3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Globetrotter Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

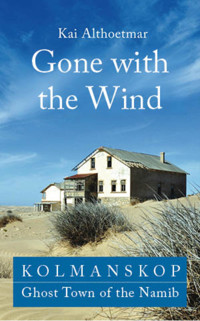

Kolmanskop, the former German diamond mining settlement in South West Africa, now Namibia, is a ghost town and museum. During the final phase of the German Empire, the place was full of life, an outpost of the German way of life in Africa - Kaiser Wilhelm's dream of a German Kimberley. The meteoric rise began in 1908 when a railway worker found the first diamond in the desert sand. The small town in the Namib Desert became the richest town in Africa. In the bars, people paid in carats, the beer came packed in straw sleeves on ‘Woermann’ steamers from the German Reich, after work they did gymnastics and bowled in the hall, on Sundays they went antelope hunting and the pastor came by motorbike. Then came the decline... Kai Althoetmar went in search of traces in Kolmanskop. - Illustrated eBook with numerous photos.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Gone with the Wind

Kai Althoetmar

Gone with the Wind

Kolmanskop. Ghost Town of the Namib

Imprint:

Title of the book: Gone with the Wind. Kolmanskop. Ghost Town of the Namib.

Year of publication: 2025.

Publisher:

Globetrotter Publishing

Kai Althoetmar

Am Heiden Weyher 2

53902 Bad Muenstereifel

Germany

Althoetmar[at]aol.com

Text: © Kai Althoetmar.

Cover photo: Kolmanskop, Namibia. Photo: Eric Bauer, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The research for this book was self-financed and without grants or benefits from third parties.

Kolmanskop, aerial image. Photo: Sky Pixels, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Gone with the Wind

Kolmanskop. Diamond Ghost Town of the Namib

A fierce wind sweeps from the Atlantic through the Namib Desert towards the diamond Sperrgebiet. Fine sand seeps through the windows and cracks in the doors of the wild west-style colonist houses of Kolmanskop. Metres of sand pile up in the parlours and floorboards. Glaring sunlight streams through the windows, whose weathered shutters hang crookedly from their hinges. Nobody lives here any more. Except perhaps a few geckos and scorpions.

A group of tourists trudges after a young German-speaking guide. A visit to a restored showroom. ‘And here you can see how a German diamond digger lived back then.’ Cot, chest of drawers, chamber pot, dinner service, Kaiser Wilhelm in oil - the romance of a doll's house in South West Africa. ‘Please follow me to the gymnasium!’ This has also been preserved: The horizontal bar, pommel horse and parallel bars look as if soldiers of the imperial Schutztruppe had just done pull-ups to prepare for the next Herero uprising. On Kaiser's bowling alley, everyone can have a go.

Colonial map from 1905.

Kolmanskop, the former German diamond mining settlement in South West Africa, now Namibia, is a ghost town and open air museum. During the final phase of the German Empire, the place was full of life, an outpost of the German way of life in Africa. Kaiser Wilhelm's dream of a German Kimberley.

At the turn of the century, Europe was in the grip of colonial fever. Germany had its sights set on South West Africa. The Bremen merchant Adolf Lüderitz was in the service of His Majesty and his own mercantile interests. In 1883, he moored his brig in the bay of Angra Pequena, today's Lüderitz. His confidant Heinrich Vogelsang talked the Nama chief Joseph Fredericks out of the land within a five-mile radius of the bay. The price: 10,000 Reichsmarks and 260 rifles.

Colonist's room. Photo: Tee La Rosa, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Further land purchases followed. The German Southwest Chronicle began with a big rip-off: Adolf Lüderitz estimated each mile at 7.4 kilometres instead of the English measurement of 1.6 kilometres. One year later, in 1884, the Berlin Conference: the whole of South West Africa became a German protectorate. German settlers immigrated in the hope of farmland and a better life.

The settlers demanded protection. The young Kaiser Wilhelm II sent the Schutztruppe. The first twenty-one colonial soldiers went ashore in 1889. By 1915, the end of the German colonial era in South West Africa, much blood was still to seep into the desert sands. The Schutztruppe relentlessly crushed uprisings by Nama and Herero people.

The colonial rulers opened up the country by building a railway. The railway line from Lüderitzbucht to Keetmanshoop was completed in 1908. The Thuringian railway official August Stauch inspected the 25-kilometre stretch of track between Lüderitzbucht and Grasplatz station, which was frequently blown away by the shifting sands of the Namib. Blacks had to shovel the tracks clear. Stauch instructed his men to look out for unusual-looking stones. Stauch's hobby was mineralogy. On 14 April 1908, the worker Zacharias Lewala came to Stauch with a find.

Lewala came from the Cape Province and had worked in the Kimberley diamond mine in South Africa. Stauch tried to scratch the glass of his pocket watch with the stone. He succeeded, the stone was harder than glass: a diamond! At first, railway foreman Stauch kept the find a secret, bought the mining rights for the site with friends in the know and staked out claims. Hired blacks and half-breeds were chased through the sand, guarded by overseers with whips and pistols, in search of more nuggets.

By the end of 1908, 39,000 carats of rough diamonds had been unearthed. Stauch became the diamond king of German Southwest Africa. Hundreds, then thousands of fortune hunters set off. Word of the small miners' good fortune soon reached the Reichskolonialamt, the Imperial Colonial Office. The imperial government put an abrupt end to the hustle and bustle. As early as 22 September 1908, it declared a 100-kilometre-wide coastal strip from the 26th parallel to the South African border a diamond restricted area. The area was placed under the control of the quickly founded Deutsche Diamanten Gesellschaft, the German Diamond Company. It employed its own people: German craftsmen and engineers, black contract labourers.

The soldiers of fortune had played their hand. From then on, the empire made money. The diamond company had the mining town of Kolmanskop built in the desert, 15 kilometres from Lüderitzbucht, named after the Nama Johnny Coleman, who got stuck here in the wasteland with his ox cart in 1905. In 1910, the town was already a booming desert oasis and the per capita income of the small town was the highest in Africa. By 1914, 1,000 kilos of diamonds had been mined.

The German Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia could have bathed in carats in Kolmanskop if the shots fired in Sarajevo had not put a spanner in the works of his planned trip to Deutsch-Südwestafrika in 1914.