5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

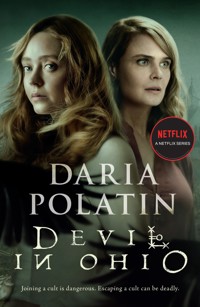

Joining a cult is dangerous. Escaping a cult can be deadly. When fifteen-year-old Jules Mathis comes home from school to find a strange girl sitting in her kitchen, her psychiatrist mother reveals that Mae is one of her patients at the hospital and will be staying with their family for a few days. But soon Mae is wearing Jules's clothes, sleeping in her bedroom, edging her out of her position on the school paper, and flirting with Jules's crush. And Mae has no intention of leaving. Then things get weird: Jules discovers that Mae is a survivor of the strange cult that's embedded in a nearby town. And the cult will stop at nothing to get Mae back.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

SWIFT PRESS

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2022

Originally published in the United States of America in 2017 by Feiwel and Friends, an imprint of Macmillan Publishing, LLC

Copyright © Daria Polatin 2017

The right of Daria Polatin to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Book design by Rebecca Syracuse

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800751378 eISBN: 9781800751385

To those who have been hurt, and come through the other side even stronger.

To my mother and sister, for everything.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This book is based on a true story. Not my story, but someone’s. What matters is that most of it actually happened.

Just be glad it didn’t happen to you.

PROLOGUE

AS SHE PEELED THE CATATONIC GIRL´S HOSPITAL GOWN off her back, the nurse’s face paled: red lines, brimming with blood, had been carved deep into the teenage girl’s porcelain skin. The congealed liquid was starting to tighten, crack. The maroon lines were precise, stick-straight. There was no way the girl could have done this herself.

This had been done to her.

The nurse gazed at the nest of lines. The slices formed a five-pointed star. An upside-down one. Around that, a circle was engraved.

Sign of Satan.

Slowly—carefully—the nurse replaced the thin cotton gown. With an unsteady hand she pulled out her cell, stepping backward across the linoleum as if repelled from the girl’s damaged body. Cell phones weren’t normally permitted for use on the hospital floor, but this seemed like an emergency.

When the person on the other end of the line answered, the nurse whispered fiercely—

“You better come quick.”

PART ONE

The world breaks every one

and afterward many are strong at the broken places.

—Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms

CHAPTER 1

THE TAN CORNFLAKE LOOKED LIKE A LONELY ISLAND in the translucent sea of 2 percent milk. As I watched it drift across the screen from behind my phone, I wondered why, as soggy as the flakes got, they never seemed to sink.

My phone wasn’t great with close-ups, which was why I needed a new, real camera, but I could sharpen the shot in a filter—if I could just get the framing right.

“No phones at the table,” my little sister, Danielle, reminded me from over her own bowl of cereal. She was eleven, and a tattletale. She was also right—our mom didn’t like us to talk, text, or snap pics at the table, but this shot was lining up so perfectly.

CLICK—

I rebelled against the world in my own small way.

(It’s) Still Life was what I was calling the series. It was a collection I was putting together for my application to a digital photography program at the Art Institute of Chicago next summer. I wanted to magnify the everyday moments we took for granted, examine what we dismissed as mundane.

Dani’s eyes narrowed. I didn’t want to grant her a win, but it was too early to fight. I slipped my phone back into the pocket of the vintage corduroy pants I’d scored at Goodwill and stared, daring her to tell Mom.

Dani turned back to flipping through her InStyle magazine without further confrontation.

“I’ll be there as soon as I can. Thanks, Connie.”

My mother had a weird look on her face as she ended the call. She was completely inept at hiding her feelings. It was a trait she had unfortunately passed down to me.

Having your face reveal exactly what you’re feeling is an extremely unhelpful characteristic, especially as a fifteen-year-old. I had paid dearly for this feature in awkward situations of yesteryear—the time I let my face show that Lucas O’Donnell already having a date to the eighth-grade graduation dance was heartbreaking; or that my neighbor Stacy Pickman did look fat in those jeans. But the worst was the time I was standing outside the gym last fall with my best friend, Isaac Kim, when I inadvertently let my jaw drop hearing Larissa Delibero describe the blow job she’d given Eric Mann. In great detail. Larissa caught my stunned look and commented, “Obviously someone’s never given a BJ.” Her pack of cheerleaders laughed, egging her on. “Might wanna check out some porn before you get a boyfriend. If you ever get a boyfriend.”

Larissa was correct: I had never given a BJ. Sure, I had kissed a few boys, but I hadn’t ventured much beyond that. The thing was, I wasn’t even sure I wanted to anytime soon.

“Jules,” Isaac had whispered, “you need to get that face under control.”

That night I had started practicing not showing every ounce of what I was feeling on my face. Each night, I stood in front of the mirror, thinking about happy things, sad things, upsetting things, all the while keeping my face in neutral. Since then I was better at it. Admittedly still not great, but at least not as bad as Mom. Baby steps.

“What’s the matter?” my older sister, Helen, asked my mother, entering the kitchen, texting. She was sporting a tweed jacket and skirt, which was a little matchy-matchy for my taste, but it worked perfectly on her. She had inherited my mom’s tall, slender frame, so everything looked good on her. She also had Mom’s straight auburn hair. I had our family’s signature auburn locks too, but unfortunately my hair had a hard time making up its mind if it identified as straight (like Helen’s) or curly (like Dani’s), so it occupied a frizz-filled middle ground no amount of product seemed to be able to tame.

Not taking her eyes off her phone, Helen plopped her book bag down on the kitchen table, sloshing my cereal so hard that it nearly spilled over onto my sleeve.

“Hey,” I protested, but Helen ignored me, laughing at something on her screen. Ignoring me was pretty much Helen’s M.O.—at home and at school. She was an effortlessly smart senior, kept a 4.0 while also being captain of the field hockey team, and was queen of her clique. My hours of homework yielded Bs—plusses if I was lucky—and I barely got to play at my volleyball games. And while I wasn’t exactly unpopular, I wasn’t setting any records for social status either. Sure, I had Isaac, who was a great best friend, and a few girls I knew from volleyball. I’d tried to be better friends with other girls in the past, but for some reason it never seemed to work—I always said the wrong thing or didn’t say enough. I’d secretly hoped that the jump from middle school to high school would magically catapult me into the next level.

Spoiler alert: it didn’t.

Lately I’d been trying to convince myself that the fact that no one paid attention to me was actually a good thing. It meant I could blend in, take my photographs without being noticed, watch the world from the safety of my screen. High school was just something I had to get through. It was okay that I didn’t seem to fit in now. I’d do better later, in college—in Life. Then one day I’d be a successful photographer in New York City or San Francisco, and no one would remember that in her high school days, world-famous editorial photojournalist Jules Mathis hadn’t exactly fit in.

Or at least that’s what I was telling myself.

“Is something going on at work?” Helen reached for the French press of coffee that Mom had brewed for Dad. Drinking coffee was something I’d wanted to try—it seemed grown-up, more sophisticated than drinking soda or juice—but I couldn’t get past the smell, which to me was like chocolaty dirt.

“Nothing’s wrong,” Mom practically sang, forcing a smile.

I took a bite of my soggy cornflakes and glanced at Dani, hoping she’d acknowledge Mom’s obvious evasion of the truth, but she was consumed with her glossy magazine. This past summer Dani had lost a bunch of weight and had become obsessed with reading about celebrities.

“What’s wrong, honey?”

My dad arrived through the swinging kitchen door and saw Mom’s Everything’s Fine face.

“Everything’s fine, Peter.” Mom smiled, not looking him in the eye.

“Liar,” he wagered, kissing her on the cheek. Mom didn’t respond. She just reached into the cabinet for a box of tea, proving my dad right. My parents were high school sweethearts and knew each other better than they knew themselves. True love? Kind of creepy? I could never decide.

“I have to go in to work early,” she explained, plunking a bag of Earl Grey into her travel mug of hot water. “You mind dropping off the girls?”

Mom hadn’t bothered to ask Helen to take us, even though Helen and I went to the same school, and Danielle’s middle school was right across the street.

“Sure thing,” Dad said, reaching for the French press before he realized it was nearly empty. “Where’d all my coffee go?”

DING! Helen’s phone sounded—probably her boyfriend, Landon, texting that he was waiting outside to chauffeur her to school.

“Thanks, Daddy!” Helen flashed a grin and zipped out the door with a smug smile, her streak of perfection unbroken.

Mom capped her travel mug and skipped her scrambled eggs in favor of her work files, stuffing them into her bag. “Pizza okay for dinner?”

“I’ll just have salad,” Dani said, eyeing a too-thin model in her fashion bible.

“Danielle, you can eat a slice of pizza,” my mom encouraged. Mom was a psychiatrist and had covertly coached Dani through the change in physique. My guess was Mom had seen her share of eating disorders at the hospital where she worked.

“Okay,” Dani gave in. “With pepperoni.”

“No mushrooms,” I requested—I just couldn’t get over their texture.

“You got it,” Mom assured me, hurrying out of the kitchen. “Have a good day, everyone!”

She’d forgotten her travel mug of tea. It was unlike my mom to leave in such a rush. Whatever call she’d gotten from work must have been important.

“Can we run through my sixteen bars for my audition one more time?” Dani asked Dad.

“I don’t want you and Jules to be late, sweetheart,” he countered.

“Please? You’re so good at playing the piaaa-nooo?” she belted. “It’ll take two sehhh-connnnds?” Dani could get a homeless guy to give her money if she asked the right way.

“Okie-doke. Just one time through,” Dad caved as he followed her out.

I was left alone in the kitchen. This seemed to happen a lot in my family, everything kind of swirling around me. Me ending up alone.

As the upbeat strains of “Defying Gravity” from Wicked floated in, I experimented with a few filters on the photo I’d taken of my unsunk cereal before posting it on Instagram. I liked posting images that told stories—a forgotten mitten on a playground, a couple holding hands, a kid staring at the cookie aisle. I loved the way photos let you express something without having to actually say anything.

I captioned the photo #unsinkable, along with #julespix #(its) stilllife #picoftheday, and posted it.

A “like” immediately popped up, causing my stomach to flutter. Someone had noticed me.

I checked to see who had liked the photo.

ig: futurejustice

My face fell. It was from Isaac. While I appreciated the “like,” somehow it didn’t make me feel as special knowing that it came from him. And just like that, I went back to being average again.

CHAPTER 2

THE TEENAGE GIRL´S THIN FRAME LAY ON THE hospital bed, her sleep anything but restful. Her small lungs lifted upward with a short, jagged gasp for air as her sedated body struggled to keep itself oxygenated.

It had been a long night for the girl—ambulance, EMTs, ER doctors. She’d landed in the trauma unit, where the staff worked to stem the bleeding from the wounds on her back. The police had been there too, trying to find out what they could about the incident, but the girl was so depleted she could barely speak, and when the police ran her description through a missing persons database, they came up empty. They hoped that a social worker from Child Protective Services might be able to obtain more information.

And they needed it.

The girl had fiery rope marks on her wrists, ankles, and the back of her neck, telling the tale of forcible restraint. What was even more disturbing, though, were the extensive bruises that covered her body. Purple and blue swirls of blood circled just under her skin’s surface like weather patterns of hurt.

The hushed conversation around the hospital had surged during the morning shift change: Who was this strange girl who’d been found by the side of the road with the sign of Satan carved into her back? And more important, what had happened to her?

The girl expelled a labored breath, her rib cage sinking back toward the bed.

“How ya doin’, sweetie?”

Connie—a veteran nurse who lived for her patients—shuffled in, tired from being up all night. Although she was supposed to have left the hospital hours ago after her night shift, she had traded shifts with a colleague so that she could stay near the new arrival and make sure she was okay. The girl didn’t stir.

Stepping over to the bedside, Connie checked the patient’s chart. She adjusted the girl’s IV of antibiotics. Although the girl’s pitch-black strands of hair were still caked with mud, they managed to keep their raven luster, even under the hospital fluorescents. Her milk-white skin had been wiped clean, although a few specks of dirt still spotted her cheeks.

Connie leaned over, stretching her stout frame across the sleeping girl to get a glimpse at her back. Despite the white bandages that had been placed over the girl’s wounds, blood had seeped through the barricades and now painted the thin hospital gown. She’d have to change the dressing after she checked her vitals.

Connie placed a gloved hand on the girl’s shoulder. The girl’s eyelids flickered, then slowly separated.

“Open for me?” Connie held a thermometer near the girl’s mouth to check her temperature. The girl let the nurse get a reading.

“Have to make sure you don’t get a fever. Last thing you need is an infection,” Connie warned. She checked the thermometer. “A perfect 98.6! Good girl. You hungry, sweetie?”

The girl’s thick lashes swept up toward Connie. Weary with sedatives, she shook her heavy head no. She sank her ear back down onto the pillow, her eyes fluttering closed.

Connie decided not to fight it and let the girl drift back to sleep.

“I’m here, Connie!” Dr. Suzanne Mathis raced through the doorway. “Got here as fast as I could,” she explained, pulling her white hospital coat around her. “Is this—”

Suzanne’s gaze fell on the sleeping girl. As her eyes took in the blood-spotted gown, the waifish body, the bruises, her expression clouded over.

“She’s about Julia’s age, right?” Connie asked Suzanne.

Suzanne nodded, but her face paled at the thought of her daughter Jules being compared with this injured girl.

“Are her vitals stable?” Suzanne asked, stepping toward the bed.

“They are, but she’s been mostly nonresponsive. Poor thing’s been through a lot.”

Suzanne perused her chart. “Do we know her actual name?”

“Came in with no identification so it’s ‘Lauren Trauma’ till we know more.”

“The police couldn’t figure out anything more?” It was unusual for someone to arrive with absolutely no identifying factors.

Connie shook her head. “Not yet. This one’s a mystery.”

“How’s her back?” Suzanne asked, noting the blood-speckled bandages.

“It’s—” Connie started, but wasn’t sure how to finish. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” she concluded.

The girl’s chest rose and sank, rose and sank. The two women watched their patient, mesmerized by her mysterious arrival and clearly traumatic past.

“She’s like a broken angel,” Connie sighed.

Suzanne finally tore away her stare. “I’m going to get some tea. Page me when she wakes up?”

Connie nodded. “Will do.”

Suzanne took one more look at the patient’s sleeping face. She watched as the girl’s eyelids twitched.

What nightmares lay behind those lids?

CHAPTER 3

THE CRISP AUTUMN LEAVES CRUNCHED UNDER MY SECONDHAND oxfords. They were a little more formal than the Converse I’d sported last year, to go with my recently adopted vintage look. The heels made a satisfying click against the pavement.

As I headed down the sidewalk toward school, I braced myself for Monday morning. Everyone would be talking about how much fun they’d had over the weekend—what parties they’d gone to, who got wasted, who hooked up with who. Friday night I’d Netflix-binged on British comedies with Isaac—one of the only things he and I could agree on to watch. He was a big documentary fan, and I’d recently gotten into old movies. There was something about them that I found comforting. I’d also stayed in on Saturday night, theoretically to babysit Dani while my parents had their date night, but really to rewatch Casablanca.

“You again.” I heard a voice coming from a yellow school bus. Isaac peered down at me through the rectangular slat of an open window.

“Come on, Rapunzel,” I returned. Isaac flicked his chin-length black hair out of his eyes. He was in perpetual need of a haircut.

“Ugh, fine, I guess I’ll continue to spend nearly every waking moment with you,” he conceded, hopping down the steep steps of the vehicle.

“Who else would you hang out with?” I asked, adjusting the straps of the new tan book bag Mom had gotten me at a Labor Day sale last week. I liked its brass buckle and thick stitching, but the faux-leather straps were already starting to fray. No wonder it was on sale.

“Who else would you hang out with?” Isaac countered. Fair point.

As Isaac and I turned up the lawn-lined walkway toward the two-story redbrick building, our steps fell in sync. We’d been best friends since third grade, when he moved from Alaska to Ohio to live with his aunt. I never asked too many questions about why, but it seemed like whatever had happened to Isaac earlier in his life had made him the kind of person to make room for himself wherever he went.

“True or false,” Isaac started. “In the United States, campaigns that support candidates for public office ought to be financed exclusively by public funds.”

“Do we have a quiz?”

“Wrong answer. It’s my next topic.” Isaac was super into Speech and Debate, and had competed on a team since middle school.

“Do I even need to ask which side you’re arguing?” Isaac was always fighting for the underdog. He was a perpetual man of the people.

“Campaigns should be fought fair and square, with the same budgets on both sides. It’s not an impartial selection process if one side gets unlimited private funding and the other doesn’t. Additionally, it’s absurd the amount of money that’s spent, period. Why not put that money to better use? Like toward infrastructure, or public resources?”

“Sounds like a good argument,” I assured him.

“I’m going up against Victoria Liu, who is vehemently pro– corporate financing. Like, hello, Citizens United is ridiculous,” he argued. “But her dad’s a big anti-union guy, which around here is obviously blasphemy, but it figures she’d take that position. Blech. And I know she’s gonna try to play hardball with me—she’s still mad since I whipped her ass at regionals.”

“You guys are on the same team. It’s only September; you have a whole year to get through with her.”

“I still did way better than her,” he smirked, not hiding his ambitious nature. “And don’t think I’m just being competitive with her because we’re both Asian,” he added.

I smiled. “I think you’ll kill it.”

“I know I will,” he replied with unironic certainty. “You should join the team, Jules.”

“Yeah right, you know how much I love public speaking,” I joked.

“You need to bump up your extracurrics.”

“I’m still waiting to hear from the Regal.”

I had finally convinced myself to submit an application to take pictures for our weekly school paper. They already had an excellent photographer on staff, though—a senior named Rachel Robideaux—so it was unlikely they’d need anyone new. But, channeling the boldness of Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, I was trying new things.

I did really want to be a photojournalist. But, full disclosure, I might have had a second reason for wanting to join the paper. And that second reason might have been named Sebastian Jones.

Sebastian was also a sophomore now, and had shown up at school last fall. He’d moved here from Philadelphia and immediately made his mark, scoring the highest GPA in our class. He’d written a Remingham Regal article on “The Fifteen-Minute Hack to Improve Your GPA,” quickly becoming one of their star journalists, and at the end of the school year he’d been named editor in chief—the youngest in the school’s history.

We’d ended up as lab partners last year in Earth Science. His friendly demeanor made him really easy to talk to, which somehow calmed my jittery nerves. As we put together our final project, on plate tectonics, Sebastian had confided in me that he planned to restructure the school paper—and bring in some fresh blood. As far as I knew they hadn’t offered any positions yet, so I was still holding my breath.

“They’d be idiots not to take you,” Isaac assessed. “You’re just as good as Rachel Robideaux, if not better.”

“You might be just a little biased,” I smiled. Secretly, I loved that Isaac’s faith in me was as strong as his faith in himself.

“Oh!” Isaac erupted. “This weekend there’s a screening of a documentary on America’s surveillance state. We’re going.”

“Only if you do a David Lean double feature at the Independent with me. Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago in seventy millimeter.”

“Are they in black and white?” Isaac whined.

“You liked the Hitchcock films,” I countered.

“Because those were creepy.”

“These are classics. And in color.”

“Fine, as long as you buy me popcorn and a drink,” he negotiated. “Deal?”

But I had stopped listening. Across the swarms of students I had caught a glimpse of something—okay, someone. Sebastian was standing on the side entrance ramp, scrolling through his phone. The newspaper office was near the side doors, and although there was usually a contingency of Goth kids perched on the railing smoking, the ramp was also frequented by a Regal staffer or two. I’d seen Sebastian a few times since school had started, and we’d caught up about our summers—he’d been away at a journalism camp like an exciting person while I lifeguarded at the local pool like a boring person. But seeing him in person still made my breath catch in my chest.

“Earth to the Friend Formerly Known As Best.” Isaac called back my attention.

I willfully tore my thoughts away from Sebastian. “What? Yeah, I’ll get the tickets,” I said, trying to cover the fact that I’d spaced.

Isaac folded his arms. He could tell I hadn’t been listening, and not listening was a federal offense in his book.

“Where is he?” Isaac searched the crowd.

“Who?” I tried to play it off, but I knew who he was talking about and he knew that I knew.

“It’s written all over your face,” he retorted.

Damn. “Whatever. He doesn’t even like me.”

“You two just need to bang and get it over with,” Isaac teased.

“Yeah, I’ll get right on that. As soon as I can string together a sentence in front of him.”

The truth was, Isaac and me discussing banging was as arbitrary as us talking about sailing yachts, living in the landlocked middle of Ohio. Neither of us had any real experience. I’d only been to first base a few times, and Isaac was practically asexual. He never talked about liking girls—or boys, for that matter. Sometimes I wondered if Isaac might come out as bi or gay, but he never brought it up, so neither did I.

“Hey, what should we do for the Social Studies presentation?” Isaac mused, changing the subject as we headed up the stairs toward the front entrance. He took the steps two at a time.

“Isaac, it’s not until November,” I reasoned.

“I know,” he defended. “I was thinking: The Power of the Proletariat in Cold War USSR. Fun, right?”

I cast one last glance at Sebastian. The morning light glinted off his black-rimmed glasses as he cracked a smile at something on his phone.

“Sure,” I replied as we stepped through the front doors of the school. “But then you have to promise to watch North by Northwest with me.”

“Again?” he sighed.

CHAPTER 4

DR. MATHIS: Testing, testing. Is this recording? I pressed the red dot. . . . Okay, looks like it’s working.

[Creaking of bedsprings.]

DR. MATHIS: Oh, you don’t have to get up, you can stay where you are. You had a long night.

[Shuffling of some papers.]

DR. MATHIS: So, I am Dr. Suzanne Mathis, attending psychiatrist at Remingham Regional Hospital, and I’m here to assess how you are doing. I am here with patient—

[No answer.]

DR. MATHIS: Would you mind telling me who you are? We don’t have any identification on file for you yet.

[No answer.]

DR. MATHIS: Your name? Or do you have some kind of ID that the staff might have overlooked?

[Leaning close] Please note that the patient has shaken her head, indicating that she has no ID.

That’s okay. Why don’t you have some water?

[After a short silence, a cup clinks.]

DR. MATHIS: I know you’ve been through something unspeakable. Something you never want to face again, let alone talk about. But I want you to know that I’m here to help you. That is my entire job. To help you work through what happened.

They’re calling you “Lauren Trauma.” That’s your code name in your file. We use it for your own protection, so that only people we give it to can find you. But can I tell you a secret? The ones who we never find out their real name—they’re forgotten, they’re the ones left behind. And we’re not going to let that happen to you.

[A tired, raspy teenage girl’s voice finally speaks.]

MAE: Mae. My name.

DR. MATHIS: Thank you for telling me, Mae. That’s a beautiful name. Do you spell it with a Y?

MAE: E.

DR. MATHIS: Wonderful. And your last name?

[No answer.]

DR. MATHIS: Okay. We’ll stick with Mae for now.

So Mae, tell me what you remember from last night. Besides the doctors and tests and all that. Tell me about what happened before you got here.

MAE: I—don’t remember anything.

DR. MATHIS: Nothing at all?

MAE: I remember—the truck driver. He found me. There were bright lights, and then he called the ambulance, I think.

DR. MATHIS: Thank you, that’s what I have here as well. He called the ambulance at 12:52 a.m. It is pretty incredible that he saw you. Police said you were lying nearly fifteen feet from the side of the highway. How did you land so far from the road?

MAE: I don’t know.

DR. MATHIS: Did you jump out of a moving vehicle? Or head into the woods from the road? Or did you maybe come from inside the woods?

MAE: I was in a car. Van. A white one.

DR. MATHIS: Okay, so you were riding in a van. In the passenger seat?

MAE: In the back. I was thrown from there.

DR. MATHIS: You were thrown from a moving vehicle?

MAE: Yes.

DR. MATHIS: By thrown, do you mean that the van hit a bump or something, or it got a flat tire?

MAE: No, by a person.

DR. MATHIS: You were thrown by a person out of the back of a van.

MAE: Maybe that’s why I rolled so far.

[Quiet. Some scribbling.]

MAE: It was two people.

DR. MATHIS: Two people threw you?

MAE: And someone else was driving.

DR. MATHIS: Do you know who threw you?

Do you remember who was driving the van? Or what he—or she—looked like?

MAE: I don’t remember. I’m very tired—

DR. MATHIS: Of course you are. Just a little bit longer. Do you remember anything about them? Any of the people involved? Were they tall, short, thin, heavy?

MAE: They were wearing black.

DR. MATHIS: Black sweaters? Jackets? Pants?

MAE: Long black coats.

DR. MATHIS: And what about their faces? Could you see what any of them looked like? Do you remember what color anyone’s hair was? Or—

MAE: They were wearing hoods.

DR. MATHIS: Hoods?

MAE: Black hoods.

[Pause.]

DR. MATHIS: Mae, where are you from?

MAE: From?

DR. MATHIS: Are you from Ohio? [Leaning in] Note that the patient has nodded affirmative. Where in Ohio are you from? Somewhere nearby?

[Quiet. A sip of water is gulped.]

DR. MATHIS: Mae, I’m going to help you. I’m going to help you stay safe, and help keep you away from whoever did this to you. It won’t be easy, but we’re going to have to trust each other. Can you do that? Can you trust me?

MAE: [Pause.] Okay.

DR. MATHIS: Good, thank you. I’ll trust you too. Okay, this next part might be difficult, but we’re going to get through it. Together. Mae, who did this to you? The carving on your back. Who cut you? Was it someone you knew?

[Leaning close] Please note that the patient is nodding her head yes. Can you tell me who it was? The more I know, the more I can help you. Was it someone from your family?

You’re nodding yes.

MAE: Mmm-hmm.

DR. MATHIS: Was it your—father?

[No answer.]

DR. MATHIS: Mae, most abuse happens from within the family. It’s nothing to be ashamed of, because none of it is your fault. Do you understand that? None of it is your fault.

Was it your dad, or an uncle?

MAE: Yes.

DR. MATHIS: Which one was it?

[After a long pause.]

MAE: Both.

[Quiet.]

MAE: I need to rest now—

DR. MATHIS: Are you sure you don’t want to tell me—

MAE: I’m so tired.

DR. MATHIS: [Leaning into the microphone] Note that the patient has closed her eyes and is no longer responsive.

CHAPTER 5

CLICK.

A crumpled chip bag lay on the puke-colored linoleum a few lockers over from mine. Its silver interior sparkled under the hallway fluorescents. Inspecting the frames I’d snapped, I sharpened the image and bumped up the green highlights, then posted the picture to Instagram, captioning it #trashcan’t.

The pic would be a good addition to my portfolio. The summer program application wasn’t due until January, but I wanted to get a head start and send my submission in early. The idea of focusing on photography for a whole month sounded like heaven.

At first, Mom had been worried about the idea of me spending four weeks in a big city, but since she went to a yearly convention in Chicago in December for work, I’d convinced her to take me with her. That way I could show her how well I could manage. Then she’d have to let me go.

My stomach groaned, reminding me that I had turned my nose up at the mystery meat on offer at lunch and was starving, so I made my way down the hallway to the cafeteria. When I reached the vending machines, the choices stared back at me, daring me to make a selection. Sometimes, when I got too hungry, deciding what to eat felt like brain surgery.

“Go with the granola bar,” I heard from behind me.

I turned to see Sebastian adjusting his glasses. Feeling a blush blooming across my cheeks, I quickly swiveled my attention back to the prepackaged foods.

“But the peanut butter–filled pretzels are hard to beat,” I replied, hoping I didn’t sound as nervous as I felt. I punched in D6 and a snack plunked to the bottom of the machine. Before I realized what was happening, Sebastian knelt down and retrieved the plastic pack.

“Gracias,” I managed.

“De nada,” he returned, handing the bag of pretzels to me. I’d forgotten how easy it was to talk to him.

I ripped open the packet and held it out to him. He reached in and popped a protein-filled pretzel into his mouth. I took one too.

“Oh wow,” he said through crunches. “Good call, Mathis.” The side of his mouth rose into a half smile. I could feel myself staring at his lips, making me feel kind of giddy and queasy, like I’d eaten too much candy.

Pull yourself together, Jules. He is only a human.

Sebastian reached into the pocket of his jeans and deposited a few quarters into the machine. “How’s your day going?”

“Despite forgetting the capital of Serbia in Social Studies, not too bad,” I answered.

“Belgrade,” he said without pause as he punched in his snack selection.

“Ding ding ding.”

A bag of peanut butter pretzels dropped. His choice was obviously a sign that he was in love with me and we were meant to be.

“I know what you’re thinking,” he said.

Oh no. Was it that obvious that I liked him? Had he caught me staring this morning?

“The Regal,” he said, tearing open his bag of carbs.

Right. The paper. Duh.

“So,” Sebastian started, “we’re not going to bring on a new staff photographer.”

My stomach sank. This was very not-good news.

“Rachel’s got it under control, and she’s a senior, so I want to give her, well, seniority,” he explained.

I felt the strap of my book bag slipping down my decades-old shirtsleeve, which I’d rummaged from my grandma Lydia’s old clothes in the attic.

“She’s a talented photographer,” I said, willing myself not to show my disappointment on my face.

“However, I’m starting a new section on the back page of the paper, and to go with it, there’s a new position I’m creating,” Sebastian revealed. “A portrait-a-week, Humans of New York–style column. Intimate, no-frills portraits of people around school, with short interviews accompanying. A little get-to-know-you type thing, with interesting facts about the subject.”

That sounded like a supercool idea, but I didn’t know what to say. My brain was sprinting to figure out where he was going with this.

“That sounds awesome,” I encouraged. “We see people around school every day, and we know who people are on a superficial level, but not what’s underneath. Why they are the way they are. Sorry, I’m rambling,” I apologized.

“Exactly! It’s about connecting with people you don’t know.”

“ ‘People You Don’t Know.’ That’s what you should call it,” I spitballed.

Sebastian cocked his head, his shaggy brown hair falling across his forehead. “I like the way you think, Mathis.”

“I like the way you think,” I returned. Oh God, I was so bad at this.

Luckily he didn’t seem to notice. “So the column might be something you’re up for? You’d take the photos and also do the interviews.”

I froze, willing myself to come up with a response. Sebastian continued, “You have such a great eye, Jules. Your images really tell a story.” He was looking right at me, his warm brown eyes staring into mine. “You’d be a perfect fit.”

“I’m in,” I blurted, trying to sound more confident than I felt.

“Excellent! Why don’t you come in after school tomorrow and interview with the rest of the team.”

“I’m there.” I beamed. Then corrected, “I mean, I’ll be there. Tomorrow. Not, like, now. You know what I mean.” Stop. Babbling.

“Can’t wait.” Sebastian popped a pretzel and headed down the hall.

Neutral face. Neutral face. Neutral face.

CHAPTER 6

“YOU HAVE NO RIGHT TO DO THIS!” the tall man shouted.

“Sir—” Dr. Mathis cautioned the imposing man in a tone one usually used on cornered animals about to attack. “Please don’t raise your voice at me.”

She was standing across from the man in the hospital lobby, the sliding doors shut against the crisp fall wind. There were a few waiting patients trying not to stare at the escalating dispute.

“Now listen, lady—” he snarled.

“Doctor,” Suzanne corrected, quickly deciding not to share the rest of her name with the man. He was wearing a long brown work coat, and a low-pulled cowboy hat covered most of his face. He had a menace to him that made you not want to ask what he did for a living.

“I don’t give a rat’s ass who you are,” he challenged, pacing closer to her. “I know she’s here. You have no right to deny me.”

His proximity forced Suzanne to take a step backward. She cast a quick glance at the few people watching. The receptionist behind the desk looked on, concerned.

Suzanne squared her shoulders and forced herself to face the man.

“We’re only allowed to release the patient’s information to listed next of kin. It’s hospital policy,” she said, trying to appeal to the man’s rational side, in case he had one.

He didn’t.

“Screw your policy!” he spat out, making little effort to control his fury. And although crimson from sun damage, his face grew even redder. “I’m takin’ her out of this place!”

“I’m afraid that’s not possible.” Suzanne stood a little straighter as he towered over her.

He leaned closer, his beady eyes only inches from Suzanne’s face. “Are ya? Afraid?”

Suzanne took a deep breath. She wasn’t going to take the bait.

“While I would like for you to have your needs met,” Suzanne said slowly, steadily, “we are not legally allowed to release her to you.”

“I’ve had enough of your lies. Lemme talk to someone who can actually do something,” he demanded, taking one last step toward Suzanne. Her back was now up against the reception center wall, making it impossible to move any farther away from him. The man had her trapped. She cast a glance toward the receptionist, who picked up her phone.

“Code purple,” the woman whispered into the receiver.

The man’s eyes remained focused on Suzanne, who stared back, boldly meeting his gaze. “She’s not medically cleared for discharge.”

With that, the man whipped his fist into the air, incredibly close to Suzanne’s face. He held it there.

The room tensed.

There was a long moment where neither Suzanne nor the man moved an inch.

Then he spread his hand open slowly, softly stroking Suzanne’s cheek.

Suzanne flinched but kept still as she could as the man’s rough hand moved across her face. She could barely breathe.

“You’re just a scared little lamb, aren’t you,” he taunted.

“Dr. Mathis!” A security guard hurried into the lobby. His entrance caused the tall man to step back from Suzanne, breaking the spell that had fallen over the room.

“Sorry, I was helping Mrs. Engle out to her nephew’s car,” the hefty security guard explained. “What’s going on here?”

“It’s okay, Jerry,” Suzanne said, pulling her white lab coat around her waist, regaining her composure.

“We have some trouble?” Jerry asked the man.

“Nah, we’re just gettin’ to know each other,” the man said with a wry smile.

Jerry wasn’t as tall as the cowboy hat–wearing man, but he did have a handgun tucked snugly into his belt.

“Why don’t we step outside, sir.” Jerry was clearly not just asking.

Two cops suddenly appeared. “This the code purple?” one of them asked, reaching for his gun.

The tall visitor raised his hands in compliance. “Calm your horses, I’m leavin’,” he growled. He stepped toward the lobby doors, then turned back and flashed his dark eyes at Suzanne.

“I’ll be back for the girl. You can’t keep her forever.”

CHAPTER 7

JUST WHEN I THOUGHT I´D GOTTEN A LEG up in the being-noticed department—Sebastian had thought of me to write and photograph the new column!—I was immediately forgotten again.

Mom hadn’t arrived to pick me up at school, and because of volleyball practice I’d already missed the late bus. I’d texted and even called her, but she didn’t answer, which was weird, ’cause she always answered, even if it was a busy right now call you back text.

I’d texted Dad too, but I knew that was useless. He was terrible with all things phone-related, and I was sure he was working anyway.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)