperors had filled them with rebel leaders and commoners. The Eleven had filled them with sooths.

Now most of the cells were empty. The handful of sooths who had escaped execution either lived like the Silver Iris or had scattered to the far reaches of the other three kingdoms. Only common criminals remained, such as the robber across from Hesina.

They sat in an old interrogation chamber, perfectly soundproofed for private conversations but aesthetically compromised by the bloodstains on the wall. The convict slumped in his chair, mute as a toad. His head was cast down, a shock of brown hair curtained over his eyes, making it hard to tell what he was feeling or thinking—or if he was even breathing. At least, in this way, Hesina couldn’t see his bruises and lament over the terrible first impression she’d made.

Nothing had gone as planned. Convicts weren’t allowed personal possessions, and the gnarled, crooked rod discovered in the robber’s cell apparently qualified as such. Hesina had stopped the guards from crushing it under their boots, but she’d been too late to spare the robber from their fists. Now she placed the rod on the table between them. She hoped—yet doubted—the peace offering would be enough.

The convict took the rod without a word.

Hesina cleared her throat. “Forgive me.” She hedged on the side of sounding overly formal. She didn’t want her emotions to betray her as they had in front of the Silver Iris. “I know this is all very”—strange—“sudden.”

Silence.

“You must have many questions.”

Evidently not.

With a breath, Hesina began to explain the circumstances of her father’s death. The words came slowly, then fast, tearing out of her as if they, too, were trying to outrun that day in the gardens.

She finished by describing the golden poison. Her chest heaved for air.

“As you can tell, the king didn’t die a natural death, contrary to what the decrees…” Did convicts look at decrees? “What the rest of the kingdom knows. Once I open an investigation, the Bureau will see the truth in the evidence. When they forward the case to the court, I’ll need a representative, and”—how long could she beat around the bush?—“well, when that time comes, would you be willing? To be that representative?”

Silence upon silence upon silence.

Hesina’s hands went clammy. She took inventory of other things, like the color of the convict’s hair. It was a brown like clay, at least three shades lighter than the lamp-black fuzz Yan babies were born with.

Maybe he wasn’t Yan. Maybe he couldn’t understand a thing she’d said. It wouldn’t be the first wrench in her plans, but it’d be the most unfortunate. How was she to make him appear like an examinee hopeful if he wasn’t literate?

“Excuse me.” Hesina whispered, as if he were dozing and she didn’t want to wake him. “You do understand the language, don’t y—”

Her breath hitched as his gaze snapped up.

Beneath all the swelling and discoloration, the robber was surprisingly young. His eyes, like his hair, were oddly pigmented, gray as stone, impenetrable as they captured hers.

Without warning, he took her right hand. She almost yelped as he pressed a finger to her palm and drew out the shaky characters of the common tongue.

I AM A LOWLY MERCHANT ROBBER. I CAN’T HELP YOU.

This was a start. “I’ll support you in any way that I can.”

WHY ME?

WHY SEARCH?

WHY THE ROD?

His grasp tightened as her hand closed. Cocking his head to the side, he examined her. He tapped on her knuckles, and after fighting to pace her racing heart, Hesina reluctantly uncurled her fingers.

YOU CAN’T SAY.

The writing stopped, then continued.

HOW WILL YOU TRUST ME WHEN YOU DON’T TRUST YOURSELF?

Gone were the uneven strokes and crude lines of someone unfamiliar with the language.

He was one to speak of trustworthiness. “Honesty on matters of the trial is all I ask for,” Hesina said with confidence she didn’t feel. Could he see the secrets she held under her tongue? Or had the lies stained her teeth?

AND IF I REFUSE TO BE YOUR REPRESENTATIVE?

“Then you refuse.” Her stomach dropped when she imagined the scenario—having courted treason all night only to walk away empty-handed. “You have that right.”

A PERSON OF PRINCIPLE.

WHO LIES FOR THE TRUTH.

Hesina held his impassive gaze. Well? she thought as the seconds passed and it became clear that he’d seen her for who she truly was. Her father had taught her honesty, but deception had been her first language. Well? Can you work with a hypocrite?

He drew the characters slower this time, as if he was making up his mind. He lifted his finger, and Hesina hardly dared to breathe. She looked down, even though the words were invisible, and searched for an answer in the tingles of his touch.

DO YOU KNOW HOW TO DUEL?

* * *

“A duel?” asked Caiyan after Hesina recounted her conversation with the convict.

It was the next day. After morning court, they’d met in the king’s study, sitting around a zitan game table on squat, jade stools carved to resemble napa cabbage heads.

“Yes, a duel.” Hesina considered the pieces on the ivory xiangqi board. “He said he’d only represent me if I won.”

“He’s mocking you,” concluded Lilian. “Or flirting with you. Or both.”

“His motives are unclear,” rephrased Caiyan. “But if he didn’t want to represent you, he wouldn’t have set terms at all. What do you think, milady?”

Think before you act, Hesina’s tutors always said. They made it sound so easy. In reality, Hesina acted more often than she thought, and her cheeks warmed as she recalled the course of their conversation. “He seems honest enough.” And shady enough. “I think I can trust him to keep his word.” Though she didn’t even know if he could speak.

But the Silver Iris hadn’t lied about the rod, the one and only in the entire dungeons. And the convict was clearly more than the merchant robber the prison documents claimed he was. Hesina remembered the strokes of his finger. The flush on her face extended to her neck. She quickly pushed her chariot three squares over, lining it up with another and entrapping Caiyan’s emperor.

“I’m still peeved that you met him without me.” Lilian’s voice rose from the daybed, where she lay on her back, an ankle propped on one knee and a cat’s cradle made of hair ribbon webbed between her fingers. Cyan and ochre blotched her apron. It’d been a dyeing day at the workshops.

“With any luck, you’ll see him in court,” said Hesina.

“Rod and all?”

“Please,” said Caiyan as he blocked the course of Hesina’s chariot with a black-powder keg, simultaneously endangering her steed. “It’s barely midday.”

Lilian snorted. “Says the reader of erotica.”

Caiyan sighed, but Hesina thought she caught a glimmer of a smile in his dark eyes. With a tug of jealousy, she looked back to the game board. Bickering was never so simple between herself and Sanjing.

“I’d recommend brushing up on your swordsmanship if you’re going to duel, milady.”

“You’d recommend?” Lilian hooted with laughter. “At least Na-Na can use a sword.”

“That’s debatable,” reminded Hesina. She was a flapping yuanyang duck next to Sanjing’s hawkish skill with the sword. But Lilian had a point. Hesina had never witnessed Caiyan holding a weapon, and she’d seen him injured only once. It wasn’t a memory she wanted to revisit.

With her double chariot formation foiled, Hesina resorted to the black-powder keg reserved for protecting her own emperor.

Caiyan advanced a foot soldier. “There’s a hole in your plans, milady.”

Hesina half-heartedly defended her emperor with a chancellor. “Do tell.”

Caiyan’s foot soldier crossed the river running down the middle of the board and was promoted. “Let’s say a trial is declared after the Investigation Bureau reviews the evidence and narrows down the suspects. You win the duel, and the convict agrees to be your representative. How will you convince Xia Zhong to pick him for you?”

“That’s easy.” Lilian fluttered a hand. “Spout something convincing from the Tenets. Passage 1.1.1. ‘A minister must serve!’ Passage 1.1.2. ‘A queen must have a convict with a rod as her representative!’”

Caiyan shook his head at Lilian’s impersonation while Hesina suppressed a giggle. Xia Zhong did, in fact, interpret the Eleven’s teachings of asceticism to the literal extreme. Word in the palace was that his roof was leaking; there were more mice droppings in his rice bags than rice; he slept on a praying mat, kept only one brazier running in the winter, and had been wearing the same underwear for ten years. For the minister’s sake, Hesina hoped the last one wasn’t true.

“I’ll think of a way,” she said to Caiyan. Hopefully soon.

“You won’t be able to bribe him.”

Even a monk had to want something.

“Sure,” said Lilian when Hesina voiced as much. “He’d probably ascend if you brought him the original Tenets.”

He wouldn’t be the only one. Scholars all over Yan would worship Hesina if she recovered the version penned by the Eleven themselves. It had disappeared shortly after the fall of the relic reign, and Hesina was as likely to find it as she was to find the mythical Baolin Isles.

Caiyan won the game, and Hesina rubbed her temples. “Only the Tenets?”

“I mean, it’s Xia Zhong.” Lilian flung away the cat’s cradle and stretched out on the daybed. “Elevens. I could never live like that.”

Yet she had. The twins didn’t share much about their past, but Hesina saw its fingerprints whenever Lilian took up the warmest spot in any room, and whenever Caiyan filled his empty rice bowl with tea and drank down the last grains. They lived life as if they might lose its comforts someday, as if they remembered what it was like to be without shelter, food, and father.

But Hesina wasn’t like the twins. Losing her father wasn’t like returning to a world she’d once known. She’d been unprepared.

She was alone.

Slowly, she pushed away from the square zitan table. She climbed a short set of stairs to the floor-to-ceiling windows lining the study’s upper half.

The sweet smell of overripe peaches rose from the imperial gardens below. Each palace followed the same layout: courtyards placed within courtyards, halls nested within halls. Her father’s study was the exception to the standard sprawl. Half of it rested atop an outcrop of granite, giving Hesina her favorite views of the four gardens—koi, silk, rock, fruit—and their respective ponds, connected by covered galleries zigzagging between mountain formations and thickets of jujube trees.

Hesina’s chest locked. Had her father looked out these windows eight days ago as she was looking now? Had the smell of summer peaches lured him to the gardens through the secret passageway behind the shelves? He had left his favorite tortoiseshell chair askew, his wolf-hair brushes dipped in ink. Abandoned on his desk, scattered and waiting, were a three-legged bronze goblet, a snuff bottle, a copy of the Tenets, left open to One of the Eleven’s biography. Hesina had agonized over whether to leave them be or accept that her father was never coming back.

In the end, she’d taken everything on the desk, along with the courier costume he’d been wearing at the time of his death, and boxed them away. Boxed away her grief too. Placed it out of dust’s reach, where it would remain like new.

“Na-Na…” An arm wrapped around her shoulders, and Hesina let Lilian pull her in. “You can always slow down. Rely on us. We’re here for you.”

It wasn’t the same. Her father had filled her nights with shadow puppets, dress-up, and maps of secret passageways. Year after year, he boosted her onto his shoulders—her very own throne—and together they’d watch the queen’s carriage fade into the mist, whisking her back to the sanatorium in the Ouyang Mountains, where the air and altitude could preserve her failing health. Afterward, the king would take Hesina into the persimmon groves. They’d eat fruit picked straight off the branches until they bloated, and Hesina would cry, missing a mother who would never miss her.

Her tears had blinded her to the unconditional love right in front of her. Now, justice was her only way to say thank you. To say goodbye. To say I love you too.

Caiyan joined them on the second level. He placed a hand on each of their shoulders, and the three stayed that way until a distant drumbeat passed through the air. Horns blared into the chorus, and a gong struck a single, deafening note.

The twins stepped back at the same time Hesina pulled away.

She walked out of the study, telling herself not to run, not to rush. Only fools were eager to receive disappointment. But the sound of the gong resurrected the little girl she had been, and she became a fool again as she climbed the steps of the eastern watchtower, first at a steady pace, then a jog, then a run.

She burst through the doors, cut through the startled guards, and leaned over the granite parapet. The watchtower stood a whole li from the city walls, but Hesina was tall enough now to see the line of carriages on her own. It slithered through the Eastern Gate like a serpent scaled in mourning white, horned with banners flying the imperial insignia, wending between crowds of commoners.

Hesina’s heart filled and emptied all at once. Her mother had finally come home.

FOUR

THERE SHOULD BE SIX, ONE FOR EACH MINISTRY, GRANTED OFFICE ON THE BASIS OF MERIT.

ONE OF THE ELEVEN ON MINISTERS

THEY’RE THE LAST LINE OF DEFENSE AGAINST CORRUPTION.

TWO OF THE ELEVEN ON MINISTERS

Standing on the terraces, with commoners and nobles blanketing the Peony Pavilion below, Hesina couldn’t remember the warmth of her father’s study. Blades hung in the air as her mother made the slow ascent up the terraces, the people rippling as they bowed. Summer had ended with the return of the queen, and autumn, the season of death, began.