7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

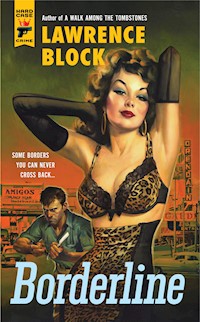

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

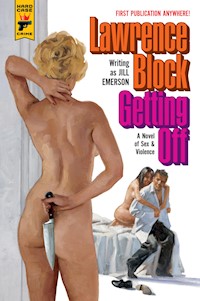

SO THIS GIRL WALKS INTO A BAR... ...and when she walks out there's a man with her. She goes to bed with him, and she likes that part. Then she kills him, and she likes that even better. On her way out, she cleans out his wallet. She keeps moving, and has a new name for each change of address. She's been doing this for a while, and she's good at it. And then a chance remark gets her thinking of the men who got away, the lucky ones who survived a night with her. She starts writing down names. And now she's a girl with a mission. Picking up their trails. Hunting them down. Crossing them off her list...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

BY LAWRENCE BLOCK

WRITING AS JILL EMERSON

WARM AND WILLING

ENOUGH OF SORROW

THIRTY

THREESOME

A MADWOMAN’S DIARY

THE TROUBLE WITH EDEN

A WEEK AS ANDREA BENSTOCK

GETTING OFF

OTHER HARD CASE CRIME NOVELS

BY LAWRENCE BLOCK

A DIET OF TREACLE

THE GIRL WITH THE LONG GREEN HEART

GRIFTER’S GAME

KILLING CASTRO

LUCKY AT CARDS

Getting OFF

A NOVEL OF SEX AND VIOLENCE

by Lawrence Block

WRITING AS JILL EMERSON

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-101)

First Hard Case Crime edition: September 2011

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

If you purchased this book without a cover, you should know that it is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

Copyright © 2011 by Lawrence Block. Portions of Getting Off appeared in somewhat different form in the anthologies Manhattan Noir, edited by Lawrence Block; Bronx Noir, edited by S. J. Rozan; Indian Country Noir, edited by Sarah Cortez & Liz Martinez; and Warriors, edited by George R. R. Martin and Gardner Dozois.

Cover painting copyright © 2011 by Gregory Manchess.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-0-85768-287-1

E-book ISBN 978-0-85768-599-5

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Printed in the United States of America

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

for CHARLES ARDAI

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

ONE

Pronouns suited her.

She, her, herself. These worked just fine. Names came and went, you were out the door and on a plane or a train or a bus, and your name stayed behind, along with whatever else you didn’t need anymore.

Once, in a man’s apartment, a book caught her eye. The title was She, by H. Rider Haggard, and she plucked it from the shelf and opened it at random. She read this passage:

Oh, how beautiful she looked there in the flame! No angel out of heaven could have worn a greater loveliness. Even now my heart faints before the recollection of it, as naked in the naked fire she stood and smiled at our awed faces, and I would give half my remaining time upon this earth thus to see her once again.

She might have read more, but she had to get out of there. The book’s owner was in the bedroom, as naked as the woman in the story, sprawled on his back with his sightless eyes staring at the ceiling. So she couldn’t stick around, and she wasn’t interested enough in the book to take it away with her. She’d take money, that was different, but she wouldn’t take a book, and she wiped her fingerprints from this one and returned it to its spot on the shelf.

When she was born her parents named her Katherine Anne Tolliver, and she grew up with seemingly endless variations of Katherine. Kathy, Katie, Kath, Kate.

Cat.

Kitty.

For a time, her father called her Kitten. The world shortened that to Kit, and somehow it stuck, and so he called her that as well.

Kit. Kit Tolliver.

The trouble with that, though, was that one name ran into the other, with her first name ending with the same letter that started her last name. So that someone hearing her name might think her surname was Oliver.

She still had the name when she graduated from high school. It was on her diploma, but some idiot misspelled it, left the E off her middle name. Katherine Ann Tolliver, it read, and that bothered her for about fifteen seconds. Then she realized she wouldn’t be keeping the diploma. Or the name, either.

All the same, she packed the diploma and took it with her when she moved to the Cities. She went first to a motel in Red Cloud, just to be out of Hawley, and nine days later she signed Katherine Tolliver to the lease of an apartment in St. Paul. It was a perfectly fine apartment, and she had a two-year lease, but she was gone after ten weeks. Done with the Cities, done with Minnesota altogether. Done with being Kit Tolliver.

There were plenty of other places to go, and when one was used up she never had trouble finding another. There were plenty of names, too, an endless supply of names, and she’d keep one for an hour or an evening or a week or a month.

And then get another one.

Once she took a man’s name along with his cash.

He’d given it as Les. “Les is more,” he’d told her, and laughed heartily, and it had been clear she was not the first woman to receive this assurance. And, when this particular Les was no more, she went through his wallet and discovered that his name was not Lester, as she’d more or less assumed, but Leslie. Leslie Paul Hammond was the name on his driver’s license, but on his credit cards the middle name was conveniently reduced to an initial.

Well, why not? The sexual ambiguity of the name made it easy enough, so why not let his AmEx card pay for a plane ticket, why not use his Visa to pay for a nice hotel room? It would be a while before anybody found him, and by then she’d have doubled back on her own trail, so anyone looking for her would be looking in the wrong places.

By then she’d be somewhere else. And by then she’d be somebody else.

Nothing to it.

She, by H. Rider Haggard.

She might have looked for a copy later on, but she never did. Instead she forgot about it, even as she forgot about the dead man in the other room. And all the men, and all the other rooms.

And moved on.

TWO

She felt his eyes on her just about the time the bartender placed a Beck’s coaster on the bar and set her dry Rob Roy on top of it. She wanted to turn and see who was eyeing her, but remained as she was, trying to analyze just what it was she felt. She couldn’t pin it down physically, couldn’t detect a specific prickling of the nerves in the back of her neck. She simply knew she was being watched, and that the watcher was a male.

It was, to be sure, a familiar sensation. Men had always looked at her. Since adolescence, since her body had begun the transformation from girl to woman? No, longer than that. Even in childhood, some men had looked at her, gazing with admiration and, often, with something beyond admiration.

In Hawley, Minnesota, thirty miles east of the North Dakota line, they’d looked at her like that. The glances followed her to Red Cloud and St. Paul, and other places after that, and now she was in New York, and, no surprise, men still looked at her.

She lifted her glass, sipped, and a male voice said, “Excuse me, but is that a Rob Roy?”

He was standing to her left, a tall man, slender, well turned out in a navy blazer and gray trousers. His shirt was a button-down, his tie diagonally striped. His face, attractive but not handsome, was youthful at first glance, but she could see he’d lived some lines into it. And his dark hair was lightly infiltrated with gray.

“A dry Rob Roy,” she said. “Why?”

“In a world where everyone orders Cosmopolitans,” he said, “there’s something very pleasingly old-fashioned about a girl who drinks a Rob Roy. A woman, I should say.”

She lowered her eyes to see what he was drinking.

“I haven’t ordered yet,” he said. “Just got here. I’d have one of those, but old habits die hard.” And, when the barman moved in front of him, he ordered Jameson on the rocks. “Irish whiskey,” he told her. “Of course this neighborhood used to be mostly Irish. And tough. It was a pretty dangerous place a few years ago. A young woman like yourself wouldn’t feel comfortable walking into a bar unaccompanied, not in this part of town. Even accompanied, it was no place for a lady.”

“I guess it’s changed a lot,” she said.

“It’s even changed its name,” he said. His drink arrived, and he picked up his glass and held it to the light, admiring the amber color. “They call it Clinton now. That’s for DeWitt Clinton, not Bill. DeWitt was the governor a while back, he dug the Erie Canal. Not personally, but he got it done. And there was George Clinton, he was the governor, too, for seven terms starting before the adoption of the Constitution. And then he had a term as vice president. But all that was before your time.”

“By a few years,” she allowed.

“It was even before mine,” he said. “But I grew up here, just a few blocks from here, and I can tell you nobody called it Clinton then. You probably know what they called it.”

“Hell’s Kitchen,” she said. “They still call it that, when they’re not calling it Clinton.”

“Well, it’s more colorful. It was the real estate interests who plumped for Clinton, because they figured nobody would want to move to something called Hell’s Kitchen. And that may have been true then, when people remembered what a bad neighborhood this was, but now it’s spruced up and gentrified and yuppified to within an inch of its life, and the old name gives it a little added cachet. A touch of gangster chic, if you know what I mean.”

“If you can’t stand the heat—”

“Stay out of the Kitchen,” he supplied. “When I was growing up here, the Westies pretty much ran the place. They weren’t terribly efficient, like the Italian mob, but they were colorful and bloodthirsty enough to make up for it. There was a man two doors down the street from me who disappeared, and they never did find the body. Except one of his hands turned up in somebody’s freezer on Fifty-third Street and Eleventh Avenue. They wanted to be able to put his fingerprints on things long after he was dead and gone.”

“Would that work?”

“With luck,” he said, “we’ll never know. The Westies are mostly gone now, and the tenement apartments they lived in are all tarted up, with stockbrokers and lawyers renting them now. Which are you?”

“Me?”

“A stockbroker? Or a lawyer?”

She grinned. “Neither one, I’m afraid. I’m an actress.”

“Even better.”

“Which means I take a class twice a week,” she said, “and run around to open casting calls and auditions.”

“And wait tables?”

“I did some of that in the Cities. I suppose I’ll have to do it again here, when I start to run out of money.”

“The Cities?”

“The Twin Cities. Minneapolis and St. Paul.”

“That’s where you’re from?”

They talked about where she was from, and along the way he told her his name was Jim. She was Jennifer, she told him. He related another story about the neighborhood—he was really a pretty good storyteller—and by then her Rob Roy was gone and so was his Jameson. “Let me get us another round,” he said, “and then why don’t we take our drinks to a table? We’ll be more comfortable, and it’ll be quieter.”

He was talking about the neighborhood.

“Irish, of course,” he said, “but that was only part of it. You had blocks that were pretty much solid Italian, and there were Poles and other Eastern Europeans. A lot of French, too, working at the restaurants in the theater district. You had everything, really. The UN’s across town on the East River, but you had your own General Assembly here in the Kitchen. Fifty-seventh Street was a dividing line; north of that was San Juan Hill, and you had a lot of blacks living there. It was an interesting place to grow up, if you got to grow up, but no sweet young thing from Minnesota would want to move here.”

She raised her eyebrows at sweet young thing, and he grinned at her. Then his eyes turned serious and he said, “I have a confession to make.”

“Oh?”

“I followed you in here.”

“You mean you noticed me even before I ordered a Rob Roy?”

“I saw you on the street. And for a moment I thought—”

“What?”

“Well, that you were on the street.”

“I guess I was, if that’s where you saw me. I don’t...oh, you thought—”

“That you were a working girl. I wasn’t going to mention this, and I don’t want you to take it the wrong way—”

What, she wondered, was the right way?

“—because it’s not as though you looked the part, or were dressed like the girls you see out there. See, the neighborhood may be tarted up, but that doesn’t mean the tarts have disappeared.”

“I’ve noticed.”

“It was more the way you were walking,” he went on. “Not swinging your hips, not your walk per se, but a feeling I got that you weren’t in a hurry to get anywhere, or even all that sure where you were going.”

“I was thinking about stopping for a drink,” she said, “and not sure if I wanted to, or if I should go straight home.”

“That would fit.”

“And I’ve never been in here before, and wondered if it was decent.”

“Well, it’s decent enough now. A few years ago it wouldn’t have been. And even now, a woman alone—”

“I see.” She sipped her drink. “So you thought I might be a hooker,” she said, “and that’s what brought you in here. Well, I hate to disappoint you—”

“What brought me in here,” he said, “was the thought that you might be, and the hope that you weren’t.”

“I’m not.”

“I know.”

“I’m an actress.”

“And a good one, I’ll bet.”

“I guess time will tell.”

“It generally does,” he said. “Can I get you another one of those?”

She shook her head. “Oh, I don’t think so,” she said. “I was only going to come in for one drink, and I wasn’t even sure I wanted to do that. And I’ve had two, and that’s really plenty.”

“Are you sure?”

“I’m afraid so. It’s not just the alcohol, it’s the time. I have to get home.”

“I’ll walk you.”

“Oh, that’s not necessary.”

“Yes, it is. Whether it’s Hell’s Kitchen or Clinton, it’s still necessary.”

“Well...”

“I insist. It’s safer around here than it used to be, but it’s a long way from Minnesota. And I suppose you get some unsavory characters in Minnesota, as far as that goes.”

“Well, you’re right about that,” she said. And at the door she said, “I just don’t want you to think you have to walk me home because I’m a lady.”

“I’m not walking you home because you’re a lady,” he said. “I’m walking you home because I’m a gentleman.”

The walk to her door was interesting. He had stories to tell about half the buildings they passed. There’d been a murder in this one, a notorious drunk in the next. For all that some of the stories were unsettling, she felt completely secure walking at his side.

At her door he said, “Any chance I could come up for a cup of coffee?”

“I wish,” she said.

“I see.”

“I’ve got this roommate,” she said. “It’s impossible, it really is.

My idea of success isn’t starring on Broadway, it’s making enough money to have a place of my own. There’s just no privacy when she’s home, and the damn girl is always home.”

“That’s a shame.”

She drew a breath. “Jim? Do you have a roommate?”

*

He didn’t, and if he had the place would still have been large enough to afford privacy. A large living room, a big bedroom, a good-sized kitchen. Rent-controlled, he told her, or he could never have afforded it. He showed her all through the apartment before he took her in his arms and kissed her.

“Maybe,” she said, when the embrace ended, “maybe we should have one more drink after all.”

She was dreaming, something confused and confusing, and then her eyes snapped open. For a moment she did not know where she was, and then she realized she was in New York, and realized the dream had been a recollection or reinvention of her childhood in Hawley.

In New York, and in Jim’s apartment.

And in his bed. She turned, saw him lying motionless beside her, and slipped out from under the covers, moving with instinctive caution. She walked quietly out of the bedroom, found the bathroom. She used the toilet, peeked behind the shower curtain. The tub was surprisingly clean for a bachelor’s apartment, and looked inviting. She didn’t feel soiled, not exactly that, but something close. Stale, she decided. Stale, and very much in need of freshening.

She ran the shower, adjusted the temperature, stepped under the spray.

She hadn’t intended to stay over, had fallen asleep in spite of her intentions. Rohypnol, she thought. Roofies, the date-rape drug. Puts you to sleep, or the closest thing to it, and leaves you with no memory of what happened to you.

Maybe that was it. Maybe she’d gotten a contact high.

She stepped out of the tub, toweled herself dry, and returned to the bedroom for her clothes. He hadn’t moved in her absence and lay on his back beneath the covers.

She got dressed, checked herself in the mirror, found her purse, put on lipstick but no makeup, and was satisfied with the results. Then, after another reflexive glance at the bed, she began searching the apartment.

His wallet, in the gray slacks he’d tossed over the back of a chair, held almost three hundred dollars in cash. She took that but left the credit cards and everything else. She found just over a thousand dollars in his sock drawer, and took it, but left the mayonnaise jar full of loose change. She checked the refrigerator, and the set of brushed aluminum containers on the kitchen counter, but the fridge held nothing but food and drink, and one container held tea bags while the other two were empty.

That was probably it, she decided. She could search more thoroughly, but she’d only be wasting her time.

And she really ought to get out of here.

But first she had to go back to the bedroom. Had to stand at the side of the bed and look down at him. Jim, he’d called himself. James John O’Rourke, according to the cards in his wallet. Forty-seven years old. Old enough to be her father, in point of fact, although the man in Hawley who’d sired her was his senior by eight or nine years.

He hadn’t moved.

Rohypnol, she thought. The love pill.

“Maybe,” she had said, “we should have one more drink after all.”

I’ll have what you’re having, she’d told him, and it was child’s play to add the drug to her own drink, then switch glasses with him. Her only concern after that had been that he might pass out before he got his clothes off, but no, they kissed and petted and found their way to his bed, and got out of their clothes and into each other’s arms, and it was all very nice, actually, until he yawned and his muscles went slack and he lay limp in her arms.

She arranged him on him on his back and watched him sleep. Then she touched and stroked him, eliciting a response without waking the sleeping giant. Rohypnol, the wonder drug, facilitating date rape for either sex. She took him in her mouth, she mounted him, she rode him. Her orgasm was intense, and it was hers alone. He didn’t share it, and when she dismounted his penis softened and lay upon his thigh.

In Hawley her father took to coming into her room at night. “Kitten? Are you sleeping?” If she answered, he’d kiss her on the forehead and tell her to go back to sleep.

Then half an hour later he’d come back. If she was asleep, if she didn’t hear him call her name, he’d slip into the bed with her. And touch her, and kiss her, and not on her forehead this time.

She would wake up when this happened, but somehow knew to feign sleep. And he would do what he did.

Before long she pretended to be asleep whenever he came into the room. She’d hear him ask if she was asleep, and she’d lie there silent and still, and he’d come into her bed. She liked it, she didn’t like it. She loved him, she hated him.

Eventually they dropped the pretense. Eventually he taught her how to touch him, and how to use her mouth on him. Eventually, eventually, there was very little they didn’t do.

It took some work, but she got Jim hard again, and this time she made him come. He moaned audibly at the very end, then subsided into deep sleep almost immediately. She was exhausted, she felt as if she’d taken a drug herself, but she forced herself to go to the bathroom and look for some Listerine. She couldn’t find any, and wound up gargling with a mouthful of his Irish whiskey.

She stopped in the kitchen, then returned to the bedroom. And, when she’d done what she needed to do, she decided it wouldn’t hurt to lie down beside him and close her eyes. Just for a minute...

And now it was morning, and time for her to get out of there. She stood looking down at him, and for an instant she seemed to see his chest rise and fall with his slow even breathing, but that was just her mind playing a trick, because his chest was in fact quite motionless, and he wasn’t breathing at all. His breathing had stopped forever when she slid the kitchen knife between two of his ribs and into his heart.

He’d died without a sound. La petite mort, the French called orgasm. The little death. Well, the little death had drawn a moan from him, but the real thing turned out to be soundless. His breathing stopped, and never resumed.

She laid a hand on his upper arm, and the coolness of his flesh struck her as a sign that he was at peace now. She thought, almost wistfully, how very serene he had become.

In a sense, there’d been no need to kill the man. She could have robbed him just as effectively while he slept, and the drug would ensure that he wouldn’t wake up before she was out the door. She’d used the knife in response to an inner need, and the need had in fact been an urgent one; satisfying it had shuttled her right off to sleep.

Back in Hawley, her mother’s kitchen had held every kind of knife you could imagine. A dozen of them jutted out of a butcherblock knife holder, and others filled a shallow drawer. Sometimes she’d look at the knives, and think about them, and the things you could do with them. Cutting, piercing. Knife-type things.

“You’re my little soldier,” her father used to say, and she felt like a soldier the night of her high school graduation, marching when her name was called, standing at attention to receive her diploma. She could feel the buzz in the audience, men and women telling each other how brave she was. The poor child, with all she’d been through.

She never touched her mother’s knives, and for all she knew they were still in the kitchen in Hawley. But a few weeks later she left her apartment in St. Paul and went bar-hopping across the river in Minneapolis, and the young man she went home with had a set of knives in a butcher-block holder, just like her mother’s.

Bad luck for him.

She let herself out of the apartment, drew the door shut and made sure it locked behind her. The building was a walk-up, four apartments to the floor, and she made her way down three flights and out the door without encountering anyone.

Time to think about moving.

Not that she’d established a pattern. The man last week, in the posh loft near the Javits Center, had smothered to death. He’d been huge, and built like a wrestler, but the drug rendered him helpless, and all she’d had to do was hold the pillow over his face. He didn’t come close enough to consciousness to struggle. And the man before that, the advertising executive, had shown her why he’d feel safe in any neighborhood, gentrification or no. He kept a loaded handgun in the drawer of the bedside table, and if any burglar was unlucky enough to drop into his place, well—

When she was through with him, she’d retrieved the gun, wrapped his hand around it, put the barrel in his mouth, and squeezed off a shot. They could call it a suicide, even as they could call the wrestler a heart attack, if they didn’t look too closely. Or they could call all three of them murders without ever suspecting they were all the work of the same person.

Still, it wouldn’t hurt her to move. Find another place to live before people started to notice her on the streets and in the bars. She liked it here, in Clinton or Hell’s Kitchen, whatever you wanted to call it. It was a nice place to live, whatever it may have been in years past. But, as she and Jim had agreed, the whole of Manhattan was a nice place to live. There weren’t any bad neighborhoods left, not really.

Wherever she went, she was pretty sure she’d feel safe.

THREE

She woke up abruptly—click! Like that, no warmup, no transition, no ascent into consciousness out of a dream. She was just all at once awake, brain in gear, all of her senses operating but sight. Her eyes were closed, and she let them remain that way for a moment while she picked up what information her other senses could provide.

She felt the cotton sheet under her, smooth. A good hand, a high thread count. Her host, then, wasn’t a pauper, and had the good taste to equip himself with decent bed linen. She didn’t feel a top sheet, felt only the air on her bare skin. Cool, dry air, air-conditioned air.

Whisper-quiet, too. Probably central air-conditioning, because she couldn’t hear it. She couldn’t hear much, really. A certain amount of city noise, through windows that were no doubt shut to let the central air do its work. But less of it than she’d have heard in her own Manhattan apartment.

And the energy level here was more muted than you would encounter in Manhattan. Hard to say what sense provided this information, and she supposed it was probably some combination of them all, some unconscious synthesis of taste and touch and smell and hearing, that let you know you were in one of the outer boroughs.

Memory filled in the rest. She’d taken the 1 train clear to the end of the line, following Broadway up into the Bronx, and she’d gone to a couple of bars in Riverdale, both of them nice preppy places where the bartenders didn’t look puzzled when you ordered a Dog’s Breakfast or a Sunday Best. And then...

Well, that’s where it got a little fuzzy.

She still had taste and smell to consult. Taste, well, the taste in her mouth was the taste of morning, and all it did was make her want to brush her teeth. Smell was more complicated. There would have been more to smell without air conditioning, more to smell if the humidity were higher, but nevertheless there was a good deal of information available. She noted perspiration, male and female, and sex smells.

He was right there, she realized. In the bed beside her. If she reached out a hand she could touch him.

For a moment, though, she let her hand stay where it was, resting on her hip. Eyes still closed, she tried to bring his image into focus, even as she tried to embrace her memory of the later portion of the evening. She didn’t know where she was, not really. She’d managed to figure out that she was in a relatively new apartment building, and she figured it was probably in Riverdale. But she couldn’t be sure of that. He might have had a car, and he might have brought her almost anywhere. Westchester County, say.

Bits and pieces of memory hovered at the edge of thought. Shreds of small talk, but how could she know what was from last night and what was bubbling up from past evenings? Sense impressions: a male voice, a male touch on her upper arm.

She’d recognize him if she opened her eyes. She couldn’t picture him, not quite, but she’d know him when her eyes had a chance to refresh her memory.

Not yet.

She reached out a hand, touched him.

She had just registered the warmth of his skin when he spoke.

“Sleeping beauty,” he said.

Her eyes snapped open, wide open, and her pulse raced.

“Easy,” he said. “My God, you’re terrified, aren’t you? Don’t be. Everything’s all right.”

He was lying on his side facing her. And yes, she recognized him. Dark hair, arresting blue eyes under arched brows, a full-lipped mouth, a strong jawline. His nose had been broken once and imperfectly reset, and that saved him from being male-model handsome.

Early thirties, maybe eight or ten years her senior. A good body. A little chest hair, but not too much. Broad shoulders. A stomach flat enough to show a six-pack of abs.

No wonder she’d left the bar with him.

And she remembered leaving the bar. They’d walked, so she was probably in Riverdale. Unless they’d walked to his car. Could she remember any more?

“You don’t remember, do you?”

Reading her mind. And how was she supposed to answer that one?

She tried for an ironic smile. “I’m a little fuzzy,” she said.

“I’m not surprised.”

“Oh?”

“You were hitting the Cosmos pretty good. I had the feeling, you know, that you might be in a blackout.”

“Really? What did I do?”

“Nothing they’d throw you in jail for.”

“Well, that’s a relief.”

“You didn’t stagger or slur your words, and you were able to form complete sentences. Grammatical ones, too.”

“The nuns would be proud of me.”

“I’m sure they would. Except...”

“Except they wouldn’t like to see me waking up in a strange bed.”

“I’m not sure how liberal they’re getting these days,” he said. “That wasn’t what I was going to say.”

“Oh.”

“You didn’t know where you were, did you? When you opened your eyes.”

“Not right away.”

“Do you know now?”

“Well, sure,” she said. “I’m here. With you.”

“Do you know where ‘here’ is? Or who I am?”

Should she make something up? Or would the truth be easier?

“I don’t remember getting in a car,” she said, “and I do remember walking, so my guess is we’re in Riverdale.”

“But it’s a guess.”

“Well, couldn’t we call it an educated guess? Or at least an informed one?”

“Either way,” he said, “it’s right. We walked here, and we’re in Riverdale.”

“So I got that one right. But why wouldn’t the nuns be proud of me?”

“Forget the nuns, okay?”

“They’re forgotten.”

“Look, I don’t want to get preachy. And it’s none of my business. But if you’re drinking enough to leave big gaps in your memory, well, how do you know who you’re going home with?”

Whom, she thought. The nuns wouldn’t be proud of you, buster.

She said, “It worked out all right, didn’t it? I mean, you’re an okay guy. So I guess my judgment was in good enough shape when we hooked up.”

“Or you were lucky.”

“Nothing wrong with getting lucky.”

She grinned as she spoke the line, but he remained serious. “There are a lot of guys out there,” he said, “who aren’t okay. Predators, nut cases, bad guys. If you’d gone home with one of those—”

“But I didn’t.”

“How do you know?”

“How do I know? Well, here we are, both of us, and...what do you mean, how do I know?”

“Do you remember my name?”

“I’d probably recognize it if I heard it.”

“Suppose I say three names, and you pick the one that’s mine.”

“What do I get if I’m right?”

“What do you want?”

“A shower.”

This time he grinned. “It’s a deal. Three names? Hmmm. Peter. Harley. Joel.”

“Look into my eyes,” she said, “and say them again. Slowly.”

“What are you, a polygraph? Peter. Harley. Joel.”

“You’re Joel.”

“I’m Peter.”

“Hey, I was close.”

“Two more tries,” he said, “and you’d have had it for sure. You told me your name was Jennifer.”

“Well, I got that one right.”

“And you told me to call you Jen.”

“And did you?’

“Did I what?”

“Call me Jen.”

“Of course. I can take direction.”

“Are you an actor?”

“As sure as my name is Joel. Why would you...oh, because I said I could take direction? Actually I had my schoolboy ambitions, but by the time I got out of college I smartened up. I work on Wall Street.”

“All the way downtown. What time is it?”

“A little after ten.”

“Don’t you have to be at your desk by nine?”

“Not on Saturday.”

“Oh, right. Uh, Peter...or do I call you Pete?”

“Either one.”

“Awkward question coming up. Did we...”

“We did,” he said, “and it was memorable for one of us.”

“Oh.”

“I felt a little funny about it, because I had the feeling you weren’t entirely present. But your body was really into it, no matter where your mind was, and, well—”

“We had a good time?”

“A very good time. And, just so that you don’t have to worry, we took precautions.”

“That’s good to know.”

“And then you, uh, passed out.”

“I did?”

“It was a little scary. You just went out like a light. For a minute I thought, I don’t know—”

“That I was dead,” she supplied.

“But you were breathing, so I ruled that out.”

“That keen analytical mind must serve you well on Wall Street.”

“I tried to wake you,” he said, “but you were gone. So I let you sleep. And then I fell asleep myself, and, well, here we are.”

“Naked and unashamed.” She yawned, stretched. “Look,” she said, “I’m going to treat myself to a shower, even if I didn’t win the right in the Name That Stud contest. Don’t go away, okay?”

The bathroom had a window, and one look showed that she was on a high floor, with a river view. She showered, and washed her hair with his shampoo. Then she borrowed his toothbrush and brushed her teeth diligently, and gargled with a little mouthwash.

When she emerged from the bathroom, wrapped in his big yellow towel, the aroma of fresh coffee led her into the kitchen, where he’d just finished filling two cups. He was wearing a white terry robe with a nautical motif, dark blue anchors embroidered on the pockets. His soft leather slippers were wine-colored.

Gifts, she thought. Men didn’t buy those things for themselves, did they?

“I made coffee,” he said.

“So I see.”

“There’s cream and sugar, if you take it.”

“Just black is fine.” She picked up her cup, breathed in the steam that rose from it. “I might live,” she announced. “Do you sail?”

“Sail?”

“The robe. Anchors aweigh and all that.”

“Oh. I suppose I could, because I don’t get seasick or anything. But no, I don’t sail. I have another robe, if you’d be more comfortable.”

“With anchors? Actually I’m comfortable enough like this.”

“Okay.”

“But if I wanted to be even more comfortable...” She let the towel drop to the floor, noted with satisfaction the way his eyes widened. “How about you? Wouldn’t you be more comfortable if you got rid of that sailor suit?”

*

Afterward she propped herself up on an elbow and looked down at him. “I feel much much better now,” she announced.

“The perfect hangover cure?”

“No, the shower and the coffee took care of the hangover. This let me feel better about myself. I mean, the idea of hooking up and not remembering it...”

“You’ll remember this, you figure?”

“You bet. What about you, Peter? Will you remember?”

“Till my dying day.”

“I’d better get dressed and head on home.”

“And I can probably use a shower,” he said. “Unless you want to—”

“You go ahead. I’ll have another cup of coffee while you’re in there.”

Her clothes were on the chair, and she dressed quickly, then picked up her purse and checked its contents. She opened the little plastic vial, and counted the little blue pills.

Six of them, which was the same number she’d had at the start of the evening. Six little Roofies, so she hadn’t slipped one into his drink, as she’d planned.

Nor had she fucked up big time and taken Rohypnol herself, which was what she’d begun to suspect. Because she hadn’t been hitting the Cosmos anywhere near hard enough to account for the way the evening had turned out. It would have added up if she’d dosed his drink and then chosen the wrong glass, but she still had all her pills left.

Unless...

Oh, Peter, she thought. Peter Peter, pussy eater, what a naughty young man you turned out to be.

She returned the vial of blue pills to her purse and drew out the small glassine envelope instead. It was unopened, and held perhaps half a teaspoonful of a crystalline white substance. Not so fast as Rohypnol, according to her information, but rather more permanent.

She went into the kitchen, poured herself more coffee, and considered what was left in the pot. No, leave it, she thought, and turned her attention to the bottle of vodka on the sinkboard.

He must have fed her the Roofie at the bar. Otherwise she’d remember coming here. But there were two unwashed glasses next to the bottle, so they’d evidently had a nightcap before she lost it completely.

What a shock he’d given her! The touch, the unexpected warmth of his skin. And then his voice.

She hadn’t expected that.

She uncapped the bottle, opened the glassine envelope, poured its contents in with the vodka. The crystals dissolved immediately. She replaced the cap on the bottle, returned the empty envelope to her purse.

She made her cup of coffee last until he was out of the shower and dressed in khakis and a polo shirt, which was evidently what a Wall Street guy wore on the weekend. “I’ll get out of your hair now,” she told him. “And I’m sorry about last night. I’m going to make it a point not to get quite that drunk again.”

“You’ve got nothing to apologize for, Jen. You were running a risk, that’s all. For your own sake—”

“I know.”

“Hang on and I’ll walk you to the subway.”

She shook her head. “Really, there’s no need. I can find it.”

“You’re sure?”

“Positive.”

“If you say so. Uh, can I have your number?”

“You really want it?”

“I wouldn’t ask if I didn’t.”

“Next time I won’t pass out. I promise.”

He handed her a pen and a notepad, and she wrote down her area code, 212, and picked seven digits at random to keep it company. And then they kissed, and he said something sweet, and she said something clever in response, and she was out the door.

The streets were twisty and weird in that part of Riverdale, but she asked directions and somebody pointed her toward the subway. She waited on the elevated platform and thought about how shocked she’d been when she opened her eyes.

Because he was supposed to be dead. That was how it worked, you put the crystals in the guy’s drink and it took effect one or two hours later. After they’d had sex, after he’d dozed off or not. His heart stopped, and that was that.

It worked like a charm. But it only worked if you put the crystals in the guy’s drink, and if you were too drunk to manage that, well, you woke up and there he was.

Bummer.

Sooner or later, she thought, he’d take the cap off the vodka bottle. Today or tomorrow or next week, whenever he got around to it. And he’d take a drink, and one or two hours later he’d be cooling down to room temperature. She wouldn’t be there to scoop up his cash or go through his dresser drawers, but that was all right. The money wasn’t really the point.

Maybe he’d have some other girl with him. Maybe they’d both have a drink before hitting the mattress, and they could die in each other’s arms. Like Romeo and Juliet, sort of.

Or maybe she’d have a drink and he wouldn’t. That would be kind of interesting, when he tried to explain it all to the cops.

A pity she couldn’t be a fly on the wall. Would she ever find out what happened? Sooner or later, there’d be something in the papers. But by then she could well be a thousand miles away.

Because it felt as though it might be time to get out of New York. She felt at home here, but she had the knack of feeling at home just about anywhere. And a girl didn’t want to overstay her welcome.

FOUR

He was wearing a Western-style shirt, scarlet and black with a lot of gold piping, and one of those bolo string ties, and he should have topped things off with a broad-brimmed Stetson, but that would have hidden his hair. And it was the hair that had drawn her in the first place. It was a rich chestnut with red highlights, and so perfect she’d thought it was a wig. Up close, though, you could see that it was homegrown and not store bought, and it looked the way it did because he’d had one of those $400 haircuts that cost John Edwards the Iowa primary. This barber had worked hard to produce a haircut that appeared natural and effortless, so much so that it wound up looking like a wig.

He was waiting his turn at the craps table, betting against the shooter, and winning steadily as the dice stayed cold, with one shooter after another rolling craps a few times, then finally getting a point and promptly sevening out.