35,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

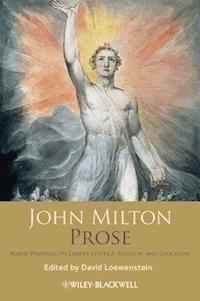

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Regarded by many as the equal of Shakespeare in poetic imagination and expression, Milton was also a prolific writer of prose, applying his potent genius to major issues of domestic, religious and political liberty. This superbly annotated new publication is the most authoritative single-volume anthology yet of Milton's major prose works.

- Uses Milton's original language, spelling and punctuation

- Freshly and extensively annotated

- Notes provide unrivalled contextual analysis as well as illuminating the wealth of Milton's allusions and references

- Will appeal to a general readership as well as to scholars across the humanities

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 2166

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Note on This Edition

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Chronology

Introduction

Milton’s Anti-Episcopal Prose and Religious Conflict

The Politics of Divorce and “Free Writing”

The Politics and Writing of 1649

Defending the English People and Himself

Milton’s Late Prose and the Crisis of the Good Old Cause

1 PROLUSIONS VI AND VII

PREFATORY NOTE

Prolusion VI: DELIVERED IN THE COLLEGE SUMMER VACATION, BUT IN THE PRESENCE OF ALMOST THE WHOLE BODY OF STUDENTS, AS IS CUSTOMARY (i) THE ORATION

Prolusion VII: DELIVERED IN THE COLLEGE CHAPEL IN DEFENCE OF LEARNING AN ORATION

2 OF REFORMATION

PREFATORY NOTE

3 THE REASON OF CHURCH-GOVERNMENT URG’D AGAINST PRELATY

PREFATORY NOTE

THE PREFACE

CHAP. I.

CHAP. II.

CHAP. III.

CHAP. IV.

CHAP. V.

CHAP. VI.

CHAP. VII.

The Second Book

4 AN APOLOGY AGAINST A PAMPHLET

PREFATORY NOTE

5 THE DOCTRINE AND DISCIPLINE OF DIVORCE

PREFATORY NOTE

1. BOOKE.

THE SECOND BOOK.

6 OF EDUCATION

PREFATORY NOTE

7 AREOPAGITICA; A SPEECH OF Mr. JOHN MILTON

PREFATORY NOTE

8 TETRACHORDON

PREFATORY NOTE

9 THE TENURE OF KINGS AND MAGISTRATES

PREFATORY NOTE

10 EIKONOKLASTES

PREFATORY NOTE

The PREFACE

11 A SECOND DEFENCE OF THE ENGLISH PEOPLE

PREFATORY NOTE

12 A TREATISE OF CIVIL POWER IN ECCLESIASTICAL CAUSES

PREFATORY NOTE

13 CONSIDERATIONS TOUCHING THE LIKELIEST MEANS TO REMOVE HIRELINGS OUT OF THE CHURCH

PREFATORY NOTE

14 THE READIE AND EASIE WAY TO ESTABLISH A FREE COMMONWEALTH

PREFATORY NOTE

15 OF TRUE RELIGION, HÆRESIE, SCHISM, AND TOLERATION

PREFATORY NOTE

16 SELECTIONS FROM MILTON’S PRIVATE LETTERS

PREFATORY NOTE

TO ALEXANDER GIL 1628

LETTER TO A FRIEND, 1633

TO CHARLES DIODATI, 1637

TO BENEDETTO BUONMATTEI THE FLORENTINE, 1638

TO CHARLES DATI, NOBLEMAN OF FLORENCE, 1647

[SINCE I HAVE BEEN FROM BOYHOOD] TO LEONARD PHILARAS, ATHENIAN

TO THE MOST DISTINGUISHED MR HENRY DE BRASS, 1657

TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS PETER HEIMBACH, COUNCILLOR TO THE ELECTOR OF BRANDENBURG

17 DE DOCTRINA CHRISTIANA

PREFATORY NOTE

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVIII

From Chapter XIX

From Chapter XX

Chapter XXVII

From Chapter XXXIII

Chapter I

Chapter VI

Chapter IX

Chapter XVII

18 THE LIFE OF MR. JOHN MILTON by Edward Phillips

Select Bibliography

Praise forJohn Milton: Prose

“This excellent selection is what I have always wanted for my students: un-modernized texts very well edited and contextualized. Milton’s seering radicalism, the extraordinary controlled freedom of his rhetoric, the engagement with the great issues of England’s revolution, but also with universal themes of God, Humankind, liberty, accountability, are made accessible as never before.”

John Morrill, Professor of British and Irish History, Cambridge University

“David Loewenstein’s scrupulous edition offers a remarkably generous range of Milton’s prose works on religion, politics, and domestic issues. The Prefatory Notes to each work are a model of clarity and concision, and annotations are precise and informative. The volume will be a wonderful resource for Milton scholars, teachers, and students alike.”

Laura Knoppers, Editor, Milton Studies

“Richly annotated and with a fine, purposeful introduction, this wholly new edition makes available ten major prose works by Milton in their entirety, together with generous selections from Milton’s other tracts. No other edition allows the reader to appreciate so fully Milton’s original engagement with concepts of political, religious, and domestic liberty. It is the best edition for teaching purposes and the general reader. Scholars too will appreciate the wealth of fresh annotations.”

Thomas N. Corns, University of Wales, Bangor

“This is the most ambitious one-volume edition of Milton’s prose to date, one that both invites the general reader who is curious about the author of Paradise Lost, and that also satisfies the needs of classrooms. Readers will have at their fingertips works from across Milton’s writing career, with its wide range of occasions and styles. We see the scrappy polemicist, the rhetorically powerful tyrannicide, the critic and participant in religious reform, a Milton who was always daring, witty and engaged. With crisp prefatory introductions to each work, helpful annotations, and a generous introduction to the whole, there is no better guide to Milton’s prose treasures than this one. I will be eager to assign this to students.”

Sharon Achinstein, University of Oxford

David Loewenstein is Helen C. White Professor of English and the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. His books include Representing Revolution in Miltonand his Contemporaries: Religion, Politics, and Polemics in Radical Puritanism (2001), which received the Milton Society of America’s James Holly Hanford Award for Distinguished Book. He is the author of Treacherous Faith: The Specter of Heresy in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (2013). He has co-edited The Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature (2002), Early Modern Nationalism and Milton’s England (2008), and The Complete Works of GerrardWinstanley (2009). He is an Honored Scholar of the Milton Society of America.

Also available:

John Milton: “Paradise Lost”

Edited by Barbara K. Lewalski

John Milton: Complete Shorter Poems

Edited by Stella P. Revard

The Life of John Milton: A Critical Biography

Barbara K. Lewalski

This edition first published 2013© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of David Loewenstein to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Milton, John, 1608–1674. [Prose works. Selections] John Milton prose : major writings on liberty, politics, religion, and education / edited by David Loewenstein. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4051-2930-5 (cloth) – ISBN 978-1-4051-2931-2 (pbk.) I. Loewenstein, David. II. Title. PR3569.L64 2013 824′.4–dc23

2012022349

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: William Blake, The Angel of Revelation (detail), c. 1805. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / The Bridgeman Art Library.Cover design by Richard Boxall Design Associates

For Barbara Lewalski and in Memory of Norman T. Burns

Figure 1 Portrait of Milton at age 62 by William Faithorne; from The History of Britain (1670). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Note on This Edition

This is an original spelling edition of Milton’s prose (except, of course, for translations of Milton’s Latin texts). It is intended for a broad readership: students, teachers, scholars, and general readers. I have prepared fresh annotations for all the texts; however, because of the need to keep this large one-volume edition from becoming too big, I have not provided annotations (except for several contemporary names) to the substantial selections from Milton’s theological treatise, De Doctrina Christiana. I have aimed to keep the annotations concise but full, so that readers of Milton’s prose can get as much as possible from the old-spelling texts. I have also followed the original punctuation.

In preparing this edition, I have followed the chosen copy-texts closely. In cases where there are clearly typographical errors in the original, I have made emendations without noting them. Biblical citations in the annotations are from the Authorized (King James) Version.

This is one of three volumes presenting the complete poetry and major prose in original language. The shorter poems are edited by Stella Revard; Paradise Lost is edited by Barbara Lewalski. Quotations from the shorter poetry are taken from John Milton: Complete Shorter Poems, edited by Stella P. Revard (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009); quotations from Paradise Lost are taken from John Milton: “Paradise Lost,” edited by Barbara K. Lewalski (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007).

Abbreviations

Any abbreviations refer to works cited in the Select Bibliography at the end of this edition. CPW refers to the Yale edition of the Complete Prose Works of John Milton, general editor Don M. Wolfe, 8 volumes (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953–82). Thomason refers to the major collection of published texts assembled by the London bookseller, George Thomason, between 1640 and 1661; the collection is kept in the British Library. Wing refers to The Short-title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and British America and of English Books Printed in Other Countries, 1641–1700 by Donald Goddard Wing, 2nd edition, revised and enlarged (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1972–98).

Acknowledgements

For help in preparing this edition, I am very grateful to a number of energetic and discerning assistants: Jon Baarsch, Claire Falck, Michael Gadaleto, Elizabeth Malson-Huddle, Vanessa Lauber, Kristiane Stapleton, and Eric Vivier. These advanced graduate students at the University of Wisconsin–Madison checked and re-checked the texts for accuracy; they also assisted me with the large number of annotations, including by noting less familiar words, names, and difficult passages they considered needed glossing. They exemplified engaged, strenuous modern readers of Milton’s prose, helping to ensure that this old-spelling edition is one that can be read and appreciated by a broad readership. I am especially grateful to Kristiane Stapleton for assisting me as I prepared the final manuscript for the press. Joshua M. Smith gave his expert advice when I had questions about Milton’s Greek and Latin. Finally, the Marjorie and Lorin Tiefenthaler Funds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison provided essential financial support during the years this edition was being prepared.

I would also like to thank warmly Emma Bennett, my editor at Wiley-Blackwell, for much helpful advice and patience as I prepared this edition. I am also grateful to Benjamin Thatcher at Wiley-Blackwell for his expertise in seeing this large book through production. I thank Fiona Screen for her expert copy-editing skills. Much work on this edition was conducted using the resources of the following libraries: the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the University of Wisconsin–Madison Library, and the Folger Shakespeare Library. I am grateful to their staffs for much assistance and many kindnesses.

I am also very grateful to the editors of the other two Wiley-Blackwell editions of Milton: Barbara K. Lewalski and Stella P. Revard. It has been a special pleasure to work with them as we discussed and designed all three volumes of Milton’s writings. Barbara Lewalski has provided much support, valuable criticism, and practical advice. Her scholarship on Milton has been exemplary in its range and depth – for its attention to the aesthetic achievements of Milton’s writing (in both his poetry and prose), as well as to the constant freshness with which Milton expresses his arguments and ideas about politics, religion, and domestic issues. This volume is dedicated to her. It is also dedicated to the memory of Norman T. Burns, with whom I was lucky enough to enjoy the kind of lively intellectual friendship Milton himself deeply treasured.

List of Illustrations

1

Portrait of Milton at age 62 by William Faithorne; from The History of Britain (1670). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

2

Eikon Basilike: The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in his Solitude and Sufferings (1649), frontispiece. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

3

John Milton, Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio (London, 1651), title page.By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Chronology

Milton’s Life

Historical and Literary Events

Dec. 9, born in Bread Street, Cheapside London, to John and Sarah Milton.

1608

1611

King James (“Authorized”) Bible.

Educated by private tutors, including the Presbyterian cleric, Thomas Young.

1614–20

Brother Christopher born.

1615

1616

Death of Shakespeare.

Portrait at age 10 painted by Cornelius Janssen.

1618

Ben Jonson’s Works published.

Begins to attend St. Paul’s School; friendship with Charles Diodati begins. (?)

1620

1621

Donne appointed Dean of St. Paul’s.

1623

Shakespeare’s First Folio published.

First known poems, paraphrases of Psalms 114 and 136.

1623–4

Admitted to Christ’s College, Cambridge (Feb. 12).

1625

Death of James I; accession of Charles I.

Outbreak of plague.

Writes funeral elegies, “In quintum Novembris,” verse epistles, and Prolusions in Latin; “On the Death of a Fair Infant,” “At a Vacation Exercise” in English.

1626–8

William Laud made Bishop of London.

Takes BA degree (March).

1629

Charles I dissolves Parliament.

Writes “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” (Dec).

Writes “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso”(?).

1631

“On Shakespeare” published in the Second Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. Admitted to MA degree (July 3). Writes Arcades, entertainment for the Countess of Derby(?). Writes sonnet “How soon hath Time” (Dec). Starts to live with his family at Hammersmith.

1632

Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems published in Italian.

Writes “On Time,” “At a Solemn Music”(?).

1633

Donne’s Poems and Herbert’s The Temple published.

Laud made Archbishop of Canterbury.

A Maske (Comus) performed at Ludlow with music by Henry Lawes (Sept. 29).

1634

Carew’s masque, Coelum Britannicum.

Moves with his family to Horton, Buckinghamshire. Begins notes on his reading in Commonplace Book.

1635

Publication of A Maske Presented at Ludlow Castle. Mother dies (April 3).Writes “Lycidas.”

1637

Trial and punishment of Puritans William Prynne, John Bastwick, and Henry Burton.

Descartes, Discourse on Method.

“Lycidas” published in collection of elegies for Edward King.

1638

Begins Continental tour (May 1638); meets Grotius, Galileo, Cardinal Barberini, Manso; visits Academies in Florence and Rome; visits Vatican Library; visits Naples, Venice, and Geneva.Writes “Mansus,” other Latin poems.

1638–9

Learns of Charles Diodati’s death.Returns to England (July).Takes lodgings in Fleet Street.Begins teaching nephews Edward and John Phillips and a few others.

1639

First Bishops’ War with Scotland.

Writes Epitaphium Damonis (epitaph for Charles Diodati). Begins work on Accidence Commenc’t Grammar, Art of Logic, Christian Doctrine(?).

1640

Long Parliament convened (Nov. 3); impeachment of Laud. George Thomason, London bookseller, begins his collection of tracts and books.

Publishes anti-episcopal tracts: Of Reformation; Of Prelatical Episcopacy; Animadversions upon the Remonstrants Defense.

1641

Impeachment and execution of Strafford (May)Root and Branch Bill abolishing bishops.Irish rebellion breaks out (Oct.).

Publishes The Reason of Church-government and An Apology [for] . . . SmectymnuusMarries Mary Powell (May?), who returns (Aug.?) to her royalist family near Oxford.Writes sonnet, “Captain or Colonel” when royalist attack on London expected.

1642

Civil War begins (Aug. 22). Royalists win Battle of Edgehill. Closing of theaters.

Publishes Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (Aug.).

1643

Westminster Assembly of Divines to reform Church.Solemn League and Covenant subscribed.Thomas Browne, Religio Medici.

Publishes second edition of Doctrine and Discipline; Of Education (June); The Judgement of Martin Bucer concerning Divorce (Aug.); Areopagitica (Nov.).

1644

Royalists defeated at Battle of Marston Moor (July 2).

Publishes Tetrachordon and Colasterion on the divorce question.Mary Powell returns. Moves to a large house in the Barbican.

1645

Execution of Laud.New Model Army wins decisive victory at Naseby (June).Edmund Waller, Poems.

Poems of Mr. John Milton published (Jan., dated 1645).Writes sonnet to Lawes.Daughter Anne born (July 29).

1646

First Civil War ends. Crashaw, Steps to the Temple.

Father dies; moves to High Holborn.

1647

Daughter Mary born (Oct. 26).Writes sonnet to Lord General Fairfax.Translates Psalms 80–88.

1648

Second Civil War.Pride’s Purge (Dec.) expels many Presbyterians from Parliament, leaving c.150 members of the House of Commons (the Rump).Herrick, Hesperides.

Publishes Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (Feb.).Appointed Secretary for ForeignTongues to the Council of State (March 15).Writing the History of Britain.Publishes Observations on Irish documents; Eikonoklastes (“The Idol Smasher”) (Oct.).Given lodgings in Scotland Yard

1649

Trial of Charles I, executed Jan. 30. Eikon Basilike (“The Royal Image”) published in many editions.Acts abolishing kingship and House of Lords (March).Salmasius, Defensio Regia. Parliament declares England a free Commonwealth (May).

Second edition of Eikonoklastes (June).

1650

Marvell, Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland. Vaughan, Silex Scintillans (Part 1).

Publishes Defensio pro populo Anglicano in reply to Salmasius (Feb. 24).Birth of son, John (March 16).Moves to Petty France, near St. James Park.

1651

Hobbes, Leviathan.

Milton totally blind.Writes sonnet, “When I consider how my light is spent”(?) and sonnets to Cromwell and Sir Henry Vane.Daughter Deborah born (May 2).Mary Powell Milton dies (May 5).Son John dies (June).

1652

Regii Sanguinis Clamor (“Cry of the Royal Blood”), answer to Milton’s Defensio, published. First Dutch War (to 1654).

Translates Psalms 1–8.

1653

Cromwell dissolves Rump Parliament (April 20). “Barebones” Parliament. Cromwell made Lord Protector (Dec), under Constitution, “Instrument of Government.”

Publishes Defensio Secunda (“A Second Defense of the English People”), answer to Regii Sanguinis (May 30).

1654

Writes sonnet, “Avenge O Lord thy Slaughter’d Saints.”Publishes Pro Se Defensio (“Defense of Himself”) (Aug.). Works on Christian Doctrine(?).

1655

Massacre of the Protestant Vaudois on order of the Prince of Savoy (April).Andrew Marvell, The First Anniversary of the Government Under O.C.

Marries Katherine Woodcock (Nov. 12).

1656

James Harrington, Oceana, published.

Daughter Katherine born (Oct. 10). Marvell appointed his assistant in Secretariat for Foreign Languages.

1657

“Humble Petition and Advice,” constitution establishing more conservative government.

Katherine Woodcock Milton dies (Feb. 3).Daughter Katherine dies (March 17). New edition of Milton’s Defensio.

1658

Death of Oliver Cromwell (Sept. 3). Richard Cromwell becomes Protector.

Publishes A Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Causes (Feb.); The Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings out of the Church (Aug.).

1659

Richard Cromwell deposed by army; Rump Parliament recalled; Rump deposed and again restored.

Publishes The Readie and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (Feb.); 2nd edition (April); Brief Notes upon a Late Sermon (April).In hiding (May); his books burned (Aug.); imprisoned (Oct.?); released (Dec.).

1660

Long Parliament restored; New Parliament called (April).Charles II restored, enters London (May).Dryden, Astraea Redux.Bunyan imprisoned (until 1672).

At work on Paradise Lost, Christian Doctrine.

1661

Regicides imprisoned, ten executed. Repression of dissenters.

Marries Elizabeth Minshull (Feb.). Moves to Bunhill Fields.

1663

Butler, Hudibras, Part I.

1664

Butler, Hudibras, Part II; Molière, Tartuffe.

Quaker Thomas Ellwood finds house for Milton at Chalfont St. Giles to escape plague.

1665

Bubonic plague kills 70,000 in London.Second Dutch War.

1666

Great Fire of London (Sept. 2–6). Bunyan, Grace Abounding.

Paradise Lost published.

1667

Dryden, Annas Mirabilis; Of Dramatick Poesie.

1668

Dryden made Poet Laureate.

Publishes Accidence Commenc’t Grammar.

1669

Publishes History of Britain, with William Faithorne’s engraved portrait.

1670

Publishes Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes.

1671

Publishes Art of Logic.

1672

Charles II’s Declaration of Indulgence.Marvell, Rehearsal Transposed.Third Dutch War.

Publishes Of True Religion, Hæresie, Schism and Toleration; publishes new edition of Poems (1645).

1673

Test Act passed.

Publishes Familiar Letters and Prolusions. Publishes 2nd edition of Paradise Lost. Death (Nov. 8–10?); burial at St. Giles, Cripplegate (Nov. 12).

1674

Dryden’s rhymed drama The State of Innocence, registered (published 1677).

1678

Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress.

4th (Folio) edition of Paradise Lost: illustrations chiefly by Juan Baptista de Medina, engraved chiefly by Michael Burghers.

1688

Milton’s Letters of State published, with Edward Phillips’ Life of Milton and four sonnets – to Fairfax, Cromwell, Vane, and Cyriack Skinner (#2) – omitted from 1673 Poems.

1694

Introduction

Milton’s rich and varied prose works remain among his great achievements as a writer; moreover, they address issues that remain compelling to a wide readership in the twenty-first century. His prose writings examine and grapple with such major topics as freedom of the press; religious toleration and liberty of conscience; divorce, gender, and marriage; political servility and idolatry; the dangers of tyranny and the nature of popular sovereignty; and the significance of political debate, dispute, and dissent. Milton published his own ideas about a strenuous and demanding education – articulated most thoroughly in his tract Of Education – that would have crucial implications for reforming his nation and help to make “a knowing people” capable of “searching [and] revolving new notions” and of “fast reading, trying all things, assenting to the force of reason and convincement” (Areopagitica, p. 207). Throughout his prose, Milton challenges comforting or stultifying religious orthodoxies and received opinions (he complains in Areopagitica about “the gripe of custom” and “a muddy pool of conformity and tradition”; pp. 211, 203), and he prompts engaged, discerning readers to question theological and political systems and to work out their beliefs for themselves. Most crucially his prose writings grapple with different kinds of liberty: religious, political, domestic, and individual. To be sure, as a controversialist, Milton’s various understandings of liberty need to be situated in relation to the tumultuous world of seventeenth-century England, especially the political and religious events and upheavals of the English Revolution and Restoration. Nonetheless, his challenging arguments about liberty and servility, animated by his vivid and rhetorically artful prose, continue to resonate in our own time.

Milton wrote some of the richest prose in the English language. Its linguistic and rhetorical variety is exceptional: Milton can write in the same text with great eloquence and learning and with graphic, satirical, and bawdy diction. His prose can be densely and vividly imagistic (as, say, in the cases of Of Reformation and Areopagitica) and it can tend toward plainness (as in the case of his late pamphlets A Treatise of Civil Power and Of True Religion). It can be fiery and prophetic and elsewhere it can be characterized by exegetical analysis and make “well temper’d” (The Reason of Church-Government, p. 63), nuanced arguments. It used to be said that Milton wrote his prose with his “left hand,” a phrase Milton himself employs in the great vocational digression to The Reason of Church-Government.1 But more recent commentators have learned not to take Milton at his word here and to recognize that he does not always write “in the cool element of prose,” as though his prose were less literary than his poetry.2 The relation between his prose and poetry is more complex and interconnected than this. The lexical inventiveness, rhetorical variety, and metaphorical richness of Milton’s prose constantly remind us that it can be appreciated on an aesthetic level. Yet its aesthetic qualities give potent, memorable expression to the large issues Milton seeks to examine. For example, Milton’s most famous work of prose, Areopagitica, addresses, in richly figurative writing, the ways press censorship can affect the free circulation of ideas, the freedom of choice readers enjoy (thereby enabling their virtue to be tested), and the independence of authors during a period of political and religious crisis and warfare.

Much of Milton’s prose was written and published during decades of great political and religious upheaval and experimentation: the “tumultuous times” (The Reason of Church-Government, p. 88) of the English Civil Wars and the Interregnum, when religion and politics were inseparable. The English Revolution was a wordy revolution. It was fought not only on the military battlefield between royalists and Parliamentarians but with books and pamphlets, which poured out from the presses. Milton contributed actively – and imaginatively – to the vital textual dimensions of the English Revolution as he devoted “to this conflict all [his] talents and all [his] active powers” (Second Defence, p. 349). The annotations in this edition aim to illuminate the complex and shifting contemporary political and religious contexts in which Milton wrote and published his major prose works; the annotations also elucidate the wealth of Milton’s biblical, classical, and topical allusions. Yet, as I have suggested, our appreciation of Milton’s prose works need not be constrained by these contexts or by their rich allusiveness; they address significant controversial issues in ways that will continue to provoke and interest readers in the twenty-first century. In this introduction, I situate Milton in the rhetorical and polemical world of religion and politics in which he wrote most of his great prose, while keeping in mind that Milton’s prose works – and the manifold arguments they freshly make about liberty versus servility in the religious, political, and domestic spheres – remain compelling and important writings today. They may often require the engaged and strenuous efforts of reading Milton expects from active, discerning readers in his own age; however, his rhetorically varied prose works and the thought-provoking arguments they make reward such efforts.

Milton’s Anti-Episcopal Prose and Religious Conflict

Milton’s zealous antiprelatical prose in the early 1640s was stimulated by the collapse of the Church of England. Religious and political tensions increased during this period because of a number of major religious events and factors (see the Chronology [pp. xii–xiii] for some of these): godly or Puritan fears of increased popery within the established church and at court; the Root and Branch Petition (supported by 15,000 citizens) to abolish episcopacy, the system whereby churches were governed by bishops; the assault on the ecclesiastical order and the powerful Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud (impeached in December 1640), who promoted high-church ceremonies and “innovations”; the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion in October 1641; the Grand Remonstrance (an apocalyptic manifesto defining Parliament’s grievances against King Charles I and his ministers); debates about matters of church government and liturgy; the increase of Puritan militancy and the desire for godly reformation; and the escalation of apocalyptic rhetoric stimulated by the political and religious crisis. With its ornate vestments, elaborate rituals, emphasis on the sanctity of the altar, elevation of the bishops, and devaluation of preaching and Bible reading, the Church under Laud had asserted its splendor and authority in idolatrous ways that struck Milton as nothing less than popery. In the midst of these heated developments, and on the threshold of civil war, Milton produced his combative anti-episcopal tracts (1641–2), including Of Reformation and culminating with The Reason of Church-Government and An Apology against a Pamphlet.

Milton’s militant Protestantism, fiery prose, and aggressive polemic are evident throughout the early prose tracts where he justifies using “a sanctifi’d bitternesse against the enemies of truth” (An Apology, p. 101). Of Reformation (May 1641) is infused with violent millenarian rhetoric and graphic imagery inspired by the Book of Revelation: there Milton introduces the startling image of the bishops giving “a Vomit to GOD himselfe” (a more graphic rendering of Revelation 3:16: “I will spue thee out of my mouth”), envisions the “shortly-expected King,” and relishes the apocalyptic destruction of the Laudian prelates “throwne downe eternally into the darkest and deepest Gulfe of HELL” (pp. 29, 60). Zeal and art often reinforce each other: in An Apology against a Pamphlet (April 1642), Milton takes “leave to soare…as the Poets use” as he envisions Zeal ascending his fiery chariot “drawn with two blazing Meteors figur’d like beasts” (p. 100). This vivid and elaborate apocalyptic passage – inspired by the visionary chariot of Ezekiel I and anticipating the Son’s apocalyptic chariot in Paradise Lost, Book VI – reveals how Milton’s visionary prose could express heated fervency and a poetics of vehemence as he waged polemical warfare against the Laudian episcopacy: “the invincible warriour Zeale shaking loosely the slack reins drives over the heads of Scarlet Prelats…brusing their stiffe necks under his flaming wheels” (p. 100). Later, in the divorce tracts, Milton admires the contentious Christ who responds to the Pharisees with vehement rhetoric and “the trope of indignation” (CPW, II, 664), evidence again of the literary and poetic ways in which Milton conceived vehement polemic.

Scornful laughter, derision, and vehemence are among the most notable characteristics of Milton’s prophetic voice in the early controversial prose. The contentious polemicist justifies indignation, derides lukewarmness, and admires martyrs unsparing in their derision of their superstitious persecutors. Sustained mockery and satire of the clergy are among the polemical weapons Milton skillfully exploits; thus, having been accused by one of his polemical attackers, the Modest Confuter, of having visited playhouses and bordellos, Milton strikes back in An Apology by scornfully recalling the pretentious future divines foolishly “prostituting” themselves as they overacted in bad stage performances before courtiers:

in the Colleges so many of the young Divines, and those in next aptitude to Divinity have bin seene so oft upon the Stage writhing and unboning their Clergie limmes to all the antick and dishonest gestures of Trinculo’s, Buffons, and Bawds; prostituting the shame of that ministery which either they had, or were nigh having, to the eyes of Courtiers and Court-Ladies, with their Groomes and Madamoisellaes. There while they acted, and overacted, among other young scholars, I was a spectator; they thought themselves gallant men, and I thought them fools. (p. 96)

The zealous Puritan writer relishes this memory and exploits it for polemical ends as he scorns Laudian prelates who appeal to shows of outward worship, elaborate vestments, and ceremonial religion.

The crisis in religion in the early 1640s manifested itself in an extensive literature about church government. The longest of Milton’s antiprelatical tracts, The Reason of Church-Government (published in early 1642), opposes forms of episcopal power and church hierarchy by responding to Certain Briefe Treatises…Concerning the Ancient and Moderne Government of the Church (1641), a collection of essays assembled by the formidable scholar of episcopacy and its history, Archbishop James Ussher. A complex work of religious controversy, Milton’s Church-Government weaves together public religious polemic and personal vocational testimony. Like the previous anti-episcopal tracts, it is fiercely anti-Laudian; whereas Laud stressed that “the external worship of God…might be kept in uniformity and decency, and in some beauty of holiness,”3 Milton asks: “Did God take such delight in measuring out the pillars, arches, and doores of a materiall Temple, was he so punctuall and circumspect in lavers, altars, and sacrifices soone after to be abrogated?” (p. 67). Such innovative ceremonialism and sacramental worship fueled deep religious divisions in the nation. Milton’s emphasis is not on external worship. Instead, he emphasizes a church built on self-discipline arising from the authority of the Word and the Spirit; consequently, he says little – and certainly less than his anti-episcopalian Presbyterian allies might like – about a visible church with ministers, lay elders, and national synods responsible for formulating policy. A Presbyterian-style government is clearly less important to Milton than individual piety. True discipline does not encourage “cloyed” repetition or ceremonial observance. So Milton suggests in an elaborate metaphorical passage that draws upon the language of planetary orbits: “Yet is it not to be conceiv’d that those eternall effluences of sanctity and love in the glorified Saints should by this meanes be confin’d and cloy’d with repetition of that which is prescrib’d, but that our happinesse may orbe it selfe into a thousand vagancies of glory and delight” (p. 65). Milton’s astronomical language about “vagancies” or deviations and eccentricities within the church anticipates one of his most polemical points: his provocative defense of sectarianism.

Indeed, not only were the prelates fueling fears of religious divisions, but the mainstream godly – i.e., the Presbyterians – were becoming increasingly alarmed by the fragmentation of zealous Protestantism and its more radical manifestations; within a few years large catalogues of sects and popular heresies would appear (Milton the “divorcer” was regularly mentioned among them), including Ephraim Pagitt’s Heresiography (1st edn, 1645) and Thomas Edwards’s popular Gangraena (1646). Milton’s Church-Government deflates these fears – “If we go downe, say you, as if Adrians wall were broke, a flood of sects will rush in. What sects? What are their opinions? give us the Inventory” – but responds in a way that would hardly assuage the concerns of the mainstream godly who were keen on a national church: “Noise it till ye be hoarse; that a rabble of Sects will come in, it will be answer’d ye, no rabble sir Priest, but a unanimous multitude of good Protestants will then joyne to the Church, which now because of you stand separated” (p. 79). Church-Government thus anticipates Milton’s spirited defense of sectarianism and revolution a few years later in Areopagitica.

Church-Government, however, is also memorable because of its striking autobiographical digression in the preface to its second book. Milton’s vocational and personal crises are interconnected with the religious and political crises of the revolutionary years. Milton justifies the vehement character of his controversial prose – “sharp but saving words” – as he compares himself to the sad prophet Jeremiah and speaks about the burden of the prophetic, zealous writer who must issue jarring blasts during tumultuous times. Nevertheless, he is also anxious about this burdensome prophetic vocation and about interrupting “a calme and pleasing solitarynes,” including the “quiet and still air of delightfull studies,” to engage in the “hoars disputes” (pp. 86, 91) of occasional polemic.4 He is sensitive about his age – his “green yeers” – and about being relatively unknown, particularly as he engages in polemical struggle with “men of high estimation” in the Church of England, including Joseph Hall, James Ussher, and Lancelot Andrewes. Struggling with his own divided impulses, he deprecates his poetry (“a vain subject”), especially at an urgent time when “the cause of God and his Church was to be pleaded,” and he deprecates his prose writing – he sits “below in the cool element of prose,” the product of his “left hand” (pp. 87, 88) – as more earthbound than the sublime conceits of the visionary poet. Yet, as we have already seen, the controversialist in fact often holds his pen in his right hand – for example, in the sublime passage from an Apology envisioning the fiery chariot of Zeal. Indeed, just after apologizing for his poetry and despite the fact that “time servs not now,” he launches into an elaborate literary autobiography (one of the major statements of Milton’s literary ambitions) that reveals his desire to “leave something so written to aftertimes, as they should not willingly let it die” (pp. 89, 88), possibly in the form of epic. Inspired by the prophet Isaiah, Milton is a poetic vates (he alludes to Isaiah 6:1–7 as he does in his precocious Nativity Ode of 1629). He finds himself politically engaged in the religious upheavals of the early 1640s and imagines writing inspired national poetry, including “Dramatick constitutions… doctrinal and exemplary to a Nation,” as well as poetry deploring “the general relapses of Kingdoms and States from justice and Gods true worship” (pp. 89, 90): and so he would in Samson Agonistes and in Paradise Lost (notably in the epic’s final historical books). Milton complains in Church-Government about “the necessity and constraint” (p. 91) imposed by the present moment and the cool element of prose, yet the political/religious crisis had stimulated him to envision a great poetic future and to articulate in polemical prose that highest of literary enterprises.

The Politics of Divorce and “Free Writing”

As a controversialist, Milton also dared to defend unorthodox beliefs when it came to domestic liberty. As a result of producing four divorce tracts in 1643–5 – including The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce – he was condemned before Parliament in a sermon by the minister Herbert Palmer (in August 1644) and regularly labeled heretical in anti-sectarian writings by the orthodox godly who feared he was destroying the marriage bond and hence the social fabric. The attacks only pressed Milton more firmly toward the camp of the Independents who tolerated diversity of practice and belief and who therefore opposed Presbyterianism (and the recently established Westminster Assembly of Divines). By addressing his first three divorce tracts to Parliament, Milton was politicizing the controversial issue of divorce and stressing interconnections between the tragic yoke of bondage in the household estate and the danger of the godly commonwealth: “For no effect of tyranny can sit more heavy on the Common-wealth, then this houshold unhappines on the family” (p. 109).

The divorce tracts again show how personal and political crises could intersect in Milton’s career: Milton’s wife Mary Powell had deserted him in August 1642 (she did not return until 1645) and this triggered a personal crisis which assumed national proportions. A mixture of exalted idealism and anguished bitterness, the divorce tracts concern themselves with domestically liberated Englishmen (rather than women) as Milton depicts the bondage and despair of an unfit, unhappy marriage as “a drooping and disconsolate household captivitie, without refuge or redemption” (p. 111) – especially for the tragic husband. Engaged in strenuous scriptural hermeneutics, Milton the Protestant exegete attempts to reconcile contradictory scriptural passages – the wise, charitable Mosaic law condoning divorce (in Deuteronomy 24:1) and Christ’s abolition of Old Testament legislation (in Matthew 5:32 and 19:3–11) – but Milton’s heroic efforts only highlight irreconcilable tensions. The patriarchal gender politics of the divorce tracts have made them the subject of intense critical interest.5 Yet however we interpret them to situate Milton’s complex and sometimes contradictory views of gender and sexuality, we need to remember that the divorce tracts were also products of the tumultuous English Revolution and thus exceptionally daring texts which further radicalized their author – a dangerous heretic in the eyes of orthodox Puritans who feared that, with the breakdown of censorship and the growth of sectarianism, the errors of the times (“damnable doctrines”) expressed in such wicked books were fueling political and religious anarchy.6

In the midst of the divorce controversy, Milton was intensely concerned with the capacity of printed texts to shape the major debates of the English Revolution. Censorship had collapsed with the abolition of the feared Star Chamber (July 1641) – one of those “Courts of loathed memory” (p. 79) – and the overthrow of the bishops’ authority, stimulating an ever increasing outpouring of printed texts; between 1641 and 1645 nearly 10,000 titles appeared in Britain and more than 8000 were published in London alone.7 The Long Parliament’s Licensing Order of June 1643, however, was an attempt to reintroduce a system of press censorship. Printed unlicensed and unregistered, Milton’s Areopagitica offered a spirited challenge to pre-publication censorship (so that books can be held accountable after publication) and conveyed a new, invigorated sense of authorship stimulated by the political and religious upheavals of these revolutionary years. Authors and their newly empowered readership were actively shaping political debate, as more and more political writings poured out from the presses. These printed texts helped to shape opinions in a radical direction as authors debated issues of popular sovereignty, the supremacy of Parliament, the right of resistance, and the nature of religious toleration, among other urgent topics. Milton captured the exhilarating ferment of “all this free writing and free speaking” in Areopagitica (p. 209). Revolutionary London, “the mansion house of liberty,” itself became in Milton’s visionary prose a great “shop of warre . . . in defence of beleagur’d Truth” – the center of intellectual energy and ideological warfare where “new notions and idea’s” (p. 207) were rapidly being generated and circulated by the press.

The dense figurative prose of Areopagitica, which interweaves and reinvigorates classical myths and biblical language, conveys the sense of political excitement and religious diversity unleashed by the English Revolution, as well as a heightened sense of millenarian expectations (i.e., that Christ’s kingdom was at hand). Yet Milton handles these issues with fresh complexity and nuance. He writes poignantly about the dismemberment of “our martyr’d Saint” Truth – evoking the Star Chamber mutilation of Puritan martyrs in the late 1630s – as he explores themes of political fragmentation and unity: he not only urges Parliament to engage in the active search for Truth (as “Isis made for the mangl’d body of Osiris”), but reminds its members that the pieces of her lovely body will not be fully reassembled until “her Masters second coming” (pp. 206, 205). Milton’s vision of strenuously and artfully building the Temple of the Lord highlights, moreover, that building unity in the chosen nation of England will not be accomplished without “many schisms and many dissections.” Religious truth may, paradoxically, be both one and disparate, various yet homogeneous; or to invoke a Miltonic double negative from Areopagitica, it is “not impossible that she may have more shapes than one” (pp. 208, 210).

And this brings us to one of the ways in which Milton’s Areopagitica offers a distinctive interpretation of religious toleration in his age. If we consider toleration as “defined as the peaceful coexistence of people of different faiths living together in the same village, town, or city,” or nation, then Milton’s robust and imaginative vision goes one step further. Most early modern Europeans, after all, would have used the word “tolerate” in its traditional meaning: “to suffer, endure, or put up with something objectionable.”8 But Milton views toleration for the sects as more than a situation of stable coexistence and more than a matter of managing or containing conflicts between religious groups. In Areopagitica he sees it as a kind of dynamic coexistence that can re-energize a nation in its ongoing process of reformation and re-forging itself. Radical sectarians, despite contemporary orthodox fears, were among the many pieces contributing to the new “spirituall architecture” of the godly nation (p. 208). England at this revolutionary moment was indeed “a noble and puissant Nation” – rousing herself like Samson and “shaking her invincible locks” (p. 209) – and Milton was its fiery prophet in his new age of exhilarating reformation.

The Politics and Writing of 1649

The crisis of 1649 would challenge the exhilarating vision of Areopagitica as Milton harnessed his talents as a controversial prose writer in service of the experimental republic. The year 1649 was one of climatic revolutionary upheaval. It was preceded by the purging of Parliament (December 6, 1648), thereby creating the Rump Parliament, and followed by the regicide (on January 30), the abolition of kingship and the House of Lords (in March), and establishment of the republic. These traumatic events were supported by many religious radicals and vigorously defended by Milton in his controversial prose works. Yet it was also a year of acute internal tensions as Leveller agitation in the Army and press posed a serious internal challenge to the Rump and new republic established by a coup d’état and lacking popular support.9

Published soon after the execution of King Charles I, The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (February 1649) presented a vigorous defense of revolution, tyrannicide, and republican beliefs (drawing, in part, on classical republican sources), as well as an assault on the counter-revolutionary politics of the Presbyterians. Here Milton insisted, much like the Levellers, that “the power of Kings and Magistrates is nothing else, but what is only…committed to them in trust from the People…in whom the power yet remaines fundamentally”; and with marvelous bluntness he defended natural rights and liberties since no one “can be so stupid to deny that all men naturally were borne free” (pp. 243, 249). Yet Milton, viewing the dramatic revolutionary events as an opportunity for political change, does not attempt to reconcile the contradiction between the regime’s claim that the people are “the original of all just power”10 and the fact that the Rump Parliament and the Army were by no means representative bodies. Instead, his most pungent prose derives from his polemical engagement with the shifting Presbyterians who had “juggl’d and palter’d with the world” in an equivocal way (p. 246; echoing Shakespeare’s Macbeth V, viii, 19–22): they had first waged zealous war against the king during the 1640s, their fiery preachers invoking the curse upon Meroz in the Song of Deborah (Judges 5:23) against those who did not oppose Charles I; and then they turned around and sought to reconcile themselves to him later in the decade, supporting negotiations with the king (who had agreed to accept Presbyterian religion in Scotland and establish it in England) and inciting sedition against the Rump Parliament. The Presbyterians, after all, had claimed their “discipline” was more demanding than the episcopal government they rejected: so why, Milton scornfully asks, were they absolving the king “though…unrepentant” (p. 263)? Milton’s polemical strategy in The Tenure (reinforced in the second edition published before February 15, 1650) involves citing eminent Protestant authorities – including the zealous sixteenth-century John Knox, the original defender of regicide – to blast the present-day prevaricating divines who have assumed their “new garbe of Allegiance” (p. 247). In one striking passage he describes the doubling divines as “nimble motionists,” London militiamen who easily shift ground with “cunning and dexterity” for their own political advantage-taking; they invoke Providence, as godly preachers and soldiers regularly did during the Civil War years, though in this case to justify equivocal means and covetous ends:

For Divines, if ye observe them, have thir postures, and thir motions no less expertly, and with no less variety then they that practice feats in the Artillery-ground. Sometimes they seem furiously to march on, and presently march counter; by and by they stand, and then retreat; or if need be can face about, or wheele in a whole body, with that cunning and dexterity as is almost unperceivable. (pp. 271–2)

Milton’s military trope vividly conveys the doubleness of their behavior throughout the turbulent Civil War years as he describes these guileful, serpentine clergymen who “winde themselves” into different positions. Their former revolutionary zeal and Puritan militancy, just like their various postures, seemed no less calculating. Milton’s attack on counter-revolutionary politics in The Tenure no doubt helped to secure his official appointment in March 1649 as the Secretary to Foreign Tongues to the Council of State and as propagandist for the experimental republic.

Milton’s most challenging polemical assignment during 1649, however, was to shatter the popular image of the martyred king projected in Eikon Basilike: The Portraiture of His Sacred Majesty in His Solitudes and Sufferings, copies of which circulated on or close to the day of the king’s execution (January 30). The most important book of royalist propaganda in its age, the king’s book (very likely co-fashioned by the divine John Gauden) went through thirty-five English editions in 1649 and twenty-five elsewhere in Europe; its appeal confirmed widespread traditional sentiment for the monarchy and the narrowly based support for the new Commonwealth. One of those “shrewd books, with dangerous Frontispices” (Areopagitica; p. 196), Eikon Basilike presented the martyred King Charles as a patient Davidic and Christic figure, suffering yet constant in the midst of dark, turbulent revolutionary times; its famous frontispiece by William Marshall showed the pious king kneeling at his prayers in a basilica, gazing at the heavenly crown of glory, while holding the crown of thorns, setting aside his own crown, and treading underfoot the things of this world (see Fig. 2; p. 274). Milton’s lengthy response, Eikonoklastes (October 1649), attempted to demolish the king’s seductive words and artful image, thereby demystifying the potent language and iconicity of monarchy and the political servility it engendered.

In Eikonoklastes, the radical Puritan Milton is scornful of the “Image-doting rabble” who have easily fallen for the king’s book and the clever device of the frontispiece. Milton believes that servility is not the natural inclination of the English people; and yet the people, irrational and inconstant in their judgments, are in danger of being seduced again. Recalling themes of dangerous enchantment first dramatized in his Masque presented at Ludlow Castle (1634), Milton depicts the king’s book as a form of Circean “Sorcery” that has bewitched the credulous people who have run into “the Yoke of Bondage” (p. 317; CPW, III, 488). Such is the enticing power of royalist representation. Milton’s Eikonoklastes is a vigorous attempt, through verbal polemic, to break to pieces the religious image of the king, as well as to expose the “glozing words” sustaining the “illusions of him” (CPW, III, 582). Milton aims to expose the disjunction between seductive image and dangerous reality, between the king’s “fair spok’n words” and “his own farr differing deeds” (p. 281); under his mask of martyrdom and behind his “cunning words” (p. 316), the guileful Stuart king resembles the theatrical Satan of Paradise Lost: he is willful, revengeful, unrepentant, guilty of prevaricating, full of rage and malice, imperious and violent. Milton’s Eikonoklastes encourages its readers to be vigilant, discerning, and skeptical – to question the seductive images and language that can “putt Tyranny into an Art” (p. 280).

Defending the English People and Himself

Milton was soon ordered by the republic’s Council of State to wage his republican polemical warfare in a wider, international context: the result was his most sustained vituperative prose polemic, his Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio (A Defence of the English People; February 1651), the first of three Latin Defences he wrote during the Interregnum. Milton was especially proud of A Defence, for there he took on one of the most famous European classical scholars, Claude Saumaise or Salmasius, author of Defensio Regia pro Carlo I (1649). The frontispiece of Milton’s text (see Fig. 3, p. 318), displaying its two symbols of the shield with a cross and harp, conveyed multiple, intersecting meanings associated with its author as a prose polemicist during the Interregnum: the chivalric defender of England (like St George) was now using his literary, prophetic talents (the harp evokes the figures of Orpheus and the prophet David) to defend the republic against its enemies at home and abroad. Milton’s republican Defence was immensely successful: although publicly burned in France, it won praise from the Low Countries to Greece; Milton felt particularly vindicated in his polemical battle after the Protestant Queen Christina of Sweden, exemplifying her “vigorous mind” (p. 343), expressed admiration for his Latin defense. From a rhetorical standpoint, however, Milton’s most varied, brilliant, revolutionary defense was yet to come.

Having routed the famous Salmasius and exhilarated by the success of his first Defensio, Milton continued to wage polemical warfare on an international front with his next and most skillful defense, a vigorous response to the anonymously published Regii Sanguinis Clamor ad Coelum (August 1652) or The Cry of the Royal Blood to the Sky, a reply to Milton’s Defensio by the English clergyman, Peter du Moulin. The republican attacker of the martyred king and great Salmasius (likened to “our French Hercules”) had been viciously maligned as a vile and obscure adversary, a depraved wretch, and a monstrous Polyphemus.11 By the time he was attacked in the Clamor, Milton was completely blind, a personal crisis he would struggle with in some of his greatest prose and poetry. Milton mistook the true author of Clamor and, needing to aim his polemic at a definable enemy, attacked instead its editor-publisher, Alexander More, again addressing his text to the European community at large. In his Second Defence of the English People (May 1654) Milton responded in a complex way in one of his richest prose works, offering a skillful mixture of invective, autobiographical self-justification, panegyric, and hard-nosed political advice. His tract celebrated the heroic achievements of a number of virtuous revolutionary leaders and godly parliamentarians, including the ardent republican John Bradshaw – President of the High Court of Justice which had daringly tried the king – and Oliver Cromwell himself, leader of the Protectorate, the new regime that assumed power at the end of 1653. The Second Defence became a polemical occasion for revolutionary mythmaking.

There Milton the controversialist presents himself as a fearless chivalric warrior who has, in his own way, borne arms in the mighty struggle for liberty and who compares himself to the epic poet creating a literary monument to extol the glorious deeds of his countrymen (p. 376). The Second Defence reveals Milton’s impulse to write an epic based not on legendary history (which, as a younger poet, he had planned to do), but upon the major actors and exhilarating events of the English Revolution: Milton presents the tireless Cromwell as a classical-style military hero, as pater patriae (“the father of his country,” the honorific title given to Romans, like Cicero, who performed outstanding service to the state) and as a Puritan saint known for his “devotion to the Puritan religion”; his exploits have outstripped not only those of English kings, but “even the legends of our heroes” (pp. 370, 368). At the same time, Milton, identifying his own personal crises and trials with those of Cromwell and the English nation, defends himself against royalist detractors who claimed that his blindness, which had become total by February 1652, was a sign of God’s judgment against a writer who had justified the regicide. Milton presents himself as un-reproachable, having conducted “a pure and honorable life” (p. 346); his blindness is a mark of sacredness and an occasion for internal illumination and for Milton to show strength “made perfect in weakness,” a Pauline phrase that became the blind writer’s personal motto. Like Cromwell, he remains “tireless” in his work (indeed, his work for the Council of State continued unabated during this period) and willing to risk great danger in his polemical combat (p. 337).

Milton also counters attacks on the new quasi-regal experimental government called the Protectorate, with its single-person executive, from disenchanted Independents and inflamed sectarians (the latter protested that King Oliver was usurping the role of King Jesus), as well as from religious Presbyterians who were fueling factions (“men who are unworthy of liberty most often prove themselves ungrateful to their very liberators” [p. 375]). However, despite working for the new regime, Milton does not hesitate to issue advice and stern warnings to his fellow compatriots and to Cromwell himself: although hard won through warfare and the traumatic events of the English Revolution, political liberty remains vulnerable; it must be vigilantly defended as arduous trials – including internal struggles – lie ahead in times of peace. Milton urges Cromwell and his countrymen to separate church and state, reduce and reform laws, see to the education and morals of the young, allow free inquiry and a more open press, protect free conscience, refrain from factions, and resist succumbing to “royalist excess and folly,” as well as other vices which would enable corrupt, incompetent men to assume power and influence in the government (p. 374). The Second Defence skillfully balances panegyric with warning, and with a realistic assessment of the precarious political situation.

Milton’s Late Prose and the Crisis of the Good Old Cause

After the verbal mud-slinging of his final defense (his Pro Se Defensio of 1655, a tract further devoted to attacking Alexander More), Milton did not engage in public prose polemic until the final, unstable two years of the Interregnum. After the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, there followed a period of political flux and further upheaval: the Protectorate under Richard Cromwell (Oliver’s son) antagonized the Army and radical Independents and sectaries, and therefore was short-lived; the Rump returned to power in May 1659, but was no more popular than before and proved ineffective; General George Monck (commander of the Army in Scotland) marched into London in February 1660 and reassembled the Long Parliament which met and dissolved itself in mid-March 1660; with mounting popular enthusiasm for the king’s cause, the new elected parliament summoned Charles II from exile in May 1660. Despite the conservative, backsliding trends of these late Interregnum years and the failure of the republican “Good Old Cause,” Milton’s radical religious and political voice remained “unchang’d / To hoarse or mute” (Paradise Lost, VII, 24–5); indeed, in some ways it became more radical.

The companion texts he published in 1659 highlight his radical religious and anti-formalist convictions. Published in February of that year and addressed to the conservative Puritan Parliament of Richard Cromwell, A Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Causes reveals Milton’s radical Protestantism by vigorously challenging ecclesiastical and political powers in relation to spiritual matters and inward religion: no church or civil magistrate should employ outward force to constrain inward conscience or faith. Inwardness has become Milton’s touchstone of integrity and his polemical strategy involves his own “free and conscientious examination” (p. 389) of divisive religious terms which had sharply aggravated tensions during the revolutionary years. There he diffuses, as he does in Areopagitica and would likewise do in Of True Religion (1673), the explosive and stigmatizing terms “heresie and heretic” – “another Greek apparition” – by defining a heretic freshly: one who maintains the traditions of men or opinions not supported by Scripture; heresy therefore means professing a belief contrary to one’s conscientious understanding and strenuous engagement with Scripture (p. 383). Moreover, Milton’s emphasis in Civil Power on the guidance of “inward perswasive motions” of the Spirit (p. 390), which takes priority over Scripture itself in leading to spiritual Truth, reminds us of his close relations to contemporary religious radicals – the Quakers among them – who were following the impulses of the Spirit within, while anticipating the radical spiritualism of the great poems: the “strong motions” by which Jesus is led into the wilderness in Paradise Regained (I, 290), or the “rouzing motions” (line 1382) Samson feels just before he destroys the idolatrous Philistine temple of Dagon in Samson Agonistes. Civil Power is marked by its emphasis on internal illumination, by Milton’s concise uses of scriptural proof texts to emphasize our freedom from ceremonies and the servile laws of men, and by the plainness of its style, meant to reinforce Milton’s polemical rejection of the learned ministry: for, as he puts it in a paradoxical formulation about who is “learned,” “doubtless in matters of religion he is learnedest who is planest” (p. 397).

Milton the radical Protestant did not join a separate congregation or sect, and he remained staunchly opposed to any national church. Civil Power and The Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings (August 1659) are notable for neglecting the role of the church in Protestant experience. Milton’s biting attack on the hireling clergy as wolves and “greedy dogs” (p. 411; echoing Isaiah 56:11), as well as his firm rejection of tithes (tax payments of one-tenth of income by the laity to the church) in order to maintain a national established ministry is close indeed to the concerns of radical sectarians, including those like the Quakers who publicly reviled the orthodox, university-trained clergy as hirelings for making a trade of their preaching. Tithes became one of the most contentious issues of the English Revolution; religious radicals, including Milton, argued that they had lost their divine sanction when the ceremonial Law was superseded by the Gospel and the Levitical priesthood by an apostolic ministry. Yet while attacking a hireling clergy and their “seeming piety” (p. 403), Milton never specifically invokes the example and writings of contemporary Quakers (who modeled themselves upon the Apostles) or other sectarians; rather, he asserts his own polemical independence and authority, as he likewise does in his heterodox theological treatise, De Doctrina Christiana, where he sets out to establish his independent thinking by eschewing human authorities and by emphasizing his own strenuous exertions as he engages with Scripture. Milton preferred an inwardly inspired ministry, but to remove hirelings and find ministers prepared to preach the Gospel gratis (as St Paul did), he tersely remarks in Likeliest Means