Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Editorial Costa Rica

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Editorial Costa Rica Short Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

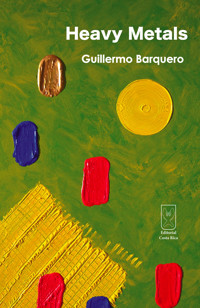

The construction of fantastic devices to evade the all-powerful hand of disease; the detour through the snowy roads of a cold and merciless Iceland; the fire of an inferno that burned down the misfortune of a world of blinded smokers; the force to the abyss through the recourse of a betrayal disguised as goodness. The ten short stories that compose Heavy Metals are pieces that have been torn from the anodyne of lives touched by boredom or physical ailments. In these stories, Barquero creates a narrative work in which the familiarity of things and trivial occurrences are subverted, as those beings who inhabit everyday scenarios undergo a savage change that has only been made possible by the touch of a demon or a word. They are bodies thicken by the weight of lead and mouths that taste like iron. Áncora Prize in Short Story 2010.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 149

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Guillermo Barquero

Heavy Metals

SHORT STORIES

Áncora Prize in Short Story 2010

EMPIRE OF FIREBREATHERS

For Christian Aguilar

His appearance was the same as usual but slightly paler. The only important thing about the room wasthe immaculate whiteness, perfectly medicinal. I shook his hand, and I thought I had touched a block of ice. We joked about the hospital’s coldness, the nurses’ deference or excessive bitterness, their white pants, and the underwear they wore. That first day I visited him, we didn’t talk much about his disease.

The same night, I was informed over the phone that the day before his admission, he had felt weak and almost dead. He paled, went into a laboratory, and asked for a blood test. Within two hours—they usually take a couple of days to deliver the results—the lab manager called him and told him she had seen something irregular in the blood smear under a microscope. He wasn’t alarmed by that oddity, so he waited several hours before going for the results.

When he arrived, an emergency hospital admission order had already been issued for him. He thought it was a joke or an exaggeration. He was admitted. As he told me over the phone, he had looked at himself in the room’s mirror when he had his clothes changed. He felt that he was suddenly 40 years older, that he was haggard, and that his skin had become a reptile’s hide. We didn’t talk about the disease itself, but about its possible seriousness, which neither of us called it uncertainty, but it really was.

The following day, I entered the white rooms of the hospital again. I got lost twice in a row—intricate corridors and wrong directions that were more bearable thanks to the coffee with milk from a coffee vending machine. Eventually, I got to the room where Gabriel was admitted, Masculine Oncology 2.

Some of the sick people were talking dispiritedly, whiles others, as I waited in an oncology room, were resting heavily and pallidly in line with the seriousness of the entrance sign.

Gabriel was reading The plague by Camus. “Leukemia,” he told me without showing any surprise. My face, I hope, was one of total impassivity. I asked him about what it was next—whether chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or none of the previous ones. I didn’t know more than that. Gabriel gave me several explanations he himself didn’t understand. He mentioned the names of two doctors, who had just been introduced to him and two hospital wings whose names I didn’t hear.

He leaned back until he reached the green metal handle of the bedside table, put the book away —I could see that a whole, small library had been brought to him —and took out a magazine with a glossy cover, which looked as if it had just been bought—The Art of Machines. His father, Don Gabriel, had brought it to him, so that he entertained himself with something lighter than books, which wouldn’t let him recover well as he had tried to explain to him.

“Yes, leukemia.” When I left the room, and within the following days, I read a couple of articles about leukemia, which didn’t allow me to define it as I wanted. It is a disease of many faces, all complex and so nuanced at the same time that it can’t be framed as one would do with kidney stones or blindness.

In blindness, the person doesn’t see. If it is partial, he sees a little, but there isn’t much to say if it is total, as he sees nothing at all whatever the causes. Leukemia is a multi-headed monster that undermines the patient’s cellular systems. White blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts are lowered. The patient suffers from symptoms related to these deficiencies. There is anemia, opportunistic infections, and excessive bleeding.

I imagined Gabriel bleeding from his nose in his bed while reading The Plague. He called me that second night. On the other side of the receiver, apart from his voice that seemed to come from a grave, nothing could be heard but the wind blowing or a tiny noise from the line. It was too late to be calling from a hospital. He had been allowed to use his cell phone. We talked about leukemia like two strangers referring to episodes in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

I told him the little I knew trying to explain what I had gotten from the articles, which hadn’t been much. He gave me his opinion, what he had heard from the doctors, and what he had read in a little booklet he was given when he was admitted. We agreed that neither of us knew much. What we were sure of, we agreed, was that his condition was serious, although neither of us would say it bluntly.

He told me he was having trouble falling asleep. A 12-year-old boy—he didn’t even notice his name, just his date of birth on the head of the bed—was moaning constantly in pain, saying that his kidneys were going to explode and that he was dying. When he closed his eyes, hushed lamentations flooded the silence of the room of Masculine Oncology 2.

I couldn’t visit him for five days. Work matters. We talked on the phone every night. We joked as we did in the olden days of school and high school. I forgot Gabriel was on the other side, with dying and very sick or hopeless people. He seemed to forget it by carelessness or simple deliberation. He claimed his condition wasn’t as bad as that of the rest. Well, some were better, but most were terminally ill and greenish beings. He said that again and again.

He read almost all the time. He had finished reading The Plague and was with something by Oé, which had him fascinated. He hadn’t started chemotherapy, yet. He didn’t know why, but he said that should be the acid test. “You finish chemo, and you’re saved,” he told me one night. We changed the subject several times avoiding uncomfortable, circular conversations that brought up the subject of the disease and the treatment, which was more deadly than the disease itself.

He asked me when I was coming. He talked about an article in the magazine The Art of Machines, which he read after eating and when he intended to rest his eyes from the unchanging landscape outside the window. He needed few things to entertain himself—several thin wires, a flattened piece of metal, and a magnet. I asked nothing. He just told me to buy him those things, and then we would talk about it.

When I entered the room again almost a week later, I was welcomed by the ghost of Gabriel, who was identical to the one of the first day of admission, but with a deeper gaze, intensely blue cheekbones, and perfectly adapted to the ambiance of someone with leukemia in an oncology room. We hugged. Something we almost never did. We joked as expected. The nurses walked pass from left to right in that corridor with three seats. We talked about the underwear they wore under their white pants.

He mentioned chemotherapy, and I referred to leukemia as a chronic and extraterrestrial malady. I had read a couple of other things that ended up confusing me. I brought him the things he had requested without asking any questions.

In the room, he showed me an article about the history of slot machines, from the old, noisy, and heavy mechanical models with little apples on the screen to the modern electronic equipment, which clumsily and robotically imitated the previous ones. A whole issue of The Art of Machines was dedicated to the slots. Gabriel explained nothing. He simply put the magazine and the bag I brought him, in a drawer of the shelves.

He had almost finished reading Oé’s book and would continue with Alcools by Apollinaire. He told me with no irony that he had no choice but to gorge himself on books. He wasn’t in a position to reject literary genres.

I would visit him all the days I could. I told him some days would be impossible for me, as there would be important matters at work. We talked two days later. He called me at eleven-thirty at night. Anyway, I was writing two letters on my computer, so he hadn’t woken me up or interrupted me.

He told me he sweated and had started the treatment or a preliminary phase to condition his body. I imagined him hairless and in the form of a big, bald, yellow, sickly egg. His voice didn’t sound sick, though. We talked about books, boredom, the moans of the 12-year-old boy, the nurses, and the fucking, thankless life.

I could visit him until six days later. I expected Gabriel to be ruined and vomiting blood. He managed to convince me to visit him though I told him I didn’t want to bother him. I found that Gabriel was intact, slightly paler, and with all his hair. He noticed my reaction and explained the hospital’s periods and delays. Also, he hadn’t experienced the treatment’s violent phase.

We sat on the bed in the room of Masculine Oncology 2. The medicinal and sedative smell of the rest of the building had pervaded. The 12-year-old boy played with a little, electronic device. He looked at me when I entered. I imagined his moans.

“This was simple before,” Gabriel told me as he took the magazine in his hands. It was crumpled and looked like an issue from 30 years ago. I asked him what was simple before. “Cheat at the slots, get all the bucks out, and make them breathe and puke,” Gabriel answered. He opened the furniture’s metal drawer that was next to his bed. He showed me a mechanism that looked like a grasshopper made of wire, which was menacing, white, and interspersed with the metal plate and the magnet. “This is what I asked you for,” he said. I shrugged.

“With something like this, the former cheaters got all the coins out of the machines,” he explained, “it is a simple mechanism of small pulleys raised by the wires.” He showed me the magazine article’s diagrams. “Interesting,” I said and thought. “Very interesting.” “They didn’t even have to pull the machine’s lever,” he said, “they did it to pretend sometimes.” “And Apollinaire?” I abruptly changed the subject. He read Zone and then, more out of curiosity than boredom, closed it and continued scanning the slot machine article.

He took out a rectangular sheet of paper from a notebook with a list of items I should bring him as soon as possible. Certainly, it had to do with the machines. We didn’t set any dates and only agreed to talk when possible.

Two or three days went by and…nothing. I imagined Gabriel being undergoing the chemotherapy’s violent phase. If there was a particularly violent one within such atrocity. I had read more medical articles and had found it all too sinister. I dreaded calling Gabriel and hearing a corpse talk, breathe, and lament his damn fate.

The phone rang, and I thought I was dreaming. No idea what time it was, but it was a cold early morning in the middle of February. Gabriel’s voice was unchanged. We didn’t even talk about how late it was. He told me he couldn’t sleep, not so much because of the moans of the 12-year-old boy, who had been somewhat quiet the last few days, but because of his internal ones. He felt his organs were going to explode.

He vomited several times a day, or had unbearable heaves, which were nauseating overturns of a body that felt as if it were filled with lead. He asked me about the items on the list. “Which list,” I told him. I was half sleep. “The one from the last time,” a Gabriel, who didn’t look like the one with the unbearable vomiting and heaves, said. I told him I had bought everything. I told a half lie. I had been unable to get an anti-reflective plastic sheet he had asked for. No big deal. I hung up. We agreed to see each other in the afternoon of the next day.

Gabriel was reading the magazine when I entered the room. I was greeted by two men, whom I barely remembered. The 12-year-old boy looked at me and looked like a little dog in the rain. Then I came across another Gabriel, who was wrinkled, 200 years old, with a salty tongue, glasses on, gloomy and wise.

After we embraced with difficulty, —his body ached, especially his right side—we went into the details I guessed to be less scabrous about the treatment and the disease’s development, which were extreme weakness, feeling like a piece of glass about to crack, spots on the body, and blurred vision. We stopped talking as Gabriel put his index finger on the magazine page. “Do you have all the materials?” he asked gently as if he were an elderly man. I took them out of the little plastic bag. He checked what I had bought, nodded, and looked focused. In effect, he told me that it was all he needed.

“When the slot machine technology advanced, instead of the obsolete and predictable mechanical system, casino owners, especially in the state of Nevada (Las Vegas is there), devised the detection system of the deposited coins through a kind of thin and very precise laser beam, which is impossible for any cheater to fool.” Gabriel said that it was nothing and that he knew exactly the vulnerability mechanism of that technology, which was old-fashioned per se.

“With the materials, I would have it ready in a couple of days.” I asked him how to test the efficacy. He told me that it didn’t matter, but to build the small mechanism in detail, which would be difficult to detect under long-sleeved shirts. “The anti-reflective plastic would do all the work by barely blocking the light beam path and fooling the machine. Just like that.”

I thought it was quite reasonable; although, I asked him again about the practical importance of the whole affair of electronic insect-shaped mechanisms and slot machines in Vegas. Gabriel remained silent. He looked at the gray landscape outside the window—a lot of rusted tin roofs. It was a room overlooking an old downtown residential area. I ran out of damn questions.

For Gabriel, the mechanisms had no practical importance. They were ghosts to palliate his fear and disgust in his anesthetic midnight reverie. “When I leave, I’m going to know more about all this than anyone else. We’re going to the Hotel Palma casino. I’ll loot all the machines, and you’ll keep half of the dough,” Gabriel said smiling.

Of course, he meant it. “I just need to get to know how the old models worked to get to these,” he said pointing with his pale, long, index finger to the shiny sheet. “When I’ve got everything clear, we’ll go away, leave the bench empty, drink guaro all night long, and have a few cigars.” I liked the idea in spite of myself. I asked him if he didn’t have another list of materials he needed. We hugged goodbye. He felt pain again.

I called him just for the second time since he was admitted. It wasn’t too late, but I didn’t think he was going to answer. After saying hello, I didn’t think he was going to talk to me immediately about the most modern slot machines, which were equipped with all sorts of electronic, mechanical, and computer mechanisms. “They were real and almost invulnerable computers.” He added more materials to the list he had given me last time.

He told me about the bone marrow, which created the defective and aberrant-shaped cells and spat them out into the blood. He made a comparison between his body and a slot machine while guffawing. I didn’t remember his exact words, but I found it funny, as well as worrying. His voice was low and comatose when he calmed down.

I imagined him too old and hurt to be alive. “We’ll conquer the damn firebreathers,” Gabriel said, “that’s what they call the most modern ones in Vegas; the fi-re-breath-ers. Imagine what we’re going to do with the ones here, which are second-hand junk.” We said goodbye to each other. I saw myself looting, with Gabriel watching my back, all the casinos in the country, buying all the drinks, and choking on every meal.

I visited him again a few days later. I entered the room, but didn’t find him. I went into the garden outside the room of Masculine Oncology 2 and that of Cardiology, where the sick people rested. Some smoked, which wasn’t strange or shocking but laughable. A nurse had told me I would have to wait for Gabriel.

Anyway, I thought he wouldn’t like my visit. I hadn’t been able to get him all the things on the list. I think some of them didn’t even exist and others weren’t sold separately, but only in bigger kits. Noon and mid-afternoon went by. I phoned Gabriel. The hold sound was repeated until there was no dial tone. I called back again three or four times. Nobody answered at home. I left the hospital.

I returned. He couldn’t see me. He was in a serious condition as the nurse told me. “Serious?” “Yes, serious,” she managed to tell me. I left the hospital again. I called him on his cell phone at night and in the early morning. I also phoned the room of Masculine Oncology 2, but nobody answered. “Serious” was the only word the nurse repeated like a malevolent litany.

It took me 15 minutes less than usual to get to the hospital. I sweated. I entered the room directly without asking for Gabriel. I was greeted by the same two men as always. The 12-year-old boy played with his little, portable device. He greeted me and his face was calm. Gabriel’s bed was arranged, perfect, and empty. None of the sick knew anything. I opened the drawers and the books were still there. The Art of Machines was still there. “No, sir. I think his condition got worse,” a guy I had never seen before told me. I thanked him for the information.