Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

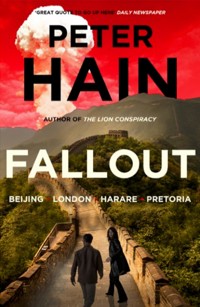

An explosive Cold War thriller, a deadly arms race that threatens to tip the world into conflict. South Africa, Zimbabwe, China and Britain. In the shadow of the Cold War, a deadly secret connects three continents, and time is running out. When a mild-mannered scientist accidentally uncovers a web of international espionage during a routine visit to Beijing, he's thrust into a deadly game of cat and mouse. His only ally? A magnetic anti-apartheid activist who may have secrets of her own. As they race to expose the truth, a veteran South African intelligence operative moves through the streets of newly-independent Zimbabwe, his mission intertwined with the machinations of a mysterious Chinese power player from Mao's inner circle. Meanwhile, a sinister collaboration between apartheid forces and rogue British intelligence agents works in the shadows to keep their nuclear conspiracy buried, at any cost. From the neon lit backstreets of Beijing to the wild, untamed lowveld where Zimbabwe meets South Africa, this explosive thriller weaves together Cold War tensions, political intrigue, and the threat of nuclear devastation. As these disparate threads converge, our unlikely heroes find themselves at the centre of a plot that could reshape the balance of power in the Southern Hemisphere, if they can survive long enough to expose it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

FALLOUT

Beijing, London, Harare, Pretoria

Peter Hain

iv

v

For those who bravely waged freedom struggles against apartheid South Africa and racist Rhodesia – and the equally brave human rights activists in modern China.

Also, for those who have not betrayed the inspiring values of such struggles.vi

Contents

Characters

Amir Bhajee – ANC official in Harare

Ruth Brown – Jenny’s radical aunt

Jannie Craven – young South African activist

Florence Dube – deputy Zimbabwe security chief

Jim Evans – British nuclear physics professor

Jonathan Fletcher – Green Planet headquarters official

André Geffen – Captain in Zimbabwe Air Force

Simon Jeffries – British ‘Noted Person Delegation’ member

George Kasinga – ANC chief in London

Thabo Kumalo – South African miners’ leader

Oliver Magano – ANC’s man in Lusaka

Major Keith Makuyana – Zimbabwe security chief

Selby Mngadi – senior in ANC’s military wing, MK

Stan Moyo – Zimbabwe President’s security chief

Moses Msimang – ANC official in Harare

Ed Mugadza – deputy Zimbabwe security chief

Wang Bi Nan – senior Chinese ministerial aide

George Petersen – ANC official in Harare

Shu Li Ping – official interpreter

Hu Shao Ping – Chinese student

Dick Sewell – Green Planet activist viii

Jenny Stuart – British political activist

Captain Mauritz Swanepoel – veteran apartheid assassin

Lesley Stapleton – Jenny’s activist friend

Robert Temba – ANC chief in Harare

Venter and Coetzee – apartheid assassins

Jan Viljoen – apartheid agent

Harold Williams – member of ‘Noted Persons’ delegation

Jimmy Wentzel – South African human rights lawyer

General KJ van der Walt – head of apartheid intelligence and security

Prologue

The cold, cruel wind had howled unremittingly all night across the lowveld, penetrating everything.

Finally, a sliver of sun peeked over the horizon, seemed to think better of it, and settled back.

A dassiesurfaced, sniffed, twitched, then scampered down its burrow.

An owl, beacon-like eyes swivelling, watched and waited, knowing its hunting time would be over when darkness ended.

But inside, the prisoner had lost all sense of night and day.

The relentless bright light had seen to that. Whichever way he turned, or however tightly he closed his eyes, the glare pierced through, blurring him into semiconsciousness.

‘We’ll leave the light on to keep you company – so you don’t get lonely.’ The thick accent made the sneer more biting, the mirthless laughter more sinister.

They had gone with a promise to ‘come and talk again’, the door banging shut, then firmly bolted.

The prisoner was enveloped by utter loneliness – and numbing fear.

Fear of being forced again to stand at an angle to the wall, his feet a metre from it, fingers resting against its whitewashed 2surface taking his bodyweight. Simple yet devastating. Any slump, and a strategic kick sent him back into position.

At first, he needed complete concentration just to stop screaming. Later, his senses were so deadened he could barely produce a grunt in answer to the endless questions – eventually sliding down the wall, collapsing on the concrete floor, too exhausted even to groan.

As their voices died away, he tried to get a grip. The room was bare, save for some old sacks in a corner. The bitter cold disorientated him. Surely this was supposed to be a warm country? Well, not this time of year. Not at night anyway. Not here in this remote building.

Painful memories returned. Feeling groggy on the car’s back seat; being lifted into a helicopter, half conscious, aware only of deafening noise.

Minutes later, bundled out again in the dusk and deliberately allowed to glimpse the total isolation: no chance of help.

Ever since his abduction he had implored them to explain. What did they want? Where were they going? Who werethey? But no answers. Instead, more questions, more accusations.

‘You’re making a terrible mistake. Don’t know what you are talking about. Don’t know anything. Anything …’

Even now, hours later, denials bounced round his aching head, seeming to echo away into the cold – only to be thrown back by the dazzle of light.

Then, through the silence, broken only by the unfamiliar screech of a hadeda, came a sudden, even more bewildering, thought.

They wouldn’t go to all this trouble for nothing.

Perhaps I am guilty after all?

If only they would tell me what on earth I’m supposed to have done.

1

Bound for the Great Wall, the minibus assigned to the so-called ‘Noted Persons Delegation’ pulled out of the hotel parking area and threaded through a swarm of bicycles into Beijing’s East Chang’an Avenue.

Professor Jim Evans, bookishly earnest, was fascinated by the cyclists’ dexterity: weaving, dodging, avoiding buses and cars, their bells ringing incessantly – the din intensified by continuous instructions to passengers from loudspeakers on trolleybuses.

Even louder were constant exhortations from speakers attached to patrolling vans. Political propaganda? No, Evans realised: traffic control.

The 50-kilometre journey northward to the tourist section of the Great Wall took longer than expected. Although cars were conspicuously absent, the roads were filled with packed buses, lorries, handcarts, even more cyclists and bullock carts – some piled high with produce or live chickens in bamboo baskets. Also, families on foot: some leading goats, or driving pigs and cows.

Vast fields stretched into the distance, framed by trees lining the roads. Despite the sense of great space, the countryside was too full of life to be desolate. There were clusters of commune 4buildings, and peasants in their production brigades tended fields of grain and vegetables.

‘What’s that?’ Jenny Stuart – charismatic, exuding warmth – pointed along the edge of the road where winnowed grain was spread thinly in bands several feet wide.

‘It’s laid out to dry,’ Evans explained, ‘the roadside’s the only free land available.’

He knew that just one-tenth of China’s land was cultivable. Other statistics almost defied comprehension – like the 35 million people employed simply to spread sewage on fields. For at least 4,000 years it had been the law that all excreta should be used as fertiliser, and collectors still called daily at every house with their barrows.

The driver revved his engine impatiently as they slowed behind a long queue of traffic in the foothills.

Wang Bi Nan, the interpreter assigned to them for the day, looked embarrassed. ‘Sorry for the delay. We have chosen to visit our Great Wall on a Chinese holiday.’

Wang, a thin balding man with horn-rimmed glasses, had joined the minibus just as it departed, unexpectedly replacing the official interpreter assigned to the delegation since their arrival.

The minibus wheezed up a steep hill alongside a sparkling stream, which disappeared between neatly cultivated terraces towards the fields below.

Excitedly, Evans caught his first sight of the Wall. Built of great stone slabs 2,000 years before, when China was divided into warring kingdoms, it stretched more than 4,000 kilometres from the eastern seaboard to the north-west. It was the only human-built landmark visible from space: perched high, straddling hill tops, winding its way through distant misty mountains.

Wang singled out Evans as the bus eased into the crowded parking area. ‘How about a photo? For your friends back home. 5You can tell them President Nixon stood on the same spot during his historic visit in 1972.’

‘Will your reputation survive that?’ muttered Jenny Stuart, sarcastically.

Wang took Evans by the arm and led him firmly up the wide steps onto the Wall itself. About ten metres wide and up to 40 metres high, the pedestrian section on top was paved and had parapet walls on either side where sightseers could lean.

Wang indicated key sights and trotted out historical facts and figures.

Then, pointing to the south-west, he said sharply: ‘There! That is where you were yesterday at the Atomic Energy Authority Institute. Did you enjoy the visit?’

He swung round suddenly. ‘I hear you were rude to one of our scientists.’ No longer smiling, his eyes were hard, watchful.

Evans was at a loss for words. What could the interpreter mean?

Sensing his uncertainty, Wang continued: ‘The scientist you sat next to at lunch was most insulted. Told us he had met many Western visitors, but none had ever questioned his professional integrity.’

‘What? I don’t know what you’re on about!’ Evans was bewildered.

Wang continued regardless. ‘As you know, he is one of our leading researchers in nuclear energy. That is why we agreed to your request to visit the Institute. But our scientists are dedicated to peace. They are most upset that you might think otherwise.’

‘But I don’tthink otherwise!’ Evans’ initial confusion turned to anger in response to Wang’s manner.

Collecting himself, he said stiffly: ‘There has obviously been a misunderstanding. Please apologise to my hosts on my behalf.’

Better to offer a straight apology. No point explaining his interest in the conversion from nuclear energy technology to weaponry.

‘Have you been photographed for posterity yet?’ Jenny called 6as the rest of the group joined them, clutching onto the handrail for the sharp climb.

‘Let me take one,’ she said as Evans nodded absently, his mind churning. He posed uncomfortably, hunching his tall frame, feeling embarrassed as the rest of the group watched.

‘Damn it! I’ll have to take another shot. Wang walked behind you that time and blocked the view. Smile please!’

They all took pictures of each other and when Wang firmly refused to pose with them, persuaded him to take snaps of the whole group using each of their cameras in turn. The light-hearted banter lifted Evans’ unease.

Wang struggled awkwardly with the different cameras. He was so different from their official interpreter, with her friendly proficiency. Again, Evans wondered why she had been replaced.

A group of Chinese teenagers passed by chattering excitedly. One, wearing a digital watch, posed by the side of the Wall as another took his photo. Then he passed the watch around so each of them could have their picture taken, sleeves ostentatiously rolled up to show it off.

Another sign of creeping consumerism, Evans thought. He recalled the car parked outside the main gate of the ancient Forbidden City which they had visited on their first day. The queue of Chinese waiting to be photographed by the car’s open door, their hands resting nonchalantly on the steering wheel, feigning ownership.

‘I’ll pass on your apologies.’ Wang had approached quietly, making Evans jump and jerk his gaze back from the sheer drop to the rocks below.

‘But if you want to meet other scientists during your stay you must avoid insults.’

With that, Wang nodded stiffly and strode back to the minibus, brooding in stony silence throughout the return journey.

Evans pulled out his notebook. At 33, he was one of the 7youngest professors in the field of nuclear radiation. He’d made copious notes the previous day while visiting the Institute.

The place had intrigued him.

Not just the old equipment left by the Russians when they suddenly withdrew their technicians in 1960 after the Sino-Soviet split. Not the appallingly rudimentary safety measures on the main reactor. Not even their hosts, who couldn’t have been more hospitable – the canteen at Aldermaston would never have turned out a twelve-course lunch of such delicacy.

No. It had been the scientist in green overalls who had spouted out facts in a machine-like monologue: an impressive feat, since his English was otherwise limited.

But some of the information didn’t add up, and Evans had put question marks in the margins of his notes. Now, he flicked idly through the pages – then suddenly stopped, shaken.

The relevant notes had been neatly removed.

Captain Mauritz Swanepoel was sweating profusely.

Despite the cold weather, the tension got to him every time he set the mechanism.

His colleagues said he sweated because he was unfit and pot-bellied; his wife said his diet was so bad his kidneys didn’t function properly.

He had a simpler explanation: fear. An odd emotion for a man whose trade was terror.

Earlier in his long career he’d been a member of the notorious Z-squad: part of BOSS, the South African Bureau for State Security. Named after the final letter in the alphabet, the squad specialised in ‘final solutions’ – the assassination of apartheid’s enemies.

Swanepoel had become expert in making and sending letter bombs. First victim: Eduardo Mondlane, leader of FRELIMO, the Mozambican liberation movement, killed in Tanzania. Next, exiled South African student leader Abraham Tiro, murdered in Botswana.

8Also, the device which killed writer and leading ANC activist Ruth First in Maputo – and the one which failed to detonate at the London family home of a British anti-apartheid leader.

When BOSS officially ceased to exist in August 1978, Swanepoel transferred to DONS: the Department of National Security. Then he joined the National Intelligence Service (NIS), where his expertise was much in demand. He dispatched letter bombs all over Africa, targeting organisers of the South African resistance movement: the African National Congress.

Currently he was an undercover agent in Harare, capital of Zimbabwe. He rented a house in Avondale, once a whites-only suburb but racially mixed since the early days of independence. Here, Swanepoel was inconspicuous, easily passing as a retired member of the old Rhodesian civil service.

Over 160,000 whites – about two-thirds of the white population – had emigrated to South Africa when Zimbabwe achieved majority rule in 1980. But some had returned, realising they could still enjoy a life of swimming pools and servants.

Swanepoel had stolen the identity of one such man: Paul Herson, a former civil servant who had actually died soon after moving to Johannesburg. Armed with Herson’s documents, Swanepoel was sent to Harare to coordinate covert activity against ANC leaders based in the city.

Now, he crouched under a spotlight making final adjustments to the device clamped to his bench. Consisting of metal cylinders and wires protruding from a balsa wood base, it was slim enough to slip into an A4 jiffy bag, and could pass as a large book.

The trickiest bit was setting the gap between the contacts. The device exploded when pulled out by the unsuspecting recipient, leaving behind a small plastic disc attached to the inside of the envelope and positioned between the contacts. If they were set too close, the disc could not be inserted. If they were set too far apart, it didn’t go off.

9This one was destined for Robert Temba, the Harare-based ANC commander. South African intelligence believed he was training black resistance fighters in sabotage techniques and infiltrating them into the country. They also suspected he was behind recent bombings of South African defence installations.

Swanepoel gingerly fitted the disc between the contacts, tested it to his satisfaction and ran a final check on the letter bomb. Then he carefully inserted the device into a large envelope he had acquired from Harare’s Grassroots bookshop. Its label would not invite suspicion.

Exhausted and stressed, he reached for a new bottle of his favourite South African brandy, KWV. Tomorrow he would drop off his package at a post office in the city centre amidst the lunchtime crowds.

Two days later it should reach its destination.

It was three years since the first limpet mine had exploded in the harbour.

Dick Sewell was thrown half-asleep from his bunk bed in the stern of the eco-activism ship. He hardly heard the shouts and screams of the eleven other members of the crew. The shock of the explosion battered his eardrums almost senseless.

Sewell dragged himself off the floor and made for the deck, hardly conscious of an ugly gash on his left leg, or his bruised back. Seconds later the converted 40-metre fishing vessel, belonging to the international environmentalist organisation Green Planet, started to list.

Numb and disorientated, he caught a glimpse of the Green Planet flag fluttering in the harbour breeze. Then a second limpet mine exploded through the hull and the boat began sinking.

Quick, get into the dinghy!

Move!

Where are the others? Yes – some already climbing in, some 10jumping into the water. Shouts. Let’s check – is everyone alright?

Wait … where’s Maria?

Sewell struggled back down to the bows where the young medic had been sleeping. Water was pouring in, the darkness was menacing. He thrust his way forward, desperately calling. Maria must be there!

Come on, come on, where are you? The mess was terrible: documents, bedding, food, personal possessions everywhere – and a smell of oil.

Through the gloom he spotted the medic’s bunk. Or what was left of it. Maria’s body, torn by the explosion, was sinking in the rising water.

Sewell shook her frantically, uselessly. Christ, no!

A shout from the deck: ‘Dick, what the hell are you doing? Get out! It’s going under!’

Sewell woke up with a start. His heart still pounded, and his mind raced as he lived it all again. His own horrific, recurring nightmare. He took a few deep breaths. Tried to compose himself.

Now he was on another anti-nuclear mission in a very different part of the world. He stretched out, arms behind his head. It was only 3 a.m. but he knew he wouldn’t get back to sleep.

Muscular and fit, Dick Sewell was still haunted and hardened by the might of the explosion. Soon afterwards, he gave up his job as a PE teacher to work fulltime for Green Planet. He’d never regretted the decision. He felt privileged to have found his life’s mission.

But his personal relationships suffered. He moved out of the small flat he had bought with his girlfriend in a working-class area of East London, rapidly being gentrified. She was fed up with him. He was increasingly obsessed with his political activism, and never around. Married to Green Planet – not to her, as she’d once hoped.

11Sewell moved into a bedsit. He joined Green Planet’s non-violent, direct-action group. He protested against the hunting of seals in Canada, and the dumping at sea of nuclear waste. He volunteered for an expedition to disrupt the annual massacre of thousands of pilot whales in the Faroe Islands. Such carnage. The hunters claimed they were killing for food, but it was really just for sport.

Was he a driven man? Boringly, exclusively, dedicated to his mission? Sure, he wasn’t like other blokes. He didn’t have time for women or drinking, but that didn’t make him better or worse – just different. He could be content with that. Though sometimes he felt wistful for what he might be missing.

He was jolted back to the present by the snores and grunts of other passengers on the train. Soon it would be dawn. Out there was another country to add to his list: a new challenge in a strange place. He felt the usual excitement and fear.

But this might be his most dangerous assignment yet …

Normally, Green Planet operated openly, but this time his instructions were to contact an underground group in China: a nation known for its intolerance towards dissidents. He’d need cover, of course. That’s why he’d been told to join an official tour group so he could blend in.

Stomach tightening, he wondered about his task in Beijing, still hours away, on this long train journey from Shanghai.

Chung Kuo: the Chinese name for their country. Literal translation, ‘Middle Kingdom’: the centre of world civilisation, containing one-sixth of the human race.

Jenny Stuart remembered this as the minibus drove through the gates of the English Language Institute, not far from their hotel. She’d been asked to give a current affairs lecture to the students, and was feeling rather nervous.

‘I’ve no idea how much English they’ll understand,’ she had confided to Evans. ‘It’s difficult to know how to pitch it.’

12‘I’ll join you. Should be worth it – an English socialist lecturing the Chinese on socialism!’ he’d teased.

They were accompanied by their official interpreter, Shu Li Ping. She was delighted to return to the Institute where she had learned English. Unusually, she had also studied in Britain for two years. She wore Western style skirts and blouses and quizzed Jenny keenly on the latest London fashions and pop groups.

But she was evasive when Evans asked about her absence earlier in the day. ‘I was needed for other duties,’ she replied, quickly changing the subject.

The chatter in the packed lecture hall hushed as they entered. Evans took a seat at the back while Jenny walked to the platform, watched curiously by 200 mostly male students. He could imagine how she was feeling: those nagging nerves whenever one was about to address an unknown audience.

‘I don’t like it when people speak in a self-indulgent way,’ she had told him on the way to the Institute. ‘It’s important to make the effort to relate. You won’t communicate anything of value unless you do. That’s something we emphasise in the women’s movement.’

As Jenny took her place at the podium, her tension seemed to vanish. She began by greeting the students. Then, with an air of authority, she quipped: ‘I know I have blonde hair, but I am not Margaret Thatcher!’

The students burst out laughing as Jenny had hoped. She’d heard of the impact made by the British Prime Minister on a visit to China. She relaxed – and so did Evans, realising how anxious he had been on her behalf. He found himself studying her closely.

Aged 25, she was a South London social worker. She’d become active in student politics while studying history at Sussex University. Her tutor had been on the committee of the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding, and had put forward her name for the delegation.

Jenny had an enthusiastic manner and was good 13company – though her penchant for straight talking sometimes caused offence.

Now she was forcefully defending her membership of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She questioned China’s possession of nuclear weapons, and asked why it was reluctant to criticise America’s escalation of the arms race when it condemned Russia’s. She also challenged China’s foreign policy: particularly its indirect support for extreme right-wing movements, and regimes like the Chilean junta.

‘It is wrong to adopt a certain stance simply because it is the opposite of Russian policy towards a particular country. In the case of South Africa, how can China possibly justify its refusal to back Nelson Mandela’s ANC, just because it received Soviet aid? Apartheid is an evil. Our two nations, China and Britain, should adopt a principled foreign policy not aligned to either of the Cold War superpowers.’

Jenny Stuart was a charismatic speaker: a quality Evans found intriguing in people who were not pushy or egotistical. He observed how her swirling white skirt and close-fitting jumper accentuated her provocative figure, in contrast to her usual jeans and shirt. But then he felt guilty. Was he objectifying her by indulging in such thoughts?

Jenny sat down to an enthusiastic ovation. He wasn’t surprised. It was always a sign of success when the audience laughed naturally at jokes. Though sometimes, exactly the same jokes went down like a lead balloon.

Nevertheless, Evans was struck by how well the students responded to Jenny’s ironic humour. And they had obviously followed her arguments closely because they were now vying with each other to fire questions: mostly about foreign policy and disarmament.

‘Don’t you understand,’ one addressed her earnestly, ‘the Soviets have been aggressors throughout our history. They even failed to support us against the fascists at a critical time in the 141930s. Now their missiles are pointing at us all along our border. Remember Czechoslovakia. Remember Afghanistan. Never mind Gorbachev – the Soviets are expansionary imperialists!’

Jenny responded to each point carefully and patiently, impressing Evans with her calmness and the way she treated every questioner with respect. The students were lively and articulate, making their points openly, often disagreeing amongst themselves.

There was none of the rigidity or uniformity Evans had anticipated. Nor were there any taboos. They applauded again at the end, and a small group gathered round Jenny, chatting excitedly, asking more questions.

She beckoned him over. ‘Some of them want to talk to us back at their hostel. We can’t meet them tonight because of the banquet. What about tomorrow?’

Evans was surprised, but nodded in agreement. He’d heard that Chinese people were wary of foreigners and didn’t tolerate open discussion. Yet these arrangements were being made easily and spontaneously.

‘You will be coming too?’ A bespectacled youth with an intense expression addressed him anxiously. ‘She told us you are an expert in nuclear technology. Please give her this.’ He pressed a piece of paper furtively into Evans’ hand and slipped away.

‘A lively bunch.’ The familiar voice of Harold Williams – another member of the delegation – startled him.

‘They certainly are,’ said Evans, instinctively pushing the paper into his pocket. ‘I didn’t realise you were here. Are the rest of the delegation with you?’

Williams shook his head. ‘I was a little late. Thought I’d come and listen to Jenny. Polished performer, isn’t she?’

With his heavy jowls, Williams had the slightly pompous air of a government official, which was what he had been. Something in the Foreign Office before his retirement the previous year? Evans couldn’t recall exactly what he had said.

The interpreter Shu shepherded them outside to a blue-grey 15Shanghai sedan, based on a 1950s Mercedes design. The most common kind of official transport.

Cars of different sizes and colours were allocated strictly according to rank: blue-grey for the lower orders, large, shiny black ones for senior Party cadres. As with all official cars, the rear window was curtained off – for reasons of privacy, Shu said.

‘So ordinary people can’t see who’s being chauffeured about!’ Jenny whispered sceptically to Evans.

Their driver banged his horn incessantly, hooting to announce presence, not to give a warning.

Back at the hotel, Evans drew Jenny aside as they walked with Harold Williams to the lift. ‘Could you come to my room? Got something to show you.’

She looked at him warily, wondering if he was making a pass at her. But, intrigued, she nodded.

Inside his room, he showed her the scruffy bit of paper.

‘Thought I should wait until we were alone. One of the students asked me to give this to you,’ he explained, sheepishly.

She stared at it, perplexed: CHINA FOREIGN POLICY SINCE 1978. DISCUSS IN DETAIL.

‘What is that supposed to mean?’

‘No idea – looks rather like an essay title. We’ll have to ask him tomorrow when we meet again at the hostel.’

As she closed the door, he looked again at the paper.

Another strange incident.

Should he tell her about the notebook, and the weird exchange with Wang?

Or was it simply too trivial?

The newsflash interrupted a music programme on Swanepoel’s car radio.

‘There was an explosion an hour ago at the Harare home of African National Congress organiser Robert Temba. Several people are feared dead, but no further details are available.’

16Swanepoel let out a whoop of delight and speeded back to his house to contact his ‘handler’. Almost immediately he began to think about the next stage of their plan: codename NOSLEN – the first name of the imprisoned ANC leader Nelson Mandela, in reverse.

His letter bomb had been delivered as scheduled. Scrutinised and scanned by the team who guarded Robert Temba’s home 24 hours a day, it was passed to his twelve-year-old daughter, Nomsa.

‘Can I open it, Dad? It’s a package from Grassroots. Looks exciting!’

Temba had a lot on his mind that morning. He was in a ‘Dad’s daze’, as his three children fondly called it: registering family life going on around him, but not engaging properly with it. Most of the time, he could only really focus on the challenges of coordinating ANC resistance activities.

The pressure had been intensifying relentlessly. Following Mozambique’s non-aggression pact with Pretoria, most Frontline States no longer allowed ANC bases to operate from their territory. So, the ANC devised a new strategy: to ferment military action at home, in South Africa’s black townships. Temba played a key role in this task.

Now, he glanced at the package, vaguely registering the bookshop label, and nodded to his daughter. Then he took the rest of the mail to his study, at the rear of the bungalow.

There was a deafening roar.

Temba instantly grasped the enormity of his error. In desperation, he tried to run towards his daughter – only to be knocked over by falling masonry and buried under rubble.

There was nothing left to identify Nomsa. No corpse. Her small body was torn apart: lumps of flesh and bone fragments, scattered through the pile of bricks and wood which had once been the family living room.

Some patches of dust were darker and damper than others. 17Redder, too. A foot, torn from the child’s leg, stuck incongruously out of a still-shiny shoe.

The ANC security guard was trapped under a collapsed door arch. He peered half-conscious at the gaping hole in his stomach and closed his eyes in horror. They never would reopen.

A grim silence descended, broken only by water gushing from broken pipes.

The Shanghai express pulled slowly into Beijing station as Dick Sewell leaned out of the window for his first view of the city.

Swarms of people filled the station concourse.

The overnight journey had been comfortable enough. As arranged with his Green Planet colleagues he was travelling incognito, with a regular tour party of holiday makers. They travelled ‘soft class’: in compartments with four berths, the thick mattresses and lace curtains signifying foreigners, senior officials, or army officers.

Locals travelled ‘hard class’, jammed together in wooden triple-decker bunk beds with no mattresses, exposed to the smoke-filled corridors.

Led out by a guide from the station towards a coach, Sewell was weary after the long trip, hours of sleep lost after his nightmare.

It was early evening, and he was looking forward to a shower. Then maybe a cold beer and a walk to suss out the bar where he was due to collect a package from an unknown contact the following evening.

Despite the city’s humidity he shivered with apprehension.

The buzzer sounded at 9.16 a.m. in Major Keith Makuyana’s office in security headquarters.

He picked up the phone immediately, listening intently, writing down details, asking questions, thanking the caller for his trouble: an old friend on duty at Harare police headquarters.

18The two had been active in ZANLA, military wing of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), whose successful liberation struggle had propelled it to power in1980. Now, they had an understanding: Makuyana would be tipped off about any politically sensitive incident. This would enable him to troubleshoot potential rivalry and jealousy between the police and his own intelligence organisation.

Makuyana’s brief was to maintain links with the South African resistance – also to monitor the apartheid government’s attempts to disrupt such resistance, or to interfere in Zimbabwean politics.

A tall, lean man, he always wore dark prescription glasses. This gave him an air of menace, though his staff worshipped him for his loyalty and kindness. Now he was on the phone to them, issuing precise, clipped instructions.

Exactly two minutes later, an unmarked Nissan estate car was waiting in the underground car park. He strode out of the lift and climbed in, with two of his officers.

Immediately behind was a grey Volkswagen Transporter, also unmarked. It looked rather dilapidated. Nobody would have guessed it was armour plated and contained a folding bed, medical equipment, a range of arms and sophisticated electronic gadgetry.

Makuyana reached his destination just ten minutes after his buzzer had sounded. Police and soldiers were milling about, cordoning off the bystanders, who had gathered in shock outside what had been Robert Temba’s house.

The VW van had pulled up 100 metres away, parking discreetly as Makuyana’s car arrived.

He quickly took control, flashing his ID with a word of explanation.

The house had been sealed off and was being searched. Makuyana restrained himself from a feverish urge to tear into the rubble in case there was still some life. He was close to the 19Temba family and had enjoyed many hours of hospitality in the now unrecognisable bungalow.

Makuyana forced himself to search methodically. Obviously, the explosion had occurred near the entrance, where the corpse of the security guard now lay. No chance anyone else would have survived in that part of the house. He moved to the rear.

A shout from his sergeant: two bodies, then another. Two children and their mother, all dead, crushed under the building, covered in dust. The younger girl still clutched her doll – its severed head was lying beside her.

He turned, his dark glasses hiding his pain. Where was Robert? Had his old friend been out of the house? He felt a glimmer of hope – then he stumbled over another body.

The ANC organiser was lying flat on the floor, holding some brown envelopes, his head in a pool of blood. Makuyana stooped to turn the body over, preparing himself for the inevitable.

But then … something unexpected. Years of experience had taught him that dead bodies felt different. He reached for Temba’s pulse. Yes! A few flickering signs of life.

God, let it be so, he willed desperately.

Keith Makuyana had a reputation for being cool and professional under pressure – and for making decisions quickly. Sometimes that got him into trouble: especially when navigating internal office politics. But he didn’t care. He was not a desk man. He came into his own in the field.

Now – as he considered the options – he fought to overcome the emotions of a close friendship lost. The ambulance would be here soon. So would the other emergency services and police reinforcements. He called his officers over.

‘Cover this man up. I don’t want anything showing. But treat him very gently. He may still be alive. Then get the other bodies and lay them out in the front garden. Leave a mark where you found them.’

Grabbing a radio handset, he spoke urgently to colleagues in 20the grey VW van. It was 9.36 a.m. – barely ten minutes after he had arrived on the scene.

Apparently, a fire had broken out at the National Sports Stadium over the hill along the Bulawayo Road, and there was still no ambulance. It gave him the opening he wanted, and he went over to the police guarding the crowd.

‘Six dead, the whole family and one security guard: no survivors. Get those bodies on the lawn covered. I want them out quickly. There’s going to be one hell of a political row, and we don’t want anyone getting in the way while we investigate.

‘One body is in a really bad state. My men have covered it up. We can’t wait for an ambulance, so they will take it now. Then the forensic boys can come in and get a clear look at the house. They must leave no stone unturned. I want a full report. We must get to the bottom of this – and quickly!’

As he was talking, the grey VW van slipped down the drive, its sliding side door opening out of sight of the spectators. Temba’s battered body was lifted gingerly onto the mattress inside the vehicle.

Makuyana climbed in the front and the driver radioed ahead. Not to the main hospital, but to special premises whose existence was known only by a chosen few.

On the way the VW passed an ambulance tearing towards the scene, siren blaring. Meanwhile Makuyana’s remaining officers performed a rapid, systematic search, gathering up any legible documents. They had almost finished when the local police superintendent arrived to take charge.

Beijing was pitch dark when Evans and Jenny were dropped outside the imposing gates of the student hostel, where eight young men waited expectantly.

They looked like any group of students thought Evans, except for their shiny dark hair in neat crewcuts, open-necked shirts and cotton trousers – so different from the jeans and sweatshirts of their British counterparts.

21‘We were not sure you would come,’ said a lanky youth, as he courteously led the way towards one of several drab concrete buildings.

No lift, so they climbed to the fifth floor. The meeting was in a room about 10 metres square – typical, they were told. Bunk beds on either side, desk at the end: lodgings for six students.

The students crowded into the small room, some sitting on the floor, others on the bunk beds and even the desk, their visitors given the only two available chairs.

As they were about to begin there was a late arrival – Hu Shao Ping, the student who had secretly passed Jim the note yesterday.

Short and slightly built, Hu looked older than the others. His eyes anxiously peered from behind round thin-rimmed spectacles, and he seemed to carry a heavy burden on his slim shoulders. Apologising for his lateness, he said he had been delayed at home: unlike the others he lived with his parents.

Soon a lively discussion developed about China’s foreign policy, as tea was handed round in an ill-matched assortment of mugs.

The students argued, cracked jokes and told stories. Each was openly cynical about the ruling Communist Party, blaming it for betraying the revolution’s ideals.

‘Is anyone a member of the Party?’ Jenny asked, surprised at their candid opinions.

Only one youth embarrassedly raised his hand, and was ribbed by his friends. Several volunteered that they had demonstrated against Party authoritarianism and the lack of democracy.

Others explained that, although the Party was all-powerful and seemed huge with its 42 million members, this figure was actually less than 4 per cent of the population.

‘What do you remember of the Cultural Revolution?’ asked Jenny.

She’d read of the tumultuous years after 1966 when Chairman Mao’s young Red Guards had acted as vanguards of revolutionary purity, fighting for political and social renewal.

22‘You would have been small children then. Could we have had this sort of meeting?’

‘Never! We would have denounced you as foreign imperialists and chanted at you with our little red books!’ They all burst out laughing: thrusting up their hands, clutching imaginary booklets, punching the air in imitation of the Red Guards.

All, that is, except Hu Shao Ping, who had barely participated. He merely listened studiously, studying the two foreigners.

Evans, remembering Hu’s request the day before, tried to draw him in.

‘What do you think? Are they correct?’

‘My father was very badly treated then,’ he answered carefully.

A silence descended on the room as the laughter ceased and the others turned to him respectfully.

Evans sensed his diffidence: ‘What happened?’

Hu slowly told his story in the clear, clipped English they had all mastered, encouraged by his friends whenever he faltered.

‘My father is a scientist – a nuclear physicist,’ he bowed to Evans.

‘He studied first in America, but after Liberation in 1949 he came back to help build a new China. When Mao launched his cultural revolution with his famous swim in the Yellow River in 1966, my father was a respected member of his profession.

‘Then some local Red Guards found out he had been a student in the USA, and denounced him as a “rightist” and an “imperialist”, even though he had always been a communist.

‘He was taken away one night by a mob and beaten. They imprisoned him in a basement room at his work for several months before he was dispatched to a remote village in the mountains.’

Tears welled up and were impatiently blinked away. ‘My father had so much knowledge. But they made him work all 23day with a pickaxe in a quarry. Our family were all denounced as “rightists”.

‘My mother is a nurse – she was forced to clean floors and toilets of the hospital ward where she had once been supervisor. My older brother and sister were both expelled from their junior high school and assigned to street cleaning. I was still an infant, but we all suffered by being children of a “reactionary”. They destroyed our family.’

‘What a terrible waste,’ Jenny murmured.

Hu sighed, nodding. ‘The Cultural Revolution wasa waste. A disaster. Over a hundred million people were persecuted. The tragedy is that Mao started the Cultural Revolution to rid the country of complacency, corruption and bureaucracy. He wanted to recreate the socialist momentum which followed Liberation. But it became a nightmare.

‘Only after Mao’s death and the overthrow of the Gang of Four – which had been running the country in his name – did things begin to improve.

‘My father was brought back to work again as a scientist, though at a lower grade. My mother also got her nursing job back, and we children tried to make up for lost years. But my father never fully recovered his health. He is now retired.’

Hu paused, looking intently at Jenny: ‘I told my father about your lecture. He wants to meet you both. Can you come to my home?’

As Jenny and Evans looked doubtfully at each other, he added quickly: ‘Please do not refuse. I will accompany you on the bus later, and we can talk more.’

The discussion continued for a while longer, and then the students escorted their guests to the hostel gates.

‘I’ve learned more tonight than from all the delegation briefings,’ Evans remarked, shaking hands with each of them.

As they walked with Hu to the bus stop on the main road, Evans noticed how badly lit the streets were. Yet he felt 24safe – quite different from London, where he felt increasingly insecure out at night.

‘By the way,’ he remembered to ask as they reached the bus stop, ‘What did that message mean: on the paper you gave me?’

‘My father will explain. It is something important that he found when he worked at the Atomic Energy Institute. As I said, he retired only two months ago.’

‘You mean the Institute at Nankow?’

‘Yes.’

‘I visited it earlier this week.’

‘You did? Even better,’ Hu smiled – for the first time that evening. ‘When I told him of Miss Stuart’s lecture and of her criticisms of China’s foreign policy, and that you are a nuclear physicist, he immediately wanted to see you. You willcome, won’t you?’

The trolleybus arrived and they all climbed aboard. ‘Can’t you tell us more?’ Jenny asked.

The bus pulled away, its doors swishing closed, and then stopped almost immediately to let on a tardy passenger. Panting, the man brushed past, taking a seat at the back as the bus jerked off again.

‘I am sorry, I do not know all the details. My father was insistent on talking to you personally. He is worried about China’s nuclear programme and its foreign policy. He also supports your strong opposition to the apartheid regime.’

‘South Africa! What’s that got to do with it?’ Jenny asked.

Hu shrugged; he didn’t know.

‘I suppose we could squeeze in a visit tomorrow afternoon,’ she said, and Evans nodded. The mention of the Institute had reminded him of the missing page in his notebook.

Hu smiled again. ‘I will come myself to collect you. Your hotel is not very far away. And we can easily take a bus to the place where I live.’

25‘What is your home like?’ Jenny asked.

‘It is in a hutong–a traditional alley in the old part of the city. It’s a small house with four rooms built around a courtyard compound. We share our toilet and kitchen with neighbours. It used to belong to my grandparents.’

He glanced out of the window. ‘Look down the next street. If it is light enough, you will see our house sticking out from the first hutong on the left. I will meet you tomorrow at 5 p.m. on the pavement outside your hotel gates.’

‘Why not wait in reception, in case we’re late?’

Hu laughed, shaking his head. ‘As an ordinary Chinese, I may not enter the hotel without special permission.’

Then he pointed: ‘Look! There is my home. The one with the chimney sticking out above the street wall.’

The bus stopped and Hu got out, waiting formally by the kerbside until the doors closed and it moved off.

As his slight figure faded into the darkness, there was a shout from the rear of the bus. The driver answered, obviously angry. The passenger shouted back, and the bus screeched to a halt.

The back doors opened and a man climbed out. The same man who had boarded at the last minute, outside the hostel.

The lead story on Voice of Zimbabwe’s news programme was brutally direct: ANC official Robert Temba and his entire family were dead after an explosion at his house.

There was a brief obituary praising Temba’s commitment to the ‘heroic struggle for liberation’, and a statement from an ANC spokesman, angrily denouncing ‘South African terrorism’.

In the safe house near the city centre, Keith Makuyana switched off the radio. So far so good.

But his immediate anxiety was whether Temba would pull through: he was still unconscious. They had taken him to a purpose-built medical centre at the back of the building, acquired several years before under a Presidential directive.

26Very few knew of its existence. Not even the President’s coterie of security and military advisers, who were rapidly becoming a ruling junta as the values of the freedom struggle faded fast.

Makuyana felt increasingly estranged from the corruption and authoritarianism spreading throughout the system. He was also unhappy about the fusion of the state and ruling party. The intelligence service would soon be a tool of Presidential fiefdom, instead of the guardian of national security.

But this was not the time to worry about the future. He had work to do.

The safe house resembled an old-style Rhodesian family home, now sandwiched between rows of office blocks: a relic of a colonial age in an area which had been extensively redeveloped. The spacious back garden was long gone – replaced by another set of buildings which could not be seen from the road.

The grey VW van was parked in a covered garage, next to several other vehicles. Beyond, was a central corridor with rooms on either side.

Down a flight of stairs, through a security door, was a central control room. It boasted a sophisticated communication system, which linked to the medical centre – and every part of the country.

A skeleton staff maintained its facilities all year round and monitored events 24/7. Now they were joined by others, who brought a sense of urgency to the usual calmness.

‘Still no leads?’ Makuyana was getting impatient. His officers recognised the mood only too well. They exchanged glances, as he paced round the bank of monitors, telephones and printers.

Despite a thorough search of Temba’s ruined house, they had uncovered no evidence to trace the source of the bomb. All they knew was that the time of the explosion coincided with the mail delivery. The postman remembered an A4-sized package addressed to the ‘special’ Temba household, but it wasn’t large enough to arouse suspicion.

27Makuyana’s team had interviewed staff at the mail sorting office, where the atmosphere was tense. They always took great care when handling bulky packages addressed to ‘special’ households. Letter bombs were a real nightmare: any rough handling or a small fault, and they could explode at any stage of their passage through the postal network.

But somehow, the Grassroots envelope had passed through the system, undetected.

‘Run another check on suspected South African agents in the country,’ Makuyana instructed. ‘And ask for a priority monitor on any irregular communications to South Africa since this morning: phone calls, radio signals, the lot. Whoever was responsible must have reported back.’

A very long shot: his staff could spend hours fruitlessly combing surveillance records and double-checking intelligence reports – but there was little else to go on.

Makuyana strode through to the medical unit. He peered anxiously at the screen displaying Temba’s erratic heartbeat, and listened to his comrade’s fitful breathing.

‘Will he pull through?’ It was mid-afternoon and he needed to know. Perhaps the ANC man could remember something important.

‘An outside chance,’ the young doctor replied. She looked at Makuyana, sensing his anxiety. ‘He’s important – yes?’

‘Very.’

She knew, and sympathised. ‘I may be able to bring him round so you can have a few words. But the trauma could finish him off. He shouldn’t really be forced prematurely into consciousness. My professional advice is to let him rest. But …?’ She held his gaze: questioning, not judging.

Makuyana looked away. ‘Bring him round as soon as you can.’

His words ricocheted harshly off the stone floor, as he abruptly left the room.

2

Evans spent the day meeting more scientists, and being briefed by officials from the Chinese energy ministry. He also had time to think and update his notes.

He had slept badly. His mind kept racing all night: the confusion over the notebook, Wang’s menace – the coming visit to meet Hu’s father.

Now, with a free half hour, he forced himself to relax. He sat down on the steps of the Great Hall of the People, a short walk from his hotel, trying to imagine what it must have felt like to witness one of Mao’s famous addresses to the cheering masses assembled below.

Tiananmen Square stretched out before him, the towering Martyrs Memorial honouring revolutionary heroes on one side, a vast area which had held over a million people in its time.

Now it was calm in the afternoon sun, as people went about their business, some pausing to stare at him. As a white foreigner, he was an object of curiosity, but their stares were respectful, not intrusive.

Evans found this place deeply compelling – even though he was wary of behaving like latter-day colonialists who patronisingly ‘fell in love’ with developing countries.

29But he couldn’t help being captivated by the straightforward dignity of the Chinese people, and the way their courtesy and old-fashioned formality contrasted with the informality of their attire. Even on official visits, open necked shirts and slacks were the norm, and he had been happy to jettison his own tie and suit for more casual attire.

Paradoxically, the more he discovered, the more questions he had: especially about the use of power, and how ordinary people lived and thought.