5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

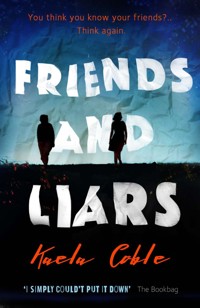

It has been ten years since Ruby left her hometown behind. Since then she's built a life away from her recovering alcoholic mother and her first love, Murphy. But when Danny, one of her estranged friends from childhood, commits suicide, guilt draws Ruby back into the tumultuous world she escaped all those years ago. She's dreading the funeral - and with good reason. Danny has left a series of envelopes addressed to his former friends. Inside each envelope is a secret about every person in the group. Ruby's secret is so explosive, she will fight tooth-and-nail to keep it hidden from those she once loved so deeply, even if that means risking everything...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

FRIENDS AND LIARS

Kaela Coble is a member of the League of Vermont Writers, a voracious reader, and a hopeless addict of bad television and chocolate. She lives with her husband in Burlington, Vermont, and is a devoted mother to their rescued chuggle, Gus. Friends and Liars is her first novel.

FRIENDSANDLIARS

KAELA COBLE

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2017 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Kaela Coble, 2017

The moral right of Kaela Coble to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 205 0E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 206 7

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To my crew, for the family kind of friendship that endures through all the drama, that feels the same no matter the time or distance between meetings, and that loves even when it doesn’t like.

PROLOGUE

DANNY

Now

Look at them. I’m dead and they’re still pissing me off.

They’re disgusting. Sitting in their pew, huddled together like a pack of wolves. Each playing their part in mourning—the bereaved, the wilted, the guilty. They clutch at each other, leaning physically and emotionally for support. Shaking heads, balled fists, crocodile tears. Asking why, how. Dabbing their swollen eyes with crumpled tissues. Declaring their loyalty and love for one another. For me.

Really they hate each other, and they hate themselves, and they hate me for making them face their own mortality. And they love me because it fuels their sick sense of pride in their little clan. “The crew,” they call themselves, even though they haven’t been whole for a decade. “Still supporting each other after all these years,” they declare, even though they wouldn’t know true support if it helped them climb out of a grave.

There’s Ally, the great beauty of Chatwick, sitting tall and stoic, practically cradling Steph in her arms. She shoots glances at her husband, Aaron. High-school sweethearts; couldn’t you just puke? Her face is a marriage of self-righteousness and pride. Steph is a girlfriend of the crew, not an original member. What right does she have to this display? But no matter what, and despite their resistance, Ally is their leader. She is the mother of the crew, the default person in whom to find solace.

Emmett and Aaron sit together instead of with their respective significant others, no doubt upon Emmett’s insistence. He has always orchestrated the seating arrangements to split between genders. As the youngest of three brothers, he has always been uncomfortable with the noise, the gossip, and the full range of feminine feelings. The heightened emotional state caused by my death is no doubt more unbearable for him than my death itself. That he is allowing Ally to tend to his weeping girlfriend, offering no comfort of his own, comes as no surprise.

He and Aaron mimic the same posture—leaned forward, their elbows resting on the thighs of their cheap woolen pants. They face the front of the church, careful not to make eye contact with each other, so they won’t have to utter one of the lame platitudes they’ve heard too many times over the past few days. “He’s in a better place.” “He’s finally at peace.” And my personal favorite, “Roger is watching over him now.”

While they should be focusing on the tragedy that is (was) my life, instead my casket is a big fat polished-cedar reminder that one day this will be them. They ponder all the predictable questions that even people of the mildest intellect contemplate when faced with untimely death: Where do we go when we die? What will they say about me when I’m gone? What does it all mean? Tomorrow they will look into low-premium life insurance plans to take care of their burgeoning families should something happen to them. It will make them feel like men in control of their lives. But they’re not. They’re boys, and they’re not in control of shit.

Speaking of boys, Murphy isn’t here, the coward. He always picks the easiest option, and in this case (and many cases), that means hiding. I’m dead, lying here about to be carried off and buried, but all he cares about is winning the argument. Murphy showing up would mean I got the last word, or that he had forgiven me, and either of those would mean he’s weak. He doesn’t realize he’s the weakest one of the bunch anyway.

That brings me to Ruby. She sits in the pew between the girls and the boys, the space between her and them so slight you would only notice if you were looking for it, like I am. She watches Ally comforting Steph, occasionally reaching out a hand to squeeze one of Ally’s. I know Ruby feels genuine grief, but mostly discomfort. She doesn’t know her place anymore, her role. I’m only now realizing that she never really knew it. She’s been an official outsider ever since she dared leave Chatwick at eighteen, but even before that, she and I were always the ones straddling the curvature of the crew’s closed circle. One foot in, one foot out. The dark ones.

I know it’s terrible how much enjoyment I get from watching her squirm, but it’s just too entertaining. Besides, with the fate of my soul no longer a question mark, I’m enjoying what I can. My death will be hardest on Ruby, for sure, but she’ll never admit it, and our crew won’t acknowledge it. She left. She abandoned us, so she can’t possibly feel it as deeply as they do. It’s amazing how grief turns so quickly from a group activity to a competitive sport.

It seems all of Chatwick turned up in their patent-leather shoes and cheap polyester blends. “To show their support,” they say. For who? Me? I don’t even know half these people. Four days ago they wouldn’t have pissed on me if I was on fire. Most of them are only here to satisfy their morbid curiosity, whispering behind hands and rolling eyes, gathering tidbits to relay later to their neighbors who were unable to make it. But some are here for my mother, Charlene, whose deli (formerly my stepfather’s) is where they happily depleted their food-stamps. Either way, I wish they wouldn’t have come. It makes them feel too damn good about themselves, and they don’t deserve it. And I don’t deserve the show, either, even if it is fake.

Mom stares blankly ahead of her as the priest eulogizes yet another man who’s let her down. I look—well, looked—just like her. If you shaved off her two curtains of waist-length blonde curls and straightened out her chest and hips, we would look like twins.

Nancy, Ruby’s mother, sits next to Mom, holding her limp hand. Nancy is the one who made all these arrangements, and despite the overabundance of flowers, I still appreciate her efforts. She saved my mother from having to coordinate another funeral, and I think one is enough for a lifetime. Ruby’s never forgiven her mother for the way she handled her illness back in the day, but as dicey as things got in the St. James household, they didn’t hold a candle to my family. Besides, Nancy’s one of the only assholes in this town who has any compassion, and I’m grateful she’s decided to bestow it upon Mom when she needs it most.

That’s all I ever needed. Compassion. If I’d ever gotten a shred of it from any of the people in this room, maybe I wouldn’t be in this fucking box.

My “friends” all think once they’ve fulfilled this obligation they will finally be rid of me. They will go back to the “happy,” normal, vanilla lives they lead, and their guilt will subside eventually.

Silly rabbits. They have no idea my mom found the letters this morning.

CHAPTER ONE

RUBY

Now

I’m the first to arrive at Charlene’s house, so I opt for street parking in case I need to make a hasty escape. I’ve never much cared for being caged in. Especially not in Chatwick.

Staring at the house, the last place my friend Danny was alive, I remember when he moved in here the summer after his stepfather died. Charlene used the moderate payout from Roger’s life-insurance policy to buy it, and with what was left over she fixed up the apartment over the deli where the three of them lived so she could rent it out. She and her son needed a fresh start, she explained to neighbors who raised their eyebrows at the sudden move, so soon after Roger’s death. Her first (and only) house project was to coat it with the hideous teal paint that remains today, enlisting the crew to do the bulk of the work. She paid us in subs that she brought over every day after the lunchtime rush. At the end of the day she served us iced tea she mixed in a large glass pitcher as we melted onto the front porch steps and teased each other about who smelled the worst after a hard day’s labor. I can practically smell the iced tea, the paint fumes, and the sweat. It had been a happy time, mostly, but not as innocent as it should have been. At least for those of us who already knew that nothing was as it seemed.

The paint is now chipped and faded, but it still glows with the spark of Charlene’s quiet defiance. She never said as much, but she had chosen it as a message: she no longer had to answer to anyone. She no longer had to rely on anyone else to keep her and her son alive. Her choices were hers and hers alone, and if she wanted a teal house, then by God she would have one.

My hands are wrapped so tightly around the steering wheel my palms begin to sweat. I consider driving away, straight out of Chatwick to Drummond, where the plane I am supposed to be blissfully seated on is currently being prepared for its flight back to JFK. In just over ninety minutes, I could be out of Vermont and back to my apartment in Manhattan, with the blinds shut. But I see Charlene’s pleading eyes in my mind, asking me to please come to the private service Danny requested. There would be no public reception where my absence would hardly be noticed; it was just the crew. That’s what Danny had wanted. I wondered briefly how she could possibly know what Danny had wanted, before it sank in. He had left a note. Up until that moment, none of us knew if the overdose was an accident or suicide, and no one knew which was worse. Now we know; this is worse, of course. Much worse. Charlene watched the realization dawn in my eyes before confirming it. “There’s letters for all of you,” she said.

Damnit. I wouldn’t even be here if it weren’t for Ally. I was the first person she called when she heard the news. My initial instinct was to not take the call, but when someone you haven’t spoken to in ten years tracks you down at work at eleven o’clock in the morning, you take the call. If it had been anyone other than Ally, I would have had the receptionist take a message. Then I would have sent a nice card to Charlene (because Danny hated flowers), and I would have returned to pretending that nothing beyond the borders of Manhattan ever existed. It was Ally’s voice, the shock and the pain and the . . . Allyness of it. The way she hadn’t asked but demanded my return. “I’ve never asked you why, Ruby, and I still won’t. But you’ll come for the funeral. You have to.” What she meant, without saying it directly, was that I owe her. And I do. For leaving and never looking back. For leaving her behind and never telling her why.

If only I hadn’t picked up the phone, I would be at my desk in New York, feeling guilty but safe. Not plagued by the ceaseless nerves bubbling under my skin. Not overcome by an urge to smoke that I haven’t had in ten years. There are so many things in Chatwick that aren’t good for me, and if I go in that house, I’ll be sucked back into them all. I’ll spin right back down the drain of this town.

Just as I make up my mind to get the hell out of here before anyone else arrives, Charlene swings open the screen door and stands on the porch with one hand on her hip, the other over her eyes, so she can see who’s lingering outside her house like a private detective. She recognizes me and waves. Shit! You can’t drive away from a grieving mother.

The door of the Sentra squeaks as I swing it open. I took a cab from the airport this morning because Nancy was busy helping Charlene get ready for the funeral, but since I had an hour between my arrival and the funeral, I went . . . home, I guess, is its rightful name. I no longer had a key to the house, but the code to the garage hasn’t changed (my sister Coral’s birthday, followed by my own). In addition to the spare key that hangs behind my old ice skates, I found, to my surprise, Blue, my high-school car, still a piece of junk with its four-gear standard transmission, power nothing, and heat that runs full blast all year long whether you want it to or not. My father purchased it second-hand for me the year he moved back in with us, a consolation prize for his absence. Despite my insistence I wouldn’t need it after I left for college, Nancy has kept it here for me. The key was sitting in the ignition, and instead of going into the house I was not ready to face, I sat in the car and listened to a cassette tape—a cassette tape!—of songs I had recorded from the radio when I was sixteen years old.

I climb the rotting steps to Charlene, who stands on her tiptoes to hug me. I am not tall, five-foot-seven in my tallest pair of heels, which I left at home—my real home, that is, in New York—but Charlene is a teeny size two; the top of her head barely clears my shoulders. I feel like a beast descending on her.

“Oh, Ruby,” she says, her hands on my face, her puffy eyes beseeching mine. “Thanks for comin’. It’s so good to see you.” She looks me all over and declares me as beautiful as ever. “Now, come have some iced tea with your long-lost mother-in-law.” She includes this self-assigned title in the Christmas cards she sends every year, despite the fact that I haven’t spoken to her son in ten years. She always hoped Danny and I would fall in love, as if I had the power to set his life on the right course. Now more than ever, perhaps unintentionally, it serves as a reminder that I could have saved her son.

As if reading my mind, she stops in her path to look at me warily. “I guess I should stop doing that,” she says. “Pushin’. You know, now that there’s nothin’ to push.”

I don’t know what to say, so I just shake my head with a sad smile and follow her into the kitchen. Charlene deposits me on one of the red leather and chrome chairs she tells me she picked up at the Margie’s Pub remodeling sale for five bucks a pop. I thought they looked familiar, although technically I shouldn’t know what they look like. She pulls out the same pitcher from her fridge that she served us from fifteen summers ago and pours it into a glass I distinctly remember Danny serving us vodka-and-orange sodas in a few years later. She offers me vegetables from a platter that she next produces from the fridge, and I wonder how she’s still standing, let alone serving me like I’m on a social call and her son will be home to join us any minute.

In keeping with this charade, Charlene insists I tell her about my “life in the big city.” There isn’t much to tell, so I talk about work. On the plane, I contemplated telling people who asked that I work at The New York Times and leaving it at that, letting them assume I’ve been away from Vermont for so long because I was busy achieving the ambition I listed in my high-school yearbook: to be a journalist. But now, at my first opportunity, I hasten to add that it’s in the advertising department, because I don’t want Charlene to think I’m putting on airs. Who was I kidding? For one, I’m sure she and my mother have talked about me and my career at least once since I’ve been gone. And even if by some miracle Nancy has let me fade into the sordid history of this town, it is Chatwick. Despite the fact that I don’t have a Facebook page, I bet you could walk out on this street and ask anyone what Ruby St. James is up to, and they would reply: “Oh, the St. James girl? Reddish hair? Oh yes, she’s living in New York, working at that big paper of theirs. I hear she’s single, as always, and pays more in rent than this whole neighborhood spends on mortgage combined!”

My friends and I always called it “the Chat,” this rapid-fire circulation of the unprinted news of Chatwick. The Chat is an intangible presence which cloaks the town in intrigue and fear. The houses are so close together here that every argument even one notch above normal speaking level is overheard by the little old ladies rocking the afternoon away on their screened-in porches. Their gossip filters down through whispered conversations at post-church-service receptions, then the parents repeat it at home it in earshot of their kids, who bring it to the playground. The other (and significantly more powerful) origin is Margie’s Pub, which trickles news down to the Quik Stop clientele the next day, which brings it back to the “below the tracks” families, or the blockers. Subjects run the gamut from legal troubles to marital stress, right on down to who’s dating who at Chatwick High. No one is immune. I remember Ally once having to defend herself against a neighbor who heard that Ally had broken up with her friend’s grandson over the phone. We were in fifth grade.

Danny’s family and mine were like gas pumps, fueling the Chat for years on end. From our home, the neighbors would occasionally hear Nancy crashing around the house trying to get from room to room, and shortly afterward a shouting match between my parents. At the Deusos’ they heard much worse.

The doorbell rings, and Charlene escorts Ally and Aaron in. Ally carries a freshly baked pie, and the gap in time between now and the last time I saw her feels wide as a canyon. Her face—voted Prettiest in junior high and high school—is the face of the girl I stole my mother’s car with before I even had a license, driving it all over town, smoking cigarettes. It’s the face of the girl who told the crew what sex was, her giddy face lit by flashlight in the field behind her house, using the same hand motions she had seen her brother use when he explained it to his friend earlier that day. In that same field, years later, she would gather us together—me, Emmett, Danny, and Murphy, the original crew—to tell us her father had left. After a summer of her parents arguing over the rubbers her mom had found in her dad’s pockets while doing the laundry, this came as a shock to no one but Ally, whose fierce belief in true love left her unprepared. That was the night she made us promise to be friends always. To be loyal to one another above all else. Never to lie to each other. She needed something to cling to, and I could understand that, so I promised, like Ally promised and Emmett promised. Like Danny and Murphy promised, even though the three of us were already breaking it. Even though we’ve done nothing but break it since that night.

And now, Ally’s a grown woman. From the clippings my mother periodically sends me from The Chatwick Gazette, I know she’s recently been promoted to manager at The Cutting Edge, the salon where she’s worked since she graduated from cosmetology school. I picture her ruling the roost from her position behind her chair, affectionately clucking directions to her junior hairdressers without taking her eyes off the clump of hair she’s expertly snipping away at. Gathering bits of gossip from her clients like bits of feed. As we listened to the memorialization of our friend, I noticed Ally scanning my hair, and I know she was contemplating whether she would give me highlights or lowlights. She won’t get the opportunity. I don’t care how much practice she’s had, I remember all too well the time in eighth grade when she convinced me to darken my hair to a chocolatey-brown. She dyed it out of a box we got at Brooks’ Pharmacy. I cried for a week until the black streaks came out.

Since we’ve last seen each other, she’s married the man beside her, the man we all knew she would marry since the moment he rescued her from a scum-of-the-earth date at Dunphy’s field after homecoming. And I’ve become the girl who didn’t even attend their wedding. Ally’s become a person I don’t know. Someone who knows that it’s expected to bring food to a bereaved person. I imagine this knowledge was passed down to her in some kind of handbook that women receive on their wedding day, which tells you how to handle every uncomfortable situation that life presents.

Next in the door are Emmett and Steph, Emmett looking impossibly mature in a suit and tie that he moves in as comfortably as if he wears it every day. I get a flash of our eighth-grade formal dance, me straightening his tie for him every ten minutes. He was so obsessed with keeping it straight, but so uncomfortable in it that he couldn’t stop tugging at it, ruining my efforts. He blamed me for tying it wrong, so I told him to screw off, which started the common splitting of alliances between the girls and the boys of the crew. Oh, the drama of those days, over a tie and a few harsh words. Over absolutely nothing at all. How I long for that now.

Nancy tells me Emmett works in finance now, in the loans department. Apparently he golfs with my father on Sundays. The WASPiness of it all turns my stomach. I half expected him to walk in with a cable-knit sweater tied around his shoulders. There is something different about the way Emmett moves now, and it takes me a minute to pinpoint it. He used to bound into a room, filling every molecule of air with nervous energy, constantly in motion. Now he moves slowly, cautiously, and only his eyes dart around the room anxiously. I attribute it to the situation; it must be difficult to attend the funeral of the boy you once treated like a fly to be swatted.

Steph, whom Ally had pointedly introduced to me at the funeral as Emmett’s girlfriend of three years, (in case I didn’t already understand how ludicrous it was that I hadn’t even known she existed), is tiny in comparison to Emmett but just as smartly dressed. She has warm brown eyes, and when I hugged her at the service I felt an instant comfort with her. Perhaps this is because, comparatively, our embrace wasn’t impregnated with ten years of absence, resentment, and disappointment. She carries a fruit basket, thus debunking my wedding day Uncomfortable Situation Handbook theory. I am feeling more and more inadequate with each guest.

Everyone takes turns hugging, even though we already went through this at the church and then again before leaving the cemetery. But it’s something to do, I guess. When the ritual is over, there is nothing else to do but to shift uncomfortably until Charlene tells us the reason we’ve all been summoned here, and why we were the only ones invited.

“Must be weird for you to be back here,” Emmett says, his talent for adding more tension to a room already humid with it still, unfortunately, intact. I feel my face instantly begin to burn as I search for an appropriate response. Am I to apologize for being gone so long? I know that’s what they’re all expecting. At the very least, it’s what they deserve.

“At least she is here,” Ally cuts in. “More than I can say for Murphy.”

Even as it softens to Ally’s defense of me, my heart jumps at the name. After all the anxiety at the thought of seeing him, Murphy wasn’t at the funeral. When Charlene told us about the closed reception, she had asked me where Murphy was, as if no time had passed and I was still the keeper of his whereabouts. Ally had jumped in and offered to make sure he came. I had overheard her on her cell phone before I closed the door to my car: “Murphy Leblanc, if you don’t put aside your stupid pride and get your ass over to Charlene’s house—” In that moment, despite my leftover resentment, I felt sorry for him. He and I were in the same boat, helpless against Ally’s authority, even if we were rowing in opposite directions.

We hear a vehicle pull up in the driveway, but when minutes pass without a knock on the door, Ally goes over to the window and peers through the curtains. “Speak of the devil,” she says. My stomach drops. He’s here. Like a ghost conjured by speaking its name, what I’ve been simultaneously dreading and looking forward to since I returned to Chatwick is now parked not fifty feet from where I stand, separated only by a rotting porch and a bright teal wall.

I can’t help but join Ally at the window. There Murphy is, sitting in a truck I’ve never seen before. The side is emblazoned with the logo for Leblanc Johnson Construction, the contracting company Nancy tells me he has owned with Aaron for some time. His arms are stretched out straight, with the same death grip on his steering wheel as I had moments earlier. “What’s he doing?” I ask.

Ally rolls her eyes and snaps her tongue. “Who knows? Aaron, can you go see if he’s coming in for a landing anytime soon?”

“What am I supposed to say?” Aaron asks, a deer caught in headlights. Business partner or no, he wants as little as possible to do with the emotional turmoil that today is bringing up. He’s a dude. A proper one.

Everyone is quiet. I lock eyes with Emmett, silently battling to relinquish this task to the other. I surrender more easily than I should. “I’ll go.” I head through the door before there can be any more discussion. The first time Murphy and I see each other should be just the two of us anyway, even if Ally has her nose pressed up against the windowpane the whole time.

I step out onto the porch, my breath catching in my throat as our eyes meet. I feel the pull. I’m circling the drain. Even though his window is rolled down, I can’t hear the four-letter word his mouth forms as he breaks eye contact, but it puts an abrupt halt to the centrifugal force anyway. Thank God.

“That happy to see me, huh?” I ask as I approach the driver’s side. Up close, I see that Murphy’s jet-black hair is now peppered with grey that’s too mature for his twenty-eight years, and his rolled-up shirtsleeve reveals a tattoo encircling his forearm, which is thicker, tanner, and more muscular than I remember. Otherwise, he looks exactly the same.

He exhales an unsmiling laugh but doesn’t make eye contact again. “Didn’t think I’d see you here.” His voice makes it more real. The voice I talked to every night on the phone until one of us fell asleep.

“Ally didn’t tell you I was coming home for the funeral?” Funny, Ally tells everyone everything, especially if she has a part in making it happen.

He ignores me. “Kinda forgot you even existed,” he says, staring straight ahead.

Even though I know he can’t possibly mean it, hearing the words and the icy tone of his voice feels like a bullet to the chest. A bullet I quite possibly deserve, although perhaps not fired by him.

“Why weren’t you there?” My voice falters, and I realize I had wanted him to be there more than I had wanted him not to be there. In fact, I had needed him to be there. Suddenly I wish he would jerk his head in the direction of the passenger side, indicating that he wants me to get in. To ride around the back roads of Chatwick, head down to the bay. As dirty as this section of town is, the below-the-tracks section where Danny grew up, if you stick with the road for another mile, suddenly it breaks open to beautiful green rolling pastures of farmland. I can smell the cow manure from here; it’s a sweeter smell than I remember. Past the farmland is Chatwick Bay, where we used to escape on the boiling hot summer nights—skipping rocks, talking about life, skinny-dipping. I suddenly ache to be sitting in Murphy’s passenger seat, my legs stretched out, my toes cold in the wind, headed away from the center of town and into our own little world.

Murphy still stares straight ahead, so I risk putting my hand on his arm. “Hey. Look at me.”

When he finally does, I see the anger and hurt burning in his eyes. I wonder if he can see the same in mine. “You’re not the only one I haven’t seen in a while,” he says, breaking our gaze almost immediately.

“You fought?” I ask, knowing the answer is yes before he nods, but not wanting him to know I know. It works in my favor that they stopped being friends just two weeks before Danny and I did. If they had continued to be as close as brothers, Murphy and I would be having a very different conversation right now. “What was it about?” And this I have truly never known, have tried not to want to know.

His face finally twists into a smile, although not the warm, easy one I remember. “It wasn’t about you, if that’s what you’re thinking.”

My mouth drops open in feigned shock, because that’s exactly what I was thinking. “That’s not what I was thinking!”

He snorts out an infuriating laugh.

“Excuse me for trying to figure out what could make the best of friends completely cut off communication for ten—” I stop, realizing what I’m saying. I am a huge pile of hypocritical crap.

Murphy doesn’t say anything, he simply continues to smile that scary, un-Murphy-like smile.

I raise my hands against the gun I imagine he’s about to reload. “Okay. You’re right, I’m no master communicator myself. It’s just ... I know what happened between the two of us,” and I wave my finger between him and myself. “And I know what happened between me and Danny. What I don’t know is what happened between the two of you.”

“Ruby, not everything is some dramatic thing. I told you it wasn’t about you. So mind your own damn business!” he says.

I spin to go back inside, anger and hurt stinging my eyes. I hear him curse and then the door of his truck opening and closing. He grabs at my elbow and I shrug him off, turning back to face him with my arms crossed.

“Tuesday!”

The nickname stops me in my tracks. Only he and Danny call me that. Now, I guess, it’s only Murphy. It used to drive me crazy, the way they would walk behind me in the halls in elementary school, singing that song over and over again until I shouted at them to stop. Now, I would give anything to hear Danny sing just one horribly out-of-tune chorus of “Goodbye, Ruby Tuesday.”

“Listen, I’m sorry,” Murphy says. “I’m a little shook up. It was a long time ago and neither of us got over it . . . in time. I don’t want to talk about it, because it seems stupid now. Everything seems kinda stupid.”

I know this is as much as I’m going to get from him. “Well, I tell you what’s stupid: us standing out here fighting while everyone else is inside, ready to hear what Danny has to say for himself. No one is looking forward to it, Murphy, but maybe . . . it will . . . help.” When the tears come to my eyes, I see, finally, graciously, his face soften. He takes a step forward, opening his arms to hug me, and I get a whiff of his cologne, the same stuff he’s always worn. I step backward, away from him, shaking my head. I can’t be hugged by Murphy. It will kill me; I’m sure of it. When I turn to climb the steps, I feel him hesitating behind me, but eventually he follows.

Charlene makes even more of a fuss over Murphy than she did over me. He looks sheepish, undoubtedly feeling the full weight of the rift between him and Danny, now that he’s in Charlene’s house with Danny’s school pictures lining the walls. Neither Murphy nor I will resolve our final fight with Danny, and both of us should have been fighting to keep him with us.

Charlene leads us into the basement, which is different from the last time I saw it. There’s a futon, a bed, and a mini-fridge. Danny must have adapted this room into an apartment of sorts, giving him the illusion of independence and the privacy to numb himself against the world. The hairs on the back of my neck stand up, and suddenly I know: Danny died in this room. I picture Charlene coming down with a basket of laundry, calling out in forced cheeriness, “Get up, lazybones!” only to find . . . I shudder. I can’t even go there. God help me from ever going there.

Aaron hands out the folding chairs we used to use for poker nights. He offers Charlene a chair, but she shakes her head. She stands in front of the old television we once screened porn on; the girls curious to see what all the fuss was about, the boys simply horny teenage boys. We arrange ourselves in a semicircle to face her, reluctant pupils in a class we never elected to take. The couples sit together, holding hands, while Murphy and I are lumped together off to the side. As always, the single ones.

I close my eyes, just for a second, and picture the crew as it used to be. Aaron and Ally remain unchanged, save for the wedding bands on their fingers, but suddenly it’s Emmett’s high-school girlfriend, Tara, by his side instead of Steph. Danny is in the corner, making out with whatever blocker he’s found to entertain him this month. And I—without anyone thinking anything of it—am able to lean into Murphy for support. In this world, at the end of the night it’s quite possible I’ll return home to find Nancy either high or low, or one of those plus drunk, but it still feels lighter and simpler than the reality I return to when I open my eyes.

Charlene holds a stack of envelopes and two sheets of loose-leaf paper. I can see Danny’s scribble through the white-lined sheet, and I remember the first time I looked over Danny’s shoulder at this same handwriting. He was showing me a poem he had written, which was better than I expected, much better than my own drippy attempts anyway. Charlene reads:

“Dear Mom,

I’m sorry I have to leave you this way. With all we have been through together, I always hoped I could someday make you proud. But life is hard, and sad. It has been for a very long time. At first, pot made it better, and then it didn’t, so I moved on to other things. They all helped at first, but then they didn’t anymore. And now I’m nothing but a junkie.”

Charlene’s voice falters here, and it takes her several minutes to get through the rest of the letter:

“I’m a disappointment as a son and as a human being. Nothing I do now can change that. I hate myself for what I’ve done. For what I am. I don’t even deserve the grief I know you must be feeling. Please don’t hate me. Try to be happy I’m finally at peace. I want you to know there is nothing you could have done to prevent this. You tried to help me as best you could.”

I can tell when she breaks down at this part that, no matter what Danny says, Charlene will always wonder what she should have done differently. As will we all.

“The trouble is, if a person has no hope things can get better, there’s not a whole lot anyone else can say to change that.

I love you very much,

Danny

P.S. There’s another letter I’d like you to read to Ruby, Murphy, Emmett, and Ally, if you can get them all together. Please read it before you give them their envelopes, or else they won’t understand.”

I barely hear the last part, I’m so furious with Danny. I’m sorry I have to leave you this way. As if he had no say in the matter. I could kill him, if he hadn’t already done such a thorough job of it.

“Got the autopsy results back yesterday,” Charlene whispers. “It was heroin. But I wasn’t sure if it was on purpose or not, until . . .” She flaps the piece of paper. “I found it when I finally made myself strip his bed this morning.” My eyes dart over to the bed, which I had been avoiding until this moment. The little twin mattress is made up with sheets so crisp and tightly tucked in, even Nancy at her most manic would approve. Then I remember Nancy telling me she was helping Charlene out with the arrangements, and realize this was probably her handiwork.

Heroin. Suicide. The weight of the words hangs in the air, already dense with emotion. Ally’s hand springs to her mouth, and Aaron wraps his arm around her. Murphy leans forward and hides his face in his hands. My hand shoots out instinctively to rub his back, freezing about an inch above his shirt when I realize the intimacy of what I’m about to do. I pat him awkwardly a few times and then return the disobedient hand to my lap. I look over at Emmett. Steph is looking at him too, but he stares straight ahead, white as a sheet. No one knows what to say. I mean, what do you say?

Finally Emmett seems to return to himself. He clears his throat. “The note says there’s letters for us?” I shoot him a sharp look. He’s trying to get this over with, and I understand the urge but don’t think rushing Charlene is very kind. He doesn’t notice my glare.

“Yeah,” she says. She puts the first sheet behind the second. “I haven’t read this one yet, since it ain’t addressed to me.” Even with her bastard ex-husband and her troubled son in the ground, Charlene is still waiting for someone’s temper to explode. She sniffs deeply and reads:

“To my old friends,

So here you all are. Nice to see you can show up for a person once he’s dead.”

Charlene stops, her mouth open, her eyes horrified at the abrupt change in tone. Her expression almost exactly matches those of Ally, Aaron, Emmett, and Steph. My face and Murphy’s have not changed; he and I were expecting this. Probably because we know we deserve it. Charlene’s eyes scan the rest of the page, and then she looks at me, as if she’s asking permission to continue. I nod my head to grant it.

She looks down at the page again, her hands shaking visibly. She looks back up at me and shakes her head. The first note was bad enough. She doesn’t want the last memory of her son to be this. I stand up, grab the box of tissues from the top of the TV, and guide her back to my seat with them. Murphy takes one of her hands. With the other, she dabs at her eyes with a tissue. I take Charlene’s place at the head of the class and continue reading:

“I haven’t heard from any of you in a while. Some of you I see down at Margie’s Pub every weekend, so I don’t know what makes you think you’re so much better than me. I doubt Ruby and Murphy are even here. They’re both really good at ignoring problems.”

I look at Murphy, who glances at me and then returns to staring straight ahead.

“If any of you actually showed up at my funeral, don’t feel like you deserve some medal. None of you bothered to try to help me when I was alive, when it counted.”

Ally is crying audibly now, her head in her hands, slumped into Aaron’s chest. Charlene’s eyes dart between each of our faces guiltily, as if she were the one who wrote the hateful words. “I’m sorry,” she says to us. “I didn’t know. I thought it would be like mine, not . . .” She waves her hand at the letter in mine. “Maybe we shouldn’t—”

But something in me tells me that Danny’s last words deserve to be read. Maybe the part of me that feels I contributed to his demise by abandoning him all those years ago. I turn my eyes back to the page and continue:

“You always talked about ‘the crew, the crew, the crew,’ like we were some untouchable entity. But when it comes to things that really matter, you guys barely even know each other. I think it’s about time you did, if you’re going to continue to pride yourselves on being friends since the womb. I know things about most of you that you didn’t trust the rest of ‘the crew’ to know.”

Here I pause, a hot spring of acid appearing in my throat. But I know if I choose not to continue reading, someone else will snatch this piece of paper away from me. If I read it, I can control the information if it reveals too much.

“There is one envelope for each of my dear friends who once pledged always to be honest with each other, and each envelope contains evidence of your betrayal of that pact. I’ll leave it up to you. You can either share the envelopes with each other, or keep them to yourselves. Just remember that all things done in the dark have a way of coming to light. If you don’t tell each other your secrets, you never know how, or when, I might have arranged for them to come out.”

He didn’t sign the letter “Love, Danny,” which is no surprise after the content. He simply dashed off a large, loopy “D.” I’m not sure what to do with the piece of paper. I don’t want to give it back to Charlene, so I place it on top of the television, next to the pile of envelopes, which I pick up. Each has a name on it. There is one for me, one for Ally, one for Emmett, one for Murphy, and one, oddly enough, for Danny himself. I hold them in my hands, little grenades of paper. If I tear them up now, will it stop them from detonating? Judging by the ferocity of Danny’s letter, I’m guessing not.

I hand out the envelopes, and as I do so each person looks at me, searching for answers to the questions on all of our minds. I drop the envelope with my name on it back on the TV set, left now only with Danny’s envelope in my hands, which says, “I’ll go first.” I know what it will say, and I wish I could somehow shrink down and disappear inside the envelope so I don’t have to deal with any of what’s about to happen. But I don’t debate with myself if I should open it or not, or if I should give it to Charlene for her to sort out instead. I just rip open the seal and pull out a small piece of paper. It says what I thought it might say.

I read aloud the truth that changed everything for Danny:

“I killed my stepfather.”

CHAPTER TWO

RUBY

Back then

I’m used to waking up in the middle of the night. Danny throws rocks at my window every couple of weeks. So tonight, when I bolt upright in bed, I wait to hear the next pebble before I bother getting up. I hold my breath, waiting for the ping! against the glass to slice through the thick summer air, but I don’t hear it. I draw the curtain to look out to the street, but no one’s there.

I lie down and try to fall back to sleep. Sometimes my ceiling fan, tired from the effort of keeping my room cool in the humidity of the Vermont summer, starts to creak in the middle of the night, and in the past I’ve mistaken the noise for Danny’s SOS. But my fan hasn’t been on since the storm knocked out the power hours ago. My phone call with Ally cut off mid-sentence after a flash of light, which I’m sure made her more worried. The first night I had a sleepover at her house—we were maybe five or six—there was a thunderstorm so big I couldn’t help but tell her I was scared, and she stayed up with me all night playing Go Fish, giving my hand a squeeze with every boom of thunder. Ever since then, she calls me to make sure I’m okay when it storms. Even though I’m over the fear, I love that she still checks on me.