Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

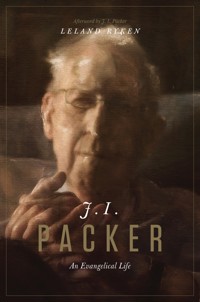

For the last 60 years, J. I. Packer has exerted a steady and remarkable influence on evangelical theology and practice. His many books, articles, and lectures have shaped entire generations of Christians, helping elevate their view of God and enliven their love for God. In this new biography, well-known scholar Leland Ryken provides readers with a compelling overview of Packer's interesting life and influential legacy. Exploring his childhood, college days, theological education, and professional life in both England and America, this volume combines detailed facts with personal anecdotes so as to paint a holistic portrait of the man himself. Finally, Ryken identifies lifelong themes evident in Packer's life, ministry, and writings that shed light on his enduring significance for Christians today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 759

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

J. I. Packer

An Evangelical Life

Leland Ryken

J. I. Packer: An Evangelical Life

Copyright © 2015 by Leland Ryken

Published by Crossway1300 Crescent StreetWheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law.

Cover image & design: Josh Dennis

First printing 2015

Printed in the United States of America

Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture references marked NIV are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

All emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the author.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-4335-4252-7 ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-4255-8 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-4253-4 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-4254-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ryken, Leland.

J. I. Packer : an evangelical life / Leland Ryken.

1 online resource.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4335-4253-4 (pdf) – ISBN 978-1-4335-4254-1 (mobi) – ISBN 978-1-4335-4255-8 (epub) – ISBN 978-1-4335-4252-7 (hc)

1. Packer, J. I. (James Innell) 2. Church of England—Biography. 3. Evangelists—Biography. I. Title.

BX5199.P22

283.092—dc23 [B] 2015018483

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

For Crossway editors, past and present

Contents

Cover PageTitle PageCopyrightDedicationList of PhotographsIntroductionPART 1: THE LIFEEarly Life and College (1926–1948) 1 Childhood and Teen Years (1926–1944) 2 The College Years (1944–1948)Theological Education and Ministry (1948–1954) 3 The Post-College Year (1948–1949) 4 Graduate Student in Oxford (1949–1952) 5 Ministry (1952–1954) 6 Courtship and Marriage (1952–1954)Professional Life in England (1955–1979) 7 Tyndale Hall, Bristol (1955–1961) 8 Latimer House, Oxford (1961–1970) 9 Return to the Academic Life (1970–1972)10 Trinity College, Bristol (1972–1979)Professional Life in North America (1979 to the Present)11 From England to Canada (1978–1979)12 Regent College (1979 to the Present)13 Christianity Today (1958 to the Present)PART 2: THE MAN14 A Portrait of the Man15 The Little-Known Packer16 What Packer’s Style and Rhetoric Tell Us about HimPART 3: LIFELONG THEMES17 The Bible18 The Puritans19 Writing20 Anglicanism21 Theology22 Preaching and the Minister’s Calling23 ControversyAfterword: J. I. Packer Reflects on His LifeSourcesIndexList of Photographs

An Oliver typewriter, such as J. I. Packer received for his eleventh birthday

Corpus Christi College, Oxford University

St. Aldate’s Anglican Church, Oxford, England, in the 1940s

Oak Hill Theological College, London

Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, England

J. I. Packer, around the time of his first teaching post, at Tyndale Hall, Bristol, England

J. I. Packer, during his tenure as warden of Latimer House

Westminster Chapel, London

Tyndale House, Cambridge, England

Regent College, Vancouver, British Columbia

J. I. Packer, speaking at Clare College, Cambridge University, in July 2010

J. I. Packer and his wife, Kit, with Lane and Ebeth Dennis of Crossway

Introduction

I became acquainted with J. I. Packer as a college sophomore in 1962, when I was browsing in a Christian bookstore in my hometown of Pella, Iowa. For reasons known only to God, I was led to purchase a paperback entitled “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God. I am the more amazed that I found the book, because it was a thin paperback that could have easily been lost on the shelf. This became one of the most influential books in my life, with my original underlining indicating what made it such a landmark for me.

In the years that followed, my reading of Packer was sufficiently thorough that as I was completing my book Worldly Saints: The Puritans as They Really Were, it occurred to me to ask Packer to write a foreword. Although we had never met in person, I had the audacity to write him and make the request. It is a tribute to Packer’s generosity that he agreed to write it, even though my stature as an author was modest. Furthermore, Packer did not write a perfunctory foreword, but a full-fledged essay entitled “Why We Need the Puritans” (which I was happy to see reappear in some of Packer’s own subsequent publications).

I met Packer in person as I was waiting for the promised foreword to appear. On that occasion, I served as Packer’s driver between a local motel and the campus of Wheaton College, where he delivered an address on the Puritans as part of an academic conference. His first words to me after we had exchanged greetings was the assurance that I “was next on [his] list,” meaning that he was ready to write the foreword. Packer was comically overprepared for his address on the Puritans, running out of time (apparently to his genuine surprise) after finishing his introduction. He then summarized his main points in the inimitable impromptu Packer manner.

I next spent time with Packer approximately fifteen years later, when we both served on the translation committee for the English Standard Version. During the next five years, Packer was a constant presence in my life, both in person when the committee met and by his comments in translation proceedings conducted in print.

What Kind of Biography Is This?

My goal in writing this biography was to enable my readers to know J. I. Packer and to get a picture of his varied roles and accomplishments. It is the man that I wanted my readers to encounter. I therefore rejected the model of the documentary history, which so overwhelms readers with factual data about events and people that the subject of the biography disappears from sight. I have not written a history, but a biography.

Because my goal was to present Packer the man, it quickly became evident that a strictly chronological arrangement of the data was insufficient as a format for the biography. A biography does, indeed, involve a life, so in the first part of this book, I unfold the story of Packer’s life. But many aspects of Packer the man span whole eras in his life. Trying to fit them into a strict chronological framework would obscure them.

For purposes of illustration, I offer the following examples. J. I. Packer is a latter-day Puritan. It is important to chronicle the beginning of Packer’s passion for the Puritans and to locate its origin in his life story. But once Packer had embraced the Puritans, they were a continuous presence in his life, and my consideration of his admiration for them could not be divided into segments that corresponded to changes in his external life. Similarly, a published history of the Tyndale Fellowship for Biblical and Theological Research in England shows that Packer was a continuous participant in the work of that fellowship for three decades. But it would have been completely artificial to attempt to match Packer’s involvement with the Tyndale Fellowship to the succession of academic positions he held during those three decades. I would note in passing that biographers who attempt to fit the life themes of their subjects into a chronological flow keep stopping the flow to digress on the themes.

The only plausible organizing framework that would allow my readers to know J. I. Packer the man was a combination of chronological biography and thematic biography, and I have accordingly followed that paradigm, with an interspersed unit that paints a portrait of the man.

Every biography is an interpretation of a person, as well as a collection of information about the person. However, this biography is light on the interpretive and evaluative side. My goal was to present J. I. Packer and leave my readers to engage in as much or as little assessment as they wished. I have made no evaluations of whether Packer did the right or wrong thing in regard to his beliefs and actions. Much has been written in particular about Packer’s loyalty to the Church of England when others separated from it and about his involvement in the movement known as Evangelicals and Catholics Together. Much has also been said about Packer’s withdrawal from Canada’s Anglican Church when others stayed within it. I had no interest in making evaluations of Packer’s stand on the issues that drove these events. It strikes me that to attempt to do so would have been out of place in a biography, and a violation of the Puritan principle that a person is bound by his conscience before God.

Signposts for What Is to Follow

Many biographies end with a chapter of “conclusions,” in which the author casts a retrospective glance over the material that has preceded and extracts some leading themes from the data. I chose to begin with a series of signposts so my readers can look for evidence of them as they read this biography. The following are themes that emerged as I lived with the material and that I want my readers to look for in my account.

1. Paradoxes. Right at the start of my research for this biography, I was handed a very useful piece of theory regarding biographical writing. It is the idea that people are paradoxical and mysterious creatures. Identifying the paradoxes is a useful framework for understanding the subject of a biography, even if the apparent contradictions remain mysterious. J. I. Packer’s life embraces a more-than-ordinary number of paradoxes, including the following:

Packer is theologically and temperamentally a Puritan, and in his college days, he was influenced by the Plymouth Brethren strain in British evangelicalism; yet he remained devoted to the Anglican Church throughout his life, and he has affiliated with movements sympathetic to Roman Catholicism.Packer is quintessentially British, yet he has lived nearly half of his adult life in Canada, and (to extend the paradox even further) his sphere of greatest influence is the United States.Packer is one of the most famous modern evangelicals, yet he has never held high-visibility positions such as prestigious pulpits or professorships at large universities.Packer is by nature a peacemaker and a gentle man, yet he has had a career of controversy in the sense that much of his writing has been polemical and his stand on religious issues has often made him the object of criticism.Throughout his life, Packer refused to bolt from the Anglican Church when pressed to do so, yet he ended up withdrawing and in effect being expelled from the Anglican Church of Canada.Packer loves specialized scholarship, yet most of his writing has been oriented to the general Christian public and ranks as “mid-level” work.Paradox is thus one of the underlying themes that I want my readers to note as this book unfolds.

2. Selfless Service. Another unifying theme in Packer’s life is his overriding sense of calling to serve the church—both the church as an institution and as the worldwide community of Christians. At every turn, Packer has primarily accepted tasks and positions that have been helpful to Christians in their walk with God, with no concern for professional advancement. Packer is utterly devoid of concern about professional advancement. A look at the nature of his publications (both books and articles) is one way to see this. But Packer’s speaking career likewise shows his propensity to say yes to virtually every invitation that has come his way. Those who have seen this willingness to agree to speaking and interview invitations marvel that Packer has been such a prolific writer in spite of the inroads on his time that he has allowed.

3. Quiet Service. Despite his high visibility among evangelical Christians, much of Packer’s investment of time and ability has been behind the scenes. I was alerted to this right at the outset of my writing of this book, and I have seen it at every turn. One cannot even imagine how many meetings of Church of England committees Packer attended during his years as a semi-official evangelical representative on such panels. For several decades, Packer has not only served as an advisor toChristianity Today, but has also critiqued every issue of the magazine, including its advertising and graphics. In fact, he has continued these critiques to the present day, even after the magazine’s finances made it a voluntary activity. Again, Packer is on record as saying that his work on the translation of the English Standard Version of the Bible is his greatest scholarly achievement, but all that the public at large sees of this is the notation that Packer was the general editor of the translation.

4. Varied Roles. Another theme that emerges in this biography is the many-sided nature of Packer’s life and achievements. The range of roles that he has filled is breathtaking. Along with this trait is his transcendence of labels. The most customary category into which I see Packer placed is that of theologian, but other categories seem equally natural to me based on my acquaintance with him: church historian (Puritan scholar), classicist, writer on topics of Christian living (implying a scope that the label theologian does not quite capture), academician, consultant, Bible translator, churchman, and editor.

Packer’s career has been a case study of entering the open doors that God and people have placed before him. This is obvious in the academic positions that he has held (particularly in England before he moved to Canada), the books and essays he has published, and the speaking engagements he has discharged. Relatively few of the items that appear in Packer’s vita were part of a planned program or professional path. Instead, Packer has trusted to providence in accepting invitations that were placed before him, governed by the impulse to minister to God’s people. I note therefore the aptness of the title of a festschrift that was composed in Packer’s honor: Doing Theology for the People of God. Packer did not enter theology for the sake of “making a scholarly contribution,” as the academy tends to conceive of a scholarly career, but “for the people of God.”

5. Setbacks and Successes. A final theme that I will flag here at the outset is the degree to which Packer has risen above calamity and disappointment to achieve greatness. One thinks most immediately of his life-changing physical injury at age seven. Packer has not held the high-visibility professional positions that most scholars of his ability enjoy, and there were setbacks in his academic career in England for which he was not responsible. Yet the world became Packer’s classroom through his writing, and the Christian world has been immeasurably enriched by his speaking in modest venues as well as prestigious ones.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the following people and to acknowledge the published sources to which I am particularly indebted. Lane Dennis, president of Crossway Books, is the “only begetter” of this biography in the sense that he asked me to write it. In turn, neither Lane nor I would have felt free to pursue the venture without the approval and help of Packer himself. In addition to the telephone interviews with Packer that I list as sources for the early chapters, every chapter in this biography bears the imprint of two days of conversation that I had with him at the Crossway offices on June 16–17, 2014. Although I have not noted this source of information in my summaries at the end of the book, I drew heavily on these conversations, which I count among the greatest privileges of my life. I also could not have written this biography without the pioneering and monumental work of Alister McGrath in his masterful book J. I. Packer: A Biography (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1997). Here, too, I would not have felt free to write my biography without the blessing of McGrath, whose permission was immediately and warmly extended to me. In the acknowledgments in his book, McGrath notes that just under three hundred people (half of whom he names) gave him access to data. This primary research was invaluable to me. I also owe an immense debt to a source that might seem inconsequential compared to McGrath’s book, but that was nonetheless worth its weight in gold: “Bibliography of the Works of J. I. Packer,” in J. I. Packer and the Evangelical Future: The Impact of His Life and Thought, ed. Timothy George (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2009), 187–230.

Part 1

THE LIFE

A biography is more than the story of a person’s life, but it is not less than that. The events that have made up J. I. Packer’s life to date are the starting point for understanding him and his work. We might think of them as the plotline on which the person and his activity for the kingdom of God are fleshed out.

Packer’s life is promising material for a story. He has done so many different things that his life sometimes reads like an adventure story. As with any adventure story, there have been striking and abrupt shifts in location. The stakes have sometimes been very high. And there have been ups and downs.

But this adventure story is a narrative of divine providence, reminiscent of the story of Joseph in the book of Genesis and perhaps of Hamlet in William Shakespeare’s masterpiece. In the most famous speech on the subject of providence in Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet expresses the sentiment that “there’s a divinity that shapes our ends.” That is the ultimate pattern in the story that makes up Part 1 of this biography.

Early Life and College

(1926–1948)

1

Childhood and Teen Years

(1926–1944)

When we consider great and famous people, it is natural to think of them as having always been great and famous. After all, that is how we know them.

The J. I. Packer that we know certainly ranks as a great and famous man. In 2005, Time magazine included Packer in a list of “The 25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America,” and entering the name J. I. Packer on an Internet search engine yields over seven hundred thousand hits. When we consider data like that, it is natural to believe that Packer has always been great and famous.

But, of course, this is untrue. Great and famous people are not born so, but as ordinary specimens of humanity. James Innell Packer was no exception.

Early Years

Packer was born on July 22, 1926, in the village of Twyning, near the city of Gloucester. His childhood home was in the heart of Gloucester, which is located in a region of England known as the South West, not far from the border of Wales. Packer calls Gloucester a market town. It is also a cathedral city, which means that the church has a more-than-usual institutional visibility on the local scene. Cathedral cities in England perpetuate the external rituals of the Anglican faith, creating plenty of scope for nominal Christianity.

At the time of Packer’s upbringing, Gloucester was also a rail center of some importance in England, and his father, James Percy Packer, oversaw the general office of the Great Western Railway at Gloucester. By Packer’s account, his father was unsuited for major responsibility and was comfortable with the fact that his duties mainly involved dealing with such matters as lost luggage claims. The office staff consisted of only two people beyond Percy—a junior clerk and a typist. The Second World War increased the workload enormously, and at the age of fifty-two, Packer’s father suffered a temporary mental collapse leading to early retirement.

The Packers were thus a lower-middle-class family, and we can say that J. I. Packer came from humble roots. In fact, a generation or two earlier, his ancestors had farmed in Oxfordshire. Throughout his life, Packer has retained what Britons call “a West Country burr,” which one dictionary defines as a way of speaking English in which the “r” sound is more noticeable than in ordinary pronunciation.

People who know Packer can attest that he has never lost the common touch. One friend recounts that Packer commended a local restaurant to her with the statement: “This place has a homespun feel. That’s why I like it.” I recall that when the translation committee that produced the English Standard Version met in Cambridge, England, the committee members occasionally ate the noon meal in a restaurant, and Packer was faithful in making the waitress feel appreciated. Similarly, when Packer ate the evening meal in my home on the occasion of my first meeting him in Wheaton, he inquired of my wife what the main dish was called and commended her for its deliciousness.

Throughout his childhood years, Packer lived in a modest rented home. On the ground level were what former generations called a “front room” (a living room for receiving guests), a dining room, a kitchen, a pantry, and what in England is called a “scullery” (an all-purpose kitchen and laundry room). There was a piano in the front room. The upstairs consisted of three bedrooms and a bathroom. Gas lighting was replaced by electricity when Packer was six.

Packer was the firstborn child in his family, with his sister, Margaret, being born three years later. His middle name, Innell, sounds nearly aristocratic, and the initials J. I., by which Packer became known, are immediately impressive (perhaps especially to American ears). Innell is a Packer family name, and its choice as a middle name is an endearing piece of family history. An unmarried second cousin of Packer’s father bore the surname of Innell, but she was the last in a family line. Packer’s father acquiesced in her request to give his newborn a middle name that would perpetuate her family name.

Packer describes his early years as uneventful. The family’s house had fenced-in front and back lawns, where Packer engaged in normal boy’s play. His father’s employment by the Great Western Railway made steam trains a fascination to him, and one of his favorite toys was a train set. He also played with a construction kit, drew pictures, and read.

From his early years, Packer was a shy boy who did not mingle easily with his peers. When asked in his eighties what he most remembers about his childhood, he replied, “Solitariness.” While Packer was a self-described introvert, his sister was the opposite. Margaret had many friends, but Packer had “very few” (his own testimony). However, Packer claims that he has “always been able to be happy on my own.”

People who have written biographically about Packer all describe him as a loner, solitary, and isolated in his childhood. Packer himself has shared that when he first felt the call to ministry during his second year in college, he hesitated because he saw himself as “an odd person, somewhat solitary and, as I thought and felt, very poor at human relationships.” However, he has also recorded that God “overpowered me, telling me I must trust him and go ahead.”

People who have known Packer in his adult years find it hard to picture him as anything but sociable and gregarious. When the translation committee of the English Standard Version met in Cambridge, it faced a daily choice between eating a catered lunch at Tyndale House or walking to a restaurant on the Cam River. An excursion to the restaurant extended the time to a whopping two hours, but Packer was a consistent advocate of the more sociable amble and sit-down lunch.

When I noted to Packer that people who know him today find him a gregarious person, he offered two explanations for the apparent contradiction. One is that introverts “don’t enjoy being introverts” and find ways to compensate and even behave like extroverts in social situations. Second, when Packer became a Christian, the words love and fellowship became, he said, “heavyweight words” for him, and he consciously cultivated “the habit of fellowship.”

The Packer family enjoyed an annual summer holiday, and their preferred vacation was vintage British—renting a bed-and-breakfast house on the seacoast. Except for one Welsh holiday, the family regularly went to Cornwall. Packer says the family enjoyed the Cornwall coast and saw no need to vary the routine. The family traveled with “privilege tickets” that were free to employees of the train company.

When Packer’s academic ability became increasingly obvious as the years unfolded, his father was proud of his son’s accomplishments, but he did not have the background to understand them. His mother, however, grasped what was happening and continuously showed interest in what Packer was learning at school.

Packer’s maternal grandmother had been widowed in her forties and had retrained herself as a “district nurse” who visited patients. Her drive and initiative lived on in Packer’s mother, whom Packer calls “a remarkable person, clearheaded and strong-willed.” She attended a teacher training college and then had a successful teaching career at two or three schools before marrying Packer’s father. Unfortunately, she suffered from anemia during Packer’s growing-up years, an era when little help for the disease was available. She therefore led what Packer calls “a quiet life,” resting on the dining room couch between two and four o’clock every afternoon.

Packer considers his mother to be the dominant parental influence in his life. She attained what Packer believes to have been saving faith at college, but it was of an Anglo-Catholic, “high-church” nature, expressed by what the Puritans called “formalism” (performing the standard rituals of the church).

A Momentous Accident at School

In September 1933, Packer began to attend the local “junior school.” It was a difficult adjustment for the seven-year-old, who was subjected to bullying from other students. On the fateful day of September 19, a schoolmate chased Packer out of the school grounds and onto a busy street (London Road). Packer was hit by a bread van and thrown to the ground. The accident resulted in injuries that have affected Packer every subsequent day of his life.

Packer was taken to the Gloucester Royal Infirmary and rushed into surgery. The primary injury was trauma to the head. The external damage was a dent in the skull, which is a feature of Packer’s physical appearance to the present day. The formal diagnosis was what Alister McGrath (quoting the surgeon’s memorandum) calls “a depressed compound fracture of the frontal bone on the right-hand side of his forehead.” Naturally, there was fear of damage to the brain, but it proved to be much less severe than might have been expected.

Packer spent three weeks in the hospital and then six months at home for recuperation, returning to school near the end of the academic year. For three years after the accident, he spoke slowly and with a drawl, and he never regained any memory of what had happened immediately before and after the accident. Two years afterward, the boy who had chased Packer from the playground (named Arthur Oliver Cromwell!) identified himself, which Packer received as new information.

The injury had huge repercussions for Packer, but as bad as the accident was, it was a story of providence and grace as well, beginning with the sparing of Packer’s life. But the marvel goes further. The surgical procedure that was immediately performed required the extraction of fragments of bone from inside the skull to relieve pressure on the brain. The resident surgeon in the Gloucester hospital had just returned after an extended time in Vienna, where he had specialized in this very type of surgery.

Of course, the accident was traumatic for Packer’s parents, who took every possible precaution to prevent further injury to their son’s head. They curbed his physical activities in the years that followed and discouraged bicycle riding. Even more confining was a black aluminum plate, held in place by an elastic band, that Packer wore on his head from the time of the accident until the age of fifteen, when, he says, he “went on strike” and refused to wear it any longer. Packer refers to his appearance while wearing the plate as that of “a speckled bird.”

A Reader Is Born

Packer’s solitary nature intensified in the days following the accident. He felt marginalized; though he found a niche as a good learner who would help others (even those who bullied him) with their homework, he never fully participated in schoolyard games. Reading had always been more natural to Packer than sports. He recalls that he was a prodigious reader already at the age of four and always remained such, characterizing himself as “something of a bookworm.” In the wake of his accident, this appetite for reading only accelerated.

A year or so after the accident, Packer’s grandmother took him for a weeklong vacation to the coastal resort town of Torquay to help him recover from a bout of bronchitis (to which he was prone). The weather was rainy and unsuitable for walking on the beach. The boardinghouse where the pair stayed provided books for just such occasions. Deprived of his construction set and toy train, Packer began to read the books that were in his room.

He began with a collection of short stories by Agatha Christie entitled The Hound of Death. His grandmother then lent him some of her own Christie books. In his adult years, Packer became such a zealous reader of older spiritual classics that it is natural for us to think of those books as his primary reading material. But when Christianity Today conducted a poll of its contributors on the ten best religious books of the twentieth century, a nomination by J. I. Packer stood out. He chose the Lord of the Rings trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien, with a supporting comment: “A classic for children from 9 to 90. Bears constant re-reading.”

A Writer Is Born

While reading might be an expected result of an enforced convalescence, the path by which Packer became a schoolboy writer is less expected. That avenue was an ordinary typewriter.

Packer’s fascination with typewriters began when he accompanied his father to the railway office on Saturday afternoon “catch-up” trips. There were two typewriters in the office, and Packer was allowed access to one of them. At the age of eight, he taught himself to type using four fingers. The subject matter of his typing was highly unusual—copying poems such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” and Robert Southey’s “The Inchcape Rock,” although it was not the poetry but the act of typing that he found rewarding.

Packer’s passion for typing did not escape the notice of his parents, partly because it solved a problem in the making. A bicycle was the toy of choice among boys in Packer’s milieu, where receiving a bike around the age of eleven was a virtual rite of passage. But Packer’s parents were fearful of any physical activity that might further injure their son’s head.

On the morning of his eleventh birthday, Packer hastened to the living room, where the family made a practice of placing birthday presents. He had given hints that he wanted a bicycle and expected to receive one. What he found was a used typewriter that seemed to him to weigh half a ton. Yet, old as it was, it had been well serviced.

For his eleventh birthday in 1937, J. I. Packer was given a used Oliver typewriter, similar to the one pictured here.

If the birthday boy was disappointed, he did not let it show. He at once put paper into the typewriter and began to type. According to McGrath, the typewriter became “the most treasured possession of his boyhood.” Its legacy was long lasting: to this day, Packer types his books and correspondence on a typewriter instead of a computer.

The acquisition of a typewriter gave impetus to Packer’s early writing. He began to compose stories about school and space travel, two genres that youngsters of the time read in weekly publications. Packer contributed his stories to “magazines” produced by friends at school. It can be hard to pinpoint when an eventual author first contracts the “infection” of writing and publishing, but my theory is that the seeds are planted early. I have no intention of being overly dramatic when I ask what Packer’s life and career would have been like if he had received a bicycle instead of a typewriter for his eleventh birthday.

Some sixty-five years later, Packer was able to see the hand of providence in his parents’ decision not to give him a bicycle (he did receive a bicycle on his thirteenth birthday, when he was physically able to handle it). In this, Packer “came to discern that what he had experienced was outstandingly good parenting, though it had not felt like that at first.” Packer added that he “cannot forget that the head injury became a happy providence eleven years later,” excluding him from conscripted military service at the age of eighteen and enabling him to go to Oxford University, where he became a Christian, which Packer thinks “would hardly have happened to him in the army.”

In September 1937, not long after that memorable eleventh birthday, Packer made the transition from the local “junior school” to the Crypt School in Gloucester. The school was prestigious, having been founded in 1539, the approximate time when King Henry VIII broke with the Church of Rome and established the Church of England. Ironically, in view of Packer’s nominal Christianity at the time, but prophetically in view of what he became, the Crypt School counted among its former students the English preacher and evangelist George Whitefield.

At the Crypt School, Packer chose to specialize in “classics.” This involved the study of the language, literature, and history of ancient Greece and Rome. A double significance might be seen in this decision. First, when Packer went on to Oxford University, he again chose the track known as classics. Second, Packer was the only student in his class at the Crypt School to choose classics. It was an early indication of his willingness to travel less-trodden roads, a tendency that has led many to judge him to be “in a class by himself.”

The Religious Climate at Home and Church

Packer came from a churchgoing family, but the Christian commitment was nominal rather than genuine. The Packer family regularly attended a local Anglican church (St. Catharine’s), but Packer recounts that his parents did not require him to attend Sunday school, no one “talked about the things of God” at home, and there was no prayer at mealtimes. In my conversations with Packer, he said that it was considered “in bad taste to talk religion” in his home. He recalls a three-year span in his teen years when he “wondered what is real in Christianity.” His home environment did not provide adequate answers.

In nominally Christian families in the Church of England, there is a strong impetus to perform longstanding church rituals, and this was true in the Packer family. One of the benchmarks in the Anglican Church is confirmation, a rite of initiation in which children who were baptized as infants claim oneness with Christ as their own experience based on faith in the gospel. When Packer was fourteen, his mother expressed the desire that he be confirmed. In her background lay the influence of the Anglo-Catholic (high church) revival of the nineteenth century. Packer agreed to be confirmed, even though he did not possess saving faith in Christ and, as he says, “indeed did not know what it was.”

It was not an ordinary confirmation, however; Packer missed the application deadline, which meant he did not attend the regular confirmation classes offered by the vicar of the church. However, the church had a new curate, a young man named Mark Green, who offered to teach Packer in a one-on-one tutorial. The instruction followed a high-church path, so the focus was moral rather than spiritual. Talk also centered on preparation to receive Holy Communion, but nothing was said about personal conversion. Green recalls Packer as a “shy and reserved” teenager who was nonetheless “very receptive and attentive” to the instruction.

Religious Encounters at School

Although Packer did not receive what we today call a Christian education, the religious influence at school was important in his life. Significantly, it was in school that Packer first encountered the writing of C. S. Lewis.

A teacher at the Crypt School was in charge of Packer’s class during one time slot per week devoted to “general studies.” He needed a book that would stimulate discussion among his students. He chose the recently published The Screwtape Letters, thereby introducing Packer to Lewis. Lewis, who was just beginning to attract the attention of the British public, had originally published the thirty-one chapters of this book as a series of articles in a religious newspaper. The format of the book—imagined letters from one devil to another—could hardly have been more captivating to a schoolboy.

We can see in this encounter with a book authored by Lewis yet another example of divine providence. Was the teacher a Christian? Packer’s remembrance is that “it does not seem so.”

There was another religious influence at school of a more indirect nature. Packer began to play chess with the son of the local Unitarian minister. As they played, Packer’s classmate attempted to convert him to Unitarianism. The arguments struck the fifteen-year-old Packer as illogical. In Packer’s words, “Unitarianism affirms the ethic of Jesus as the most wonderful thing since ice cream and negates the divinity of Jesus as superstition.” Packer could not help wondering why, if his Unitarian friend believed part of the New Testament, he did not believe more of it. Why deny something so central as the deity of Jesus?

This way of formulating an issue became a lifelong paradigm for Packer. For example, in a 1981 essay entitled “Is Christianity Credible?” Packer asks, with regard to such modern influencers as Friedrich Schleiermacher, Albrecht Ritschl, Adolf von Harnack, and Ernst Troeltsch: “Why, if this man believes so much, does he not believe more? but if he believes so little, why does he not believe less?”

Packer’s Anglican churchgoing had given him a rudimentary understanding of the Christian faith, though without any inner conviction regarding it. The sparring with his Unitarian friend prompted Packer to start thinking seriously about what constituted religious truth. In his own words, “My mind had been grabbed by the question, What is true Christianity?”

Reading the Bible was a starting point for answering that question. Lacking a Bible of his own, Packer used his grandmother’s copy of the King James Version. He read it avidly. At the same time, Packer encountered another newly published book by Lewis entitled Mere Christianity. Later readers of this landmark book (as influential in my own life as Packer’s “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God) know that it began as a series of fifteen-minute wartime radio talks on the BBC (British Broadcasting Corp.), which subsequently were published as three short books before being combined in a single volume in 1952. Packer witnessed the birth of the book as described, reading the trilogy as the individual books were published.

What was the nature of Lewis’s influence on Packer? He has answered that question in a series of articles and interviews. One of these articles, written in 1988 on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Lewis’s death (and after Packer had been reading Lewis for forty-five years), shows that the religious impact of Packer’s early reading of Lewis was more subliminal than direct. Packer writes that he “enjoyed Screwtape Letters and Mere Christianity more for their manner than their matter, for Lewis’s writing style made him seem both a fellow schoolboy and a wise old uncle simultaneously.” After Packer’s conversion, Lewis seemed “more grandfatherly,” a change that Packer ascribes more to himself than to Lewis. A decade later, Packer attributed somewhat more significance to his encounter with the two Lewis books, saying that they “brought me, not indeed to faith in the full sense, but to mainstream Christian beliefs about God, man, and Jesus Christ, so that now I was halfway there.” According to Packer’s analysis, the long-term effect of his encounter with Lewis was that he came to see the reasonableness of the Christian faith, the moral demands of discipleship, and the reality of heaven as a home.

Planning for College

Given Packer’s lower-middle-class background, it was not a foregone conclusion what he would do when he reached college age. His headmaster at the Crypt School, David Gwynn Williams, had received his college education at Corpus Christi College, part of Oxford University, and was convinced that Packer had the ability to be accepted at Oxford. Of course, a series of factors, including finances, needed to fall into place for this to happen. (Being poor, Packer’s parents had always made it clear that advanced education would depend on his getting scholarships.)

In March 1943, Packer’s last year in what North Americans call high school, the Oxford University Gazette published details of scholarships for classics students applying to Corpus Christi College. Oxford University scholarships fell into two categories—those for students who belonged to certain named groups (such as sons of Anglican clergy) and those that placed no restrictions on applicants (“open” scholarships). Corpus Christi College advertised two open scholarships for the upcoming academic year. Both were for 100 pounds, small by today’s standards but substantial at the time. The awarding of the two scholarships would be based on a competitive examination to be administered in Oxford in September 1943.

Packer sat for the examination over a two-day span. It was his first genuine trip to Oxford (though he had once bicycled from Gloucester to Oxford and back in a single day on one of his numerous long and solitary cycling ventures, a total distance of about a hundred miles). It is in keeping with Packer’s temperament that he returned to Gloucester thinking that his performance on the exams was undistinguished. Nonetheless, he received the Hugh Oldham Scholarship, which would enable him to attend Oxford University.

Waiting for College

Even though Packer had been accepted into college, he was only seventeen, which was considered too young to begin his Oxford education. This left him with free time, though technically he was still enrolled in his “sixth form” at school. With characteristic industry, Packer made it a year of intellectual advance. The academic distinctions that Packer received at this era of his life were a tribute to his intellectual ability, but they were also signposts that he was destined to achieve great things.

To begin, the Crypt School named him head prefect. This title is part of the school system in England, where schools sometimes name a “head girl” and “head boy.” It is partly an honorific position that signals the esteem with which the school regards the recipient, though the post brings tasks as well.

Also at this time, Packer began his lifelong process of self-education. He spent the year largely in self-directed reading, and trips to the public library were a regular feature of his life. Packer’s reading program showed not only the seriousness of his intellectual quest, but also his continuing interest in religious matters. He read Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, as well as Russian novels by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (The Idiot; Crime and Punishment; The Brothers Karamazov; and The Devils, a title more often translated as The Possessed). These novels with Christian premises seemed more truthful to Packer than Freud’s attempt to explain Christianity away. Packer told me that he became “a Dostoyevsky addict,” much impressed by how the Russian novelist “takes the skin off his characters and allows us to see what they are like.”

A schoolboy friendship with Eric Taylor was also an important part of Packer’s final year at the Crypt School. While Packer spent his third year in “sixth form,” Taylor made the transition to the University of Bristol. During that year, Taylor became a Christian, and he wrote letters to Packer about his new-found faith. Packer did not fully understand the letters, especially one that contained an exposition of the final verses of Romans 3, on justification by faith. Packer also was puzzled by references to “saving faith.” During the following summer vacation, Taylor and Packer had a series of conversations about the Christian faith. The discussions left Packer feeling that something was lacking in his life, but he was mystified as to what it was. Although Taylor did not lead Packer to faith, he did the next best thing by encouraging Packer to make contact with the Oxford student group called the Christian Union.

One of the most revealing statements that Packer has made is that he went to Oxford University actually believing himself to be a Christian. The basis of that belief was that in school debates with atheists, he had found himself defending Christianity as a belief system. However, in his first year at Oxford, Packer would realize his true spiritual state and experience conversion to Christianity, after which, he has said, he was “very conscious of wasted years and was trying to catch up.”

Summary

Any Christian reading the foregoing account of J. I. Packer’s pre-college life can see it as a story scripted by God’s providence. It is nothing less than a “hound of heaven” story. Packer’s life-changing accident diverted him from dreams of being a cricket player to being a more devoted reader and a writer. He did not grow up in a believing family, but he had continuous contact with the basic doctrines of the Christian faith at home and church. He was a seeker with spiritual promptings. And he had a Christian friend who wanted him to pass from spiritual death to life. All the ingredients were in place that would lead Packer to take the step into personal faith.

2

The College Years

(1944–1948)

When J. I. Packer arrived at Oxford, he was doubly prepared to make the most of the experience. Academically, he had long been a serious student and possessed the intellectual spark. Spiritually, a foundation had been laid for the conversion that happened almost immediately after his arrival.

Oxford University as Packer Found It

Packer made the trip to Oxford in early October 1944, in the midst of the Second World War. He traveled by train, using a free ticket available to him as a family member of a Great Western Railway employee. With his suitcase in hand, he walked the mile from the train station to Corpus Christi College in central Oxford.

To catch the flavor of Packer’s college experience, we need to assemble a picture of what Oxford was like during the war. The university bore the signs of being in crisis. The war was in its late stages, but not yet over. The Oxford student body was still almost entirely male, and most of the surviving able-bodied men were in the army. Blackouts made the city dark at night, creating a sense of a place under siege. Most colleges were carrying on at a greatly reduced level, with sections of some completely shut down.

Packer was eighteen years old, and during the war, most entering students of that age enrolled in six-month courses before going into military service. Packer was one of a few eighteen-year-olds who were enrolled as full-time students, expecting to be in college for three or four years. Corpus Christi College had dwindled to an enrollment of twenty-four undergraduate students, divided equally between full-time students and short-term students from the armed forces. Not only students were away at war: so were young professors. Two of Packer’s professors had been brought out of retirement to teach the classics courses.

The main entrance and Pelican Sundial (built in 1581) of Corpus Christi College at Oxford University, where J. I. Packer studied from 1944 to 1948. (Photo © Godot13. License:http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode)

Life in the colleges was austere. Heat in the rooms was inadequate and the food poor. The heat in dorm rooms was provided by coal fireplaces, but coal was in short supply because of the war effort. The fact that the library was well heated was a mixed blessing: it encouraged study by those who were serious students, but it also attracted those in search of warmth rather than books and desks. The library was always packed, and students often had to sit on the floor.

Packer was a student in the classics track, meaning that the content of his studies was classical literature, history, and philosophy. It was a rigorous path, taking four years in contrast to the three years required for other tracks. The classics curriculum included language study, as well as reading of the great texts. One of Packer’s duties within his college was to recite from memory a long Latin prayer before formal dinners in the dining hall.

The classics curriculum at Oxford University was (and remains) systematic and fixed. The program is divided into two categories, with the second building on the first. The first category occupies five terms and the second seven terms, adding up to four academic years. With three terms per academic year, the system is equivalent to what in the United States is called a quarter system, as distinct from a semester system. The first segment is mainly the study of ancient Greek and Latin. The method of education consists primarily of weekly one-on-one “tutorials” with a master or tutor, supplemented by voluntary attendance of lectures sponsored by the university at large. In a tutorial, a student reads aloud an essay he has written, which the tutor then critiques. The second part of the program consists of reading primary texts in a wide range of subjects stemming from the Greek and Roman cultures, including ancient history and ancient and modern philosophy.

Although Packer gave priority to the Christian side of life and the activities of the Christian Union, he was not impatient with the time he spent on Greek and Latin language study and the reading of masterworks in those languages. Packer had come to enjoy the Greek and Latin languages, finding that they “have their strengths and fascination,” with the result that mastering and using them provided “a rather good feeling.” He entered Oxford with a well-developed grasp of both Greek and Latin, giving him a head start on his college studies. By his own testimony, he “had the ability to become a classical scholar,” and several professors attempted to influence him in that direction. But the bent of his being following his conversion was in the direction of Christian scholarship and ministry.

The classical author whom Packer “most admired” was the Greek dramatist Aeschylus, whom Packer regarded as a master of language, similar to William Shakespeare in English literature. In Packer’s words, “Aeschylus handled language in a forcible way, and I always admire writers who handle language in a forcible way.” Packer also enjoyed reading Homer, though not with the same passion with which he read Aeschylus. Among Latin authors, the historian Livy was Packer’s favorite on the strength of the vividness of his writing.

Only one professor touched Packer deeply. He was a displaced Jew named Eduard Fraenkel, affiliated with Packer’s own college (Corpus Christi). Fraenkel was a legendary classical scholar of his era whose name lives on today. Packer attended only one Fraenkel course, on the Latin poet Horace, but he was awed by Fraenkel’s extemporaneous lecturing as he roamed up and down the aisles of the classroom.

The classics curriculum bore fruit in Packer’s later life and career, and we can say with confidence that his Oxford education served him well. In his role as general editor of the English Standard Version of the Bible, Packer sometimes dazzled other committee members with his knowledge of Greek and the nuances of classical rhetoric. Additionally, he benefited from the Oxford model of individualized education and frequent presentation of essays, a model that is designed to produce a certain quality of mind, including precision of thought and expression, and careful organization of material. Packer’s writings display a quality possessed by another Oxford classics student, C. S. Lewis, namely, the ability to follow a line of thought to its logical conclusion, breaking the main topic into its constituent parts and making complex ideas clear to the general reading public.

In conversation with me, Packer described the Oxford method as “throwing a student into the deep end and seeing how he does.” For a classics student such as Packer, this was, he said, “the best education I could have had.” However, it is not the model Packer followed in his own teaching, since he realized that most students need help in learning the basic ways of philosophical thought.

I entitled this section “Oxford University as Packer Found It”; I want to end it by reversing that to consider J. I. Packer as Oxford University found him. Packer’s self-portrait as an entering college student reveals “a man of like passions such as we are” (see James 5:17), not the commanding figure that he became. Here are formulas that Packer later used when he cast a retrospective look at himself as an Oxford student:

“. . . an immature and churned-up young man, painfully aware of himself, battling his daily way, as adolescents do, through manifold urges and surges of discontent and frustration.”“I was an oddity. I was bad at relationships, an outsider, shy, and an intellectual.”“. . . an eighteen year-old oddball, . . . emotionally locked up.”“. . . a shy, introverted, and awkward young man.”This picture is so different from the J. I. Packer that we know that we need to accept the self-portrait as carrying the authority of the person who observed himself firsthand.

Packer’s Conversion

As noted in the preceding chapter, Packer’s school friend Eric Taylor had urged him to seek out the Christian Union (an Inter-Varsity organization) when he arrived at Oxford. It so happened that Packer did not need to do this.

Christian student groups at Oxford and Cambridge Universities were highly active in the middle of the twentieth century. The Christian Union at Oxford followed a practice of arranging social events in the respective colleges for new students at the beginning of each academic year. These were informational meetings designed to attract students to participate in the gatherings of the Christian Union of the university as a whole. Nearly everything at Oxford University is traditional, and the opening recruitment meetings of the term happened specifically on the Thursday evening before the start of the academic year. Ralph Hulme, the Corpus Christi representative for the Oxford Inter-Collegiate Christian Union, contacted Packer and invited him to the introductory Thursday meeting.

I will note in passing that as I did the research for this biography, I was pushed to the limit by the dozens of acronyms that make up the history of evangelical organizations in England during the twentieth century. On my trips to Oxford through the years, I had heard references to OICCU (too oddly pronounced to reproduce it here, though “oi-kew” comes close) and to a sister organization, CICCU (“kick-you”), at Cambridge University. In the United States, we would prosaically refer to either of these groups as “the local InterVarsity chapter”!

Packer accepted Hulme’s invitation, having already determined that he would attend. The first meeting was eminently forgettable, as evidenced by the fact that the only thing Packer remembers about the event is that it failed to spark his interest!

Despite the low wartime enrollments at the University, OICCU President David Mullins (a medical student) was determined to maintain the evangelistic thrust of the Christian Union. The weekly agenda was ambitious. On the university level, there was a Bible exposition every Saturday evening and an evangelistic sermon every Sunday evening (known as “Sunday evening sermon”). Individual colleges then sponsored weekly Bible studies and prayer meetings. Packer learned about these options at the informational meeting. The first week, he decided to attend the Saturday evening Bible exposition, but not the Sunday evening evangelistic service. He did, however, attend the evangelistic service the next Sunday, October 22, 1944, a service that would change his life eternally.

The service occurred at St. Aldate’s, an Anglican church in the center of the city. It was one of the larger Oxford churches and was noted for its student ministry. St. Aldate’s is just a “stone’s throw” from Pembroke College, where bygone Crypt School alumnus George Whitefield attended college and was converted. “Dim-out” conditions were in effect, so care was taken not to allow any light to emanate from the church building. Spiritual light, however, shone within the church.

The service began at 8:15. The preacher was an elderly Anglican parson, the Rev. Earl Langston, from the resort town of Weymouth. The first half of the forty-minute sermon consisted of biblical exposition that left Packer bored. But the second half was a personal narrative of how Langston had been converted at a boys’ camp. The key component of that conversion had been a challenge posed to the youthful Langston by a camp leader, who had asked whether he was a Christian. Langston had been jolted by this question to conclude that he was not actually saved. That, in turn, led to his coming to personal faith in Christ as Savior.

This autobiographical narrative was riveting to Packer, who had entered Oxford believing himself to be a Christian. He suddenly saw his own story in Langston’s narrative and realized that he was not a believer. It was a traumatic realization that was accompanied by an imagined picture, which Alister McGrath describes as follows: “He found a picture arising from within his mind. The picture was that of someone looking from outside through a window into a room where some people were having a party. Inside the room, people were enjoying themselves by playing games. The person outside could understand the games that they were playing. He knew the rules of the games. But he was outside; they were inside. He needed to come in.”

The interior of St. Aldate’s Anglican Church in Oxford, England, around 1940. J. I. Packer was converted at an evening service at the church on October 22, 1944. (Photo courtesy of St. Aldate’s Anglican Church)

Packer was particularly convicted by the latter awareness: “I need to come in.” So by the Spirit’s prompting, he came in. The sermon ended as most evangelistic services in the Oxford milieu (and more universally) did—with the preacher emphasizing the need for his hearers to commit themselves to Christ and the singing of the hymn “Just As I Am.” Packer states simply, “I had given my life to Christ.” He also recounts, “When I went out of the church I knew I was a Christian.” More than half a century later, Packer could attest, with regard to his conversion, that “I remember the experience as if it were yesterday.”

After sharing his conversion story, Langston added that he had afterward written to his parents to tell them what had happened. So when Packer went back to his room at Corpus Christi, he followed that example and wrote his parents about the step he had taken. In a return letter, Packer’s mother expressed that she was glad he had found what he had found.

The preceding chapter pieced together various threads of Packer’s life, and those threads all converged on the night of October 22, 1944. The foundation of belief had been laid. Packer had even defended the Christian faith on an intellectual level. What he needed was a catalyst. As is nearly always the case, the preaching of the gospel brought conviction. In keeping with the paradigm expressed in the Bible itself and Christian doctrine based on the Bible, the process of conversion began with an awareness of his lost state. Packer’s friend Eric Taylor had been unable to fully show Packer that he lacked saving faith, but he had asserted the need for Packer to attain it. Nor should we miss the crucial role played by what we familiarly call a personal testimony (in this case, the preacher’s).

Believing the Bible