Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

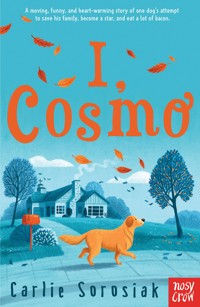

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

The story of one dog's attempt to save his family, become a star, and eat a lot of bacon. Cosmo's family is falling apart. And it's up to Cosmo to keep them together. He knows exactly what to do. There's only one problem. Cosmo is a Golden Retriever. Wise, funny, and filled with warmth and heart, this is Charlotte's Web meets Little Miss Sunshine: a moving, beautiful story, with a wonderfully unique hero, from an incredible new voice in middle grade fiction - perfect for fans of Rebecca Stead and Kate DiCamillo. "This gem has all the warmth and joy of Homeward Bound, and is making me want to get a golden retriever immediately." - Catherine Doyle, author of The Storm Keeper's Island "Cosmo's narration combines wit, heart, stubbornness, and a grouchy dignity, all ably tugging at funny bones and heartstrings alike." - Kirkus (starred review) "I adored this, a genuine feel-good delight with the most lovable animal narrator I've read in ages." - Fiona Noble, The Bookseller "Like any good dog, Cosmo is so funny, friendly, and loyal that he quickly became a dear friend, so much so that when I finished reading the book, I missed hearing his voice and picturing his shaggy face. Come back, Cosmo!" - Jim Gorant, author of the New York Times bestseller The Lost Dogs

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 266

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To all the dogs I’ve ever loved, and very much still do, especially Ralphie, Sally, Dany, Buddy, Faith, Chloe, Mary Jane, and Oscar.

C.S.

“How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

W. B. Yeats

1

This year I am a turtle. I do not want to be a turtle.

“His tail’s between his legs,” Max notices, cocking his head. Worry spreads across his wonderful face. “You think the hat’s too tight?”

We are on the porch, and the strange pumpkin is smiling at us – the one Max carved last week, scooping out its guts. I ate the seeds, even though he told me, No, Cosmo, no. I find it difficult to stop myself when something smells so interesting and so new.

Max’s father, whose name is Dad, readjusts the turtle vest on my back. “Nah, he’s fine. He loves it! Look at him!”

This is one of those times – those infinite times – when I wish my tongue did not loll in my mouth. Because I would say, in perfect human language, that turtles are inferior creatures who cannot manage to cross roads, and I have crossed many roads, off-leash, by myself. This costume is an embarrassment.

At a loss, I roll gently on to my back, kicking my legs in the air. An ache creaks down my spine; I am not young like I used to be. But hopefully Max will understand the subtle meaning in my gesture.

“Dad, I really think he doesn’t like it.”

Yes, Max! Yes!

Scratching the fur on his chin, Dad says to me, “OK, OK, no hat, but you’ve gotta keep the shell.”

And just like that, a small victory.

Emmaline bursts on to the porch then. She is all energy. She glows. “Cosmooooo.” Her little hands ruffle my ears, and it reminds me why I am a turtle in the first place – because Emmaline picked it out. Because it made her happy. I’ve long accepted that this is one of my roles.

Max grabs Emmaline’s hand and spins her around, like they’re dancing. Her purple superhero cape twirls with the movement. Last week, I helped Mom make the costume: guarding the fabric, keeping watch by her feet, and every once in a while, she held up her progress and asked me, “Whaddya think, Cosmo?”

A wonder, I told her with my eyes. It is a wonder.

“Shouldn’t we wait for Mom?” Max asks. He is dressed in dark colours, patches on his shirt, and I suppose he is a cow or a giraffe, although I do not like thinking of him as either. Giraffes are remarkably stupid creatures, and Max is very, very smart. He can speak three languages, build model rockets, and fold his tongue into a four-leaf clover. He can even unscrew the lids off peanut butter jars. I’d like to see a giraffe do that.

Dad replies, “She’s late. Don’t want to miss all the good candy.”

Max says, “I just think—”

But Dad cuts him off with “Ready, Freddy,” which he is fond of saying, despite the fact that Max is called Max. After a pause, the four of us set off into the bluish night. Our house is a one-storey brick structure with plenty of grass and a swing set that only Emmaline uses now. Paper lanterns line the driveway, lighting up the cul-de-sac.

The fur on the back of my neck begins to rise.

Halloween is the worst night of the year. If you disagree, please take a moment to consider my logic:

1. Most Halloween candy is chocolate. My fourth Halloween, I consumed six miniature Hershey’s bars and was immediately rushed to the emergency vet, where I spent four hours with an incredible tummy ache.

2. Young humans jump out from behind bushes and yell, “Boo!” This is confusing. One of my best friends, a German short-haired pointer, is named Boo.

3. Clowns.

4. Golden retrievers, like myself, are too dignified for costumes. I am not entirely opposed to raincoats if the occasion arises, but there is a line. For example, Mom bought me a cat costume once, and I have yet to wholly recover from the trauma.

5. The sheepdog is let loose.

Allow me to elaborate on this fifth point. I have never had an appetite for confrontation – not even when I was a puppy. But I make an exception for the sheepdog.

Five Halloweens ago, on a night just like this, Max and I approached a white-shingled house at the end of the street. A big, blocky van idled by the mailbox, and a roast-chicken smell wafted from two open windows. I knew immediately that we had new neighbours – the old neighbours were strictly beef-eaters. An eerie quietness settled over the street, a dark cloud moving to block the moon. So quick that I did not even see it coming, the sheepdog emerged from behind a massive oak tree in their front yard. It was wearing an ominous pink tutu and fairy wings, its grey-and-white fur standing on end.

My immediate reaction was empathy – hadn’t we both succumbed to the same costumed fate? I began to trot over in my bunny outfit, intent on bowing in commiseration, and then welcoming it to the neighbourhood with a friendly sniff of its butt. What happened next was not friendly. I have never seen anything like it in my thirteen years.

The sheepdog bared its teeth, a menacing snarl directed straight at me… And I swear its eyes glowed red.

I was horrified.

There are few things that truly frighten me: trips in the back of pickup trucks, the vacuum (the sound, the sharp smell, the way things disappear inside it), and anytime Max or Emmaline are in danger. That night, as the sheepdog cast a final red-eyed glance in my direction, its ears back and incisors gleaming, I added one more thing to the list.

Previously, I took great pride in knowing the name of every dog in the neighbourhood. Names mean something: they are how we present ourselves to the world. Take “Cosmo”, for instance. Mom once explained that Cosmo means “of the universe”; then she pointed up at the sky, and Max got out his long metal tube that allows you to see the stars up close. It made me feel important, like I was part of something bigger than myself. I have intense sympathy for dogs named “Muffin” or “Scooby” or “Biscuit”. How can they hold their tails up? With the sheepdog, I chose to simply call it by its breed. I chose not to name my fear.

The sheepdog is normally trapped behind a wooden fence, but each Halloween it is let loose to greet the trick-or-treaters.

And I must face it.

Emmaline skips ahead of us, her light-up sneakers casting shadows on the sidewalk. I trot alongside Max, my leash limp in his hand. The evening is brisk but mild – “sweater weather”, humans call it. A breeze shivers through my fur, carrying with it a variety of wonderful scents. Apple pie! Squirrels! Rotten leaves! Momentarily, I forget about the sheepdog and my embarrassing costume, letting myself revel in the smells, my tail whipping through the air. I press my nose to the ground, and almost immediately – what’s this? Candy corn!

“Cosmo,” Max says, gently shaking my leash. “Leave it. It’ll give you a bad stomach.”

But I’m so overcome by the candy corn’s smell, by its lovely symmetry against the pavement, that I make a second attempt. My tongue has almost scraped it from the ground when I’m pulled in another direction.

Max glances down at me, picking up the pace. “Sorry, Cosmo. I’ll give you a cookie when we get home, OK?”

I trust that Max will keep his word, so I lower my head and trail him down a brick path, where two women are perched on a stoop, garbed in black dresses with pointy hats. Behind the glass front door, a Maltese named Cricket yaps itself hoarse. My patience for small breeds is limited. According to the Discovery Channel, which I watch frequently when Max and Emmaline are at school, all dogs are descendants of wolves. But looking at Cricket, who barely makes it to my knees, I question the truth of that research.

“Awww,” one of the women coos, dropping a lollipop in Emmaline’s plastic pumpkin. “What do we have here? A superhero and a giraffe?”

A giraffe! I knew it!

Max stares at his toes – and I nudge the palm of his hand, digging my nose inside it; I do this to remind him that I am here. Around some humans, Max refuses to speak, and his heartbeat pounds in his fingers.

“Oh my goodness,” the second woman says, spotting me. “And a turtle! Cosmo, you’re a turtle! Come here, boy, come here.” She pats her lap, as if I’m supposed to jump on top of it. Apparently she has not heard about my arthritis. The last few years, my joints have got sore: a burning ache that I lick and lick. Still, out of a sense of neighbourly duty, I partially oblige her, even though I feel – just slightly – like she is mocking me. Her fingers smell of those miniature sausages Mom wraps in pastry dough and pops in the oven on holidays. Last Christmas, I devoured seven when Dad left his tray unattended. I can still recall the way the sausages felt sliding down my throat: warm, salty, oblong. It was the fourth best day of my life.

“Getting many trick-or-treaters this year?” Dad asks the women, sticking his hands in the pockets of his jeans.

“Oh, loads!” the one scratching my ears answers. “We’ve had lots of ghosts, a few pirates, an avocado … and the night is still young!”

The expression doesn’t add up. How can a night be young?

Old. Young. Usually, I am good with ages. Emmaline is five. Max is twelve. And I am thirteen – eighty-two in human years. In our neighbourhood, there is only one dog older than me: a yellow Labrador named Peter, who manages with the help of a cart strapped to his hindquarters. I have heard rumours of the existence of doggy diapers, of pills that artificially prolong your life. I am uninterested in those options. But I also know that, as the eldest member of my family, I need to be there for them as long as I can, any way I can.

Good thing I have a whole lot of life left in me.

We depart from the stoop, kids giggling in the street, parents chasing them down with flashlights, and we repeat the process dozens of times: approaching the neighbours, begging for food. I’ve always found this interesting. When I beg underneath the dining-room table, my nose wedged between knees, the results vary. Sometimes Max passes me a corner of his sandwich, lets me lick the meaty juices from his plate. Other times, Dad scolds me with “No, out”, and I’m banished to the living room, where I chew self-pityingly on a rope toy. The rules are different for humans.

I am beginning to slow down, my breath more laboured, when – we’re here. In front of the sheepdog’s house. My hackles stand up.

But where is the demon dog? I can’t see it! I can’t even smell it!

Max answers my whimpers. “What’s wrong, Cosmo?”

What’s wrong? The giraffe costume must be infecting him with its horrible giraffe power. Surely it’s obvious: the sheepdog is plotting something!

Emmaline sucks in her breath and lets it all out. “I’m tired, Daddy.” Her cape drags along the sidewalk, crisp leaves stuck to the bottom.

“You wanna go home?” Dad asks. “Your buckets are pretty full.”

The sheepdog! Why is no one concerned about the sheepdog?

Max says, “I’m up for whatever Emmaline wants. I’ve got enough candy for, like, a year.”

What’s this? The three of them are turning to head for home. No! I plant my paws and refuse to budge. If the sheepdog is hatching a plan, it must be stopped.

Max tugs at my leash. “Cosmo, come on, please?”

No.

Dad says, “Cosmo, let’s go.”

No.

Emmaline rests her hands on my back. “Cosmooooo.”

Eventually Dad takes the leash and pulls, slowly but hard, and I’m forced away from the sheepdog’s house, the windows glowing amber in the autumn night. Wait. Wait! In the final seconds, directly on its yard, I lift my leg and release a stream of urine. As a signal. As a warning. I’m on to you.

I depart, on edge but mostly satisfied.

Back at our house, as promised, I get a cookie, and Emmaline and Max divide up their candy on the living-room floor: piles for lollipops, piles for chocolate, piles for the candy no one likes. “Yuck,” Emmaline says, tossing a box of raisins to the side. Her black curls whip back and forth as she shakes her head. “Yuck, yuck, yuck.”

I observe from my position on the couch, which is difficult to climb on to nowadays. Sometimes it takes several tries, several embarrassing topples. A long time ago, I was not allowed on furniture, which made little sense. Wasn’t my dog bed constructed of similar materials? Why was I allowed on one, but forbidden to lie on the other? Eventually, Dad gave up his couch crusade, and the cushions began to form around the shape of my body. I’ve learned that perseverance is a powerful thing.

The TV is on in the background. A talking black cat parades across the screen. Why do cats always get to speak on TV? Where are all the talking dogs? The dog in the movie Up speaks, but only with a translation collar. Lassie, the most famous TV dog of all time, just barks. I’m puzzling over the inequity when the back door slams. It is incredibly loud, purposeful. And then the voices begin.

Mom growls in the kitchen, “David, did you really?”

“What?” Dad says.

“You were supposed to wait for me! I told you I’d be working late! I didn’t even get to see the kids in their costumes…”

“They’re still in their costumes.”

“I mean out in the neighbourhood, trick-or-treating. I was supposed to go with you, remember? Or did you conveniently just forget?”

“That’s unfair. You were late.”

Mom throws up her hands. “I told you I was going to be late. That’s why I asked you to wait for me!”

I don’t like the way they’re speaking to each other. From the couch I give them a disapproving look. Can’t they see Max and Emmaline are happy, that their voices are ruining it? Emmaline slowly crumples to the side, laying her head on the carpet next to the raisins, while Max tugs his knees to his chest.

“Let’s just…” Dad says. “Let’s just get a picture, OK? That’s what you want, right?”

“What I want? You don’t care about what I want.”

But we take the picture anyway, the five of us crowded by the fireplace, smiling at a small camera. After a few moments, a flash fills the room, and Max says quickly, “OK, I guess I’m going to bed.”

Mom glances at him hopefully. “You don’t want to stay up a little bit? Watch Halloweentown with me?”

“I’m … I’m kinda tired.”

“Oh,” Mom says. “Sure, OK. Goodnight, sweetie.”

“Night.” He kisses Emmaline on the forehead. “Night, Em.”

As I do every evening, I follow Max into his bedroom. Posters of the night sky stare down at us from the walls. There’s also a large picture of Guy Bluford, the first African American in space. He flew four shuttle missions beginning in the early 1980s. I know this because Max shares things with me; being an astronaut is his dream.

Curling at the edge of his bed, I rest my head on my paws. Uneasiness crawls through me. Something is wrong. I’ve heard that dogs can sense hurricanes and tsunamis when they’re still miles offshore. This is similar.

Max closes the door – and immediately bursts into tears.

Crying?

Max rarely cries. Only when he’s fallen off his bike, or slipped on a patch of ice, or—

I don’t have time to think about it. I just react, standing as quickly as I can, rushing towards him as his back slides against the wall, as he folds to the floor. I lick his face. His ears. His fingers. I wedge my head between his hands and rest my muzzle on his shoulder. Shaking, his arms wrap round me, and he whispers directly into my ear, “Never leave me, Cosmo. Never leave me, OK?”

Why would I leave? Why would I ever leave Max?

I nuzzle him deeper in response.

And we stay like that for a long, long time.

2

I was born a puppy, thirteen years ago in a garage near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. I do not recall much about my early life, except cardboard boxes under my paws and the whines of my siblings, who always nudged me away from the food dish.

I also remember the day I met Mom and Dad. Back then, they were called Zora and David Walker.

It was one of those pale blue mornings in early spring, and the man who changed the cardboard boxes leaned into our pen, pointing a long finger at my front paws. “See here? He’s pigeon-toed. I reckon all his sisters are show-dog quality, but him, I’ll go half price.”

Zora peeked in. She had a round head of black curls and her eyes were kind. She smelled of things I could not yet name but would later identify as rosemary soap and apples.

I licked the back of her hand, half to say hello, half to determine its taste.

“He’s so sweet,” she cooed.

“You sure you don’t want one of the females?” David asked. I looked up at him for the first time and immediately pegged him as part spaniel, fur floppy and brown against his white forehead. What he was crossed with, I did not know, but it was a breed that tapered his nose at the sides.

“I’m sure,” Zora said.

I went home with them that day, to a ranch-style house in a quiet North Carolina neighbourhood. Out of sheer nervousness I threw up twice in the four-hour drive, and Zora cleaned me in the bathtub with warm water and that rosemary soap, whispering, Little Cosmo, everything’s all right. And it was. Our first year was punctuated with cuddling Zora as her stomach grew bigger, learning a handful of commands, and appreciating the difference between carpet and grass – specifically, which was an appropriate place to relieve myself.

It wasn’t long before Max arrived.

Three days after the delivery, David cradled Max in his arms and folded himself on to the living-room floor, right next to me. “You’re a big brother now, Cosmo. You up to the job?”

Was I?

I sniffed Max’s tiny face, perplexed. I had perhaps naively assumed that humans were born with a full body of fur and, as they aged, shed their outer layer. But – except for the wisps on his head – Max’s brown skin was smooth and bare.

A big brother. The enormity of the responsibility hit me as Max slowly opened his eyes, and they were glassy and full of something that I can only describe as admiration. He was perfect. I loved him instantly.

Yes. Yes, I was up to it.

I conveyed this with a short but meaningful woof. David took one hand from Max and smoothed the crinkled fur on the back of my neck, something he had never really done. I saw it as a pact between us. I would protect Max, and David would love me in return. In those moments, we became a family.

There is a word I’ve learned in the twelve years since: doggedly. It means “with persistence and full effort”. Humans attribute this to a dog’s stubbornness – our refusal to give up chewy sticks, the way we freeze in the doorway when it rains. But really it’s the way we love, with our whole hearts, no matter the circumstance.

I vowed to protect Max – and my family – doggedly, for the rest of my life.

3

The morning after Halloween, Max is awake early. I hear him throw off the covers and tiptoe down the hall to the bathroom, water rushing through pipes.

As a young dog, I loved mornings. I was a kid at Christmas. I would spring up at the sound of movement, lick sleeping faces, bark at the back door – out, out, out! And finally Dad would succumb to my will, grumbling, “OK, Cosmo, OK,” and we’d romp through the dewy grass, watching the sun split sideways over the neighbourhood. Now I am slower. Even my bones ache today.

I get up carefully, stretching my back legs, and take a few measured steps off my plush bed, which Mom has sprayed with a flowery mist. Humans are obsessive about animal smells – always trying to mask them with other scents that will never smell as rich or as good. My theory is this: because humans relieve themselves in bathrooms instead of in the great outdoors, they have little urine left to mark their territory. Flower sprays are a poor substitute.

More sounds: the toilet flushing, an alarm buzzing, Mom murmuring something.

Food. The thought does strike me. I pride myself on seldom succumbing to baser urges, but I find that – besides the opening and closing of the garage door – meals are the best indicators of time. My days are measured in segments, a series of events leading to Max leaving and returning from school. I dream of summer, when there is no leaving, and we spend long days by the lake, fetching sticks, grilling burgers and diving off the dock into the water, our bodies weightless and free.

Mom peeks her head into Max’s room, peering in my direction. “Morning.”

My tail waves through the air, and I try to scramble over, slipping slightly on the hardwood, my nails tapping. I love how everyone in this family speaks to me – like I am human, too. Some dogs, their humans merely issue a set of commands: Sit! Stay! Go potty! There’s no conversation. There’s no humanity.

Have you ever tried to poo on command? Not that easy, not that easy.

“Good boy,” Mom says, crouching down and running her hands over the sides of my muzzle, which I’m told is almost completely white. “Yes, you’re such a good dog. How did you sleep, huh?” She kisses the top of my head, and I trail her into the kitchen, where something lingers. Stress. Anxiety. Sadness. I bet humans don’t know that emotions have specific scents, but for a few moments, they’re all I can smell.

A food bowl appears, and I swiftly eat my kibble – followed by a spoonful of peanut butter. When Mom’s back is turned, I sift the peanut butter over the roof of my mouth, clacking it loudly to extract the smooth, round vitamin, which I deposit covertly, deep into the crevice between the cabinets and the refrigerator. Emmaline waddles into the kitchen then, still in her footie pyjamas, and Mom hurries her towards a bowl of Cheerios. Generally speaking, Emmaline and I are on the same feeding schedule.

Everything is rushed this morning, I notice. Everything happens too quickly. Max blows into the kitchen, his hair wet, and barely says goodbye before catching the large yellow bus. Dad grabs a leftover container of spaghetti from the refrigerator and leaves without a word. And Mom ushers me into the backyard with a wave of her hands; I wander around for a few moments, do my business, and am almost immediately called back inside. This disappoints me greatly, as there were several interesting smells that I wished to explore: something rotting underneath a pile of leaves, smoke in the air, a yellow stain in the grass that might be my own but perhaps not.

I’m starting to feel anxious myself.

Later, Mom says, “Be a good boy today, OK, Cosmo?” and closes the front door, Emmaline in tow. Max has left the TV on for me in the study, for which I am always grateful. Days without TV are like days without oxygen; I am forced to wander aimlessly around the house, only the sounds of my claws clicking against the floor, the occasional ring of the phone. I sleep to pass the time, and awake groggy, determined to entertain myself with something, anything. Chew toys often lose their appeal after the first week. I have no cat to play with. The bathroom doors remain closed following that first instance, many years ago, when I discovered the joy of toilet paper, unrolling sheet after sheet in frenzied merriment. Television is my saving grace.

Max rotates between several channels to give me variety. The news is my least favourite. I do not see how humans stand it, or, frankly, how humans stand each other; sometimes it seems like the world is full of bad people doing bad things. (My family is an exception, of course.) The Discovery Channel is much more to my liking: tales of the Alaskan wilderness, survival in extreme environments, and fish bigger than me! But I must admit that my absolute favourite channel is Turner Classic Movies.

That is where I first discovered Grease.

It was a Friday night in late winter, and my family had ordered pizza from the restaurant next to the grocery store: three large pizzas with pepperoni, sausage, and extra cheese. The five of us settled into the study, where I strategically positioned myself as close to the pizzas as possible, earning several crusts for my efforts and unparalleled stealth.

“Oh, go back, that channel!” Mom suddenly said.

“This?” Max said.

“Yes! I haven’t seen Grease for so long. Trust me, you’ll like it.”

And I did. I liked it very, very much.

Grease is a cinematic masterpiece with wonderful songs, including “You’re the One That I Want” and “We Go Together”. No dogs grace the screen, but I do not hold that against it, because it has everything I love about people: passion, dance moves, and the resilience of the human heart. Nothing about humans is as complex as their hearts; I learned that from Sandy and Danny, the main characters in Grease, who fall apart before falling back together. I came away from my first viewing with an unmistakable sense of lightness. I tried not to act too excited, too changed, but before bed, I shoved my nose into my water dish and snorted several times, watching the liquid burble and fly – which was perhaps a clear indication that I was thoroughly and unexpectedly happy. That night, I fell asleep quickly. And I dreamed of dancing.

In some ways, I have never truly stopped.

4

Jealousy is not in my nature. Although, I’ve known dogs who are incredibly frustrated by their limitations – by comparing themselves to humans. It is not your fault, I try to tell them, that you have no thumbs to lift the TV remote, no skilful tongue to speak. And after all, dogs have many advantages over people.

Case in point: I have never seen a human on all fours, pressing his face to the ground, attempting to track a scent. Their noses are remarkably inferior to ours. I am no bloodhound, but I would recognise Max’s smell anywhere; I could follow the scent of his footprints through a forest scattered with leaves. If you need more evidence, please also consider the book To Kill a Mockingbird, which Max read last summer for school. No dog would have to consult a manual for such a simple task! To be clear, I have never killed a mockingbird, but for the sake of argument, it would be almost insultingly easy: track smell, put bird in mouth, close mouth.

Dogs are also superior in the following ways: we acknowledge danger when humans won’t – their capacity for denial is much, much greater. We forgive readily and often. And we do not feel one emotion while displaying another; take, for example, the prevalence of humans claiming “I’m fine”, when they are not fine at all.

I am only envious of people in two respects.

First, human families stick together forever, through ups and downs, highs and lows, because love binds them. I feel as much a part of the Walker family as Emmaline and Max … and yet I do wish I still knew my brothers and sisters. I wish I knew my mother; I remember so little of her.

And second, dancing.

For all their faults, humans can dance.

In the early years, Mom and Dad would switch on jazz music and dance barefoot in the kitchen. They’d intertwine their hands and sway side to side, turning now and then, while I looked on in astonishment. How could they spin so smoothly? How could they dip like that? As a dog, my initial reaction was to separate them; in the wild, few animals weave together without a fight. So I wiggled between legs, knocked into knees, trampled on toes.

Still, they danced.

Sometimes Mom and Dad would disappear for long stretches of night, stumbling home with tired feet. “You should’ve seen us,” they’d say, describing every detail: the songs, the atmosphere, the way they moved.

It wasn’t until Max and Emmaline arrived that something finally clicked, and I understood deeply for the first time how dancing is an extension of the soul. Although I am prone to exaggeration, I must say, without hyperbole or embellishment: dance nights transformed my family. Mom and Dad began staying in, rolling up the living-room rug, and the four of them jumped together and spun together and raised their hands together, music thumping through the house. Everywhere else, Max was shy, but in the living room he zigzagged, jiggled, skipped.

Him – this was him!

“Cosmo,” he always called to me, right in the middle of the dance, “come!”

In response, I’d edge backwards, slinking quietly on to the sofa. When I used to run (chasing a tennis ball in the dog park, breaking free from the yard to rush after Max’s school bus), I felt fluid and infinite, as if I were merely slipping through the sky. That is the closest I’ve come to achieving what I witnessed on dance nights, what I saw in Grease. I know my limitations. Especially now, with my joints and my bones, I will never stand for prolonged periods on my back legs, spinning in elegant circles and hopping effortlessly from place to place.

All I can do is dream. And dream, I do.

5

Early November passes quickly, and for a few glorious weeks, it’s as if the events of Halloween never occurred. The sad smell evaporates from the kitchen. Mom and Dad do not raise their voices. And Max is busy constructing a rocket for the science fair; it will shoot two hundred feet into the sky, right into the stars he loves so much. The weather is surprisingly warm, and Emmaline and I spend the afternoons jumping into pile after pile of autumn leaves, laughing ourselves silly. On the weekends, Dad cooks breakfast – banana pancakes, fried eggs, bacon – and Max sneaks me bits and pieces, which I gobble with enthusiasm. Occasionally, I save a half-strip of bacon, hiding it behind the couch for a rainy day, because you never know when rainy days will come.