18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

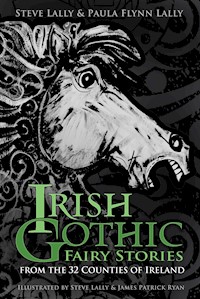

In the four provinces of Ireland there are thirty-two counties. Each county and its people have their own traditions, beliefs and folklore – and each one is also inhabited by the Sidhe: an ancient and magical race. Some believe they are descended from fallen angels, whilst others say they are the progeny of Celtic deities. They go by many names: the good folk, the wee folk, the gentle people and the fey, but are most commonly known as 'the fairies'. These are not the whimsical fairies of Victorian and Edwardian picture books. They are feared and revered in equal measure, and even in the twenty-first century are spoken of in hushed tones. The fairies are always listening. Storyteller Steve Lally and his wife singer-songwriter Paula Flynn Lally have compiled this magnificent collection of magical fairy stories from every county in Ireland. Filled with unique illustrations that bring these tales to life, Irish Gothic Fairy Stories will both enthral and terrify readers for generations to come.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Let us go forth, the tellers of tales, and seize whatever prey the heart long for, and have no fear. Everything exists, everything is true, and the earth is only a little dust under our feet.

William Butler Yeats

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO PAULA’S MOTHER AND STEVE’S FATHER,WHO ARE NO LONGER WITH US

CAIT FLYNN

(1947 – 2016)

PATRICK LALLY

(1945 – 1993)

ALSO IN MEMORY STEVE’S CHILDHOOD FRIEND WHO SADLY PASSED AWAY THIS YEAR.

MARK ‘JORDO’ JORDAN

(1973 – 2022)

MAY HIS MEMORY LIVE ON ETERNALLY AMONG THE SIDHE IN THE HOLLOWHILLS AND FAIRY MOUNDS OF IRELAND.

First published 2018

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL503QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Steve Lally & Paula Flynn Lally, 2018, 2022

Illustrations © Steve Lally and James Patrick Ryan

The right of Steve Lally & Paula Flynn Lally, to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9036 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

About the Authors

Foreword by Liz Weir

Introduction

‘Fireside Tale’ by Steve Lally

1 The Province of Ulster

2 The Province of Leinster

3 The Province of Munster

4 The Province of Connacht

How to Keep on the Right Side of the Sidhe

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

PAULA FLYNN LALLY grew up in Forkhill, Co. Armagh. From a young age she would pack her small bag with a notebook and pencil and go through the fields and find a nice tree and sit under it and write for hours. Paula is a singer-songwriter who once upon a time had a hit with a reworking of David Bowie’s ‘Let’s Dance’. She is now back in the recording studio. She is a graduate from Dublin City University, and when leaving was awarded the Uaneen Fitzsimons Award. She worked for a spell in radio. Paula has one album to date and is working on new projects, collaborating with other artists as well as studying to be a psychotherapist with the University of Ulster. She has recently put all her talents together (music, audio production and psychology) and is about to launch a new podcast called ‘Hold on with Miss Paula Flynn in Association with Minding Creative Minds’. Paula loves reading a good thriller, watching a scary movie and a decent BBC drama, and she loves nothing more than a good country song. She admires the work of Salvador Dali, Sean Hillen, David Shrigley, and Minton Sparks. She loves the poetry of Edna St Vincent Millay and Emily Dickinson and the music of The Carter Family, the Moldy Peaches, Gram Parsons and Nick Cave. The child inside her loves vintage doll’s houses and Blythe Dolls. She has a 7-year-old son called Woody who keeps her heart young. He is an aspiring writer who sells his books from a stand made by granddad Sean and uncle Micky Flynn at the front of the house. Paula loves her cats, going to the seaside, and spending time with Steve. She appreciates the darkness and the light and she believes in the fairies.

STEVE LALLY was born in Sligo, the Kingdom of the Fairies; he later moved to Dublin and then settled in Rathcoffey, Co. Kildare. This is where his imagination flourished, fired by the landscape, ancient sites and stories. As a teenager he developed a love of gothic horror literature, music and film, spending the long, dark winter nights reading Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft and writing stories with the music of Bauhaus and The Sisters of Mercy filling the night air. He is a graduate of Limerick College of Art and Ulster University. In 2021 he graduated with a Masters in ‘Social Practice and the Creative Environment’ (MA SPACE) from Limerick College of Art & Design. Steve is an international storyteller and successful writer who has already written and illustrated three books on folklore. His work is also part of an exclusive anthology of Irish Folklore.

Steve loves classic horror movies. He enjoys the work of Arthur Rackham, Harry Clarke, Jean Michelle Basquait and Neil Gaiman. He admires the poetry of Patrick Kavanagh and Patrick Mac Gill and the music of Einstürzende Neubauten, David Bowie, Nick Cave, Virgin Prunes and Planxty. Like Paula, he appreciates the darkness and the light, and he too has great respect for the ‘Good People’.

FOREWORD

Long before I became a storyteller I learned to have great respect for the ‘Good People’, those from the otherworld.

I grew up in Co. Antrim listening to the story of how my eldest brother encountered a banshee the night before the death of his friend’s grandmother. I had to walk home from school past the very spot where it happened but I was always careful never to do it after dark. This was a tale he retold to me before his death some sixty years after the incident, and it was as vivid to him then as when it took place. How could I have any doubt?

As a child I was brought up on stories of magic and enchantment. My favourite film was Darby O’Gill and the Little People, even though the pooka and banshee terrified me and the fairies were very tricky. Little did I know then that I would end up becoming a storyteller, based in the Glens of Antrim close to Tiveragh, a hill famous as a fairy stronghold. Folk in the Glens do not like to talk about the ‘other crowd’, as my friend Eddie Lenihan calls them, but they know better than to cut down a lone thorn tree or to give away milk or a light on May Eve. Although we live in a world where scepticism is rife, tales of fairies playing hurling still survive and those of us who live here are proud of the rich folklore of the area.

As I travel throughout Ireland sharing stories, members of the public regularly tell me their own tales of magical encounters. There are many cautionary accounts about what happened to foolish people who cut down lone thorn trees. I have even been asked for advice about building a house on a site with a fairy tree and on one occasion how to deal with one that blew down in a storm. Even references to people who are ‘away with the fairies’ refer back to tales of changelings that were left when human babies were stolen from their mortal homes. So, even in our hi-tech world, stories of the otherworld are still being told.

It is therefore very appropriate that we now have a collection of tales of the good folk gathered from every county in Ireland. This is no light-hearted Disney-like account of flittering winged creatures; these stories have been collected with respect by two people steeped in tradition. As an author and storyteller Steve Lally has proven his dedication to folklore, not simply by preserving the tales but by performing them to audiences of all ages. His co-author and wife Paula, a talented singer, grew up in the Ring of Gullion, an area of outstanding natural beauty, rich in mystery and fairy lore. By combining their talent and background knowledge they present a very readable collection, which will give a greater insight into the magical world of Irish fairies.

Liz Weir, MBE

Storyteller and Writer

INTRODUCTION

Over the centuries such folklorists and storytellers as Seamus MacManus, Francis McPolin, Joseph Campbell, Henry Glassie, Patrick Kennedy, William Butler Yeats, Sinead De Valera, Eileen O’Faolain, Ruth Sawyer, Michael J. Murphy, Sean O’Sullivan, William Carleton, Katherine Briggs and Eddie Lenihan (to name only a very few) have been like butterfly collectors searching for stories of Ireland’s mystical people, the ‘Sidhe’. Only they set them free again for others to go and find them for themselves.

As the storyteller Eddie Lenihan told me when I asked him about collecting stories:

These stories are not yours or mine, they belong to the people who were kind enough to tell them to me while they were still able to. I in turn regard it as my duty to share them with others. Through this process, hopefully, the stories will live on.

These enigmatic creatures go under many names, such as the good folk, the wee folk, the gentle people, the fey and even the other crowd. The term ‘fairies’ is merely an Anglicisation for something that cannot be defined or pigeon-holed, just like the Sidhe themselves.

But the fairies of Ireland are not the magical or elaborate fairies that we know from stories such as Cinderella or Peter Pan, or the paintings created by the Victorian and Edwardian artists Richard Dadd and Edward Robert Hughes, or the photographs of the Cottingley Fairies fabricated by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths during the reign of King George V (1910–1936), nor are they the delicate sweet fairies we see in a Disney film.

The Sidhe lend themselves more to the imaginings of Edgar Allan Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, Harry Clarke, Sheridan Le Fanu and Bram Stoker, hence the title of the book Irish Gothic. In fact, Bram Stoker, an Irish man born in Clontarf, Co. Dublin, in 1847, listened to many strange and disturbing stories about the Great Famine of Ireland (1845–1849) and the good folk from his dear mother. It was such stories that helped create the literary landscape for Stoker’s 1897 masterpiece Dracula. Bram Stoker (1847-1912) the author of Dracula (1897) was a sickly child and spent most of his time in bedbound. During this period he would listen his mother Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley (1818–1901) tell him terrifying folk tales such as ‘Abhartach the Irish Vampire’ and ‘An Fear Gorta’ (‘The man of Famine’). She was raised in County Sligo in the West of Ireland, which was the worst place affected by the Great Famine (1845-1849). Ironically Stoker was born in 1847, which was more commonly known as ‘Black 47’ this was considered to have been the most brutal year of the famine. She would tell her young son tales of the Walking Dead, Coffin Ships and the ‘Bad Blood’ between the starving Irish peasantry and their cruel wealthy landlords. The Irish for bad blood is ‘Droch Fhola’, which is pronounced as ‘Drocula’.

In fact, it was believed by some that the Famine was indeed caused by the Sidhe. According to folklore historian Simon Young:

There was the belief among some Irish potato growers that it was the fairies’ disfavour that brought down the blight on the land. Fairy battles in the sky – fairy tribes both fought and played hurling matches against each other – were interpreted as marking the onset of the famine: a victorious fairy army would curse the potatoes of the enemy’s territory.

In Eamon Kelly’s beautiful fairy story ‘The Golden Ball’ there is a brief description of one of these fairy hurling matches.

I grew up listening to my grandmother, from Co. Galway in the West of Ireland, tell me stories about the ‘good folk’, and she was also a huge fan of the Hammer Horror Franchise. This fascination with the sublime and the strange stayed with me throughout my life in the literature, film, visual arts and even music that I loved. As a teenager I was fascinated with the gothic rock sub-culture of the late 1970s and early ’80s with bands such as Bauhaus, whose lead singer Peter Murphy, of Irish descent penned a song dedicated to the Sidhe, based on old Irish folklore, entitled ‘Hollow Hills’. In 2021 as part of my Masters, I had the great pleasure of working with David J., the bass player from Bauhaus. The Dublin based group, Virgin Prunes were an androgynous, bizarre and otherworldly ensemble headed by Guggi and Gavin Friday, who embodied the mystery, beauty, playfulness and horror of the Sidhe. The original Sisters of Mercy (1980-1985) utilised a Celtic-guitar sound in tracks such as ‘Floorshow’ and ‘First and Last and Always’, capturing the wild and feverish sound of the Sidhe. Their enigmatic lead singer Andrew Eldritch encapsulated the mysterious and menacing look of Irish folk characters such as The Joey Man (King of the Fairies) and An Fear Gorta (The Man of Famine) and then there was Siouxsie, who literally incorporated the Sidhe into her own realm with ‘The Banshees’.

These artists, along with many others from the genre, were the soundtrack to my life at a time when I was living in a very remote and rural part of Co. Kildare, surrounded by ancient castles, forts and folklore. Their music still resonates with me today.

I have written three books already on folklore: Down Folk Tales (2013), Kildare Folk Tales (2014) and Monaghan Folk Tales (2017). Eight of my stories are part of an exclusive collection of Folklore entitled The Anthology of Irish Folk Tales (2020). The research for these books gave me a great insight into folklore, folk tradition and, of course, the Sidhe. This is my first collaboration and I felt Paula was a good choice for she helped me research Monaghan Folk Tales and she comes from a magical place and is a true believer in the fairy folk.

It was through storytelling that I and Paula first met; she has always had a keen interest in what lies beyond the ethereal wall that separates our world from theirs. Since Paula was a young child living beside the mountains she would sit and wait for the fairies to come and keep her company.

Her brothers were older than her and, as she lived in an isolated area, there were no kids her own age to play with. As a result, her imagination was her playground. Paula had a powerful imagination from a young age and this helped her song writing in later years. She would sit in her garden wishing and hoping the fairies would come and visit her. Although she has never seen one, she felt a powerful connection and belief towards them. As she grew older her connection to the fairies did not fade and this caused many people to think she was herself ‘away with the fairies’!

But she remained true to her belief and remained very much an individual. It quickly became apparent as she got older that not many share her belief in fairies, yet when she asked those people if they would cut down a fairy tree they would always reply, ‘No way!’

Paula’s love of storytelling did not come out of nowhere for her cousin was the late great John Campbell (1933–2006), one of Ireland’s most celebrated storytellers. His son John Campbell Jnr was for a time Headmaster at Forkhill Primary School, where Paula was a pupil. She still has many happy memories of being taught by Mr Campbell, whom she states was one of the best teachers she ever had.

When Paula and I met, we shared our belief in the Sidhe and this is a bond we feel is sometimes more powerful than ourselves. Writing this book has been a wonderful experience but has also had many drawbacks, for we feel the fairies interfered with our plans on several occasions and did not make this journey easy for us, both as story collectors or as a couple – testing our faith in both them and each other.

During the writing of this book huge obstacles were put in our way to see if we would falter or give up. Initially we found it difficult to get people to share their experiences with us. We found this both interesting and disturbing, as many individuals today still talk of the Sidhe in hushed tones, for fear of being heard and quite possibly punished. It is for this reason that the Sidhe are often referred to as the ‘Good People’ or the ‘gentle people’, so that they will not take offence or umbrage if they hear mortals speaking of them. Some folk did not want to speak of them at all and it proved quite difficult to gather stories from each county.

At two crucial stages in this process we lost all our work due to computer problems, we managed to recover most of it but some of the material had to be rewritten and re-documented. In the early stages all of Paula’s research was wiped from her iPad. The camera that I used to document my illustrations for the book completely packed in and a new one had to be purchased.

Paula had lots of sleepless nights and bad dreams while writing this book, and a few times questioned if we should keep going. She felt for a time that maybe the fairies were telling us not to write the book, and that we were involving ourselves in something that we really do not understand.

I had read and heard of accounts of individuals being sabotaged by the fairies whilst trying to get close to them, and I was beginning to think it was a bad idea myself. However, after consulting some people who are lucky enough to have met them, they assured us that the ‘fairy folk’ would want us to write this book so the people of Ireland know about them. It’s natural and important to fear them, but it’s much more important to respect them. It is also true that anything worthwhile is never easy.

These are only a few examples of the struggles we faced while writing this book. We believe the fairies were testing our belief to see if we were serious, and maybe to see our motives for writing a book about them. We did not give up despite everything that was put in our way; we still believe in the fairies and each other – maybe even more than ever. Our belief in them and each other has become stronger as a result of writing this book.

It has been a labour of love and part of the process in creating this book has been the artwork. It has indeed been exciting, trying to imagine the Sidhe and their world visually. My old Art College friend James Patrick Ryan has been a wonderful support throughout this project. His contribution has been instrumental in the layout of the artwork. He created a set of wonderful coats of arms, one for each county, and a series of ornate borders that pay tribute to the plates of the great master of fairy illustration, Arthur Rackham (1867–1939).

James, a native of Co. Limerick, provided us with a chilling fairy story told to him by his grandmother. This story provides the chapter for Co. Limerick and is complemented by his own illustration. He also created a beautiful and intricate illustration featuring all the characters featured in the book.

The one question that I always ask while interviewing folk about the Sidhe is, ‘What do they look like?’

Some people have told me the fairies are just ‘wee folk’, who seldom grow more than 3 feet tall, but resemble ordinary human beings in every other way. Their clothing is old-fashioned and their features plain, rather more ugly than handsome. Others have said that they look just like us and one could be standing beside you and you wouldn’t know it, but there is a strange look in their eyes that gives them away. Some have said that they are beautiful beyond belief and when you see them your life will never be the same. I have heard tell of them being terrible monsters and creatures from your wildest nightmares. Many believe that the fairies are fallen angels that had nowhere to go, for they could neither enter Heaven nor Hell, and some say we can’t see them at all.

I have spoken with many people, old and young, who have experienced first-hand the mischievous ways of the fairy folk. Some have been trapped in fields for hours and days and some have been tormented after cutting a bush or a tree, but what I have found is that most people, whether they believe in fairies or not, both respect and fear them in equal measure and don’t tempt fate by interfering with what they feel is fairy property.

According to Co. Down folklorist Francis McPolin (1897–1974), most of them lived in underground caves, having secret entrances into the fairy forts, which can still be seen in varying states of ruin and preservation on most of the hillsides in the surrounding countryside. It’s believed that there was a definite hierarchy or aristocracy among the fairies and these nobles lived in underground palaces that could only be entered via the larger forts that stood upon the higher hilltops.

The general consensus is that the fairy world is composed of the original fairy people known as the Tuatha Dé Danann, or ‘The People of the Goddess Danu’. According to the Armagh folklorist Michael J. Murphy, these were an early Irish race who were skilled in magic and they were able to escape the physical death of mortal man. They were, however, compelled to dwell in fairy forts or rassans. They entertained themselves by showing off their superiority over ordinary people by playing tricks on them. This tended to take place at certain times of the year such as the 1st of May; probably the best known is the 31st of October, Halloween, when the ethereal wall between the human world and the fairy world is at its thinnest.

On these dates humans were carried off or abducted by the fairies and kept in fairyland permanently; these humans are known as ‘changelings’. To protect themselves from such abductions, Murphy stated that the old people would place iron tongs across a cradle. Apparently, fairy folk cannot perform any magic when confronted with either iron, steel or the Bible.

In fact, all the knowledge we have today about the Sidhe has been passed down by storytellers going back centuries when the written word and literacy was only a pleasure of the privileged classes and stories existed through the oral tradition.

As a storyteller myself, I have had the privilege and a pleasure to work with other storytellers and hear their tales of the Sidhe. It has been particularly fascinating to hear first-hand accounts of experiences that people have had with them. Paula and I have spoken to folklorists, musicians, priests, academics, artists, poets, farmers, fishermen, mountain folk, storytellers and characters from every background imaginable with regards to this book. Our conversations have been both enlightening and enriching and have brought so much to this book.

As this is the new edition of Irish Gothic, we are delighted to say that our book has proved to be very successful and that we have achieved our goal in collecting the most interesting and engaging fairy stories from each county.

Steve Lally

June 2022

‘FIRESIDE TALE’

by Steve LallyIn memory of ‘Granny in Galway’, Margaret Power King

Well folks come gather round

And listen to a tale

From a long time ago

I heard it from my Grandmother

It must be forty years or so

Well she sat me on her knee

Beside the fire, burning bright

And when my Granny told a tale

You would listen to her carefully

Deep into the night.

She looked me in the eye

All her wisdom shining through

And I knew…

She was going to tell me

A thing or two

About a thing or two.

‘Now what time do you think it is?’

Her voice all hushed and low

‘Well, tell me now…

Don’t you know?’

Of course, I did not know at all

But the shadows dancing on wall

Told me it was very late

For the only light there was

Came from the fire

Flickering in the grate

‘It’s midnight,’ she said to me

‘It’s the witching hour, oh yes!

And who comes out at this time?

Go on now, take a guess!’

Well I racked my brains

And I thought real hard

And then it came into my head

‘Mam and Dad, they stay out late

And they’d be angry if they knew I was not in bed.’

‘No, they go out, but these come out

Two very different things,

Some have fangs and fly with wings

Others howl and growl and bark

And their eyes, they light up in the dark!’

‘But the worst of all are very small

And play tricks on little boys

When they don’t eat their dinner

Or put away their toys!’

‘Who are they?’ I had to say

My voice was just a choke

‘Oh! They are the Fey

The Sidhe

Better known as…

The Fairy Folk!’

Well I looked at her

And she looked at me

As I sat that night upon her knee

She told me of the the Fairy Tree,

The Pooka Horse,

And the Banshee, of course!

Now as the fire grew dim

As the shadows danced upon the floor

Suddenly! We were startled

A sound! A rustling at the door…

‘Oh no!’ I screamed ‘It’s them I bet!

Coming to see what they can get

We better run we better hide

It’s the Fairy Folk,’ I cried

Then the sitting room door, opened with a creak

My heart was pounding, my knees were weak

The cry of the Banshee rang through my head

That’s it we’re done, we’re dead!

And the howling figure before me said…

‘Ah! Mammy, why is that child not in bed!’

1

THE PROVINCE OF ULSTER

Co. Antrim: From the Irish Aontroim, meaning ‘Lone Ridge’. Antrim is a county renowned for its natural beauty and mythology. One of the world’s most famous landmarks can be found along the coast of Antrim, the Giant’s Causeway, built by the legendary hero and giant Fionn mac Cumhaill. The famous hexagonal stones are known as Clochan na bhFomharach, which means ‘Stones of the Formorians’. The Formorians were an ancient demonic race that were defeated by the Tuatha Dé Danann. Also in Portballintrae in Co. Antrim you will find the Lissanduff Circles, which are originally thought to be fairy forts. Part of an ancient road was found near the upper circles and it is believed that it once went south from Lissanduff all the way to Tara. Ella Young (1867–1956), the poet and Celtic mythologist and member of The Gaelic & Celtic Revival, was born in Fenagh, Co. Anrtim. Ethna Carbery (born Anna Johnston) (1864–1902) was a great folklorist and songwriter born in Kirkinriola, Ballymena, Co. Antrim.

THE FAIRY TREE (CO. ANTRIM)

Co. Antrim is indeed a fine place to find wonderful stories – from the Giant’s Causeway to Deirdre of the Sorrows. Indeed, what better place in this magical county to find stories of the good folk other than the Glens of Antrim. There are nine glens altogether and they all have many stories to tell.

According to Michael Sheane in his book The Glens of Antrim: Their Folklore and History, the nineteenth-century poet Harry Browne collected many stories of the good folk from around the Glens of Antrim for The Ulster Journal of Archeology. We too have collected some of these stories and would like to tell them to you now…

Many years ago, a young man from Glenarm told Browne about his grandfather, who had seen the good folk many times. In fact, on one occasion his grandfather had seen a fight take place between the wee folk. They were certainly aggressive wee craythurs when they got going. The old man told his grandson that he had met a fella from Cushendall with his head facing the wrong way around; ‘Be jeepers, what a sight it was!’ When he asked him what had happened, the poor chap told him that he had cut down a fairy tree. He had thought nothing of it despite all the warnings, and he went to bed as usual that night. But when he woke up he was shocked to find that his face was at the back of his neck!

Another person told of an experience he had whilst he was living in Glendun. He had wanted to cut down a Skeogh or fairy tree that was on his farmland. Well now this fella went like the Hammers a’ Hell at this lone bush with his axe and after a couple of strikes, didn’t the blade bend or turn (as they say in Co. Antrim) and he had to get another one. So when he came back with his nice new sharp axe he let out a big strike at the tree. As soon as the blade hit the trunk of the tree, blood started pouring from it. Now the poor fella got an awful shock from all this and he decided to give up on the job. He went home and went to bed, and when he woke up the next morning, sure there was not a hair upon his head, and he was as bald as an egg. After that the poor man had to wear a wig and his hair never grew back.

Now you don’t always have to cut down a fairy tree for the wee folk to get upset; in fact, if you try and build or dig near one, this can cause problems too, as you are more than likely on a fairy path. Browne talks about a chap whose son wanted to build a rabbit hutch for his pets. So he started to dig near where there stood a Skeogh, then out of nowhere he could hear a voice calling to him ‘Don’t dig here!’, but he just thought it was the wind and he paid no heed and kept on digging away. Again, the voice cried out, only louder this time, ‘Don’t dig here!’, now this time he figured it was one of his friends trying to play a trick on him, so he stopped and went to find the culprit. But lo and behold there was no one there at all and the young fellow went on about his digging, only this time the voice screamed out ‘Don’t dig here!’ and he felt something fly past him, which sent him head over heels on the grass. When he looked up he saw a strange ghostly figure that looked like a pile of rags blowing in the wind standing over him. It had no face but had eyes of burning red. It pointed a ragged finger at him and screamed once more ‘Don’t dig here!’ Well with that the young chap jumped up from the ground and took to his heels. After that he made sure to build his rabbit hutch in a far safer place away from any fairy trees.

In Emyr Estyn Evans’ classic book Irish Folk Ways he states that, ‘A fairy thorn (fairy tree), as one not planted by man, but which grew on its own, typically on some ancient cairn or rath’. It is true that the fairy tree is not grown by man; in fact it is the birds and the fauna that plants the seeds. When they eat the haws or berries of the hawthorn or whitethorn tree, they then pass the seeds in their droppings all over the countryside and that is why we see so many fairy trees all over the rural and wilder parts of Ireland.

But that is not to say that they are not sacred and possess great power – in fact, it only adds to their mystique and their total freedom from the constraints of man and modern agriculture. The poet Harry Browne states in Michael Sheane’s book that he remembered a fairy tree in Glens of Antrim, growing inside a hedge by the roadside. It stood there for a very long time and no one ever tried to clip it or prune it, for fear of a retaliation from the good folk. But after a while the tree was becoming a problem as it started to hang out over the road and it was declared that it could cause an accident or just block the road completely. So, with that a decision was made to have the tree cut down altogether. The road-man who was asked to take care of it refused point blank and would not have anything to do with such desecration. Well the old road-man eventually died and a younger fella took his place. He had no belief in such superstitious nonsense, so he went ahead and cut down the tree. Not long after this the road-man’s daughter died. It was said that some of the local people took the branches of the tree and put them under the road-man’s haystacks and it was this that had put the piseog (curse) upon him.

The fairy tree is part of a greater family of plants that grow in the wild and are associated with the supernatural. For example, foxgloves are a very common flower in the Glens of Antrim; they are sometimes called fairy thimbles or fairy hats because of their unique conical shape. The ash tree or ash plant is said to have great powers and was used by Druids in the ancient world as part of their rituals. Ash rods are placed in the ground overnight before building a house. If they are moved or damaged at all the house must be built elsewhere, as this is a sign of obstructing a fairy path.

There are many plants and herbs that grow in the wild that were used by wise men and women, or fairy doctors. These people were both feared and revered by the country folk. Two very famous fairy doctors were Moll Anthony, the Wise Woman of Kildare, and Biddy Early, the Wise Woman of Clare. These women were also known as witches or Cailleaghs but eventually they were simply called hags, which seemed to lessen their power and influence on the country folk. The hawthorn or fairy thorn is also known as the hag thorn; its berries are said to be associated with sacrificial drops of blood.

It is believed that the fairy tree is the watchtower to the Tuatha Dé Danann. These were a powerful race of magical people who ruled Ireland long before humans arrived. When the humans did arrive in the form of the Gaels or the Celts they were defeated by these mortal intruders. So they made a pact that the Gaels would live above the ground and they would dwell below. They used the whitethorn tree to look out across the land, to make sure it was clear to go on their nightly excursions and dances.