9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

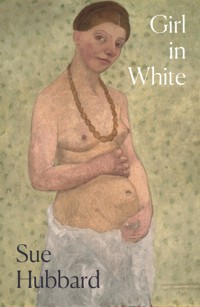

Paula Modersohn-Becker was a pioneer of modern art in Europe, but denounced as degenerate by the Nazis after her death. Sue Hubbard draws on the artist's diaries and paintings to bring to life her singular existence, her battle to achieve independence and recognition and her intense relationship with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke.Not only do we discover Paula's vibrant personality and rich legacy of Expressionist paintings, but also come to understand something of the corrupted ideologies of the Third Reich. Written with the eye of a painter and the soul of a poet this moving story is a meditation on love, loss, memory and, ultimately, hope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise for Sue Hubbard and Girl in White

‘A triumph of literary and artistic understanding, a tour de force: Masterly, moving and beautifully written. Hubbard goes where few dare go, and succeeds. You are the less for not reading it’

fay weldon

‘A writer of genuine talent’

elaine feinstein

‘Haunting’

john berger

‘Hubbard deserves a place in the literary pantheon near Colm Toibin, Anne Enright and Sebastian Barry’

american library association

Girl in White

Sue Hubbard

For Izzy, Freddie and Amelie

The work of Paula Modersohn-Becker is not much known in this country. As a painter she was far ahead of her time and deserves a place alongside the likes of Gwen John and Frida Kahlo. I have broadly followed the events of her life and, although some incidents are fictitious, my aim has been to give colour and texture to her singular existence, as well as to place her against the background of her times in Germany where, after her death, her work was denounced as degenerate by the Nazis. Her intense relationship with the poet Rilke, her struggle to find a balance between being a painter, wife and mother, are issues that many women can still relate to today. The role of her daughter, Mathilde, is one of pure imagination. I chose not to know anything of her real life and used her to provide a narrative perspective. I am grateful to her, and hope that she would have approved. But above all my thanks is due to Paula; for her paintings and for her diaries. Without these this book would not exist.

In art one is usually totally alone with oneself.

paula modersohn-becker, Paris, 18 November 1906

CONTENTS

MATHILDE

…And then it begins to snow. As I step from the bus large white flakes land on the rim of my felt hat, soak my lisle stockings and seep into the leather soles of my new T-bar shoes. It’s the first fall of the year and has come too early. I should have dressed more sensibly, but hadn’t expected this turn; nothing is normal these days. That’s why I had to come now. Soon it might not be possible. I’ve heard the hectoring tones over the airwaves, seen the crowds gathering in the streets; the banners, the torchbearers and the flags.

I can smell it in the air, another war.

It terrifies me, but I can’t think about it now, about what it might mean for the future; mine and this country’s. Today’s my birthday. November 2nd, 1933.

And what else should I do to celebrate the day of my birth other than come back here to visit my mother? Who else should I turn to with my broken heart? On the bus from Bremen I got out my little diary with the black calf cover to count the weeks again, just to be sure. But there’s no mistake.

I thought feeling sick was simply a symptom of grief. It never occurred to me, naïve as it sounds, that there might be some other reason. I’m not even sure when it happened. But this simple fact changes everything. It gives me a reason to go on. After you left there was nothing to live for. I wish more than ever that my mother, that Paula, was around. I’m sure that she’d have understood. Maybe coming here I’ll feel a little closer to her, be able to make some sense of everything that has happened.

As I hurry from the bus, turning up the rabbit-fur collar of my coat against the flurries of damp sleet and pulling down my felt hat, I pause by a clump of tall birches, uncertain where to go. I’ve pictured the village so often that now I’m actually here, I feel disorientated. From where I’m standing I can look out over the open landscape at the paths and canals that criss-cross the dark moors. The sky is the colour of dishwater and low clouds lie in a heavy blanket over the horizon. I make my way along the cobbled pavement past the cottages with their high thatched roofs and whitewashed facades latticed with black crossbeams. A few lights glow in the afternoon dusk and I stop outside the gate of Heinrich Vogeler’s Barkenhoff, basically a farmhouse like the others, though it’s more isolated in its large garden. I know it, of course, from his painting: the green gate and high windows half hidden by pink rambling roses. I’ve always known it. My father, Otto, bought the painting when we moved away the year after my mother died. I grew up with it, knew the names of all those sitting on the terrace that summer evening, talking and playing music. On the left is my mother, with my father, Otto, and Clara Westhoff-Rilke. Vogeler’s wife, Martha, is standing on the steps in the middle of the picture flanked by two bay trees. She’s wearing a green satin dress with a white lace collar and leaning against the balustrade, holding a large wolfhound on a leash. On the other side of the terrace are Heinrich Vogeler and his brother Franz, playing a flute. Someone else is playing the fiddle. A group of young friends in a garden on a summer evening seated among roses and potted pink geraniums, reciting poetry, making music, and dreaming dreams.

But when I reach the actual house it looks nothing like the painting. It’s rather run-down and a group of whey-faced boys with cropped hair and chapped knees are planting potatoes in the garden. I make my way in the flurrying snow through the village, up the sandy path to the church with the white wooden clock tower. It was here that my mother Paula and her friend Clara climbed the belfry one balmy August evening and rang the bells out over the sandy mound of the Weyerberg. Thinking there was a fire the frightened villagers ran from the houses clutching their pots, pans and brooms, still dressed in their nightshirts and petticoats. I want to find the little carved cherub and painted orange sunflowers that the pastor demanded from Paula and Clara by way of a penance.

Inside a group of women is decorating the church for a wedding. They look up as I come in, smile, and then turn back to their work. They are tying small bouquets onto the ends of the grey-painted pews; lilies, white roses and ivy. Aluminium buckets and vases half-filled with water stand among the aisles. All the women seem to know each other and chat while they work. The walls are whitewashed, as if the snow has blown in under the door and through the cracks, filling up the little church. The scent of lilies is overpowering. Cut stalks lie scattered on the stone floor in the zinc light. At one end of the knave is a simple carved altar, at the other an organ, its gleaming pipes graded like a set of shining steel teeth.

I wonder what it would be like to be a bride. What it would have been like if things had been different. And for a moment I can’t think of anything other than that last kiss on the crowded station, snatched amid the stream of embarking and disembarking passengers, the warmth of your mouth, your smell mingling with mine before you pulled away and walked out of my life forever. A slim figure in a long tweed coat and felt hat, carrying your violin.

I watched as long as I could, as you made your way past the kiosk with its hoarding for Manoli cigarettes, past the elderly businessman waiting on the corner in a black coat with an astrakhan collar, past the young soldiers and porters, watched as you walked towards the train that would take you back to your American wife; out of my arms forever, to safety across the sea. So many leavings and partings. Brothers, husbands, lovers, sons, and then the whistle, the high-pitched wail of the train, like a knife in my heart.

I return to that image over and over, rummaging in my brain like someone searching for an old photograph at the back of a drawer. But I’m afraid of spoiling it with overuse, so that it becomes as faded as an over-washed dress. Memories are all I have now. It was a risk to say goodbye, let alone snatch that last kiss. But how could I have asked you to stay? I imagine you, now, on that ship, halfway across the Atlantic, halfway across the world, dancing with your wife in her ivory chenille dress that shows off her thin white shoulders and slender neck with its string of milky pearls. I can see the band in the ballroom. Their white tuxedos and black bow ties, the trombonist’s cheeks puffed out like two balloons: I can’t give you anything but love, baby… and I remember that afternoon when I came for a lesson and you put that record on the phonograph, lowered the needle and took me in your arms, humming those words in my ear, as we danced round your study, watched by the plaster busts of Beethoven, Handel and Chopin.

I came here because I need to make sense of the past. My childhood was spent with my father Otto and with Louise who, to all intents and purposes, acted as my mother, and with Elsbeth and my young half-brothers, Ulrich and Christian. Then there were the years of music study in Munich. It was a well-regulated, ordered life. How hurt Father would be if he knew that I’d come to Worpswede. I think he’d feel betrayed, as though he hadn’t done enough. Of course he did his best, but what did he know about bringing up a small child? This place belongs to Paula and he never talked of her. That part of his life is a closed chapter. As far as the world’s concerned he’s Otto Modersohn, the famous artist. No one remembers her. No one remembers Paula Modersohn-Becker.

My parents married in May. It was a simple enough wedding. Paula in a white muslin dress, my father, Otto, ten years older and a widower looking, from the photograph I still have, stern and professorial in his dark suit, with his wire glasses and newly trimmed beard. Paula is much shorter; her hair looped simply at the nape of her neck. I’m told by those who knew her, by my Aunt Milly and my grandmother, that I look a little like her. It feels strange to think of these family events that preceded my birth. I try to imagine them, but I can’t. In the wedding picture my half-sister, Elsbeth, is holding a small nosegay. She looks very serious and seems to be embracing her role as handmaiden. She spent seven years with my mother. I only had days.

Was Paula happy on her wedding day? I think she must have loved my father then, or at least believed that she did. But how can I possibly know? Perhaps, in the end, all relationships are a compromise. Who knows why anyone else makes the decisions they make. Why the squat little man with a receding hairline is the focus of one woman’s passion, or what the blond boy sees in his older married lover? And I’ll never know for sure how much Paula really wanted me; really wanted a child or if, given the choice, she would have stayed on in Paris working in the thick of things and not have come back to Worpswede. In the end, despite me, Father, and even Rilke, painting was the most important thing in her life. I treasure these photographs and carry them everywhere. For me my mother will always be defined by the one taken by the photographer who came from Dresden days after I was born, where she stares dark-eyed directly into the camera from her bed, as I, Mathilde, lie in her arms testing out my week-old lungs.

The snow is falling faster now, scattering over the well-tended graves like a coating of icing sugar. As I walk through the church porch into the cemetery I hear a crunch on the gravel and look up to see an old man clearing the paths. He has a shaven, bullet-shaped head and wears a coarse potato-coloured jacket. He nods as I pass, then looks down again and goes back to sweeping the falling snow.

It’s very silent, as though the world is slowly being buried. Spruce and small fir trees line the paths. I’m not sure where my mother is as I search among the moss-covered tombstones carved with angels and fat-faced cherubs. Many of the headstones are inscribed in old Gothic script. I brush off the falling flakes with my bare hands, but still can’t decipher the inscriptions, and continue making my way up and down the rows, stopping at a pale upright slab and a simple rough-hewn granite stone. Then, as I turn a corner and walk down a path I’ve not walked before, I see it on the far side of the churchyard by the hedge.

How could I have missed it, the carving of a woman with bare breasts draped in Grecian robes, reclining on a mausoleum? A small child sits in her lap. I go up closer and see the woman isn’t touching the child, but is staring up at the dark sky. It’s Paula—my mother—with me, carved in white marble. The mason’s made me look older than I was when she actually died. It feels odd to be part of a memorial to the dead whilst I’m still alive. I don’t know who paid for it, but I doubt it was my father. I stand staring at the statue thinking about the cells dividing within me, cells half-made up of your DNA, and realise that whoever we are, whatever we’ve done, we’ll all end up in a place like this. Then I unwrap the white roses I brought from Bremen, and lay them in my stone mother’s arms. Soon the fragile petals are covered in snow.

Is that why I came? To fill the space left by you, Daniel, with the memory of her? I want to go back to that yellow house with the red roof where I spent my first weeks. For me it’ll always be more than just a house with a sloped attic, flowered wallpaper and a vase of freshly picked sweet peas on the sill. For me, it’ll always be home.

It’s getting very cold now. I try to retrace my footsteps to the gate, but they’ve disappeared beneath the falling snow. I have to find somewhere to stay before it gets really dark. Tonight, while I sleep in some strange bed, I’ll dream, as I always do, of you.

And tomorrow? Well, tomorrow, I shall begin my search for Paula.

PAULA

The elbe was clogged with ice and flood water streamed off the mountains. Torrents of rain alternated with flurries of snow, piling in drifts along the roads, hedgerows and railway lines. Though a conscientious man, Woldemar Becker couldn’t worry about his wife. He’d have to leave that to the midwife. The new railroad embankments along the river were giving way. Not only were millions of Deutschmarks at stake, but his reputation as an engineer. Men were battling up to their knees in the icy slush, shoring up the banks with wooden stakes and iron girders, trying to prevent collapse.

After the old nurse had cleared away the afterbirth, wrapped up the bloodied sheets, swaddled the baby and placed her in her mother’s arms she changed her stained apron, heated some coffee and overfilled the paraffin stove so the flames shot up in an inferno towards the velvet curtains. Screaming, she ran to the young mother’s bedside, where, despite her recent long labour, the young woman had the presence of mind to extinguish the blaze. What with the commotion, bad weather and the worry that her husband would be buried beneath an avalanche of snow and mud, Mathilde Becker developed an infected breast, which had to be wrapped in hot poultices and then lanced. Yet even though it took her six months to recover from her confinement, she didn’t love her third child less than any of her others.

Inside the freezing church the pastor held the lace bundle in the crook of his arm, dipped a big beetroot hand into the stone font and marked the child’s forehead, just beneath her frilled silk bonnet, with the sign of the cross. The icy water made her scream, but Woldemar Becker looked on indulgently, for he’d never been one of those men who only wanted sons.

‘Look, my dear,’ he said, turning to his wife, ‘at her snub nose. And those lungs! Our little daughter has quite an opinion already. See how she grips my finger and reaches for her old Papi’s beard.’

As Paula knelt on the Turkish rug among the swirls of dark acanthus leaves she could feel the scratchy wool even through her thick winter stockings. She had rushed through her sums and music practice and was laying out her pencils and sticks of charcoal next to a large sheet of paper on the floor. On the far side of the room was her mother’s bureau with the little drawers stuffed with letters tied in red ribbon, and the Venetian glass paperweight with green florets that went on and on forever when she held it up to the light. And by the door there was the mahogany cabinet of Dresden china that had belonged to her grandmother. The silver samovar her father had brought from Odessa, which sat next to the tawny owl in a glass case, that stared down at her with its beady yellow-glass eyes from its high shelf. Above the fireplace was the portrait of Mutti in a dove-grey dress, her long hair tied with a blue bow, painted before she married Papi. She must have been about eighteen. Only seven years older than Paula was now.

The coals in the grate glimmered making shadows in the room’s cold corners and, despite the heavy velvet curtains, there was still a draught. As Paula pulled the stick of charcoal over the paper, the carriage clock on the mantel ticked into the silence. Chiaroscuro; recently she’d learnt that this was the word for the effects of contrasted light and shade. The great artist, Leonardo, Papi had told her, when’d he got down the big leather book in his study to show her the engraved plates, had been the pioneer. Other artists such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt had also experimented with it. It was one of the great discoveries of the Renaissance and, if she wanted to be serious about her art, then she’d need to master this difference between light and dark.

Chia-ro-scuro: she rolled the Italian word round her mouth like a lump of barley sugar. Then, sitting back to admire her handiwork, wiped her fingers on her pinafore leaving black smears on the clean white cotton. Why weren’t the marks on the paper she made more like the thing she actually saw? She tried to make the charcoal lines look like the cat, but they remained flat and inert. With the ball of her thumb she smudged the edges to soften the contours but as she did so the cat got up, stretched and walked off with its tail in the air.

She laid her left hand on the paper and traced round the square nails and ragged cuticles that Mutti was always scolding her for biting. So what if the cat left? She didn’t care. She would be her own model. She got up and went to the mirror by the door and examined the tawny eyes and slightly bulbous lips reflected back at her. She wished that she had Mutti’s mouth. But that was just vanity. She had nice chestnut hair and rosy cheeks and should be satisfied with what God had given her. She may not be as pretty as her big sister Milly, but it wasn’t a bad face, at least one she could draw whenever she wanted.

Outside in the snow-filled streets she could hear the muffled shouts of the errand boys dropping off pumpernickel and pickled herrings to Frau Linderman, and the clatter of the iron rings on the beer kegs as they rolled over the cobbles into the cellars. It was even too cold for the dogs to bark. They’d slunk back into the warmth of their kennels.

Earlier that morning Paula had gone with Kurt and Milly to the park. The sky had been the colour of slate and the ground iron with frost. They had slid across the frozen lake, laughing and falling in heaps, bumping their knees and blowing on their raw hands. One or two of the other children had real skates with steel blades, but the Becker children just slid around in their button boots. Across the ice they could smell the chestnut-seller’s brazier. He’d been there every winter they could remember in his hat with ear flaps, his fingerless mittens and dirty charcoaled hands. Paula wondered where he came from with his strange accent and where he went in the summer. Some of the other children said he was from Silesia and that if you weren’t careful he’d steal you away like the Pied Piper and you’d never be seen again. Others swore he lived in a hut on the edge of a forest and was married to a witch. One day, as he was setting up his brazier, some boys threw stones at him and ran off shouting that he was a dirty Jew. Yet he always smiled at them showing his broken black teeth, and added an extra chestnut to their brown-paper twist.

On Sundays there was usually a puppet show in the park. There was also a zoological garden where, on warm days, the whole family would go to watch the Siberian tigers padding backwards and forwards behind the thick iron bars, and the monkeys with rude behinds rattling their cages, demanding peanuts. Further up the hill there was a museum and a castle filled with antiquities. It was there that Papi had shown her Raphael’s Madonna di San Sisto in its room with crimson fabric walls, and the Madonna by the younger Holbein, as well as Carreggio’s La Notte. But her favourite painting was of the English King, Charles I, with his Queen and their children, by Van Dyck. She wondered what it would have been like to meet them, these boys and girls dressed in their fine silks, who would have been the same age as her, and her brothers and sisters. She could have practised her English: the weather is a little inclement for the time of year; I live in the beautiful town of Dresden.

But her favourite spot was where the park was left to grow wild. On fine summer days they would take their skipping ropes and sketchbooks, their apples and flasks of milk and spend the afternoon lying amid the poppies and long grass, listening to the thrush in the willows. Across the lake she’d watch the families taking the air, the nannies in starched uniforms pushing their charges in big black perambulators.

Dresden was the only place that Paula had ever lived during her twelve years on earth. She knew nowhere other than this city with its cupolas and towers, spires and copper roofs, where the Altstadt, with its rococo churches, was separated by the slow running Elbe from the Neustadt, and connected by five bridges. How lucky she was, Papi insisted, to live in the German Florence. What better place to grow up for someone who wanted to be a painter.

Perhaps she should have guessed that something was up when, flushed from skating, Mutti had hurried them to wash their hands and get to the lunch table quickly. Their father had something to tell them. Papi didn’t usually join them for the midday meal. Normally he dined with the engineer and the accountant in the hotel next to the town hall where they ate sausage and sauerkraut, drank beer and sat in the dark smoking room with their cigars, talking of stocks and shares and the newly built sections of railway for which he was responsible. Rivets, sleepers and bolts, that’s what made a good railway. A line was only ever as good as the engineer who designed it and the builder who built it, he insisted, wreathed in clouds of smoke.

But today Papi was to eat lunch at home with his wife and children. First they said grace—though Paula knew he only bowed his head in deference to Mutti—before slicing the black bread and ladling out the pork and cabbage from the steaming tureen. Kurt was served first, then Milly and her. After that came Günther and the twins, Herma and Henner, for this was a household where the girls were given their rightful places in front of their younger brothers. As they ate her father spread his napkin on his lap and cleared his throat. Change, he announced, built character, and they were all about to experience a major change. They’d soon be moving to Bremen for he had recently been appointed Inspector for the Construction and Maintenance of the Berlin–Dresden Railway.

With his salt and pepper beard, mop of greying hair, and his navy blue jacket with the brass buttons, her Papi looked well-suited to this important new job, which was perfect for a man passionate about technology and the latest scientific developments. He followed, with a keen interest, the developments in electro technology and engineering being used to improve new factories along the Elbe, turning the old crafts of paper and soap-making into modern industries. He devoured the writings of Nietzsche and followed the debates of the Englishman Darwin, with his progressive ideas on the origin of the species. Darwin, much to Mutti’s sadness, was Papi’s hero; and, like Darwin, he had lost his faith in God. Sometimes her Papi could seem rather fierce. But Paula knew that was because he was often troubled. She was never sure why the world seemed to sit so heavily on his shoulders. Why a man who read so much, a kind man, should have such dark moods. She wished he was a believer and, every night before she went to bed, knelt and prayed that he would be returned to his faith. But, young as she was, she understood that he had a different map of the world.

She tried to be good and make him happy. She loved it when he crept up behind her when she was drawing, so she didn’t know that he was there until she felt his whiskers on her cheek and smelt the familiar tang of pomade and cigar smoke.

‘That’s very good, Paula. Well done. But look, the cat’s front leg’s too long. Can’t you see? You need to measure more carefully if you’re going to be a proper artist.’

Her Papi was a creature of habit. Most evenings he read in his study until well past midnight. Long after she should have been asleep she’d see the sliver of light from his desk lamp escaping under his shut door. In the morning he’d rise early before the rest of the house and weigh himself on a pair of scales in his dressing gown and socks, then mark the result on a little chart that he kept pinned to the wall. He always took breakfast alone in his room, except on Sundays: stewed apple, pumpernickel with cheese, and a glass of hot water with a slice of lemon. While he ate he read books on philosophy or the genetics of plant propagation, which he propped up against the honey jar. He never left his room unless properly dressed; his socks neatly held up with garters, and the correct dimple pressed into his cravat. The last thing he did was fold a clean handkerchief into four squares and tuck it into the pocket of his double-breasted jacket.

At a quarter to eight on the dot, after selecting his overcoat according to the weather, he left the house. He’d slip his arm into the right sleeve, then shake the chosen coat up onto his shoulder and insert the other arm, adjusting the hang of the cloth in front of the long hall mirror. When dressed to his liking he’d pick up his letters and newspaper; kiss any of his children that he happened to pass in the hall on the top of their heads, before taking a brisk walk to the office of the Inspectorate of the Dresden division of the Prussian railroads.

*

Woldemar Becker discussed everything with his wife, and this move to Bremen was no exception. Later that night, when the children were asleep, he listened for the rustle of her skirts as she made her way down the tessellated tile hall in the dim gas light to his study. He knew she’d take the change in her stride; that she had a rare gift which he did not, with his melancholy nature, of attracting people into her orbit. He’d been lucky in his choice of bride. Not only had she been beautiful—and still was in a solid mature sort of way with that lovely mouth of hers, even after seven children and the death of little Hans—but she exuded warmth.

And she had been a great comfort to him; for somehow he’d never quite got over the loss of the boy. He’d often wondered what it had been that had made him so special among his children. He always suspected it was because he’d been conceived on their wedding anniversary, when the apple tree was in bloom.

Hans had shared his interest in the natural world and loved to go down to the pond at the bottom of the garden to collect newts and frogs’ spawn. He’d take the boy by one hand, in the other carrying a net and jar, and sit for hours watching him fish in the green water. Then they would carry back the murky container and set up the brass microscope on the mahogany table, and he would explain how tadpoles grew legs and shed their tails to become frogs. Woldemar Becker believed in encouraging his children’s interests. Drawing in Paula, natural history in Hans, to whom he read about each stage of the amphibian life-cycle from the large encyclopedia. But these were things that he never spoke of now and kept shut away in his heart.

He knew that he’d not been much help to his wife in the days after the boy had been taken by scarlet fever. He had no words for the loss of the small son he had watched fading in the narrow bed, set up in quarantine in the little attic room away from the other children. Alone in his study, late at night, he could still see the child’s eyes shining in his flushed face. Yet despite the poultices, the hot flannels soaked in mustard, the enemas and bed baths, nothing had cooled the child’s fever. If Becker had ever doubted there was a God, he knew it for certain now. That was something he shared with the great Darwin; for he, too, had lost his beloved daughter and, with her death, his faith.

After the funeral, when his other children had stood in a forlorn huddle underneath the damp yews in coats stitched with black armbands, watching as the little white coffin was lowered into its grave, Woldemar Becker shut himself away in his study with his books and a hole in his heart.

It had been Mathilde who’d held the family together, despite her own grief; who had helped his children through their tears. In the dark, cold hours of morning, she’d held his head to her breast as he’d sobbed like a baby and reached for the comfort of her beneath her flannel nightgown. And it would be Mathilde who would ease their transition from Dresden to Bremen. It would only be a matter of time before she was calling on the neighbours, inviting them to evening soirées where she’d serve spiced wine and poppy-seed cake. His warm-hearted, congenial wife would soon have exchanged visiting cards with half the neighbourhood. And with this new job as administrator of the Prussian railroads for the city-state of Bremen came an official residence—a spacious house with a big garden that would provide plenty of room for the children to play.

No, it wasn’t altogether a bad thing this move to Bremen.

And Paula; what did she remember of Hans’ funeral? Above all she remembered the rain. How it had soaked into her coat with the velvet collar and run down her neck. That Hans was dead she knew. That her little brother was never coming back she understood, but standing there in the cemetery as the autumn leaves drifted among the graves, she couldn’t make any sense of it. How could he just not exist any more? Suddenly everything seemed so fragile and uncertain. All the things that had defined her childhood were changing. Her brother was gone and they were moving to another city.

After the funeral she went to her father’s study and lifted down the large atlas to look at the map of Bremen. Papi had explained it was one of the Hanseatic cities that occupied the sandy plain on the banks of the Weser and had one of the finest buildings in northern Germany. The fifteenth-century Rathaus—with its Renaissance facade studded with windows made up of hundreds of tiny leaded panes—dominated the market square. She wanted to see the famous statue of Roland—who was said to be very handsome—and explore the winding cobbled streets flanked by massive gabled houses. But Hans’ death had affected her badly. Bremen might be beautiful but it wasn’t her home. And she couldn’t bear the thought of leaving little Hans here, alone, in his newly dug grave with no one to visit him or lay flowers on his headstone.

*

She was to have the large room at the top of the house with the slanted gables and a window seat that looked out over the walnut tree. Her elder sister Milly had been given the bed furthest from the door, whilst she was to have the one in the alcove. This was a grown-up room, not a nursery. The walls were moss green and the curtains sprigged with Alpine flowers. In the corner was a washstand, a basin and a jug. The first thing Paula did was unpack her paintbrushes and crayons, which she lined up in old coffee tins on her desk beside her sketchbooks. When she’d organised everything to her liking she curled up on the window seat and sat staring out into the wet garden.

‘Milly, come here,’ she said, drawing her knees up under her pinafore and beckoning over her sister, who was arranging her undergarments in the chest of drawers. ‘Look, at the end of the garden, do you see, there’s a swing? Oh Milly, we’re going to have such fun. Come and sit by me. Tell me what you plan to be when you’re grown-up and your little sister is a famous painter?’

Maybe now that they’d left Dresden Paula would leave the nightmares behind. She couldn’t bear it any more. The dead-white face that appeared in the middle of the night, leaving her sweating with fear. She had loved her cousin, more than her own sisters, more even than little Hans. Only eighteen months older than Paula, they had been like twins. Cora had grown up in Indonesia and had only recently returned to Germany. With raven hair and a serious demeanour she had quickly become her younger cousin’s confidante and friend.

‘Oh, do tell me about your visit to the Buddhist temple, Cora. It sounds so exotic. Will you read me The Little Mermaid again while I draw you? Do you think you could ever do that, divide your tail into legs, even though it felt as if you were walking on a thousand knives? Can love really make you do such things? I’m not sure I could, even for a Prince. I want to be a painter.’

It had been a long hot summer afternoon. Six children had been playing in the park, flying kites and sailing wooden boats on the pond, pushing them out onto the sparkling water with sticks to catch the wind. In the heat they had taken off their shoes and stockings to build a castle in the sandpit near the linden trees, but the boys had become bored and started to scratch at the sand on all fours like dogs, sending it flying in all directions.

‘Look, we’re digging to the other side of the world. Come on Cora, come on Paula, get in. Now pat it down. Oh my God, quick, somebody, quick…’

She could still feel the weight of the sand pressing against her ribs, feel the grit in her nostrils and mouth, hear her brother’s frightened voice calling and calling in the distance, as the faint whimpering slowly faded to silence. Then they led her away from the crumpled heap splayed on the sand like a rag doll. She was told not to look back, yet deep inside she knew what had happened.

It had been no one’s fault, they told her. She shouldn’t blame herself. But why had her cousin been taken and not her? Why had she survived? Surely some day God would punish her. She lay on her bed for days, not eating and staring at the ceiling, as a fly buzzed inside the frosted-glass shade. Gradually it dawned on her that life was not what you deserved, but what was dished out to you and she was afraid. Afraid of the future, afraid that she’d never be able to make anything of herself and justify her survival, afraid that there wouldn’t be enough time to learn all she needed to know, that she didn’t have the talent or the grit to become an artist. Night after night Cora appeared to her, her dark hair floating about her white face, like someone drowning.

‘Oh please God, not tonight. If I’m good and not stubborn or egotistical please, please tell Cora that, though I love her very much, I’d be grateful if she stayed in Dresden.’

Nothing fancy. Some gingerbread, coffee and a little sweet wine. He’d have no vulgar display, no pretence that his family was anything that they weren’t, Papi insisted, as Mutti announced she would be giving a small house-warming party.

Paula and Milly were stirring flour through the big sieve, adding brown sugar, cinnamon and ginger into the white mixing basin as they discussed what they’d play for their guests. Mutti wanted Paula to play the Brahms but Milly preferred Schumann.

‘We could do both,’ Milly suggested, squashing the butter into the cake mix with the back of a wooden spoon. ‘But there’s not much time to practise, Paula, if you’re also going to paint the backdrop. The twins can play a duet. That always goes down well. Even when they make mistakes everyone thinks they’re sweet sitting side by side in their sailor suits.’

‘And Günther can do his card trick, and Kurt recite a poem,’ Paula added, pouring the mix into the floured tin. ‘Then Mutti can sing some Lieder. You know how much everyone enjoys that,’ she added, licking the last of the mixture off the spoon. ‘No one will notice if I don’t play.’

They weren’t rich, she knew, but Mutti loved beauty. The house was always filled with vases of flowers arranged in the Japanese style and small dishes of gourds and quince that her mother gathered from the garden. Mutti had even hung all the paintings in the house herself, going from room to room with her little hammer and picture pins. And everywhere there were books: new editions of the German classics, works by modern English and French writers. This evening’s gathering was to include Paula’s governess, Fräulein Lindesmann, and their neighbours the Schlegels and the Schäfers, as well as the local doctor. The day they’d arrived from Dresden he had knocked on the door and, with a low bow that had made Mutti blush, presented her with a bunch of violets. And today Paula was going to meet her new drawing tutor. She had begged Papi to let her have private lessons and finally he had relented, agreeing that if she was going to be an artist then she’d better take her studies seriously. He had made enquiries. A local painter by the name of Wiegandt seemed suitable. He had studied in Berlin and spent a month touring Italy, drawing the churches in Venice and Rome, and now made a fair living as a society portrait and landscape painter. What’s more, he was newly married and came from a respectable family.

‘Should I put clips in my hair, the little tortoise ones I got for Christmas, or tie it back with my brown ribbon? What do you think, Milly?’

But there was no time to fuss. She still had to lay the table with the best Swiss lace cloth and put out the silver coffee pot, the creamer and sugar bowl with the little tongs. Everything had to be perfect. At last she was going to study art, not just sit at the table in the morning room on rainy afternoons drawing the cat or Kurt slumped in his chair.

After Milly played the Schumann, Paula handed round the refreshments. Despite Papi’s insistence on simplicity, they had baked a large cheesecake, which her mother was slicing onto the best Dresden plates. She took a piece over to Fräulein Lindesmann seated on the ottoman. When she grew up she wanted to be like her teacher and have a plaid dress with a silver brooch at the throat. She loved the way Fräulein Lindesmann wound her blonde hair around her head in a thick halo of plaits. She was far too lovely, the beautiful, the divine Fräulein Lindesmann, to be a governess for long. Surely some handsome man would come along and whisk her away and marry her. But Paula had to pluck up courage to offer a plate of cake to Frau Schlegel with her bosom like a shelf in brown bombazine, and grains of face powder that quivered in the dark hairs on her upper lip.

The Golden Section, Herr Wiegandt explained the following afternoon, was a portion in which a straight line or a rectangle was divided into two equal parts so that the ratio of the smaller to the greater was the same as that of the greater to the whole. Perhaps, he asked, adjusting the buttons on his velvet waistcoat with his long white fingers that reminded her of early asparagus, she’d come across the value of pi in her study of geometry?

Paula shook her head. She’d no idea that learning to draw would be so complicated.