4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Odyssey Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

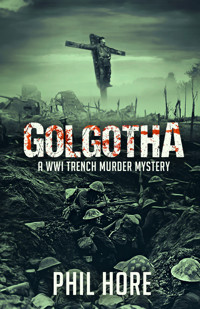

1916, the Western Front.

There are some crimes that transcend the horrors of war, and the rumour of a soldier being found in no man’s land crucified to a church door threatens to cause a mutiny in the trenches. To placate the troops, allied HQ orders four soldiers pulled from the ranks of each army to investigate the crime and bring the perpetrator swiftly to justice. What a Canadian ex-Mountie, an Australian beat cop, a constable from Scotland Yard, and their military intelligence commander discover will not only save the lives of the comrades, but may well save the entire war.

Full of factual events and historic occurrences, Golgotha looks into one of the darkest events to occur during the First World War.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Published by Odyssey Books in 2021

Copyright © Phil Hore 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

www.odysseybooks.com.au

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 978-1922311160 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1922311177 (ebook)

Golgotha

Phil Hore

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Epilogue

A historical conclusion

Share your thoughts with us

About the Author

Also by Phil Hore

Chapter One

Armentières 1916

A shell screamed overhead and impacted somewhere behind the ruined section of the trench Sergeant Hank Ash and the rest of his squad were pinned down in. All sported the cloth patch of the 1st Australian division—a white square surrounded by a blue square. The unit had been gathering a fierce reputation since entering the war. Most of the soldiers also wore two chevrons on the lower sleeves of their jackets, each recording a year served since boot camp. The stripes heralded these were Gallipoli veterans—an accomplishment that had begun taking on hallowed status amongst arriving new recruits.

Across the battlefield, artillery shells tore at the ruined countryside, along with the vulnerable flesh of anyone exposed to this manmade maelstrom. Any organised structure to the Australian attack had long since disintegrated under the German defensive onslaught, and the fighting was dissolving into individuals making sure the men under their immediate control continued to move toward their objective.

‘How many grenades we got, Red?’ Ash yelled at one of the men behind him.

In Gallipoli, the Australians had proven themselves unique, as every soldier not only had upcoming battle strategies explained to them, but they were encouraged to show initiative and exploit any opportunity that arose during the chaos of combat. This simple step meant that instead of an attack force grinding to a halt with the death of an officer, each trooper knew what needed to be done and had the ability to get on and do it. This was a skillset the Diggers had brought with them to the Western Front, and though new to the style of trench warfare fought in France, the savvy Australians were catching on fast.

Throughout the shell hole, men patted themselves down and held up fingers to indicate what each was carrying. After a quick count, the South Australian nicknamed ‘Red’, for his almost-white blond hair, yelled back, ‘About thirty, Sarge.’

Lying on his back to keep as low as possible, Ash pulled a small mirror from his breast pocket and angled it so that he could peer over the lip of their makeshift foxhole and examine the obstacle before them.

Called ‘Pinchgut’ by the Australians stationed nearby after Fort Denison in Sydney Harbour, the enormous concrete bunker sitting on top of a ridge over the village of Pérenchies was their target. The village had been a quiet burg before the war, crowning a small crest with a scenic view of the surrounding countryside and the distant city of Lille. When the war began, this elevation proved beneficial to the invading Germans, and they had fortified the area around the town, which became the key to their defence of the region. Not only did it supply the Germans stationed there a view of the Allied trenches stretching out across the countryside, artillery spotters also used the unobstructed view to direct accurate fire against any enemy movement on the low-lying lands. Worse, recently an electric searchlight had been placed along the stronghold, and this was often turned on the Allied lines at various times at night, making a sortie into no man’s land a fatal one.

Allied command was aware of the danger the position presented and kept promising to send wave upon wave of screaming men charging up toward Pérenchies. No attack was ever organised, however, and local Allied troops had taken it upon themselves to try to knock out Pinchgut during a series of night attacks. Each time they were driven out by ferocious German counterattacks.

Then the Australians arrived.

Though no braver than the troops of other nations fighting along the Western Front, what made the Australian men different, and ultimately more dangerous, was their esprit de corps. Where most Allied soldiers were conscripts, forced by their government into a uniform and to carry a gun onto the battlefield, every single Australian was a volunteer. They had not been conscripted and pushed toward the front lines—the men from Down Under had chosen to be there.

Though they had supposedly been sent to the quiet Armentières region to learn how to fight and survive along the Western Front, having their positions shelled and bombed, and their men constantly sniped at had left the Aussies in a serious mood to remove this thorn from their side.

The battle for control of no man’s land then intensified as the jovial Australians took on the challenge as though it were a new sport. For some time, the most professional units looked at the territory between both armies as theirs, and they would send out heavy patrols to take control of no man’s land once night fell. Here, they would try to capture enemy soldiers to interrogate, ascertain what the enemy was up to in their own lines, and perhaps even lay out a listening microphone and trail its wire back to their own trench. The idea was to take control of the unclaimed region and make it fatal for an enemy unit to try the same tactics against them.

There was also the act of souveniring. The Australians were keen to get their hands on German weapons, uniforms, and equipment to show the folks at home, and this added incentive made them ferocious patrollers into no man’s land. This theft became so epidemic that after several months being stationed across from the Aussies, many German units began to complain that something needed to be done after they continually entered their trenches in the morning to find much of their equipment gone.

It was during one such foray that someone in the Australian lines had decided it would be a good idea to secretly head over to the German lines and get rid of the searchlight and destroy Pinchgut for good. This little sortie soon grew into a small attack when the extent of the defences around the position were mapped, and other squads were asked to join in the fun.

Soon, hundreds of Australians had either snuck in to attack Pinchgut or stood ready in their own trenches to help withdraw the attackers if things got too hot. One of those squads was Ash and his men, who had managed to sneak most of the way across no man’s land before hell erupted around them.

The German defenders must have had someone manning a listening post somewhere and had sent a warning about the attack, as the Germans suddenly opened fire, but their defence was pretty light and the Australians believed they still had an opportunity to pull off their mission. Confident his men would know what to do when the time was right, Ash worked out a quick plan of action against the stronghold, then asked the nearest troopers in the shell hole what they thought. As he explained his idea, he wiped away the tears streaming from his eyes with a sleeve, caused by a teargas shell that had fallen short and exploded nearby. Everyone had breathed a sigh of relief when they’d discovered the gas wasn’t one of the deadlier flavours.

Night had fallen as the men crawled into their current position, and all were dirty from head to toe, yet the brief flash of bright white teeth from their grins told Ash the squad was ready.

‘Okay, boys, let’s go.’

With three men tossing grenades before them, the rest of the squad charged one side of Pinchgut, toward a spot Ash noticed the German guns had trouble traversing to cover. As the detonating bombs made the enemy think twice about leaning over the top of their trench, the Australians ran forward. Many swept the enemy line with fire from the Lewis light machine guns they were carrying. Between this hail of bullets and the barrage of bombs, the squad managed to reach the outermost edge of the main trench leading to the back of Pinchgut and slide in.

A few surviving Germans rushed the Diggers, but a volley of Lewis fire and a few well-placed Mills bombs forced them back. The foothold the Australians had created was soon widened as other soldiers, seeing Ash and his men breach the trench, rushed forward. Hundreds of Australians and even a few Canadians from a neighbouring trench began fighting through the German lines, overwhelming the defenders and forcing their way closer and closer to the concrete bunker.

Within the constraining depths of the trench, the battle devolved into a hand-to-hand fight. Like some chivalrous battle of old, the large bulky guns and modern explosives were ignored for fear of killing friend along with foe. Instead, more traditional weapons were used; roughly made clubs and maces were pulled from backpacks, along with knives, bayonets, and knuckledusters. All were put to good use.

Foot by foot, the troopers bludgeoned their way through the defenders and soon made it to the rear of Pinchgut. A few men scrambled up the concrete sides of the bunker, pushing Mills bombs and jam-tin grenades through the gun-slits and shell holes. Inside, muffled explosions and high-pitched screams followed, yet the fight raged on.

Those soldiers closest to the bunker mopped up the few remaining Germans about the area, while the Allied officers who’d survived the assault began organising what troops they had left for the inevitable enemy counterattack.

Overturned Maxim machine guns were repaired and repositioned to cover any path leading toward the bunker from the German rear, while new trenches were dug and holes in the defences filled. Men were sent forward to watch for any German movement, and reinforcements and supplies were called forward from the Allied lines.

If the enemy wanted the position back, they were going to have to fight for it.

Ash and his unit had been amongst the first to enter the bunker, and the gruesome spectacle of what their attack had achieved greeted them in the form of the broken, shattered, limbless bodies of its former occupants. While checking to see if anybody was still breathing, the Australians rifled pockets and backpacks for anything of value, all the while pushing deeper and deeper into the structure.

The few Germans to survive the attack and determined to fight on were quickly dispatched with hand grenades and pistol fire. The bodies were carefully collected in case of boobytraps and thrown out into no man’s land. A small team of men carrying a spool of thick wire between them were ordered back toward their own lines, and carefully they began laying a communication cable to the bunker.

Within an hour, the troopers from the 1st Australian Division were communicating their success firsthand through these field phones, though most of what they said and what was said to them was lost in static and other background noises. They managed to report that the men had pushed further along the edges of the former German lines, rolling up the Kaiser’s defences like an old, dirty carpet. The entire town of Pérenchies now lay under their control, and its new defenders awaited orders from headquarters. When these came, they were exactly what the tired, bloody Diggers didn’t want to hear.

‘We have to hold until relieved,’ the newly arrived Colonel Blackburn exclaimed to anyone close enough to hear. A former lawyer from South Australia, he had been unaware of the attack, but was professional enough to rally what men he had to exploit the hole in the German defences. He was also more than aware that the bush telegraph of gossiping soldiers meant all his men would soon hear about the command.

Cursing and bitching in the way all soldiers have since the dawn of time when feeling hard done by, as they moved back to man what defences they could, the Australians took a few minutes to catch their breaths and begin the long, cold wait for a German response.

They didn’t have to wait long.

Well behind the German lines, information was flowing in about the attack. Some was comprehensive and useable, some scrambled and full of panic. What the German commanders could tell was that an unknown number of Allied troops were moving from a region called Armentières, their forces reportedly having penetrated a limited number of places. Reserve units were already moving to stop any further intrusions, but this only created further confusion when no such attacks arrived along the rest of the front. Paranoia of the unknown was taking its hold on the German army.

Clear communication became as difficult for the Germans as it was for the Allies when more reports flowed in. Some were accurate, most were not. Some were old and out of date, while others were fresh and precise. This meant it wasn’t until morning’s first light that there was a clear picture of what had occurred. Almost everywhere the German line had held, except at Pérenchies, the Allies had taken over the entire section. As the sole Allied gain, the next move for the Germans was clear. Every gun, every cannon, and every free soldier was lined up against what remained of the fortress above the enemy-held French village.

The order was then sent to the entirety of the 4th German Corp that, as one of the most dominating features on the Flanders battlefield, Pérenchies was to be retaken at any cost.

Chapter Two

Pérenchies

Ash and his squad had just finished excavating a part of the former German trench and were looking for water to refill their canteens when the first shell screamed out of the night sky. This smacked into the earth with a deep whumf, and though falling some distance away, the sheer size of the explosion rattled the air in the men’s lungs. Reacting on sheer instinct, the men dropped into the trench to ride out the bombardment.

The German engineers and artillery units of IV Corps knew the location of every strongpoint and trench in their former defences, and they zeroed in on these positions with deadly accuracy. Hundreds of shells thoroughly pounded the hill, and once they felt nothing more could be achieved there, they moved their guns to the countryside surrounding the village. The hope was to catch any units moving across the open terrain to support what Allied troops had survived the bombardment. This action was so effective that very quickly this approach was known as ‘Dead Man’s Road’ to the Australians.

With the bombardment finally moving away from them, Ash and his men began digging themselves out from the mountain of fresh dirt that had been thrown across the trenches. Many of those who had sheltered in the rough holes cut into Pinchgut would remain buried forever.

In just a few hours, the barrage changed the landscape surrounding the ridge, making it look more like the scarred face of the moon. It had the desired effect, though, as many of the new defensive points were useless after being torn open and exposed by an explosive shell.

Seeing the danger, Ash urged his men into action. ‘Move, you bastards. We have to get a new trench dug.’

‘But this hole is okay, Sarge,’ one voice moaned from the rear.

‘Grab a shovel and start digging before I dump you back down there and leave you for good,’ Ash threatened, pulling his own spade from his pack.

The handful of soldiers followed suit and retrieved the large shovels that partly led to their nickname ‘Diggers’ and, mirroring their leader, began flinging dirt high as they worked a new trench. No one was sure if the name originated from the shovel or the Australian habit of wearing the detached tool head in a bag over their groin for protection. Fruitlessly, many British officers had bawled out the Australians when they arrived in Europe for not wearing the shovel and its bag correctly, attaching it to the belt over a buttock cheek. Instead, the Diggers wore it across the groin for the obvious protection a large chunk of steel could provide.

As they dug, the troopers positioned themselves in such a way that they could look out for a German counterattack and ensure they were not exposed to snipers. With the new trench completed, Ash ordered some of his men to reposition a nearby Maxim machine gun, while the rest were sent out to look through the other collapsed trenches for any survivors buried within the mud and clay. While they worked, several runners appeared from their own trenches; some carried messages, other tins of bully beef or boxes of ammunition. The couriers also supplied the latest gossip from across the battlefield, including a rough tally of who’d been ‘knocked’ from the division and those who’d been wounded. As it always seemed to be these days, the news was depressing as far too many of those killed were Gallipoli veterans. The survivors of the attack in the Dardanelles were becoming a rare breed on the fields of the Western Front.

On hearing about the death of a fellow sergeant he’d been close to, Ash picked up a dirt clog and in frustration threw it at a group of passing German prisoners being escorted to the rear lines. Never intending to really hit anyone, when the clog burst on the head of a short German with a huge handlebar moustache, a soldier guarding the prisoners yelled out:

‘Oi! Cut that out.’

Sheepishly, Ash held up a hand in apology. He then turned toward the grinning faces of his men.

‘Next time pull the pin, Sarge.’ Red laughed, lobbing another as though it was a hand grenade. ‘They’re no better than a potato otherwise.’

The dirt clog sailed through the air and landed just as a German shell dropped out of the sky and exploded. Ash dived into the trench with his troopers, snatching for his gun as he tumbled in. As shrapnel and debris filled the air, Ash strained his ears, trying to hear above the whistling, concussive booms and screams of injured men for the one thing everyone in the trenches feared above all else. Soon enough he heard what he was listening for.

Starting soft, but growing louder and more intense, the sound of the long-awaited German counterattack grew nearer. Tens of thousands of men with bayonets drawn, streaming across the rubble and cratered French field at the Australian lines, was a cacophony that even an artillery barrage could not hide completely.

At some unseen signal, the salvaged Maxim guns opened fire, with the stream of death spitting out of the large guns scything through the massed Germans. Gaps began appearing in their ranks, yet still they bravely charged forward, trying to retake their former position.

An artillery shell screamed out of the heavens and hit just in front of the trench Ash and his men were fighting in, sending a tidal wave of dirt rolling over the foxhole. It only took a few minutes for the soldiers to claw themselves out of the loose dirt, but by then the German attack had moved closer.

Looking around to ensure everyone was free and armed, Ash yelled, ‘Up and at ’em, boys.’ He then aimed over the trench and fired into a large mass of enemy nearby. Next to him, a line of 303s and Lewis guns opened up, adding to the carnage amongst the German troops still moving up the hill.

Loading and firing as fast as possible, the troopers never noticed when the first attack faltered, and they began fighting a second, then a third wave. Time and thinking had ended, now replaced by the simple act of fire, load, and fire again.

Further toward the town, the remaining defenders began to tire, allowing the massed German advance to creep closer and closer. From simple dirt grey figures, individual faces moved into focus, only to be cut down by an Allied bullet. Despite the butchery, in a number of places the Germans managed to enter the Pinchgut trenches, and here brutal hand-to-hand fighting broke out.

Exhausted as they were, the Australians fought on. When their ammunition was gone, they used their bayonets and guns as clubs. When the guns were broken or lost, they used their fists and helmets. Savage, bitter men tore at each other’s bodies with whatever tool came to hand. Modern warfare devolved into the tribal warfare of something far older, when strength of arm and ferociousness of the soul was a necessity for survival.

Men covered with so much grime they were unrecognisable to each other fought on and on until a stray bullet hit an unexploded, half-buried artillery shell. The subsequent detonation cleared a large section of the trench and buried Ash and his men.

Pressed hard by the German advance, the surviving Australians began withdrawing into the few surviving strongpoints, and though they were still fighting, they were desperately outnumbered and outgunned. Worse, what few messages they sent to their own lines were either ignored or disbelieved. As far as Allied command was concerned, if there was an Allied attack going on in the Armentières region, it was an unofficial one and everyone involved was on their own. They ordered no more supplies or reserves to move forward, leaving the desperate and increasingly outraged Australians to hold until the decision could be reversed.

By the time they’d dug themselves out once more, Ash and his men were now behind the enemy line, which had pushed well into the Pinchgut complex. Creeping through what was left of their trench for a quick inspection, Red slunk his way over to Ash and asked, ‘What we gonna do, Sarge?’

Taking a deep breath as though he was about to dive underwater, Ash slid back into the collapsed trench and fished out a Lewis gun and a few of the round-shaped magazines the weapon needed. Since first receiving these hand-held machine guns, the Australians had become highly adept at their use, carrying and firing them from the hip as they charged rather than laying prone and setting them up on their almost useless stand—indeed this was often removed for the sake of weight.

Hefting the large weapon over his shoulder and climbing out of the hole, Ash passed the gun to the men for inspection to ensure it was in working order.

Getting a thumbs-up, Ash winked at his squad. ‘I don’t know about you boys, but I’m getting back into this fight. I need to ask a very hard question to a German over there.’

The survivors nodded in agreement, grabbed what weapons they could, then on Ash’s signal hauled themselves out of the trench and began duck-walking toward what was left of the fortress.

After two hours of non-stop fighting, the diminishing Australians left in the trenches began backing around the last bend before the base of Pinchgut. The large concrete bunker was now the final section still controlled by the Diggers, who were determined to make it cost the enemy more than it was worth. With their hand grenades gone and their Lewis guns empty, all these men were left with were a few pistols and the odd rifle. The Germans advanced, firing and lobbing the occasional stick grenade as they methodically crept forward.

The Australians were all but done when the Germans suddenly lost focus on their attack. A number turned and began firing back the way they had come.

One overly ambitious Digger popped his head around Pinchgut’s ruined wall before slipping back with a huge grin covering his muddy face.

‘You lads aren’t going to believe this.’

Firing from the hip, Ash laid down a withering barrage of Lewis-gun fire while his squad grabbed German guns and hand grenades from the bodies about them. Though outnumbered, the surprise attack from the direction of their own lines caught the Germans off-guard and a wave of panic rushed through them. A few snapped back wildly inaccurate shots at the charging Australians, while most tried to blindly run back down the hill toward their own distant trenches—right where Ash and his men were holding out.

Not everything was going the way of the Allies. Pockets of Germans held their nerves, and thanks to the orders of experienced officers it looked like they were just about to regain control when help for Ash and his men arrived from the Diggers left in Pinchgut.

Together the remnants of the Allied attack managed to force the Germans into a retreat, and they re-joined inside the ruined Pinchgut bunker. Before they could make a decision on what to do next, officers blew their recall whistles and the Australians began staggering back to their original trenches. They arrived just as a new barrage dropped from the heavens, ensuring the section could not be taken by the enemy. Anyone caught in the open paid the price, as did those unlucky enough to be in a foxhole that took a direct hit. Australian soldiers were once again buried alive, their irretrievable bodies left to nourish the blood-drenched fields of Western Europe.

Two days after it began, the battle was over. The Allies moved enough support into the area to take the pressure off Armentières, ensuring the section could not be taken by the enemy. The Germans had a growing list of problems in other regions that required their attention, so could not continue their counterattacks, and so the entire section of the front fell quiet once more.

In a war known for its butchery, the Australian 1st Division had suffered more than its fair share at Pinchgut, and now they were to discover that the unofficial battle was being ignored by High Command. Any personal achievements of the men were being dismissed, though fresh reserves were finally ordered forward to replace the ragged, shattered soldiers who had just achieved the almost impossible.

These men, covered head-to-toe in mud and blood, began staggering back toward the relief area behind the trenches. Ash marched beside his motley army, along with only three survivors from his squad. The rest had either been buried in the shelling or had fallen during the German counterattack.

Due to the unit’s catastrophic losses, once they arrived back at headquarters there was talk the entire brigade was likely to be disbanded, but the death stares from the survivors made it clear that was never going to happen. Recruits would be found, the injured would heal and return, and the division would continue on.

Making the long trek back to a staging depot to rearm and scrounge some fresh uniforms, Ash and his men passed lines of fresh-faced soldiers in clean uniforms from various Allied countries, many of whom were looking at the Australians with a mixture of awe and horror. Red grinned and announced, ‘Enjoy the game, lads. The Germans are playing rough today.’

The youngest of the survivors was a replacement called Smith, sent to the unit after Gallipoli. His paperwork said eighteen, but most of the men believed he was far younger than that. As the group trudged past a gaggle of soldiers, Smith tapped Ash on the shoulder and asked, ‘What the fuck is that, Sarge?’

Bypassed by the columns of men moving to the front, as though he was a leper, was a soldier tied to a wagon wheel. About him stood a growing collection of returned soldiers from the front, their grim faces matching their torn and dirty uniforms.

The man was alert and clearly in pain as his feet only just touched the ground to support his weight. As tired as they were, the sheer absurdness of the situation forced the men to investigate.

‘What’s all this?’ a trooper called Touhy asked the soldier on the wheel.

‘You haven’t heard?’ a voice from the crowd said incredulously. ‘Last night a squad went on patrol into no man’s land and found one of our boys crucified to a tree.’

‘It was a church door, and they used bayonets to pin him in place,’ a Canadian soldier explained.

‘Jaysus,’ Touhy spat.

‘Yeah, and now some officer has crucified this Tommy here.’

A British lieutenant heel-and-toed through the corridor between piles of ammunition boxes and food stores and parted the gathered crowd. He pulled to a halt in front of the man on the wheel and proudly boasted, ‘Not crucified. Field Punishment #1, I will have you know. Now, I would ask you to not converse with this man.’

‘Punishment? For what?’ Red asked the young officer in his ludicrously clean uniform.

‘I hadn’t cleaned my boots before inspection,’ the soldier answered in a thick, Yorkshire accent. “Captain ’arwood ordered I do this for two hours a day for the next week and a half as “penance”.’

Touhy looked incredulously at the ruined landscape about them. ‘They crucified you for having dirty shoes in this hell hole?’

‘It could be worse,’ the lieutenant said, about to move on. ‘I’ve seen some of those conscientious objector fellows placed on the wheel for three months.’ He then spun about and marched back the way he had come.

Having just faced down what felt like the whole German army, the absurdity of the situation took hold of Ash and, before anyone could stop him, he unsheathed his bayonet and cut the man down from the wheel. Instantly, the soldier slumped forward, moaning as blood painfully rushed back into his extremities. The Diggers caught the prisoner before he fell and lowered him gently to the ground. They began rubbing and slapping his hands and feet to help kick-start the circulation back into his limbs again.

‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’ the lieutenant cried, running back to the wheel.

Ash stood up and faced the officer, who nervously stepped in, nose to nose, and snarled, ‘How dare you? What’s your name, man? I’m having you arrested for …’

‘You’re not arresting anyone,’ Ash said coldly, pushing the younger man away with one hand and leaving a dirty print on the man’s pristine uniform. ‘Isn’t this place bad enough without doing this crap to our own? And on today of all days …’

‘No one found a crucified soldier,’ the officer said with a condescending smirk. ‘The Germans wouldn’t be that stupid.’

Something in Ash snapped. Friends he had served alongside for three years now lay rotting in the ruins of a French town, and amid this brutality now he was learning both sides were crucifying each other. He grabbed the officer by his shirt front, spun him in place, and forced him to look at the man crucified to the wagon wheel as an answer to the sorts of brutalities a stupid person could inflect.

The lieutenant did not take kindly to being manhandled in such a way and he clumsily pulled himself free, then threw a right fist at Ash’s jaw. A blind man could have seen the punch coming, and Ash managed to twist his head, turning what could have been a disabling blow into a glancing hit. As the lieutenant stepped in to follow up with another punch, Ash lifted his right arm to block the blow, then fired off an uppercut of his own. The punch caught his opponent squarely on the chin and sent him tumbling backward into the dirt.

Blinding rage at the punishment for such a minor infringement welled up inside Ash. Ghostly images of the faces of his lost friends superimposed themselves over the pained expression on the crucified soldier. Though he could never get justice for the friends he had just lost or for the man who had been crucified, right now he could get his hands on the next best thing, the evil bastard who had enforced the punishment of the soldier tied to the wheel.

Ash watched as the lieutenant got up from the ground. Before he could throttle the buffoon, however, a swarm of MPs arrived and threw themselves on the sergeant, tackling him to the ground with the sheer weight of their numbers.

Chapter Three

General Headquarters, Montreuil-sur-Mer

The large dining hall in the chateau, which General Douglas Haig had taken over as his personal quarters, had become something of a morning meeting room to his staff. Officers from the various war departments would gather there before their commander took his breakfast and pass on any urgent news they had received throughout the night, along with any rumours and titbits they had uncovered. It was not only the common soldiers who suffered from gossip.

Once they were all caught up, Haig would pass on any new orders or questions he had, and the men would head back to their departments to get on with their day. All would then reconvene at GHQ for their afternoon orders and strategy sessions.

This day the dining room was bursting with officers, not only from the British army but several of the other nations fighting alongside them on the Western Front. Though countries like New Zealand, Canada, and Australia had their own general staff, as citizens of the Commonwealth they fell under the authority of the British commander.

All stood to attention when Haig, his moustached face the very picture of the recruitment posters hanging across most of the British Empire, entered the room.

Sitting at the head of the large table, with his chief of staff by his right and his personal secretary—already taking down notes—on his left, Haig gave a nod and the morning conference began. News of German infiltrations and Allied night raids were first reported, followed by provision numbers and supply issues. Only when every conceivable problem and troop deployment had been passed on did Haig bother to ask about the condition of the half-million men directly under his command.

Instantly a dozen hands shot up, asking permission to speak on the matter. One by one, the officers from the numerous divisions that made up the Allied force gave accounts of the conditions the men they represented were facing. Most began explaining the physical and mental condition of their troops, then the numbers of wounded and killed, then finishing up with any court-martials that had been instigated.

The war seemed to be going well, yet the buoyant mood of the room changed when a colonel from one of the Canadian divisions took a large step away from the table, so he could be seen, and then in a clear voice began his report.

‘We are having real trouble with the 15th battalion and the 48th Ontario Highlanders. It would seem a patrol entered no man’s land last night and discovered a soldier executed by the Germans near what remained of a small farmhouse.’

‘Terrible news, Colonel,’ Haig’s chief of staff said, ‘but sadly nothing newsworthy. Why has this got the men upset?’

‘It was the manner in which this man was executed, sir,’ the colonel answered. ‘The rumour is the Germans nailed him to the barn door with bayonets. They crucified him, sir.’

At the word ‘crucified’, several officers in the room yet to make their reports began adding their voices to the claim. In a war renowned for its horrors and lack of humanity, it seemed that during the night the Germans had stepped up the psychological element of the conflict by crucifying several soldiers from the various nations opposing them. These bodies were left for the Allies to discover in no man’s land.

Many officers reported some units were already refusing to move forward, and others were calling for an immediate attack to take revenge on those who had perpetrated the crime. Soldiers, well used to blood on the battlefield, who had killed in the most brutal and primeval ways imaginable, were seeing this act as something far worse. To them, this was a crime, and they were crying out for justice.

Haig looked at his two closest confidants sitting next to him. The nervous looks they returned told him things could get very ugly if they did not move fast. Was this an underhanded way to dishearten the Allied army, or some sort of trap, perhaps to trigger a massed charge forward by outraged soldiers into the teeth of German guns? If they were not vigilant, then the carefully crafted Allied front, meshing units from nations across the globe, was about to collapse.

How did one stop half a million men from charging forward two hundred feet to take vengeance on those they had now demonised? Worse, how did one stop all those soldiers from unifying behind a single cause, and perhaps bring something of a democracy to the Western Front? What if the men began calling for this matter to be resolved before they would follow any further orders?

Haig and his confidants had been contemplating such possibilities for months as rumours of mutiny and mass sedition began to spread amongst the men. Because of this, they immediately realised this crucified soldier situation could turn into something dangerous if it was not suppressed. As the officers around the table argued amongst themselves about what could be done, Douglas Haig began not for the first time, to contemplate how he was going to save the war.

Chapter Four

With the dining hall cleared of most of the junior officers, the British High Command’s inner circle sat down to confer on what had been happening within their front lines. Many of the departed officers had been visibly upset at what had been discussed, and it had taken General Haig to stand and glare everyone into submission to complete the earlier meeting.

After sorting through the various reports, it became obvious things were not quite as bad as had been initially argued. Instead of a series of brutal crucifixions, to Haig it seemed there had only been a few, or perhaps even just one. Officers from the Indian, South African, and New Zealand regiments agreed their reports were more about the rumour of soldiers being crucified than any confirmation their troops had physically encountered them.

As the English and Canadians were so enmeshed on the front, it was impossible to determine which nation had made the initial report to allow HQ to trace the source of the rumour. The Canadians had been adamant it was one of their men who’d been murdered and, normally so stoic and dependable, their reaction was a worrying occurrence. They were calling for answers and HQ to do something about the crime.

On top of this, intelligence had arrived that the French army—always one bad word away from mutiny—were already talking about pulling troops out of the line to try to restore discipline. Many junior French officers were as outraged at the crime as their men and were proving to be extremely ‘French’ about the entire affair. Their report this morning was that, though they wanted revenge for the crucifixion, their men—after facing years of unspeakable horror in the trenches—seemed to have lost their nerve for the fight. It just didn’t matter to them if it had been French soldiers who’d been crucified or not, the entire population of France was feeling as though they’d already been nailed onto the cross. The French nation was fatigued and looking shaky, and this latest outrage just seemed to increase their distaste for the war.

And then there were the damn Australians.

Renowned for being the most ill-disciplined soldiers in the Allied lines, it was unclear if the Australians had found one of their own crucified or had just taken umbrage at the fate of an Allied soldier. It wouldn’t matter as, either way, they were already calling for blood, and if those troublemakers weren’t silenced soon, their own brand of soldiering could very quickly spread to the other troops stationed around them.

It was clear to Haig that this situation had to be dealt with before it got out of hand, and though never one to ask for advice, the general tabled the question to the men before him.

‘What do we do?’

‘Come down hard on the men,’ one of the traditionalists at the table called out. ‘Discipline, either earned or imposed, is the only way to end this. Take a man from each of the most mutinous units and punish them.’

‘Shoot a few, especially from the colonial ranks, and the rest will settle down,’ another British officer added.

General Albert Mackenzie was the only Australian in the room. He stood up at this proposal and reminded those present of the hard line his government had taken on just such actions.

‘You shoot a single Australian over such rubbish and you will most certainly have a mutiny on your hands.’ Most of those seated around the table rolled their eyes at this bothersome fact. ‘Actually, forget that,’ Mackenzie continued. ‘You shoot one of our men over this and you won’t have a mutiny, you’ll have a second front. I’m not sure how many times we have to tell you galahs, but we simply won’t be made the scapegoat for your idiocy.’ Mackenzie sat back down, then added, ‘Again!’

‘General Mackenzie,’ Haig said with a calm, dangerous tone, ‘we are all well aware of your nation’s stance, especially as you mention it every time we ask you to do anything.’

‘History has taught us what happens when we blindly follow England … sir,’ Mackenzie replied, not disguising the contempt he had for what had occurred between the two nations in the past. ‘We won’t be repeating that mistake, so you’ll excuse me if I remind you again since you seem intent on proving you didn’t listen the first time!’

The losses the Australians had suffered at Gallipoli, stacked on what had occurred in conflicts such as the Boer War, had left a distinct divide between Empire and subject. Things had not improved once the Australians arrived in Europe, and they had proven themselves an invaluable tool in the Allied effort to defeat Germany.

‘If I may?’ asked an officer from beyond the orbit of the great table.

As all heads turned, this officer, who had been quietly seated in one of the room’s comfortable chairs, stood, straightened his well-pressed uniform, then stepped up to the table.

‘I believe we are looking at this the wrong way.’

One of the many staff officers standing about the room leaned in and whispered in Haig’s ear, ‘Captain Fitzhugh. He’s the officer from Military Intelligence I’ve been warning … err … telling you about, sir.’

Haig motioned for the officer to continue. ‘You have something to add to all this, Captain Fitzhugh?’

‘I do indeed, sir.’ If it were not for his uniform, Captain Simon Fitzhugh would have looked as though he was waiting for a train. Calm and casual, his officer’s cap sitting at a slight, unregulated angle, his intelligent blue eyes seemed to blaze with a mischievousness that certain university-bred students were renowned for. Not terribly tall, nor that well-built, the captain had the air of a scholarly man rather than a soldier, a look that held him in contempt with the more traditional segments of the senior service. His current rank, however, did not reflect his abilities. He was a good field officer who had suffered demotions due to his manner with his superiors. As fast as he earned promotions, he lost them, leaving Fitzhugh in a strange limbo at the rank of captain. Deserving of more, but incapable of maintaining it.

‘I believe we may be going at this the wrong way, sir!’ the captain repeated, adding the ‘sir’ as evidence he could play the game. Almost as an afterthought, he added, ‘To suppress a rumour is impossible, especially one as gruesome and nasty as this. All you will do is fire more rumours and likely something even worse.’

‘Worse?’ Haig asked.

‘Yes, sir. Suppression will lead to conspiracy theories amongst soldiers with time on their hands, who now have little to think about but why their commanders suppressed the news of a crucified soldier. Not only will they resent you even more, they will question the motives of everything you ask of them from this point on.’

The looks of the men at the table informed Haig that Fitzhugh’s idea had not gone over well.

‘The men don’t seem to mind being the sacrificial lambs in this war, sir,’ Fitzhugh went on, ‘but it’s probably best not to remind them too much about the fact that’s what they are. They might take exception to the idea.’

General Roberts, a man who lived behind a face that permanently scowled at the world, leaned back from the table and craned his head around to gauge the reaction of the other officers seated with him.