2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

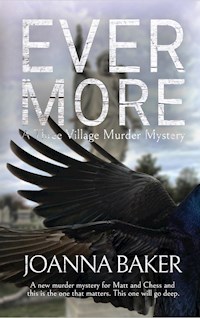

- Herausgeber: Soren Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

A

truth a little girl can’t bear to remember.

Emerging in dreams.

Dream Five

My mother starts turning. And now I don’t want to see her, because she is already dead. I shout, ‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry.’ But my mother turns and the hat flies off and soon I will see her face and now I am screaming.

This is Matt and Chess’s third gripping murder mystery and this is the one that matters. This one will go deep.

Chess Febey’s mother died when she was five and no one will tell her how or where it happened.

But when she hears the word

evermore, she immediately knows two things: that word has something to do with her mother … and she must find out the truth.

Chess knows there are memories somewhere, waiting, just beyond her grasp. And they’re emerging in her dreams.

But when Chess and her friend Matt Tingle finally discover the story of her mother’s death, it is more terrible than anyone had imagined.

Matt and Chess’s third mystery is a story about love. It is about lies and cruelty, sudden death, tragic loss and deep deep anger.

And a truth a little girl can’t bear to remember.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Devastation Road

The Elsinore Vanish

Acknowledgements

Evermore

Joanna Baker

Copyright © 2022 Joanna Baker

All rights reserved.

Published by Soren Press, Lindisfarne, Tasmania.

Cover design: Pat Naoum of Red Tally.

ISBN: 123456789

ISBN-13:123456789

In loving memory of Dotti Simmons.

We miss you.

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

From ‘Sudden Light’

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Prologue

Dear Matt,

You can read the dream journal now. Start at Dream Five. I think you’ll be shocked.

Because now I can see I knew the truth even when I was a little girl.

And that means the whole stupid investigation thing we did was just a waste of energy. We did all that charging around. We hurt people. We hurt ourselves. When all we really had to do was sit still and read.

Of course, in dreams the truth is twisted and disguised. Dreams are like riddles. It’s never obvious what they mean.

But we should have looked more closely. Because all the clues we needed – all the terrible truths we worked so hard to find – they were there for us the whole time, in the dreams.

Chess.

(PS Oh and remember I used to be called Jessie. But please never use that name now. It makes me feel a bit sick.)

Chess Febey: Dream Journal

Dream Five.

I’m standing at the end of a shadowy room, pressing my hands against a window. Behind me is some kind of museum — a lot of lumpy things covered in cloths. Outside I can see a stone terrace, a swimming pool and a tiny shelter shaped like a Swiss mountain hut. The sky is glowing greenish-blue and there’s a large orange moon.

My mother is standing on the terrace with her back to me. She’s wearing an enormous hat so I can’t see her head or her hair. Her long green dress floats around as if she has no legs. She is looking at the moon.

Behind me a voice says, ‘Come here Jessie.’

The water in the pool is swirling. It looks like blue paint. It is dangerous. I want to warn my mother. I try shouting, but no sound comes out.

I start banging on the window. My mother can’t hear me. I want her to turn around so I can tell her about the danger. But I also dread that when she does turn around, something terrible will happen.

I hear sounds of a party somewhere in the distance – laughter, the clink of glasses. The voice says, ‘I’ve always known.’

My mother starts to turn.

And now I don’t want to see her because she is already dead.

I want her to stop. I shout. ‘I’m sorry! I’m sorry!’

But she won’t stop. My mother turns and the hat flies off and the green dress swirls and her black hair flies out and soon I will see her face and now I am screaming.

Chapter 1

Evermore.

That’s how stupid it was – just that one word. Chess heard it in a Christmas carol, and I saw her hearing it. And when I saw her expression, I knew something was going to happen and I knew it was going to be big.

Chess and I could recognise trouble when we saw it. We’d had a fair bit of trouble in the last few years.

No, that’s a weak way of putting it. Chess had been burned and bashed and terrified, and I’d been bashed and terrified and had two ribs broken, and we’d caught a couple of murderers. It was stunningly, amazingly bad and I’ve had to talk about it to a lot of people. I’m pretty much done with describing it all now and you can read about it in other places.

But there is one thing I want to put in here. When we were dealing with the last murder, the one in Beechworth last September, we were stupidly innocent. We thought we were Matt Tingle and Chess Febey, experienced investigators, helping people, making the world a better place. And I remember saying that when it started I had no idea how bad it was going to be.

Well this time – the time that began with Evermore – this time I didknow it was going to be bad. I knew it as soon as I heard the word and saw Chess’s face. It just came to me – that everything we had done up until this point was a kind of preparation. Something was starting, and this was the one that mattered. This one would go deep.

The other thing I need to say at the start is that, after everything that’s happened to us, Chess and I have changed. Chess has grown out her fringe. She’s become quiet and less blank – she shows more emotion than she used to. And people tell me I’m nervy and irritable. Could be true. And I’m more chattery. Is that a word? I chatter. The point is, anything could’ve started us off on this next problem because we were primed for it.

In the end, it was set off by the word ‘evermore’.

Chess and I were at one of those things we’ve been to a thousand times – the Yackandandah Carols by Candlelight in the Major Johnson Buckford Memorial Garden. We’d been dragged there by my parents, because there was this kid staying with us … Doesn’t matter. We were keeping a kid happy, that’s all. Plus, my parents were trying to keep Chess and me busy. We were starting to go better at school again and have some normal conversations, but we were still a work in progress. So for the Christmas holidays, we were supposed to do a lot of normal stuff, get out and about, participate in the community, look happy, look like everyone else. We were supposed to look as if our scars weren’t hurting.

So there we were, at ten o’clock at night on the Thursday before Christmas, holding little candles with plastic cups around them and smiling up at the public school choir, all decked out in bright green onesies, on the old bandstand. Chess and I were singing away, trying not to look past the stage into the shadows, reading the words, remembering the choruses, nodding our heads around to show how into it we were.

I’d found two things that would help me survive the night. First, the choir master’s red waistcoat was so tight it looked as if it was making his eyes bulge. Once I’d noticed that, I could keep going back to it for another laugh. Second, Troy and Mikaela Twomey’s plastic battery-operated candles, with their long white tubes and triangular heads, looked like … who’s reading this? … I’m going to say ‘penises’ even though that’s more embarrassing than just about any other word for the things. But yes, the fake candles looked like penises and I didn’t know why everyone couldn’t see it. So that and the conductor’s waistcoat were little gifts I was holding onto to get me through the night. And I was going well. I joined in the swaying. I even contemplated putting my hands up and waving them from side to side.

Then we got to that ‘Hark Now Hear’ carol. Chess wasn’t really singing. She was looking over at Sophie Benson and her boyfriend, who had their arms around each other, and at Sophie’s ex who was watching them with his teeth clenched, which is normal for her. Chess, I mean. She studies people.

But then we got to that word ‘evermore’ and I saw her stiffen. She frowned down at the song sheet and went pale, and I knew immediately that our normal act had been for nothing. When the chorus came around a second time, Chess’s mouth lost its shape. I had no idea what was going on but as we sang the word, she just stared at me. And whatever evermore is – whatever eternity is – I felt we were never going to get there, because time had just stood still.

And then nothing happened. For three months. Chess went very quiet but no one noticed. Or if they did, they just thought it was because of the three murders we’d been involved in, or because of her depressing life, or because that’s just the way she was. But I knew it was more than that.

Since the carols, Chess hadn’t been sleeping well. I tried talking to her about it but she said she was fine. She was getting thinner. Her arms looked like little puppet sticks, the way they used to when she was little. And her face was puffy and greyish. She was starting to look like Wednesday Addams.

I knew how this went. Chess was worried about something. She didn’t feel like talking about it yet, but at some point I’d end up being involved. So I made sure I spent a lot of time with her and waited.

Outwardly nothing happened. We started Year Eleven and just got on with things.

Then, on a Friday night in the holidays before Easter, she had a second silent freak-out. We were looking after that same kid, the kid who doesn’t matter (OK, who does matter, because yes, Mum, everybody matters, but who doesn’t matter for this story). The Yack Theatre Company was putting on a pantomime to raise money for the community veggie garden and we took him to that. Yep, we really showed this kid the heights. The pantomime was called Goldilocks, but that also doesn’t matter.

The significant thing is the moon.

In the pantomime the bears’ kitchen had a window with a curtain over it. We sat through the porridge serving and going for the walk, through the bit where Goldilocks comes in, and through all the fooling around with the audience screaming ‘He’s behind you!’ and a lot of other stuff. Then halfway through the show – at about scene 153, by the feel of it – it became night and the window was suddenly lit up from behind by this yellow moon and the orange curtains started glowing.

As soon as she saw that, Chess stood up. Not in the stoopy, apologetic way of someone who has to go to the loo or something – she just rose up out of her seat and stood up straight.

That’s all she did, but in the middle of a darkened, kid-wriggling, lolly-rustling theatre it was enough, if you know what I mean.

No one said anything. The lady behind her coughed politely and whispered, ‘Excuse me, dear’, and Chess snapped out of it and sat back down again.

But after the theatre, Chess said she needed to talk. Her face was just like it had been at the carols and I knew this wasn’t over, that it wasn’t ever going to be truly over.

I also knew that I was in for a session.

Chess and I have had a lot of sessions, partly because she’s been half living with us for nine years now, but mostly because of what we’ve been through. I don’t know how to describe it exactly. I’m going to say we’re bonded. We feel we know things about the world and about ourselves that other people will never know. When it’s just the two of us, we can say anything without worrying about how pathetic it sounds. And we have a lot of stuff to unload – nightmares, and being afraid, and worrying about death. We’ve got to the point where our thoughts feel almost as if we’re both having them.

So that’s how I knew what this session was going to be about.

Chess’s mother left home when Chess was three and went overseas somewhere – Italy, I think. And she died when Chess was five, which was awful and tragic and everything, but it’s even more tragic – bizarre, even – because no one will tell Chess how her mother died. Up until now she would never allow herself to care about it. But like I said, we’ve changed, and now she did care. Chess’s mother had died and she didn’t know where or when or why or how. Her own mother.

So that’s pretty major. I think I’d always known it would come up one day, as a thing. And here it was.

After the pantomime, in my bedroom … Can I just say here that Chess isn’t like other people? Her explanations can be a bit out there, and if you want to get even halfway towards understanding her, you just have to relax and let it flow past you. And never ask questions because that definitely makes it worse. I was experienced at this now. I wondered why she would stand up in the middle of a pantomime and why the word ‘evermore’ upset her, and I knew the answers to these questions were important. I also knew the best thing was to sit back on my cushions and let her talk.

This is the explanation she gave me.

She’d been reading about the history of the universe. Yes I know. But I’ll try to condense it. Big Bang, evolution, wars, iPhones. And soon there’ll be the future – environmental damage, a meteor, the end of mankind, the death of the sun, dark energy and a Big Black Hole that sucks it all away again.

Yes, Chess had been thinking about time, and she’d ended up with this idea that you’re connected back to things by your parents and their parents and their parents before them, right back to fossils and primeval slime. And her point was that whatever had been and whatever will be, she won’t be a part of it. Not until she finds out how she fits into it, which means finding out where she came from, which is her mother.

Hence the evermore connection.

Did I say ‘hence’? I spend too much time with her, I really do.

It went on and on. And if there’s one thing Chess and I found out from dealing with two murders, it’s that I’m not a hero. And if I ever had a scrap of hero-ness it’s completely worn out. So after a while I was tossing around in the cushions groaning, and by the end I was kind of roaring at her.

But Chess is used to me. Back in the old days, last year, if I was mad at her she used to withdraw into a quiet little shell. But some of her old personality might have been worn away too. Because this time she just looked at me blankly and said, ‘You know you’re going to end up helping me, so why don’t we just skip this bit and get on with it?’

Chess had made up a lot of stuff to explain what was bothering her, but really it was simpler than she thought. For some reason, the word ‘evermore’ and the orange curtain and the moon had reminded her of her mother. She’d been wondering about her mother all her life, and those three things had acted as a … that thing that starts things off … and now she wanted to find out everything she could.

She only had weak memories of her mother. She remembered a high laugh and floaty hair and blue nail polish. Now she wanted to know more. A lot more. Everything.

Most of all, she wanted to know how her mother had died.

Lena. Chess’s mother was called Lena. Chess never used that name. She called her father ‘Alec’. But she never said ‘Lena’. She also never said ‘Mum’ or any other name. She only ever said ‘my mother’. I don’t think she even realised. I thought I should talk to her about it. But now wasn’t the time.

Catalyst. That’s the word.

When she got home that night, Chess asked her father about her mother’s death. She probably insisted a lot more than she had in the past, but Alec just stormed out of the house. He is an alcoholic who was nice to Chess when she was little but now spends a lot of time away from home and hardly ever talks to her. Her mother’s parents are dead. Alec’s parents live in Ukraine and Chess has never met them. She didn’t really have anyone else. She had me.

So the next morning she texted me and I went around and we talked it over. Again.

She looked tired, and she was intense in the way she sometimes gets, but she was OK. We decided things pretty quickly. This was important to her and it wasn’t going away. We’d investigated three deaths now and we could investigate this one. It had happened a long time ago and we didn’t have anyone who would talk to us about it. That left us with only three clues.

They weren’t much.

The word ‘evermore’, an orange curtain and the moon.

Chapter 2

‘No. It’s too weird.’ I put Chess’s book on the table and pushed it towards her. ‘A dream journal? Who even keeps such a thing?’

I wanted to say that she was sixteen, not seven. Instead I got up and went to the kitchen bench.

After we’d agreed to investigate Lena’s death, we’d immediately started getting stuff out of Chess’s fridge. It’s one of the few things we agree on. Big decisions require celebrating. Chess is good at shopping. She had wraps, felafels, hummus, tzatziki, and a pot of tabouli. We lined it all up and I got out two plates. But before I could get into it, she wanted me to sit down and read her dream journal.

‘Why would you write all this?’

‘You’ve been writing a lot.’

‘Yes but real things. What happened to us. Our mysteries. That’s a record for other people, to help them understand what’s wrong with us. This is just …’ I stopped myself before I said ‘insanity’. Chess is sensitive about that word.

‘So you’re a real writer?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

Chess picked up the journal.

‘Your writing is therapeutic. That’s why you do it. And this is the same. But that’s not why I asked you to look at it. I think it’s important to our new quest.’

Quest. That’s actually what she called it. I laughed, but she was dead serious. She held the journal out again, asking me to have another go.

‘Maybe you can just tell me.’

I handed her a felafel and she wolfed it down without noticing. Then I made two wraps and let her talk.

‘I have dreams. I mean a certain kind of dream. I’ve had them since I was little. Lately they’ve become more frequent. There are a few different ones, but I know they’re related, because they all feel the same. I think they mean something.’

‘Chess you know I don’t go for this teen-witch stuff.’

‘Well me neither. Obviously. But these dreams feel important. They always have. They have one thing in common and that is that I’m always afraid.’

‘So they’re nightmares.’

‘Not just ordinarily afraid. They leave me with a kind of deep … I don’t know how to explain it. I lie rigid in bed, breathing fast. Panting. It’s as if I’m afraid … you know …’ She really didn’t know how to explain it. ‘… in my heart.’

I stopped rolling wraps and looked at her. She was pale. Her skin looked sticky and her eyes were sunken.

Chess and I had been damaged by what happened to us. We’d learnt to ask if the other was OK. And we had an unspoken agreement that we would listen carefully to the answer.

I said, ‘Afraid. In the dream and then afterwards. In your heart?’

Chess looked relieved that I was finally paying attention. ‘In all my dreams I’m searching for my mother. Sometimes she looks like a blackbird, but it’s always her. She needs to tell me something and I can never find out what it is. Things get in the way. Or I need to tell her something and she can’t hear me.

‘When I wake up, I have the sense that I’ve missed something important. There’s something I need to know, hidden in the dream. So I try to remember them in as much detail as I can. But I can never work out what the important thing was.’

I didn’t have anything to add at this point. I took the wraps to the table.

Chess said, ‘I’ve come to see there’s more to understanding reality than simple linear logic. There are thoughts we’re not quite aware of, and knowledge that is hard to reach.’

I nodded, my mouth full.

‘So, if we’re going to find out the story of my mother’s death, I’m saying the dreams have something to do with it.’

I shrugged and nodded again.

‘Anyway, I have to read you this one about the dream I had last night. Something happened after it and you won’t understand how I felt about that unless you hear the dream.’

I swallowed.

‘OK.’

She looked at me, then started reading.

I’m standing at the bottom of a muddy road. The air is brown. Weird and thick. The ground is waterlogged and poisoned, with a few bits of dead grass. There’s an oily lake. I know the lake is evil, and I know that the evil is connected to me in some way.

At the top of the road is a house. The house is low and grey and forbidding and I am full of dread. But there is a secret inside and I have to hear it.

I am now at the house. I can hear someone whispering but I can’t hear the words. I go inside and the whispering stops.

I am in a corridor lined with doors. I push one open and hear the whispering again. As I enter the room, a door in the opposite wall closes and the whispering stops.

I know they are watching me.

In the next room the same thing happens. Whispering, a moving shape, a door closes, then silence.

In the third room, there’s a window with curtains. The curtains have orange spots that are drifting around as if they are made of water.

A voice whispers, ‘Evermore.’

In the window there is a blackbird sitting on a railing. I have to ask the blackbird what the secret is. I run up to it but instead of asking a question I start screaming and crying.

I’ve frightened the blackbird. It tries to fly, but instead it falls out of sight, suddenly, like a stone.

‘That’s it?’

It sounded ruder than I meant. Dreams just feel like bullshit to me. But I wasn’t going to say that.

Chess said, ‘A dream isn’t a story. They don’t have a form or a neat end.’

‘Hmm.’

Chess was serious about this. More than serious. Her eyes were wet and hot.

I put a hand on her shoulder. ‘Nightmares are the worst.’

‘I woke up full of fear and … it was a kind of horrible … hopelessness. I was stiff and panting. I lay there for ages, trying to force myself back into the real world. And that’s when the thing happened that made it much worse.’

I put my wrap down and waited.

‘I was still in the dream. It wasn’t just the feeling. The whispering was still there too. There were angry hissing voices outside my bedroom window. I can’t tell you how bad that was. I put my pillow over my head and then looked out sideways at the window. I was petrified. It wasn’t rational.’

I grunted a laugh.

‘But I gradually got a grip on myself. I told myself I had really heard that whispering and that was why it had been in my dream. The sound had penetrated my sleep, the way an alarm clock does. Unfortunately that idea didn’t help much.

‘Then one of the whispering voices said, “… the man who died.”’

‘Oooh. Hang on. The man who died?’

‘I wasn’t sure if I heard that or imagined it. There was a dim light around the edges of the curtains. I struggled up and sat on the edge of the bed straining to hear. I looked at my phone. It was half past midnight. The voices started moving away, down the front path. I stood up, but then I couldn’t move. I just stood in the middle of the room. I could hear the voices hissing at each other. Two people having a kind of whispered argument. Then, right at the end, I heard a voice say clearly: “It’s going to happen, Alec. We need to get ready.”

‘Suddenly I found I could move. I went to the window and lifted the curtain a little bit. Alec was there, just inside our hedge. He said, “Paddy, I’ll ring you.” And moving away through the gate was a shape. I had the impression of an oldish woman in loose clothes, and for an instant I thought I knew her. But she vanished before I could see her properly. And that was awful because it was like the dream.’

‘Oh Chess.’

‘It was just a coincidence. My mind was drawing false connections. It just upset me, that’s all.’

I put a hand on her hand. She turned hers over and gripped mine. We’d come a long way.

She said, ‘But sometimes irrational things are important.’

‘They are, Chess. They are.’

Chapter 3

I don’t like what we did next. I tell myself we didn’t have any choice, but I’m not sure if that’s true. We justified it by thinking that Alec had a responsibility to talk to Chess about her mother and he was refusing to do it. And he was caught up in something about a man who died. And he was a drunken bastard who didn’t care about his daughter.

He should have cared. He should have been able to see how much Chess needed to find out everything she could about her mother. She needed to fill out her little-girl memories, hear from people who’d known Lena. Find out what sort of person she’d been. And she needed to find out how Lena had died.

With Alec not talking, and with our three pathetic clues, Chess could only think of one way to start. She said we needed to go back through all her childhood stuff. Maybe something would trigger a memory.

‘One lucky thing – at our old place Alec had his study in a shed, a long way from the house. So, when our house burnt down, that stuff was still OK. Now I need to look through it.’

I said, ‘What kind of stuff, exactly? Old toys and things?’

‘Why not toys?’ I’d touched some kind of nerve. ‘Toys and picture books might spark something. I used to have a music box. But there’ll also be paintings I did when I was small. There should be a few letters she wrote me, I think, or maybe they’re just drawings and birthday cards. And there must be photos. I haven’t seen any of it since I was little.’

‘Not even photos?’

‘No. He keeps it all in a big black trunk under his writing desk.’

‘Why?’

‘He said it would be safe there.’ Chess frowned. ‘But now he won’t let me open it. I can’t remember exactly when he told me that, so I must have been very young. But I’m not allowed to look at the old things. It’s something I’ve always known.’

‘That’s weird.’

‘Obviously.’

‘And a bit creepy.’

‘Yes.’

‘And he definitely won’t talk about it?’

Chess gave a sour laugh.

‘Yeah, all right.’ Alec was stubborn and unreasonable, and if he didn’t like your questions he flew into rages.

But I’m still not sure if it justifies what we did.

We broke into Alec’s study.

And yeah, I know after that build-up you’re probably going ‘Pffft’ and thinking ‘big deal’.

But it was a big deal. To understand, you’d have to know what their life was like.

Chess always defended Alec to other people, but he was moody. His anger was never too far from the surface. Also, he was an alcoholic who was always trying to avoid alcohol, but every couple of months he’d disappear and stay with friends and they would drink the whole time. Then he’d come back, dirty and drunk, and my parents would help him get sober. And when he was sober, he looked sick and got moody again.

He never hurt Chess, but he never looked after her either. She looked after him. That’s something she’s taught me, really. You might not like your parents, but you can’t help loving them. She spent a lot of time at our place, but she was determined to keep a home with Alec.

A few years ago their house had burnt down, but they found another one, just as cheap and even more derelict. It was made of grey boards with a few smears of creamy paint left over from years ago. The roof had holes covered with bits of loose iron that flapped in the wind. The front windows had shredded canvas awnings. There was a poky little porch with rusted railings that came off in your hand if you touched them. I know that because it happened to me.

Chess had taken over the inside and that was pretty miraculous. She had chosen a picture out of a magazine in the library – just one picture, because she really wasn’t into this kind of thing – and copied that. She had pulled up all the lino and carpet and scrubbed the dark floorboards and then painted every wall white – except for a few holes where the plaster had fallen off, showing wooden slats. She had bought bits of white lace in op shops and hung it in every window. It threw soft light into the rooms. All the furniture had been given to them, so it was completely random, but it actually looked OK against the white walls and the dark floor.

Chess’s house was clean and a nice place to be.

I’d never seen Alec’s study. He kept the door locked. It was some big deal for him. He used to be a journalist and he still wrote things and occasionally sold them – articles about history and book reviews, I think. Once he said he was writing a novel. He hid away in his study for hours. Chess had been in there a few times, but she wasn’t welcomed. No one else ever went in. Alec was sensitive about it.

So yes, breaking into that study was a serious invasion.

It wasn’t hard to get in. Alec had gone out early, and he usually had lunch with a friend in Myrtleford on Saturdays. Chess was pretty confident he wouldn’t be back for a while. She had a piece of wire and picked the lock in about two seconds. She learns a lot of things from YouTube.

The study was like the dark negative of the rest of the house. It was cluttered and stuffy and it smelled of sour wine and dust and something like old cheese.

Chess said, ‘Have a good look at all of this.’

At first I thought she was complaining about the mess. But she didn’t look disgusted. She was looking carefully around the room.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Look at the details. There’ll be a clue.’

I didn’t know what she was talking about, but I knew this was a big experience for her, so I did what I was told and looked around at the room.

In the middle there was an Asian-looking rug. You could only see a small part of it, because the place was crowded with a couch and an armchair, random tables and chairs, and three desks. Above the desks there were bookshelves. Every surface was stacked with stuff – books and papers, of course, but also boxes and postage tubes and arty looking magazines. There were a lot of pictures in frames, one or two on the walls, most just leaning against things.

On one desk, propped against a bookcase, was a picture that looked like an old-fashioned playing card, blown up large – a creepy looking face with a hooked nose, wearing jewelled clothes and a crown. It had the letter ‘K’ on it. Crammed among all the books and pictures was a lot of random stuff – a clock, a model of a building, a beanie, a pink pot with a flamingo head, two enormous stuffed birds, a flute and a piece of driftwood. On the floor, leaning up against a chair, was a pin board covered in sketches and diagrams. And there was assorted junk scattered around in corners – a metre-high world globe, an old leather satchel and a neon sign, lit up, that said ‘Acorn’ in purple letters.

It was the kind of place where you’d never find anything, the kind of place where even the thought of looking for something made you feel depressed. Also, the mess felt personal. It was a room to be ashamed of. I wanted to get out as quickly as we could.

I said, ‘So the trunk is under something?’

Chess was over at one of the desks. She moved a laptop, lifted a pile of papers and pulled out a photograph in a frame. ‘I found this years ago. He doesn’t know.’

The photo showed three women standing in a kitchen.

‘Is that …?’

‘This one.’

Chess stabbed a finger at the blonde woman in the middle. That was her mother. Lena.

‘Oh.’ I tried to sound pleased. ‘Wow.’

‘I got it out once. There’s nothing on the back to say where it was taken or who the other people are.’

Her voice was cold and flat. She pressed the photo against her thigh. She wasn’t ready to look into her mother’s face. I guessed that would bring up some strong emotions and that would slow her down. And we had a job to do.

‘So where’s the trunk?’

Chess put the photo face up on the main desk. She reached underneath and pulled out a pile of magazines called The New Yorker and a cardboard box filled with papers. Behind them was a trunk. ‘Trunk’ was exactly the right word for it. It was like something out of a pirate movie. Black with wooden bits going around it and a big metal keyhole. The classic treasure chest.

Chess moved her hands across the lid as if she was patting an old pet. Then she stared at it. ‘The trouble is, we need the key.’

‘Do you need a key? Can’t you …?’ I wiggled my finger miming her trick with the wire.

‘No.’

From the definite way she said it, I knew she had tried.

‘OK. I’m guessing you know where the key is, then?’

‘He left me a clue.’

‘A what?’

‘I was very young when he told me. He probably thinks I’ve forgotten. He said he didn’t want me to open the box until I was ready, so he hid the key. He said it would be hard to find by just searching.’

I waved a hand at the mess in the room. ‘Ya think?’

‘But just in case he die … Just in case he disappeared or something, he didn’t want me to have lost my stuff forever. So he left me a clue about how to find it.’

‘That doesn’t make sense. Did he want you to find it or didn’t he?’

‘You know Alec.’

What she meant was, a lot of what Alec did was illogical and bizarre.

But, in a way, this also fitted. Chess and Alec both liked puzzles. It’s about the only thing they shared. When he was in a good mood, they did crosswords together. When she was younger, he used to set her word games and little treasure hunts with clues, and not just at Easter. I tried to help once. I followed Chess around, watching her solve the clues and then I shared in the prize lollies. Alec had tried a few word games on me over the years, but I was always a disappointment.

Chess was standing very still, staring at the photograph of her mother. I needed to keep her focused.

‘So where’s the clue?’

‘In the land of the blind.’