Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

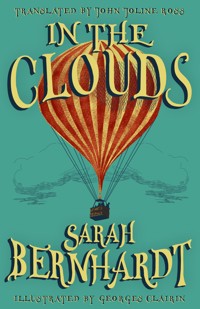

In 1878 Gustave Flaubert looked on in horror as his publisher picked up a manuscript from the mysterious stage actress Sarah Bernhardt and published it in place of a new edition of his latest work, and watched it go on to become an instant bestseller, achieving international fame. Narrated by a chair in a hot-air balloon, In the Clouds is a light-hearted, humorous tale that follows a character reminiscent of Bernhardt through the skies above Paris. Sadly the story sunk into obscurity, lying out of print in the English language for much of the twentieth century. Featuring the original illustrations by Georges Clairin, and in a fresh edit of the first English translation, this edition seeks to bring the tale to a new generation of readers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 69

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In the Clouds

The Impressions of a Chair

sarah bernhardt

illustrated by georges clairin

translated by john joline ross

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

In the Clouds first published in French as Dans les nuages in 1878The basis of this translation first published in 1880

Translation, text and notes © Renard Press Ltd, 2021Extra Material © Renard Press Ltd, 2021

Cover design by Will Dady

The pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or are presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain their copyright status, and to acknowledge this status where required, but we will be happy to correct any errors, should any unwitting oversights have been made, in subsequent editions.

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

contents

In the Clouds

Notes

Biographical Note

in the clouds

to monsieur henry giffard

from two grateful artists

sarah bernhardt

georges clairin

My straws were born in a modest field near Toulouse, and my back and legs were taken from a little ash tree in the forest of Saint Germain.

My thoughtful, dreamy nature was forever transporting me into the highest regions.

I longed for luxury, for travel; I envied those gilt chairs whose feet rest on oriental rugs. Being an official chair would have been the delight of my life. The furniture-movers’ vans* made my heart beat fast when I saw them driving through the street, loaded down with furniture and chairs which were being carried away to be transported across the seas.

Happy chairs!

And I cried in silence while I hung upside down from an iron bar near the ceiling of a little shop, my tears trickling down, drop by drop, making the gas jet below me crackle.

‘What nasty wood!’ said the grumbling old dame, the owner of the little shop.

It was a Tuesday. A stout gentleman walked into the shop.

‘I would like some chairs,’ he said. ‘Some cheap chairs.’

It appears that we were cheap, for the shopkeeper displayed twenty-four of my companions.

‘That’s your affair,’ she said. ‘How about these?’

‘Very well,’ said the man, ‘but I need more.’

The grumbling old dame showed him thirty more.

‘Here is all my stock. Ah! There’s this chair too – but I warn you, for I never deceive my customers, it is made of bad wood. The wood is green – it cries all the time!’

‘Give it to me anyway,’ said the man.

So, here I am, taken away in a big wagon. I traverse many streets, and after that a grand boulevard; the wagon enters an immense courtyard and stops in front of a gate.

We were unloaded from the wagon, and two days later we were placed three by three around marble-topped tables, on which were placed women’s portraits and advertisements for pharmacists.

I watch; I listen. I am, it appears, in the courtyard of the Tuileries,* which has become the home of the captive balloon.

‘What luck! A balloon!’ I saw a balloon, and it was the very largest that had ever been constructed. And then there was a great machine that kept going, going, going all the while. It seems all this was quite superb, for I heard very competent men around me saying, ‘It’s admirable! Giffard is a truly remarkable man – what a genius organisation!’

I was proud. I didn’t know Monsieur Giffard, but that didn’t matter – I was proud, all the same. There were people here and there who criticised the cable, the basket, the steam engine, but I quickly came to understand that these detractors were cowards, who made themselves critics because they couldn’t be actors.

I laughed behind my straws at all these little weaknesses! One of them said he wouldn’t go up because he wished to preserve a husband for his wife; another a father for his children; a third because he was dizzy! And so on – a thousand dull pretexts.

However, I was there for eight days, and the crowd increased with every ascent. Ah! How I would have liked to go up in the balloon too! But no, the passengers always stood up in the basket, so there was no hope for a poor chair.

I was deep in thought one day, but was drawn out of my reverie by the conversation of some men nearby.

‘Who are you waving to?’

‘Doña Sol.’*

‘Ah! Point her out to me – I don’t know her.’

‘She’s coming over.’

I looked over, and I saw, advancing slowly, surrounded by lots of people, a young woman, rather pale and thin. She held a little cane, and was speaking terribly fast. She went up in the balloon, and then, after the ascent, came and sat down very close to me. She was in raptures – she would come again the following day, and every day, every day! This pleased me greatly – I would very much like to serve as her seat.

In fact, she did return, and went up in the balloon two or three times each day. I found that a little much. Everybody else seemed to agree with me, and they told her so.

‘My chest hurts a little,’ she replied, ‘and I breathe so much better up there!’

Her voice was so charming that I instinctively agreed with her; but it’s a wicked and sneering world, and I heard my young friend criticised, defamed, slandered. I was enraged because I was powerless to come to her defence.

One day a stout gentleman, accompanied by an even larger lady, was unsparing in his abuse – she was a poser, desperate to be the centre of attention, she had no talent as an actress – there was someone unknown who voiced her roles, and she merely mimed! It was a poor sculptor, dying of hunger, who made all her statues in hiding – and as for her paintings, everyone knew they couldn’t be her work, for she had never even held a brush! That was clear, huh? And they both shook with laughter at this brutal pun.* I jumped in anger, and upset the stout gentleman, who, furious, got up off me, took me by the shoulders and threw me to the ground violently.

‘What a horrible chair! It would scarcely support Doña Sol!’*

‘Wait – that’s an idea!’ exclaimed Louis Godard,* who was passing by at that moment. ‘It’s light – we can take it with us tomorrow.’ And, picking me up, he examined my limbs to make sure that the brute hadn’t broken any part of me. Then he carried me into a large hangar.

‘Leave this chair here,’ he said, placing me in a corner. ‘Doña Sol will use it tomorrow.’

I remained in a reverie. What did it all mean? Tomorrow? Doña Sol? What will happen tomorrow?’

All night long I watched women squatting on the ground beneath me, working on a large piece of orange-coloured fabric, the shape of which I couldn’t make out. They spoke about ‘tomorrow’, but all I caught were snippets of their conversation, which only piqued my curiosity without satisfying it.

Finally day broke: it was again a Tuesday. I had dozed off somewhere towards morning. Men coming to collect the orange fabric rudely awoke me, and one of them, taking off his jacket, threw it on me. I could no longer see anything. I could hear them coming and going, but I couldn’t understand what was going on. I suffered greatly. The owner of the jacket returned, perspiring heavily, to collect his clothes. I opened my straws wide.

Oh, surprise! I see a great round, soft thing, the shape of an immense mushroom. It springs from the ground, stretching and widening out towards the sky, and the mushroom swells upwards, ever upwards!

Finally it rises from the ground, held down by some ropes. It’s a balloon, a tiny orange balloon. It curtsies to the huge balloon, which wobbles like an elephant.