Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Bradecote & Catchpoll

- Sprache: Englisch

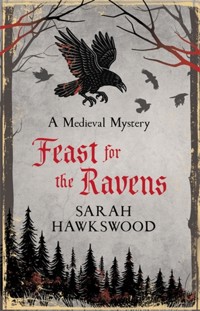

'Chilling and riveting. This immersive, evocative book will grip you from first page to last' S.D. Sykes Worcestershire, September 1145. A Templar knight is found dead in the Forest of Wyre, clutching a bloodstained document naming a traitor. Undersheriff Hugh Bradecote, Serjeant Catchpoll, and Underserjeant Walkelin must uncover whether the killing was personal, political, or the work of outlaws. They are surprised to find that the locals believe the killer to be the Raven Woman, a mythical shape-shifter said to haunt the woods. Then the knight is identified as Ivo de Mitton, who fled the shire many years ago, presumed guilty of the foul murder of his kin. As the trio dig through legend and lies, they must determine the truth and bring a cunning killer to justice. 'The series sets the yardstick by which all historical CriFi should be judged' Fully Booked

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

Feast for the Ravens

A Bradecote and Catchpoll Mystery

SARAH HAWKSWOOD2

3

For H. J. B.

4

5

6

7

Letan him behindan hræw bryttian

saluwigpadan, þone sweartan hræfn,

hyrnednebban, and þane hasewanpadan,

earn æftan hwit, æses brucan,

They left behind them, to enjoy the corpses,

The dark-plumaged, swarthy raven,

Horny beaked, and the ash-plumaged

Eagle, white behind, to partake of the carrion

From ‘The Battle of Brunanburh’, Old English poem8

Contents

Chapter One

Two days after the feast of St Gregory the Great, September 1145

The knight rode slowly, on a loose rein and clearly lost in his own thoughts. A frown drew his brows together as though they might whisper secretively of what was going on in his mind, but he looked otherwise impassive. He was trying to remember topography from his youth, though in doing so he was assailed by other memories, mostly of the man who had journeyed with him for over two decades, and was now growing cold and stiff in the clearing where he had left him. He apostrophised himself out loud, and his horse’s ears flicked back and forth, perhaps expecting an admonishing pull at the bit. It was foolishness, he told himself, to think of the past, for it was gone and irrelevant. What lay ahead was the future, and one that had more purpose than any in the years of exile. To achieve that he must follow his plan in every detail, but one doubt remained. Did the brook, whose name at present still eluded him, truly mark the shire boundary, and was it recognised by those who lived on either side? Either way, it would be best not to go far, not yet. There was no need for haste, for the body would surely not be discovered for several days at least, since it lay out of sight off 10the trackway, and any hue and cry would be half-hearted. By the time any report of it reached Worcester the trail would be colder than the corpse.

The track was descending now, and glimpses of the Severn to the right-hand side were spasmodic in the fast-fading daylight. The undergrowth beneath the trees was a little thicker on the left side, and a stunted holly, kept bushy by the overarching branches of oak and beech shading it from the light, would be good cover. He brought his mount to a halt and dismounted, leading it and the spare horse off the trackway and behind the screen of prickly leaves, where he hobbled them. Then he took a roll from behind his saddle, removed both surcoat and, with some grunting, the encumbering mailshirt, and transformed from Templar into anonymous rider. It was a perfectly good place to make camp for the night, so he scuffed an area bare with his boot, and gathered bark and twigs for a small fire. The autumnal display of nuts and berries would supplement the bread and smoked fish he had in his pack, and of course that was now feeding not two but only one. When later he slept, his dreams would not be haunted by ghosts of his own making.

It had been a good summer, with ample sunshine to warm the red earth and ripen the wheat, and sufficient rain to swell the grain. When Herluin the Steward had rubbed the kernels from a golden head of wheat in his weathered palm, he had smiled as he declared the crop ready to harvest, and in the frantic days that followed, the weather had held. Now the last stooks in the great field had been piled onto the ox wagon, the expanse of stubble was silent and empty, and the threshing barn was busy. A huge 11sense of relief pervaded the manor of Ribbesford, for the granary would be full and the spectre of hunger was banished from the following summer. It was not a large manor, being limited to the east by the flow of the Severn, which flooded its fields in wet winters but made them fertile, and the rising high ground of the Forest of Wyre curling about it, almost protectively, on all other sides. Had it not been for the ford, and the track from it that passed by church, hall and the cluster of lesser dwellings and barns, it would have been a hidden and secret place.

The children, who had toiled from dawn to dusk alongside their mothers during the harvest, gathering the sheaves, had now been released from their labours and given freedom for a couple of days. There were blackberries bejewelling the hedgerows about the harvest-shorn fields, and in the woods the first cobnuts were beginning to fall as the leaves lost their lustre, pattering softly upon the woodland floor. It was a fine late summer morn, warm from the first, for the autumnal chill and change to the scent in the air was still perhaps a week or two away. Edric and Agar’s mother had given them each a willow basket and sent them off early, telling them that they should make themselves useful and forage for some of the seasonal bounty when they had finished wasting their time trying to catch fish in their hands in the still summer-shallow water of the ford. The lord of Ribbesford was a fair man, and the depredations of two small boys upon bushes and boughs that were ‘his’ would not attract his wrath, especially in the aftermath of a successful harvest.

The ford, which would be viable until the late autumn rains in Wales raised the Severn, was a favoured summer haunt for 12the boys, but almost as soon as they had begun paddling their older cousin, Wulfric, arrived, and began skimming stones aggressively across the water, his dark brows drawn in a scowl that boded ill to anyone who got in his way, especially if they were smaller. Edric and Agar looked at each other and sighed, since even the most sluggish fish would be disturbed, and there was no guarantee that their cousin, in such a mood, might not throw stones at them. After a murmured conversation, the brothers agreed to look in the woods for cobnuts first, so that they could have a competition to see who could collect most nuts and any berries they picked afterwards would not get squashed. They returned up the track, skirting about the barn in case a grown-up came out and decided there was a task for them after all, and past the church, set where the ground began to rise and above any possible flooding. The woods rose more steeply to their left, and were dominated by the ‘big trees’, sessile oak, ash, yew and beech, with hazel and elderberry scattered thinly. To their right, the high ground descended gradually as it approached the willow-and-alder-edged river, but then veered sharply northward as if shy of the water and the red sandstone crag that faced them from the eastern bank. There were plenty of hazels here, but none had been touched by the manor children for fear of the Hrafn Wif, the Raven Woman, a figure perceived more as some evil combination of witch and ghost than a creature of flesh and blood. She had become a fireside tale, and grown more frightening in the telling, and those adults who did not quite believe it were content to use her as a way to deter their children from playing by the river’s turn, where the current ran stronger and they 13would be beyond earshot if they called for aid in difficulties.

‘Shall we go that way?’ Edric whispered, as if the Raven Woman would hear them.

‘I dares not.’ Agar was the younger by a year and a half.

‘But we need not go too far, and look at that tree just over there. There be big nuts on it. And think – Wulfric will look small when we ’as been brave and done somethin’ even ’e dare not.’ Edric was trying to boost his own courage as much as that of his sibling.

Agar dithered. ‘If we just goes a little way, then mayhap she will not find us?’

‘Surely she will not. Come on.’ Edric took his little brother’s hand, and they stepped aside from the track into the woods. A squirrel, agitated by their arrival, disappeared in a flash of russet accompanied by alarmed churring and quivering twigs, which sent their hearts beating faster, and Agar gripped Edric’s hand even more tightly. Edric tried to laugh it off and pretend that he had not been scared at all. The first tree they plundered for fallen bounty and those nuts that they could shake down with sticks provided cobnuts of great size, but too few were quite ripe enough to come loose. Pleased with their initial success, and arguing mildly over who had the most, the boys relaxed, and moved a little lower down the slope and more towards the river, beyond the sight of the track. An even better tree tempted them across a small, sunlit glade, where the gaunt skeleton of an ash that had died and toppled lay prostrate upon the carpet of opportunist grass and flower. Bees buzzed lazily among the woodland blooms of high summer. As they made to step into the light, Edric caught his breath and held his brother back. A 14large black bird, its wingspan as great as the boy was tall, glided down from somewhere to their left, landed upon the grass beyond the fallen tree and hopped purposefully for a few feet and began to peck at something. It dawned upon Edric that the sound he had heard was not just the buzzing of bees, but also flies. He had not taken in more than the laden hazel and the fallen tree, but now saw that there was something lying in the grass, some carrion that had attracted both fly and raven. He told himself it would be a roe buck or a fox, but his eyes, now looking with purpose, gave the lie to the thought. The shape was too long, and peeping between the stalks of hedge parsley was a booted foot. Edric’s hold on Agar tightened as another raven flew in, and, to their horror, laughed. It was definitely a laugh, low and rasping, but a human laugh for all that. The boys had been frozen in their fear, holding their breaths until they felt their lungs would burst, but now Agar let out a strangled cry. The nearer raven hopped onto the top of one of the prostrate ash’s skyward-pointing branches. It did not seem particularly afraid of humans, and just stared at them accusingly. Agar felt its beady eyes assess him as another meal. He panicked, and ran, dropping his basket and briefly breaking his handhold with Edric, though the older boy took it again almost immediately to drag him faster than the little legs had ever run in Agar’s seven years of life. The raven flapped loudly behind them and they dared not look back. Their speed made them less footsure, and Edric half-stumbled as his foot caught in a shoot of bramble lying treacherously across their way. As he regained his balance he dared to take a single glance behind, and his thumping heart nearly stopped. A figure clothed head to toe in shabby black, 15the face, if it possessed one, veiled, stood where he had expected to see the raven. He whimpered, and ran faster even though his ankle hurt, and he prayed as he had never prayed before.

It took some considerable time before the two small, ashen-faced boys were able to do more than cry and tremble, even within the comforting hold of their mother. All threshing had ceased in the barn when they had stumbled within, terrified, and it was silent except for the sobbing, with all eyes fixed upon the trio. That something truly terrible had happened to them was not in doubt, and eventually a murmur of ‘wolf’, in a questioning tone, was heard in a man’s low whisper. Herluin the Steward, grim-faced, shook his head. No wolves had been seen in this part of the Wyre Forest since before he had been of tithing age, and, whilst he did not say so, if a wolf had got close enough to the boys that they could be so frightened, it would likely have been stalking them and taken one. The healing woman had slipped out quietly and returned bearing two beakers, and urged both boys to drink. The concoction was nothing more than goat’s milk sweetened with honey, rather than any remedy, but her reasoning was that the very normal act of drinking, and something that was sweet and pleasant, would help calm them so that the full tale could be related. She had also brought the priest, who had been saying Matins in the church.

The adults could only wait, but eventually Edric took a deep breath and managed to speak, though in little more than a whisper.

‘There’s a body, a-lyin’ in the clearin’ by the white tree. We …’ Edric’s voice faltered and he licked his lips, though 16without tasting the sweet residue that lingered there. ‘We saw Her fly down as a raven and peck at it, and then She saw us and we ran, and when I looked back, She was a woman shape again.’ He crossed himself, and many copied the action.

‘“Her”?’ Herluin knew the answer he would receive, but still sought verification.

‘The Hrafn Wif, Master Steward. Afore God I swears it. She must ’ave killed ’im and …’ Edric could not continue and turned his face into his mother’s skirts.

‘Then we must go and bring the body to the church and report the death.’ Herluin’s tone ensured nobody thought this merely a suggestion, but he could feel the lack of enthusiasm almost palpably. ‘I will take six men and that hurdle as you repaired last week, Odda. Four can carry the body and two will have bill hooks in case of need.’

‘But what good is bill ’ooks ’gainst somethin’ that be not flesh and blood and can change shape into a bird and attack us from the sky?’ Odda, thinking that he would be one of those detailed for the party by virtue of having worked upon the hurdle, sounded very doubtful.

‘Because I will come with you also.’ The voice was new. The priest, Father Laurentius, had kept silent and a little apart while everyone was focused upon Edric. ‘No evil will have power over the Cross, and I will bear our processional cross before us.’ The priest did not believe that anything supernatural existed in the wood, but realised that persuading his flock otherwise was a near impossible task, especially in view of the child’s honest declaration. He sounded so calm that it gave the faint-hearted hope.17

‘Thank you, Father.’ Herluin cast his eye over the other men within the barn, and selected those who were the younger and fitter.

It did not take very long to reach the clearing, not least because the hurdle weighed very little, unladen, though it looked very much like a religious procession for some sylvan saint, with Father Laurentius holding the wooden cross from the church before him, though his arms eventually trembled so much with the strain that he had to clasp it less ostentatiously against his chest, and mentally apostrophised himself for the sin of pride in thinking how well he had looked before his parishioners.

The arrival of a group of men making no effort to be quiet, and in fact trying to make as much noise as possible to scare off anything nasty, caused the ravens to rise into the air, up well above tree height, and voice their annoyance by means of throaty croaking. There were now three of them, and they continued to circle above the clearing, to the concern of several of the men below. Herluin stepped forward to advance alongside the priest. From a man’s height it was easy to see that a body lay, face up, in the grass. It was the corpse of a man, and he did not stare at the sky because he no longer possessed even the unseeing eyes of the dead. The face was bloodied and torn, the sockets raw and empty. Herluin crossed himself, and not just because of the horror of the visage. The man was garbed as a knight, and the chances of him being proved English before the Law were almost nil. The murdrum fine would be levied upon the Hundred for the death of anyone of Norman ancestry, and Ribbesford and its steward ‘blamed’ for it. Father Laurentius, 18already intoning prayers for the dead man’s soul, was consoling himself with the knowledge that whoever the knight might be, he was a deeply Christian soul, for his white surcoat was emblazoned upon the left breast with a scarlet cross such as the priest had never seen before, though it was not the only scarlet present, for the cloth was spotted with blood below the neck. He wore a mail shirt beneath the garment, but had clearly not been prepared for combat, for his coif had been drawn back, revealing a head of lightly curling, dark hair still full and untainted by grey. His arms were outstretched, and in his right hand he still clasped his sword. Flies, disturbed by their arrival, rose from the already raven-damaged flesh.

‘Never ’eard of a raven a-goin’ for a man and killin’ ’im, but then what flies ’ere be no normal bird. ’Tis sorcery.’ Odda spoke softly, not just out of respect for the dead, but because he feared the circling ravens were listening, and he crossed himself nervously.

A muttering of agreement and copying of the action showed that his view was shared. Father Laurentius, crossing himself at the conclusion of his prayer rather than in solidarity with his companions, raised a hand to prevent further comment.

‘This we cannot know until he is laid within the church and the body cleaned. It could be he had drawn his sword because he thought he heard a wild animal, a boar mayhap, but in that moment died naturally at God’s calling and what we see is just nature at work after he died.’

‘Then where be the knight’s ’orse?’

‘And would such a man travel without servant or squire?’

These questions could have no answer, but Father Laurentius 19felt they drew minds away from superstition and back to the explicable, so was glad of them.

‘If there is a thought this man was killed by another, the lord Sheriff must be told of the death,’ he declared, ‘and should not a hue and cry be raised?’

‘Waste of time would scourin’ the woods be, Father, since the ’orse be gone, and the threshin’ only part done, but I must go and tell our lord, and bring ’im back from Rock, and then all can be laid before the lord Sheriff, as you says.’ Herluin the Steward was already thinking it would be far better for all this to lie in the hands of William de Ribbesford, who held the manor from the lord of Wigmore. ‘Pity it be that ’e should be otherwhere this day.’

This was agreed by all. Herluin then took the sword from the dead man’s hand, and directed the body to be picked up and laid upon the hurdle. The corpse was stiff, but not so rigid that the outlying arm could not be moved, with effort, to the side of the body, for which he gave up silent thanks. He then placed the sword upon the knight’s chest, respectfully. The four men who were bearers lifted their burden to their shoulders, and the grim procession retraced their steps to Ribbesford and the cool of the church, where they found a board and trestles already laid before the altar, and the healing woman in attendance.

‘I thought it best I be ready to wash the body, Father,’ she murmured, as the corpse was laid upon the board, ‘if’n it be no kin of anyone of us.’

‘A good thought.’ The priest nodded approvingly, and turned to Herluin, who was quietly dismissing the bearers. ‘Will you go to Rock?’20

‘Aye. Five mile be none so far, though up the Long Bank slows a man on foot, but I should be back early after noontide, God willin’.’

‘Let us hope so, indeed. You would not think to take the mule?’

‘Well. I doubt it could bear my weight, and besides, I never rode afore now.’ Herluin was a big man.

Herluin sent the men back to threshing, though he doubted much labour would take place with both news and imaginings to be passed among all, and set off up the track to then follow the ridge line westward. Father Laurentius and the healing woman, Estrith, were left with the deceased, and the priest did not think it beneath him to assist her in removing the weight of the mailcoat from the body. It was then that they made two discoveries.

Herluin the Steward strode back down into Ribbesford alone, and solemn of face. He had spent much of the return journey contemplating what should happen next, since the decisions now lay with him. He was a little surprised that everyone was in the open, and clearly opinions were being exchanged very freely. He could see Father Laurentius making calming gestures with his hands, though without effect. It meant that his approach was not heard until he was well within range for his voice to carry over the others.

‘Does everyone think this another Holy Day when none toil?’ He had their attention, and some folk looked guilty and gazed at their feet. ‘I leaves for but an hour or so and the manor lies idle.’ His disapproval was clear.21

‘But it needs to be decided.’ This was a woman from the back of the group. ‘Should the Hrafn Wif be hunted down to keep us safe in our beds, or at least our children safe when they be out of our sight?’

‘My daughter, there is no proof that the man was killed by other than the evil that men do.’ Father Laurentius’s voice showed strain. He had been making this point for some time. ‘The lord Sheriff’s men must come and decide if the killer can be found, and why he died.’

‘He died ’cos the Hrafn Wif wanted ’is eyes for breakin’ ’er fast.’

‘But we cannot kill ’er if she be no woman at all.’

‘Can the good Father cast ’er away with prayers?’

The three voices spoke at once, and the words tangled in Herluin’s brain for a moment.

‘Quiet!’ It was a command, and was obeyed. ‘Father, you are sure this was the act of a man?’ Herluin had no doubt of it himself, but thought that if the priest said it was so, no blame could thereafter attach to him if folk acted like headless chickens.

‘Assuredly. Come into the church. But where is the lord?’

‘Left Rock yesterday, called by the lord de Mortemer to meet him at Brimfield, and ’twere not clear if they would then both go on to Wigmore. It would take too long to walk all the way there to tell ’im and then to return.’ Herluin was thinking how sore his feet would have been. ‘’Twould be late forenoon on the morrow afore the lord Sheriff could be told, and I doubts ’e would like the delay.’ He followed the priest into the cool quiet of the church. They approached the altar and the now shrouded 22body. Both genuflected and then the priest uncovered the face, calm in the absence of a soul within, with a band of cloth bound about it to hold the jaw shut as the death stiffness faded.

‘The lord Sheriff needs to be informed, as I have said, Herluin, and not just because we have discovered the man died by violence. There was a message hidden close to his chest, for which I think he died, though I have long forgotten most of my Latin beyond the Offices. Do not go to Worcester yourself. I fear I cannot keep them’ – Father Laurentius waved a hand indicating those outside – ‘from wanting to scour the forest, which would be wasteful of time, and, I hope, futile. They will listen to you.’

‘Aye, Father, they will listen, if I has to knock ’eads together for it to be so.’ Herluin looked grim, though he liked the idea that it would not be him having to walk all the way to Worcester. ‘I could send Baldric, I suppose.’ There was a touch of reluctance, for Baldric was one of William de Ribbesford’s men-at-arms, and of the other two one was laid up with a broken hand, and the other had been given leave to visit his dying father in Bridgnorth. Baldric was not a man capable of much thought, but he was strong, looked very intimidating, and was very obedient as long as the command was simple.

‘Can the mule take his weight? If it could not take yours?’ The questions came to Father Laurentius’s lips unbidden.

‘At the pace Baldric can manage, yes. I think so. My worry would be ’im explainin’ it all.’

‘I think the message itself will help with that, Herluin. When I aided Estrith in stripping the body, we found it, as I said, beneath the poor man’s coat of mail, a little bloodstained 23but readable. The lord Sheriff will have clerks who can read every word of it to him.’

‘So you do not think he was killed by the Hrafn Wif, Father.’ Herluin gave a small, twisted smile.

‘No, I do not. Nor did he die at the beak of a raven, for Estrith discovered that a blade had been thrust up under his chin and into the mouth and beyond. The body is still rather stiff’ – the priest grimaced, for Estrith, in her zeal to discover if what she believed was true, had been very forceful in opening the jaws – ‘but you could see for yourself.’

‘No need, Father, if Estrith says it is so and you saw also. Someone must ’ave got up close to do that. Must ’ave been the servant or squire as did it.’

‘But his sword was in his hand, Herluin.’

‘Aye, true enough. ’Tis all too difficult for ordinary folk to unravel’ – Herluin shook his head – ‘and best left for the lord Sheriff, though at Baldric’s pace ’e will not reach Worcester much afore Vespers.’

Baldric was called, and told what he must do and say. After the third attempt at repeating it he got it right, though Herluin and Father Laurentius made him repeat it once again before they finally watched him ride towards the ford with a look of determination upon his slightly vacant face.

‘He will be able to find his way to Worcester?’ Father Laurentius had a sudden worrying thought.

‘I told him to ’ead south, and ’e is able to ask. No more could I do.’ Herluin shrugged, and turned his mind to persuading the rest of the manor folk to get back to work and not go hunting for the Raven Woman.

Chapter Two

Hugh Bradecote, a half-smile on his lips, was watching his lady haggle, in a very polite way, over the price of four ells of fine wool cloth to make winter gowns for their infant daughter and an undershirt for little Gilbert, who was about to attain his second birthday and was exploring the boundaries of behaviour. This meant running his nurse ragged, much noise, and the occasional need for paternal intervention. When this was added to the infant demands of baby Edeva, it meant Bradecote’s hall was far from quiet. He gave thanks that it was so, but it was also good that he and Christina could have this afternoon away on their own. Now that the harvest was safely gathered in, and it looked likely that there would be an excess to sell, he felt that he could relax a little.

He might not normally have escorted his wife as she made her purchases, and instead remained within the castle, but Bradecote was still aware of being less than the lord Sheriff’s favourite vassal. His ‘disobedience’ in Evesham at midsummer, pursuing lines of enquiry where his overlord had commanded he should leave well alone, had very briefly put his tenure as undersheriff of the shire in doubt, and although it was now clear that he was not to be removed from the office, he had 25thought it best to lie low and let William de Beauchamp’s well-known bad temper reduce to a normal simmer. When he and Christina had ridden into the castle bailey to leave their mounts to be stabled, he had not asked whether the lord Sheriff was in residence, and had left immediately, feeling almost furtive.

‘So this where you ’as disappeared to, my lord.’

Bradecote turned, the smile now lengthened, to see Serjeant Catchpoll within three strides of him. The man was very good at ‘appearing’ almost silently, as the thieves of Worcester would vouch.

‘It is not faint-heartedness, Catchpoll, just – caution. I was not avoiding you.’

‘I doubts you could do that, my lord, not if’n I wanted to find you in Worcester.’ It was stated as a simple fact.

‘True enough. I suppose you saw my grey.’ Bradecote’s steel-grey horse was distinctive.

‘Saw its rear end as a lad led it into the stables. I would ’ave caught up with you afore you left the castle foregate, but for the need to give some advice to the guard on the gate who let a stranger walk right into the bailey without so much as a glance, ’is eyes bein’ on a shapely maid with two big’ – Catchpoll paused for a moment – ‘water pails. If I earnt a silver penny for every man-at-arms I showed the error of lettin’ ’is eyes wander when on guard, I would be wearin’ new boots each winter, no doubt of it.’

‘But you told me you liked your boot soles a little thin, the better to feel Worcester beneath you, Catchpoll.’

‘That I did, my lord, so a good thing ’tis those pennies was never given.’26

This interchange having acted as their mutual greeting, Bradecote asked if anything of note had occurred, even if it had not meant him being called in to duty. Catchpoll did not interpret that as an interest in the thefts and minor assaults that were part and parcel of town life.

‘The lord Sheriff ’as stayed back at Elmley mostly, while Worcester’s smell would offend ’is nose these last two months, which means life in the castle ’as stayed quiet but for the lord Castellan buzzin’ about like an angry wasp, just to make hisself feel important. The lord Sheriff came in the end of last month for three days, and when I gave my report, almost waved me away, sayin’ there was far more important things goin’ on. I overheard a messenger bein’ sent to Earl Roger, and the clerk let slip it were not the first these last weeks.’

‘Earl Roger of Hereford? I never heard the lord Sheriff speak much of him before.’ Bradecote looked thoughtful for a moment. ‘But it might be that Earl Roger is concerned about the Welsh.’

‘Hmm, well that ’as always been the case, and they must be keepin’ an eye on discord in England, ready to take advantage when eyes is lookin’ elsewhere.’ Catchpoll’s distrust of the Welsh, collectively, was a very personal thing, but in this case did make strategic sense.

Christina now joined them, her purchase laid over her arm, and Catchpoll greeted her politely, removing his cap and asking if she had struck a good bargain.

‘Indeed I did, Serjeant. Now, do not tell me you have come to take my lord from me.’ She smiled, but was not speaking in jest.

‘No, no, my lady. We was just—’27

The response was cut short as a man-at-arms, slightly out of breath, turned the corner and then dithered not quite sure whether to address the serjeant or the lord Undersheriff. He glanced between the pair and then opted for Catchpoll.

‘Serjeant, you is needed. Underserjeant Walkelin says report ’as been made of the killin’ of a knight in the north of the shire, and the lord Castellan is angry.’

‘Which probably means I should return also.’ Bradecote was addressing Christina more than Catchpoll. She sighed.

‘Indeed, my lord. I will visit Roger the Healer to buy more of that salve he made up for Edeva’s dry skin, and which worked so well, and then I will return immediately to the castle. I am only concerned that you have nothing with you, not even a change of undershirt if the weather breaks and you get soaked.’ She looked at him with wifely concern.

‘I doubt I would shrink, my love.’ Bradecote smiled at her. ‘But if “the north of the shire” means we would be riding in the dark, you have nothing to concern you. I would escort you back to Bradecote, collect all I may need and return to Worcester, ready for an early start.’

‘Then, for once, my lord, I hope you are called further from me.’ She laid a hand upon his arm for a moment, smiled at Catchpoll and flitted away to seek the apothecary.

Underserjeant Walkelin was looking worried. That a report of a killing had come in was not a concern, but that it had been presented to the lord Castellan made things difficult. Walkelin even thought he preferred the lord Sheriff’s bear-like demeanour to that of Simon Furnaux, who disliked Catchpoll and openly 28loathed the lord Bradecote, and made every effort to get the better of both. He was currently making loud complaint that neither was present to do their duty, as though they knew by instinct when such a report might be made. Walkelin escaped the tirade upon the excuse of sending out more men to locate Serjeant Catchpoll in the streets of Worcester, and went to the gatehouse. As the serjeant and undersheriff approached along the castle foregate he gave a sigh of relief, and only just kept himself from rushing forward. That, however, would demean the position of underserjeant, so he stood his ground. Catchpoll, observing him, silently commended his action.

‘My lord Bradecote, I did not know you was in Worcester.’ Walkelin gave a nod as his obeisance and then looked at Catchpoll. ‘Glad I am you was not far away, Serjeant. A rider came in from Ribbesford, upriver in the Forest of Wyre, nigh on the shire border. Two little lads found the body of a man, a knight with the sign of a scarlet cross upon ’is surcoat, in a clearin’ off the track from the ford. The steward sent a man-at-arms from the manor to us, the lord bein’ absent, but the messenger could give no more’n the message itself, bein’ the sort as leaves thinkin’ to others. A vellum message were found beneath the man’s clothin’, when the body were stripped for washin’, and it were sent also. A clerk ’as read it out to the lord Castellan, and only then did ’e send for me, and will not say what lies within it.’

‘He might not choose to tell you, but he will tell me.’ Bradecote looked grim, and strode purposefully into the castle bailey and thence to the hall. Simon Furnaux was ensconced in the high seat upon the dais at the end of the hall, which was 29where William de Beauchamp would sit. Catchpoll thought the man did it to make himself feel more important, since he was not a man who looked naturally commanding. At the sight of Bradecote, Furnaux smiled in an unpleasant way.

‘Ah, my lord Undersheriff. That means I do not have to send for you and delay further.’

Both Bradecote and Catchpoll strove to hide their annoyance, the one for being treated as a vassal and the other for being ignored.

‘It is indeed fortunate, since I will be able to hear exactly what was in the document concealed upon the dead man, and which may be vital to why he was killed and who did it.’

‘Well, I can tell you that—’ the castellan began, but Bradecote held up a hand and stopped him.

‘No. We need to see the vellum itself, and have a clerk read it to us.’ Bradecote felt that finding it too difficult for his very basic reading skills and handing it back to a clerk would look worse than asserting that a clerk would read it from the start. He could see Furnaux dithering. The man liked to know things that others did not. ‘You command this castle in our lord’s stead, but this is about the King’s Laws, in which you have no part. We will hear the document, and then speak with the man who brought the news.’ It was not a request.

‘Very well.’ Furnaux sounded petulant. ‘You’ – he gestured at a servant – ‘go and fetch back the clerk and the vellum I told him to place safely.’ He then glared at Bradecote. ‘I do not think what lies within is for the ears of them.’ He nodded towards Catchpoll and Walkelin.

‘And I do not much care what you think, my lord Castellan.’ 30Bradecote saw the tensing in Furnaux’s hand upon the arm of the seat. Yes, that hit home. There was an uncomfortable silence.

A clerk scurried back into the hall and bowed to castellan and then undersheriff, to the same degree. Clerks, or at least those in the service of the lord Sheriff of Worcester, learnt how to keep their superiors’ displeasure at bay.

‘My lords.’ He left it at that, and awaited instruction.

‘The lord Castellan has heard the contents of the vellum found upon the dead man at Ribbesford and has, correctly, called upon us. He is now free to deal with other … things, but we would look closely at the vellum, and also hear what is has to say and to whom it was sent.’ Bradecote was rather pleased that he had managed to effectively dismiss Furnaux at the same time as asserting his command of the situation, and heard Furnaux grind his teeth. The clerk looked a little nervously towards the castellan, who controlled himself enough to look casual and wave a hand towards the officers of the law.

‘Yes, I have more important matters to attend to. Do as the undersheriff says.’ Furnaux omitted giving Bradecote the lordly prefix, but Bradecote still smiled as the man got up and left, head held haughtily, but the tell-tale hand clasped into a fist. There was silence until he had left the chamber.

‘Now, let us see the thing first.’ Catchpoll’s voice was almost convivial. ‘You never knows what might also be present other than words.’

‘Well, it is obvious enough, for it is bloodstained to the point where some words are no longer readable.’ The clerk sounded very highly affronted that such a precious thing as a document 31should be sullied by a man’s blood. He unrolled what was held in his right hand, for it was a small document, no more than a spread hand’s width in length, and barely as wide. He placed it, reverently, upon a small table beside the sheriff’s seat, smoothed it flat and set a stone as a weight at either end.

The three sheriff’s men came forward, leaning to inspect it and looking as if paying homage to it.

‘A messenger would not normally carry his message concealed within his clothing unless the contents were very private, and possibly dangerous. Whoever killed this man either did not look for it, or was disturbed before he could do so.’ Bradecote was thinking out loud. ‘Read it to us, without haste.’

‘As you desire, my lord.’ The clerk cleared his throat, more as an habitual mannerism than from necessity, and began.

‘“To the lord Hugh de Mortemer, lord of Wig—”’ The clerk pursed his lips and then continued, ‘The rest of that word and the next are unreadable, but obviously “Wigmore” and followed by the standard salutation “greeting”. There are then four or five damaged words, the last of which is most likely “of” and a place beginning “Fari—”. It then continues “we are still resolute in our plan and hope to draw the Usurper Stephen, who ought never to have been crowned, northward, which will allow our Lady’s forces in the south to gather more securely. We rely upon the fulfilment of your treaty with us to begin as if loyal to him and then, when your men form a major part of his force, show yourself for the Just Cause.” There is then a seal’ – the clerk pointed at the bottom of the message – ‘and the name, which reads—’

‘W, I,’ Bradecote could not help murmuring phonetically, 32peering at each letter individually, and the clerk, approving of the attempt but eager to end its tortuous nature, broke in.

‘William fitzAlan, lord of Oswestry, my lord.’

‘FitzAlan fled England after Shrewsbury fell to King Stephen when the Empress mustered her supporters. It sounds as if he has returned.’ Bradecote spoke softly, almost to himself. ‘And Hugh de Mortemer has always been a loyal supporter of King Stephen.’

‘Until now,’ added Catchpoll.

‘Mmm.’ Bradecote was thinking. ‘This gives us a reason why the messenger was killed, but I wonder if the lord Sheriff is aware of this change in allegiance.’ Bradecote looked at the clerk. ‘I want you to write a message to the lord Sheriff and send it with this to his castle at Elmley. Bring ink and write as I dictate.’

The clerk bowed and went swiftly to find the tools of his craft.

‘Always gets difficult when we deals with power that great, my lord. The business of the kingdom – ’tis a big knot.’ Catchpoll pulled a face.

‘Indeed, Catchpoll, and I am sure that this information, if new to the lord Sheriff, will be important, but we must come to an answer, even if thereafter the King’s Justice is not served.’ Bradecote wondered whether he might find himself once again delving where William de Beauchamp would prefer him not to go. The politics of power was complicated, as Catchpoll said. As hereditary lord Sheriff of Worcester, William de Beauchamp gathered the King’s taxes and saw his laws obeyed, though he, and now his overlord, Earl Waleran, had taken a position on the side of the Empress Maud when King Stephen had been captured after the Battle of Lincoln. De Beauchamp was 33performing the difficult feat of keeping close enough to both sides that neither sought his blood. Bradecote did not think his overlord a man of strongly held moral belief, other than in the success of the line of de Beauchamp, and was pragmatic enough to follow whichever side gave most to him and least to his enemies. It was possible that de Beauchamp already knew of this plan, but if he did not, he would not thank his subordinate if he kept it from him.

The clerk returned, and settled himself to write what he was told. Bradecote thought for a moment and then began.

‘Write thus. “My lord, this was found upon the body of a knight at Ribbesford, one bearing a red cross upon his white surcoat, and shown to have been killed by intent. The vellum was sent to Worcester and has been read first to the lord Castellan, in your absence, and now to me. It appears important and so I send it swiftly onward to you. I head north with Serjeant Catchpoll and Underserjeant Walkelin to find out the name of the dead man, if possible, who killed him, and why.” That is the message. I will put my mark upon it, not being possessor of a seal, and you underwrite “Hugh Bradecote, Undersheriff”.’

‘Yes, my lord.’ The quill scratched across the vellum and then paused, and the clerk handed it to Bradecote, who, very carefully, formed an irregular H with three distinct lines, and an approximation of a B. He felt the clerk watching him, no doubt critical of his meagre penmanship, though he commended him out loud.

‘Thank you. Now have this taken straight to Elmley.’

‘At once, my lord.’ The clerk bowed low and left, bearing both documents, and Bradecote sighed.34

‘Now we can speak with the man who brought the news.’

‘And be more like usual, my lord.’ Walkelin was very aware of being at the edge of something so far above his rank as to be beyond imagining. ‘Shall I go and bring him in?’

‘Yes, do that, Walkelin.’

As Walkelin exited, Bradecote looked at Serjeant Catchpoll.

‘I wish this had been a “simple” case of jealousy or greed, Catchpoll. I can see us treading where the lord Sheriff would not have us go in this.’

‘Mayhap, my lord, but sometimes the simple proves the answer after all. We can but pray for it.’

‘Most fervently, Catchpoll. Most fervently.’

The man who entered the hall behind Walkelin looked overawed. He already clasped his cap in both his hands before him and was leaning forward as if caught in the act of bowing.

‘This is Baldric, from Ribbesford, my lord.’ Walkelin announced the man, who raised his round and slightly vacuous face to nod agreement to the statement and then lowered his gaze once more.

‘You have had a long ride, Baldric.’ Bradecote tried to begin without making the man feel more nervous.

‘Set off ’bout two hours after noontide, my lord. I could not ride faster, bein’ a bit big for the beast.’ Baldric addressed Bradecote’s feet, and the undersheriff wondered if his lord was a hard taskmaster.

‘Then give me your message as you gave it to the lord Castellan.’

‘As best I can, my lord.’ Baldric did not think he could match 35the words exactly. He stumbled through the clearly memorised message, which gave no more than what Walkelin had passed on. At its conclusion he gave a sigh of relief.

‘So that was the report itself but what can you tell us?’ Catchpoll took over the questioning, seeing that Baldric was so overawed, or possibly tired.

‘’Twas not me as found the knight. Two little lads went foraging for cobnuts, and went where they was told not to go, up where the Hrafn Wif lurks.’ Baldric shuddered, and crossed himself. He was one who believed in the malign presence as firmly as a child. ‘Many a time they ’as been told not to go there, but lads will be bold where wiser folk would be cautious.’ He said this with a shake of the head and a sigh. ‘Seems they came to a clearin’ and saw a body and she flew down, laughin’, and pecked its eyes out, and they ran away. As they ran away they looked back and saw a black figure among the trees, watchin’, so she ’ad changed shape again. Our lord says ’tis all foolishness, the Hrafn Wif, and shows no fear to go up there, but this proves she kills, and for pleasure.’