Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

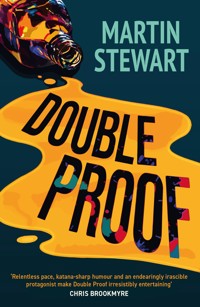

Stolen whisky, drug dealers, bent cops, social influencers and yakuza mobsters. And Robbie Gould is caught in the middle. 1964. A hoard of the finest Scotch whisky ever made – the legendary Dalziel Double Proof – goes missing. 2023. Albie, youngest son of the wealthy Dalziel family, vanishes. His desperate mother turns to Robbie Gould, a disgraced reporter with a reputation as a 'psychic crimebuster'. Broke and unemployed, Gould is in no position to turn down the job. He throws himself into a twisted chain of criminals, bent cops and Japanese gangsters, but when someone fires a shotgun through his door, he realises he doesn't need supernatural powers to see how deadly the situation has become. 'A heady mix of corrupt coppers, dodgy drug dealers and Japanese gangsters, all spiced with dark humour' – Sally McDonald, Sunday Post

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 350

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A note on the author

Martin Stewart has worked as a recycling technician, university lecturer, barman, golf caddy and English teacher. His critically acclaimed first novel, Riverkeep, was longlisted for the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize. His children’s books are published by Penguin Random House and Zephyr, and have been translated into many languages. Double Proof is his first novel for adults. Martin lives on the west coast of Scotland with his wife and two children.

Published in Great Britain in 2024 by Polygon,an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

1

Copyright © Martin Stewart, 2024

The right of Martin Stewart to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978 1 84697 649 0

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 663 8

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by 3btype.com, Edinburgh

For G

Alcohol is a pervasive fact of life, but an extraordinary fact – pleasurable and destructive, anathematised and adulated, and deeply ambiguous . . .

Professor Griffith Edwards

Whisky is liquid sunshine.

George Bernard Shaw

July 2012

Boland and Durrant were parked beside the university, baking in the windless heat and counting the minutes until they could head back to Dumbarton Road for paperwork and coffee. It had been a quiet evening, by Partick standards. Even the football had finished without incident.

‘I don’t know how you can drink caffeine this late,’ said Durrant. ‘I’d never get to sleep.’

‘Years of night shift, son,’ said Boland. ‘One cup doesn’t even touch the sides. Anyway, what d’you think is in that rubbish?’

Durrant took a swig from his bottle, then angled his head to read the label. ‘Electrolytes.’

‘Uh-huh. Is that what turns your tongue blue?’

‘Electrolytes are,’ Durrant read on, ‘vital minerals that carry an electric charge.’

‘Oh aye?’ said Boland, pushing his spine into the seat and rolling his neck. ‘You must piss bolts of lightning.’

A taxi parked in front of them, spilling students on to the pavement. They bounced off each other, laughing. One of the boys gave a loud snort as they passed the car.

‘One more question?’ said Durrant.

Boland checked his watch: 9.53 p.m. ‘One,’ he said. ‘Pick a hard one. If I get it right, you get my Costa tomorrow.’

‘And if you don’t, you get my electrolytes?’ said Durrant, waggling his bottle.

‘Deal.’

Behind them, the students started singing the theme from Peppa Pig.

‘Right,’ said Durrant, leaning forward in his seat. ‘Here we go: name the only Scottish club whose name doesn’t contain any of the letters from the word football.’

Sergeant Boland’s first tutor had believed in notebooks, so Sergeant Boland believed in notebooks. Whenever his memory fed him lies, his written words told the truth, their ink fixed and incorruptible. He turned to a new page, wrote football and underlined each letter. ‘How long do I get?’

‘A minute.’

Boland crossed out a few letters. Rewrote the word. Started again.

‘Ten seconds left,’ said Durrant.

Boland squinted. Drew a line. ‘Dun-fucking-dee,’ he said.

Durrant’s shoulders dropped. ‘There’s an f in that.’

‘Get your hand in your pocket, wee man,’ said Boland. He checked his watch, gripped the keys in the ignition. ‘Right, by the time we’re back it’ll be–’

A young man was standing in front of the car.

‘Jesus Christ!’ said Durrant, hand on the door. ‘Fuck did he come from?’

Boland removed the keys, turned a clean page and wrote:

5’8/9

Slim

Late 20s/30

Slick dark hair

Shorts/shirt

The man was smartly dressed, the eyes, behind the thick-rimmed glasses, closed against the low sun. His empty hands were held palms out, and he was breathing deeply, as though basking in a fragrant wind.

‘Slim’ wasn’t quite accurate, Boland realised. The man was solidly built, a deep chest balanced on a narrow waist.

He drew a circle round the word, then added 12st+? to his list.

‘Looks like a fighter, sarge,’ Durrant said. ‘Could be spray time.’

Boland nodded. ‘Could be. I’ll go first.’ He got out of the car, putting on his hat as he stood. Durrant’s door went a second later, the constable holding back, hands on his belt.

‘Can I help you, sir?’ said Boland. He took a step.

The man opened his eyes and peered at a point somewhere behind Boland’s head. ‘I need to speak to someone.’

Boland went back to his notebook.

Sweating

They all were – it was still over 25 degrees. Glasgow felt like the continent on nights like this. It even, Boland thought, smelled a bit like being abroad. He wiped his face. The man, seemingly unaware of the beads of perspiration on his face and neck, didn’t match the gesture.

‘You can speak to me, sir,’ said Boland. ‘Maybe I can help.’

‘I live up there,’ the man said, pointing vaguely at the row of tenements. ‘Saw the car.’

‘That’s what we’re here for, sir. Is there a problem?’

The man nodded. ‘It’s about the wee Porter girl.’

Boland and Durrant shared a look.

Porter. Amy. Eight years old, missing for a week. There had been nationwide press coverage. A reconstruction was due on Crimewatch in a few days.

‘Do you have information you’d like to share with us?’ said Boland. He added Porter to the list.

‘No,’ said the man. ‘I need to speak to whoever’s in charge. Of the case, I mean. Whoever’s looking for her.’

‘Lots of people are looking for her, sir,’ said Durrant, stepping beside Boland, his body throwing a shadow across the man’s face.

Alcohol? Boland wrote, watching the big head roll. ‘If you have information relating to the public appeal–’ he started.

A rapid head shake, enough to throw him off balance. ‘It’s more than that.’

Boland waited. Shutters rolled noisily over a newsagent’s door, landing with a rifle crack on the pavement. ‘Sir, if you have something that could–’

‘I know where she is,’ the man said.

Boland’s heart squeezed into his throat. ‘Sir?’ he said.

‘I know where she is,’ the man said again.

Durrant got on the radio, started calling it in, switched on the blues.

‘And how do you know this, sir?’ said Boland.

The man sighed, emergency light flashing on his wet skin. ‘I just figured it out. Sam’s in the hospital, and I looked at it all, and I figured out where she is. Where Amy Porter is. I know who’s taken her. We need to go there. Right now.’

‘Two units on their way,’ said Durrant.

Boland approached the man, sniffed for booze, scanned his nostrils. Nothing.

The man turned his palms up, as though letting water run through his fingers, and looked at the sergeant for the first time.

His eyes, thought Boland. ‘What’s your name, sir?’ he said.

The man answered through the sound of approaching sirens, closed his eyes again.

Boland lifted his notebook.

Robert Gould

September 2023

11 p.m.

Gould looked outside. The pick-up truck was still parked opposite his driveway, Imelda Dalziel still in the driver’s seat. It was hard to tell through the rain, but he thought she’d stopped crying.

After sorting the recycling, Gould made two teas, pressing the bags hard. Blades of coastal night sliced under the doors, and he could hear tiles shifting as the squall hit the roof. He opened the front door, then set the mugs – one green, one pink – on the sideboard while he cinched up his dressing gown and tied on a plastic rain bonnet.

She wound down the window as he approached. Her eyes were red, the warmth that spilled from the car artificial as it hit the salty air. A look crossed her face when she saw the hot drinks, and she reached out.

Gould held back, slippers on the rooty pavement under the big sycamore.

Imelda withdrew her hands.

‘I told you I’m not interested,’ he said, taking a sip from the green mug.

She nodded. ‘I told you I wouldn’t leave unless you came with me.’

Gould took another sip. The rain moved up a gear, hissing on the pick-up’s windscreen and rattling on his bonnet. A swirl moved through the drain, its throaty gurgle echoing round the narrow street. ‘That’s no’ happening,’ he said, raising his voice.

‘Why not?’

He made a face. ‘Because you’re off your head, that’s why.’

‘We’ll pay you,’ she said, holding up an envelope. ‘Well.’

‘Aye, you said. But I told you this morning – I don’t do that kind of thing.’

‘You did it before.’

Gould took a longer drink from the green mug, burning his tongue. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Yes, you do. You’re Robbie Gould, the “psychic crime-buster”. You went to the police about that wee Paisley girl, and they got the guy because of what you told them.’

Gould held her eyes. ‘Being psychic isn’t a thing,’ he said, after a moment. ‘That is not how it was.’

‘But you did it! And if you can find her, then–’

‘I didn’t find her though, did I?’ Gould shot back. He stopped, settled himself. ‘He’d already killed her.’

‘My son isn’t dead. He’s–’

‘I want you to leave.’

She swallowed. ‘I’m not leaving unless you–’

‘You’re trespassing.’

‘This is a public road.’

‘Harassment, then. I could call the police.’

Imelda looked up through the streetlight-dappled sunroof, rested her head on the back of the seat and exhaled through her nose. Her hair was scraped into a greasy ponytail, and her skin looked waxy and tired. ‘Why come out here, then?’ she said, pressing the heels of her hands into her eyes.

Gould downed the last of his tea. ‘My programme’s finished. I always have tea after my programme.’

She looked at him, bare-legged and bulky in his dressing gown, rain bonnet tied over the stubble on his thick neck.

‘Found it in the hedge at the bowling club,’ he said, following her eyes. ‘Unbelievable. Can’t believe this is my first one.’

She sighed. ‘Bertie said your mumbo-jumbo might help.’

‘Bertie was wrong. Time to go.’

‘You helped that family,’ she snapped, almost leaning through the window. ‘They might not have got that wee girl in time, but her family got her back – and they got the man who did it! Why won’t you help us?’

Gould switched the pink mug into his right hand. ‘Because,’ he said, with a can-you-ever-forgive-me smile, ‘your son is a wee prick who’s kidnapped himself to impress some other wee pricks on YouTube, and I’m not remotely interested in being back in the papers or getting bags of shite put through my door.’

Imelda sagged, then reached for the tea.

Gould took a sip from the pink mug.

Day One

With export values topping £5 billion and investment returns in consistent double figures, the 1.3 billion bottles of whisky shipped from Scotland’s warehouses are turning plenty of heads, leaving the country’s national drink leading a pack of alternative investments that includes fine wine, artwork and jewellery.

In fact, as the stock market continues to tank, rare examples are drawing ever increasing sums from investors: a single ‘unique’ cask of Kippeny Single Malt sold at auction in Seattle for nearly $14 million.

Gold has been the investor’s safe haven for hundreds of years, but it seems the new gold – liquid gold – is about to snatch the precious metal’s crown.

Investment Bazaar, spring 2023 issue

1

Pale autumn sunlight made long shadows on Gould’s square of garden. A tree-bending wind had chased the rainclouds down the coast, and the sky was almost clear.

He took the bins out, waved at the shape between next door’s curtains and stretched with his face to the light. The air was dewy and cool, and he curled his bare toes into the grass. ‘Morning, Mrs Glennon,’ he said, as a door opened behind him. ‘Isn’t this glorious?’

‘Do up that robe,’ replied Mrs Glennon, kimono clutched to her throat. ‘People can see you.’

‘Lucky them.’

She tutted, then said, ‘That lady’s still there.’

‘I know.’

‘Is she a reporter? Are you being,’ she looked about furtively, ‘profiled again?’

‘She’s a victim,’ said Gould. ‘Or she thinks she is, anyway.’

Mrs Glennon shook her head, sunlight glowing through her white bouffant hair. She lit a cigarette and held it below her chin. ‘It can’t start up again, Robert, really it can’t.’

‘I know, Mrs G,’ said Gould, tying his gown before turning to face her. ‘It won’t.’

Mrs Glennon’s walnut face twisted into a scowl. ‘Sometimes they don’t know which house is yours, you know,’ she said, eyes widening, ‘and they put it through my door instead.’

‘I know.’

‘One time I thought it was a model submarine.’

‘I know, Mrs G. Don’t worry. I’m going to tell her again this morning, I’m no’ wanting involved. I’ve got a deadline coming up. Everything’s fine.’

‘Uh-huh. And what about romance?’

‘I think she’s just here about her kidnapped son.’

She waved off his cheek, blew a thin column of smoke over her head. Gould watched it swirl away. ‘You know fine what I mean,’ she said. ‘You had a dinner date this week, didn’t you?’

Gould wrinkled his nose. ‘Cancelled it.’

She gasped. ‘You did?’

‘Yes, I did. Can we have less of the shock, please?’

‘Well.’

‘Well what? What d’you think happened? She caught sight of me and ran?’

Mrs Glennon gave him a look. ‘I’ll get you married off again one day.’

He laughed. ‘You think so?’

‘Absolutely. I mean, the Knit and Natter girls think you’re handsome. And you can talk.’

‘I’ll add that to my profile.’

They stood for a moment. Gould looked past her to the Isle of Arran, its quilt browning with the season. A tuft of cloud had snagged on the mountain, and he watched it gradually tear free, leaving the hillside bright and clear.

‘Thank you for those wee booties,’ said Mrs Glennon.

‘No bother,’ said Gould. ‘I’m glad someone can use them. How many grandkids is that now? Six?’

Mrs Glennon dropped the cigarette under her slipper. ‘Seven. This one’s huge.’

Gould rolled his eyes. ‘She’s a healthy wee girl,’ he said. ‘I’m sure–’

‘I’ve had husbands that weighed less, Robert.’

Gould shut his mouth.

‘I just think you’ve been on your own too long,’ said Mrs Glennon, nodding as her cast-iron barrow of opinion found its well-worn groove. ‘It’s just you and your stories.’

Gould closed his eyes. ‘They’re novels, Mrs G.’

‘Novels, then. I started the last one, you know. City of something.’

‘Forevermore,’ said Gould.

She inclined her head. ‘That’s what it felt like.’ Another puff. ‘I couldn’t make head nor tail of it.’

‘Well, thanks for trying,’ said Gould.

‘What about that other thing you’ve been working on? The proper book?’

‘I’m nearly done.’

‘You said that last year.’

Gould puffed out his cheeks. ‘Whose side are you on?’ he said. ‘It’s a process. Rest assured, I’m perfectly happy.’

Mrs Glennon’s mouth puckered, as though an unpleasant meal was repeating on her. ‘Nobody could be happy in those pyjamas,’ she said.

Gould glanced at himself as she closed the door, then went into his kitchen.

Imelda’s pick-up was indeed still there. She’d been up to the services: her silhouette included a takeaway cup. Gould swore under his breath and poured coffee beans into the grinder. While the machine howled them into powder, he lifted his moka pot from the greasy sink and wiped it on his dressing gown.

He watched the flame as it boiled while, gradually, like oil seeping under a locked door, the past slid into his mind. Glasgow. Samantha. And how he’d felt when the answer to the Porter case had arrived fully formed in his head. Composed. Strong. As though he was moving on rails. Everything had seemed effortless, and known, as if he’d peeled back the skin on the world and was watching its tissue shift in a pattern only he understood.

It had been – as he’d told his therapist during the Robbie the Ghoul stuff, after Samantha had left him, after he’d packed on two stone and been knocked cold in the ring for the first time in his life – transcendent.

He poured the tar-black coffee, settled on his bar stool and opened his phone.

First, he put on Oscar Peterson: ‘Blue And Sentimental’.

Next, he read the paper. Politics. Sport. Labour were this, Rangers were that. All a pantomime: all important, all meaningless. He drank while he scrolled, Oscar giving way to Chet Baker as the boiler growled and the shower dripped into the bath over his head.

Finally, coffee gone stale, he checked his emails.

Five. Three from mailing lists, one disguised as a reply. He deleted them unread, enjoying the pull and snap as they disappeared. The remaining two were from his supermarket and his agent. His delivery of groceries had been cancelled. Sorry for the inconvenience. His order would be held in store for the remainder of the day, and as compensation he would receive a voucher for two pence off a litre of fuel.

He read Sandra’s email. Two paragraphs of preamble – her cat died, her brother remarried, the events apparently unconnected – then the nugget: his contract had been terminated.

Gould put his mug in the microwave and sipped at the newly scalding coffee.

Sandra was angry but powerless. The small Edinburghbased publisher was very sorry. The circumstances were unforeseen. The Canticle of Venus was a special book. He was invited to keep the advance paid thus far. When his eyes slid across a reference to the impact of the pandemic, he stopped reading.

Great, he thought, checking the bread bin. I get to keep the twelve hundred quid I spent six months ago. A bag of white factory loaf lay curled in the corner. Poor starving bard, Gould thought, how small thy gains.

He tightened his robe and went out the front door.

The sea was choppy, mayfly rainbows in the rock-spray and sun. He stamped over the road, holding up a hand to stop Imelda before she climbed from the truck. She got out anyway, started running towards him. Gould dropped heavily into his car, threw some wrappers on to the passenger seat and turned the key.

His car – a ’98 Citroën ZX – didn’t even splutter. He tried again. Like an animal crying out at the point of death, the electrics flared, once. Gould swore, thumped the wheel, sat back and dropped his hands, letting the keys swing in the ignition. The vehicle felt suddenly very cold and very heavy.

‘If this was a horse . . .’ Tam, his mechanic, had said.

Gould had nodded. ‘Dog meat and glue?’

‘You couldn’t feed this thing to a dug, pal,’ Tam had concluded, wiping his knuckles on a rag. ‘It’s toxic.’

Imelda motioned for him to wind the window down. Gould opened the door. ‘Look, how many–’

‘We’ve had a ransom demand,’ she interrupted. ‘Last night. Now do you believe me?’

Gould started to say that Albie Dalziel was perfectly capable of phoning in his own ransom demand, that the audio from the call would probably end up on his channel complete with sound effects and dancing emojis. Then he saw the envelope in her hand, its surface furred where her fist had been massaging it for nearly thirty hours.

He took a deep breath, let it out slowly. ‘What’s the fee?’

‘Six thousand. Two now. The rest when you find him.’

Gould grabbed the envelope and glanced inside. ‘Ten thousand. Five now, the rest in a month – whether I find him or not. But first, you can take me to get my shopping.’

Imelda hesitated. ‘You work for me now, yes?’

‘I suppose so,’ said Gould. He nodded. ‘Aye.’

She glanced down at his bare knees, skin pressed white on the steering wheel. ‘Then put some bloody trousers on.’

2

‘Nice place,’ said Gould, looking at the Victorian terrace as Imelda flicked on the handbrake. ‘This where the SFA used to be?’

‘Round the corner.’

Gould wrapped his lips around the end of another croissant. ‘I used to live up here,’ he said, spraying crumbs. ‘Over by the uni.’

She brushed at the seat, pushing his leg out the way. ‘Bertie’s waiting for us inside.’

‘Remind me,’ said Gould, taking another bite.

‘My brother-in-law. Albie’s uncle.’

Gould nodded, then followed her out of the pick-up. Kelvingrove Park whispered opposite, the pavement soggy with its fallen drifts of red and gold. The air was noticeably colder in the city than on the coast. Gould flicked up his collar and finished his breakfast. ‘Is Bertie in charge of the whisky stuff?’

‘He runs the family’s affairs,’ she said, stamping on the mat at the top of the steps.

‘Including whatever whisky’s left?’

She looked at him. ‘He looks after all the family assets. Some of that is in whisky. Is that relevant?’

Gould snorted. ‘With your family? Everything’s relevant.’

‘Mr Gould–’

‘Robbie.’

‘I just want you to find my son. I’m not interested in anything else.’

‘That’s fine,’ said Gould, stepping into the marble hall. ‘But if I’m going to do that, it’ll be by asking questions. About everything. I’m not just going to sniff one of his fucking trainers and have a vision.’

She turned. ‘What do you–’

A door burst open and out swung a vision of denim and tweed, heels clicking with a report that echoed up the ornate stairwell.

‘You must be Robert,’ said Bertie Dalziel, running a hand through his hair before offering it to Gould. ‘Hi, hi, yes, come in, come in. I’m so excited about your specialist insight, and Immy assures me that you’re the top man with a record to boot, so we are glad of your help!’ He slapped the last four words onto Gould’s shoulders.

‘About that record . . .’ Gould began.

‘I would have come to collect you myself,’ Bertie went on, ignoring him, ‘but Immy insisted – you know, mother’s prerogative and all that.’ He looked down. ‘Oh, socks and flip-flops is a bold choice for late September.’

‘This outfit was a big improvement,’ said Imelda, hanging up her coat and reaching for Gould’s.

‘I’d call these sliders,’ said Gould.

‘Ha-ha!’ crowed Bertie, hands clasping over his tucked-in stomach. ‘Yes! Wonderful, how recherché! And shorts in the autumn . . . well, well. Come into the lounge, let me get you a cup of something.’

‘I like your boots,’ said Gould, allowing his arm to be taken. ‘You should have spurs on those things.’

‘I absolutely should!’ roared Bertie, steering Gould into a room with tartan carpet and tartan walls. ‘We could ride off into the sunset together: you in your sliders and me with my spurs. Wouldn’t that be lovely? Tea?’

‘Coffee, thanks,’ said Gould, perching on the edge of a sofa the size of his living room.

The space was huge – sixty or seventy feet, Gould reckoned – and shelved with glassware and bottles, their amber contents spotlit and glowing. There were photos everywhere, black-and-white images featuring Bertie and some other men – the brother and the old man, Gould assumed – shaking hands with politicians, footballers, and an international gaggle snapped in front of monuments and flags. At the far end of the room, a gigantic painting of a rainbow-coloured Highland cow, tongue stretching for a morsel beside its ear, gazed down like a benevolent god.

Gould inspected one of the photos. Bertie was shaking hands with a familiar figure in front of a tricolour flag. Is that Colonel fucking Gaddafi? he thought.

Imelda slipped through the door and leaned on the radiator, pressing her hands to the heat.

‘Latte? Cappuccino?’ said Bertie.

‘A cappuccino would be magic, thanks. Two sugars.’

‘A man after my own heart! I’ll be back in two ticks.’

‘You not having anything?’ said Gould, as the heel-clicks faded down the hall.

Imelda shook her head. ‘I’ll get myself a tea. What you were saying before, is that true?’

‘Oh, aye,’ said Gould, settling back on the cushions. ‘I think he’d suit spurs.’

‘I don’t mean–’

‘I know. And yes, it is. I told you last night, didn’t I? The stuff in the papers – especially the stuff afterwards – was a lot of shite.’

‘I googled you,’ said Imelda, her eyes wild. ‘The Record called you the “psychic crimebuster”.’

‘They called me worse than that.’

‘But you went to the police with the whole case solved – and you were right. About all of it.’

Gould was already shaking his head. ‘But I never said I was psychic. To anyone. Ever.’

‘Then why have you taken my money?’

‘Because,’ said Gould, with a gesture that took in Imelda’s person, expression and attitude in a single movement, ‘you camped outside my house and begged me to take it.’

The colour was draining from her face. ‘I don’t understand. Is none of it true? Did you even go to the police?’

‘Aye. But if I was psychic, I’d have known it was too late and how much of a disaster it would be.’

‘But that wee girl–’

‘Amy Porter,’ interrupted Gould. ‘Nobody ever uses her name, do you know that? It’s always “that wee girl” or “that poor lassie”. Everybody uses his name all the time. But not hers.’

Imelda said nothing. She sat opposite, in a stiff-backed, ornate chair.

Gould looked at the floor between her boots. ‘If I was psychic,’ he went on, ‘I’d have seen it sooner, wouldn’t I? But I didn’t – it was too late, and all this, the psychic shite . . . it ruined me.’

‘How?’

‘Take your pick. I was a cub reporter who’d just written a feature on the tabloids bribing police for access to crime scenes, so when my involvement in the Porter case was leaked, the press went for me – big time. Made out I was his accomplice. I started getting bullets in the post. My wife left me. I lost my job. Lost my belts. Everything.’

She stared at him. ‘And you really didn’t have a psychic reading on it? Nothing?’

‘No,’ said Gould, showing her his empty hands. ‘I just read about the case in the paper, same as everyone else, wrote it all down and saw it.’

‘Saw what?’

He shrugged. ‘The answer.’

She closed her eyes, dragged her hands over her face. ‘You can’t tell Bertie any of this, all right?’

‘Why?’

‘Because,’ she said, speaking through her teeth, ‘he knocked back every private eye I could find – except you. Said there was no point in hiring someone when the police were already looking, and only changed his mind when I mentioned the Porter case. You’re my last chance. I need you to find my son, and if Bertie finds out you’re just some bum who got lucky–’

‘Hold on a minute–’ said Gould, over the sound of clicking heels.

‘–he’ll take that money straight back. And you need that money, don’t you, Robbie?’

Gould held her eyes. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I do.’

‘Right. Then keep up the act – because as far as Bertie’s concerned, you’re a psychic investigator. That’s what he’s paying for.’

Gould rolled his eyes.

‘What?’ she hissed.

‘If I’d known I was supposed to be a crack spookologist, I’d have worn my good sliders.’

Bertie trotted into the room, tray held proudly at chin height. He stopped and tilted his head. ‘Immy, I forgot you, didn’t I? Here, you can have mine.’

‘It’s fine,’ said Imelda, slumping into the chair. ‘I’m okay.’

‘Right,’ said Bertie, handing Gould a glass mug. ‘Down to brass tacks, as they say. I’m sure Immy’s told you all about it. We need your help – your specialist help – to find Albert.’

‘He named after you?’ said Gould, sucking froth from his moustache.

Bertie smiled. ‘He was. Howard, my brother, he did that. Immy wanted to call him Jasper.’

Imelda sighed.

‘Well,’ said Bertie, eyes flashing over the edge of his mug, ‘in any case, yes, my nephew was named after me, and we’ve always been very close. This is the family pile, you know. Albert lived here. We all stayed here, together – even before Howard died.’

‘When was that?’ said Gould.

‘Five years ago,’ said Imelda. ‘Cancer.’

‘And everything passed to you?’ said Gould, looking at Bertie.

‘I had run things while Howard was ill, and when he passed I was given responsibility for the family’s assets. Of course, by that time Howard had sold the distillery to one of the big boys. Le Canard.’

‘When was that?’

‘It’ll be nine years in November,’ said Bertie. ‘They folded the label completely. Now our grand old stills are used for some rancid blend I wouldn’t use to clean the boiler.’ He shook his head. ‘Are you a whisky man, Robert?’

‘Robbie,’ said Gould. ‘No. It all tastes like fire to me.’

Bertie gasped. ‘Heresy! Oh, but you must try some of our old bottles. Wonderful. Speyside, you know; the best whiskies are all Speyside.’

Gould slurped some more coffee. ‘Was Albie interested in the whisky stuff?’

‘Ha!’ cried Bertie, throwing his head back.

‘No,’ said Imelda. ‘He thought it was embarrassing, coming from such an old tradition. He’s very active on YouTube, social media. He was building a career–’

‘As an influencer?’ said Gould.

‘That’s right.’

Bertie scoffed. ‘Influencing who, I ask you?’

‘Wee fannies online?’ hazarded Gould.

‘Robbie’s current theory,’ said Imelda, holding up a hand to silence Bertie, ‘is that Albie has kidnapped himself for likes.’

‘Likes and lols,’ added Gould.

Bertie looked between them, jollity draining from his face. ‘You told him about the ransom demand?’

‘He could have made that call himself,’ said Gould, draining his mug. ‘Or got one of his pals to do it. Like I said, it’s just a theory.’

Bertie looked furious. ‘They’re looking for half a million pounds, Mr Gould.’

Gould frowned. ‘Is that all?’

‘All?’ cried Bertie. ‘It might as well be a hundred million! We might seem well-to-do, but we do not have that kind of money – and certainly not the liquidity to pay it in a matter of days!’

‘Was that what they asked for? Payment in . . . ?’

‘Three days,’ said Bertie. ‘It was a machine voice, you know, like a robot. Half a million into some offshore account, paid within three days. Or they’ll kill him.’

Imelda let out a sob.

‘When did Albie go missing?’ said Gould.

She settled herself, wiped her cheeks. ‘Last Thursday. There’s been a call every night since: threats, Albie’s breathing. And now the ransom.’

Gould raised an eyebrow. ‘Five days ago?’

‘As I said, the police have been looking,’ said Imelda, fighting for composure, ‘but . . .’

Bertie took over, his thick brows low. ‘Albert Junior is an adult – fully nineteen. His disappearance isn’t a priority for the police. Their attitude in the last few days has been much like yours, in fact.’

‘Healthy scepticism?’ said Gould.

Bertie’s lip curled. ‘Poisonous cynicism.’

Gould nodded. ‘But they must be taking the ransom demand seriously?’

‘It certainly changed their tune,’ said Bertie. ‘But Immy felt – we feel – that we need to take matters into our own hands. Hence . . .’ He gestured impatiently at Gould.

‘Ever done anything like this before?’ said Gould. ‘Taken off with his pals or anything?’

‘No,’ said Imelda, firmly. ‘Never.’

‘Did the caller say who they were? Any hint of why they might be doing this?’

‘We know why they’re doing this!’ Bertie snapped. ‘It’s the bloody court case, isn’t it? They think that if they drain all our resources, we won’t be able to fight them in the courts.’

‘Aye, the court case,’ said Gould, remembering the newspaper reports. ‘About that lost whisky?’

‘“That lost whisky”,’ Bertie echoed. ‘The Double Proof, yes. That reprobate Mears thinks he has finder’s rights, but he’s wrong. It was stolen from Dalziels. When we win – and we will – we’ll get it all back. It will be the making of us. Or, rather,’ he added, moving to where Imelda was slumped, elbows on her knees, ‘our restoration.’

‘Worth a lot of money, is it?’ said Gould.

‘Millions,’ said Bertie.

‘How many?’

‘There’s sixty-one bottles, each estimated at between two hundred and two-fifty,’ said Imelda.

‘Thousand,’ added Bertie.

Gould whistled. ‘So, that’s . . .’ he said, squinting as he ran the numbers, ‘what, fifteen million, give or take? For some burny juice?’

Bertie drew himself up. ‘The Double Proof, Mr Gould, is the finest whisky Scotland has ever produced. There are only those sixty-one bottles in existence, and they’ve been missing for over fifty years. Some people actually believed the bottling was a modern myth – the Bigfoot of Scotch – until Mears Reclamation suddenly announced its discovery in May. No bottle in the world is so sought after by collectors, and we won’t have to bend the knee for Fabergé packaging or get a bunch of artists to paint our labels. The Double Proof will change the entire spirits industry when it auctions, and we will be at the hammer.’

Gould took a notebook from his bag, opened a clean, two-page spread. As they watched, he wrote Albie Dalziel in thick letters and drew a circle around the words. ‘It’s weird Albie’s disappearance wasn’t in the papers over the weekend,’ he said. ‘I know there were some stories on Friday, but you’d think the red tops would be all over something like this.’

Bertie went out to the hallway. ‘We’ve endured enough,’ he called, ‘and have managed to keep the press fairly quiet’ – he reappeared, a sheaf of newspapers under his arm – ‘until today.’ He dropped them – Herald, Scotsman, Record, Mail and the rest – on to the coffee table before returning to his position behind Imelda.

Albie Dalziel, all dimples and dangling curls, grinned out from the front pages – right under a picture of Gould in his dressing gown, drinking tea beside Imelda’s pick-up.

ROBBIE THE GHOUL – BACK FROM THE CRYPT

LOOK WOOOO DALZIEL DUG UP

DALZIELS HIRE PORTER ‘PSYCHIC’

‘Ah,’ said Gould.

Imelda reached out, ran her fingers over her son’s face. ‘He just wouldn’t do something like this. Not without calling. He’s in danger – I know he is.’

Gould stood. ‘I suppose I expected a bit of negative press,’ he said.

‘If it keeps Albie on the front page,’ retorted Bertie, placing his hands on Imelda’s shoulders, ‘there’s nothing negative about it.’

Gould turned over the Mail. ‘If you say so,’ he said, running a hand along his jaw. ‘Can I see his room?’

‘Of course,’ said Imelda, standing and dislodging her brother-in-law’s hands.

Like the sun breaking through a cloud, Bertie’s eyes lit up. ‘His bedroom? Of course. I mean, the police have already been through it, but–’

‘I just need to check out his environment,’ said Gould. He caught Imelda staring at him. ‘Connect to his aura, maybe give his trainers a wee sniff, that kind of thing.’

Bertie pursed his lips. ‘Is this the mumbo-jumbo?’ he said, reaching for Gould’s hand.

‘Aye,’ said Gould. He glanced up. ‘I think there’s a decent chance of finding some jumbo upstairs.’

Imelda moved towards the door.

‘I remember the Porter case,’ Bertie said. ‘Very impressive. Immy will show you Albie’s quarters. Just let us know what you need – our limited resources are at your disposal.’

Gould joined Imelda at the foot of the wrought-iron staircase. ‘That convincing enough?’ he said. ‘Or should I have read his palm?’

‘It’s this way,’ she said, turning, her feet heavy.

Gould added another scribble to his notes and climbed after her.

3

On the other side of the city, Hideo Inamoto paid for his shopping – a couple of pints of milk, Irn-Bru, vegetables, tins of mackerel, two bananas – and loaded it into his tote. The windows of Atwal’s grocery were obscured behind posters and shelves. Dust sparkled in the sunshine around the shopkeeper’s head.

Inamoto put on his sunglasses and bowed through the gloom.

‘No bother, pal,’ said Atwal. ‘You’re fair tanking that ginger. Bottle a day! Maybe get you on square sausage next.’

Inamoto nodded politely, his neat frame shadowed in the flashbulb of the open door.

Outside, he dodged a pram and turned up the hill, pulling his polo neck up to his ears and rubbing his hands together. It was cold – ten degrees below Saitama – and he hadn’t packed for it: no layers, no down. The apartment’s heating was temperamental, the walls of both bedrooms bruised with damp. Inamoto had woken that morning under a vapour of his own breath.

And the food . . . It had been a long week, and there was still another full day until they arrived.

He stopped to drink an espresso at the bar of the blue café; then, cupping a flame behind his fingerless gloves, he knocked a Seven Star from its pack and sent a needle of smoke into the air.

Whether he had been selected in praise or admonition remained opaque. It was work. He had been sent first, and yet . . . he had been sent first. It was something or nothing. He was here. That was that.

Glasgow was not what he had expected. The city was somehow both larger and smaller than he’d imagined, the neighbourhood to which he was confined too quiet, too dull. He glanced up at the empty discs of the old hospital’s Victorian balconies, imagining them alight with Tokyo neon.

A garbage truck rattled downhill, leaves spinning in its wake. Inamoto brushed down his suit and checked his watch. Nine thirty-five, and his day’s errands were already complete.

He ate one of the bananas.

It was dinner time on the other side of the world. Kumiko – who had watched Massan every day when she was pregnant – would be running around the kitchen while Mayumi did her homework.

A gossamer skin of their warmth, smells and touch settled on him for a slow moment, then whipped away on the wind.

Inamoto watched it go, feeling colder, more alone – as if he was losing something he’d held in his fist.

No more, he thought. When he got home, he would ‘wash his feet’.

A woman and her son joined him at the kerb. The boy was eating a kiwi fruit with a spoon and returned Inamoto’s smile with a gappy grin. As they waited to cross towards the auto shop with the smiling tyre, he checked his packet of Seven Stars.

Only three left.

He’d have to buy Scottish cigarettes. Perhaps, he thought, stepping out, he could show these to Atwal. The shopkeeper might know which brand was the closest match, and . . .

The car hit him below the right knee, snapping his leg and crushing his foot below the tyre. His skull smashed against the grille, splitting his forehead and shattering his eye sockets before he was pulled under and dragged along the road, his tearing suit exposing ornate tattoos.

As the car sped away, Inamoto’s shopping scattered, the milk glugging on to the street, the brilliant white of his last cigarettes dissolving in the blood around his head. People were running towards him. There was shouting.

Amongst the chaos and scattered glass, Inamoto lay broken, unmoving, every part of his body perfectly still.

Except for the tip of his little finger, which – tearing free as his hand mangled through the wheel – had shot into the boy’s open mouth, striking the back of his throat and causing him, reflexively, to swallow.

The boy spluttered, dropped his spoon – and screamed.

4

Albie Dalziel’s bedroom was immaculate. Gould picked his way through it, leaving soundless footprints in the carpet.

The air smelled of cologne. A mirror surrounded by hair products was propped on the drawers. Albie’s floor was lined by the tracks of a vacuum cleaner – Gould dimly remembered the process – and there were fairy lights around the headboard, arranged in a thrown-together jumble that had obviously taken hours to perfect.

‘Tidy boy, isn’t he?’

‘Even when he was wee,’ said Imelda, gripping the door handle. ‘You shouldn’t have wound Bertie up like that.’

Gould snorted. ‘He seemed quite happy. What’s his star sign? I’ll drop it in next time I’m speaking to him.’

She waited to see if he was serious. ‘I don’t know,’ she said, eventually. ‘His birthday was a couple of weeks ago, if that helps.’

‘How old was he?’

‘Fifty-three.’

‘Aye?’ said Gould, puffing out his cheeks. ‘Jesus.’

‘You thought younger?’

Gould wrinkled his nose. ‘God, no. He looks like he drank out the wrong cup in Indiana Jones. Albie not have a telly in here?’

‘It’s in the bed.’ Imelda pressed a small remote and a panel flipped back in the foot of the bed. A glossy, thin television rose level with Gould’s eyeline.

‘Very different to my teenage bedroom,’ he said. ‘Framed art . . . I just had posters. And my commitment to self-abuse would never have survived such a dark carpet.’

‘What are you looking for here?’ said Imelda, sliding the TV back out of sight.

Gould shrugged. ‘Anything I can find.’