4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

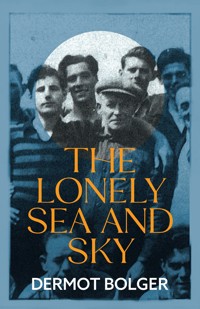

'Myles Foley gripped my soaked jumper. Before his ship sank he was a Nazi: now he's a drowning sailor. Out here, we are all sailors. Your father and grandfather understood that. Are you going to disgrace their memory?' Part historical fiction, part extraordinary coming-of-age tale, The Lonely Sea and Sky charts the maiden voyage of fourteen-year-old Jack Roche aboard a tiny Wexford ship, the Kerlogue, on a treacherous wartime journey to Portugal. After his father's ship is sunk on this same route, Jack must go to sea to support his family swapping Wexford's small streets for Lisbon's vibrant boulevards: where every foreigner seems to be a refugee or a spy, and where he falls under the spell of Katerina, a Czech girl surviving on her wits. Bolger's new novel is based on a real-life rescue in 1943, when the Kerlogue's crew risked their lives to save 168 drowning German sailors - members of the navy that had killed Jack's father. Forced to choose who to save and who to leave behind, the Kerlogue grows so dangerously overloaded that no one knows if they will survive amid the massive Biscay waves. A brilliant portrayal of those unarmed Irish ships that sailed alone through hazardous waters; of young romance and a boy encountering a world where every experience is intense and dangerous, this is Bolger's most spellbinding novel, and the work of a master storyteller who is one of Ireland's best-known novelists, playwrights and poets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

About the Author

Born in Dublin in 1959, the novelist, playwright and poet Dermot Bolger is one of Ireland’s best-known writers. His fourteen novels include The Journey Home, A Second Life, Tanglewood,The Lonely Sea and Sky and An Ark of Light. In 2020 he published his first collection of short stories, Secrets Never Told. His debut play, The Lament for Arthur Cleary, received the Samuel Beckett Award. His numerous other plays include The Ballymun Trilogy, charting forty years of life in a Dublin working-class suburb; and most recently, Last Orders at the Dockside and an adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses, both staged by the Abbey Theatre. His tenth poetry collection, Other People’s Lives, appeared in 2022. He devised the bestselling collaborative novels Finbar’s Hotel and Ladies Night at Finbar’s Hotel, and edited numerous anthologies, including The Picador Book of Contemporary Irish Fiction. A former Writer Fellow at Trinity College Dublin, Bolger writes for Ireland’s leading newspapers, and in 2012 was named Commentator of the Year at the NNI Journalism Awards. In 2021 he received The Lawrence O’Shaughnessy Award for Poetry.

dermotbolger.com

Praise for Dermot Bolger

‘A fierce and terrifyingly uncompromising talent … serious and provocative.’

Nick Hornby, The Sunday Times

‘Bolger does it masterfully, as always. He has been prying open the Irish ribcage since he was sixteen years old…. Pound for pound, word for word, I’d have Bolger represent us in any literary Olympics.’

Colum McCann, Irish Independent

‘Bolger is to contemporary Dublin what Dickens was to Victorian London: archivist, reporter, sometimes infuriated lover. Certainly no understanding of Ireland’s capital at the close of the twentieth century is complete without an acquaintance with his magnificent writing.’

Joseph O’Connor, Books Quarterly

‘Joyce, O’Flaherty, Brian Moore, John McGahern, a fistful of O’Briens … Dermot Bolger is of the same ilk … an exceptional literary gift.’

Independent UK

‘Whether he’s capturing the slums of Dublin or the pain of a missed opportunity in love, Bolger’s writing simply sings.’

Sunday Business Post

‘Dermot Bolger creates a Dublin, a particular world, like no one else writing can … the urban landscape of the thriller that Bolger has made exclusively his own.’

Sunday Independent

‘A wild, frothing, poetic odyssey … a brilliant and ambitious piece of writing.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘The writing is so strong, so exact … triumphantly successful – bare, passionate, almost understating the almost unstatable.’

Financial Times

THE LONELYSEA AND SKY

Also by Dermot Bolger

Poetry

The Habit of Flesh

Finglas Lilies

No Waiting America

Internal Exiles

Leinster Street Ghosts

Taking My Letters back

The Chosen Moment

External Affairs

The Venice Suite

That Which is Suddenly Precious

Other People’s Lives

Novels

Night Shift

The Woman’s Daughter

The Journey Home

Emily’s Shoes

A Second Life

Father’s Music

Temptation

The Valparaiso Voyage

The Family on Paradise Pier

The Fall of Ireland

Tanglewood

An Ark of Light

Young Adult Novel

New Town Soul

Short Stories

Secrets Never Told

Collaborative Novels

Finbar’s Hotel

Ladies Night at Finbar’s Hotel

Plays

The Lament for Arthur Cleary

Blinded by the Light

In High Germany

The Holy Ground

One Last White Horse

April Bright

The Passion of Jerome

Consenting Adults

The Ballymun Trilogy

1: From These Green Heights

2: The Townlands of Brazil

3: The Consequences of Lightning

Walking the Road

The Parting Glass

Tea Chests & Dreams

Ulysses (a stage adaptation of the novel by James Joyce)

Bang Bang

Last Orders at the Dockside

The Messenger

THE LONELY SEA AND SKY

First published in 2016 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

This edition published 2022

Copyright © Dermot Bolger, 2016, 2022

The author has asserted his moral rights.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-772-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84840-871-5

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Front cover photograph features the crew of the Irish Poplar – one of many Irish ships mentioned in this novel – taken by Martin Cunningham in 1945. It is reproduced, with thanks, from Captain Frank Forde’s classic work, The Long Watch: World War Two and the Irish Mercantile Marine (New Island Books, 2000).

Cover Design by Fiachra McCarthy, fiachramccarthy.com

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíonn). Dublin, Ireland.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

In memory of my father,Roger Bolger (1918–2011)of Green Street, Wexford town,who voyaged to Lisbon on the MV Edenvale:sister ship of the MV Kerlogue.And remembering his neighbour who took him to sea,Michael Tierney of Green Street, Wexford town,who lost his life on the MV Cymric,sunk in the Bay of Biscay, February 1944.

Contents

Prologue

Part One: THE VOYAGE OUT

Chapter One: 14 December 1943, the Wexford quays

Chapter Two: 14 December, the Wexford quays

Chapter Three: 15 December, Wexford town

Chapter Four: 15 December, St George’s Channel

Chapter Five: 16 December, Bristol Channel

Chapter Six: 17 December, Cardiff

Chapter Seven: 17 December, Cardiff

Chapter Eight: 21 December, Morning Watch, Bay of Biscay

Chapter Nine: 21 December, First Dog Watch, Bay of Biscay

Part Two: LISBON

Chapter Ten: 23 December, Belém, Lisbon, First Watch,

Chapter Eleven: 24 December, Alcântara, Lisbon

Chapter Twelve: 24 December, 11 a.m. Lisbon

Chapter Thirteen: 24 December, Lisbon

Chapter Fourteen: 24 December, Lisbon

Chapter Fifteen: 24 December, Bairro Alto, Lisbon.

Chapter Sixteen: 24 December, Bairro Alto & Alcântara

Chapter Seventeen: 24 December, Alcântara & Rossio, Lisbon

Chapter Eighteen: 25 December, Alcântara & Rua do Arsenal, Lisbon

Chapter Nineteen: 25 December, Bairro Alto, Lisbon

Chapter Twenty: 25 December, Bairro Alto, Lisbon

Chapter Twenty-One: 25 December, Alcântara, Lisbon

Part Three: THE HOMEWARD VOYAGE

Chapter Twenty-Two: 28 December, Afternoon Watch, Bay of Biscay

Chapter Twenty-Three: 29 December, Morning Watch: 260 Miles South of Fastnet

Chapter Twenty-Four: 29 December Forenoon Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Twenty-Five: 29 December, Afternoon Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Twenty-Six: 29 December, Last Dog Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Twenty-Seven: 29 & 30 December, First Watch and Middle Watch

Chapter Twenty-Eight: 30 December, Morning Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Twenty-Nine: 30 December, The Forenoon Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Thirty: 30 December, Afternoon Watch and First Dog Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Thirty-One: 31 December, Afternoon Watch, The Western Approaches

Chapter Thirty-Two: 31 December, Midnight, Fastnet Rock

Chapter Thirty-Three: 1 January 1944, Middle Watch and Morning Watch, Irish Waters

Chapter Thirty-Four: 1 January, Morning Watch, Cobh Harbour

Postscript

Prologue

I don’t often have that same dream, but there are nights when – although I’m now far older than even Myles Foley lived to be – memories come back that I’ve never told anyone about. How can you talk about that time without folk who didn’t live through it making a fuss that blows what we did out of proportion? For the likes of us, there weren’t too many options for knocking out a living. My crewmates were ordinary seafarers – no heroics or histrionics. Just banter and slagging and ducking and diving, with a necessary sideline in small-time smuggling, born from the knowledge that shipping companies would dock whatever wages the sailors’ families received from the exact moment a torpedo shattered their ship’s hull or a Luftwaffe pilot dropped bombs on Irishmen bereft of uniforms or weapons, huddled in a tiny wheelhouse.

They were not at war with anyone – they just had to sail into the midst of everyone else’s war. I was only a scared greenhorn that they all took under their wing in their own unassuming fashion. Some days now, when I sit alone, with only the Health Board’s emergency pendant around my neck for company, I lose track of the decades that have passed. Why then is that old dream still able to ambush me with its palpable sense of terror? It makes no difference that I’ve survived to the age of eighty-eight, or whatever age I am now; all it takes is that first avalanche of drenching spray from a Biscay wave to cascade through my sleeping mind and I become a petrified fourteen-year-old cabin boy again.

I stagger across the deck as our small coaster tilts steeply downwards in the trough between huge waves – waves that this ship was never designed to withstand. Myles Foley is too exhausted to acknowledge my arrival beyond granting me a brief nod. The angle at which we ride the next wave is so severe that it feels like the ship may topple over, but this wave brings us within reach of more drowning men. One such man reaches out his right hand but Myles’s arm is too short, so I kneel to proffer my outstretched hand instead. A gash across the man’s forehead is clotted with blood. His eyes are bloodshot. His face, ravaged by cold, has two days’ stubble. But the brass buttons on his midnight-blue jacket display the insignia of a Nazi officer. As the Kerlogue rises in the swell of the oncoming wave, I miss his fingers by inches and he disappears from sight.

Myles Foley glares at me. ‘You could have reached him.’

‘I tried to rescue the Nazi murderer,’ I shout back, shocked by my guilty thrill of revenge.

The old man grips my soaked jumper. ‘You didn’t try hard enough. Before his ship sank he was a Nazi. Now he’s a drowning sailor. Out here, we’re all sailors. Your father and grandfather understood that about the sea. Are you going to disgrace their memory?’

The brutal force of the next wave hits us, smashing against the gunnel and spraying the deck with icy water. It soaks through our clothes, almost knocking us off our feet.

‘These sailors murdered my father.’

‘They followed orders,’ Myles Foley says. ‘If they hadn’t, they’d have been put up against a wall and shot.’

‘And you want me to follow your orders, is it?’ I am so overwhelmed I can barely comprehend what is right or wrong any more.

The ship tilts steeply before the next wave. The German officer resurfaces, his face bleeding even more profusely, having obviously been bashed against the ship’s side. Myles Foley leans over the gunnel, trying to reach him. ‘I don’t give orders,’ the old man snaps. ‘I’m not following orders either: I’m following my conscience and my conscience tells me to haul this poor bastard out.’

Part One

THE VOYAGE OUT

Chapter One

14 December 1943, the Wexford quays

The sea had claimed another victim. I knew this from the ambulance parked beside one of the small fishing trawlers moored on the Wexford quay, and from the sober demeanour of the fishermen on deck, standing around the sheet of tarpaulin with which they had covered the face of the man when transporting him back to Wexford. Barely a week passed without a Wexford trawlerman retrieving some grim souvenir of the war in Europe: shattered planks from a smashed lifeboat; lifebuoys bearing the name of a missing ship; a sailor’s hat bobbing on the waves with only a coloured ribbon to identify the nationality of the young man who had once worn it. Kilmore Quay and Arklow trawler crews had grown accustomed to hauling in lifeless bodies of sailors or airmen. Whether or not these victims were from the Allied or Axis side, the fishermen solemnly knelt in the same way on deck to recite a decade of the Rosary for the dead men’s souls before covering their faces with tarpaulin, treating them with the due respect that seafarers afforded to any fellow mariner.

A surge of desperate hope made me want to walk close to the trawler so I could peer over at the body. But Mr Tierney’s protective hand landed on my shoulder.

‘It’s been nine months, Jack,’ he said quietly, steering me away from the trawler and towards our intended destination.

‘I still want to see,’ I replied.

‘Trust me, you don’t.’ He blessed himself. ‘When some poor sod drowns out there and finally resurfaces, the sea will have done things to his face that nobody should have to witness. Say a prayer and pass on, Jack. Besides, wherever the trawler found him, it was a long way from Biscay. Only a proper eejit would venture into the Bay of Biscay on a rust bucket as small as them trawlers.’

My neighbour became quiet then, realising the grim irony of his words. Our eyes were drawn to the boat moored at the end of the quay. The Kerlogue was barely bigger than the two trawlers tied up alongside it. When the fishermen handed over this latest corpse to the authorities, they would make ready to sail with the tide, joining other Kilmore Quay boats in hunting for mackerel. But even such short expeditions, which barely strayed from sight of the Irish coastline, were not without danger. The Irish Sea could be broody: quick to change mood when storms brewed up. A fishing vessel might strike a mine that floated free from its moorings or find itself dragged beneath the waves if its nets became entangled with one of the hidden U-boats that often lurked in these waters: sharks patiently awaiting their next kill.

The corpse was being loaded onto a stretcher and carried up the gangplank. I turned my face away, comforted by Mr Tierney’s hand on my shoulder. I didn’t want to think about dead bodies being recovered from the waves. It reignited too many memories of a body never found; a sailor still officially listed as missing, though by now even my mother had accepted that my father was dead. As the ambulance prepared to move off, the fishermen bustled about at various tasks, needing to shout to be heard above the raucous scavenging seagulls. They already wished to disassociate themselves from the horror of what they had retrieved from the waves and distract themselves from the dangers that might lie ahead. But these fishermen would likely encounter little menace this evening and would land their catch safely. In two weeks’ time they would enjoy Christmas with their families – a better Christmas than many hungry families in Wexford would know. The tiny ship we were walking towards would be undertaking a more hazardous voyage, right into the wilds of Biscay. If not sunk by U-boats and capsized by storms, it would dock at Christmas in the distant port of Lisbon. My father had often described Lisbon, but I could barely imagine such a metropolis of teeming streets and steep laneways bustling with life.

Allied merchant ships sailed in blacked-out convoys, accompanied fore and aft by armed battleships to offer protection. But the MV Kerlogue would sail for Portugal utterly alone, lit up at night in the hope that the Luftwaffe would recognise its Irish flag and respect its neutrality. The fact that the Wexford Steamship Company was reduced to dispatching this patched-up vessel – just a hundred and forty-two feet in length – on such a voyage showed how often aircrews and U-boat captains felt inclined to use solitary Irish vessels for target practice when they encountered them, alone and defenceless, at sea.

My apprehension grew with every step we took. It would require all my courage to embark on this voyage if the Captain could be persuaded to employ me. I would need to gain my sea legs, overcome my fears and learn to share a cabin with men three times my age. But before facing such difficulties, I had to overcome a more pressing obstacle: I needed to become a convincing liar. My neighbour, who lived three doors down from us on Green Street, lifted his hand from my shoulder, indicating that we should walk like two adults. Mr Tierney was Second Engineer on the Kerlogue. Only his wife used his proper name of Maurice; every other adult in Wexford called him Mossy. As we reached the narrow gangplank he paused to look at me, as if this was the stupidest idea either of us had ever dreamed up.

‘Mother of God, Jack,’ he exclaimed. ‘When was your poor mother last able to put a proper feed inside you?’

‘I’m not so scrawny.’ I was too scared to feel insulted. ‘Everyone says I’m tall for fourteen.’

Mr Tierney threw his eyes to heaven. Red blotches around his nose betrayed how he had spent much of his shore leave holding up bar counters. ‘This isn’t a competition to find the tallest fourteen-year-old in Wexford,’ he said. ‘This is about whether you can pass yourself off to an experienced sea captain as being old enough to sign on for a voyage like this. Now, what age are you?’

‘You know my age, Mr Tierney. Didn’t your wife help to deliver me?’

He leaned down. ‘Listen good to me, Jack Roche: that’s the last time you ever call me Mr Tierney. From here on, my name is Mossy. What is it?’

‘It’s Mossy, Mr Tierney.’

‘Mother of Christ, grant me patience.’ He shook his head. ‘And what age are you?’

‘Sixteen on my last birthday, Mossy.’

‘Remember that. It’s the lie I told the new captain and it’s more than my job is worth to lie to him.’ His voice softened. ‘I’ve promised your mother I’ll mind you if the Skipper is daft enough to sign you on. But I can’t be like a father on board. Your poor father was lost on this same route. Sailing to Lisbon won’t be an easy voyage for you.’

‘Was there ever any easy voyage for him?’ I asked. ‘Or for you, since Hitler started this slaughter?’

Mr Tierney nodded. ‘The sea is no easy life, but what else am I going to do?’ He stared past the Kerlogue towards the mouth of the River Slaney. ‘The sea is in my blood, Jack. When you’re a breadwinner like me with nine hungry mouths at home to feed, you duck and dive and do whatever it takes to put food on the table.’

‘And if you were forced to sit at home, watching your younger brothers and sister starve, wouldn’t you do the same thing, Mr Tierney?’

‘You’re at it again: calling me Mister Tierney.’

‘It’s hard to break the habit of a lifetime, Mossy.’

‘I know.’ His voice softened so that he sounded more like the kindly neighbour I knew – the one who never returned from a voyage without bags of boiled sweets to be shared out among every child on Green Street. ‘But when you go to sea, you leave your old life behind.’ I felt he wanted to ruffle my hair, but such a gesture of affection was out of place on the quayside. ‘Listen, Jack, I was rightly fond of your dad. Sean got me out of many a tight scrape in foreign ports when I was stupid enough to let drink run away with my tongue, or some Flash Harry wanted to relieve me of my wages. I’m fond of your mother too: a proper lady. But if Captain Donovan signs you up, you’ll be just another shipmate, you understand? Don’t come running to me. You must stand on your own two feet on a ship. It’s an unforgiving world. Sailors are hard men but generally fair: though being confined to a boat can make anyone ratty and ready to snap for any reason or none. Some men take to the sea like ducks to water, and yet I’ve seen it destroy other fellows. You’ll know seasickness and homesickness and storms when you’ll think you’ll never see land again. And they’re less dangerous than some bars in Portugal, full of girls happy to pluck every penny from your pocket. If you’re not careful, waking up with a hangover and an empty wallet will be the least of your problems: you’ll need injections in places that a man can’t even think about without wincing. And they’re only the everyday dangers before we mention the war.’

‘The Emergency,’ I corrected him. ‘In school Brother Dawson beat us with his strap if we called it the war. He ordered us to call it “The State of Emergency” because Ireland isn’t officially at war with anyone.’

Mr Tierney stared back towards the town, his voice tinged with unexpected bitterness. ‘Is Brother Dawson still alive? He was always fond of his leather strap.’

‘He still is,’ I said, silently recalling numerous beatings for not knowing an Irish verb, or more often for no reason at all.

‘Does he still sew sixpences into his strap to leave an imprint of the coins on your palms?’

I nodded. ‘He has such a temper you never know when he’s going to explode.’

‘Do you know something, Jack? I bet if you met Hitler’s Gestapo, they’d be the spitting image of Brother Dawson, only kinder.’

It wasn’t the quiet anger in Mr Tierney’s voice that shocked me; it was the residue of fear. I found it hard to imagine this sailor once cowering in a classroom while blows rained down on his skull. Mr Tierney spat with slow deliberateness on the quayside.

‘Brother Dawson can call it what he likes here in Wexford, where people need only worry about their weekly half-ounce ration of tea. But if the Skipper hires you, you’ll be sailing into the teeth of war. So tell me again, where have you spent the past six months, scrubbing pots and mastering the black art of porridge-making?’

‘In the kitchens of St Patrick’s Seminary, which I’ve never actually set foot in, helping their cook to prepare meals.’

‘And where is the glowing reference the College President wrote, calling you so highly skilled that you’re destined to become the head chef in Jammet’s Restaurant in Dublin?’

‘My mother put it away for safekeeping and she can’t find it.’

The one daily train from Rosslare to Dublin slowly shunted past us along the metal tracks set into the quay. We watched it go by, breathing in the billowing smoke that reeked from the damp turf the stoker was using to coax the engine forward. It was growing dark as I looked back at the cramped streets of my native town: medieval roads so narrow that two cars could barely pass each other. Not that you were likely to see two cars with the strict rationing of petrol. This honeycomb of shabby alleyways was the only world I had ever seen, apart from one day when I borrowed a bicycle to cycle the twenty-three miles to Enniscorthy town. In Enniscorthy I had tried to impress the local girls by loudly jangling metal washers in my pocket while swaggering around, hoping to create the impression of being weighed down by half crowns. Instead I was so poor that I had to stop at a roadside stream on my cycle home to slake my thirst and search for berries to take the edge off my savage hunger. It was daunting to leave a town where I knew everyone and everyone knew my seed and breed. Yet I couldn’t go home empty-handed. Mr Tierney was shaking his head, exasperated at our threadbare excuse, even though he had invented it in my mother’s kitchen last night.

‘If we don’t say that your mother lost the reference, we’d have to pretend the dog ate it,’ he said. ‘And when Captain Donovan takes one look at you he’ll know the poor woman can’t afford to feed her own children, never mind keep a dog.’ Mr Tierney glanced up the rickety gangplank as we reached the ship. ‘I often think drink is a terrible thing, Jack.’

‘Does Captain Donovan drink?’

Mr Tierney shook his head. ‘He doesn’t, that’s the terrible thing. Our best hope was to find a skipper so stocious that he wouldn’t even notice your presence until he sobered up, halfway across St George’s Channel. But Captain Donovan has never touched a drop, even after nearly losing his life on the Irish Oak when the Germans torpedoed it heading home with a cargo of phosphates last May. Before that he was master of the Lady Belle of Waterford when she got bombed off the Welsh coast. Let’s hope he doesn’t need to get lucky with the Nazis a third time. But that won’t be your concern. Unless he’s suddenly become a full-blown alcoholic, he’ll send you hurtling back down this gangplank like a stone from a catapult. I’ll be lucky not to get the sack for trying to foster off an infant on him.’

I looked back at the laneways that I never wanted to leave. A boy my own age, Pascal Brennan, came freewheeling down Charlotte Street after making deliveries on his butcher’s bicycle. I wanted Brennan to topple over the handlebars and smash his skull. For days I had fantasised about accidents occurring to him, ever since I watched from my bedroom as he called for Ellie Coady to bring her to the Cinema Palace in her best blue polka-dot dress. I knew they went there because I’d followed from a distance, knowing I hadn’t enough money to bring Ellie to any film. I had stood outside the Cinema Palace, unable to stop imagining what Pascal and Ellie might be doing in those dark seats until I was driven away by the jeers of other boys eyeing me from across the road. Walking home alone, I had felt like a pauper.

I never liked Pascal Brennan. In school he always sat behind me making snide comments, like he had been doing on my last day in school nine months ago. I didn’t know back then that it would be my last day, but that was the day when every woman in Green Street went into a state of terrified paralysis: the day when rumours reached Wexford that the radio station at Valentia Island could get no response to the frantic signals they kept sending to my father’s ship. On that night I had put away my school books, unable to concentrate on Irish nouns or worry about Brother Dawson’s dangerous mood swings because I didn’t know if my father would arrive home – as he often did when delayed on a stormy voyage – or if I suddenly had become the man of the house. Nothing was certain back then; there was no floating wreckage, no survivors found, no official confirmation – just a limbo of waiting in which our hopes slowly petered out. For a long time my mother never referred to my father as being dead. But two weeks after I had stopped going to school, I woke to find that my short trousers were gone from the chair beside the small bed that I shared with my brothers, Eamonn and Tony. My mother had placed my first pair of long trousers there during the night – an unspoken acknowledgement that I had left my childhood behind.

I would have given anything to have Pascal Brennan’s job. I would happily even become a telegram delivery boy – the worst job during any war because telegrams almost invariably brought bad news. But there was no shop or builders’ yard I hadn’t visited a dozen times to ask if any work was going. Every Wexford shopkeeper was sick of my face, and I was sick of the shame of needing to ask the same question when I already knew the answer. But I was even sicker of the famished look in the eyes of Eamonn and Tony and little Lily when I arrived home each evening with one hand as long and empty as the other. If I stayed in Wexford, all I was good for was scrounging scraps of firewood or cinders that rich folk dumped in their rubbish, or walking the cold streets until dusk, eyes scanning the footpath in case I spied a smouldering cigarette butt or a ha’penny dropped from a purse. December was no month to undertake a maiden voyage. But I would sooner wake up in the creaking hull of a ship being tossed about the Bay of Biscay than see my starved siblings try to comfort our mother during her first Christmas as a widow. At the very least I would be one less mouth to feed. These long trousers made me a man.

The gangplank was rickety, without a rope or handrail. Striding past Mr Tierney, I placed one foot on it before I lost whatever courage I could summon. ‘Do you know something, Mossy?’ I said. ‘You do more whinging that the seminarians I used to make breakfast for in St Patrick’s. I thought that listening to the bloody cook there moan in his kitchen was bad enough. But in my sixteen years on earth I’ve never known a greater windbag than you. Now are we going to stand here freezing or talk to this Skipper?’

I had never seen Mr Tierney stuck for words before. He was still standing on the quayside in shock when I stepped onto the deck. Then he scrambled up the wooden gangplank. I turned to face him, unsure if I would receive a slap for my impudence.

‘You’re Sean Roche’s son all right,’ he said. ‘Just do me one favour: don’t call Captain Donovan “Skipper”. Call him “Master” or “Captain” or “Sir”. If you don’t, I’ll be joining you in searching for a job down every back lane in Wexford.’

Chapter Two

14 December, the Wexford quays

When i gazed back from the ship’s deck, only a few feet of water separated me from the quay, but already the view of the town looked different from the small ship. The Kerlogue had been built in Holland five years ago for the Stafford family, who owned the Wexford Steamship Company. Yet the ship possessed a haphazard, mismatched feel. The weathered wheelhouse up on the raised forecastle deck seemed to belong to an older ship, but the amidships deck was brand new. It smelled of fresh paint because of the Irish tricolour that had recently been daubed across it to make its markings more visible from the air.

This neutral flag had proved to be no defence six weeks previously when two warplanes machine-gunned the Kerlogue en route to Lisbon from Port Talbot in Wales. The original deck was ripped asunder, its radio transmitter shot to pieces and the lifeboats left in smithereens. Mossy Tierney had spent his shore leave telling pub drinkers that he was convinced he would meet his maker when water started to flood his engine room. It was just by the grace of God that the main engine was not hit. This allowed the pumps to continue bailing out enough seawater to keep the ship afloat. But only after the Kerlogue abandoned its outward voyage and limped back to Ireland did the crew discover why the ship hadn’t sunk: the hold was so densely packed with Welsh coal that the shells – while destroying the deck – had become lodged in the coal. This prevented them from ripping open the hull. Markings on the shells had proven that, on this occasion at least, the attackers were not German but a Polish squadron of RAF Mosquito pilots who didn’t seem to mind attacking a non-combatant ship that was actually carrying British cargo at the time.

Even though the boat wasn’t completely destroyed, the Kerlogue’s original crew had not escaped unscathed from that attack. The Chief Officer was laid up with shrapnel wounds, one sailor was traipsing about Wexford on wooden crutches, while the cabin boy, although unhurt, had not even returned to collect his wages. It was his job I was after. I might have stood more chance if the master of the Kerlogue on the day of the attack, Captain Fortune, was still in charge. He was a skipper my father had sailed under and always talked of with respect. But Captain Fortune had spent that attack roving around the ship to ensure his crew’s safety; his bravery resulted in compound fractures to both of his legs. It was rumoured that he would never be able to walk unaided again or go back to sea.

Mr Tierney was nervous of the replacement skipper on the Kerlogue. As he opened a door in the forecastle buckhead and led the way down the steep ladder to a narrow passageway below deck, his personality changed. He grew more deferential with every step closer to the Captain’s cabin. I barely recognised my devil-may-care neighbour who generally ended his tales with a wink, as if he could hardly believe the mishaps that he experienced in foreign ports. Perhaps it was the low ceiling and poor lighting, but he looked smaller. He gave me one last despairing glance before knocking timidly on the Captain’s door. I had been too preoccupied with my worries to consider the risks to Mr Tierney’s job if this new captain took umbrage at his Second Engineer for trying to deceive him, but I could understand them now. A voice from within instructed us to enter. Mr Tierney opened the door and took a cautious step inside, beckoning me to follow. He didn’t want to venture too close to the Captain’s desk, but the cabin was so small that we were already on top of the man, who glanced up from the papers piled in front of him.

I had expected Captain Donovan to wear a gold-braided cap, like the ones you saw sea captains wear about the town. He was more casually dressed, but there was no mistaking the quiet authority he exuded. It was an earned authority that had no need to spill over into stern self-importance. Brother Dawson always needed to be the centre of attention. If a boy even glanced down at his copybook when Brother Dawson was talking, he would hear a swish of black robes, like the wings of a hawk bearing down on its prey, and feel that leather strap savagely strike his skull. But as Captain Donovan appraised me with a glance, I felt myself to be in the presence of a different type of authority. I’d always feared Brother Dawson for the pleasure he gained from assaulting anyone weaker than him, but I had never respected him like I immediately respected this man.

I knew nothing about Captain Donovan, beyond the fact that he had already survived two sinkings and was now taking charge of a ship with no earthly right to still be afloat. But I sensed at once that I could trust him with my life. I also knew that I could never fool him. I realised that Mr Tierney sensed this too from how he fidgeted awkwardly – a telltale sign whenever he was trying to bluff his way out of a situation he could no longer control.

‘This is the lad I mentioned, Captain,’ Mr Tierney began. ‘Young Jack Roche, Sir.’

Captain Donovan leaned back to survey us with a weary sigh. ‘I heard you were prone to exaggeration, Mossy, but “young” is an understatement.’ He addressed me directly. ‘Have you any experience at sea, Roche?’

‘He has great experience in the kitchens, Captain,’ Mr Tierney interjected. ‘He worked for the Cook in St Patrick’s Seminary. Show the Master that glowing reference from the College President, Jack.’

I felt so paralysed under the Captain’s stern gaze that Mr Tierney needed to nudge me before I spoke. ‘My mother put it somewhere for safekeeping, Master, and we can’t find it, Sir.’

A lesser man might have made a joke at our expense. But Captain Donovan seemed to respect that nobody showed up on a vessel about to undertake a dangerous voyage without good reason. I knew he had already decided not to employ me, but was affording me the courtesy of a proper interview.

‘How old are you, Roche?’

‘Sixteen on my last birthday, Sir.’

‘So your date of birth is …?’

‘May 17, 19 …’ I cursed myself and sensed Mr Tierney damn my slow wits. My hesitation only lasted a second, but was enough to confirm what Captain Donovan already knew. ‘ …1927, Sir.’

‘Get away home with you, Master Roche.’

‘If I could interject for the briefest second, Captain …’ Mr Tierney began. I didn’t know what desperate ploy my neighbour had up his sleeve, but a glance from Captain Donovan reduced the Second Engineer to silence. The man behind the desk looked at me directly. His tone was neither angry nor condescending. It was sympathetic, but firm.

‘Does your mother know you’re trying to sign on, when you’re so young you can barely wash behind your ears?’

‘She does, Sir.’

‘And does she know how often Irish ships get attacked? Every time we sail we need to get lucky. If U-boat commanders don’t respect our markings, nobody comes to our rescue. Do you understand this, Roche?

‘I do, Sir.’

‘This ship has only been tacked back together with a few prayers and a lick of paint. Did Mr Tierney not tell you this?’

‘He told half of Wexford, Sir.’

The Captain smiled for the first time. It made him look younger, as if he had momentarily forgotten the responsibilities of the forthcoming voyage. His countryman’s smile matched his soft Waterford accent. It was easier to imagine him leaning over a gate into a field on a summer’s evening than manning a ship’s wheel. ‘They’re the first true words you’ve spoken, Roche, and they’re only half true. Mossy told the other half of Wexford too, in public houses you’re too young to set foot inside.’

Mr Tierney shifted position with a defensive shrug. ‘I may as well spin the odd yarn, Captain, seeing as every time we set sail there’s a fair chance I’ll never get to tell another one. I enjoy a pint, but I’ve never missed a day’s work and no Captain has ever stamped anything less than VG in my Discharge Book when I sign off any ship. When we sail at dawn I’ll be present and sober, even if my stomach might need the sort of breakfast young Roche has been helping to serve up for the seminarians in St Patrick’s College.’

The Captain’s patience seemed on the verge of being tested. ‘That’s enough guff, Mossy,’ he said quietly. ‘I’ve paperwork to finish for the Staffords. When we catch the dawn tide, this lad will be safely tucked up in his bed.’ He picked up a pen before addressing me. ‘Go home, son. This ship is no place for children. Nobody’s saying you’re not brave, but nobody knows the meaning of fear until they’re at sea and U-boat surfaces and starts to circle them. Do you know how many Irish boats we’ve lost in this war?’

‘A goodly number, Sir.’

‘The Leukos off Donegal: eleven dead. The Kerry Head off Cape Clear: twelve dead. The Ardmore off the south coast: all twenty-four crew lost. The Isolda sunk within sight of Wexford: six dead. Eleven crew from the Clonlara, lost on the same treacherous stretch of the Atlantic where thirty-three souls from the Irish Pine now lie. The Kyleclare, sunk without trace last February: eighteen crewmen scattered on the ocean floor. I don’t know what tales Mossy filled your head with, but can you imagine such a death?’

‘I only know about the Kyleclare, Sir. Every night when I close my eyes I imagine bodies trapped in the wheelhouse. It’s all I think about, though I try to block out such thoughts.’ I could feel my cheeks burn and it felt odd to be confessing something to a stranger that I had never even told my mother. She had enough grief without the burden of my sorrow. But often at night, when I told Eamonn and Tony that I would sleep upside-down to give their heads more space on the pillow, in truth it was so that they wouldn’t see my tears when I cried silently, imagining my father’s corpse after months beneath the waves. Captain Donovan studied me carefully.

‘Why makes you think about the Kyleclare?’

‘My father was lost on it.’

The Captain rose and put out his hand to shake mine. ‘I’m truly sorry for your troubles. What was his name?’

‘Able Seaman Sean Roche, Sir.’

Captain Donovan nodded. ‘I never sailed with him, but I always heard his name mentioned with respect. How is your mother coping?’

‘She has good neighbours, Sir, Mr Tierney among them. I didn’t mean to get him into trouble. Good neighbours are all she has.’

‘She has a fine son.’

‘She has three sons and a daughter. My brothers are twelve and ten. Lily is only seven. The nuns wanted to take her but my mother won’t let them. I’m the man of the house now, Sir.’

He returned to his seat, shuffling papers to allow himself time to think. He looked up.

‘What’s your real age, Jack?’

I hesitated. ‘Fourteen and a bit, Sir.’

‘You seem a mature lad – God knows, you had to grow up quickly. But the sea has taken enough from your mother. Your father’s death is only another reason to order you back down that gangplank and away from danger.’

‘I’d sooner face any danger than walk home to face three famished faces looking up at me. I can’t bear that any more, Sir.’

‘You’re no use to your family dead, Jack.’ Captain Donovan’s voice was kind. ‘The priests in St Patrick’s surely pay you some pittance to work in their kitchens. Knowing your circumstances, they must let you bring home leftover food.’

‘I’ve never worked in a kitchen, Captain. Since my father died I’ve walked the streets seeking work. I know the Staffords only pay the National Maritime Board rate and that’s barely a pittance for a cabin boy. But Mr Tierney says the Irish government tops up the wages of every man willing to sail to Portugal by paying ten pounds a month danger money, regardless of whether you’re a captain or a cabin boy.’

‘They officially call it war-risk money,’ the Captain said. ‘It can nearly double an ordinary sailor’s wage. It would more than quadruple a cabin boy’s wages and shorten his life expectancy to twice that again, which explains why they’re right to call it war-risk money.’

‘I’ve good reasons at home why I should take that risk, Sir.’

My reply was respectful, but so stubborn that the atmosphere felt like a Mexican standoff. Then came the sudden sound of voices on the amidships deck, as two sets of footsteps clambered on board. The Kerlogue was so small that I could already smell their cigarette smoke. The Captain opened a drawer. He removed some sea charts and then found his leather wallet. He glanced at Mr Tierney.

‘Did the men hereabouts have a collection for Able Seaman Roche?’

‘As soon as we got word, Sir; or in poor Sean’s case, once we realised that we’d never receive word. We dug deep for his widow, but most of us were digging in empty pockets.’

Captain Donovan opened his wallet. Taking out a pound note, he placed it on his desk. ‘I was detained elsewhere in a lifeboat and never got to contribute. It was only sheer fluke that I got rescued and didn’t share his fate. Excuse the lateness of my contribution, and please send your mother my condolences.’

What he offered was extraordinarily generous. A pound would make a big difference to my mother at Christmas. Some men who went to England were rumoured to earn up to seven pounds a week in the factories that produced munitions around the clock. But in Ireland there were farm labourers who barely got fifteen shillings a week, which was more than Pascal Brennan earned for cycling his butcher’s bicycle in all kinds of weather. If I returned home tonight, having used our ration books to get fresh bread and potatoes, Eamonn and Tony and Lily would be more awestruck than if the three wise men arrived with gold, myrrh and frankincense. I knew the depth of their hunger because I shared it. But I couldn’t take his money. My mother scrubbed floors in the local doctor’s house. She took in washing and I often saw her sit up in the half-light, darning away despite her fingers being almost too numb with cold to work. The one thing she didn’t take in was charity. Besides, while the Captain’s generosity might help us through Christmas, in January I would be back walking the cold streets and searching for cinders in rubbish tips.

‘I appreciate your generosity,’ I said. ‘But I can’t be taking your money.’

Mr Tierney stared at me as if I was an inmate escaped from the County Asylum. He sounded more shocked than if he’d heard me give cheek to a cardinal. ‘If the Master is good enough to offer you …’

‘I didn’t cross this gangplank looking for charity.’ I cut across my neighbour’s protestations. The two crew members had descended the ladder. I sensed them loitering in the passageway, their curiosity stoked by our voices. Captain Donovan summoned them in. I recognised the ship’s cook from seeing him around the town. Beside him a ferret-like man in a cloth cap crowded in through the doorway. There was barely space for us all in the cabin.

‘The last provisions are loaded, Captain,’ the Cook said. ‘Ernie Grogan gave me a hand to carry them up from the town.’

The ferret-faced man nodded. His accent was pure Cockney. ‘If they’re as heavy in my stomach as they were in that sack I won’t complain.’

‘Your cabin boy never signed back on after the RAF attack?’ Captain Donovan asked.

The Cook laughed. ‘That scut? The minute we docked, he took off like a scalded cat.’

Ernie Grogan chortled. ‘If that dustbin lid ever visits the cinema he’ll get barred for doing a jimmy riddle on his seat every time there’s an explosion on screen.’

‘Are you seeking a new cabin boy?’ Captain Donovan asked the Cook. ‘I’ve a lad here who can’t cook and was never at sea.’

The Cook inspected me like a farmer examining a cow at a mart. His eyes stopped when they reached my face. ‘You’re a Roche, whoever you are. Are you anything to the late Sean Roche?’

‘I’m his eldest son.’

The Cook nodded. ‘The Reader Roche we called him: he always had his nose in a book. I sailed with him often. You have his untidy mop of hair and your granddad’s eyes. The crew had a collection for poor Sean. I hope your mother got it.’

‘She was deeply grateful.’

‘I’d say that’s all she got. Ireland’s a cold country for a widow.’

‘How come you took the Cook’s money, yet you won’t take mine?’ the Captain asked. ‘It’s not charity when a seafarer helps a drowned shipmate’s family; it’s an unwritten law of the sea.’

‘No disrespect, Sir, but you were never his shipmate.’

From Mr Tierney’s intake of breath and the terse silence of the Cook and Mr Grogan, I sensed how all three felt that I had crossed a line. Even Captain Donovan seemed taken aback. ‘God grant me patience,’ he muttered. ‘Are you applying to be a cabin boy or to be a Jesuit, splitting hairs about the meaning of words? What do I do with a stubborn mule like you, Roche?’

‘Give me a job as a cabin boy, Sir.’

The Captain glanced at the Cook, soliciting his opinion. The Cook addressed me. ‘Did Sean tell you never to go to sea?’

‘ ‘‘Get a shop job,” he’d always tell me. “Sweep the streets maybe, but don’t waste your life on the ocean”.’

The Cook nodded. ‘I can hear Sean saying that. It’s what my father told me and your granddad told Sean. Not that we paid them any heed because there’s no sailor to match a Wexford sailor. That’s why Wexford schools teach map-reading while Wicklow schools only teach the poor eejits how to herd sheep without falling over. I sailed with your granddad when I was a boy. He took me under his wing and introduced me to bowline knots, woodbines and cheap Spanish brandy.’ He addressed the Captain. ‘If you sign him on, Sir, I’ll knock him into shape. The sea is in his blood. We’ll have to say a Novena that cooking comes as natural to him.’

‘Mossy was trying to persuade me that the boy singlehandedly ran the kitchens in St Patrick’s College,’ the Captain said, amused.

‘They need to close the churches when Mossy Tierney steps on dry land.’ Ernie Grogan interjected. ‘That ducker and diver would say Mass if he got the chance.’

‘What would you know about Mass, and you a Protestant?’ Mr Tierney replied. ‘The only time you ever enter a church is to test the steel chain attached to the poor box.’

‘That’s enough from you both,’ Captain Donovan said. He looked at me. ‘Our Chief Engineer, Mr Grogan, is Mossy’s superior. Thankfully there’s a steel-plated bulkhead between me and the engine room so I can’t hear their endless bickering. I may employ you simply to keep the peace between them.’

The Cook put a hand on my shoulder. ‘I’ll work him hard and teach him all there is to know about cooking. He’d have learnt nothing in St Patrick’s. Those seminarians all have cranky, constipated looks. Whoever makes their porridge burns the pot to blazes.’ The Cook looked at the Skipper. ‘Will you give him a chance, Sir?’

Captain Donovan said nothing. I sensed every man present holding his breath. Then he opened his wallet and added two red ten shilling notes to the pound note on his desk. ‘This is not charity any more. Some sailors call it drawing a dead horse, but the proper term is an ‘Advance Note’ – some of your war-risk money paid up front after you sign the ship’s articles. I’ll have a contract for you at dawn. You’ll need a Seaman’s Identity Card with a photograph on it stamped by the police.’

‘Leave that to me,’ Mr Tierney said. ‘A garda sergeant owes me a favour.’

The Captain pushed the banknotes towards me. ‘If you sign up, you’ll earn every penny. Give most of this to your mother to tide her over Christmas and buy yourself a donkey’s breakfast from the balance.’

I looked at him, puzzled. ‘What’s a donkey’s breakfast, Sir?’

Ernie Grogan addressed me for the first time. ‘A sack of straw you throw on top of your bunk to have something soft to sleep on. There’s no nicer feeling than dumping that blasted sack overboard after a long voyage and knowing that every flea inside it that’s been biting you will soon be brown bread.’ He wiped his hand on his coat and shook mine. ‘Welcome on board, my old mate.’

‘He’s not on board yet,’ Captain Donovan said. ‘Sleep on your decision. If you can sleep, Jack. Be here at dawn unless you change your mind. We’ll see how you fare on your maiden voyage before deciding if we keep you on. Hopefully your mother has a spare blanket of your father’s to save you the expense of a new one.’ He picked up his pen as a signal for us to leave, and then gave me one last look. ‘I’ll not be annoyed if you don’t show up. I’ll be partly relieved. But don’t consider this Advance Note as charity if you decide against sailing. See it as a loan. A betting man would give good odds you’ll never need to pay it back if a U-boat stumbles across the Kerlogue between here and Lisbon.’

Chapter Three

15 December, Wexford town

I tried not to wake my mother as I silently got dressed the next morning. The house and the town were still in darkness. Mr Tierney had offered to buy my sack of straw and leave it on the ship. My bag was feather-light, even after I tied a rolled-up old blanket of my father’s to it. I had no fear of disturbing my brothers. Once they fell asleep in an untidy tussle of limbs, it would take a Luftwaffe air raid or a hell-and-damnation sermon to wake them.