8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

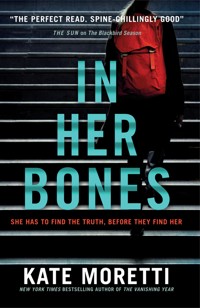

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

New York Times bestselling author Kate Moretti's (The Vanishing Year) latest novel follows the daughter of a convicted serial killer who finds herself at the centre of a murder investigation.Fifteen years ago, Lilith Wade was arrested for the brutal murder of six women. After a death row conviction and media frenzy, her thirty-year-old daughter Edie is a recovering alcoholic with a deadend city job, just trying to survive out of the spotlight.Edie also has a disturbing secret: a growing obsession with the families of Lilith's victims. She's desperate to discover how they've managed—or failed—to move on, and whether they've fared better than her. She's been careful to keep her distance, until the day one of them is found murdered and she quickly becomes the prime suspect. Edie remembers nothing of the night of the death, and must get to the truth before the police—or the real killer—find her.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 460

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also Available from Kate Moretti and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Kate Moretti is incredibly talented. In Her Bones is at once chilling and compelling, frightening and insightful—and truly madly deeply satisfying. You’ll gasp at every twist, and turn these hauntingly sinister pages as fast as you can.”

—Hank Phillippi Ryan, nationally bestselling author of Trust Me

“A suspenseful, whirling spiral of mysteries within mysteries, plot twists you won’t see coming, and characters linked by deadly fates that stretch across the years. Moretti’s prose is crisp and masterful, her people rich and real. Don’t miss this haunting, wild thrill ride.”

—David Bell, nationally bestselling author of Somebody’s Daughter

“We dove head-first into In Her Bones, its riveting twists and turns keeping us up well past our bedtime. Moretti has meticulously crafted this gripping mystery, which begs the question: Is it possible to escape our own fate? Another stellar contribution to the suspense genre.”

—Liz Fenton & Lisa Steinke, authors of The Good Widow

“Sensational; a stunning psychological thriller that kept me riveted from the first page to the last. A dark and compelling exploration of what it’s like to grow up with someone who just may be the worst mother in the world, Moretti’s chilling and insightful novel answers the question: If your mother is a serial killer and you’re obsessed with her victims, what does that make you?”

—Karen Dionne, internationally bestselling author of The Marsh King’s Daughter

“Suspense at its best: A chilling voice, an unlikely heroine, a haunting story. In Her Bones is Kate Moretti at the top of her game.”

Jessica Strawser, author of Not That I Could Tell

Also available from Kate Moretti and Titan Books

The Vanishing Year

The Blackbird Season

INHERBONES

KATE MORETTI

TITAN BOOKS

In Her BonesPrint edition ISBN: 9781789090109E-book edition ISBN: 9781789090116

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: October 201810 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

© 2018 Kate Moretti. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book?We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:[email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

TITAN BOOKS.COM

For Dad, who’s read every book and liked most of them.And because I can’t dedicate this one to Mom.

Excerpt from The Serrated Edge: The Story of Lilith Wade,Serial Killer, by E. Green, RedBarn Press,copyright June 2016

Timeline of Murders (For reference)

February 1998: Renee Hoffman, stabbed nineteen times in her abdomen, chest, and face (the only victim with face lacerations); found in her car twenty-two hours after being reported missing. Spouse: Charles Hoffman, home, alibi confirmed (via phone call with mistress).

May 1998: Melinda Holmes, found stabbed eight times in her backyard. Fiancé: Matthew Melnick, at his residence. Father: Walden Holmes, asleep upstairs when murder occurred (alibi confirmed).

March 1999: Penelope Cook, stabbed fourteen times in her living room. Spouse: Mitchell Cook, away on golf outing (deceased since 2010; alibi confirmed).

October 1999: Colleen Lipsky, found behind her apartment Dumpster; stabbed three times. Spouse: Peter Lipsky, away on business (alibi confirmed).

November 2000: Annora Quinlan is stabbed seventeen times and her ring finger is removed, including her wedding ring, neither of which were ever found. This is the only victim to be missing this finger. Spouse: Quentin Kitterton, away on business (alibi confirmed).

June 2001: Margaret Mayweather, stabbed twelve times in the abdomen and torso while in her bed. Spouse: Troy Mayweather, away on business (alibi confirmed).

June 2001: Lilith Wade arrested for four counts of criminal homicide, murder in the first degree. She was thirty-four. She was eventually convicted of six counts of murder in the first degree in the city of Philadelphia and surrounding areas.

PROLOGUE

Eileen Dresden is blond, harried. Her wispy bangs brush along her brow line and she throws her head to get them out of her eyes. Her twin sons are seniors in high school, their arms ropey and thick, their laughs loud, their eyes dancing as they tease their mother. Eileen smooths back her daughter Rayann’s hair with a flat palm and a kiss to the crown of her head. Rayann, awkward and quiet, watches her brothers roughhousing until one of them slaps down on the chicken ladle and sends it flying, chicken bits and gravy splattering on the white carpet (who has white carpet in a dining room?), and Eileen starts to cry. Kent barely looks up from his phone, oblivious to his wife’s tears.

Kent is a motherfucker.

Kent is having an affair. He barely tries to cover it up. She comes over three times a week after Eileen leaves for her job as a teller at the bank. Kent is a software development engineer and works mostly from home.

Sometimes, he smiles at his wife, a quick blip of a smile, and her face relaxes and all the lines disappear and you can almost see how they used to love each other. Back when he was a programmer and she was working in marketing, making brochures for a software company, when software companies were all start-ups, when they held late-night meetings over Chinese food and dry-erase boards and had sex for the first time on the conference room table.

Everything is different now. See, in 2000, when the twins were barely toddlers, and Rayann was a bouncing newborn, Eileen was in the prime of her life. She was so happy then. She wasn’t working, she was a mom. But the good kind, the kind who went to baby yoga classes and sang along to Barney. The kind who arranged toddler playdates with the moms in the neighborhood so the kids would all be best friends before they got to kindergarten. She hosted tea parties and sank into motherhood the way other mothers sink into vodka. She hugged her children, freely and often, and smelled like Love’s Baby Soft, which she has used since college.

But then in November of that year, everything changed. Eileen’s sister, Annora, married a man named Quentin Kitterton. Not even a month later, Annora was found murdered in their townhouse in Philadelphia. They suspected Quentin for a long time. It didn’t help that Quentin was black and Annora was white, so for months, maybe a year, they looked too long and too hard at Quentin before eventually moving on to his past. To all his women, and his philandering, and eventually, a smart, savvy young junior detective found a connection no one else did.

Lilith Wade.

Lilith worked at a bar called Drifter’s. The kind with only a few blinking signs and even fewer patrons. Lilith was pretty, you know? A little overly made up, a little hardened around the edges, but she knew what to do and how to do it and didn’t bring home any of the hassle, either that time or all the other times Quentin went back for her. She was a nice, easy, sure thing in a world with so many unknowns. That must have made a man feel good. Then he met Annora and moved on, as men tend to do.

Until Lilith snuck in through the bathroom window and stabbed Annora seventeen times while Quentin was away on business. Posthumously, Lilith removed her ring finger, including her wedding ring, neither of which were ever found.

With Annora gone, Eileen was never the same. All the life just eked out of her like she died the same day as her sister. Her children never knew the mother she could have been, how present, how attentive she used to be. They got used to the new Eileen. Harried. Distracted. Sad. Until it all just seemed like normal, regular life.

The most infuriating part for Eileen is that Lilith doesn’t remember. There were six women in total, and she only remembers a few of them. Some of them she’s even denied. How could anyone forget her sister, who was so full of life before Lilith stole it from her? It seems to Eileen to be the cruelest irony. Or at least that’s what she rants about in the online forum, a gathering place for a handful of Lilith’s victims’ families and victims of other violent crimes. Healing Hope. Such a mawkish name for the graphic atrocities that are discussed there.

Eileen doesn’t know that she and I are connected. We’re both Remainders. We’re what’s left after Lilith, part of a small, exclusive, horrific club. Some of them know one another. None of them know me. It doesn’t seem possible that one person can cut such a large swath of destruction through a city. If they knew who I was, they’d turn their rage—their helplessness, the never-ending hell of grief, the feeling that death row is not enough punishment—toward me. After all, we share the same blood: microscopic pieces of Lilith coursing through my veins, our molecules alike from the dark parts of the heart that no one can see, right down to our bones.

Lilith is my mother.

1

Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Your life is more open than you think. You think you’re safe. You have neighborhood watches and room-darkening drapes, password-protected computers, alarm systems, and garage codes that are absolutely not your firstborn’s birthday. Even with all that, it’s practically there for the taking. Anyone can find out anything about you, and sometimes, if they ask the right way, you’ll just tell them.

People are too trusting. Naive. Even with the news blinking tragedy and fear in a nonstop cycle, we still trust. Well, you do.

I don’t.

I’m a good person, although on paper, it might be difficult to convince anyone. I don’t seem like a good person. I’ll tell you that I only ever use what I uncover to help. Have I taken things too far? Sometimes. Am I sorry? Almost never. In the darkest parts of the night, when the truth is laid bare, I’d like to tell you that I have regrets. I have some, everyone does. But not about the watching. Alone with my thoughts, the only question I turn over and over is Am I like her?

I pull the hair off my neck, it’s hot already and only 7:00 a.m., but that’s Philadelphia in August. The air itself sweats.

I head north on York Street, where I’ll pick up the El. I do feel a weird bubbling in my chest on Monday mornings. Not so much because I love my job, but because I love the stability of it. I enjoy being able to go somewhere, at a particular time each day, and be useful, industrious. I like sitting in my cube, tapping at my computer, hitting send or filing the latest report. I like answering emails, checking things off my list. I like being told I’m efficient. I am efficient, in every aspect of my life.

I am lucky to have a city job, a clerk, technically an “interviewer.” It’s a government job that I don’t deserve, with good pay and decent benefits. I sit on the phone with criminals for hours at a stretch, obtaining bits and pieces of boring data that the police can’t waste their time collecting: addresses, aliases, Social Security numbers, basic information for the public defenders. The other half of my day involves writing reports and processing court fees and parking fines.

Sometimes I see Brandt on my commute. Gil Brandt, the detective who arrested Lilith. The man who gave me a second, third, and fourth chance. It’s complicated, but probably not in the way you think. Or maybe exactly in the way you’d think.

Today, there’s no Brandt. Just the orange stacked seats of SEPTA, the blank, dreary faces on a Monday morning, the vaguely warm odor, like the inside of a public dryer: a little wet, a little musty. The man next to me huddles into the window, a paperback folded into his hands, his cracked lips moving to the words, even as his eyes dart up and out the window, down the metal floor, gummed with black. The seats are full, and the aisles are crowded but not packed, the faint fug of an armpit over my shoulder. I’ve taken the El every day for five years, early mornings, late nights, the train punctuating the days and giving me a structure and definition that keeps me forward-looking, which hasn’t always been my strong suit.

Two rows above, a blonde turns, her hair falling into her eyes, her fingers scraping the metal pole by her seat, and her eyes resting on me, only for a second, but long enough to feel their zing. Lindy Cook. Couldn’t have been more than twenty, her mother taken by Lilith’s rage when she was a child, maybe even a toddler. Lindy, so small when she lost her mother, a toddling, swollen towhead with a red sucker and pink-ringed mouth in all the court pictures, was now a lithe, lanky dancer, an apprentice at the Pennsylvania Ballet. That was all I knew. I search my brain, my memory for something—any detail about her life—and come up blank.

And now she was here. Here! My train. Why? She’d never been on this train before, and I took the El every day. The brakes squeal at 13th Street, the forward momentum pushing me into the pole in front of me, sending the arm over my shoulder bumping against my head. I stand and Lindy stands, and across the train we make eye contact again, her face blank as a stone. My heart thunders, my ears so filled with it that I barely hear the loudspeaker garbling nonsense. We head for the same door and I hang back, watching her step onto the platform. She tosses her hair, and I catch the smell of damp jasmine. She keeps her head low, only to look back just once (was it nervously?) at me.

Up at street level, she heads north on 13th Street, my direction, and I wonder once, crazily, if she’s coming to work with me. If she’s looking for me, if she’s found out about me, who I am and what I do, some kind of sideways revenge scheme for taking her mother, which is, of course, no more sideways than what I do to them. I follow her for two blocks, blocks I would be walking anyway, but I stay a good five people behind her, the bobbing heads of bankers and jurors, lawyers and judges, bopping headphoned dudes appearing in court to fight parking tickets, clerks at Macy’s, and cubicle swampers from the Comcast building. Lindy’s head isn’t hard to follow, the blond shining like the sun against the gray.

She passes my building and I nearly jump out of my skin, thinking she’s going to turn left onto Filbert and I’ll be forced to follow behind her, wanded through by security. But she passes right by, picking up speed, her long legs moving her faster than I can keep up. She stops at an intersection, picks up a paper and a hot Styrofoam cup at a street vendor, offering him a smiling hello and a laugh. The kind of exchange that evolved organically, after an established routine. She darts across Broad Street, six lanes of traffic, and disappears inside the Pennsylvania Ballet studio building. Before pushing through the revolving door, she glances back at me once with a questioning look, her head cocked to the side. I stand on the street, frozen, watching her recognize me as the girl from the train, and now, oddly, the girl who followed her here to the place where she thought was she safe.

* * *

My desk is in the basement: a gunmetal gray and fabric nothingness that lends itself to both slog and productivity in equal measure. Unlike my coworkers, even Belinda who is relentlessly chipper, I don’t mind the drear. The sides are tall enough to maintain privacy, and I tuck myself into the corner, compiling reports, processing parking and court fines with enough focused efficiency to please a myriad of bosses.

I hurl my bag onto my desk, knocking against Belinda’s cube, and her black, bobbing head appears. Her face is flat in a pretty way, her mouth and nose pressed together like she’s perpetually grinning. Her cheeks flushed with health. Belinda is simultaneously hard to like and dislike.

“Hi! You’re late. You’re never late.” She says this without judgment or curiosity, just that it is a fact. She’s right. I’ve never been late.

“I know. The train,” I offer feebly with no real explanation, Lindy’s face still fresh in my mind, her blue eyes widening with recognition, her glossed mouth parting, the faint scrutinizing dip in her eyebrows. I don’t have the patience for Belinda’s weekend recap: underground clubs with her singer boyfriend, the winding drama of her two closest friends.

“Weller is looking for you. There’s a guy on line one, been in the tank since last night.” She sucks a mint around her teeth, her tongue poking into her cheek to find it, and at the same time, takes a slug of coffee from a Starbucks paper cup. She means the interview lines, and she waves the contact forms in front of my face. Name, address, aliases, birthday, age, arrest code. Collecting information is something I’m particularly talented at. Criminals take a liking to me; I’m easy to talk to. The psychology of someone caught has always been interesting to me. Sometimes they open up, saying more than they should. Sometimes, they’re new to the system, and they clam up, terrified, forgetting their addresses, their minds wiped. Sometimes they’re high, or worse, coming down. Other times they’re straight as a beam. The women are usually less trusting, but only at first. It’s generally my favorite part of my job, talking to them.

“Can you do it? I think I’m coming down with something. My throat.” But I motion to my head, some undefined sickness overcoming me, and she shrugs and wanders off, presumably to find Weller, my boss du jour. Management cycles through like the seasons around here; only the lower levels, the drones like us, persevere.

My computer chugs to life and before I open my emails, I navigate to Facebook and search for Lindy Cook, her wide smile filling my screen. Her profile is locked down; the only pictures available to me are those used for her profile. Her email and even her username are hidden. Damnit. Quickly, I navigate to her friends list and give a silent cheer when I find it’s public. I download the profile picture of one of her lesser friends—toward the bottom of her list—and in a new tab, make a new Facebook profile. I use the same name, the same picture, and click on about twenty-five of their mutual friends and select Send Friend Request. Immediately, three of them accept. I wait five minutes, and Send Friend Request to Lindy. I push back my chair, walk purposefully to the kitchenette and make a cup of tea, dunking the bag, feeling the curl of steam against my face.

The Facebook trick was one I’d perfected on Rachel. She was so trusting. Truly darling.

I’d been sober, working at the courthouse for a year before it occurred to me to use the system to look up people I knew, before things fell apart. Keep an eye on them. Rachel was washed out and plain. Married to a man with a round belly and freckled nose, an infant tucked between them on the beach, his pale skin ruddy from the sun. It hadn’t been difficult; she wasn’t hiding. She worked as a teacher for a charter school, just like Redwood Academy. Her Instagram was heavily populated with filtered images: flowers, the sky, her baby girl; her posts captioned with long, poignant statements about love and life and motherhood and teaching. If I met her now, I’d forget her immediately: she was simple and emotionally displayed. I looked at every picture, dating back two years, and chewed on TUMS the whole time. I wonder if she ever thought about the girl from high school, the one with the murdering mother? You’d never think she knew such a person, not by looking at her.

But then, you can’t tell anything about anyone by looking at them.

Mia had a Twitter account but no Facebook or Instagram. She was a journalist with bylines in the Inquirer until a few years ago. Now she’s an editor, practically invisible. She periodically tweeted out her articles, and other sociopolitical commentary. Zip on her personal life. I searched public records. No marriage. No kids. An order of protection against a man named Samuel Park, stemming from a controversial abortion story she’d written, dating back to 2012. It took some digging but I found her apartment, a condo unit in Radnor on the Main Line. Not horrifically expensive, but not cheap, either. One picture in her media files: a girl’s night (#GNO!), sleek hair and little black dresses, high heels and red lipstick. Three women, all virtually interchangeable. I couldn’t have told you which one was Mia.

Neither of them had a life I wanted.

Still. The hunt thrilled me. The flush of heat against my neck at each discovery, the way the keys flew under my fingertips, the information seemed summoned at will— almost effortless. The ease with which people gave up what felt to them like innocuous information: their first pet, their first car, their favorite teacher. Nothing about the internet felt real—to me or anyone else. I wasn’t breaking any laws, doing anything immoral or unethical, none of it was tangible. It was all bits of data flying around in space; who cared about individual little bits of data? I enjoyed the manipulation, this gentle bend of virtual facts.

Mia and Rachel were boring. Then I realized that while Brandt knew me so well, I knew very little about him. I started with his ex-wife, now happily living in an Atlanta suburb with her new husband. I friended her on Facebook, my profile picture a stargazer lily, beseechingly raw, almost vaginal. A pic from the garden! I’d called myself Lily Beck, so stupid, so traceable to me—I was my own first lesson. People choose nothing at random. Not passwords, not usernames, not pet names, nothing. A few months later came a text: Unfriend my ex-wife, Beckett. That was it. No explanation, no further instructions. I didn’t ask how he figured it out. I didn’t protest, although I’d wanted to. I hadn’t done anything wrong. I just watched her life (Her name was Mabel. Mabel! Like a storybook heroine). Honestly, what else is social media good for? The pictures of her new husband, her gabled McMansion in a plush neighborhood, dinners at the country club, her mouth wide and laughing into the camera, her skin glowing and dewy from the southern humidity. Her skin looked dipped in gold, glittering and creamy.

Why? I know this is in me, this impulse to obsess, to stand on the outside with my hands pressed against the glass. Bored with Rachel and Mia, caught by Brandt, I had punched Mitchell Cook into the system at work on a whim. I guess that’s how it started, but who’s to say? Do you ever question how anyone starts a hobby? When exactly and why did you take up knitting?

I’d imagine that everyone on the precipice of thirty examines their life and finds it wanting in some way. But as an on-again, off-again alcoholic with no life, no boyfriend, and a job in the courthouse basement—which let’s be honest, is as dank and dark as it comes—the gap between myself and everyone else my own age seemed interminable. Late one night, I saw an interview with Matthew Melnick, the fiancé of Melinda Holmes, during one of the docudramas. He had said some of them had found each other, found comfort together, in an online forum called Healing Hope. At first, I just watched them talk to one another.

Maybe I wanted to know: How did they move on?

I started to loosely keep track of them all. What had become of the people touched by Lilith? Touched by Lilith. Listen to me sanitize. What had become of the people whose loved ones were murdered by my mother?

I have more in common with the collateral damage of Lilith’s crimes than with anyone else. The only people I feel any affinity toward are people I’ve never met. Lilith Wade shelled me, scooped out my insides with her thin matchstick fingers, and derailed any meaningful life I might have had—and she’d done the same thing to them, too. I’d wondered how they moved on, grew up, became adults, had children. Did the rest of them move away, start over, remarry? Some did. Most stayed in the area, many within city limits: the Dresdens, the Hoffmans, the Mayweathers. Lindy Cook. Walden Holmes.

Peter Lipsky. Yes, I have favorites. Why? I don’t know. He’s the hardest, so there’s that. I’ve always liked a challenge. I can hardly ever find anything interesting on him at all. It has to be there, though, it always is.

How quickly it became second nature, not something I did here and there, but rather something I now do. Repeatedly, if not daily. I find all their speeding tickets, their jury duty summonses, and once a public urination fine—Walden was a bit of a drunk—and simply erase them. Delete. Mark as PAID IN FULL. It’s an easy reach and makes the rest of it seem fine. Justified, even. A few months ago, Walden got into a bar fight. I’d wanted to dismiss the arrest record, but I don’t have access to that system. Yet.

Now it felt as routine as making coffee in the break room.

Back at my desk, Lindy accepts. I open her profile and scan through, looking for an email. Most people set their privacy to the default friends only and never think about it again.

LBaker62998. Lbaker. Lindy Cook. Cutesy.

In the Google search bar, I type in LBaker62998. A long list of results pops up, all the places she’s been, the places she’s logged on. Comments on Wordpress blogs, a Flickr page, a forum for dancers, and a long list of posts whining about the corps, being looked down upon as an apprentice, a question about back flexibility and bunion pain, and inexplicably, a forum for pregnancy, which I slot in the interesting-although-not-immediately-relevant column. Then I see it, a post, made six months ago on Healing Hope. I click on it, my hands shaking. My mother was killed in a famous crime. I can’t tell anyone. I think about it all the time now and I don’t know why. I can’t stop reading old newspaper articles. I was only a baby. Should I get counseling? 722 responses.

“Beckett.” Weller is hovering over my shoulder, a scrim of stubble along his jaw, his voice wet and garbled, a thin sweep of gray across his red, gleaming crown. He cranes to look around me, to my screen, and I angle in front of it and give him a smile. “Can you get the guy on line one? 5505, nothing major. He’s drying out.” 5505 is a drunk in public; these are most of my interviewees. These guys also like to fight, so sometimes I get the aggravated assaults, too. Which is fine, they all sound the same on the phone.

“Weller, I’m feeling kind of sick.” I clear my throat, force my voice froggy. His eyebrows shoot up, I’ve never begged off a job in my life. “I think Belinda said she’d take it?” I hate the upward lilt in my voice, the question. It’s unlike me and Weller knows it. He rubs his palm against his cheek and grumbles.

“Check your email. We’ve got a department meeting at one, okay?” He ambles away, stopping at a desk down the hall to pluck a Hershey’s bite size out of an open candy jar. His pants hike up as he walks, exposing a thin, vulnerable strip of pink above his black socks and work shoes.

I swivel around, look back at my computer, and start skimming the responses. The first hundred are standard and repetitive.

Yes, you need to see a professional.

Please get help. Don’t read the articles, you’re fixating on it.

Have you tried hypnosis? Helped me tremendously!

Then, I see it. Lindy, can you get in touch with me? [email protected].

I knew I had seen Lindy’s username before. She and Peter Lipsky talked sometimes, but I hadn’t connected LBaker62998 to Lindy Cook. Why would I? Maybe I’m slipping. I feel the odd, unwelcome pang of jealousy, a thing I can barely justify, as I imagine Lindy and Peter, exchanging late-night texts, emails. I wonder if they’d talked on the phone, met in person? I imagine her long, gold-spun hair twisting around her finger as she listened to his doe-eyed talk about the grief that wakes him up at two in the morning, keeping him awake until his alarm goes off.

I imagine how taken he’d be with her, over a cup of coffee at Mickey’s Diner, if he’d fumble with the sugar, trying to tear four packets at once, and if she’d cover his hand with hers, deftly opening them into his coffee for him. Peter is awkward, Lindy is young, charismatic. I click through to Peter’s Facebook, only a handful of pictures. A narrow face, square jaw, blue eyes, hooded and sleepy. A thick roll of hair, scooped pockets of purple under his eyes. His cheeks flushed red against the fall backdrop of an outdoor biking trip. His smile thin, more like the memory of a smile, deep parentheses around his mouth.

* * *

Peter Lipsky is an insurance claims adjuster. He lives alone in a one-bedroom apartment on the first floor of a stone house in Chestnut Hill. His Facebook page is more public than it should be, but all I’ve been able to glean from it is that he’s a Flyers fan. He posts a few updates during the games but now, in August, he’s fairly quiet. Once a week, he checks his astrology and it automatically posts. I bet he has no idea. His smile is nice, if not vulnerable and almost wounded. In other words, he’s nearly invisible. In a crowd, I’d never pay any attention to him.

He has an older photo: a church, a white, billowing dress and big blond hair, and himself, tall and thin, the tuxedo hanging limply from pointed shoulders. This picture I save to my desktop. I blow it up, try to look at her face, but it’s too grainy. It’s a photo of a photo, the original taken sometime in the nineties, before smartphones and social media. Before the internet really took off, so there’s nothing about her online that doesn’t come from Peter, which is fine, really, because I already know her name. Colleen.

Before she died, Colleen was a pediatric nurse. Lilith never talked about Peter. She’s talked about the others: in interviews with police or psychologists or once a reporter. But if they bring up Peter she blinks wetly, confused and open mouthed. As far as I know there was no connection between them. No affair, no passionate love like Quentin. Colleen and Peter were married for nearly three years before Lilith came. Peter was at an insurance conference—who knew there was such a thing—and Colleen had taken the trash out to the Dumpster. They lived in a condo complex not far from where Peter lives now, and the Dumpster was on the dark side of the building. Lilith stabbed her three times in the chest and left her in the dark. Two of the three wounds were surface. Hesitation marks, they call them.

Another tenant found her eight hours later. They connected all Lilith’s victims through psychological profiles, victim commonalities, and stab wounds. She used the same knife: a combination serrated and plain edge utility knife, a common tool for hunters because it cuts both wood and bone. Later she’d claim she’d gotten it from her daddy, a man I’d never known or even heard her speak of.

Colleen was somewhat of an outlier. Police, investigators, lawyers, even Lilith herself could not tell you why she was killed. This, as I learned through forum posts, drives Peter absolutely crazy. Why Colleen? How do they know for sure, if Lilith Wade won’t confess? He has nightmares about it, waking up at all hours, unable to fall back to sleep until he logs into Healing Hope. He talks to whoever is there. Sometimes that is Lindy, sometimes it is a handle called WinPA99. I had no idea who that was, a search of her name turned up nothing. I only knew she was female because Peter once asked another forum member where she was. I couldn’t connect her to Lilith.

In Healing Hope, I spend my evenings watching the forum members’ usernames blink in and out. I never post, only observe. WinPA99 has never posted, either, and she only speaks to Peter. She is grieving her sister, murdered almost twenty years before. Some of their posts and responses are public. Lindy comments all the time and talks to anyone who listens. Peter is only ever active in the middle of the night, like me.

He hasn’t been online in a week. The longest I’ve ever seen him go.

The squeak of shoes brings me back to the present. Weller. I click out of the internet window and back to CrimeTrack, the city’s system for logging dispatch calls and incidents. I fake a cough, hacking into the crook of my arm. He pauses behind my desk, shielded by the half wall, and thinks I can’t hear him breathe: the hefty rasp of a man who likes his McDonald’s and cheesesteaks. Then, he’s gone.

I type Peter’s name into the search bar, and I’m surprised to see a return. Logged two weeks ago: a suspected break-in.

Lipsky, Peter. 7/19/2016: Call received at 11:27 p.m. Suspected break-in. Nothing reported missing. Caller distraught. Claims apartment is disheveled. Officer on scene says apartment appears in order. See log #769982.

I’m irritated at myself for missing this. I’d been distracted by the others.

Maybe I’ll leave early today.

2

Gil Brandt, Philadelphia Police Department, Homicide Division, August 2016

When they got the radio call about the DOA in Chestnut Hill, Gil Brandt didn’t think much of it. Another day, part of his job. Chestnut Hill was a bit unusual, not too many grisly scenes in those parts, but not so out of the norm that he’d given it much more than a passing thought. Called in by a down-the-hall neighbor; they meet every other morning at seven for a two-mile run. He’s never missed a day, the neighbor stresses. He looked in the window and could just make him out on the bed. He watched him for two whole minutes, banging the side of his fist against the window, and he still never moved. Figured he had a heart attack and called 911. The squad had called homicide as soon as they arrived on scene.

He took his time, stopped for coffee. He wasn’t the lead on the thing, he just had to show up. In Philly, they worked in teams; it wasn’t like the movies. He didn’t have a partner. The whole squad pitched in, whoever was available, and worked the case, top to bottom. Sometimes they solved it, sometimes not. Mostly, they solved it.

The guy in the apartment in Chestnut Hill had been shot. Two bullets to the chest—close range—while he slept. It didn’t even look like he had time to sit up and fight back. He lived alone, a seemingly sterile apartment, but what did Gil know? Since his divorce eight years ago, on any given day, he had a three-day-old pizza box sitting on the counter. Brandt wasn’t a slob, but he wasn’t what you’d call tidy. This guy? Listen, there are two kinds of people: clean people and people who clean for company. You can tell if someone is a clean person by the hair in the shower drain and the inside of the microwave. This guy didn’t just clean up for a guest, he lived this way. Brandt thought everyone should have better things to do.

They find the long, wavy hair in the drain. Turns out, the guy had a friend. They find the used condom in the basket next to the bed, wrapped thoroughly with toilet paper. They find the matching blond hair on the pillow next to him. He had a girl.

By luck or chance, Brandt gets assigned the task of finding the girl. The DOA’s phone is PIN protected but the department’s tech guys can crack it open in usually under an hour. A four-digit PIN yields ten thousand combinations, and it takes the code crack software only seven minutes to nail it down. After that, it’s easy street. Sometimes Brandt thought technology was making cops dumber. His new guys could tell you in a second how to run a code and catalog someone’s entire hard drive but sometimes they couldn’t tell you the first thing about what to do with a DOA who didn’t have a smartphone. You used to have to pound the pavement for clues, the gumshoe way. Now, between the contacts, photos, historical data, and GPS metadata, everything you need to know about anyone is sitting in their pocket.

The DOA was no different. Except no girlfriend that he could find. No pictures of them together on his phone, just a sad little collection of birds and panoramic views of Hawk Mountain in what looked to be fall. So, almost a year ago. His contact list was anemic—a handful of men’s names. His texts were infrequent but the most recent was from a guy called Tom Pickering, mostly about work. Pay stubs in the kitchen told Brandt he worked at True Insurance.

The True office was subdued; just the appearance of a cop on the day their boss skipped work, the same guy who’d never even called out, not once in eleven years, sent hackles rising. Brandt asked for Tom Pickering.

“Jesus,” was all Tom could say when Brandt told him. He hated telling people about their loved ones. But this guy didn’t seem to have loved ones, just Tom, who kept running his hand through his hair, over and over. “Jesus, Jesus.”

“When did you see him last?”

“Jesus,” he said again, and Brandt had to wonder if he was a particularly religious man. “Last night. Everyone else went out for a retirement party. He took a girl home. I, uh, worked late and then my wife got mad, so I went home.” And the weight of what he said and its implications hit him. His face paled and Brandt had to grab him a chair. He looked like he might pass out. “But it’s all anyone’s talked about. He took a girl home. Evie something. They said she was pretty! Shit, he never does that. Holy fuck, did she kill him?” Not religious, then.

“We don’t know, Mr. Pickering. Thanks for your time, though. Who went to this party and where did they go?”

“Lockers. I guess they left together.” Pickering shook his head. “Jesus.”

“Who else can I talk to, Mr. Pickering?”

Tom Pickering gave Gil a list of names, rattling them off and motioning vaguely to the cubicles on the other side of the office door. Gil talked to all of them, the same story. Eve or something. Left early. Pretty. They seemed to know each other. Together by the time we got there.

The thing people don’t get about murder is that it’s a mostly stupid act committed by mostly stupid people in their most desperate moment. The other thing is that whoever you think did it in the first day of the investigation, nine times out of ten, actually did it.

Brandt just had to find the girl.

At Lockers, the bartender was leaning against the bar, watching a flat-screen in an empty room. It was barely noon.

“Yeah, I remember that guy,” he said when Brandt showed him a picture. “Went home with a girl.”

“Get a name?”

“Sure, she paid for drinks with a credit card.” The bartender went to the computer and started clicking around.

See? Mostly stupid people.

The bartender printed out a transaction record and Brandt couldn’t help but think that he was losing the excitement somewhere. Sure, technology let them be more effective, quicker. Ultimately, it was a good thing. The arrest rates were higher. The chief was happy. The mayor was happy. Still, some days it seemed to come too easy.

He took the paper and studied it. They had enough vodka tonics for two. Plus a few beers. He scanned to the bottom for the name and felt the blood drain from his face. He took out his phone and pulled up her picture, blew it up for the bartender to see. Just to be sure.

“Yeah, that was her,” the bartender said, running a towel down the length of the wood.

He hadn’t been surprised by the job in a long, long time.

3

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Tonight, I skip dinner, too tired to heat anything up, and instead lie in my bed on top of the blankets, picking a padlock. It’s an odd little hobby, but a soothing one. I found a box of padlocks at a yard sale years ago, and have been working my way through them with a tension wrench and lock pick set. Something about the click and slide of those tumblers, like solving an illicit puzzle. It takes a fine touch, sometimes feather light, but it’s predictable, too. I like knowing, a fraction of a second before it happens, that success is imminent, feeling the steel loop pop in my palm.

I listen to the television next door through the thin walls, a sweet plume of weed seeping under the door. The Georgian row home is old, the floorboards narrow and creaky, so I can hear every footstep. I can hear Tim, my neighbor, his voice low and deep, talking on his phone, and I imagine his hand pressed there, between our shared wall. I hold my breath, hoping he wouldn’t suspect I lay merely feet away, and with the light off, would maybe assume I hadn’t come home yet, had he ventured outside to look to the left at my bedroom window. I always come and go quietly, or loudly, depending on whether or not I’m in the mood for Tim. Tim’s a good guy, in a teddy bear kind of way, with his well-groomed beard and big laugh and rumbling train of a voice. He’s great-looking, that’s part of the problem. Exceptionally good-looking men are all assholes. He’s used to women who giggle at his jokes, corny dad jokes, jokes about how many people are dead in that cemetery (all of them! ). I know deep down he just wants a wife: someone nice and sweet to settle down with, buy a big Colonial in Elkin’s Park with a wraparound porch, the kind with spinning ceiling fans on hazy August evenings.

He raps on our shared wall. “Beckett, you there?” I breathe shallowly, waiting until I hear him walk away, back through his apartment, away from our wall, and he’s gone. It only takes a minute or two for the doorbell to ring.

Jesus Christ.

I get up, walk thirty steps, crack open the front door, and tell him he’s a pain in my ass.

He laughs. “Let me in.” He smiles, which is nice. He has straight white teeth and dimples that you can only vaguely outline through the scruff on his cheeks. He waggles a half-consumed bottle of wine at me.

“No.” I’m 119 days sober. He has no idea.

“Come on, Beckett.” He smiles again, all teeth, and I almost cave. It would be easy. He cranes his neck, looks past me into the hall, straight into my bedroom, where I’d left the door wide open, and I move to block his view. “Why are all the lights off?”

“Because I didn’t want you to know I was home.” I start to shut the door in his face and he slaps it open, his foot wedged between the door and the jamb. I roll my eyes and he again holds out the wine, a peace offering. I take it and give him a look. He backs up, holds his hands up, and laughs to himself as he walks away. I watch him retreat, the plank of his back, his long legs, and regret it, for a second, but only a second.

“Why do you put up with me?” I call to his back. He half-turns, I can’t read his expression in the flickering hall light but his voice is teasing.

“You make me laugh,” is what I think he says, but when I ask him to repeat it, I hear the click of his door.

In the kitchen, I pour the wine down the sink, holding my breath. I don’t want to smell it, the tangy tannins making my mouth water. I might end up licking the stainless steel, just to feel the tart pop on my tongue.

I always get that same twinge around Tim, as though I’m pulling him along by a leash and he knows it. I can be this woman he wants, but only periodically, and we both know she’s not real. He knows nothing about Lilith, or the booze, or my probation. He knows my brother exists but only because Dylan calls seven times a day. I’d think that normal women tell the man they’re sleeping with these things. Maybe not?

The day he moved in, a year and change after me, he had a girl helping him. A tall, lanky blonde, the kind with low-slung jeans and high boots and a happy, burbling laugh that flitted through the walls, invading my living room. I thought she was moving in, not him. I had to leave, it got so bad, and all I kept thinking was, Oh hell no. If The Laugh was moving in, I was moving out. I escaped to the library and started browsing for a new place. When I came back later, as I tried to pad quietly past his apartment, the door flung open and there he was, a wall of a person. That smile, easy. And honest to god, my heart actually raced. Dark hair, dark eyes, but nice, you know? The kind of nice that would chase after a frazzled mom who dropped a five-dollar bill. You could just see him helping an elderly man on a bus. You could see it all in an instant and that apparent kindness made me nervous.

The girl was gone. I’m Tim, he’d said, holding out his hand. The girl, I found out later, was a friend. Not a girlfriend. He’d told me this hopefully, a glint in his eye, with a smirk. Weeks later, I called her The Laugh and he’d hooted. I felt my cheeks grow warm, and that’s when I knew I’d have to be careful.

The last guy I worked hard to make laugh was Brandt. I never have been cut out for this kind of thing: dating, relationships. Don’t get me wrong, I like men. And I love sex. And neighbors, well, they’re convenient. But the whole share-your-lives part? The pillow talk after? People whisper about their deepest-held beliefs, childhoods, parents, memories. All the building blocks that make a person. I couldn’t navigate any of that.

Not to say Tim doesn’t push me, he does. Last week, Wednesday, he tried to take me out to dinner, a real dinner, not this takeout Chinese thing we do on his living room floor, and I hid, the way I tried to do tonight, with the lights off, and listened to him knock on my door, call through the wall, Beckett, I’m wearing a tie, for God’s sake, I know you’re in there. I knew I was being an asshole. The day before, I fell asleep in his bed, something I rarely ever did. When I woke up, he was watching me, the edges of his face blurred like Vaseline over a camera lens, a tilt to his head, a hank of my hair twining between his fingertips, and I could just tell. People can tell when they’re being loved. There was something duplicitous about it. How can you love someone you don’t truly know? The answer, of course, is that he only thinks he does.

Then I think about how he’s never been in my apartment, not once, and doesn’t question me about it. I ask you, how is this normal? What must he think? Instead, he always laughs, chucks me on the chin, punches my arm, tugs my hair, a third-grade playground crush. He doesn’t know what to do with a girl who is made of needles.

It all suits me just fine, because when I’m really gone, I can’t feel guilty about him, too.

* * *

The last time I had a friend was high school. I was part of a crowd, maybe even the right crowd. Mia, pretty but mean, Rachel and I little shadows in her sun. Mia led, Rachel and I were happy little followers. Until I wasn’t.

I remember the way Pop said it: Your mom, Edie. I thought she was dead and felt almost relief. A slipping into nothingness, the way you slide into a cold creek on a hot day. I swear I almost felt happy. Until he said, She’s been arrested. I couldn’t help it, I rolled my eyes. For what? It had happened before and I was certain it would happen again.

This is different, and I realized for the first time that my father was old. His skin was graying, his hair thinning, his lips cracked around the edges. In that moment, he looked a hundred. She killed someone.

When he said it, my mind went white, a faint whooshing in my ears like a TV tuned to a static channel. And we both felt it, the inevitability of finally colliding with the train rushing toward you. This day was always going to come, of course, and we had always known it. We could have ended it years ago, should have ended it, if only we’d known how.

I had asked who, and how, and Pop’s voice had measured out the words, parsed into bits, which meant he didn’t have all the details, but what she did was more horrible than he’d wanted me to know. He said she’d stabbed a woman, but you know she’s out of her head most of the time, right, Edie? It wasn’t her; it’s not her that did this thing. Which is what he’d always said when she “went away.” When she seemed to turn into a wholly different person, if someone can be a different person when, in fact, they’re a different person all the time. I wanted to shake him and say of course she did this thing, it’s her, it’s always her, you just never see it. To see it, to fully see it, he’d have to act on it, which we did not do.

Which is why, despite what various psychologists have insisted, I realized at fifteen—we all killed a woman.

But I went to school that day. I guess I shouldn’t have. I was late, skipped second period and instead sat in the library, at a computer terminal in the back, and read the news.

“Woman, 34, Arrested for Murder.” It was short. Mentioned Lilith by name, the victim was nameless. Lilith stabbed her.

I remember the library was hot. It was June and the school didn’t have air-conditioning.

I remember how the smell of the cafeteria hit me when I walked in: warm bread and hot onions and always the queasy undertone of bleach.

“Why are you here?” Mia asked, her voice cut with a razor, her upper lip curling.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” No one moved over. I was still standing when I realized the cafeteria had gone silent. Even the teachers stared at me with bright, white horror. “It’s not true.” It felt good to say, like it could be true, but how do we know what really happened? People get accused of murder all the time and then get exonerated. I feel a sweeping, vertiginous relief. Of course. Why hadn’t I thought of this earlier? It was a mistake. “We don’t know the full story, my dad is going to find out today. I know the papers say she killed a woman, but—”

“Four,” Mia said, her voice throaty and indistinct. “She killed four people, Edie.” She almost laughed, halfway between a bark and a yelp, her red fingernails digging into the white bread of her turkey sandwich, still in her hand but wilted and forgotten. “Lilith Wade is a fucking serial killer.”

Later, the number would increase to six. Later, it would be obvious there was no mistake. But in that moment, there was only the quiet and the word killer bumping up against my brain, sticking in my throat. Nothing would ever be the same: it was palpable. Every slumber party— those precursors to intimacy, where adolescents practice love—I’d skirted confessions about Lilith; like the time she picked me up at school, driving her car before she lost her license, in just a pair of jeans and a bra (What? It’s just like a bikini top.), or the time in the woods with the gun when Dylan saved us. Any chance I had at someone else knowing these stories, knowing me, was gone.

I looked at my friends, at Mia’s little, upturned nose, her blond, wavy hair, her bright blue eyes, and Rachel’s dark, almost black hair, with the purple streaks I’d put in there myself the weekend before. I looked at their eyes and saw only fear.

* * *

In the dead of night, the phone rings and the display says Dylan. I answer it, garbled and bleary, and he says, Edie-Bee, are you there? Were you sleeping? Of course I was sleeping. I don’t say this, but instead feel myself drifting off, the Restoril pulling me back into the black fog of unconsciousness. I hear him talking. My brother, plagued with our shared insomnia, which he’s afraid to medicate but I am not, while he rambles the house, waking his wife and son, alternately exhausted and manic. I had an idea