11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

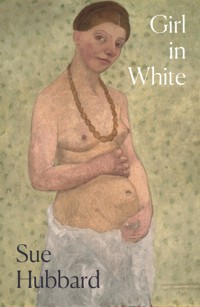

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'Beautifully-written, and highly evocative of the remote Lincolnshire landscape, the Second World War and the two people whose loneliness brings them together for a life-changing time' Amanda Craig 'Compelling and beautifully intimate. A classic piece of storytelling' Toby Litt 'A haunting and lyrical novel' Maggie Brookes, author of The Prisoner's Wife In the depths of wartime, a friendship takes wing Freda is a twelve-year-old evacuee from the East End, sent to live with a farming family deep in the lonely landscape of the Fens. Philip is an artist and a conscientious objector, living in a remote lighthouse on the shores of the Wash. The two outcasts come together amid the wild beauty of the wetlands, beneath skies filled with migrating birds and crisscrossed by Nazi bombers. As the world is consumed by war, they form a friendship that will change the course of both their lives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

1

PRAISE FOR SUE HUBBARD’S NOVELS

‘A triumph… Masterly, moving and beautifully written’

FAY WELDON

‘I recommend this haunting book’

JOHN BERGER

‘Beautifully-written and evocative’

AMANDA CRAIG

‘A writer of genuine talent’

ELAINE FEINSTEIN

‘Lyrical, highly visual and beautifully observed’

JOHN BURNSIDE

‘A beautifully-written meditation on love, loss and grief’

IRISH INDEPENDENT

‘Hubbard deserves a place in the literary pantheon near Colm Tóibín, Anne Enright, and William Trevor’

AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

‘Gently absorbing… Wistful but never morose’

DAILY MAIL

2

3

5

I cannot picture what the life of the spirit would have been without him. He found me when my mind and soul were hungry and thirsty, and he fed them till our last hour together.

A Backward Glance, edith wharton

Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless?

Jane Eyre, charlotte brontë

6

Contents

Acknowledgements

My special thanks are due to Stephen Duncan for his cajoling, prodding and persistent support to get this book written. To Marianne Lewin and the late Linda Rose Parkes for reading the manuscript, and Annie Wilson for her eagle-eyed corrections. To Doug Hilton and his wife for making me welcome at the lighthouse and pointing me in the right directions. To Peter Scott’s daughter Dafila for having me to stay and talking about birds, and to those at Slimbridge who educated me about geese, and to the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig where much of this was written.

I would also like to thank Captain Patrick Jary, Harbour Master of King’s Lynn, for ‘talking’ me out of the River Nene into the Wash, and my son, Ben Hubbard, for walking the fifteen lonely miles from Peter Scott’s lighthouse to King’s Lynn. 8

A Note from the Author

In 1933 the ornithologist and wildlife artist, Peter Scott, took possession of a deserted lighthouse situated on the mouth of the River Nene on the Wash. It was in this isolated spot that he created his first bird sanctuary. In 1941, his friend the American journalist and short-story writer, Paul Gallico, published a children’s novella, a parable on the regenerative power of friendship and love, The Snow Goose, inspired by Scott’s lighthouse, which he relocated to Essex for his book.

In this novel, I have developed the bare bones of Gallico’s tale into a story for adults, and returned the narrative to the remote corner of Lincolnshire where Peter Scott’s lighthouse stands.

I have kept the original names, Fritha and Philip Rhayader, from The Snow Goose, but I have changed the species of the bird they care for. Pink-footed geese breed in eastern Greenland, Iceland and Svalbard. They are migratory, wintering in north-west Europe, especially Ireland, the Netherlands, western Denmark and Great Britain. The snow goose in Paul Gallico’s novel is native to North America, and is rarely found in these islands. 10

Part 1

1939

12

13

Iwas twelve when i was sent to that cold place. I could never have dreamt that anywhere so lonely existed. In my mind’s eye it was always cold, though I arrived in September. A hot day, the sort of day for a picnic not a war. From the stuffy train we could see gangs of women in the fields dressed in old sun bonnets and aprons, weeding rows of potatoes and stacking bundles of hay. Land Girls in khaki drill. And above, the tiny dot of a skylark hovering, soaring up-up-and-up until it finally disappeared into the high wide blue. But still, what stays with me are the winter flurries of sleet over the tidal estuaries. The whalebone-coloured skies and frozen tidal creeks. The eerie honking of wintering geese as they lifted their strong-muscled necks and angel wings in the mist above the reed beds and frosted fields. Hands and toes chapped raw with chilblains. No, after Bethnal Green with its crabbed back-to-backs, its soot-blackened tenements, bustling markets and noisy pubs, I could never have dreamt that such a place existed.

Very few people lived there. A clutch of tenant farmers and poachers. Local oyster catchers plying their ancient trade. It was known as Black Fen. Black for the peaty soil and melancholy of the place. For its dark, hidden histories. A flat, flat land extending as far as the eye could see, with nothing to help a stranger 14 distinguish one stretch of sugar beet from another monotonous field of swede or celery. With few hedges and even fewer trees, the bitter wind swept in from the Wash gathering up topsoil, depositing it in cottages, blocking dykes and ditches. Chilling the bones. The Fen blows they called it. Murky as London smog, it filled lungs, clogged eyelashes and turned mucus black.

Hardly a day goes by when I don’t think of that place. I knew only that it was far from home. Far from my beloved nan and the small world I’d grown to know during my twelve years living above that cramped hardware shop in the East End. Once, when wool was in demand, the Fens had been one of the richest areas in England. In medieval times exports from the Lincolnshire town of Boston were booming and the town paid more tax than any other except London, but by the time I was sent there, the area was down-at-heel, neglected and forgotten. Ancient villages and flint churches sat lonely as widows among the sad, flat fields of potatoes and sugar beet. When the local landowners first drained the marsh, the fen dwellers were bitterly opposed. Worried the drainage systems would destroy their fisheries, stop them catching the eels that teemed in their thousands in the waterways. Concerned that the reclaimed land would be given to the men who’d carried out the work, not back to those who rightfully owned it. Dykes were breached. Ditches filled, the peat shrank and water levels rose, so gradually the canals became higher than the land. Windmills were built to scoop up the water.

Now the dykes are several feet above ground.

With few roads it became a refuge for the lawless and the feral. Even the Romans thought the place ungovernable. Found 15 themselves outwitted by the cunning Fen folk who strode across the marshes on tall wooden stilts. A skill they failed to master.

The Great Marsh. A place between somewhere and nowhere. Created by the gradual build-up of mud from the rivers that flow into the Wash. Neither land nor water, constantly flooded by salt tides. One of the last wildernesses in England. Grass and reeds, half-submerged meadowlands, mudflats and saltings appear stitched to the huge skies and wide expanse of open sea. And everywhere there are birds. At first, I couldn’t tell them apart. But slowly you taught me their names. Teal and wigeon. Redshanks and curlews. Terns and gulls. Greylag and brent geese. The black-tailed godwits and dunlin that swirled in their hundreds of thousands between their high-tide roosts and food-rich mudflats.

When I arrived, a shingle and shell embankment, covered in yellow horned poppies, formed a bulwark against the ever-encroaching sea. It’s still there but breached by many tides. The shape of the land has changed over the years. Bits have fallen away, become silted over. Where pink-foot and little tern used to fish, cows now graze. And, at low tide, the deserted lighthouse appears like a lost thought. Once a beacon shining out across the North Sea, warning ships from Jutland or coal vessels making their way down south from Newcastle of dangerous tidal currents and sandbanks, its rafters, now, are inhabited by bats and nesting owls. Its lantern dark.

16 I don’t live in that lonely place now. A lot of water has flowed under a lot of bridges. Now I’m old. My life mostly behind me. I don’t expect anything else much to happen. I live each day as best I can. Try to be positive, despite the sciatica. Inside, I’m the same person I’ve always been. That’s the thing. The heart remains unchanged. It’s just the body that ages. But the longing remains. The longing for those moments all those years ago in that place where sea and sky met. Now the old woman others see bears no relation to the young girl I once was and still, inside, often feel myself to be. Mostly I’m invisible. Voices change when people speak to me. I call it their ‘wallpaper voice’. Flat and even, it papers over the cracks. No one really wants to know how I am, even if they bother to ask. Wrinkles have a way of making you disappear one line at a time. I’m just the lady in the green cardigan and sensible shoes. But life has its blessings if you choose to count them. And I have my story to tell. Each of us does. All of us are simply trying to make sense of a world we don’t quite understand. Dipping our toes into that black box of memories to answer those nagging questions: the whats, the hows and whys.

But I’m lucky. I have my health—apart from the pain in my leg—and mostly my mind. Though what happened seventy-five years ago is easier to recall than where I left my glasses. When it’s fine I go to Victoria Park, where I used to play all those years ago as a child, and sit on the bench. Watch the toddlers eating ice creams, the young boys doing tricks on their skateboards, the swans on the lake floating past in flotillas. Swans are the romantics of the bird world. They mate for life. I’ve always liked birds. There’s a robin that comes 17 to the ledge outside my bedroom window. I save him my breakfast crusts. Robins are very territorial. He thinks he owns the place.

I like to watch the spray from the fountains make rainbows on the artificial lake. Sometimes I take my battered copy of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury with me in my handbag and sit there with a cup of tea. The book’s very worn now. The spine coming apart. I like Keats and Edward Thomas. I’m not so keen on more modern stuff. I enjoy rereading the poems I learnt as a girl, and know many of them by heart. As a child, Victoria Park was the only green space I knew. I’d never been to the country, except on a coach trip with Mum to Southend where I sat on a miniature clockwork train that ran round and round the edge of the municipal garden with its flower clock planted with golden marigolds, where fat-bottomed ladies in white skirts played bowls. I remember I had a strawberry cornet that dripped all down my blue cotton dress, and a donkey ride. By the time I got home, my bare shoulders were so red and raw that Mum had to smother them in pink calamine. Though that was the seaside, not the country. But still.

In summer, while Mum was minding the shop, Iris and I’d go to the park. Tuck our dresses in our knickers and paddle in the ponds, daring each other to go up to our knees without getting our clothes wet. We knew we’d cop it if we did. Sundays we’d hang around the men on their soapboxes. We hadn’t a clue what they were on about as they waved their arms, spat and barked about socialism and fascism. But we thought they were funny. There was a man in a torn mac with a sandwich board that said, ‘The End Is Nigh’. Another who claimed he 18 was a prophet inspired by the Holy Ghost. But they locked him up in the loony bin.

During the war, the park was closed to the public. Used as an ack-ack site to target the Luftwaffe’s bombers looping back north after an attack on the docks, and a holding camp for foreign internees was set up just beyond the tennis courts. Even Signor Giuseppe, who ran the ice cream parlour in Bethnal Green Road, where he made his own ice cream with real lemons, got put in there before being sent to the Isle of Man. Another corner was used to launch barrage balloons, and another turned into an allotment. The railings were melted down for guns, and an air-raid shelter was built near St Mark’s Gate. But Mum would never go there.

You won’t catch me doing my business in a bucket in front of the neighbours. I’ll take me chances with the Hun, thanks very much, and keep me knickers to meself.

I was born into a family of shopkeepers. My grandfather’s name, D.W. Cooper, was written over the door in gold letters. The D.W. for Donald Walter. Though towards the end of his life everyone just called him Duck. I still have an old photograph of him with his big moustache, standing outside on the pavement in his white apron among the besoms and brooms, the shovels and galvanized baths. The buckets hanging above the doorway in the cobbled street. Coopers of Bethnal Green sold balls of string, packets of starch and Reckitt’s Blue for whitening the weekly wash. Laundry dollies, fuse wire and nails by the ounce, which were weighed out on the brass scales and 19 poured into brown paper bags like boiled sweets. Duck died when I was four. So the shop was run by my nan and mum. A family of women. Our lives were lived in the tiny dark room behind the shop we called the scullery. When I was small there was a black range with two ovens on either side, surrounded by a fender with a padded seat. But when Duck died, Nan got two men from Mile End to rip it out and put in a modern one with beige tiles. The new gas cooker—at least new to us—stood behind the door opposite the old Belfast sink with its hairline crack and dripping cold-water tap. Pushed against the wall was the table covered in a checked oilskin that you had to squeeze past to get to Nan’s armchair squashed between the fireplace and window. And on the high shelf, beside the print of Sir John Everett Millais’s Bubbles that Mum got free with Pears soap and hung in the gilt frame she found in Brick Lane, was our mahogany radio. The one with a mesh grill that Nan bought with the insurance money after Duck had gone. Mum had to ask Mr Baker from next door to fix up the wire aerial or it just crackled and faded in the middle of a programme. We always listened to the six o’clock news and Mum loved the Glenn Miller Orchestra. She liked to sing ‘Doin’ the Jive’ as she sashayed round the kitchen getting the tea. Outside the back door, a flight of stone steps led down to a concrete yard, not much bigger than the scullery, surrounded by a high wall. At the far end was the lavatory. It was dark and cold, and you had to stand holding the chain until it finished flushing or the water just stopped.

20 Since my dad, Sid, had upped and left with Vera from the bookie’s, it had just been the three of us. I couldn’t really remember living with Dad. Though I dimly recollect him coming home smelling of the Black Horse, singing ‘It’s De-Lovely’ in an American accent, pretending to be Eddy Duchin. He’d be in the Horse till closing time, wisecracking with his mates. Small-time crooks and East End stallholders. Peeling a ten-bob note from the wad in his back pocket, placing illegal bets on the gee-gees and the dogs.

Scottie had two winners today, missus, he’d announce, rolling into the kitchen with his mates, the worse for wear. Mum was always missus. Or, if he was in a lovey-dovey mood, Doll.

Don’t bleedin’ tell you nothing about all his losers, though, does he? she’d answer tight-lipped, slamming the bedroom door and telling him to sleep on the sofa. After that, he’d settle at the kitchen table with his cronies for a game of whist and a couple of bottles of Burton Old. But he always managed to charm Nan. Kissing her on the cheek and asking: How’s my gal? when he came in the door.

He and Mum met in a dance hall in Clacton-on-Sea. A smooth talker, my dad, he soon had Mum pregnant. A commission agent’s clerk—which was just a posh way of saying he worked in the bookie’s—he always looked sharp. Brilliantined hair and a double-breasted from Harry Cohen’s in Petticoat Lane. After he went with Vera, he always sent me birthday cards with my age embossed on the front in golden numbers. Once he took me to London zoo. I remember the tigers and throwing fish 21 to the penguins who walked like Charlie Chaplin. Riding on a little wooden seat with some other kids, high up on a swaying elephant, terrified at being so far off the ground. My first toffee apple.

I thought Dad was wonderful because he did tricks. Fished out coins from behind my ear or from underneath an empty handkerchief. Made an ace of spades vanish into thin air. He was a born showman, a raconteur, a wide boy, but he loved me. How do I know? Because when he shaved, he’d stand in his string vest, a towel thrown over his shoulder like a prize fighter and pull funny faces at me in the small, fogged-up mirror. Push up a piggy-nose to reach that bit above his top lip, sticking out his tongue from the foam beard lathered over his cheeks with the big bristle brush, to make me laugh. And when he got back from the pub, he’d tiptoe across the creaking landing and climb onto my narrow bed. Shove me up against the wall with his sharp elbow and, in a beery whisper, tell me about The Little Mermaid or Sleeping Beauty. Stories where he always gave the heroine my name. Freda.

But after he went with Vera, Mum wouldn’t have him back in the house.

Not long after I was sent away, he was called up. At the time I didn’t know where. He was drafted into the Royal Army Pay Corps, the unit responsible for administering all the army’s financial affairs. Stationed in Foots Cray, near Sidcup, there was always the chance for the odd scam. Many years later, going through his things after he’d passed away, I found a photograph of him in uniform. It seems he toyed with the idea of deserting. Happier to face prison, with the guarantee 22 of three hot meals a day and a warm bed, than the Jerries. Though that was never a real possibility in the Pay Corps. The most dangerous thing he was likely to encounter was an angry sergeant major.

It’s bad enough being your fancy woman, Sid, Vera protested. But I’m buggered if I’m going to be a deserter’s fancy woman. You bloody well go and do your duty.

In many ways the Pay Corps suited him. Got him away from women. He liked a kiss and a cuddle, but women were always wanting things. A bob for this. A tanner for that. Always wanting to know if you loved them. Foots Cray became his fiefdom. When rationing started, he could get his hands on whatever you fancied for a few readies. Extra tea. A pat of butter. A jerrycan of petrol. With a bit of wheeling and dealing, he could conjure up ciggies and nylons, a bottle of Johnnie Walker, a tin or two of corned beef. Even French perfume. Spivs, runners and ticket touts. They were his friends. But looking back, I realize, he was already slipping from my life.

I never appreciated that we were poor. But we must have struggled. Mum was still a pretty woman; though her looks were beginning to fade, she still had thick auburn hair that fell in natural curls. But like most East End women over thirty, her face was beginning to line and the first grey hairs appear. She was always trying ‘something new’. Egg-white face masks. Pond’s Cold Cream slathered across her cheeks and forehead at bedtime, her hair set in tight pin curls under a rayon scarf. 23

You don’t look a bit like your mum, people would say if we stopped and chatted when out shopping in the market. By which they meant that with her thick wavy hair and small waist, she was pretty. While I, with my lank pudding basin, my scrawny arms and legs, was not.

I often wondered if it was my fault that Dad left. If I got in the way. Stopped Mum from spending nights out with him at the Black Horse. Prevented her from having a new dress or that coveted compact of Rimmel face powder she so wanted because she had to clothe and feed me. She was a romantic and liked nothing better than an afternoon at the Gaumont with a box of Milk Tray, watching Bette Davis play Jezebel. That headstrong young Southern belle who wore a scandalous red dress to the local ball. Mum cried at the bit where Jezebel’s sweetheart left to marry a respectable northerner. Mum always wanted a Prince Charming to come and save her after Dad left. But he never turned up.

She longed to be fashionable but didn’t have the means. Up each morning before I left for school, she’d slip her pinny over her cotton dress and go through to open up the shop, hanging up the mops and dusters in the street outside the front door. The galvanized buckets and bristle brooms. The rubber sink plungers. It would be Nan scrubbing the egg-stained plates or knitting by the gas fire when I got home from school. Her big girdle and lisle stockings airing on the wooden kitchen maid. Her shins mottling in the heat.

If I close my eyes, I can still hear the clack of her needles. Feel the cold windowpane against my cheek. It’s winter and I’m staring out into a brown pea-souper, watching the rain 24 condense into greasy drops on the glass, placing bets with myself to see which will reach the bottom first. I’ve been arranging the cigarette cards Dad saves for me into sets, hoping he might turn up. Not the footballers. I didn’t like those. I swap those at school for Cottage Garden Flowers: blue hollyhocks, pink roses and dahlias. Or Film Favourites: Clark Gable, Jean Harlow and Errol Flynn. Though I never could find Bette Davis.

The day before I was sent away to that cold place, Iris and I went to look at the burst water main in Roman Road. Iris was my friend. My only friend. Her mum worked in the fish shop, so her clothes always smelt of coley.

Ooh it’s like a fountain, she squealed, her frizzy red curls bouncing up and down as the water gushed from the pipes.

When we peered into the hole the workmen had dug, I noticed a single sandal dropped in the mud. It upset me, that lost shoe. Made me think of Nan alone in the dark back bedroom. Until recently she’d be waiting for me every Friday after school at the scullery table with the big yellow mixing bowl and a jar of plain flour to make pies and jam tarts for the weekend. We’d sift the flour through the wire sieve, rub in cubes of margarine, add water and salt, then knead the dough with our cold hands. She taught me how to roll the pastry on a floury board with the wooden rolling pin. Cut out circles for jam tarts with the rim of a teacup. Make gooseberry and apple pies, crimping the edges between thumb and forefinger, then cutting little pastry leaves to decorate the top, before brushing them in egg white with the special pastry brush so the crusts turned golden brown. I’d 25 practise peeling the apples so the skin came off in one go and I could make a wish. And while the pies were in the oven, Nan would sit in her special chair, her veined legs propped on the wooden stool, her red hands resting in the floury lap of her apron, the thin gold wedding band cutting into her swollen fourth finger. When the pies were ready, we’d cut a slit in the top to let out the steam.

That day, after visiting the broken water main, Iris and I went to the sweetshop, sauntering home past the kosher butcher, the coal merchant and the barber’s red-and-white-striped pole, sherbet lemons exploding on our tongues. When I got in Mum was in the scullery talking with the doctor.

There’s nothing more to be done, I’m afraid, he was saying in a voice like the vicar’s, rocking backwards and forwards on the worn lino in his shoes with the polished toecaps.

I couldn’t listen and ran upstairs to the back bedroom where Nan was propped up against the bolster in the iron bedstead like a small grey-haired child. The room was dark and damp, filled with a fug of coal dust and Wright’s coal tar soap. A cup of half-drunk beef tea was sitting on the bedside table and, even though it was summer, a fire was burning in the grate. Above, on the mantlepiece, beside the row of ivory elephants that got smaller and smaller right down to the baby, was a photograph of Duck before he left for the Somme. And, at either end, two plaster horses reared up on their hind legs, their wire reins held by a pair of naked ladies with roses in their hair that Duck had won in a Test Your Strength booth on Clacton pier when he 26 and Nan were courting. I climbed onto the bed beside her, but she felt so shrunken and small under her winceyette nightie that I started to cry.

Now lovey, no fuss, she said, kissing the top of my head. You’re a big girl now.

I shake the rain off my umbrella, put it in the stand by the door and settle at a table that looks over the fountain. If the weather clears, I’ll walk round the lake. I try to do it twice a week. But I’m slow now. I always start at the main entrance on Sewardstone Road. Near the wrought-iron gates with their stone Dogs of Alcibiades. I like watching the seasons change. The crab-apple blossom coming into bloom and the lilac. The ripening conkers. Small details that keep me anchored in the present. Often, I doubt my memories that belong to another century. There’s no one left to corroborate them now.

Number five?

A pot of tea and a scone. A dish of strawberry jam. One of my small indulgences is to come to the park café. I like to sit here and write in my journal. My memory isn’t what it once was, so it helps me to remember. Enjoy, says the girl, as she puts down the tray. I’ve not seen her before. She has a blond ponytail, heavily made-up eyes and is wearing a boy’s checked shirt and jeans. There’s a small swallow tattooed on the inside of her wrist. I can’t get used to these young girls having tattoos. In my day it was only sailors and criminals. You never saw them on a woman. She’s pretty and I wonder if she has a sweetheart. Where she’s from. Poland? Lithuania? A migrating bird blown 27 off course. This part of London has always been a melting pot. Jews, Bengalis, Turks. Now Romanians and Albanians. There are few left, like me, who were actually born around here. Houses that once held three families sharing an outside toilet have been done up with expensive bathrooms and IKEA kitchens by couples whose children have names like Noah and Mia. I wonder, where have all the Dorises gone?

The room I live in now looks out onto a small garden. Sparrows, so common in my childhood, are rare. Though there’s the occasional tit or blackbird. The other day one flew in through my open window and crashed against the glass in a panic before I could help it back outside. On warm days, the carers bring the less mobile residents out in their wheelchairs to sit in the sun. A tartan rug tucked around their knees, their liver-spotted hands fluttering like butterflies in the spring warmth.

I don’t mind the place. You hear stories about homes like this, but the staff are very kind. There’s not an English girl among them. Gloria’s from the Philippines. Beverly from Guyana. Svetlana from Tbilisi. Oh, and there’s an Irish girl from Leitrim, Bernadette, who’s going home soon to marry her childhood sweetheart, Declan, and run a B & B. Bernadette likes to chat. I know her parents own a farm, mostly dairy cattle, and that she has three brothers, and a sister who is a district midwife. Bernadette’s the second youngest and wanted to be a nurse too, but there weren’t the funds to send her to college.

Why are you here? they ask, as they plump pillows and fill water jugs. Why aren’t you with your family?

But I’ve a comfy single bed and the curtains are covered with yellow primroses. There’s a matching bedspread and a 28 blue crocheted cushion on the chair where I sit and read and watch the birds. I still enjoy reading, though my eyes aren’t as good as they once were. Mostly I like the classics. Rereading The Mill on the Floss or The Mayor of Casterbridge. Books I discovered as a young woman when training to be a librarian. Outside my window there’s a laburnum. It seems something of a trick of nature that such a pretty tree, with its cascade of golden clusters, should be so poisonous. I also have my own dressing table. We could bring one small piece of furniture with us to make it feel more like home. It’s where I keep my trinket box with my mother’s wedding ring. Her marcasite swan brooch. The amber beads I never wear because they need restringing. I don’t have much to remember her by. There are other odds and ends, too, that I can’t bring myself to throw away. A spool of negatives. Old tickets. A single white feather. Life soon becomes reduced to a pile of ephemera.

Why do I keep these things? These bits and bobs, meaningless to anyone other than me. Because they take me straight back, provide tangible evidence of what really happened. Proof that everything isn’t just a figment of my overblown imagination.

When I’m gone there’ll barely be anyone to remember me. I don’t have children. Books have been my life. I enjoyed being a librarian. There’s something comforting about the Dewey decimal system: 100 for philosophy and psychology, 200 for religion and mythology, through to social science and folklore, dictionaries and encyclopaedias. I liked the fact that each book has its own position. Its own shelf. I prided myself on my card index system. Blue for fiction. Yellow for history. Pink for romance. Each card housed neatly in its small wooden 29 drawer with a brass handle. Typed with its category number, author and title. That, of course, was long before computers. It’s all different now. And there are far fewer libraries. They all seem to be closing. I don’t think people read so much any more, what with all these new-fangled electronic games. There are too many other distractions.

In my day, all sorts came to the library. Men looking for jobs in the small ads. Down-and-outs wanting shelter from the rain for a few hours. Children in search of the new Enid Blyton. I lived on my own, so liked the company. Helping people find a book on the Tudors or instructions on how to make a rabbit hutch. You’d get to know the regulars. The lady from the wool shop who came in every week for the new Mills & Boon. Her favourite, I seem to remember, was In the Name of Love by Guy Trent. She took that one out many times. The lonely old gentleman who liked Greek myths. I particularly enjoyed the quiet after closing time when everyone had gone, when I was there alone, making sure all the books had been put back on the right shelves. The magazines and newspapers folded and placed in the correct racks. It gave me a sense of satisfaction when I turned the lights out and locked up, that everything was shipshape. Ready for the next day. In truth, I suppose, I’m quite solitary. Happiest with my own company. It’s always felt easier that way. But working with books gave me a window onto other worlds, other experiences I’d never otherwise have had.

On the mantlepiece, above the gas fire, are my photographs. A faded black-and-white snap of my parents on their wedding day. My mother in a little cloche hat with a veil, holding a bunch of forget-me-nots tied with a white ribbon. Dad raising a toast. 30 They are in the Black Horse. Mum smiling and looking happy. And then there’s one of me as a five-year-old, sitting cross-legged in the front row on the playground tarmac. I remember how the photographer ducked behind a little curtain before the flash of his big tripod camera went off. Sitting just behind me, her hands on her knees and her hair braided in two plaits and twisted over her ears like earphones, is Miss Wilson. I liked Miss Wilson. She had sticky-out teeth but was kind and smelt of lily of the valley. Her fiancé died in the Great War and, like many of her generation, she never married but made some sense of her life teaching and singing in the local choir. She must be long gone by now. Next to me is Iris, one eye of her glasses covered with thick Elastoplast to correct her squint. I wish I knew what had happened to her. She married a Scot at the end of the war and went to live in Glasgow. Had three children. But then we lost touch.

I do so wish I had a photograph of you. Though I still have the little Bakelite-and-glass snow globe. A child’s toy, more than seventy years old. You gave it to me that Christmas, wrapped in blue paper covered with little gold stars and I kept it under my mattress. A secret. It was the most precious thing I’d ever owned. When I shook it, a blizzard swirled over the thatched cottage, turning everything white. I imagined a happy family huddled by a crackling fire. A shimmering Christmas tree and, underneath, presents tied with coloured string. A plum pudding boiling in muslin on the stove. Outside, the iron-hard fields of the Fens. Kale and cabbage dusted with rime. Frosted sea holly. 31 So much is considered beautiful because it’s valuable, but my little snow globe is quite worthless, except for the memories it conjures.

Snow shrouds the dirty and broken. The things we’d rather forget.

I also have your notebook and the painting of the young girl with watchful eyes. It hangs above my bed. Her skin’s so white you can almost see the blue veins beneath it, and her fringe is frayed and ratty, as though she’s taken the scissors to it herself.