6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

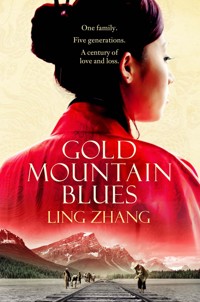

One Family. Five generations. An epic story of love and loss. China, 1879 With the Opium wars at their height, Fong Tak-Fat boards a ship to Canada, determined to make a life for himself and support his family back home. He will endure great hardship as he works to build the Pacific Railway and save every penny he makes to reunite his family. Canada, 2004 Amy Smith knows nothing of her family history, a secret her mother will not share, until she is summoned to her ancestral home in China to collect the forgotten belongings of family members whom she has never met. Can Amy finally unlock the door to her past? Telling the story of one family's journey through five generations and across the seas, Gold Mountain Blues is a heartrending tale of sacrifice, endurance, hope and survival.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

GOLD MOUNTAIN BLUES

LING ZHANG was born in 1957 in Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, China, and moved to Canada in 1986. She is the multi-award-winning author of five novels and four collections of short stories. She lives in Toronto.

This book is dedicated to the ONE who sheds perpetual light on my path when darkness seems to prevail and engulf me; to a man whose shoulders and arms are a safe harbour for my restless soul; and to a mother and a father who have taught me, through means I may not have understood in my youth, how to labour, to achieve, and to wait.

Ling Zhang

Contents

Preface

Note on Names

Prologue

1 Gold Mountain Dream

2 Gold Mountain Perils

3 Gold Mountain Promise

4 Gold Mountain Turmoil

5 Gold Mountain Tracks

6 Gold Mountain Affair

7 Gold Mountain Obstacles

8 Gold Mountain Blues

Notes

Afterword

List of Research Materials

PREFACE

The idea did not occur to me last year. Nor the year before.

The idea came to me in my very first fall in Canada, when I arrived in Calgary from Beijing, China, in September 1986.

It was a sunny afternoon. Leaves were turning a prism of colours for a final desperate show of life before winter killed them. We, my friends and I, were driving around the outskirts of the city to catch a last glimpse of autumn, when we had a flat tire. While waiting for assistance, I started to explore the surroundings. It was then that I noticed them, the tombstones, scattered among the knee-high grass and covered by moss and bird droppings. Most of them had Chinese names carved on them, some with fading pictures revealing the young but weathered faces with harsh cheekbones and hardly any smiles. Dates on the stones ranged from the second part of nineteenth century to the first part of twentieth century. These people died very young, possibly of unnatural causes. It didn’t take long for me to realize that they were early Chinese settlers, or coolies, as they had once been called.

What kind of lives did they lead in their villages in southern China? Whom did they leave behind when they decided to come to the “Gold Mountain,” a term they used to describe the wilderness of North America where gold deposits were discovered? What kind of dreams did they hold when they embarked on the harsh journey across the Pacific, not knowing whether they would ever return? What did they think when they first set eyes on the Rockies?

These questions started to form in my mind, dense and heavy. Of course I did not know that they would haunt me for many years to come.

A book. I could write a book about these people. I should, I told myself on the way home that day.

For the next seventeen years I flirted with the idea of such a book, but I was too busy. There were too many things needing my immediate attention: two academic degrees, a career as an audiologist, the right man to marry, a house I could call my own, a comfortable life in Canada. The idea of a Gold Mountain book got pushed down to the bottom of my to-do list. Every now and then, it would resurface, especially when I read in the news about the anniversary of the Vancouver riot, or the “Head Tax” compensation debate in the parliament, but I suppressed it as quickly as it appeared.

Then, in the fall of 2003, an unexpected opportunity presented itself to me. I was invited, together with a group of Chinese writers residing overseas, to tour one of the villages in Kaiping, Canton, China, known for its unique residential dwellings called diulau, literally translated as “fortress homes.” These houses were built with the money the coolies sent home, to protect the women and children they left behind, since this area was susceptible to flooding and bandits roamed the countryside. Since the coolies were scattered all around the world, the style of the fortress homes bore clear marks of the country where the money came from. One could easily detect baroque, Roman and Victorian characteristics weirdly moulded into southern Chinese architectural expression, not exactly a piece of eye candy.

Through the help of a smart local resident, we were able to slip into a fortress home abandoned for decades, and not yet remodelled for public display. On the third floor of the house, we found an old wooden closet. To my great surprise, I found a woman’s dress. It was pink, embroidered with faded golden peonies and full of moth holes. I uncovered yet another surprise—a pair of pantyhose was hidden in the sleeve. They looked thread thin from repeated washing, with a huge run spreading from the heel all the way up to where the legs part. While my fingers were tracing the run, I was struck with a sudden surge of energy, like an electrical current. I could hear my heart pumping in my chest, loud as thunder, as I stood there, quivering with awe.

What kind of woman was she who owned this pair of pantyhose almost a century ago? Had she been the mistress of the household? On what occasion would she wear this elaborate dress? Was she lonely, with her husband away toiling in the Gold Mountain trying to make enough money so that she could afford such expensive things?

Once again I felt the urge to find out the answers to my questions.

Another two years would pass before I finally committed myself to writing this Gold Mountain book, an interval allowing me to complete my third novel, Mail-Order Bride, and several novellas.

It was an all-consuming journey, digging into the rock-hard crust of history. I travelled to Victoria, Vancouver, and villages in Kaiping, China, trying to find people with knowledge, direct or indirect, of the era of my book. I frequented archives at all levels, both in person and through the internet, as well as university and public libraries. I found myself shaking with anticipation whenever I spotted a special collection on this subject, or heard a friend mention someone who was the offspring of a Pacific Railway builder. I spent many a sleepless night thinking about a better way to find the answers to my questions haunting me for so long. However, I never really found the answers. Instead, I found stories. From endless pages of books and many a conversation with descendants of Chinese coolies, stories started to surface of people who braved the ocean to come to a wild land called British Columbia, leaving their aging parents, newlywed wives or young children behind, to pursue dreams of wealth and prosperity that always eluded them: stories of champagne parties celebrating the last railroad spike, while the builders of the railroad, the Chinese coolies, were not even mentioned; stories of husbands and wives separated by the head tax, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the great vast ocean, who kept their marriages alive for decades with a strong will to build a future for their children. I heard stories of a lengthy and profound journey of two races finally becoming reconciled after a century of distrust and rejection.

The actual writing was not any easier. My train of thought was constantly interrupted and distracted by my addiction to accuracy: accuracy of historical fact and accuracy of detail. To find out a particular style of camera used in 1910s, for example, I would surf the net night after night to find a detail that would yield just a few sentences in my book. For information about pistols popular at the turn of century, I would engage my friends with military background in endless discussions until they absolutely dreaded my phone calls. I finally came to the realization that I was a hopeless perfectionist, something my friends had told me long before.

It was a cold December afternoon in 2008, a week before Christmas, when I stood up from my computer desk, stretching out my fatigued body with a sigh of relief; I finally had completed the draft of a novel entitled Gold Mountain Blues. Snow started falling. With Christmas music permeating the air, and juicy white snowflakes kissing my windowpanes with a gentle laziness, I felt the kind of peace that I had not known for a long while. I knew that I had accomplished a mission; I had given voice to a group of people buried in the dark abyss of history for more than a century, silent and forgotten.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank professor David Lai of University of Victoria, a member of Order of Canada, for his outstanding achievements in investigative work on the history of Chinatowns, who generously let me share his research on early Chinese immigrants in Canada; Dr. James Kwan, whose fascinating childhood tales in Kaiping village have given my inquisitive mind great pleasure—I hope I did not bore him to death with my endless questions; professor Xueqing Xu at York University and Dr. Helen Wu at University of Toronto for letting me share their access to university libraries, which helped to build the framework of my research; professor Lieyao Wang at Jinan University and his lovely graduate students for taking me to tour the villages in Kaiping and arranging for my accommodation there; my writer friend Shao Jun for accompanying me, like a true gentleman, on the tour; professors Guoxiong Zhang and Selia Tan of Wuyi University for sharing with me their in-depth knowledge of the contents of the Museum of Overseas Chinese; my dear friend Yan Zhang and her well-known newspaper The Global Chinese Press as well as the Chinese Canadian Writers’ Association for facilitating my research in Vancouver and Victoria; professor Henry Yu of University of British Columbia for sharing his knowledge in native Indian subjects; Mr. Ian Zeng and Mrs. Jinghua Huang for proofreading my first draft; Ms. Lily Liu, a well-published author herself, for sharing with me stories of her coolie ancestors; and many other friends who kindly offered me photos and information on related subjects. Last but definitely not least, I’d like to thank my family for constant emotional support without which I could not have endured the difficult and sometimes despairing journey of writing such an expansive book.

God bless you all!

P.S. Two years after the publication of Gold Mountain Blues in Chinese, I am very pleased to see the launch of its English edition in both Canada and Great Britain. I’d like to express my gratitude to my agent, Mr. Gray Tan, and the people he works with for placing their faith in me as an artist; to my translator, Ms. Nicky Harman, for her tireless explorations of the exciting but sometimes treacherous space between the two great languages in the world; to Ms. Adrienne Kerr for helping me through every step of the way with her in-depth knowledge as a seasoned editor; and many friends whom I can’t possibly name in such a limited space for their unfailing emotional support during some of the darkest moments in my life as the book was being born.

NOTE ON NAMES

Surnames come first: Fong or Tse or Au or Auyung.

Given names have two parts: a generation name (the same for each member of the same generation of a family) and a personal name, which comes last. People are known familiarly either by their nickname or by a diminutive formed by adding Ah- to the personal part of their given name. So, Kwan Suk Yin (surname Kwan) is known by her nickname, “Six Fingers,” or Ah-Yin (by her husband) or, later in life, Mrs. Kwan.

Cantonese and Mandarin (pinyin romanization)

We have used a Cantonese spelling for all names of people who spoke Cantonese to each other, and local places in South China. For national figures (for instance, Li Hongzhang) and names of provinces, we have used Mandarin pinyin romanization. The exception is the Chinese Revolutionary commonly known in the West as Sun Yat-sen (Mandarin pinyin: Sun Zhongshan).

TABLE OF MAIN CHARACTERS

PROLOGUE

Guangdong Province, China, in the year 2004

Amy elbowed her way through the bustling throng in the arrivals lounge at Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport and stopped in front of two gentlemen holding a sign which read “Ms Fong Yin Ling.” They stared at her, dumbstruck. What on earth was this foreigner with her chestnut hair and brown eyes doing here?

The Office for Overseas Chinese Affairs had sent two men to pick her up: Ng the young driver, and an older one, the head of the local O.O.C.A., Auyung Wan On. “You, you, you’re.…” Ng began, stuttering in flustered astonishment. He found he was speaking to her in English.

“That’s me,” Amy said in decent Chinese, indicating the sign. It was enough to reassure Ng and Auyung and together they escorted her out to the airport carpark.

Although it was only May, the weather was blisteringly hot. To Amy, accustomed to the lukewarm sunshine of Vancouver, the sun in Canton seemed to be full of tiny hooks which pricked her painfully all over. She got quickly into the black Audi and waited for the chill of the air-conditioning, wiping her sticky forehead with a tissue.

“How far is it?” she asked Auyung.

“Not far. The car can easily do it in a couple of hours.”

“Are all the documents ready? I’ll sign them as soon as we arrive. Can you get me back to Canton this evening?”

“Won’t you stay one night? That way you can check over the antiques you’ve inherited tomorrow morning.”

“I can’t see the point. Get someone else to box them up and ship them to me.”

Auyung looked taken aback for a moment. Then he said: “No one’s been in the building for decades. There’s a lot of stuff which dates from the time it was built. You need to make an inventory because they’re antiques. Apart from what is strictly personal and private, we hope everything will be left for display. Of course, you can take photographs to keep as mementoes—that’s clearly stated in the contract.”

Amy sighed. “Looks like I’ll have to stay one night then. Have you booked me into a hotel?”

“Yes, that’s all fixed,” said Ng from the front seat. “It’s the best one in town. Of course it’s not up to Canton standards, but it’s very clean, there are hot springs and it’s got internet.” Amy said nothing, and just sat fanning her sweaty face with a book.

It was quiet in the car. Auyung broke the silence: “Mr. Wong, our director, has been expecting you since last spring. He had plans to entertain you himself. Then we heard you were ill and the trip was postponed a few times. Now you’ve arrived, but Mr. Wong has just gone to Russia on business. He left a message asking you to wait until he returns. You’re the only one left out of all Fong Tak Fat’s descendants. It wasn’t easy tracking you down.”

Amy gave a laugh. “I’m not the Fong Yin Ling your director was expecting. She’s my mother. She’s still ill, so she sent me instead.” She got a business card out of her handbag and handed it to Auyung. It was in English, but he could read it:

Amy Smith

Professor in Sociology

University of British Columbia

Auyung tapped Amy’s card lightly against the palm of his hand. “Now I understand,” he said, “no wonder.…”

“Do I really look that old?” asked Amy.

Auyung laughed. “It’s not that. I just couldn’t understand why Fong Yin Ling didn’t want to go and pay her respects at her grandmother’s grave.”

Amy looked blank for a moment, then remembered the bag her mother had pushed into her hands before she left.

Amy’s mother had been getting letters from an office in Hoi Ping for over a year. They were official letters stamped with the municipal red seal and were about her family’s home. The Fongs’ was one of the oldest diulau, or fortress homes, in the area, they said. It was currently being registered as a World Heritage Site, and was to be renovated and turned into a tourist attraction. The letters requested the Fong descendants to return and sign an agreement assigning trusteeship to the regional government.

As a small child, Yin Ling had been brought home by her parents on a visit and had lived in the diulau for two years. She was too young for it to make much of an impression on her, and the passage of some eighty years had almost completely effaced the memories. The Fong family had not lived there for many years, and besides, the use of the word “trusteeship” sounded too much like compulsory repossession. So Yin Ling had simply thrown every letter into the wastepaper bin without saying a word to anyone about them.

To her surprise, the authorities in Hoi Ping had been persistent, sending more letters and even making several international phone calls—though she had no idea how they had found her number.

“This is a heritage site, nearly a hundred years old. How can you bear to see it crumble to dust like this? If it’s taken into public trusteeship, it will be restored to the way it was, and will be a fitting monument to the Fongs. You won’t need to spend a cent, or put in an ounce of effort, but you retain all the rights. It’s the perfect outcome.”

The words, constantly repeated, gradually wore down Yin Ling’s resistance. However, just as she was warming to the idea, she fell ill. She had been confined to bed for over a year now.

Up to age seventy-nine, Yin Ling had been as unmarked by age as a tree luxuriantly covered in pristine foliage. But then overnight, it was as if she had suddenly been felled by a hurricane.

It happened on her seventy-ninth birthday. She had invited some of her usual mahjong friends to eat at an Italian cafeteria, and then back to her house for a game of mahjong. When Yin Ling was young, she used to get annoyed watching her mum playing mahjong with her cronies, but in old age her own few friends were all mahjong players. Amy had not been there that day and, without her daughter present, Yin Ling really let her hair down, chain-smoking and knocking back the booze until she was uproariously drunk. The party did not break up until midnight. Yin Ling went to bed that night but did not get up in the morning. Overnight she suffered a stroke.

After the stroke, Yin Ling could not speak English any more. As a child she had attended the city school, and all her boyfriends had been White Canadians, so whether at home or at work, she rattled away in English. Now, bizarrely, it was as if some tiny perverse hand had meddled in her brain, erasing it all. When she woke up in the hospital and heard the doctors and nurses talking to her, she looked completely blank. And her speech, when it came, was so garbled it was incomprehensible. At first, they thought the speech centre in her brain had been affected. It took several days for Amy to solve the mystery: Yin Ling’s squawks were actually Cantonese—the Cantonese her granddad had spoken at home when she was a child.

Yin Ling was a different woman after her illness. She left hospital for a convalescent home and then, a few months later, was transferred to a nursing home. Every time she arrived at a new place, there were furious rows. Amy pulled out all the stops and eventually got her mother into a Chinese nursing home. Here she could make herself understood, and things seemed to calm down.

One day, Amy was in the middle of teaching a class when she received an urgent phone call from the home. She dropped everything and rushed there—to see the old lady strapped into a wheelchair with a leather belt, her face streaming with tears. Her mother got up that morning, Amy was told, and suddenly started yelling that it would be too late, too late! When the nurse asked what would be too late, she made whooping sounds and, when this was not understood, Yin Ling picked up her walking stick and bashed the nurse in the face with it.

“We can’t cope with a patient like this—it’s not safe for the nurses or the other patients,” the director told Amy.

Seeing her elderly mother in the wheelchair, straining to break free of the belt and foaming at the mouth like a fish tied in twine and gasping for breath, Amy fell to her knees beside her and wailed. “Oh God, whatever do you want me to do with you!”

Yin Ling had never seen her daughter cry like this before. The shock seemed to calm her down. Then, after a moment, she put out her hand and said to Amy: “You go.”

In Yin Ling’s palm was a letter, crumpled and damp, and stamped with a Chinese red seal.

Amy had to read it through a number of times before she understood what it meant. “OK,” she sighed, “I’ll go, but you have to promise not to get into fights with the nurses.” Her mother grinned, showing tobacco-stained teeth.

“And don’t ever think kicking up a fuss will make me take you home. I’ll just take you straight to a mental hospital. If I can’t keep you under control, then they will,” Amy finished fiercely.

“Could you move her into a single room—keep her away from other patients and give her a nurse of her own?” she begged the director. “I’ll take care of the costs. Assess the situation in a month when I’m back from China and then come to a decision, OK?” She put on a brazen smile.

Amy left the nursing home that day cursing under her breath. Spring had come to Vancouver in full force. The grass was lush after showers of rain, the climbing roses against the white walls of the home were touched with splodges of vivid scarlet and birds sang shrilly in the trees. But Amy paid absolutely no attention. Her mother, Fong Yin Ling, had looked so small and shrunken in her wheelchair that she might have been a wizened nut blown down from a tree by a gust of wind.

The journey took much longer than Auyung said. They bumped along the potholed road, past building sites and roadworks until finally, towards evening, they arrived at the village. Amy felt as if all the bones in her body had been jolted around in the car.

Every wall in the village was plastered with gaudy bank advertisements offering the best rates for overseas remittances. “Are they trying to hijack each other’s customers?” asked Amy.

“When the oil flows like this, who’s not going to take advantage of it?” said Auyung. “Every dog in town has a relative overseas. In the old days it was the seabirds and the town horses with their shoulder poles who delivered the ‘dollar letters’ to the villages. Nowadays the money is wired back home. It travels in a different way but it’s the same thing.”

Amy knitted her brows: “Is that supposed to be Chinese? I can’t make head or tail of what you’re saying. What seabirds? What horses?”

“The seabirds were the people who carried dollar letters back by boat, the horses were the men who delivered the letters to the villagers.” Auyung glanced at her. “So you’re beginning to get interested.…” “I’m interested in any sociological phenomena,” replied Amy tartly, “whether it’s over here or back home, there’s no difference.”

The Fongs’ diulau was some way off the road. The car set them down and they had to walk the last stretch.

The track ran alongside an abandoned factory and was so overgrown it looked as if no one had walked it for years. The banana trees had been left to fend for themselves, and their dead leaves were strewn on the ground in a thick layer. Although the sun was still bright, the grass was full of whining mosquitoes. They bit Amy through her clothes, and she felt lumps coming up all over her.

Auyung gave her some mosquito repellent to rub on and shouted angrily at the village cadre coming to greet them: “I told you ages ago someone was coming to visit. Why didn’t you clear the track? You’re so busy making money that you can’t spare a minute for anything else!”

The man bit back an angry retort and gave a loud laugh instead. Then he turned and bellowed at the crowd of women with babies in arms looking on curiously from a safe distance: “What do you think you’re gawping at? Haven’t you been taught how to behave in front of foreigners?” The women giggled nervously but continued to tag along behind them.

“It’s been so many years since Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. How come your grandfather and your mother didn’t want to come back for a visit?” Auyung asked Amy.

“Mum said that Granddad died just as China and Canada re-established diplomatic relations. Granddad had a few friends who made inquiries about getting a visa to go back but he and Mum decided they couldn’t go.”

“Why?”

Amy stood still and looked at Auyung levelly. “I was hoping you would tell me that.”

After a moment’s silence, Auyung said: “Everything was crazy back then. Not just the people, even the river in the village went crazy—there was torrential rain and it rose to levels not seen in a hundred years and flooded the entire village.”

“Haven’t you got a better explanation than that? I am a sociologist, in case you’ve forgotten,” Amy replied coolly.

“Of course. But now isn’t the moment to talk about it. By the way, I’ve done studies of overseas Chinese too so we have quite a lot in common.”

“Mr. Auyung’s a professor too, Ms. Smith,” Ng the driver chipped in. “He’s made a special study of these diulau homes. That’s why the Office for Overseas Chinese Affairs contracted his service so he can deal with the preservation of these homes.”

Amy concealed her surprise. “So then you’ll know why in a place where every inch of land is worth its weight in gold, this place is so desolate, won’t you?”

Auyung gave a slight smile. “Do you want the textbook answer or the local tales?”

Amy smiled back. “Both please, I’d like to hear both.”

“The textbooks will tell you that this land suffered heavy industrial pollution, and was abandoned because crops can’t be grown on it.”

“And the other version?”

“The locals say that things happened here, back in the past, and there have been supernatural phenomena, so no one wants to build here.”

“You mean it’s haunted?”

Auyung shook his head. “No, that’s not what I said. Of course, you’ve every right to interpret local tales just how you wish.”

Amy burst out laughing. This old boy was certainly interesting. It might not be such a bad idea to stay a couple of nights.

They stumbled down the track and arrived at the building. In fact, it had been clearly visible from a distance, but it was only now that they were right in front of it that it revealed its age. It was a five-storey Western-style concrete building, south-facing, with overhanging Chinese-style eaves on all sides. There were numerous windows, all very narrow and so weather-beaten that they had lost their original shape. They looked more like cannonball holes than windows. The iron bars fitted to every window and door were heavily rusted. There were Roman-style mini-columns under the eaves, and the columns and windows were all covered in carvings now scarcely visible.

Auyung brought a large stone over and stood on it. Extracting some sheets of newspaper from his briefcase, he began rubbing the lichen and bird droppings from the door. Eventually, a name appeared: “Tak Yin House.” The characters were carved in the Slender Gold style of the Song dynasty, and in the deeper parts traces of pink could be seen. Originally, no doubt, they would have been painted vermilion red.

The door was narrow and covered with an iron grille with locks at the top, middle and bottom, called “heaven, earth and middle” locks, as Auyung explained. The heaven and earth locks were operated from the inside and, if not bolted, the door could simply be pushed open. Only the middle one was a real lock. Originally, it had been around four inches across but had expanded considerably with the rust. “Do you have a key?” Auyung asked the cadre.

“No one’s been in here for years. Of course we haven’t got a key” was the reply. “Anyway now the owner’s turned up, she can break the lock herself.”

Ng went back to the track, picked up a sharp stone and handed it to Amy. The lock was very old and broke after a couple of blows, but the door was sturdier and juddered before finally opening a crack. With a grating cry, a sooty-black bird flew out, its wings nearly grazing Amy’s head. Amy’s knees gave way and she sat down on the ground, clasping her hands tightly over her chest, her heart thudding.

The village cadre looked uneasy. “The rites … has she performed the ancestral rites yet?” he whispered to Auyung.

“Whatever’s the matter?” Auyung said. “Her ancestors have had a long wait for her to get here. They’ve scarcely had time to rejoice, let alone be offended. The rites can wait until tomorrow, she hasn’t been to the graves yet.”

“I’m off outside for a smoke,” said the cadre, clearly alarmed. And he waited at the entrance as Auyung led the way into the house.

As she stepped over the threshold, Amy heard the scrunching of dirt under her feet. The glass in the windows was broken and the evening sunshine streamed in, turning the dust particles to gold. Amy stood still. Gradually she began to make out the interior; it contained no furniture except a water barrel with a large crack down the side.

“The kitchen and the servants’ rooms were on this level,” explained Auyung, “the Fongs’ rooms and bedrooms were all on the floors above.”

They made their way over to the stairs.

Its treads had collapsed in so many places that the staircase looked like a ribcage with the intestines rotted away. Auyung and Amy cautiously made their way up, testing each step as they went, until they finally arrived at the second floor. Against the wall facing them was a long wooden table, its paintwork faded. Two round objects stood on it. Amy took a closer look and realized they were copper incense burners, their elegant shapes ravaged by the thick layers of verdigris which covered them. In a small alcove in the wall stood a statue of Guan Yam, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. Her head and shoulders had been lopped off, and only the fingers holding the lotus flower remained as a reminder of her compassion. The paint had worn off the characters engraved above the statue and only a few could be made out:

Candle … create … flower

… incense … out … peaceful home

Under the statue there was a wooden memorial tablet with no paint left on it at all. Rainwater had leaked in and most of the tablet had disintegrated. Only at the far right side were a couple of lines of characters still legible:

illustrious twentieth generation … ancestors

father, head of the family, Mr. Fong Dik Coi

mother, Mrs. Wen, mistress of the house

“This was where your family used to worship the spirits of the ancestors,” said Auyung.

What looked like broken sticks of furniture lay in a heap on the floor. Amy turned them over with her foot, raising a cloud of dust which caught in her throat and made her cough. Auyung pulled out a stick and passed it to her. It looked something like a flute, but thicker and longer. A fine chain was attached to the body of the pipe and in the middle was a raised bowl with an opening. Amy blew away the dust and saw underneath a yellowish pattern, rather like vines twisting around a tree branch. She flicked it with her finger and it made a pinging sound. It was not made of bamboo.

“This is an opium pipe. It’s carved from elephant ivory, and it’s worth a fortune,” said Auyung.

1

Gold Mountain Dream

Year eleven of the reign of Tongzhi to year five of the reign of Guangxu (1872–1879)

Spur-On Village, Hoi Ping County, Guangdong Province, China

The village lay within the boundaries of the township of Wo On in Hoi Ping County. Newfangled as its name sounds, the village was actually a couple of hundred years old. Legend has it that in the reign of the Qing emperor Qianlong, two brothers fled from famine-stricken Annam and settled here with their families. They cleared the land, tilled the soil, raised cattle and pigs and within a decade or so were firmly established. As he lay dying, the elder brother issued an exhortation to the whole family—they were to spur themselves on to ever-great efforts. Thus the village acquired the name Tsz Min, or Spur-On Village.

By the reign of Tongzhi, Spur-On Village had grown into a sizeable place, with over a hundred families. There were two clans: the Fongs, the dominant family and descendants of the Annamese brothers, and the Aus, outsiders who had come from Fujian. They were almost all farmers, with the difference that the Fongs owned large, contiguous fields while the Au clan, who had arrived later, cultivated scraps of land which they cleared at the edges of the Fongs’ fields. Later the two families began to intermarry, the daughters of one with the sons of the other. As the families merged, so, gradually, did the fields, and the differences in status between the Fongs and the Aus blurred too. This did not last: events took place which sharpened edges previously blunted … but that was not until much later.

One boundary of the village was marked by a small river, while at the other end was a low hill. The fields lay in a depression between the two landmarks; after years of intensive cultivation, they were fertile and productive and, in good years, their produce was enough to support the entire village. In times of drought and flooding, however, sons and daughters were still sometimes sold as servants.

Apart from growing crops, the people of Spur-On Village also reared pigs, grew vegetables, and did embroidery and weaving. They ate a little of their own produce, but most was taken to market and the cash used to buy household goods. Almost all Spur-On families had pigs and cattle, but there was only one slaughterman among them: Fong Tak Fat’s father, Fong Yuen Cheong.

Three generations of Fong Yuen Cheong’s family had been slaughtermen. As soon he was weaned and able to toddle without falling over, Fong Tak Fat would squat bare-bottomed next to his father and watch him butcher pigs. The knife went in white and came out red but he was not the least bit scared. “The furthest I’ve been to butcher pigs is ten or twenty li,” his father boasted to the other villagers, “but our Ah-Fat will travel thousands of li to butcher pigs.” Only half of this boast was correct, the bit about thousands of li.1 He was wrong about the butchering because before the time had come for him to hand his son the knife, Fong Yuen Cheong died.

Yuen Cheong’s branch of the Fong family had been getting poorer with every generation. His father had still owned a few mu2 of poor land, but by Yuen Cheong’s time, they were reduced to renting a few patches here and there. After the rent on the land had been paid, the yield was only enough to fill half the family rice bowl. They relied on Yuen Cheong’s butchering work for the other half. If he killed his own clan’s pigs in Spur-On Village, he received only the offal. It was when he worked for families who were not related, like the Aus, or who were from other villages, that he could earn a few coppers. So the family rice bowl sometimes stayed half-empty. It depended on the weather, the number of animals to be killed, the agricultural almanac and the cultural calendar—at propitious times when there were more weddings and more houses being built, more animals were killed.

Beginning in year ten of the reign of Tongzhi, there were two successive years of drought. The river which ran past the village dried to a strip of ooze over which clouds of insects swarmed as the evening sun went down. The fish and shrimps were nowhere to be seen. The parched earth, like an infant mewling for the breast, longed for rain which never came. The harvests were poor and few pigs were killed. It got harder and harder for Fong Yuen Cheong to feed his family.

But then Yuen Cheong’s fortunes changed. It happened one market day in Tongzhi year eleven.

He got up at the crack of dawn that day and killed a yearling pig. He had wanted to keep it until the end of the year and cure its meat but he could not wait. The family had seen not even a drop of lard for too long. The pig could not wait either—by now it was hardly more than skin and bones. When he had killed it, he set the head, tail and offal to one side and cut the body and legs up into several pieces to take to market. He hoped he could buy a few lotus seed paste cakes with the money; his younger son, Tak Sin, would be a year old the day after tomorrow. They could not afford a birthday banquet but at least they could share the pastries among the neighbours.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!