5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ROWOHLT E-Book

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

"The I of my heart says hello to the you of yours." The year is 2264. Despite incredible technical advances, scientists of the twenty-third century are at a loss on how to solve the problem of a decimated human population. The young historian Finn Nordstrom, a specialist for turn-of-the-millennium popular culture, is asked to translate newly discovered diaries written in extinct German. Do the vintage diaries of a young girl from the early twenty-first century hold a secret that can revitalize humankind? Finn Nordstrom lives in a passionless but otherwise worry-free and peaceful world shaped by community spirit, leaps in science, and the promise of immortality. All is well until he begins decoding Eliana's diaries. Following the progression of her life from page to page, he becomes fascinated by the young girl blooming into womanhood right before his eyes. Asked to test the authenticity of a virtual-reality game set in the twenty-first century, Finn is stunned to find himself face-to-face with the girl. Caught up in a whirlwind of intrigue orchestrated by powerful physicists, Finn is sent unwittingly on a dangerous mission through time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 531

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

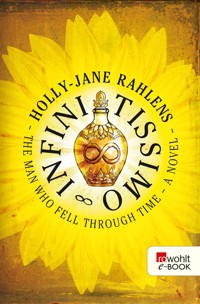

Holly-Jane Rahlens

Infinitissimo

The Man Who Fell Through Time

A Novel

Über dieses Buch

“The I of my heart says hello to the you of yours.”

The year is 2264. Despite incredible technical advances, scientists of the twenty-third century are at a loss on how to solve the problem of a decimated human population. The young historian Finn Nordstrom, a specialist for turn-of-the-millennium popular culture, is asked to translate newly discovered diaries written in extinct German. Do the vintage diaries of a young girl from the early twenty-first century hold a secret that can revitalize humankind?

Finn Nordstrom lives in a passionless but otherwise worry-free and peaceful world shaped by community spirit, leaps in science, and the promise of immortality. All is well until he begins decoding Eliana’s diaries. Following the progression of her life from page to page, he becomes fascinated by the young girl blooming into womanhood right before his eyes. Asked to test the authenticity of a virtual-reality game set in the twenty-first century, Finn is stunned to find himself face-to-face with the girl. Caught up in a whirlwind of intrigue orchestrated by powerful physicists, Finn is sent unwittingly on a dangerous mission through time.

Impressum

The work on this book was supported by a grant from the Stiftung Preußische Seehandlung, Berlin.

“Infinitissimo – The Man Who Fell Through Time”, written in English, was first published as a German translation under the title “Everlasting – Der Mann, der aus der Zeit fiel” by Wunderlich Verlag, Reinbek

Copyright © 2012 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg

Copyright English edition © 2017 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg

Umschlaggestaltung Hafen Werbeagentur, Hamburg

Umschlagabbildung Nico Reitze de la Maze; Alkestida/Shutterstock; cg-textures

ISBN 978-3-644-40410-6

Schrift Droid Serif Copyright © 2007 by Google Corporation

Schrift Open Sans Copyright © by Steve Matteson, Ascender Corp

Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt, jede Verwertung bedarf der Genehmigung des Verlages.

Die Nutzung unserer Werke für Text- und Data-Mining im Sinne von § 44b UrhG behalten wir uns explizit vor.

Hinweise des Verlags

Abhängig vom eingesetzten Lesegerät kann es zu unterschiedlichen Darstellungen des vom Verlag freigegebenen Textes kommen.

Alle angegebenen Seitenzahlen beziehen sich auf die Printausgabe.

Im Text enthaltene externe Links begründen keine inhaltliche Verantwortung des Verlages, sondern sind allein von dem jeweiligen Dienstanbieter zu verantworten. Der Verlag hat die verlinkten externen Seiten zum Zeitpunkt der Buchveröffentlichung sorgfältig überprüft, mögliche Rechtsverstöße waren zum Zeitpunkt der Verlinkung nicht erkennbar. Auf spätere Veränderungen besteht keinerlei Einfluss. Eine Haftung des Verlags ist daher ausgeschlossen.

www.rowohlt.de

For Noah, his friends, their future …

Note

Infinitissimo was written in 2265 in Late North American English (LNAE). The enclosed adaptation into turn-of-the-millennium American English, ca. 2000–2040, was executed as “Required Adaptation Exercise 6” for the seminar certificate “Understanding the Life Stages of Language – English, Part III.” Some foreign-language references have been left in their original when adequate equivalents could not be found. Knowledge of extinct German is helpful but not a requirement. I am much indebted to my mentor, Dr. Nelhar N. Suiled, for his assistance in elucidating the meaning of several obscure passages and words.

Bella Tema Mo Wald

Department of Historical Languages

European University, Berlin

June 4, 2450

Chapter OneThe Island

Finn slipped the Moon Zoomers on over his eyes. Above him, the deep night sky glittered faintly. He made out a space racer bringing workers to Mars and beyond. Or maybe it was back home for the holidays? It was hard to say from so far away. But he could see the racer’s floodlights blinking, perhaps greeting that SunTeam cruiser, booked full, he presumed, with bungee jumpers out for a cosmic thrill. Finn shuddered at the thought. He’d never been fond of those weightless free falls.

Far below, the 11 p.m. sky-glider from town came coasting along, closer and closer. It looped soundlessly landward and soared over Finn before alighting at the Outer New York Metroport to the north, behind him, all the way across the bay.

And the sea rumbled on. The waves rolled in. Then out. Back and forth. The water rose. And fell.

The air was still heavy with the past day’s September heat, with salt, sea spray, and his neighbor’s jasmine. Finn thought he might fall asleep, right there on the beach, under the stars – that’s how tired he felt. But then a crab scuttled past his bare foot. And then another. Something had alarmed them. Alert, Finn heard soft steps in the sand. The rustling of fabric. Someone was approaching. He twisted around.

“Oh!” Rouge gasped, startled, but a moment later she let out a laugh. “Finn! What on earth are those things? They’re frightening!”

Finn rose, pulling the Moon Zoomers over his head, careful not to stretch them out of shape. “Rouge,” he said, taking a step toward her. “Sorry. Your visit is so unexpected.”

Rouge dropped her sandals to the sand, and they air-kissed to the right, to the left, to the right of their cheeks. But there was awkwardness between them. Finn was not one for surprises, even one as stunning as Rouge Marie Moreau, so elegant, so lithe, a long-stemmed rose on this quiet strip of Fire Island beach.

“It’s not easy getting in touch with you,” she said, whisking a few strands of hair from her eyes. Ah, those eyes, steely green and so keen. They never miss a thing. “Is something wrong with your Brain Button?” In the moonlight her curls glittered metallic red, like copper.

Finn shook his head. “No. It’s off. Everything’s off for a few days.”

“Everything?” she said.

Finn detected a subtle, seductive lilt in her voice. They’d once been a couple. The affair had ended almost as soon as it had begun – Finn had felt that they were ill-suited as partners, but they remained friends and even unit-mates. Recently, though, Finn had sensed a delicate shift in her affections again. Or was it just his imagination?

Rouge smiled up at him. And Finn returned it – albeit with a shadow of reluctance. She intuited his hesitancy. “What are those things?” she asked instead. The lilt in her voice was gone now.

“Moon Zoomers.” He was glad for the change of subject. He repeated the name, more slowly this time – “Moon Zoomers” – clearly enjoying the internal rhyme. Rouge, though, didn’t seem to notice. “They were Mannu’s,” he went on. “A gift from our father. He found them in an antique store. Years ago. They were in one of Mannu’s drawers.” Finn handed them to Rouge, indicating an inscription on the inside of the frame. “See? It says, ‘Made in USA.’ So they were certainly assembled before 2105. Our father thought 2040 or so.”

“Hmm,” said Rouge, contemplating the clumsy-looking goggles. “That makes them two hundred twenty-five years old. Manufactured right in the middle of Dark Winter.” She turned the goggles around in her hands. “More than half the world’s population was dying, and the Americans were still looking for new worlds.”

“It makes sense,” said Finn, with a slight edge to his voice. He often found himself, especially with Rouge, in the unpleasant position of defending his native continent. He liked to consider himself a European continental, but there he was championing the North Americans. “They thought it was the end of the world. Why not look for new ones?”

“Touché,” she said, and then returned to the object itself. “Do these things still work?” They were dangling from her fingers like a dead mouse by its tail. And that was exactly how she felt about them.

“Yes,” he said. “More or less. But only to a maximum distance of four hundred thousand kilometers. There was a space racer near Alpha Sextantis a few minutes ago. But it was hard to tell if the racer was coming or going.”

“But we see so much better with our BB telescope applications. With Skyze, C-Stars, AstroVu, and –”

“Rouge, it’s just for fun!” he said, as always mystified by her lack of humor. “It was a toy.” He smiled at her. “Would you like a try?”

She shook her head. “No. Thank you. No.” She looked up at the night sky.

Finn wondered a moment if she felt insulted, but realized she was just trying to locate the space racer with her Brain Button. “Do you see it?”

“Yes,” she said, after just a few moments. “There it is.”

Finn was impressed. Rouge was by far the fastest BB-impulse carrier he knew. Brilliant, really.

“It’s coming home. It’s moving toward us,” she reported, and then looked back up at Finn, waiting for his eyes to meet hers. “How are you?” she asked, when they had.

He inhaled deeply then looked out at the sea. She waited quietly at his side while he searched for an answer.

“It’s been difficult,” he said, finally. “Especially losing Lulu and Mannu. We were so close. All three of us. Our parents were always working, so when Lulu was a young child, we weren’t just her big brothers. We were also her caretakers. She called us Manny and Fanny.”

“Fanny?” Rouge said, amused. “It doesn’t quite suit you.”

Finn shrugged, and then looked down at his foot where his toe had found a stone. He picked it up and a dragonfly materialized from under it. “Oops! What’s that doing there?” he said, startled, following the flight of the creature in the dim moonlight. The dragonfly circled around them, its phosphorescent wings fluttering wildly, then it flew away.

Finn turned to Rouge. “Lulu used to try to catch them when she was little. She squealed like a wild piglet when she ran after them. The house is too still without her now. She was quite the chatterer. Yakety-yak the whole day through. Like so many teenagers.”

“‘Yakety-yak’?” Rouge asked, unfamiliar with the word. She would have no trouble finding its meaning almost immediately with her BB, but she knew Finn enjoyed throwing tidbits of trivia her way, and then enlightening her about them.

Finn smiled. “North American, circa 1950, to talk persistently. From the verb ‘yack,’ origin unknown. Possibly imitative of the sound of chatter.”

Rouge’s English was impeccable, but her knowledge of historic North American slang was rudimentary, as was the case with most hard-core scientists from the European continent that Finn knew.

“Yakety-yak,” she said, amused. “It does sound like chatter.”

Finn’s eyes returned to the sea. “Lulu will be missed. Sorely. They will all be missed.” He looked at the stone still in his hand, and then tossed it. He watched the distorted reflection of the moon on the surface of the water ripple as the stone skimmed the surf and then disappeared. He turned to Rouge. “Mannu was quite the stone thrower. We used to stand here and see whose stone skipped the most in the water. He always won.”

Rouge waited for him to continue.

“He used to make a big show out of it,” he said, still looking at the moonlit sea. “All the girls would gather around from up and down the beach, and he would take off his shirt – all those muscles popping, all that curly hair climbing up his chest – and then he’d toss the stone, and it’d skip ten, maybe fifteen times if the surface of the water was smooth. And the girls would all swoon.” He looked up at Rouge. “He was a hard act to follow. But he was adored. Unconditionally.” Finn attempted a smile, but then abandoned it and bit down on his lip. “Twenty-one is too young to have lost one’s entire family. All four of them. Gone. Just like that.”

Finn heard Rouge inhale deeply through her nose.

“An orphan,” he said, indignantly. “Finn Nordstrom, an orphan.”

Rouge put a hand on his shoulder. Finn felt its warmth through his thin top.

“Should we go inside?” Rouge asked.

“Let’s sit out here a bit.”

Rouge was wearing a light summer dress, gauzy, with shimmery blue-and-green filigree. It was cut low, so her décolleté was on show in the moonlight, her breasts almost spilling out of the bodice. He noticed a perfect brown dot on the pale skin above her right breast. Had he just never noticed the birthmark before, or had she recently had it created especially for a night like this? He looked away.

Rouge lowered herself to the sand, tucking the fabric of her dress under her. She stretched out her endlessly long legs, and then neatly folded them back up under her. She did this with such grace and economy of movement, Finn was reminded of those antique folding knives from Solingen exhibited in the Museum of European Culture, not far from where he lived in Berlin. Fascinating, the way her legs snapped open, and then snapped shut. Zzsscchht.

Rouge and Finn looked out at the sea.

Finn smiled inwardly. What a comparison – likening Rouge’s legs to a switchblade! But then again, Rouge had always had something dangerous, almost predatory, about her, as if she were on the verge of luring him into a trap, snatching him up with those long limbs of hers, and then eating him alive.

“You’re smiling,” she said.

“What actually brings you here?” he wanted to know.

“It’s a favor. For your university.”

Another surprise for Finn. “Greifswald? They asked you to come? Here?”

“They’re anxious you might give up your job now. And return to North America.”

“They should be anxious!” he said. “These past three months have been driving this translator bonkers!”

“‘Bonkers’?”

“It means crazy. Mad. North American, 1940s, origin unknown.”

“Spelling?”

“B-o-n-k-e-r-s.”

“Bonkers,” she said, pausing a moment, as if looking in a mirror and trying the word on for size. “And?”

“They have us proofreading the punctuation on the computer-generated translations of those bank business reports they discovered a couple of years ago. Proofreading! You’d have thought those applications would know grammar by now. And they’re so boring!”

Finn was frustrated with his university job at the Library of Europe in Greifswald. He was a skilled translator of two languages into his English mother tongue – extinct German and New Standard Mandarin – a specialist in the decoding of German-language handwritten documents, as well as a highly trained but under-challenged historian for popular culture in the pre-Age of Dark Winter (1950–2029). “They should be giving us great works of literature to work on,” he said, “not Deutsche Bank’s ‘Consolidated Statement of Recognized Income and Expense for the First Quarter 2021.’ That stuff can be left to artificial intelligence. Who cares if there are punctuation errors?”

Rouge laughed – but kindly. “You’re a junior historian, Finn. A student! That’s your job.”

“And you are a junior physicist. But are you asked to sit under a tree and wait for an apple to fall on your head so you can theorize about gravity?”

Rouge laughed again. It was very easy to amuse her sometimes. If his BB weren’t turned off, he’d jot the joke down. Now he might forget it.

“But everyone said the business reports were a world cultural treasure,” Rouge said.

The reports had certainly caused a sensation when they were excavated four years ago, in 2260. They were discovered fifty meters under the earth at the site where the bank’s main headquarters in Frankfurt once stood. The archaeologists found fewer than thirty cubic meters worth of metal file cabinets stacked with German-language business reports, but that they had even survived the Great Scorching of 2050 was a miracle. It rid Europe of the German Plague, yes, but unhappily it destroyed most of its culture along with the virus.

“Those bank reports, a world cultural treasure? Please!” said Finn.

“Fine, fine,” she said, leaning back on her elbows and looking up at the stars.

Finn leaned back too. “But Greifswald surely didn’t send you from Berlin to a sleepy New York beach community just because they’re anxious about losing a junior historian with translation skills.”

“Correct,” she said, stretching out her legs.

“So why have you come?”

She turned to him. “Baltic archaeologists in Stralsund found something on the Fischland-Darss peninsula.”

“Found something?” he said, sitting back up.

“A case. Airtight and watertight. Corrosion-proof. Dust-proof. Everything-proof. The kind used on boats in the early twenty-first century. It was on the floor of the Saaler Bodden near Wustrow.”

“At the bottom of the Bodden?” Finn thought he might laugh. How absurd! The Bodden was so shallow. And unspectacular. It was not anywhere near a deep sea where one imagined ships and their treasures were buried.

The Bodden landscape – a string of saline lakes with a sea connection along the southern Baltic coast, once a sanctuary for migratory birds and a nature preserve – suffered greatly during the Age of Dark Winter. But now that most of Europe had been resettled, some of the Baltic coastal areas were being reorganized into sea-mining communities.

“But those waters are so shallow,” Finn said. “You’d think that everything down there would have been fished out by now.”

Rouge shrugged. “It’s at least six meters deep where they found the case. Apparently, it was down there for well over two hundred years. They came upon it by chance while prepping the area for construction.”

Finn’s heart began to race. “Is it an important find?” he asked, trying to control his breathing.

“A world cultural treasure.” The statement had a slight, very slight, mocking edge to it, so Finn wasn’t sure if this was what the experts were saying, or if it was just Rouge teasing him.

“Why? Is there something important inside it?” he asked.

“Possibly, they say.”

“And what does all this have to do with this historian?”

“There’s something in the case, Finn. It’s handwritten in German. It needs to be decoded and translated.”

“But why this translator? And why send you here? What’s the rush?” None of this made sense to Finn.

Rouge shrugged. “Perhaps they’re worried that one of the larger universities will snatch it away if they don’t act quickly. Obviously, they think you can do the job.” She looked up at him. “It may be what you’ve been waiting for.”

He tended to agree. Bank reports wouldn’t likely be at the bottom of a shallow saltwater lake. Especially not handwritten ones. But what would be there?

“Will you speak to Greifswald about it?” Rouge asked.

“Yes. Certainly. Of course.”

“Good,” she said, standing up. She wiped the sand off her hands. “The director of the Library of Europe expects your call. First thing in the morning.”

Finn rose too. “So soon?” He was clearly astonished.

“Even sooner than you think. His morning. That’s in –” She tilted her head slightly, accessing her BB clock. “Two hours.”

“In two hours?”

She nodded, and then yawned.

“You’re tired,” said Finn.

“Yes. Shall we go inside?”

They were standing close. So very close. He noticed the birthmark on her right breast again, how it rose and fell with her breathing. He could pull her toward him and kiss her.

But he didn’t.

“This way,” Finn said, turning away and pointing to the large wooden house to the west. “The Nordstrom residence.”

Rouge grabbed her sandals and followed him in.

Chapter TwoDoc-Doc

Finn tidied up the family den for the holocasting. The Library of Europe’s director might decide to pay him a visit. With Doc-Doc, as Dr. Dr. Rirkrit Sriwanichpoom was referred to by his employees – and not without some sarcasm – you had to be prepared for anything.

Finn parted the curtains. The moon, a fat white balloon, was floating in full view above a smooth Atlantic. A brilliant backdrop for a holocasting. Finn was aware of his growing excitement. What was in the Bodden case? Dare he hope for a “millennium miracle”?

The last great discovery in German was almost 130 years ago, in 2136, on the North American continent, in the province of California, in Laguna Beach. In a house of rotting stone and stucco, workers prepping the ruin for demolition found a worm-infested oaken chest containing a steel box. Inside the box was a stack of handwritten pages. Experts in the lost languages identified the language as German, written in the old German script used at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. Further study established that it was Nobel Prize winner Thomas Mann’s original Buddenbrooks manuscript.

The California Cultural Treasure Office put up a strong case to keep the manuscript in North America – Thomas Mann was a naturalized American citizen, they argued – but in the end it was bequeathed to the Library of Europe’s Archive for the Lost Languages, where, Finn agreed, it rightly belonged. These days, it was kept under lock and key, but a tru-replica of it was on display, and Finn had studied and read the tru-rep – not an easy task, as even paleographers specializing in German find old German Kurrent script extremely hard to decipher if one’s training has focused primarily on the later scripts.

Buddenbrooks, in any case, was truly a millennium miracle and quite a distinction for the translator entrusted with it. Maybe Finn would be lucky too.

On the way to the kitchen, Finn passed the steps to the lower level and saw that the light in Rouge’s room was off. For a moment he remembered how tired he was, too, but fatigue was not a trait that Sriwanichpoom appreciated. As Finn had never spoken more than a word or two with the director in his life, it would not be good to make a bad impression now. He made himself a zing to get his brain cells bouncing, and then returned to the den. He connected to the holo-camera, then sat down and waited for Doc-Doc’s call.

Dr. Dr. Rirkrit Sriwanichpoom was a dazzling personality. Everything about him blinded the beholder: his handsomeness, his silver-white hair pulled back in a ponytail, his bright ivory smile, his eyes, large and lustrous like Tahitian gray pearls, his brilliant intelligence – even his shoes were dazzling. His feet sported those new transparent glass-like half boots. He wore them snugly over sparkling silver socks.

Finn was immediately aware of Dr. Dr. Sriwanichpoom’s boots because when Finn was holocasted into the director’s office, nicknamed the Throne Hall because of its spaciousness, the director’s legs were crossed lazily on top of his desk. “Mr. Nordstrom!” he said, rising. He came forward, and Finn gave his superior his hand in greeting. There was nothing for Finn and Doc-Doc to shake hands with save air – a hologram is, of course, just a hologram, and not made of flesh – but they went through the motions anyway.

“Sir,” said Finn. “Good morning.”

“What time is it over there?” Sriwanichpoom spoke English impeccably, with that brittle nasal accent that the people of the British province were known to have, but which foreigners, like himself, had perfected.

“It’s … uh … two a.m.,” said Finn, knowing full well that Doc-Doc knew exactly how late it was. So why did he ask?

“You’re staying up a bit late, aren’t you?” the director said with a chuckle. He didn’t wait for an answer. “Please, sit down.” He pointed to one of those transparent suspension tables with four hassocks assembled around it. Finn, who’d never before been invited into the Throne Hall, whether live or as a hologram, needed a moment to acquaint himself with the room before taking a seat. He actually sat down on a stool in his family’s den, but such details were unimportant when being immersed in 3-D images.

The director tugged his white trousers up a centimeter, sat down, and crossed his legs. His glass boot was almost in Finn’s face now. “So. This won’t take long. You know where the case was found, of course?”

“Yes,” said Finn. “At the bottom of the Bodden.”

“Correct. Near Wustrow.”

Ping! A ping-blink went off on Finn’s BB grid.

“You just received two documents,” the director said. “Take a look.”

The first was an image likely taken from a boat. Finn saw water and a rather desolate strip of land, probably the Bodden shoreline. There was a group of poplars on the left, and in the background the ruins of a town, with a steeple.

“That’s where the box was found,” said Doc-Doc.

The second document was the image of a black box with a handle, similar to turn-of-the-millennium hard-shell suitcases.

“The diary was found in that case,” said the library’s head.

The ping-blinks disappeared suddenly from Finn’s BB.

“So sorry,” said Doc-Doc, frowning. “They self-destruct. A bug. If you need them again, just ask. So, where were we? Ah, yes. You know the diary was handwritten in German?”

Finn nodded.

“Unfortunately,” the director went on, “German is not one of this director’s specialties, those being Italian, French, Russian, extinct Dutch and Danish, of course English, and naturally his native tongue, Thai. This reader was therefore unable to do more than give the contents a cursory inspection. Very interesting, though. One of the archaeologists over here in Stralsund, a Dr. … hmm …” The director raised his eyes toward the window and clicked into his BB. “Yes, there he is. A … Dr. Beyer … an Age of Dark Winter specialist … well, he took a somewhat more in-depth look at the diary’s contents but felt under-qualified to judge the significance.”

“Why was that?” Finn asked. “When this translator was fifteen, he worked with Dr. Beyer at summer camp. Dr. Beyer’s an outstanding Dark Winter specialist.”

“But sadly not a specialist for turn-of-the-millennium popular culture. This document we have for you today is from 2003, written by a teenager.”

“Oh.” Finn registered immediately that he was disappointed. A document from a teenager? It was certainly no millennium miracle.

“You seem disappointed?” said the director. “Were you hoping for a millennium miracle?”

Finn was so surprised, he laughed. The director was notorious for his genius-like intuition.

Sriwanichpoom laughed too. “You’re ambitious, Finn Nordstrom. That’s good. Downstairs in the Archive for the Lost Languages they say that you’re an early twenty-first-century specialist and that you have an excellent feel for colloquial turn-of-the-millennium German and English, both of which will be needed for this project.”

“This translator is grateful for the chance to show his ability.”

The director stood up. “Here is what we have prepared for you. We made a tru-replica of the document. We know that you historians prefer to work with hard copies rather than digitized BB documents. Very sensible, too, when it comes to handwriting.”

“There was only one document in the case?”

“Have you forgotten our government’s axiom: ‘One step at a time’?” said the director, wagging his finger jauntily at Finn.

That was standard procedure. The Deutsche Bank business reports were given to him one by one too. Chronologically. Always chronologically. “But were several documents in the case?” Finn persisted.

“That is not for this director to disclose,” replied Sriwanichpoom coolly, almost haughtily.

Now that was not standard procedure. Translators were usually briefed on the length and extent of their projects.

The library’s director held Finn’s gaze a full few moments. Finn thought his eyes cold, even threatening. And Finn had the vague feeling that the director reminded him of someone. But who?

Dr. Dr. Rirkrit Sriwanichpoom rose and nodded at a wall. It slid open to reveal a bookcase. He went over to it and returned with a book. Its cover was pink. Very pink. A lurid pink. They used to call it hot pink. Or neon pink. An ugly, shiny, loud pink plastic. Or perhaps it was vinyl. Tiny red hearts were printed on it. Hearts and flowers and butterflies. There was a flimsy-looking lock on the book, too, with a small gold key in the keyhole, a thin satiny pink ribbon looped through it. Finn didn’t know what to make of it. He looked up at Dr. Dr. Rirkrit Sriwanichpoom. “What is it?” he asked.

“It’s a diary,” said the director. “Handwritten, of course.”

“A diary?” Finn said, surprised.

Finn had seen several old diaries. But none of them looked like this. Most were elegant, leather- or linen-bound. Some had the words “Moleskine” or “Filofax” printed on their covers or spines. But then he remembered that he had once seen a diary of Anne Frank’s that had a lock and key like this. The Holocaust victim’s original diaries were sadly all lost during Dark Winter, but two reproductions of her white, red and green plaid diary, reconstructed by craftsmen in 2002, were salvaged from the ruins of Amsterdam and now preserved in the Library of Europe.

“Who’s the author?” Finn asked.

“We don’t know. Some entries are signed with the letter ‘E.’ We think it is a girl.”

“A girl?”

“A very young girl. Thirteen, said Dr. … uh …”

“Beyer?”

“Yes. Apparently, it starts on the child’s thirteenth birthday.”

The diary of a thirteen-year-old girl from the early twenty-first century? This could hardly be great literature or a world cultural treasure. Unless, of course, these were the early ponderings of someone who later became famous? But what was the chance of that? It crossed Finn’s mind that it might be a mistake to give up the Deutsche Bank business reports.

“We hope the author’s name is in the text somewhere,” said the director, again intuiting Finn’s thoughts. “Perhaps we know of her later work. That will be your job, obviously. To read every word. Research every reference. Where does she live? Who is her family? Who are her friends? You will surely find clues within. And, we hope, very soon. We think this may be an important project. You might even be able to get a doctoral thesis out of it. You do intend to get a graduate degree?”

“Yes, certainly. This student was considering working first another year or two, tweaking his research skills.”

“Very well then.” The director stood up. “This is settled?”

Finn was taken aback. “Do you need an answer immediately?”

Doc-Doc frowned. “Yes, of course. Why else a holocasting?”

Finn felt overwhelmed. “In that case, yes. Yes, fine.”

“We booked you a seat for today, Tuesday, two p.m. New York to Berlin. The information is in your in-box. We expect you in Greifswald early Wednesday.” And then suddenly he was standing right in front of Finn, in the Nordstrom den. “Ah!” said the director, looking around at the furniture in the room. “How charming. Twenty-first-century American.” He walked to the window. “Brilliant view. Moon on earth.” He turned to Finn and gave him his hand. “Well then, Wednesday.”

Before Finn could even shake hands with the air, the director of the Library of Europe had disappeared.

Chapter ThreeThe Onyx Box

Finn awoke to sunlight peeking in through his window. He lay still in bed a moment, studying the playful movement of the shadows in his room and listening to the sound of the surf outside the house, how the waves rolled in. Then out. Back and forth.

He’d only slept a few hours. He was in overwhelmed mode: the death of his family only two weeks before, Rouge’s visit, the call from Doc-Doc, and now a new assignment – the pink diary. There was too much happening too fast. Hopefully, he’d have time to catch up with his sleep on the two-and-a-half-hour flight.

He thought he heard Rouge stir in the neighboring room. He rose quietly and went to the open door. But she was asleep, her breathing even. He watched her nostrils flare and contract, flare and contract, the brown dot above her right breast rise and then fall, rise and then fall.

Rouge was beautiful when she slept, like this, with the long curve of her shoulder lit by the early pinkish light that crept in through the shutters, with her breathing so even and her copper curls spread across the pillow like a crown of fire. Yes, at this moment, he could almost imagine her as his mate. Although –

No. Rouge could never be his mate. Their temperaments were not a match. Her mind was pragmatic, grounded by facts; his was fanciful, adrift with ideas. She did not care for the things he cared for, and he had not a clue as to what engaged her beside her work – of which he knew less than zero. Quantum physicists – “quamps,” the public called them affectionately – kept pretty quiet about their work, especially the ones like Rouge who worked for the prestigious Olga Zhukova Institute for Applied Physics. How could he bring up children with someone whose work he did not understand, whose thoughts he could not fathom, whose interests he could not share?

“You learn to do that,” his mother had said.

“You’re too choosy,” said his father.

“Sleep around some more!” was Mannu’s advice.

“Everyone finds his mate,” said Lulu. “Finn will too.”

But it was time. He was late. Sex was considered healthy and was encouraged from as early on as fourteen. It was hoped that most young people had either found a partner, or were assigned one, by age twenty-four. If Finn didn’t find his mate within a year or two, he’d have to apply for one. Many young adults were glad to be assigned a partner, where everything from DNA compatibility to sperm count to eating habits were tested, compared, and evaluated. Not that it much helped the drastic, almost-fatal plunge in fertility during the past two hundred years. Despite the prevalent practice of in vitro fertilization, the decline in births was a worldwide problem, especially on the European continent, where families like Finn’s with three children, offspring of the same parents, were the absolute exception. Couples were thrilled if they had one child, while the General Global Government would be happy if even one in three couples brought forth a child; presently it was one in five.

Careful not to wake her, Finn slipped silently past Rouge’s door and started up the stairs for the living room.

A ruddy sun was rising in the east, bathing the beach in pink. To the south, the Atlantic shimmered metallic gray, to the north, the Great South Bay lay still. Beside him, to the right, on the west wall of the room, stood the book cabinet his father had built and his mother had stocked. To the left of it, a mirror.

Finn looked in the mirror. He saw a young man, decent-looking though nothing out of the ordinary; a tanned body; medium height of two meters; dark, wiry hair, disheveled from sleep; two days’ worth of facial growth; eyes as black as the onyx box that sat on the walnut table.

Finn walked to the table. Articles from the house were strewn across it. Some of them he was planning on discarding or giving away. Others – like the black onyx box, Mannu’s Moon Zoomers, Lulu’s teddy, and his father’s slapback racket – he would take with him to Berlin to his apartment. His mother’s equipment case would stay here. It was a large wooden box that he had lugged upstairs from her workshop. He opened it, taking pleasure in the way it folded out on both sides like a staircase, each stair, or tier, a compartment with solution bottles and repair paraphernalia. The scent it gave off – a tart mixture of oils and chemicals – instantly transported him back to his childhood. He experienced a moment of drunken sweetness, as if he were actually a child again and exploring the treasures that lay within the box, feeling a deep wonder as he discovered the soft cloths for cleaning the books, some made of fabrics, like wool, that were rarely produced these days; the thread and yarn used for rebuilding book bindings; a bag of lint from a never-used papermaking kit; the dainty brushes for dusting the book pages; and a harsh type of paper with very fine grit to remove ink spots. “Sandpaper,” his mother called it. Something called an “eraser” helped rid books of gray lines from pencils. He remembered his mother showing him a pencil. “It’s made of wood and graphite, and people used to write with it,” she told him. She made a few markings with it on the inside of the box. “That spells Finn,” she said. “In capitals.” He couldn’t read at the time, but he remembers feeling proud. Those lines were his name!

Finn bent down over the wooden box to see if his name was still there. It was, though fainter than he remembered. He grazed the lines with his finger, and for a brief moment a hollow feeling overcame him and his eyes smarted. He knew he missed his mother. He missed his whole family. But the moment he felt the feeling, or formulated the thought, he swallowed it down. Public exhibitions of grief weren’t forbidden and certainly he could do as he liked at home, but bouts of emotion were usually considered disturbing, sometimes offensive and even destructive. It would be imprudent to dwell on it, especially with Rouge downstairs.

Finn sat down and booted up his BB. He’d gone online briefly for the holocasting with Doc-Doc but hadn’t checked his in-box for several days. He was bombarded with a slew of messages from his friend Renko Hoogeveen, a librarian at the Library of Europe. Finn found his tickets for the day’s flight, as well as the Bureau of Aeronautics’ account of the space accident that had caused his family’s demise. He was supposed to be on the flight too but missed it due to work. What irony! Thanks to the Deutsche Bank business reports, he was now the last living Nordstrom of Fire Island.

Finn felt something dark and unpleasant rise again within him – but then he heard movement in the house below. Rouge was awake. She’d want breakfast. He went to the kitchen.

He would have to ask Chef Carlo Canelli-NY-FireIs3 to prepare fresh food for lunch. Perhaps lobster? Or whale from the East End Sea Ranch? Shark, though, is more like Rouge, he thought, smiling to himself.

He looked across the bay. The sky over Long Island was cloudless. He popped into his Brain Button’s C-Earth application and found that the skies farther east were clear too. It would be a good day for flying, he thought, as he mixed two ice-cold berryolas. He put one in the refrigerator and took the other with him to the walnut table.

According to family lore, Finn’s paternal forebear, Florian Lawrence, built this table with his own hands. Over the centuries, it had been handed down to the eldest child of each generation, from the Lawrences to the Scheinwalds to the Sopranos and then on and on to the Nordstroms.

As legend goes, Florian Lawrence survived the chaos of Dark Winter by fleeing Europe with his family on a boat from Germany’s Baltic coast to Sweden. From there he made his way by water to Norway, then Iceland and Greenland, to finally arrive in Canada, the sole member of his family to survive the trip. Unbeaten, he traveled south along the coast, eventually found a wife, and settled down. At some point he built this table. Over the centuries, it had become a symbol of his family’s survival.

The table’s design was simple, classic really, straight lines and a thick slab of dark, almost black, walnut wood. But its decoration was unique. In each corner of the table, a sunflower had been hand-painted, its head the size of a small plate, its stem running down the leg. At the very center of the table was a sun. The table was also singular in that it had a hidden drawer that pulled out from under the tabletop. In this drawer had been, as long as Finn could remember, the one thing that had survived the flight from Europe with Florian: the black onyx box.

Finn picked up the box.

It was rather small, not longer than his hand. Both bottom and top were flawless black onyx with a mirror finish. The top was decorated with a sunflower inlay.

Finn opened the box. Inside, lying on a cushion of black velvet, were a fountain pen and a ring.

A large translucent amber stone of remarkable quality, bright yellow, was mounted on the silver ring and set within a circle of tiny opaque black gemstones – obsidians. Trapped in the amber was a big, fat, perfectly formed and intact bumblebee. Engraved on the inner surface of the silver ring was the date 05.20.2018.

Finn lifted the pen out of its velvet bed. When he was a child, he remembered being intrigued by it. Pens were obsolete, and had been for over one hundred fifty years. Who wrote by hand anymore? No one he knew. It was even more archaic than keyboarding. You might still find a keyboard or two being used in some out-of-the-way rural districts, but even in the wilds, Brain Button signaling and imaging were routine for most everyone past the kindergarten years.

Finn’s fingers brushed over the stars embedded in the pen’s polished black grip. There was hardly another such item outside of a museum or a Forester colony gift shop. Except for museum curators, the only people who had any real use for pens, pencils, and crayons – let alone related antiquities like graphite and inks – were Foresters, who to most people were odd enough to be generally dismissed as museum pieces themselves. Foresters lived simply, dressed plainly, shunned most modern conveniences, and schooled their children themselves. Their colonies – extremely tight-knit communities that had little contact with the outside world – were few and far between: four to six on each continent. Finn’s parents, because of their work, had nurtured close ties to Foresters, especially to the Aaronson-Aiello clan, a family of printers and paper producers in Sternwood Forest, a Canadian Forester colony north of Toronto.

Finn regarded the pen in his hand. He couldn’t remember when he had last held it. He remembered it being heavier. But now its heft felt just right as it lay in his hand. He rolled it up and down his palm, admiring its sleekness and the sharp elegance of the nib’s fourteen-karat gold, platinum-plated point. His finger traced the inscription. He marveled at its cursive script, the letters joined. He couldn’t read the words when he was a child. In fact, very few people could read them. Cursive writing, like Egyptian hieroglyphics, was inaccessible to the common person. It had long since been replaced by computer-generated block letters.

True, some professions called for cursive reading. Librarians, archaeologists, museum curators, paleographic specialists, translators and historians often encountered handwritten documents in their line of work. These documents were usually scanned into handwriting applications that were more or less well-equipped to decode various types of script, taking into consideration style and individuality. Unfortunately, they gave inferior results in German. In order for these programs to work well, they needed literally thousands upon thousands of examples of good and bad handwriting. Only then could they figure out, as they went along, how to read a new type of highly individual handwriting. Sadly, Dark Winter had destroyed practically all of Germany’s handwritten culture. The applications simply did not have enough information to decipher documents with great accuracy.

For this reason, a handful of scholars were trained during their student career at deciphering handwritten documents in extinct German. Some of them achieved a measure of competence. Very few of them, however, were ever motivated to pick up a pen, place it on paper, and learn to write themselves. Finn was no exception.

Finn looked at the inscription on his ancestor’s fountain pen. Legend had it that Alisa, Florian Lawrence’s first wife, had given him the pen and had had it engraved. Over the years, some of the letters had disappeared, but it could still be read:

For F

In ev rla ti g lov

Y ur li

ugust 201

August what? It could have been any year from 2010 to 2019, but the rest was –

“Good morning.”

Startled, Finn twisted around.

It was Rouge. Of course. She laughed. “Daydreaming,” she said.

Finn couldn’t tell if the sentence was a question or a statement, so he just smiled. He noticed that her copper hair was mussed, but she had showered. Her silk robe, a dazzling royal blue, clung to her still wet body. There were water spots where the silk fabric was draped across her breasts. He could see her nipples, perfectly outlined, on the blue.

“You don’t have a sani-dryer,” she said, reading his look.

“No. Just towels. We Islanders have always been a bit old-fashioned.”

“What’s this?” she asked, reaching for the pen in his hand.

“The family jewels.”

She laughed. “A pen. How quaint. With diamonds.”

“No, not diamonds. Platinum. They represent stars.”

Rouge smelled the pen. Took off its cap. Tested the nib’s point with the pad of her index finger. Put the cap back on. She was very thorough. He supposed all quamps were like that over at the Olga Zhukova Institute. They had to be.

Rouge pointed to the inscription. “What does this say?”

“Some letters are missing. But it says, ‘For Florian, in everlasting love, Alisa. August two thousand something.’ Florian is an ancestor. Florian Lawrence. He managed to get out of Europe in 2029 by the skin of his teeth. Alisa was his first wife. They say she and their children died in Dark Winter. Of the virus.” He reached for the pen. “They don’t teach you how to read cursive at the OZI?” he added, teasing.

“The Olga Zhukova Institute teaches us how to think.” She must have realized that her reply sounded cutting, for she quickly added with a smile, “Reading is for daydreamers. And poets.” She handed Finn the pen. “‘In everlasting love,’” she murmured, rolling her eyes.

As a child, Finn remembered mulling over the words “in everlasting love.” He had learned in school that love led to egotism, jealousy, madness, misery, war. Why would someone want it “everlastingly”?

These days, Finn knew, of course, that misery and war were not necessarily a result of love gone sour. Their teachers in school had surely exaggerated. Nonetheless, the concept of romantic love – the kind he read about in nineteenth-, twentieth-, and early twenty-first-century novels at the university – was foreign to him and, for that matter, to everyone he knew. For the one hundred sixty years since the end of Dark Winter, humankind’s prime concern had been survival. Hard work for the good of all was a necessity. Procreation had become a duty – not, of course, that humans had become bonkbots reproducing solely for the good of society. Man was a social creature who cared for his fellow humans. He recognized the value of a balanced life, if not a life of grand passion. What did love have to do with it?

On the other hand, he had to admit that, at moments, he found romantic love undeniably intriguing.

“Finn?” said Rouge. “You’re daydreaming again.”

Finn looked at her. “Oh, sorry. Hungry?”

“Famished,” she said.

Finn noted that her voice had that seductive lilt to it again. He turned away and put the pen back in the onyx box.

Rouge picked up the slapback racket and contemplated it.

“Artu’s,” said Finn. “We used to play together.” The sound of his father’s name had a strange effect on him. His voice was dark, hoarse even. He swallowed hard. “He was an excellent player. When Mannu and I were young, he played single-handed against the two of us. ‘Artu the Unbeatable versus the Nordstrom Boys,’ he used to say. When we were fifteen and thirteen, we finally beat him. He was never so thrilled in his life.” Finn cleared his throat.

Rouge regarded him a moment, then said, “You have us now, Finn. The PAD is your family now.”

“Oh, please! You sound just like the PA manual!”

The PA manual was downloaded into everyone’s Brain Button on his or her eighteenth birthday. It was the day they officially became pre-adults in the eyes of the General Global Government. “Welcome to your new life as a pre-adult” was the opening remark; “those delightful years between eighteen and thirty, that time of your life when you are no longer an adolescent but do not yet have adult status. You know who you are and what you would like to become. You’re prepared to spread your wings, take flight, and join the ranks of the working population. It’s time to leave your family behind and find a new family in your designated Pre-Adult Dormitory. The PAD is your new home. Enjoy.”

That was only three years ago. Lulu had been a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl; Mannu was twenty and studying space law. Their mother was struggling with the restoration of a thirty-three-volume 1993 Encyclopaedia Britannica Deluxe edition, bound in soft padded leather and falling apart at the seams. Their father had recently expanded his antique shop with rare twenty-first-century natural wood furniture. And Finn was happily studying at European University Greifswald. EU Greifswald was one of the few universities in the world with an intact campus, a haven for free thinkers and creative spirits, where human interaction between students and mentors was favored over the prevalent use of artificial intelligence and remote access. It was just a fifteen-minute commute with the nonstop SwiftShuttleX, aka the “swuttle,” from Berlin, where he lived in the world’s largest PAD community. Situated in the trendiest neighborhood of the city, in the Märkisches Quarter, it was known affectionately throughout the world as the BAD PAD, the PAD with the most booze, the most action, and the most drugs, ergo: B-A-D.

Finn smiled at the thought of the BAD PAD being his big family now, a melting pot of ten square kilometers brimming over with the testosterone and estrogen from more than one hundred thousand young men and women from all seven continents, all on the run, all scouting for a mating partner, all working full-time in study or in training and looking to be entertained. Rouge and Finn inhabited a four-bedroom unit with two other PAs, Yolanda Abbas, a clone therapist, and a bicycle engineer, Severin Boxberg. Their home was one of the BAD PAD’s smaller structures, a three-storied villa under landmark protection that dated back to 2015. It had irregularly aligned windows and balconies shaded white, orange, red, blue, yellow, and green. It was called the “Rubik,” as it looked like an incomplete Rubik’s Cube, a puzzle game created almost three hundred years ago.

“Finn?” Rouge said softly, interrupting his thoughts. “Have you considered looking into memoclones?”

Finn shook his head.

She persisted. “When was the last time your family’s memories were downloaded?”

That information was probably now sitting in Finn’s Personal Info Bank. He hadn’t looked yet. “The Nordstrom family was never very conscientious about updating their memories,” he said. “And besides, Lulu was under age for memory transference. We only have her genome and her BB content.”

Clones, the basic ones, as well as the memos, were, as far as Finn was concerned, a problem. Problem – with a capital “P.”

Basiclones that developed naturally and came to term in a donor mother were generally considered healthy human beings. They were just twins – delayed by a few years. In the mid-twenty-first-century, basiclones were bred in series production to fight wars, and then later, once the Triple G – the General Global Government – had taken power, they were bred in series to rebuild the world. In the minds of the general public, they remained second-class citizens; eventually the Triple G weaned them out of circulation and put more effort into developing human-like androids without the emotional snags of humans. Basiclones were still conceived – under strict cloning laws – but they were brought up in normal conditions and their identities were kept confidential from the public. Nonetheless, at age eighteen, it was the law that clones be told their origin. They seldom dealt well with the information and suffered greatly under the age-old stigma.

Hailed as the first step toward immortality, memoclones, on the other hand, were an entirely different beast. A memoclone received its donor’s DNA just like a basiclone, but, in addition, it was the recipient of the donor’s downloaded memories. It was brought to maturation rapidly: A fully grown thirty-five-year-old memoclone took less than six months to mature.

Finn, like most Europeans over eighteen years old, duly had his memories downloaded during medical examinations in a painless procedure. The information was then transmitted along with current body measurements and organ data to highly secure neuro-vaults in the Swiss province, where it was stored, ready for upload upon the request of a family member.

Ideally, memoclones were supposed to be healthy, exact replicas of the donor more or less at the time of his or her demise or earlier. A husband who had lost his forty-year-old wife could very well ask for a memoclone of his thirty-year-old wife – or vice versa. In reality, their memories were spotty and they usually malfunctioned within five years, resulting in serious mental illness, aggression, and dull-wittedness. In the end, most memoclones were a burden to themselves or to the very people who had brought them into life. More often than not, they finished their days incarcerated in Clone Homes.

“No, Finn, they’ve come a long way with memoclones,” Rouge said. Her voice was kind. “Reynaldo Torres at the OZI says his wife is almost perfect.”

“Almost,” said Finn. “Almost, but not quite. And ‘not quite’ is not good enough. Besides, how long will she be ‘almost’ perfect? We’re talking about human beings, people we have ties to, people we care for. Also, how could a son or brother bring back one family member but not the other? A junior historian cannot afford three clones. And what about Lulu? We don’t have her memories. Forget it! It’s a preposterous thought.”

Rouge, somewhat shaken by Finn’s outburst, regarded him a moment, then put the racket back on the table. Her arm swept across the table. “World cultural treasures à la Nordstrom,” she said cheerfully.

Finn was relieved to move on to another topic. “Actually,” he said, “here are the real treasures.” He turned to the bookcase on the west wall and opened one of its dark glass doors. A blast of cool air filled the room.

“Oh, it’s chilly!” Rouge said.

“To protect the books.”

Rouge pulled one out at random, the slimmest volume, barely a hundred pages. The title was in block letters. “The Illeist’s Code,” she read aloud. Finn could tell that she wasn’t interested in the book, but she opened it anyway and he appreciated the gesture. “How old is it?” she asked.

“It’s one of the youngest in the collection actually.” Finn showed her the copyright. It was a reprint from the year 2107 of a book originally published in 2032. “It was a school textbook in North America and in Europe in the early years of Dark Winter,” Finn went on. “Schoolchildren had a hard time getting used to dropping the first-person singular pronoun.”

Rouge opened the book to the first page. “‘Introduction in Honor of the seventy-fifth Anniversary of Publication,’” she read aloud. “‘Illeism, or referring to oneself in the third person, was originally a practice prevalent in the United States Marines beginning in the 1930s. During boot camp, recruits were encouraged to refer to themselves as “this recruit” because it reduced individual identity and encouraged unit cohesion and cooperation.’” Rouge looked up at him. “Did you know that?”

“History 101.”

Rouge continued reading. “‘In 2029, when the German Plague reached the American continent, it was imperative that law-and-order troops across the country work as a cohesive whole. Not just the marines, but now the police, the army, the navy, air force, and the national guard adopted the principles of illeism in the hope of keeping their troops bonded so that they might more easily establish order across the nation. Surprisingly, it worked, and many other nations adopted the new illeistic code as well. Soon, it filtered down into colloquial speak and the pronoun “I,” especially in the Germanic and Italic subgroups of Indo-European languages, lost its importance. When the first General Global Government convened in 2105 and internationalism and global cooperation were emphasized, using “I” was considered a faux pas in polite society …’” Rouge’s voice trailed off. She was getting bored.

“It gives hints on how to get around using the first-person singular,” Finn said, showing her the contents page. “How to substitute a ‘we’ instead of an ‘I,’ how to form questions instead of stating a personal opinion. And the like. Things that are second nature to us today.” He took the book from her and slipped it back into place in the cabinet. He started for the kitchen. “You said you were hungry? A berryola?”

“Sure,” she replied, following Finn into the kitchen area, taking in the room’s northern light. “How did the call go last night?”

Finn shrugged. “This historian just hopes he’s doing the right thing. It’s a diary. From a thirteen-year-old. A girl.”

“Oh dear. That doesn’t sound very intriguing.”

Finn took Rouge’s berryola out of the fridge. “It might be. Would you like fish for lunch?” he asked. “We have a sea ranch across the bay.”

“Excellent.”

“Lobster? Whale?”

“How about shark?” she said.

Finn let out a laugh. “Bingo!” he said.

“‘Bingo’?”

“It’s what you call out when you win a game of bingo. It was also used in North American English as an exclamation to express satisfaction or surprise at a positive outcome. From the 1920s. Origin unknown.”

“But what was the ‘positive outcome’?”

“This friend guessed that shark would be exactly what you would choose to eat,” he said. “You are a predator, Rouge Marie Moreau. Everyone knows it.”

She laughed, took a sip of her berryola, and then said, “Who’s the prey?”

Chapter FourThe Iceberg

It was a bright morning and, as seen from the greenway, Greifswald was bathed in golden light. Everything smelled of last night’s rain, wet leaves, moist earth, the coming cooler fall autumn weather, and promise. Finn stopped at a kiosk and asked the robo-vendor for a bag of roasted almonds. A beep let him know that the collection sensor had locked into his BB banking account and withdrawn the price for the nuts. He continued on, realizing he was smiling. Indeed, his heart hadn’t felt this light in weeks. The prospect of a new assignment – a trophy job! – had lifted his mood. Today he would hold the pink diary in his hand – or rather, its tru-rep. He looked up at the Library of Europe.

Soaring skyward and dominating the Greifswald cityscape, the library was the only public collection of books in northwestern Europe, totaling seventy-two million items – a pittance in comparison to all that was lost. Built over one hundred fifty years ago at the site of the town’s fallen medieval dome, it was nicknamed the Iceberg. It certainly looked like one: all glass and mirrors, three hundred twenty-five meters wide at the bottom, sloping irregularly upward, and then spiraling higher and higher to ultimately form a pinnacle, one hundred twenty meters above sea level, dwarfing every red-roofed edifice in its vicinity. Inside, despite the glass, it was eerily somber and quiet: one’s footsteps echoed on the white marble floors; one’s voice ricocheted off the walls. Few people came to visit. And like icebergs, most of the Library of Europe was found below the surface – namely, underground, twelve stories deep. The last resting place for the books of Europe, the stacks, nicknamed the Catacombs, had been built to protect the encroachment of ever-higher water levels from real icebergs.