Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

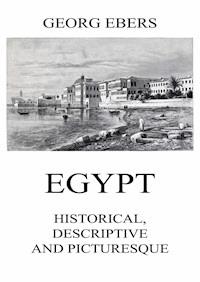

Wherein lies the mysterious attraction which is peculiar to the land of the Pharaohs? Why is it that its name, its history, its natural peculiarities, and its monuments, affect and interest us in a quite different manner from those of the other nations of antiquity? Not only the learned and cultivated among the inhabitants of the Western world, but every one, high and low, has heard of Egypt and its primeval wonders. The child knows the names of the good and the wicked Pharaoh before it has learnt those of the princes of its own country; and before it has learnt the name of the river that passes through its native town it has heard of the Nile, by whose reedy shore the infant Moses was found in his cradle of rushes by the gentle princess, and from whose waters came up the fat and lean kine. Who has not known from his earliest years the beautiful narrative, which preserves its charms for every age, of the virtuous and prudent Joseph, and heard of the scene of that story-Egypt-the venerated land where the Virgin, in her flight with the Holy Child, found a refuge from His pursuers? To answer these and more questions the writer of these pages, who knows and loves Egypt well, has with pleasure undertaken the task of collecting all that is most beautiful and venerable, all that is picturesque, characteristic, and attractive, in ancient and modern Egypt, for the enjoyment of his contemporaries and for the edification and delight of a future generation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Egypt

Descriptive, Historical and Picturesque

GEORG EBERS

Egypt, G. Ebers

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849650209

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

Availability: Publicly available via the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA) through the following Creative Commons attribution license: "You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work; to make derivative works; to make commercial use of the work. Under the following conditions: By Attribution. You must give the original author credit. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above." (Status: unknown)

Translator: Clara Bell (1834 – 1927)

CONTENTS:

Preface.1

Introduction.4

Ancient Alexandria.11

Modern Alexandria.30

Goshen.61

Memphis And The Pyramids.78

Cairo; The Origin Of The City.113

Cairo; Under The Fatimites And Eyoobides.138

Cairo; Under The Mameluke Sultans.154

Cairo In Its Decadence; And Its Tombs.177

PREFACE.

WHEREIN lies the mysterious attraction which is peculiar to the land of the Pharaohs? Why is it that its name, its history, its natural peculiarities, and its monuments, affect and interest us in a quite different manner from those of the other nations of antiquity?

Not only the learned and cultivated among the inhabitants of the Western world, but every one, high and low, has heard of Egypt and its primeval wonders. The child knows the names of the good and the wicked Pharaoh before it has learnt those of the princes of its own country; and before it has learnt the name of the river that passes through its native town it has heard of the Nile, by whose reedy shore the infant Moses was found in his cradle of rushes by the gentle princess, and from whose waters came up the fat and lean kine. Who has not known from his earliest years the beautiful narrative, which preserves its charms for every age, of the virtuous and prudent Joseph, and heard of the scene of that story—Egypt—the venerated land where the Virgin, in her flight with the Holy Child, found a refuge from His pursuers?

But the Holy Scriptures, which first familiarise us with the land of the Nile valley, say nothing of its Pyramids and other monuments of human labour, which, apparently constructed to endure for ever, seem as if they were not subject to the universal law of the evanescence of all earthly things. And yet who has not, while yet a child, heard of those monuments, on which the Greeks bestowed the proud name of “Wonders of the World”?

The name “Pyramid” is given to a simple mathematical solid form, which frequently occurs in Nature, and the name was derived from the Egyptian structures which have that form, not vice versâ; just as we call any confused and complex arrangement a “Labyrinth,” from that magnificent palace, built by Egyptian kings, from whose intricate series of chambers it was difficult to find an issue. Thus, too, “Hieroglyphic” has come to mean any idea veiled by its mysterious mode of exposition—another metaphor derived from the picture-writing of the ancient Egyptians. Every day and every hour, though generally unconsciously, it is true, we have something to do with objects and ideas whose first home was the land of the Pharaohs. The paper on which I write these words owes its name to the Egyptian Papyrus, which was also called Byblos, whence the Greek word Βιβλος and our word Bible. A hundred other current words and ideas might be mentioned whose native land is Egypt, and if it were here possible to go deeper into the matter and to lay bare the very roots of the artistic possessions and learning of the West we should find more and more reason to refer them to Egypt; but we must not in this place linger even at the threshold of this inquiry.

We invite the reader, in these pages, to accompany us to Egypt. Enchanting and quite peculiar it remains to this day, as when Herodotus, the father of history, declared that the valley of the Nile contained more marvels than any other country; and just as the climate of Egypt is exceptional, and the great stream itself differs in character from every other river, so the inhabitants of the land differ in almost every respect from other nationalities, as much in their manners as in their laws.

The Nile with its periodical fertilising overflow, the climate of the country, and many other circumstances, remain just as Herodotus described them, and the lapse of time has had but little effect even to this day in counteracting the influence of the natural peculiarities of Egypt. The customs and laws, it is true, are wholly changed, and only a diligent inquirer can find in those of the present day any relies or records of antiquity.

To the Pharaonic period succeeded the Greek, the Roman, the Christian; and after all these came the dominion of Islam, the unsparing revolutioniser. At the present day a sovereign sits on the throne of Egypt who is striving with success to adapt the forms of European culture to his Mohammedan subjects; but Civilisation, that false and painted daughter of the culture of the West, with her horror of all individuality and her craving for an ill-considered and monotonous equality, has forced her way into Egypt, and robs the streets and market-places in the villages and towns of the magical charm of their primitive character, sprung of the very soil of the East; she finds her way into the houses, and in place of the old luxurious abundance of space she introduces a meagre utilisation of it; she strips the men of the stately splendour of their flowing robes and decorated weapons; and makes the women covet the scanty draperies and smart clothing of their envied European sisters. The whistle of the steam-engine, as it drives across plain and desert, laughs to scorn the patient strength of the camel and the docile swiftness of the Arab horse; the uniform and arms of the soldiers are made to resemble those of the West more and more. The people's festivals still preserve their peculiar character, but European carriages are beginning to supplant the riding horse, and Egyptian military bands play airs by Wagner and Verdi. In well-appointed Arab houses sofas and cabinets from Europe are taking the place of the divans and beautifully carved or inlaid chests, and coffee is no longer sipped from a “Fingan” of finely chased metal, but from cups of Dresden china. All the stamp and character of the East in great things and small are being more and more destroyed and effaced, and are in danger of vanishing entirely in the course of years.

As yet, however, they have not entirely disappeared; and the artist, as he wanders on through the towns and villages, by streets and houses, under the wide heaven and in the tent, among the magnates and the citizens, the peasants and the sons of the desert, at the solemn occasions of rejoicing or of mourning; as he watches the labours or the repose of the dwellers by the Nile, may still detect forms of antique, various, picturesque, attractive, and characteristic beauty.

Glorious remains of the three great epochs of art—the ancient Egyptian, the Greek, and the Arab—still survive in Egypt. The last, indeed, will endure a little longer; but much of what is most fascinating in the peculiarities of Oriental life will have disappeared within a decade, much even before a lustrum has passed —everything probably by the beginning of the next century.

For this reason the writer of these pages, who knows and loves Egypt well, has with pleasure undertaken the task of collecting all that is most beautiful and venerable, all that is picturesque, characteristic, and attractive, in ancient and modern Egypt, for the enjoyment of his contemporaries and for the edification and delight of a future generation.

Yes! for their delight; for the pictures, which it is his duty to explain in words, are unsurpassed of their kind. Our greatest artists and most perfect connoisseurs of all that the East can offer to the painter's art have produced them for us, and Egypt is thus displayed not merely as it is, or as it might be represented on the plate of the photographer, but as it is mirrored on the mind of the artist.

In treating of the solemn festivals held by the Cairenes, and of the tales they narrate, Dr. Spitta, of Hildesheim, the librarian to the Khedive, has given much valuable assistance; and Dr. J. Goldhizer, of Buda-Pest, an accomplished and well-known Orientalist, who was himself one of the students in El Azhar, the University of Cairo, has contributed a fine chapter on that centre of Mohammedan life and Mohammedan science in Cairo.

Those who already know Egypt will in these pictures find all that they have seen illuminated by the magic hand of genius; those who hope to visit the Nile valley may learn from these pages what they should see there, and how to see it; and those who are tied to home, but who have a desire to learn something of the venerable sites of antiquity—sacred and profane—of the scene of the “Thousand and one nights,” of the art and magic of the East, of the character and life of Orientals, will here find their thirst for knowledge satisfied, and at the same time much to interest them and give them the highest kind of pleasure.

GEORG EBERS.

LEIPSIC, 1878.

INTRODUCTION.

HOW often has that wonderful land—the subject of the present work—been visited and described, from the time of Herodotus in the sixth century before Christ to the nineteenth after! What numerous narratives of its history, its monuments, its physical condition, and its political state, have flowed from a thousand pens! How many eyes have scrutinised its remotest nooks, with a view to its condition—past, present, and future! What, after all, is Egypt—the gift of the river, the products of the Nile, the bed of that old serpent of the waters, varying with the change of season, broad in winter, narrow in summer, by turns sheeted with water like a lake, or the slimy dark alluvial of a marsh, or else verdant with vegetation, or yellow with the harvest—the granary of the Old World, the cotton, tobacco, and indigo field of modern times, with its five millions of acres of cultivable land and its four millions and a half of population, with a river of fifteen hundred miles for its highway, at the edge of the Libyan Desert, close to the Red Sea, remote from the Atlantic, bathed on its north coasts by the Mediterranean, clinging to Asia by an isthmus, which, now divided by the thin streak of a canal, makes Africa a gigantic island? Egypt, too— the result of the outpour of the great African lakes—the reservoirs of the tropical rains—with its rainless sky, its tropical climate, has from times remote had the charm of historical recollections—the first cradle of the human race, the earliest evolution of civilisation, the oldest theatre on which the great drama of mankind was played, with all its shifting scenes and startling incidents. To Egypt also point the arts and sciences as the cradle of their earliest infancy: sculpture, architecture, and painting, there first started forth from small beginnings; literature there began; and religion, the mental bond of civilised communities, there sprang into life, with all its Protean phases of polytheistic forms.

Whence came the first man who trod its alluvial plain? Was he a rude savage, clad with skin, and equipped for the chase with implements of stone, to do battle with the hippopotamus and the crocodile, with which the stream and its estuaries abounded, or to spear the African lion, hunt the howling hyæna, or shoot the countless flocks of birds of the banks of Nile? Came he as a Nigritic wanderer, from Equatorial Africa, from the fringe of the Libyan coast, or from the Semitic races beyond the Suez isthmus? Was he an aboriginal—some type of mankind which, blended with all sorts of races, has melted away and left no representative except some occasional and abnormal form, such as Nature throws out from time to time like a recurrent thought in the cosmic mind, some dim recollection of a vanished past? The long duration of civilisation has cleared away, even from the preserving valley of the Nile, nearly all the evidences of palæothetic ages or neolithic remains, although here and there fragments attest the use of stone prior to the employment of metal, but so rare as to cast shadows of doubt on the existence of prehistoric man.

This Egypt, whose tradition recounts the reign of gods and demi-gods, first gives evidence of its existence by its Pyramids—those tombs of geometric form which prove the highest knowledge of the exactest of the human sciences, raised with wonderful care, and evincing unrivalled knowledge of the principles of construction. They show an enormous population, a long antecedent period of human experience, and a development of technical skill in its way unrivalled at the present day, a combination of profound thought and trained dexterity evolved by motives of intense belief and religious enthusiasm, while at the same time everything necessary to an advanced civilisation marked the period, minute divisions of the religious systems and civil administration, a practical knowledge of all the arts and sciences, without which architectural conceptions would be failures, the conquest of the Arabian peninsula and search for mineral wealth, the subjugation of the South, and the successful extract from its primitive rocks of the granite and basalt required to case the pyramid or mould into sarcophagi, and these blocks transported in vessels of reat size down the river at its highest flood or annual increase, to their destination. Civil and military requirements were met with careful organisation, and the sable races of Egypt's southern border drilled to expel the hostile tribes that infested its adjoining deserts. Since Ebers wrote three more pyramids of the Sakkarah group have been opened, and have revealed, by the details of their long inscriptions, that at the remote period of the VIth Dynasty the religious thought or belief in the circle of gods was as complete as at the close of its faith, of its polytheism. Pepi or Phiops, Merenra or Haremsaf, and Neferkara or Nephercheres had their costly sepulchres adorned with prayers and formulæ from the myth of Osiris, and direct declaration of the doctrine of the immortality of the soul.

The age of pyramids once past, and Egypt assumes another feature: the arts still improve, architecture rises to a higher conception. The temple surpasses the tomb at the time of the XIIth Dynasty, and the Doric column springs into life. The South is conquered for its gold and slaves; the North is advanced on for its mineral wealth; the Libyan or African wanders, as an itinerant juggler or a mercenary soldier, to Egypt. The Semitic families render obeisance to their Hamitic superiors, and enter Egypt as friends or vassals. The grasp which held the valleys of the Sinaitic peninsula retains it still more tightly, and Egyptian adventurers receive a lordly welcome at the court of Edom. The hereditary nobility are fostered by the Pharaohs of this and the subsequent line. Hydraulic engineering constructs vast reservoirs for irrigation, and the lake Mœris alone marks an era. The Labyrinth and the Obelisk, which attain a world renown, complete the circle of its civilisation, and are imitated by the other races of mankind. Literature still flourishes, religion retains its ancient features. From hence till the XVIIIth Dynasty there is a decline or an eclipse; but in the long interval, and towards its close, a new race of men—the so-called Shos, or Shepherds, Nomads, or Crossers — make their appearance. They seize the Delta, subdue the Egyptians, whom they drive back upon the swarthy Æthiopian. The ethnological relations of the Shepherd races are as obscure as the Egyptians. They resemble in type the Semitic; but some have endeavoured to connect them with the Hittites. Inferior in civilisation to the Egyptians, they adopted Egyptian arts, and their ascendency does not seem to have influenced in any remarkable degree Egyptian civilisation. The religion was also connected, through the god Set, with that of Egypt. At Tanis, their capital, are their remains; and the only distinctive marks of their rule is the appearance of the horse, which, brought from the plains of Asia, had probably contributed to the conquest of the valley of the Nile. Egypt expels the Shepherds, and a new native dynasty—the XVIIIth—surpasses the glories of those which preceded it. Thothmes III. defeats at Megiddo the combined hosts of Eastern Asia, and marches to the Euphrates. Nineveh and Babylon become his tributaries; and the world known to the Egyptians contributes its united wealth to the treasuries of the Temple of Amen. His sisters had already sent embassies and naval expeditions to the eastern coast of Africa. It is no longer an age of gigantic pyramids, but one of colossal temples. Thebes inflates to overwhelming proportions; stones and temples are piled on one another, and the statue of Amenophis III., lisping to the rising sun, adds another wonder to the list of Egyptian marvels. Subject to vicissitudes, religious animosities impair the extent of empire, the Delta falls into anarchy or foreign hands; but a new dynasty, itself of Semitic origin, wrests back the country, re-conquers Palestine, and breaks the strength of its great rival, the Khita, or supposed Hittites. One heroic figure—Rameses II., the Sesostris of Greek legends—stands out in the fierce glare of historic light. Poems and official inscriptions record his unwonted prowess, and his great battle of Kadesh, on the banks of the Orontes, restores the independence, if not the supremacy, of Egypt. The canal to join the two seas is commenced by his father, a long wall is built to resist the return of Asiatic hordes to Egypt. The Exodus takes place under his successor; and Egypt, now attacked by Libyans and other Mediterranean nations, victorious at the brunt, again relapses to another decadence, to be again restored to its pristine condition. After an intestine struggle, another Rameses III.—equally devoted to the life of the camp and the palace—drives off the invaders. From north and south, east and west, Libyans, Asiatics, Europeans, and negroes are all repelled. Thebes especially, the quarter of Medinat Habu, is embellished and increased. But here end the glories of the line; a long and inglorious suite of feeble successors led to sacerdotal usurpation. Assyria, emerging from its Western struggles, directs its attentions to the East, and in Egypt a dynasty with ambitious views and powerful armies marches its hosts into Palestine, under Shishakh, and pillaged Jerusalem. Henceforth possession of Egypt was alternately disputed. Assyria and Æthiopia, Sabaco and Tirhakah (B.C. 727) appear on the scene, to retreat before the victorious hosts of Nineveh; and when Assyria succumbs to Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar defeats Necho at Carchemish—Necho, who renews the attempt of the canal of Seti, and first endeavours to circumnavigate the continent of Africa. But Babylon has fallen to the Persian Cyrus, and Cambyses conquers Egypt (B.C. 527); the supremacy of Persia, shaken and contested for almost two centuries, is riveted, in B.C. 340, on the country, and the fall of Persia to the Greeks (B.C. 330) ends by the establishment of the Greek rule of the Ptolemies: the whole civilisation changes—arts, language, and organisations, are Hellenised. It is no longer Memphis or Thebes, but Alexandria, that is the capital; wealth accumulates, but men decay; the religion is not altogether effete, for splendid temples of inferior art are still erected, as evidences of a failing faith. Pedantic disputes and philosophic sophisms replace the mysterious dogmas of the old religion at the Court of the Ptolemies, and one monument alone—the Pharos or Light Tower—marks an addition to the progress of civilisation. The dramatic incidents of the ultimate fall of the Ptolemies, and the final conquest of Egypt by the Romans after the battle of Actium, are the story of a foreign race, and no magnificent ruins attest the Greek rule in Egypt. The Roman sway was a mere continuation of the Greek in its development. A superstitious veneration of Egyptian polytheism repaired or added to some of the older monuments, and built some newer temples, or continued those of the Ptolemies, but arts and sciences declined, and the rise of Christianity was the signal for the neglect or abolition of the devices of Paganism, without adorning the country with monuments of architecture or art, and subtle disputations on points of faith replaced Egyptian culture and Greek philosophy, while monks and hermits meditated in deserts political revolution, or the destruction of ancient edifices, and the Patriarchs of Alexandria consented to the pillage of its temples and its libraries.

But the conquest of Egypt by the Arabs in B.C. 630, although at first attended by destruction and disaster—owing to the religious fanaticism of the Mohammedan victors—gave an entirely new phase to the arts and sciences; and if sculpture disappeared, architecture took a new development. Manners, customs, and civil organisation, were all remodelled or absolutely changed. Under the Abbaside khalifs in the eighth century A.D. it had attained the highest grandeur during the reign of Haroun-er-Rashid, and continued still to develop under the rule of the Touloonide and Fatimite khalifs. The present work illustrates all this in the most striking manner, and exhibits all the peculiarities of Arab life and art—the marked influence in architecture which the pointed arch, in metallic products the damascened or inlaid work, in pottery the brilliant glazes, in the woof the embroidered garments, and in design the fantastic and interlaced patterns—exercised on the material civilisation of the West. The age of the khalifs was an age alike of poetry and romance, of enormous wealth and capricious prodigality to favourites, poets, and musicians, intermingled with vain ostentation, love of learning, and public oppression, which preceded the arrival of the Crusaders in the East, and their entrance into Egypt in A.D. 1217. These warriors, however, left no memorial more important of their advent than a rare and insignificant coinage struck at Damietta. This was, however, the age of Saladin, Richard Cœur de Lion, and Louis the Saint of France, and the termination of a vain enterprise of a rival fanaticism. The Sultans of the different dynasties have left, however, behind them magnificent mosques and splendid sepulchres, fallen into neglect and destined to ruin unless the interposition of public sentiment in Europe demands that they shall be preserved. The Turkish rule in Egypt, which began in the sixteenth century, had no great influence on the country, and collapsed under the rival intrigues of the Mamelukes and the Porte, but the French Expedition in 1798 renewed the old acquaintance with Egypt, which had been much impaired and almost lost since the first Crusade. For the conquest of Egypt by the French under Napoleon, the enlightened administration and scientific inquiry which accompanied the arms of France opened the eyes of Europe to the vast interest revealed by the oldest centre of human civilisation. All the ancient remains of Egypt were studied; those apparently most important were correctly engraved, and, for the first time, accompanied by scientific descriptions.

The French Expedition discovered the trilingual inscription known as the Rosetta Stone—the key to the interpretation of the hieroglyphs—and this monument enabled Young and Champollion to decipher and interpret the lost language of ancient Egypt, which, up to the beginning of the nineteenth century, had been laid aside as a problem apparently hopeless to solve, or taken up as a toy for the amusement of pedantry. The solution of the question in its fullest details by Champollion is one of the great literary discoveries of the century, and, when accomplished, astonishment and delight possessed all inquirers not inveterate in error or malignant by design, and a new charm pervaded every inscription, for the meaning, the age, and the object of which had been previously obscure, was rendered intelligible and plain. Religious history, manners, and customs, all were illustrated in a novel and surprising manner; the very walls, hitherto inarticulate, appeared to be endowed with speech. Stores of information contained in the various texts on the monuments, —mythological, historical, or explanatory—the speech of the noble and the exclamations and replies of slaves and peasants, were revealed. The papyri relating to the mythology, or the ritual to the funeral ceremonies, hymns to the gods, historical documents of all kinds, lists of monarchs, the epic poems of Pentaur in honour of Rameses II., the record of the donations of Rameses III. to the principal shrines of Egypt, an extensive literature and correspondence of scribes during the XIXth Dynasty, and earlier treatises on ethics, even works of fiction, sales, marriage contracts, and accounts, have, in consequence of the discovery, stood exposed to the eye, and form a new and extensive literature.* How much the charm of Ebers' work is enhanced by his deep acquaintance, not only with the monuments and works of art, but with their interpretation of them, and with all that has been said or written on the subject!

The modern period, from the ascension of Mohammed Ali in 1811, after the destruction of the Mamelukes, is distinguished by the plans of that ruler for the civilisation of the country on the European model, and the efforts of his successors to improve its prospects and attractions by excavations of the principal ruins, and the preservation of its antiquities by Saïd Pasha; the completion of the Suez Canal by Ismail Pasha, in 1869; the grand scheme of M. Ferdinand de Lesseps; and the extension of the limits of the country on its southern confines. The administration of its finances, and the consequent improvement of the country by the joint action of France and England, close the history of a period of nearly seven thousand years.

The modern Egyptians, the manners and customs of the different races, have been already described by Lane, Poole, Whately, Audouard, Goltz, Klunzinger, Zincke, and innumerable authors and travellers; and the personal experiences of Professor Ebers, besides his extensive knowledge of the principal authors in Arabic literature, have been added to the labours and remarks of his predecessors. His discovery of the ancient medical treatise of the old Pharaonic period, written in Hieratic, known as the Papyrus Ebers, and his scientific and philological works on Egypt and the books of Moses, hieroglyphical system of writing, in the “Zeitschrift fur Ægyptische Sprache” of Berlin, attest his researches into old Egypt; and his successful novels, “An Egyptian Princess,” besides “Homo Sum,” “Uarda,” and “The Sisters,” published in 1870, prove the power he possessed of popularising a subject hitherto deemed recondite. In the present work is the latest account of the Egyptians, for whom there will probably be a more brilliant future as civilisation advances, and more correct principles of political economy, and the importance of European civilisation as a means of political regeneration, become diffused in the far East. The interest offered by modern Egypt from all points of view, the comparison of its past and present condition, the striking difference between them and European costume and custom, receive a striking illustration from the aid afforded by photography and engraving, which give precision to descriptions however brilliantly animated or severely exact; and although Egypt, like the rest of the East, is intensely conservative, gradual change still insinuates itself, though rapid improvement lingers on its path.

It has been necessary in the English edition to add occasional notes to guide the reader as to the dates and other facts mentioned in the German text, which will thus receive illustration of points which might otherwise appear obscure; for although Egyptian chronology has been long debatable ground, and opinions on the remotest period vary to the extent of at least one-third of the whole chronology, history without some chronological indications presents only a hazy succession of events to the mind. In all cases, however, a probable date has been given, and even at the remotest period of the vast antiquity of the age of Pyramids the most recent discoveries tend to show the hoar antiquity and great age of these monuments, already preceded by a long duration of civilised human life and knowledge of arts and sciences. The importance of Egypt, both past and present, increases daily in the minds of Europe, as well as the conviction that it rivals with Greece and Rome, and shares with Assyria and Babylonia, the claims of attention to the past and future of the present day.

ANCIENT ALEXANDRIA.

WHOEVER arrives in Egypt, be he a native of the North or of the West, must first set foot on the soil of Alexandria. Weary of the long sea-voyage and of all the novel pictures that meet his eye in this strange quarter of the world, he retires to his night's rest, and closes his eyes to think of home.

Suddenly, a clear resounding song breaks the silence of the night; it is the Muezzin's call to prayer—the bell's chime of the East—nature having bestowed on man a tongue and tone fitted to rouse a response in the heart of every hearer.

The Muezzin sings out his benediction over the sleeping city in deep long-drawn tones. “Prayer is better than sleep,” he cries to the sleepless; and his voice rises to its highest pitch when he shouts with three-fold iteration: “There is no God but God!” or “Allah, Allah, Allah!” as introductory to a beautiful prayer.

Before rising from bed to make acquaintance with the Alexandria of to-day—the half-European threshold of the Nile valley—let us turn our minds to the past, and attempt in some degree to depict to ourselves the great Græco-Egyptian city, the most celebrated spot of later antiquity.

Alexandria, one of the youngest cities of the ancient world, was at the same time the largest and the most brilliant. The rate of its increase in extent, population, and commerce was in no way behind that of the greatest cities of the New World; and as regards the rapid development of the higher gifts of humanity— the arts and sciences—no American city even can offer anything approaching a parallel example.

Was it to its happily chosen situation that this great centre of learning and commerce owed its marvellously rapid growth? This is hardly evident at a first glance.

The northern coast of Egypt is flat, uniform, and unlovely, and though the waves of the Mediterranean sparkle in the sunshine in the harbour of Alexandria no less blue than on the orange-scented shores of Sorrento, or in the sunny bay of Malaga, they here break on many and dangerous rocks. In spite of the far-gleaming beacon of the Pharos of Ras-et-Teen, no vessel at the present day can enter the harbour of Alexandria by night.

An artificial canal begun by Mohammed Ali, the founder of the Vice-regal house, and named after the then reigning sultan the Mahmoudeeyeh Canal, washes the city precincts—but it is no branch of the Nile—and yields drinking water which could not be otherwise procured by digging wells, for from the soil of Egypt only salt springs rise. The coast in the vicinity of Alexandria, during the winter months, is beaten by storms of wind and rain; and the sky, whose pure azure is, at Cairo, rarely veiled, and then only by clouds that are dispersed in passing showers, is not less often obscured at Alexandria than in the peninsulas of southern Europe. Besides these drawbacks, the spot chosen by Alexander to be the site of a mart where the riches of Egypt might be exchanged for the treasures and marvels of the Indies, was at the extreme north-west of the Delta, equally remote from the Red Sea and from the high-road of the caravans by which Egypt and Syria held communication.

Nevertheless, the site selected by the genius and penetration of Alexander was the only one in Egypt which combined all the conditions indispensable to such a metropolis as he dreamed of, and such as, in fact, arose in fulfilment of his purpose.

A great Græco-Egyptian city, according to his idea, was to fill a double function; first, its harbour was to be a central mart both for the produce of the Nile valley and for goods imported from the south by way of the Red Sea, and these wares were to be dispersed throughout the world by the Greek merchants; while, in the second place, all the beauty of Hellenic life and culture in the new emporium was to be brought to bear upon Egypt. He had found the ancient realm of the Pharaohs still and stark as its mummied dead; in Alexandria the genius of the Greek was to find a new home, to release Egypt from the bonds of centuries, and to transform the barbarian nations of the Nile country, making them a controllable member of that mighty body of universal Greek dominion, which was the end he had proposed to himself as the goal of his heroic course.

On the eastern Egyptian coast lay the ancient harbours of Pelusium and Tanis on arms of the mouths of the Nile. He selected neither of these for the site of the new Greek city; for it did not escape his observant eye, or that of the scientific men who accompanied his armies, that the current of the Mediterranean bathing the Egyptian coast sets from west to east; and that, by carrying the alluvial earth annually brought down by the inundations of the Nile constantly eastward, it was destroying the harbours to the east of the delta.

How just was his foresight has since been proved; for at the present day, while thousands of ships crowd the quays of Alexandria, the ports of older fame—Pelusium and Ascalon, Tyre and Sidon—are choked by alluvial deposits, barred and useless.

In the year 332 B.C., Alexander laid the foundation of the new city, encouraged to the great work by dreams and omens which promised it a glorious future.

Directly opposite to the Egyptian port of Rhacotis to the north, close to the coast, lay the island of Pharos, of ancient fame; and behind the town, to the south, the Lake Mareotis, connected with the western arm of the Nile by an artificial canal which it would be easy to extend. The bay where the island lay offered ample space for many sea-going vessels, and thousands of Nile-boats could find room in the inland lake. A city rising between the two would be situated advantageously alike for imports and for exports, and Hellenic life would thrive and flourish unhindered; all the more because the Egyptian town on which it would be grafted was an insignificant one.

In Homer's Odyssey we find these lines:—

“A certain island call'd Pharos, that with the high-waved sea is wall'd, Just against Egypt … And this island bears a port most portly, where sea-passengers Put in still for fresh water.”

CHAPMAN.

These lines, it is said, were heard by the sleeping Alexander at Rhacotis, uttered by a venerable old man who appeared to him in a dream.

Orders were given for the measurement of the ground and foundations, and the architect Dinocrates was commissioned to prepare a plan. This took the form of a Greek peplum, or of a fan, and the work of indicating the direction to be followed by the roads, and the extent of the market-places, was begun by strewing white earth on the level ground. The supply of this material falling short, it was supplemented by the assistants of the architect taking the meal which had been provided in abundance for the labourers. The legend goes on to say that hardly had this been sprinkled on the soil when numbers of birds came flying down to feed on the welcome supply of food. Alexander hailed the appearance of these feathered guests as a favourable omen, signifying the rapid prosperity and future wealth of the city.

And in truth, as birds fly to corn, so, from all Hellas, enterprising immigrants sooncame streaming in; merchants and fugitives from Syria and Judæa, labourers and dealers from Egypt crowded to the new mart; and Alexander's distinguished general Ptolemy, the son of Lagus—who received the surname of Soter, or the preserver— fixed his magnificent residence there, first as governor and then as king. His talented successors, Philadelphus and Euergetes, not only did their utmost to promote the external power of Egypt, as well as its wealth and commerce, but strove eagerly to concentrate in Alexandria the culture and genius of their time; so that the learned men of the East and West crowded to the city, and learning and commerce vied with each other in the splendour of their bloom.

There is no city of antiquity of which we have such abundant records, and yet of which so few recognisable remains are left as of Alexandria. In vain we seek for an island opposite the city, although the little islet of Pharos does in fact still exist. The Ptolemies connected it with the mainland by a mole of quarried stone; and this huge mass of masonry was called the Hepta-stadion, from measuring seven stadia in length. It contained the aqueduct by which the island was supplied with water, and divided the harbour into two basins, which still exist. The Eastern, or New Harbour, which is no longer used, was in ancient times called the Great Harbour; the Western basin, in which the traveller from Europe disembarks, and which is being greatly extended by the Viceroy of Egypt, is now known as the Old Harbour, and in the time of the Greeks was called the Harbour of Eunostus, as it would seem after the son-in-law of Ptolemy Soter and Thais; this name, meaning “good return,” survived for a long period. The two communicated by channels that were bridged over; they have long since been closed up by mud and detritus, and a broad tongue of land has been formed by the falling in of the piers of the bridges erected by the hand of man, and by the pebbles and ruins flung upon them by the waves, supplemented by artificial

additions. Many houses of the modern Alexandrians stand on the ancient Heptastadion, and its soil is the first to be trodden by the newly-arrived stranger; for the largest of the western steamships cast anchor by its eastern quay.

The Pharos island now forms its northern point; it still bears a lighthouse, but this stands at the western angle, while the old renowned structure of Sostratus—which from its site was named “the Pharos,” and from which we to this day call a lighthouse a Pharos—stood at the opposite end of the island. It served to show the way into the rocky harbour, and was reckoned one of the most remarkable wonders of Alexandria and of the ancient world. It surpassed even the Pyramid of Cheops in height; but, thanks to the advanced state of science in our day, the light of the present lower tower shines out farther into the night than the beacon-fire which flared from the summit of its predecessor. Ptolemy Philadelphus caused it to be constructed of white marble by Sostratus of Cnidus, and he dedicated it to his deified parents. The famous architect carved his name, with an inscription, in the stone at the top of the tower. Over this, it is said, he spread plaster, and wrote on that the name of the royal builder or architect, so that when the more fragile material should have perished his own name might be read by future generations.

Let us now return to the mainland and seek the traces of the principal quarters, streets, and public buildings of the city.

By far the most magnificent portion was the Bruchium, bathed by the waters of the Great Harbour, and adjoining the oldest part of the city, namely, the original fishing port of Rhacotis. This old quarter was always the residence chiefly of Egyptians; and, as in all Egyptian cities, on its western side lay its “City of the Dead.” For, as the sun after its day's course sinks in the west, so the soul, after its life's course, found its rest there where spread the desert inimical to all life, and where the realm of death was supposed to lie. The colonists, following the example of the Egyptians, interred their dead there too, until late Christian times; and the traveller who at this day visits the neighbourhood of Pompey's Pillar, and wanders westward along the sea-shore, will come upon tombs hewn in the rock, and farther inland will find catacombs of considerable extent. Even in Alexandria the native Egyptian citizens had their dead embalmed, while the Greeks adhered to their national custom of cremation.

In the eastern part of the Bruchium dwelt the Jews; they had their own quarter, kept up but a slight connection with their brethren in Palestine, and at some periods exceeded in wealth and influence all the rest of the population, though at other times they suffered severely, and not altogether without fault on their part.

These quarters were connected by a maze of streets, in which riders and vehicles could move with comfort; they debouched on two main thoroughfares that crossed each other. The longer of these, running south-west and north-east, went from the City of the Dead to the Jews' quarter, and ended, eastwards, at the Canopic Gate— the Rosetta Gate of the present day; the other, cutting it at a right angle, led to the two gates of the Sun and Moon, and a layer of mould which has lately been discovered mingled with the pavement seems to indicate that both roads were ornamented with plantations. They must have been unusually broad and handsome. The vehicles of the rich, the loaded waggons, and the lordly processions on horseback which entered the city from the Hippodrome by the Canopic Gate, found ample room on the paved way of square granite, forty mètres broad; and when the sun was blazing hot, or when violent storms of rain fell, the pedestrian found shelter, for the wide side-paths were overarched by colonnades.

The gates of the Sun and Moon have vanished, the colonnades are overthrown, and recent layers of soil overlie the ancient pavement; however, the aqueducts under that pavement were, a few years ago, restored to their original purpose. Little remains of the houses of the inhabitants; yet the inquirer, if he quits the quarter occupied by the well-to-do Europeans, and betakes himself to the more modest Egyptian quarter on the western side of the city, and follows the line of the coast, or, passing through the Canopic Gate (the Rosetta Gate), walks across the open country, may come across many traces of ancient houses and public buildings. He has only to look round him. It is certainly vain to expect to discover monuments of any particular artistic merit; but he will find tanks of very early structure, traces of the foundation-walls of temples and palaces, thresholds, door-posts, and architraves in marble; in the mosques beautifully carved pillars from the Greek sanctuaries; a stone sarcophagus serving as a trough from which an ass quenches his thirst; the shaft of a pillar on which some Arab mother sits nursing her child, or which lies before a doorway, half covered with sand and overgrown with the herbs of the desert. The daily traffic of the Alexandrians was from the inner harbour by the Lake Mareotis to the sea and back again; on high festival days they betook themselves principally by the larger streets to the Bruchium. Here stood the Palaces of the kings with the Museum and its library, the noblest temples of the Greek gods, the Mausoleum called the Soma, containing the body of Alexander the Great, the circus and the theatre, the gymnasium, the Hippodrome with its winding course, and many other public buildings to which the principal officials, the learned and the artists, the freeborn youth, and the pleasure-seeking crowd constantly flocked.

Theocritus has given us a picture of the crowd on the day of the festival of Adonis, which two women—intimate acquaintance, and wives of citizens of Syracuse settled in Alexandria—have gone to assist at together. Gorgo and Praxinoa behave under the circumstances exactly as if they had been born in the nineteenth century after Christ instead of in the third century before.

Gorgo appears and Praxinoa orders her maid-servant:—

“Quick, Eunoa, find a chair, And fling a cushion on it.”

When Gorgo has taken her place and recovered her breath, she sighs out—

“Oh what a thing is spirit! Here I am, Praxinoa, safe at last from all that crowd And all those chariots—every street a mass Of boots and soldiers' jackets. Oh! the road Seemed endless, and you live so far away.”

Praxinoa laments over her “odious pest of a husband” who has taken this dwelling at the end of the world (probably near the Gate of the Sun). Gorgo warns her not, in her child's presence, to speak thus of its father, and Praxinoa calls out to the boy:—

“There, baby sweet, I never meant papa.”

But the small citizen is too sharp, and his “aunt” Gorgo says:—

“It understands, by 'r lady! dear papa!”

At last Praxinoa has completed her toilet with the help of the maid, who does not get through the business without a scolding, and Gorgo exclaims:—

“My dear, that full pelisse becomes you well. What did it stand you in, straight off the loom?”

To which her friend replies:—

“Don't ask me, Gorgo; two good pounds and more; Then I gave all my mind to trimming it.”

The smart lady then has her mantle thrown round her, her sun-shade elegantly put up, and when all is done she gives the child in charge of the nurse, desires her to call in the dog and to lock the door, and then hurries off with her friend, down the road towards the royal palace on the Bruchium. They get through the crowd unharmed as far as the palace gate, but there the mob and confusion are much greater, and Praxinoa cries out:—

“Your hand please, Gorgo, Eunoa, you Hold Eutychis—hold tight or you'll be lost. We'll enter in a body—hold us fast! Oh! dear, my muslin gown is torn in two, Gorgo, already! Pray, good gentleman, (And happiness be yours) respect my robe.”

The gentleman appealed to is gallant, and when they have reached their destination Eunoa says, laughing:—

“We're all in now, As quoth the goodman, and shut out his wife.”

We will follow the Syracusan ladies to the Bruchium and the king's palaces, which stood on the eastern side of the harbour, and eastward of the spot where Cleopatra's Needle lately stood, southwards from the peninsula of Lochias, which, however, can now hardly be recognised. Magnificent gardens surrounded the palaces of the Ptolemies, and adjoining them stood the most celebrated of all the institutions founded by the dynasty of the Lagidæ, the Museum with its library. If the Syracusan ladies had in fact come from the neighbourhood of the Gate of the Sun, they must have crossed the market-place, and thence have followed the Canopic way a little to the east; then they would have turned to the left by a side street, have passed the huge Circus of the amphitheatre—where tickets and programmes of the games to be performed would be offered them for sale, and horn or ivory passes for the performances at the festival. But Gorgo and Praxinoa resisted the temptation, and did not rest till they reached the grove of trees which was planted on the top of the artificial mound of Soma, the Mausoleum of Alexander.

The body of the great founder of the city had been already brought from Babylon by the first Ptolemy, and it remained in its golden sarcophagus till a degenerate son of the Lagidæ sacrilegiously melted down the metal and substituted a glass sarcophagus for the golden one.

The ladies went up by the citizens' steps, for the levelled way which led out from the palace through the Bruchium to the high streets might be used only by members of the court. It was called the “Royal Road,” and it was in reference to this that Euclid made the famous reply to Ptolemy Soter, who asked him for some easy method of attaining to a knowledge of his propositions—“There is no Royal Road to mathematics.”

The gymnasium to the right as they go on, is empty to-day, for all the youth of Alexandria are taking part in the festival; even in the courts and halls of the Museum, which for the present we will pass by, all is still; for the king has invited the most illustrious of those who dwell there to be his guests. Our Syracusan ladies are allowed to enter the vestibule of the palace, where the statue of Adonis lies on costly drapery spread on a silver framework, and surrounded by beds of flowers, and where the form of the lovely Cypris is to be seen on a not less magnificent couch. They are permitted to hear the festal song of the noble singer who was crowned mistress of song in the Ialemos the year before; but they have to hasten home, for Gorgo's husband has not yet broken his fast, and “without his supper,” says she, “Diocleides is simply vinegar.”

Just as the feast of Adonis tempted the two ladies to the Bruchium, so the greatest festival of the Alexandrians, the Feast of Dionysus, brought all the men to the palaces and their vicinity. This Feast of Dionysus was celebrated with even greater delights and tenfold more splendour than at Athens itself, though, no doubt, with less of the true sentiment of beauty. The Ptolemies made it the occasion for displaying the full extent of their wealth, and all the wild enjoyments of life and sensual desires that fermented and seethed in the souls of the excitable inhabitants of the metropolis of the world, at these feasts threw off all control, and rioted and revelled without restraint. Moderation was accounted a crime, and the Bruchium was the scene of a vast orgy.

Only a privileged few could share in the magnificent banquets within the precincts of the king's palaces; but every one was free to partake of the bounty bestowed on the people at the festal procession. The account of this feast as given by Callixenus, who was an eye-witness, sounds quite fabulous; nevertheless it must have some claim to be believed, even though it is allowable to make deductions from the numbers he gives. The representations given on this solemn occasion were connected with the myth of Dionysus, not however kept free from all admixture with Egyptian traditions and customs.

The procession with the mythological impersonations must have been interminably long. In the time of the native kings the ancestral images of the Egyptian gods and Pharaohs had been introduced; and in the same way the gods of Olympus with the Macedonian princes, Alexander the Great, Ptolemy Soter, and his son Philadelphus, were now represented. To add to the delights of the feast splendid sham fights were held, where the victors, and among them the king, received golden crowns as prizes. One such feast-day under the Ptolemies cost between £300,000 and £400,000; and how enormous must the sums have been which they expended on their fleet—eight hundred splendid Nile-boats lay in the inner harbour of the Lake Mareotis alone—on the army, on the court, on the Museum and the Library!

No sovereign house of that period could compare with the Lagidæ in wealth, nor have any kings ever applied their treasure to more profitable purposes than the first Ptolemies.

Ptolemy Soter, first as governor under Alexander and subsequently as king, was the founder of the splendid edifices on the Bruchium, many of which were only finished by his son Philadelphus. He expended but little on his own palace, for he was wont to say that a king should be lavish to others and not to himself. He was a frugal and at the same time a wise and powerful sovereign, who sowed the seeds of most of the learning, and laid the foundations of most of the institutions that afterwards made Alexandria great and famous; and his disposition to promote science and art was inherited even by the most worthless of his descendants. He followed Alexander's example in leaving to the Egyptians their old laws and gods; but he held them in subjection by establishing military colonies. He might even have succeeded in engrafting Hellenic life and the Greek spirit throughout the Nile valley if he had not denied all municipal rights to the children of mixed marriages, with a view of keeping the blood of the Greek colonists pure. Many as there were among the inhabitants of Alexandria who were not Greeks, the council was always addressed as “Men of Macedonia.”

Soter was equally zealous in the cause of commerce; he had the harbours of the city enlarged and improved; he brought eight thousand ship-builders from Phœnicia, and a great number of cedar trunks from Lebanon to use in increasing his fleet. The old Egyptian merchants had not known the use of a coinage, but had carried on their dealings by weighing out metal, which was commonly wrought into the form of rings. Ptolemy Soter followed the example set by the states of the Greek metropolis, and caused coins of gold, silver, and copper to be struck in Alexandria. Many of the Ptolemaic heads, particularly those on the more precious metals, are hardly surpassed in beauty of workmanship, and enable us to form a personal acquaintance, so to speak, with the different individuals of the family of the Lagidæ. The mathematician Euclid, the physicians Erasistratus and Herophilus, the Athenian Demetrius Phalereus, were among the circle of learned men which Soter gathered round him; Demetrius Phalereus he first took into his council as learned in law, and it was from him that the suggestion to collect a library afterwards emanated. He wrote a history of the wars of Alexander the Great, which is unfortunately lost to us. Among the artists who flourished under him in Alexandria, we need only name the painter Apelles and his rivals, and the sculptor Antiphilus. Buildings were needed in the new metropolis, pleasure and splendour were in great request in the great emporium of the products of three continents; what wonder then that Alexandria attracted artists of every description, that architects and pleasure-loving Greeks congregated there, that the East and West clasped hands there, the sovereign house setting the example of adorning life with all that was most lovely and delightful?

The hetaira Thais was Soter's first wife; his second was the Macedonian Berenice. Both these queens taught the Alexandrian ladies how the Greek feeling for beauty could be combined with the oriental love of splendour. The most exquisite of all the gems that have been handed down to us were engraved for the Ptolemies, and it was especially for the ladies of Alexandria that the weavers of Cos manufactured a delicate fabric of bombyx or silk, a kind of firm but transparent gauze, which covered without concealing the fair form of the wearer.

This is not the place to enlarge on the wars conducted by Ptolemy Soter. Towards the end of his reign, B.C. 284, he associated Philadelphus, his son by Berenice, in the government. This prince found Alexandria in an advanced state as to its structures, to which only the ornamentation was lacking—and nothing could more perfectly accord with his talents and tastes than the fulfilment of this task. A man of much smaller powers than his father, he would never have been equal to the effort of creating a great city out of nothingness; but the disciple of Straton and Philetas, the wealthy and tasteful patron of science, was eminently fitted to finish and elaborate that which lay under his hand. He and his father have been happily compared to Solomon and his father David.

Under him Alexandria reached the summit of its glory. No member of his family, with the exception of the last Cleopatra, earned a greater celebrity than he; and that not by the splendour of warlike deeds, but by the quiet arts of peace for which his reign of three-and-thirty years and an unheard-of influx of wealth gave him ample time and means. Under him was made that translation of the Bible into Greek which is known by the name of the Septuagint; but the story which tells of Seventy translators who, although they worked apart in different rooms, produced renderings which perfectly agreed, must be consigned to the class of legends.

The greatest and most valuable work of Ptolemy Philadelphus was his anxious care for the Museum, which under him attained its most flourishing development. In this magnificent structure the most distinguished sages of the time of the Ptolemies found a welcome, and such protection from external worries as conduced to their advantageous co-operation in study and in teaching. It was situated in the same quarter as the king's palace, and consisted of a “Grove,” i.e., a large court with fountains and arbours; an extensive open hall protected from the weather by a colonnade in which the learned met, disputed, and found room to gather their disciples around them; and a large building with a spacious dining-hall. Here the members of the institute reclined at their meals—for the Greeks always ate reclining—classed according to the schools to which they belonged; the Aristotelian reclining by the Aristotelian, the Platonist by Platonists. Each mess chose its principal (or president), and the body of principals constituted a senate whose sittings were presided over by a neutral High Priest chosen by the government.

The structure was spacious, the decoration of its courts and halls was splendid and artistic, and the independence of the individual sages appears to have been perfect; they were always at liberty to teach or to pursue their investigations in the quiet of seclusion.

In the time of Philadelphus the Museum was the focus which collected all the rays of the spiritual and intellectual life of the period, and the means of culture put at the disposal of its members were unequalled; for Philadelphus displayed so much judgment and liberality in extending the collection of books made by his father, and had it so admirably arranged and catalogued, that this library—which was in connection with the Museum of Alexandria, and contained four hundred thousand rolls—was justly regarded as the finest of all antiquity. By the time of Cæsar, when these treasures, which had guided the labours of many Alexandrian sages, fell a prey to fire, the collection begun by the Ptolemies seems to have increased to nine hundred thousand rolls.

There is no province of science which was not cultivated in the Museum of Alexandria, no branch of learning which was not promoted there; but the most important and permanent results were produced in the departments of grammar—philology in the modern sense of the word—and in natural sciences.