3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Edition Zeitpunkte

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

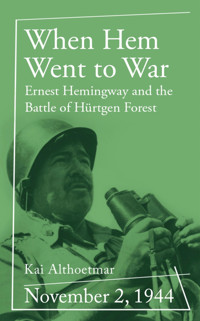

In November 1944, the U.S. Army experienced its bitterest fiasco in the war against Germany at the Battle at the Hürtgen Forest. Since the landing in Normandy, the famous American writer Ernest Hemingway accompanied the infantry as a hard-drinking and intrepid war correspondent and travelled from front to front. He wrote reports for Collier’s magazine and collected material for a novel, but repeatedly became an actor in the war himself, later boasting about the killing of countless German soldiers. He led Resistance fighters outside Paris, stockpiled weapons in the Ritz Hotel, turned a farmhouse in the German Snow Eifel into an artists‘ meeting place. In the Hürtgen Forest, however, the author fell silent in the face of the horrors of war. The book describes Hemingway’s novelistic experiences during the war in the West in 1944/45 and his controversial role as a war reporter against the backdrop of the heavy fighting in Normandy, the Snow Eifel and the Hürtgen Forest. The author has followed Hemingway's footsteps into the villages of the Southern Eifel and the Hürtgen Forest and lets numerous contemporary witnesses share their war memories. He also explains for the first time what the "Hemingstein Castle" in the Eifel village of Schweiler was all about. – Ebook with numerous photos and maps.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Inhaltsverzeichnis

When Hem Went to War

Kai Althoetmar

When Hem Went to War

November 2, 1944. Ernest Hemingway and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest

Imprint:

Title: When Hem Went to War. November 2, 1944. Ernest Hemingway and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.

Year of publication: 2025.

Publisher:

Edition Zeitpunkte

Kai Althoetmar

Am Heiden Weyher 2

53902 Bad Muenstereifel

Germany

e-mail: Althoetmar[at]aol.com

Text: © Kai Althoetmar.

Cover photo: Ernest Hemingway, 1944. Photo: unknown photographer, JFK Presidential Library.

The research for this book was self-financed and without third-party funding.

Chapter 1: From Normandy to the southern Eifel

Apples, pumpkins and potatoes from the Thanksgiving service are still lying in front of the altar. The ceiling lights are set in modern glass spheres and the colourful stained glass windows show abstract motifs. The Catholic parish church of St Joseph in Vossenack, Rureifel, is no longer the one from 1870, which no longer exists. It is the one from 1953. Votive plaques hang in the vestibule next to a statue of the Virgin Mary. ‘Mary has helped’. That was September 1955. ‘Thank you for visible protection!’ Easter 1961. ‘Mary always helps.’ October 1968. ‘Thanks for rescue from mortal danger’ - on 30 March 1970. 1982: ‘Mary never leaves us’ - except in November 1944, when Mary didn't help either.

In the late autumn of 1944, the church became a theatre of war. The ‘All Souls' Day Battle’ in the Hürtgen Forest, 6 November 1944, day five of the battle: the German attack from the Tiefenbach Valley, the ‘Death Valley’, just a few kilometres away, had only come to a halt in Vossenack. Two US companies had fled from the Germans in panic. Control of the town had previously changed hands between the Americans and Germans twenty-eight times. Young GIs are said to have entrenched themselves in the church and fired down from the organ loft, while the Germans returned fire from the sacristy.1

Vossenack, municipality of Hürtgenwald, district of Düren, population 2,259. If you drive through the street village today, you will find everything normal: the brick houses, two butchers, post office and savings bank, village pub and the ‘haircut shop for men’. It is the beginning of October 2014. The Italian restaurant is advertising porcini mushrooms with the pasta, and every Monday the grilled chicken man stops in front of the church. Everything is as usual. Only one thing stands out. Nothing in the village is old. Just post-war architecture everywhere. Only the retort housing estates with which the lignite company Rheinbraun compensates for villages that have been dug up look like this—except that the excavator front runs 60 kilometres to the north.

The parish church in Vossenack. Photo: Kai Althoetmar.

One person who witnessed the fighting in the Hürtgen Forest was the American author Ernest Hemingway. Since the Normandy landings in June 1944, the later winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature had accompanied the U.S. Army during the war in the West. As a war correspondent, he wrote reports for the renowned US weekly magazine Collier's about D-Day, the liberation of Paris and the trench warfare in the southern Eifel. However, Hemingway's war adventure had actually begun much earlier: when the USA entered the war in 1941.

Flashback. September 1941: German troops have invaded the Soviet Union and were already fighting outside Kiev. The Americans— officially still neutral—were supplying Great Britain, the Soviet Union and China by sea with essential war material and have occupied Greenland and Iceland. The German war leadership was expecting the USA to enter the war soon. On 4 September 1941, the American destroyer USS Greer informed a British bomber of the position of the surfaced German submarine U-652. The British aircraft dropped depth charges. The German submarine commander believed he was under attack from the USS Greer and attacked the destroyer with torpedoes. From then on, the Americans attacked all Axis ships they saw in the sea neutrality zone. The U.S. Navy waged an undeclared naval war against the German Reich, Italy and Japan. On 6 November 1941, the Americans captured a German freighter disguised as a US merchant ship, the Odenwald, in the South Atlantic. Berlin and Rome reacted. On 11 December 1941, four days after the attack by Japanese naval aircraft on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the German Reich and Italy declared war on the USA.

For Ernest Hemingway, who had lived in Cuba with his third wife Martha Gellhorn since 1939, it was also the signal to throw himself into the fray. Hemingway knew the war from his own experience: at the age of eighteen, he had been a volunteer Red Cross ambulance driver on the Italian side of the Isonzo front in Veneto during the First World War and had seriously been wounded by Austrian shrapnel on 8 July 1918 while handing out chocolate and cigarettes to soldiers in the front line. Despite his injury, he pulled a wounded Italian out of the line of battle. However, he was hit by machine gun bullets. Later, as a reporter, he covered the Greek-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922, the occupation of the Ruhr in the German Reich in 1923 and the Spanish Civil War that had broken out in 1936, before travelling to Japanese-occupied China with Gellhorn as a pair of correspondents in 1941.

In Cuba, the couple lived on the finca La Vigía in San Francisco de Paula, south-east of Havana. Since 1934, Hemingway's property had also included the twelve-metre-long sailing boat Pilar, which he was taking on trips to the Caribbean. After his return from China, it was to become a ‘warship’. As in Spain, the supposedly apolitical novelist Hemingway felt called to fight against fascism. ‘He wanted to experience his war at sea, in the air and on the battlefields as an adventurer who voluntarily takes risks, as a condottiere of another time,’ writes Hemingway biographer Georges-Albert Astre. In 1942, Hemingway offered his services to the US ambassador to Cuba, Spruille Braden, and was integrated into Naval Intelligence.

The Pilar was transformed into a submarine trap. ‘The boat was equipped with heavy machine guns, bazookas and depth charges and was tasked with giving the appearance of a peaceful yacht, allowing itself to be stopped by an enemy boat, seizing it and sinking with it if necessary,’ writes Astre.2 Hemingway was the commander of the nine-man crew. For two years, he sailed and cruised through the straits of the Keys off the Cuban coast, always on the lookout for German submarines - which were actually travelling in US waters and also in the Caribbean. But: no German submarine appeared in front of Hemingway's enemy reconnaissance yacht. Everything that the illustrious leisure captain observed in terms of anomalies ended up with the naval defence. When the naval attaché himself patrolled Hemingway's waters in 1943 and located German submarines there, he ordered the author and his crew back. The next day, a German submarine did indeed appear. Ambassador Braden later judged: ‘Ernest's services were so valuable that I strongly recommended him for an honour.’3

In May 1944, Hemingway decided to take part in the invasion of Europe and to report on it for Collier's—thus viciously driving out his wife Martha, nine years his junior, who had been writing about the war for the magazine. The marriage was at an end, and the strongman with a penchant for hunting, boxing and bullfighting was also suffering from impotence. Hemingway, then forty-four, had long been world-famous thanks to novels such as ‘The Sun Also Rises’ and ‘A Farewell to Arms’. ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman as fighters for the Spanish Republic, was just showing at the cinema.

At first, ‘Papa’, Hemingway's pet name, wanted to join General George S. Patton's armoured divisions of the 3rd US Army in Normandy. ‘Tank warfare, however, proved too confusing for him, and he took up instead with the Fourth Infantry Division of the First Army’,writes Kenneth S. Lynn, Hemingway biographer and long-time professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.4 However, if his letter to the Russian war reporter and writer Konstantin Simonov, dated 20 June 1946, is to be believed, Hemingway would have preferred to serve on the Eastern Front. ‘All through the war I wanted to be with the army of the U.S.S.R. and see that wonderful fight, but I did not feel justified to try to be a war correspondent there since A-I did not speak Russian and B-because I thought I could be more useful in trying to destroy the Krauts (what we call the Germans) in other work.’5

In Great Britain, Hemingway prepared for the invasion - sometimes on the airfield and in the air, sometimes drinking in a hotel. As an inquisitive reporter, so the story goes, he flew on R.A.F. reconnaissance flights and bomber missions and wrote for Collier's about how the Royal Air Force pilots tried to intercept German V-missiles. During a visit to the editorial office of Time magazine, he met the US war reporter Mary Welsh, who was to become his fourth and last wife in 1946.

Hemingway's war reporter's pass, issued on 20 May 1944. The 110-kilo author is given the military rank of Captain.

Shortly before 6 June 1944, the day of decision and debarkment, Hemingway had a car accident in London. ‘Wearing a bandage to protect his head wound and limping perceptibly from the swelling in his knees, Hemingway forced himself to board the attack transport Dorothea L. Dix on the night before D-Day’, reports Lynn.6 However, Hemingway did not go ashore. In his book ‘Ernest Hemingway und der Krieg im Westen 1944/45’ (’Papa Goes to War. Ernest Hemingway in Europe 1944-45’), the British military historian Charles Whiting pokes fun: Hemingway was ‘in the sixth wave of ships that had anchored far from shore out of firing range.’7

In his Collier's report ‘Voyage to Victory’, it reads quite differently. Hemingway, the frontline fighter, the D-Day hero. It was June 6, 1944. Fox Green coastal section, Omaha Beach, was the longest section of the Allied landing. ‘As we moved in towards land in the gray early light, the 36-foot-coffin-shaped steel boats took solid green sheets of water that fell on the helmeted heads of the troops packed shoulder to shoulder in the stiff, awkward, uncomfortable, lonely companionship of men going to the battle.’ The transport barge drifted off the coast. Mines lurked in front of the surf, ‘contact mines […] that looked like large double pie plates fastened face to face’. Metal beams, wooden logs and poles raised in the air, the dreaded ‘Rommel's asparagus’, rutted the water. ‘We were in the range of the antitank gun that had fired on us before’, he wrote, ‘and all the time we were maneuvering and working in the stakes. I was waiting for it to fire.’

Hemingway describes the German snipers on the beach and anti-tank guns: ‘The Germans were still shooting with their antitank guns, shifting them around in the valley, holding their fire until they had a target they wanted. Their mortars were still laying a plunging fire along the beaches.’ Towards the end, it says: ‘All that were lost were lost by enemy action. And we had taken the beach.‘“8

Landing in Normandy. Fox Green sector, Omaha Beach, 6 June 1944. Photo: Robert F. Sargent, National Archives and Records.

Hemingway's brother Leicester later spread the legend that the star author had fought on Omaha Beach on 6 June 1944. For Kenneth S. Lynn, who died in 2001, the story of ‘Hemingway's Longest Day’ was pure fairy tale. Lynn alludes to the D-Day report ‘The Longest Day’ by US author Cornelius Ryan, whose screen version made film history. Lynn: ‘World War II, it was clear, was going to be another vehicle for the Hemingway myth […].’ As was the case after the First World War, ‘even the tallest of the tales that Hemingway dreamed up would be eagerly disseminated by ingenuous admirers’, Lynn writes in the biography ‘Hemingway’.9

Hemingway as a civilian. Photo: Florida Keys-Public Libraries.

In 1987, German filmmaker Bernhard Sinkel made a four-part TV series about the life of the Nobel Prize winner with Stacy Keach as Ernest Hemingway. The four-part series shows ‘Papa’ as a macho man: open shirt, binoculars around his neck, his helmet strap loose, a Jack of all trades who commands a bunch of Resistance partisans during the liberation of France, spies on the German positions, flirts with Mary Welsh and never misses a drink—but has little to do with war reporting.

But Hemingway was no coward in 1944/45. He consistently lived up to the idea he had of himself of being a ‘hero from another age’ and the maxim of despising death. Biographer Lynn reports how he crushed his kidney outside Paris when he ran into a German anti-tank gun in his motorbike sidecar. After braking hard, he and war photographer Robert Capa landed in a ditch and remained there for two hours under constant fire. For a while, Hemingway saw everything twice, spoke with difficulty, was injured in the head - two days' rest was enough for him.10 The sidecar motorbike was damaged and had to be towed away. From then on, the impetuous reporter continued the war in a jeep.

Hemingway, who spoke fluent French, claimed to have taken the town of Rambouillet thirty kilometres from Paris with his partisans. Ernest's bedroom in the Hotel du Grand Veneur was the nerve centre of all operations, according to a report by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the intelligence service of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS).