Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

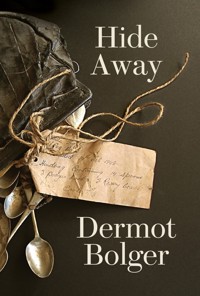

Hidden behind the walls of Grangegorman Mental Hospital in 1941, four lives collide, all afflicted by the human cost of wars, betrayals and trauma. Gus, a shrewd attendant, is the keeper of everyone's secrets, especially his own. Two War of Independence veterans are reunited. One, Jimmy Nolan, has spent twenty years as a psychiatric patient, unable to recover from his involvement in youthful killings. In contrast, Francis Dillon has prospered as a businessman, until rumours of Civil War atrocities cause his collapse, suffering delusions of enemies seeking to kill him. Doctor Fairfax has fled London after his gay lover's death. Desperate to rekindle a sense of purpose, Fairfax tries to help Dillon recover by getting him to talk about his past. But a code of silence surrounds the traumatic violence Ireland has endured. Is Dillon willing to break his silence to find a way back to his family? In this superb evocation of hidden worlds, master storyteller Dermot Bolger explores the aftershock within people who participate in violence and the fault-lines in all post-conflict societies only held together by collective amnesia.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Hide Away

Also by Dermot Bolger

POETRY

The Habit of Flesh

Finglas Lilies

No Waiting America

Internal Exiles

Leinster Street Ghosts

Taking My Letters Back

The Chosen Moment

External Affairs

The Venice Suite

That Which is Suddenly Precious

Other People’s Lives

NOVELS

Night Shift

The Woman’s Daughter

The Journey Home

Emily’s Shoes

A Second Life

Father’s Music

Temptation

The Valparaiso Voyage

The Family on Paradise Pier

The Fall of Ireland

Tanglewood

The Lonely Sea and Sky

An Ark of Light

YOUNG ADULT NOVEL

New Town Soul

SHORT STORIES

Secrets Never Told

COLLABORATIVE NOVELS

Finbar’s Hotel

Ladies’ Night at Finbar’s Hotel

PLAYS

The Lament for Arthur Cleary

Blinded by the Light

In High Germany

The Holy Ground

One Last White Horse

April Bright

The Passion of Jerome

Consenting Adults

The Ballymun Trilogy

1: From These Green Heights

2: The Townlands of Brazil

3: The Consequences of Lightning

Walking the Road

The Parting Glass

Tea Chests and Dreams

Ulysses (a stage adaptation of the novel by James Joyce)

Bang Bang

Last Orders at the Dockside

The Messenger

Home, Boys, Home

HIDE AWAY

First published in 2024 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House, 10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh, Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Dermot Bolger, 2024

The right of Dermot Bolger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-938-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-937-8

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

This book is a work of fiction. While its plot has some roots in events that happened during the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War, and while it uses the real names of certain historical figures associated with those particular events, all the other events described here and all characters who possess fictitious names are entirely the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to any actual living person is entirely coincidental.

Sincere thanks to the artist Alan Counihan for permission to use, on the cover of this novel, a detail from a photograph taken from his 2014 installation, ‘Personal Effects: A History of Possessions’, which focused on belongings left behind by dead or discharged patients from St. Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital, Grangegorman.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Set in Goudy Old Style in 12 pt on 15.3 pt

Typeset by JVR Creative India

Edited by Djinn von Noorden

Cover image detail by Alan Counihan

Printed by L&C, Poland, lcprinting.eu

The paper used in this book comes from the wood pulp of sustainably managed forests.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), Dublin, Ireland.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Diarmuid and Katie, setting forth

Contents

Prologue: Fairfax

One: Agnes

Two: Gus

Three: Dillon

Four: Gus

Five: Fairfax

Six: Dillon

Seven: Superintendent

Eight: Gus

Nine: Dillon

Ten: Gus

Eleven: Dillon

Twelve: Gus

Thirteen: Nolan

Fourteen: Dillon

Fifteen: Gus

Sixteen: Dillon

Seventeen: Nolan

Eighteen: Dillon

Nineteen: Fairfax

Twenty: Nolan

Twenty-One: Gus

Twenty-Two: Fairfax

Twenty-Three: Dillon

Twenty-Four: Gus

Author’s Note

Prologue

Fairfax

25 March 1941: Night Crossing

They met on a voyage from darkness into light. Or so it seemed to Fairfax as he stood on the open deck of the mailboat navigating the night crossing to Dublin. After two years of enforced blackouts in England, Dublin’s lights glittering in the distance looked so unnatural that this might be a journey into a different world. Or a journey back in time – where he often asked his patients to mentally travel – into a lost childhood, when lights could shine bright without a fear of attracting bombers, where the only things that might wake you were a cock crowing or a dog’s bark – not the heart-stopping wail of air-raid sirens or the unearthly whoosh of a falling bomb foretelling the ferocious explosion to come.

He did not know the circumstances of how this woman standing on deck had left London twelve hours earlier. His own journey started in the blacked-out darkness he had grown accustomed to navigating. The headlights of the Wolseley Super Six driven by his friend Christopher, who collected Fairfax from his flat, were cloaked in cardboard with two pinpricks cut into them. This allowed not so much a beam of light as the ghost of a beam, to precariously guide them through unlit streets where even one loose curtain over a window could become a source of consternation and danger.

He didn’t ask where Christopher had acquired the petrol to drive him to the station, and was too distraught to want to know what favours Christopher must have called in to circumnavigate regulations and procure the necessary documents to allow Fairfax to leave Britain.

Some work and travel permits had undoubtedly been procured during hushed conversations in the corridors of White’s Club in St James’s Street, a club steeped in arcane etiquette where gentleman could enjoy the company of fellow gentlemen in the billiards room, as if this Blitzkrieg were just another outside interference to be kept at bay until obsequious servants requested members to adjourn to the relative safety of the wine cellars. Other permits had possibly been acquired from contacts in more secretive clubs like Le Boeuf sur le Toit in Orange Street in Soho, where a different type of gentlemen could risk enjoying the company of other men in a more surreptitious manner.

Fairfax rarely frequented White’s, which he found too stifling, or Le Boeuf sur le Toit, because its decor was too lascivious and its trade a bit too rough for a settled man like himself. But he was known on the fringes of these closeted circles and in other circles too. He frequented meetings of the British Psychoanalytical Society, which, following an influx of members fleeing Vienna, was now beset by schisms between Kleinian and Freudian factions. Since boyhood he had been a member of the local cricket club, where he enjoyed the relative anonymity of being known only for being not as good a medium-pace bowler as his older brother once was and for being considered a disappointment to his ambitious father.

For the past decade Fairfax had been able to partition his life between these different worlds because at heart all he cared about was the unshakable sanctuary that had been at the centre of his existence; the small haven he had created where he could be himself with the man whom he loved; that sanctum in Putney, which he had shared with his lover Charles and which he had thought could only ever be blown apart if a Heinkel had circled overhead and indiscriminately dropped an incendiary bomb on the flat. He could never have expected his world to be shattered by a blast on a shabby side street off the Old Kent Road in Southwark a fortnight ago, which caused two bodies to be found entwined amid the rubble.

When one secret was shattered in the circles in which Fairfax moved, there was always a fear of contamination, of other secrets being exposed among the shards. Therefore, some favours solicited by Christopher on his behalf had been given not only from sympathy for his loss but from self-interest. With his private sanctum destroyed, he might become dangerous to know. Nobody could gauge what secrets a man might inadvertently let slip when trying to make sense not only of a terrible loss but a heartrending sense of betrayal as well.

At the train station, Christopher had paused before getting out to seek a porter for his cases. ‘You do know that Charles loved you?’ he said.

Fairfax shook his head. ‘I’m certain of nothing anymore.’

Christopher turned towards him, but even in the privacy of the Wolseley on a blacked-out street he was too nervous to risk putting a comforting hand on his knee.

‘Charles was always just Charles. He was older than us. You saw in his eyes that he had seen ugly things we never had to see. Maybe he needed to do ugly things too, in Egypt or in Ireland during their damned unrest. I don’t know because a gentleman doesn’t tell. I just know that war was damnable back then and is damnable now. We’re each made up of our contradictions. You know this better than most. You delve into contradictions every day with patients. Few people are just good or evil. Sometimes we yield to temptations that are simply opportunistic; acted out in one moment and forgotten in the next, with no intent to hurt anyone. Charles could show a streak of cruelty, but never towards you. I don’t know how Charles ended up in that flat in Southwark, but from how Charles sometimes gazed at you, I never saw any man so much in love with another. Hold onto that thought and do nothing stupid. Boats have a hypnotic quality. Waves look inviting if you stare long enough. But any poor sod who ever jumped was already regretting the decision before his body entered the freezing waters.’

Fairfax had pondered those words since the train began its cautious journey from London, crawling through dark cities with the blacked-out carriage windows increasing his claustrophobia. There was the brief respite of being let out into the air to queue to board this packed mailboat. The crossing took eight hours longer than before the war, but even at sea some passengers felt apprehensive. Early in the war U-boats had laid mines that caused the MV Munster passenger ship to sink within sight of Liverpool. The Irish Sea was safer since the Royal Navy laid a nest of mines across the St George’s Channel. But magnetic mines could break loose during storms and drift harmlessly until they found a metal hull to latch onto. No stage of this crossing was safe until they caught sight of the neutral, lit-up Irish coastline.

These lights were causing excitement on deck now, beckoning in the dark like the gateway to a luminous funfair. Three well-heeled English passengers paused beside him. Their stance betrayed how – although banned from wearing uniforms in Ireland – they were British army officers, availing of leave to indulge in the pleasures Dublin could offer. Restaurants where they could eat without fretting over ration cards; ballrooms to dance in without fear of air-raid sirens; shops awash with gifts of cosmetics for wives and girlfriends, if guilt required them to atone for any indiscretions during this spree, when pink gin and whiskey were flowing. He heard them make plans: dinner in Jammet’s, then a wager on who could get furthest with any local Judy lining the walls of the Olympia Ballroom. They spoke of Dublin with childlike glee but also with spite, convinced that if they visited local harbours they would spy U-boats surfacing at night to be refuelled, and Kriegsmarine sailors nodding to sly fishermen in pubs, before those German crews disappeared to bring death to honest sailors on the Western Approaches.

‘We’ll gatecrash a dance at the Gresham,’ one man said. ‘It’s easy to sweet-talk your way in and find a better class of Able Grable to ply with gin. If I lure one outside, I won’t take no for an answer. If they’re so free with favours for the Nazis, they can be free with them for us too.’

The others laughed and strode away, leaving him alone in the shadows. Fairfax had frequently travelled by yacht in rough seas, yet a fear of seasickness prevented him from venturing into the bar. Or maybe a fear of getting drawn into conversation with a fellow passenger from his own social class. He lacked the strength to go through the charade of spurious chitchat. Fairfax needed to be alone. Or as alone as one could be with so many passengers traversing this narrow deck, hurrying to join the singsong in the bar or pausing to marvel at the approaching city lights.

In truth, he was in hiding in this semi-darkness, hoping nobody would recognise him. In his early twenties it was the sort of shadowy darkness he had furtively sought out, torn between fear and excitement, between physical needs he tried to suppress and a fear of assault and blackmail, arrest and the disgrace of a court case. Before the war, such clandestine pockets of darkness were hard to find. But, as Charles had recently remarked, the blackout transformed all of London into a vast version of Hampstead Heath, brimming with sexual possibilities. Charles had given him a long glance after saying this, before adding with a laugh, ‘That is, if we still needed to seek such encounters, dear heart, which thankfully we don’t, as we have each other. All I’m seeking these days is a pot of tea stewed with leaves only previously used twice.’

Back then Fairfax hadn’t thought much about Charles’s observation. But now what he recalled most was his long glance. Had Charles been trying to tell him something? Or hoping to lure him into a reply that bestowed permission to go ‘bunburying’, to use his favourite Wilde euphemism?

Maybe Charles meant nothing by it. The Blitz had taught him not to read portents into people’s final remarks. Death came too randomly. No Londoner knew when an incendiary bomb would devastate their home or if they would reach a bomb shelter in time or if their Morrison shelter, doubling as a kitchen table, would bear the weight of rubble until they were dug out. Death could strike as mundanely on Westminster Bridge as on the Clapham omnibus. But surely a cosmopolitan ex-army officer like Charles could never have expected it to seek him out in a bed in that cheap lodging house in Southwark.

Not that Fairfax knew how threadbare the room had been. Little had remained standing by the time the air-raid warden on the scene recognised that Charles – even when naked – did not belong there. Too well fed and groomed in contrast to the equally naked Irish labourer whose body was entwined with his. The warden had searched Charles’s jacket, still attached on the collapsed bedstead, and, seeing Charles’s former rank, deserted his post to telephone the number on his business card. Fairfax recalled the warden’s deferential phone manner as he asked firstly if Fairfax was acquainted with a Mr Charles Willoughby and then, after a pause, if he knew of an Irishman with travel papers that gave his name as James Bourke. The warden had been very hesitant with his questions, sensing from the details on Charles’s business card that he might be dealing with the sort of people who knew important people who would want any scandal to be hushed up.

Fairfax now wondered whether he had spent ten years intimately getting to know Charles, only to discover that he didn’t truly know him at all. Their age difference meant that Charles had witnessed butchery and horrors in the Dardanelles and Egypt that Fairfax’s youth shielded him from until his first posting to France during the final months of the Great War. But if he never witnessed whatever horrors Charles endured, Fairfax had witnessed the nightmares that arose from the trauma of those unmentioned events. On some nights Charles would shudder and shout out in his sleep, waking in such dazed confusion that he could only regain his equilibrium by spooning into Fairfax’s body, nuzzling his naked back and then, as his breathing slowly returned to normal, planting a kiss on Fairfax’s ear before murmuring, ‘Ambushed again, dear heart. Hope I didn’t frighten you.’

But on other nights, Charles’s hardened state of arousal upon wakening had allowed for no such endearments, with Fairfax knowing that the silent fucking he was about to receive would be long and merciless. This rough sex felt both intimate and anonymous, with Fairfax occluded from whatever memories made his lover’s cock so rigid. Only once had he deciphered a whisper – ‘beg for it to the hilt … tight Irish arse …’ – words so barely audible that he was unsure if Charles was awake or asleep, fantasising or reliving a memory. These uncharacteristic outbursts of sexual dominance – over which Charles, in his agitation, appeared to have little control – left Fairfax feeling bruised, inside and out, and yet oddly loved and needed. In those moments he became the poultice for Charles’s pain, even if Charles was so exhausted by his climax that he generally fell back asleep within moments, barely aware of Fairfax being left to spill his own seed across his lover’s naked chest, adorned with the scar of a bullet hole, the souvenir of an ambush in Tipperary in 1920.

But generally, their sex was not like that. It was companionable and relatively gentle, if lacking the intensity of the early years when every coupling felt like a treasure snatched from a judgemental world. Charles’s unexpected violence during those rare nocturnal couplings was never mentioned, though, sometimes next morning, he would kiss Fairfax’s neck lightly and murmur, ‘Hope I wasn’t over boisterous last night, dear heart. I was barely awake. I don’t know what came over me. I’d never intentionally hurt you. I love you too much. You know that, don’t you?’

Standing on the deck of this ship now, he was certain of nothing. The first rule for any psychoanalyst was to never psychoanalyse one’s partner. Charles and he lived together for so long that it felt akin to a marriage. Charles professed little patience for his field of ‘quack medicine’, as he sometimes disparaged it. But even if Fairfax had persuaded him to lie on a couch, Charles could never have been lured into reliving what turned him into a predator on nights when his unloosened brutality scared and excited them both. Fairfax wasn’t sure if this sadism stemmed from experiences in Egypt or serving in Ireland after the Great War or if this quirk of sadism was always latent inside Charles and might have emerged anyway, even if war had not interrupted his career as a stockbroker and a name in Lloyds.

Mostly they had kept their very different public lives separate, despite very occasionally pretending to be brothers. Charles had enjoyed immersing himself in risks and profits from stocks and shares, deals involving tangible commodities. It had been a mistake to lure him some months ago to a fractious meeting of the British Psychoanalytical Society, where the conceptual theories being passionately espoused merely exasperated him. This had led to a rare row, after Charles opened the whiskey decanter back in their flat. But also to a rarer glimpse into Charles’s time in Ireland, as he mocked the debate he had been forced to sit through. It was also the first occasion that Fairfax heard the name of the asylum to which he was now travelling to take up his new post.

‘All your theorists can do is just drone on about vague abstractions,’ Charles had snorted after several whiskies. ‘God help any poor bastard seeking help from them. Don’t tell me you honestly believe that lying on a couch and bleating out your inner thoughts does anyone any good? People who go mad need to be shaken out of madness. I know. I saw the inside of an asylum while you were still in boarding school. Grangegorman in Dublin – a hellhole in which, to be honest, you’d be too soft to ever work. Don’t worry; I wasn’t in Grangegorman to be dosed with strychnine syrup or plunged into hot and cold baths to revive my spirits and scrunch up my scrotum. I rarely set foot in the main asylum there, thank God, because it was rife with tuberculosis and dysentery. The army kept our shell-shocked soldiers in a separate military wing and blotted their names out of the asylum’s records, so our lads could walk away with no stain of ever being certified as insane. They were honest, decent chaps, sunk into themselves after enduring such horrors that they heard voices and explosions in their sleep or even when awake. The doctors did their best, but with proper drugs, not abstract nonsense. There’s no point in asking a man suffering from neurasthenia if he wet the bed as a child, when he’s so disturbed after seeing his pals blown to shreds that he’s shitting himself in his sleep.’

‘What were you doing visiting that asylum?’ Fairfax had asked, humiliated at how the evening had gone. ‘Shouting at patients to buck up?’

‘I was helping those lads who could do so to buck up,’ Charles replied. ‘With those who couldn’t, I just sat with them, sharing cigarettes or helping to write letters. It was the first time many had ever properly spoken to an officer, though some were so feeble-minded they could barely form a sentence. But when I saw a spark returning to other chaps, I did as much good as any doctor. The Irish Automobile Association put a motor at my disposal. I’d take them out of that rancid asylum and out of themselves. Fresh air in the Wicklow hills, the freedom to swim naked in a lake and then just lie there, feeling the sun on their pelt. Sometimes doctors were angry with me bringing them back so late, but during their day with me they felt like men again, not just patients to be pitied.’

‘And what kept you and them so late up the Wicklow hills?’ Fairfax remembered feeling an irrational stab of jealousy.

Charles had fixed him with a stare. ‘Few stayed up there late with me but any who lingered did so willingly. Our kind can always find tell-tale signs to recognise each other, even in those who never faced up to admitting their nature to themselves. Stretching out naked after a swim is the easy way to sort the wheat from the chaff. I’d just lie there, smoking, gazing up and, if it was in their nature, then I’d pretty soon sense their furtive glances at my body. Some lads were so innocent I was often their first time. “What if I can’t keep a stiff upper lip, Sir,” one Dublin lad asked me. “Don’t worry,” I said, “it isn’t your lip that I’ll teach you how to keep stiff.”’

Charles had laughed, expecting him to join in, but whiskey had soured the mood between them.

‘Is that where you learnt to be rough?’ Fairfax had felt a need to hurt him.

Charles’s smile disappeared. ‘I was rough to no man in Ireland. Not back then, just after the Armistice when it was still safe for an officer to drive about. Ireland changed soon after. You never knew what baby-faced cornerboy was lying in wait to put a cowardly bullet in your back. After the murders started, everything was off the table or, if the ghastlier of my fellow officers were drunk enough, I’d find men bent across it.’

Their quarrel had lasted for days, neither of them knowing how to resolve it, angrier with themselves than with each other. Finally, Charles had found the consolatory words. ‘I spoke out of turn the other night, dear heart. The whiskey talking. I’ve no doubt that you do good in your work. Don’t think of me badly. Any encounters I had before I met you needed to be furtive and quick, with often no words spoken. But it kills me that you might think I ever took advantage of any man.’

‘It kills me that you think me too soft to work in an asylum like Grangegorman.’

Charles had reached his hand across the table. ‘I don’t think you’re soft, dear heart. It took moral courage for you to resign from your last job over the ragging of that conscientious objector which went too far. I don’t think of Ireland often. I’ve forgotten most of my good memories and can’t forget my bad ones about that blasted country. Promise me you’ll never think of working there. The asylums would break your health and then break your heart.’

He was on this boat now partly to prove Charles wrong in thinking that he lacked the strength to cope in somewhere like Grangegorman. Even if working in such a place gradually decimated his soul, having to focus on the labour involved might just save him from thoughts of killing himself. Remembering any conversation with Charles now anguished Fairfax. He was overwhelmed by grief, yet even this grief was soured by a paralysing anger at having been betrayed in a cheap lodging house.

His thoughts kept returning to the night when he was summoned to that collapsed building in Southwick, but he was so lost in self-absorption that it took him a while to realise why. Then gradually Fairfax became aware his gaze had honed in on a solitary figure at the rail. It was windy on deck in this hour before dawn, yet she seemed oblivious to the cold. She gazed at Dublin’s distant lights but seemed barely aware of them. He had never seen anyone look so alone and lost. The lighting on deck was so dim that it defied logic to feel convinced that he recognised her, having only glimpsed her twice before. Their first encounter had possessed a nightmarish quality when she arrived at the rubble of her former home in Southwark to find neighbours digging with their bare hands and pointedly ignoring Fairfax, who was sobbing and openly stroking Charles’s forehead. He had been saying God knows what, with all normal discretion gone, while Charles’s body lay beneath the same blanket that concealed the naked corpse of the husband who had betrayed this woman.

The second was a glimpse of her being consoled by other Irish emigrants two days later at James Bourke’s funeral in an RC church, where Fairfax had tried to sit unobtrusively in the back pew, knowing that he was intruding on someone else’s grief but unable to stay away from what had felt like a final link to Charles. He had known, from her venomous glare when glimpsing him there, that she resented his presence.

If he approached now on deck, she might suspect him of stalking her. Her presence on board made sense. She was presumably returning home to be consoled by her kin. But his presence here would be inexplicable to her, voyaging to a city where he knew nobody and hoped that nobody knew him. Fairfax had never even previously visited Ireland, put off by Charles’s reticence about discussing his army years there, which he had dismissed as ‘a shambles of brutality and brandy, best forgotten’.

It was the cruellest irony that, during this crossing, Fairfax had chanced upon the only person who might understand the paradoxical emotions destroying him. He had no right to further intrude on this widow’s grief and might have remained watching from the shadows if something about the way that she kept leaning over the rail had not alarmed him. Those waters were icy. Nobody was paying her attention, yet surely someone would hear the splash. He had no idea how long it would take this creaking ship to turn and try to search the waves into which she might disappear.

Her death should be her own business. She had endured enough. Fairfax had no right to interfere. But the Hippocratic Oath he once swore – the primum non nocere clause – made him step forth and grip her elbow when her body lurched forward as the ship struck a wave. She recoiled from his touch, even before recognising him. When she did, she was so startled that it took her a moment to speak.

‘What the hell do you want? Haven’t your sort already done enough to me! Get away or I’ll scream to let folk know what class of deviant you are!’

‘Please,’ he said, ‘I don’t mean to alarm you. I was just worried.’

‘About what?’ She glanced at the waves. ‘That I’d jump? Why would that worry you? It would be one less person alive who knows your dirty secret.’ She paused and stared at him angrily. ‘What are you even doing here?’

‘Not spying on you, I swear. But it’s slippery out here. So just promise you’ll move back from the rail.’

‘What would you do if I jumped? Dive in to rescue me like a gallant gent?’

‘I might dive in,’ Fairfax replied after a pause. ‘Not to rescue but follow you. There has been no day in the past fortnight when I haven’t thought about escaping this pain by ending it all.’

His words lessened her aggressive tone. ‘I’ve not thought about you,’ she said. ‘Beyond thinking that I’d like to put a knife in you. But what good would that do? The night I came home to find you sobbing over those two bodies, I realised you were as duped as I was. Equally clueless. Even when you think you know men, you can’t trust them. But my Jem wasn’t like your perverted friend. Jem was from Dominick Street in Dublin. He had trials playing soccer for Bohemians. You don’t get queers in Dominick Street.’

‘Are you sure?’

She shook her head. ‘A fortnight ago I thought I understood my world. But not anymore.’ Her tone sharpened. ‘You had no right to attend Jem’s funeral. People were asking who you were.’

‘What did you say?’

‘I lied and said you were the warden who found his body, piled among other bodies in the hallway, all of them trying to reach the air-raid shelter.’ She paused. ‘The sirens were going. The tube station only a hundred yards away was packed with people. I keep asking, why hadn’t they enough sense to get to safety with everyone else?’

She glanced away. ‘But that’s the old naive me thinking. They didn’t want to be with other people. The sirens must have sounded like music. It meant that every other flat in the house was empty and they could do as they pleased, as loudly as they pleased. But it makes no sense because my Jem wasn’t like that.’ Her voice lost conviction. ‘Or was he? Was money involved? We found it hard to make ends meet, but Jem wouldn’t … not that way … even if we had debts I didn’t know of. Jem liked to gamble … he liked risk … but he’d never do such a thing.’ She turned to Fairfax. ‘At least have the decency to explain all this to me.’

‘If I could, I would. I didn’t know your Jem, or James as he was called on his work permit. But maybe I didn’t know my friend Charles either, despite ten years under one roof.’

‘Ten years.’ She took this in. ‘Jem and me only had eighteen months. But they were eighteen natural months. We were a married couple.’

‘I know,’ he replied softly. ‘But grief isn’t a competition.’

She nodded. Both lapsed into silence. There was just the splash of waves against the hull, a whistling sea breeze and murmurs of conversations around them. No other passengers lingered to eavesdrop or pay them any heed. They could think of little to say, having nothing in common. Nothing and everything. Sharing the accidental and unwelcome bond of being the keepers of each other’s secret. Perhaps it was good to know so little about each other. No words exchanged here would get back to anyone who knew either of them. A secret unshared can drive a person into the depths of insanity. Talk was as essential a cure for the mind as penicillin was for the body. To keep the truth hidden away was an invisible form of cancer. Fairfax knew this, as a psychoanalyst. But he felt as lost as any patient who ever lay on his couch.

He thought of Luke 4:23 in the King James Bible. ‘Physician, heal thyself.’ Fairfax didn’t share this quotation with her. Roman Catholics – as far as he knew – were not encouraged to read the Bible and certainly not the version reshaped by forty-five Protestant biblical scholars to elevate their king. Glancing at her face, as she stared towards Dublin’s lights, he knew that when this boat docked she would disappear from his life. The only thing they would take away were the hidden aspects of each other’s lives. She could never talk about this without it bringing judgement on her late husband. She felt his gaze and looked up.

‘What sort of welcome will you get from your family?’ Fairfax asked.

‘It will beat the welcome I got in England when I made this crossing two years ago. Men spraying delousing powder over my hair and a stuck-up Foxrock Dublin Protestant doctor looking down her nose as she made me strip to my shift to check for lice and ask how often I washed. I’ll take that guff from your sort but not from the likes of her.’

‘Is a Foxrock Dublin Protestant not one of your own?’

‘They’re neither flesh nor fowl,’ she replied bitterly. ‘I had to pretend to be twenty-two to get a permit to go to England. The Garda stamping my travel pass knew I was too young, but also knew there were enough of us sharing one bed and my parents needed me to be sending home a few bob. But I only had to bluff my way in. Jem had to tell outright lies because he had been an agricultural labourer and Dev is forcing them buckos to remain in Ireland and work for a pittance.’ She looked at him. ‘Before Jem left the Dominick Street flats to get a job on a farm in Meath, he said that he had never once eaten a piece of fruit or a fresh vegetable. But he just wanted to get away from Dublin and spun lies to persuade a farmer to take him on. I used to laugh with him about the other lies he spun to get his travel pass to London because Jem was great at spinning yarns. I just didn’t know he was spinning them to me.’

‘I’m sorry,’ he said softly. ‘I know how you feel.’

Her face hardened. ‘It has nothing to do with you, and you have nothing to do with me. When you saw me at this rail, why couldn’t you have just walked on?’

‘You looked so alone,’ he said.

‘I am alone.’

‘You have family waiting. I don’t know a soul in Dublin.’

‘Then why come here?’

‘Sometimes you need to go where nobody knows you.’

‘I’m being bitchy,’ she said quietly. ‘I can’t help it. I’m so angry. I should be angry with Hitler but I’m too busy being angry with Jem. I want to take him in my arms, yet I want to scratch out his eyes. What unearthly class of man was he?’

‘Why ask me?’ Fairfax said. ‘You were married to him.’

‘The best eighteen months of my life. He had his oddities, but I thought nothing of them because I knew nothing about life.’

‘Did you love him?’

‘He swept me off my feet. Six weeks between the night we met and our wedding. I couldn’t believe he picked me instead of every other girl dying for him to put a ring on them. For the first time I felt special. Now I feel that something must be wrong with me.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’

‘There sure as hell was something wrong with him. And you too. No disrespect.’

He produced a leather notebook, wrote some words on a page and tore it out. ‘This is my address in Dublin if there is anything I can ever do for you.’

She glanced at the slip of paper and nodded.

‘It’s good you’re going in for treatment,’ she said. ‘I didn’t know they treated your abnormality in there, but, God knows, they treat every other affliction.’

‘I’m not there as a patient,’ he said. ‘I’m going to work as a doctor.’

‘Of your own free will?’

His nod was rewarded with a look of incredulity.

‘Surely a man of your education can find a better job?’

‘If I wanted to, yes, but I don’t. I need to get away from London. I also want to do some good.’

‘You want to hide away, you mean? Well, your secret will be safe in Grangegorman. Those walls hold thousands of them.’

‘Have you been inside that asylum?’

A defensiveness entered her voice. ‘Are you accusing me of being astray in the head? No amadáns in my family ever needed to be carted off to that puzzle factory.’ She paused. My professional instincts cautioned me against speaking before she spoke again. ‘Though just because no one ever needed to be, doesn’t mean that nobody ever was. I’ve a class of aunt locked up in Grangegorman.’

‘What class of aunt?’

‘The class no one mentions. She lived under her mother’s roof for fifty years, though I’m not sure of her exact age and by now she probably doesn’t know herself.’

‘Do you mean that she is delusional?’

‘I mean that she was in her brother’s way after he inherited the farm when their mother – a vindictive hag – had the decency to finally oblige him by dying. I suppose nobody can blame him for wanting to make a spinster sister disappear. But in my book he’s a hard-hearted bastard. In London I earned fifty-six bob a week as a carney girl in a munitions factory. Dirty work, my hair yellow from ladling sulphur, but it was more than my uncle earned from his tight-fisted mother in a month. Thirty years at her beck and call, running the farm for pocket money. I saw him collect old washers, to have something to jangle in his pocket that sounded like coins when he went out. He slaved from dawn to dusk because of the prize his mother dangled before him; that he could move in a young wife under her roof once she was dead. Until then, she would buck no rival and have no painted hussy, as she called them, preening as the woman of the house. Not that you’d find many painted hussies in Castleblaney, unless they can make mascara from cowshite. But you’ll find women desperate enough to flutter their eye at an ageing bachelor with fifty-two acres and lumbago. My uncle was no great catch but the sea doesn’t come in as far as Castleblaney so there’s not many fish to choose from. Women will settle for a man who’s already old, and will make them old by having babies as he tries to catch up for lost time while he has some faloorum, fadidle eye-oorum left in him. But they’ll not move into a house with a spinster sister-in-law moping in the kitchen.’

‘You are referring to your aunt?’

‘Nobody refers to her. She’d have been better in a coffin than in Grangegorman. If she was under the ground, no nightly rosary would be said without her name being included among the prayers for the departed. When you’re dead, queer habits are recalled as amusing quirks, not used as nails to crucify you.’

‘Had she quirks?’

The woman turned to him. ‘You have some cheek asking. It’s more than quirks that you and your blaggard friend had.’

‘My relationship with Charles had to be undefined. A case of acta non verba.’

‘I mightn’t know Latin, but I know that sin is sin in any language. And I now know something of your filthy codology. Everything arseways and back to front. But I was so innocent leaving Castleblaney that I didn’t know that men like you existed. I was so innocent that it wasn’t until the older women I work with rushed to an air-raid shelter and our tongues loosened, that I got some clue because they started laughing when I described how Jem and I went at it. Before that I presumed a girl was always meant to kneel up, like Jem instructed me to, because I had no one to tell me any different.’

She stared again towards Dublin’s lights creeping closer. A passenger walking behind them pointed out the flash from the Bailey lighthouse to his travelling companion. Fairfax knew that she felt exposed for having said too much. It was presumptuous to think that he could fathom the cocktail of emotions she must be enduring. But something of her conflicted feelings surely echoed his own unbearable grief that was relieved only by surges of fury at having been betrayed. She and Fairfax seemed separated from every passenger on deck and yet, despite their similar grief, equally separated from each other.

‘You needn’t tell me such details,’ he whispered. ‘These are not matters to discuss with a stranger.’

She turned to him, her eyes betraying how long since she last slept. ‘Who the hell else can I ever discuss all this with? Not even with a priest in confession, although it’s a mortal sin to hold anything back. But if the punishment for a false confession is hell, I’ll take it because this feels like hell. I’m only talking to you because, after this boat docks, I’ll never see you again and you’ll encounter no member of my family.’

‘Except maybe your aunt in Grangegorman.’

‘I’ve not told you her name.’

‘Trust me. I would never betray your confidence.’

She looked away, wounded. ‘I’d have trusted Jem with my life. I’m so broken I’ll never trust anyone ever again.’

‘I know.’

‘How could you know?’ she said angrily. ‘You haven’t lost a husband.’ She stared at him closely. ‘Don’t say you thought of your friend like that. Your loss is nothing compared to mine.’

‘I don’t presume to fathom the depth of your loss,’ he replied. ‘Please don’t presume to fathom mine.’

‘They’re not alike.’

‘No. When you disembark, you can discuss yours. Widowhood gives you status. People will sympathise, make allowances, understand you are grieving. I’ll never be able to speak of this again. For years I needed to hide my love. Now I must hide my grief.’

‘You won’t be able to hide if I write to tell the Superintendent in Grangegorman that you were in an unnatural relationship.’

He nodded. ‘If that’s your wish then I can’t stop you.’

She looked away, her anger dissipating. ‘I’d never do that, because I’d also have to say how my husband was in an unnatural relationship with the same man.’

‘Had you no idea?’ Fairfax asked.

‘Had you?’

He shook his head. ‘The life I am forced to lead has made me used to deception, threats of blackmail and disgrace. When you met Jem, I imagine that your friends were thrilled to see you settle down. With men like me, the pressures are reversed. Shared domesticity is dangerous and frowned on. Short liaisons are safer. But Charles and I never cared what our friends thought. In our early days we had adventures, sampling the delights that Morocco can offer. But we saw men there grow old and foolish and none of those temptations matched the joy of being able to turn a key in a front door and call someone’s name; the pleasure of sharing a bowl of soup in companionable silence. We no longer needed to seek release in dark alleyways. What we possessed was too precious. We both understood that, or I thought we did, until that air-raid warden scrambling through the wreckage recognised that Charles was a toff. When he phoned, he asked no questions, but people who hear my accent rarely do. He covered their bodies with a sheet until I arrived and went back to helping to dig in the rubble.’

‘What would the warden have done if he’d discovered Jem with another navvy?’

He shook his head. ‘I don’t know.’

‘It’s your country, you should know.’

‘It has never felt like mine. I don’t feel that I possess a country but I possess a vocation. I am a doctor. I try to help people trapped in pain to at least understand their pain. I don’t mend broken bones. I deal with invisible wounds, maybe because my private life had to be invisible until Hitler blew both of our worlds apart.’

‘Hitler robbed me of my husband, but your friend robbed me of my right to grieve.’ She looked up at me. ‘How can I grieve someone I loved but then discovered that I never truly knew?’

‘Were no hints dropped?’

She gave a wistful laugh. ‘You don’t know Irishmen. They’re like closed fists. You’d decode Greek quicker. Even talkative Irishmen don’t say anything beyond bluster. Discussing the weather or Gaelic football or Queen Victoria being a bitch. They’ve never forgotten her heartlessness during the Famine, but don’t ask if any of their own families starved to death, because the shutters come down on things they want to forget.’ She paused. ‘Mother of Jesus, why couldn’t Jem have been found shacked up with a cheap floozy? I’d hate him but at least I’d understand him.’ She looked away. ‘When I said he asked me to kneel up, I don’t mean we did anything unnatural. I knelt because he liked it. But I didn’t like it. I kept thinking I must be so ugly that he can’t bear to look into my face.’

‘You mustn’t think like that,’ he assured her.

‘How should I think?’

‘That he loved you because I’m sure he did. If he’d been with another woman then I’d suspect that he didn’t love you because what could she give him that you couldn’t? But maybe deep inside – and I doubt he understood it himself – he needed something no woman could give. It’s a curious consolation, but all I can think to give you.’

She stared at him. ‘If that’s my only consolation, it leaves you with no consolation at all. I don’t know what pleasures my Jem gave your friend, but they were nothing you couldn’t have given just as easily.’

‘I know.’

‘So where does that leave you?’

‘On my way to a job in Dublin. That was plan A anyway.’

‘What was plan B?’

The boat had steered its way between two long stone piers stretching into Dublin Bay. More people came on deck, attracted by the lights and sense of arrival.

‘What a friend in London cautioned me against. A dark crossing on a crowded boat. Nobody would miss a passenger who slipped overboard.’

‘What stopped you?’

‘I think you did.’

‘Get away out of that.’ She blushed. ‘You don’t even know me.’

‘From how you were stood alone, gripping this rail, I feared for you and I wanted to see you safely to shore.’

‘I never asked you to play at being my saviour.’

‘Maybe it was you saving me.’

‘Or maybe the thought of how long it might take to drown, floundering among those waves.’

He nodded. ‘Maybe you’re right and I’m a coward.’

She shook her head. ‘I was thinking of myself floundering in those waves before you appeared. Maybe we saved each other or for me maybe it was the thought of suicide being a mortal sin. I’d go straight to hell. Jem – for all he did – was still a decent man who would only be condemned to purgatory. So it wasn’t the fear of not seeing God’s face that stopped me. It was the fear that I’d never see Jem again to ask if our love was real. The fires of hell are nothing compared to the need for answers.’

‘I know,’ he said softly.

For the slightest half second she placed her cold hand over his on the rail.

‘I know you know,’ she said. ‘Jem was gentle. Never laid a finger on me. But I’d sooner he’d have beaten me black and blue than leave me like this, burdened by his secrets.’

Fairfax was silent while the three off-duty army officers he had overheard earlier came out on deck, keen to be the first passengers off. Even after they moved away, he hesitated. ‘Charles was a gentleman,’ he said finally. ‘But he wasn’t always gentle. With men like us, sometimes the older man is dominant. The younger man accepts this because it makes him still feel young in his lover’s eyes.’

Anxiety entered her voice. ‘You don’t think Charles ever hurt my Jem?’

He shook his head. ‘When I saw how your husband’s body was strong and toughened from manual work, I knew Charles was after something I couldn’t give. Maybe I’d become too compliant for his tastes. Do you know anything about radium?’

‘No.’

‘It’s powerful but has a poisonous toxicity. Maybe all power is toxic. Charles liked me to kneel up too. He chain-smoked. One night recently, when we were doing what men do, he shocked me by stubbing out a cigarette butt on my skin.’

The woman blessed herself. ‘That would shock anyone.’

‘I wasn’t shocked by him,’ Fairfax said. ‘I was shocked by myself. Shocked to discover that I found myself excited by that pain.’

‘Mother of Jesus. What class of man are you?’

‘One, it seems, who didn’t know my own nature. Charles leaned over me that night and whispered, “In Ireland that’s what we used to call doing an Igoe.” But if Charles had tried to do that with your husband, then Jem would have broken his jaw. I didn’t and maybe that was when I lost his respect by not lashing out. Grangegorman sounds like hell but if I can find one patient who needs my help then just maybe I can cure him in lieu of curing myself. It’s not much but just now it’s the only thought that gives my life any purpose.’

The ship was docking at its berth on the North Wall, ropes being tied up, a rudimentary gangway waiting to be put in place.

‘You won’t be able to do much for my aunt,’ she said. ‘You can’t cure someone who wasn’t mad in the first place.’

‘Then how did your family get her admitted?’

‘A note from the local priest. Priests know what side their bread is buttered on. When a postal order arrives from England, a shilling falls into a priest’s palm every time the money changes hands. There’s cash in weddings and christenings, and no married farmer wants to be shamed when the priest reads out the exact sum that each parishioner contributes to the Easter dues. A spinster is useful for arranging altar flowers but the only money a priest will earn from her is from her funeral. Everyone saw it coming, except for my aunt and me. Or maybe she knew all along and it was her unspoken fear that caused her to start acting so oddly. This gave her brother the cover he needed.’ She looked away. ‘God forgive me, but I was involved in deceiving her.’

‘In what way?’

‘I was her favourite niece. She had a childlike quality. Sometimes as a treat I was allowed to stay over and sleep in her bed. The pair of us whispering and giggling until her mother thumped the bedroom wall with her stick. My aunt’s spirits sank when her brother got engaged. They told her she was just going to Dublin to see a doctor for a check-up. A few tests, maybe an X-ray. We’d leave her with the doctors for an hour and then call back for her. God forgive me for agreeing to go in the car, but I’d never seen Dublin and never thought that her brother would abandon her. And they knew she would make no fuss because she trusted me. Us holding hands in the back of Seamus Quinn’s hackney car all the way to Dublin. We stopped at the Brock Inn near Finglas – the two men going in for whiskeys, sending out minerals for us waiting outside. Lovely countryside. The last view she saw not blocked by a wall. Grangegorman looked like a prison. High barred windows, a huge wooden door. I wanted to go in with them but my uncle told me to stay in the hackney. My aunt looked petrified. All I could do was squeeze her hand and say it would be fine. The doctors were educated men. They’d chat to her and realise that nothing was wrong, except that she was a bit down in herself. I don’t know what they thought because my uncle was barely in the door before he ran back out like the asylum was on fire. I asked him what the doctors said but he told me to shut up and told Quinn, “Drive like fuck, man. Put your foot down and don’t stop till we’re safely back at the Brock Inn.”’

‘You never saw her again?’ Fairfax asked.