6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

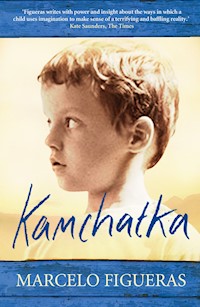

Winner of the 2012 Premio Valle Translation Prize Shortlisted for the 2011 INDEPENDENT FOREIGN FICTION PRIZE In the forecourt of a petrol station outside of Buenos Aires, a father says goodbye to his son: 'Kamchatka,' he whispers softly into his ear. And then they part, forever. A ten-year-old boy lives in world of Superman comics and games of Risk - a world in which men have superpowers and boys can conquer the globe on a board game. But in the outside world, a military junta have taken power; and amid a political climate of fear and intimidation, people are beginning to disappear without trace... Kamchatka is a heartbreaking novel; set in Argentina during the bloody coup d'etat of 1976, it tells the enchanting story of a young boy trying to make sense of a world during a time of extraordinary upheaval.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

KAMCHATKA

Marcelo Figueras, born in Buenos Aires in 1962, is a writer and a screenwriter.

Kamchatka

Marcelo Figueras

Translated from the Spanish by Frank Wynne

First published in the Spanish language in 2003 by Santillana Ediciones Generales, SL.

First published in English translation in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Marcelo Figueras, 2003

Translation copyright © Frank Wynne, 2010

The moral right of Marcelo Figueras to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Frank Wynne to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84354 827 0 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 361 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

First Period: Biology

1. The Last Word

2. All Things Remote

3. I am Left with no Uncles

4. An Inconvenient Patriarch

5. A Scientific Digression

6. Fantastic Voyage

7. Enter Bertuccio

8. The Principle Of Necessity

9. The Rock

10. A Short Family Parenthesis

11. Let’s Go

12. The CitrËn

13. Enter The Midget

14. Blind in the Face Of Danger

15. What I Knew

16. Enter David Vincent

17. Night Falls

18. Sirens

Second Period: Geography

19. ‘Ours was the Marsh Country’

20. The Swimming Pool

21. The Mysterious House

22. I Find Treasure

23. Houdini Escapes . . .

24. Fugitives

25. We Assume New Identities

26. Strategy And Tactics

27. We Find a Dead Body

28. A Peaceable Interregnum

29. We Find Ourselves Alone

30. A Decision At Dawn

31. A Foolproof Plan

32. Cyrus and the River

33. What they knew

34. The Matilde Permutation

35. The Experiment Fails

36. Monsters

37. The Ice Maiden

38. The Deadly Surprise

39. Accident And Emergency

Third Period: Language

40. Enter Lucas

41. A House Possessed

42. In Praise Of Words

43. Lucas Has a Girlfriend

44. I am Found out

45. I am Delivered up to a Tribe of Cannibals

46. Among The Beasts

47. I Learn To Breathe

48. An Unfinished Song

49. In Which I Discover that Someone I love very much is not Perfect

50. Shame

51. In Which I Become a Man of Mystery

52. Mister Corpuscle

53. The Fortress of Solitude

54. This Year’s Model

55. I Find Myself in the Middle of A 3-D Movie

56. Not Single Spies, but in Battalions

57. A Piece of bad News Turns out to be Good

58. A Picnic In The Rain

59. The Most Treacherous Season

60. Heaven Helps me Hold My Breath

61. On the art of the Milanesa

62. WE Receive An Announcement

63. The Right Questions

Fourth Period: Astronomy

64. Dorrego

65. In Which we Visit the Farm and I become a Foreign Correspondent

66. The Larvae

67. Grandma’s Time Machine

68. A Trip To Atlantis

69. In which I Play the spy and Hear Something I Shouldn’t

70. Of The Stars

71. In Which we Contemplate the Stars and Discover More Things than can be Contained Within this Chapter Title

Fifth Period: History

72. Concerning (Un)Happy Endings

73. Concerning The Best Stories

74. In which we Return Home, to Find Nothing But Darkness

75. In Which I make my Debut as an Escape Artist

76. In Which we Play Risk and I turn the Tables – Well, Almost

77. A Vision

78. In which Houses Crumble

79. The Principle of Necessity II

80. In which some Loose ends are Tied Up

81. Kamchatka

Acknowledgements

It is not down on any map; true places never are. Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

KAMCHATKA

First Period: Biology

Noun: the study of living organisms.

1

THE LAST WORD

The last thing papá said to me, the last word from his lips, was ‘Kamchatka’.

He kissed me, his stubble scratching my cheek, then climbed into the Citroën. The car moved off along the undulating ribbon of road, a green bubble bobbing into view with every hill, getting smaller and smaller until I couldn’t see it any more. I stood there for a long while, my game of Risk tucked under my arm, until my abuelo, my grandpa, put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Let’s go home’.

And that’s all there is.

If you want, I can give you more details. Grandpa used to say God is in the details. He used to say a lot of things, like ‘What Piazzolla plays isn’t tango’ and ‘It’s just as important to wash your hands before you pee as afterwards – you never know what you’ve been touching’, but I don’t think those things are relevant.

We said our goodbyes on the forecourt of a petrol station on Route 3, a few kilometres outside Dorrego in the south of Buenos Aires province. The three of us had had breakfast in the station café, croissants and café con leche in bowls as big as saucepans, with the petrol company logo on them. Mamá was there too, but she spent the whole time in the toilet. She’d eaten something that had upset her stomach and she couldn’t even hold down liquids. And the Midget, my kid brother, was asleep, sprawled on the back seat of the Citroën. He wriggled his arms, his legs, all the time while he was asleep, as though staking his claim, a king of infinite space.

At this moment, I am ten years old. I look normal enough apart from an unruly tuft of hair that sticks up like an exclamation mark.

It is spring. In the southern hemisphere, October days shimmer with golden light and today is no exception; the morning is a palace. The air is filled with fluttering panaderos – dandelion seeds, those daytime stars that in Argentina we call panaderos – or little bakers. I catch them in my cupped palms and, with a puff of breath, set them free again, urging them on to fertile ground.

(The Midget would crack up if he heard me say: ‘The air is filled with fluttering panaderos’. He’d roll on the ground, clutching his belly, laughing like a lunatic as he imagined tiny men, their brown and white aprons covered in flour, floating like bubbles.)

I can even remember the other people at the petrol station. The petrol pump attendant, a chubby man with a moustache and dark armpits. The driver of the IKA truck, counting a fat wad of banknotes as big as bed sheets on his way to the toilet. (I guess grandpa’s maxim about washing your hands before you pee is relevant after all.) The backpacker with the messianic beard, crossing the forecourt as he heads for the open road, his billycans clanking, like tolling bells calling to repentance.

The little girl sets down her skipping rope to go and wet her hair under the tap. She wrings it dry as she walks back, water dripping onto the dusty forecourt. The drops that just a moment earlier spelled out Morse code in the dust vanish as the seconds pass. Obedient to the call of gravity, they trickle down into the mineral particles, snaking through the spaces that exist where there seemed to be none, leaving behind some part of their moisture to give life to these particles even as they lose themselves on their journey towards the molten heart of the planet, the fire where the Earth still looks as it did when it was first formed. (In the end, we always are what we once were.)

Gracefully, the girl in front of me bends down and, for a minute, I think she is bowing. But in fact she’s picking up her skipping rope. She starts to skip again, a perfect rhythm, the rope whipping through the air, whup, whup, creating the bubble in which she hovers.

Papá opens the door to the station café and lets me go in; grandpa is already inside, waiting for us. His teaspoon creating a whirlpool in his café con leche.

Sometimes there are variations in what I remember. Sometimes mamá doesn’t get out of the Citroën until we leave the café because she’s busy scribbling something on her pack of Jockey Club cigarettes. Sometimes the numbers on the petrol pump run backwards instead of forwards. Sometimes the backpacker gets there before us and by the time we arrive he’s already hitchhiking, as though in a hurry to discover a world he’s never seen, the clank of his billycans pealing out the good news. These variations don’t worry me. I’m used to them. They mean I’m remembering something I hadn’t noticed before; they mean that I’m not exactly the same person I was when last I remembered.

Time is weird. That much is obvious. Sometimes I think everything happens at once, which is anything but obvious and even weirder. I feel sorry for people who brag about ‘living in the moment’; they’re like people who come into the cinema after the film has started or people who drink Diet Coke – they’re missing out on the best part. I think time is like the dial on a radio. Most people like to settle on a station with a clear signal and no interference. But that doesn’t mean you can’t listen to two or even three stations at the same time; it doesn’t mean synchrony is impossible. Until quite recently, people believed it was impossible for a universe to fit inside two atoms, but it fits. Why dismiss the idea that on time’s radio you can listen to the entire history of humanity simultaneously?

Every day, life gives us an intimation of this. We sense that, inside us, every ‘we’ we once were (and will be?) coexists: the innocent self-absorbed child, the sensual young man generous to a fault, the adult, feet planted firmly on the ground yet still clinging to his illusions, and finally we are the old man who knows that gold is just another metal; as his eyesight fails he has acquired vision. Sometimes, as I remember, my voice is that of the ten-year-old boy I was then; sometimes the voice of the seventy-year-old man I am yet to be; sometimes it is my voice, at the age I am now . . . or the age I think I am. Who I have been, who I am, who I will be are all in continual conversation, each influencing the other. That my past and my present together determine my future sounds like a fundamental truth, but I suspect that my future joins forces with the present to do the same thing to my past. Every time I remember, the person I was speaks his lines, performs his actions with increasing confidence, as though with each performance he grows more comfortable with the role, and understands it better.

The numbers on my petrol pump will start to go backwards. I can’t stop them.

Grandpa is back in his truck, one foot on the running board, softly singing his favourite tango: ‘decí por Dios qué me has dao, que estoy tan cambiao, no sé más quien soy’.

Papá leans down and whispers a last word into my ear. I can feel the warmth of his cheek as I could feel it then. He kisses me, his stubble rasping against my cheek.

‘Kamchatka.’

Kamchatka is not my name, but as he says it, I know he is thinking of me.

2

ALL THINGS REMOTE

‘Kamchatka’ is a strange word. My Spanish friends find it unpronounceable. Whenever I say it, they look at me condescendingly, as though they were dealing with some sort of savage. They look at me and they see Queequeg, the tattooed man from Melville’s novel, worshipping his little idol of some misshapen god. How interesting Moby-Dick would have been narrated by Queequeg. But history is written by the survivors.

I can’t remember a time when I did not know about Kamchatka. At first, it was simply one of the territories waiting to be conquered in Risk, my favourite board game, and the epic sweep of the game rubbed off on the place-name, but to my ears, I swear, the name itself sounds like greatness. Is it me, or does the word ‘Kamchatka’ sound like the clash of swords?

I am one of those people who always hunger for things remote, like Ishmael in Moby-Dick. The magnitude of the adventure is measured by distance: the more distant the peak, the greater the courage needed. In Risk, Argentina – the country where I was born – is on the bottom left of the board, just below the pink lines of the trade winds. In this two-dimensional universe, Kamchatka was the most distant place you could imagine.

At the start of our games, nobody ever fought for Kamchatka. The patriotic coveted South America, the ambitious looked to North America, the cultivated set their sights on Europe and the pragmatic set up camp in Africa and Oceania – easy to conquer and even easier to defend. Kamchatka was in Asia, which was too vast and consequently almost impossible to defend. And as if that wasn’t enough, Kamchatka isn’t even a real country: it exists as an independent nation only in the curious planisphere of Risk, and who wants to conquer a country that isn’t even real?

Kamchatka was left to me; I always had a soft spot for the underdog. To me, Kamchatka boomed like the drums of some secret savage kingdom, calling to make me their king.

At the time I knew nothing about the real Kamchatka, that frozen tongue Russia pokes into the Pacific Ocean, mocking its neighbours. I knew nothing about its eternal snows, its hundred volcanoes; I had never heard of the Mutnovsky glacier or the lakes of acid. I knew nothing of the wild bears, the fumaroles, the gas that bubbles up on the muddy surface of the thermal springs like pustules on a thousand toads. It was enough for me that Kamchatka was shaped like a scimitar and was utterly inaccessible.

Papá would be surprised if he knew how like the real Kamchatka is to the landscape of my dreams: a frozen peninsula, which is also the most active volcanic region on Earth. A horizon ringed by towering, inaccessible peaks shrouded in sulphurous vapours. Kamchatka is a paradox, a kingdom of extremes, a contradiction in terms.

3

I AM LEFT WITH NO UNCLES

On the Risk board, the apparent distance between Argentina and Kamchatka is misleading. When these flat dimensions are mapped onto a globe, this journey, which had seemed impossible, suddenly seems simple. There is no need to traverse the known world to get from one to the other. Kamchatka and the Americas are so close, they all but touch.

Similarly, the goodbyes we said on the forecourt of the petrol station and the beginnings of my story are superposed extremes, each nested inside the other. October sun melds with April sun, this morning blends with that one. It is easy for me to forget that one sun is the promise of summer and the other its farewell.

In the southern hemisphere, April is a month of extremes. Autumn begins and with it comes the cold. But the flurries of wind do not last and the sun always returns in triumph. The days are still long, some seem to have been stolen from summer. Ceiling fans begin their last shifts and people escape to the beach for the weekends as they try to outrun winter.

April 1976, in all its glory, was just like any other. I had just started sixth grade. I was trying to make sense of timetables, to decipher the lists of books I had to get hold of. I still packed more into my schoolbag than I needed and complained that I had to sit too close to Señorita Barbeito’s desk in class.

But some things were different. The military coup, for a start. Although papá and mamá didn’t talk about it much (they didn’t seem angry or upset, simply uncertain), it was obviously something serious. Meanwhile all my uncles were disappearing as if by magic.

Up until 1975, in our house in Flores, people came and went at all hours, talking and laughing loudly, thumping the table when someone said something interesting, drinking mate and beer, singing, playing the guitar and putting their feet up on the rocking chair as though they’d lived here all their lives. Most of them were actually people I’d never seen before and would never see again. When they arrived, papá invariably introduced them as ‘uncles’ and ‘aunts’. Tío Edward, Tío Alfredo, Tía Teresa, Tío Mario, Tío Daniel. We never remembered their names, but it didn’t matter. The Midget would wait for a few minutes, then amble into the dining room and, in his most innocent voice, say, ‘Tío, can I have a glass of Coke?’ Five men would leap to their feet to get it for him, and they would come back with glasses filled to the brim just in time for us to watch The Saint.

Towards the end of 1975, these uncles gradually began to disappear. Fewer and fewer of them visited us. They didn’t talk so loudly now; they didn’t laugh or sing anymore. Papá didn’t even bother to introduce them.

One day papá told me Tío Rodolfo had died and asked me to come with him to the wake. I said I would, because he’d asked me and not the Midget, given my superior status as older brother.

It was my first wake. Tío Rodolfo lay in the back room in an open coffin. The three or four other rooms were full of angry, single-minded people drinking sugary coffee and smoking like chimneys. I was relieved. I hate it when people cry, and I’d figured that everyone would be bawling their eyes out at a wake. I remember talking to Tío Raymundo (I’d never met him before; papá introduced us when we arrived). Tío Raymundo asked me about school, about where I lived and, without even thinking, I lied. I told him I lived near La Boca. I don’t know why.

Out of sheer boredom, I went over to look in the coffin and discovered that I did know Tío Rodolfo. His cheeks seemed a little more sunken, his moustache a little bigger, or maybe it just looked bigger because in death he appeared thinner, more formal, or maybe he just looked more formal because of the suit and the shirt with the wide collar, but it was definitely Tío Rodolfo. He was one of the few ‘uncles’ who had been to our house more than once and he had always made an effort to be nice to me and the Midget. The last time he visited, he’d given me a River Plate football shirt. When we got home from the wake, I looked in my wardrobe and there it was in its own coffin, second drawer from the bottom.

I didn’t even touch it. I shut the drawer and tried to put it out of my mind, but that night I dreamed the shirt had somehow crawled out of the drawer by itself, slithered over to my bed like a snake, wrapped itself around my neck and tried to choke me. I had that dream several times. And every time I woke up, I felt stupid. How could a River Plate shirt strangle me when I wasn’t even a River Plate supporter?

There were other signs too, but this was the most frightening. Fear had taken root in my own house, in my drawer, carefully folded, smelling of fresh laundry, nestling among the socks.

I didn’t ask papá what Tío Rodolfo died of. I didn’t need to. You don’t die of old age when you’re thirty.

4

AN INCONVENIENT PATRIARCH

My school was called Leandro N. Alem, after the gentleman who glowered down at us from the gloomy portrait every time we were sent to the headmaster’s office. The school was a nineteenth-century building on the corner of Yerbal and Fray Cayetano, opposite the Plaza Flores in the heart of one of Buenos Aires’ most traditional neighbourhoods. It was a two-storey building set around a central courtyard lit by a skylight whose shabby marble staircase bore witness to the generations who had taken it in their ascent to Learning.

It was a public school: its doors were open to everyone without distinction. For a small monthly fee, anyone could come to class, get a mid-morning snack and participate in sporting activities. For this notional fee we were granted access to the engine room of our language and to mathematics, the language of the Universe; we were taught where on the globe we were situated, what lay to north, to south, to east and west; what pulsed beneath our feet in the igneous core of the Earth, and above our heads; and before our virgin eyes unfolded the history of humankind, the history of which, for better or worse, we were at that time the culmination.

It was in these high-ceilinged classrooms with their creaking floors that I first heard a story by Cortázar and first opened Mariano Moreno’s Plan Revolucionario de Operaciones and learned of the part it played in our independence. In these classrooms I discovered that the human body was the most perfect machine and thrilled at the elegant solution to some problem in arithmetic.

My class could have served as a model for any campaign promoting peace among the peoples of the Earth. Broitman was a Jew. Valderrey had a thick Spanish accent. Talavera was two generations removed from his black ancestors. Chinen was Chinese. Even those boys who were more typically Argentinian – a mix of Hispanic, Italian and indigenous tribes – were noticeably dark-skinned. Some of us were the sons of professionals, others of working men with no education to speak of. Some of their parents owned their houses; others rented or still lived in their grandparents’ houses. Some of us spent our spare time studying languages and playing sports; others helped their fathers to fix radios and televisions in their workshops, or kicked a ball around on whatever piece of waste ground they could find.

In the classroom, none of these distinctions meant anything. Some of my best friends (Guidi, for example, who was already an electronics wizard; or Mansilla who was even blacker that Talavera and lived in Ramos Mejía, a suburb so far out of the city that it felt even more remote than Kamchatka) had little or nothing in common with me, and the life I lived. But we all got along.

We all wore a white school smock in the mornings and a grey one in the afternoons, we drank mate at playtime and we jostled and shoved to get our favourite pastry, which the janitor brought in a sky-blue plastic bowl. Our uniforms made us equals, as did our youthful curiosity and energy. Our childlike passions rendered our differences insignificant.

We were equal, too, in our complete ignorance on the subject of Leandro N. Alem, the school patriarch. With his beard and his intimidating scowl, he looked a lot like Melville. Maybe because he was tired of the two-dimensional confines of the painting in the headmaster’s office, he seemed intent on pointing to something just outside the frame. The obvious interpretation might suggest that he was pointing to the future path we would travel. But the nervous expression the painter had given him made it seem more likely that Alem was saying that we were looking in the wrong place; that we should not be looking at him but at something else, some mystery that did not appear in the painting and, being ambiguous, could not be but ominous.

In all the time I spent in these classrooms, nobody ever taught us anything about Leandro Alem. Many years later (by which time I was living in Kamchatka) I discovered that Alem had rebelled against the conservative administration of his time in support of universal suffrage, taken up arms and wound up in prison though he lived to see his ideas finally triumph. Maybe they did not mention Alem to us because they wanted to spare us the inconvenient fact that he had committed suicide. The suicide of a successful man can only cast a pall over his ideas – as it would if St Peter had slit his wrists or Einstein had swallowed poison while living in exile in the US.

So it would be naive to imagine that it was only by chance that I attended the school that bore his name every day for six years – until the morning that I walked out and never went back.

5

A SCIENTIFIC DIGRESSION

That April morning Señorita Barbeito closed the classroom blinds and showed us an educational film. The film, in washed-out colours, with a voice-over dubbed by a Mexican narrator, discussed the mystery of life, explaining that cells came together to form tissue and tissues came together to form organs and organs came together to create organisms, though each was more than the sum of its parts.

I was sitting (to my frustration, as I’ve said) in the front row, my nose almost pressed against the screen. I only paid attention for the first few minutes. I registered the fact that the Earth had been formed in a ball of fire 4,500 million years ago. I remember it took 500 million years for the first rocks to form. I remember it rained for 200 million years – that’s some flood – after which there were oceans. Then, in his deep voice and his thick Mexican accent, the narrator started talking about the evolution of species and I realized he had skipped the bit of the story between the Earth being barren and the first appearance of life. I thought maybe there was a section of the film missing and that this was why the Mexican kept banging on about mystery. By the time I’d finished thinking this and tried to go back to the film I’d lost the thread, so I didn’t understand anything after that.

But this business of the mystery of life stuck with me. I raised some of my questions with mamá, who explained to me about Darwin and Virchow. In 1855 Virchow had proposed that omnis cellula e cellula (‘all cells from cells’), thereby stipulating that life was a chain whose first link, mamá had to admit, was not a trivial matter. It was also mamá who filled in some of the holes in the Mexican narrator’s calendar. She explained that the first single-cell life forms appeared on Earth 3,500 million years ago in the shallow oceans, produced by the longest thunderstorm in history.

Other things I discovered later while I was living in Kamchatka among the volcanic eruptions and the sulphurous vapours. I discovered, for example, that we are made up of the same tiny atoms and molecules as rocks are. (Surely we should last longer.) I discovered that Louis Pasteur, the man who invented vaccinations, conducted experiments that proved that life could not appear spontaneously in an oxygen-rich atmosphere like that of our Earth. (The mystery was getting bigger.) Later, to my relief, I discovered that a number of scientists contend that in the beginning the Earth had no oxygen, or only trace amounts.

Sometimes I think that everything you need to know about life can be found in biology books. They discuss the way that bacteria reacted to the massive injection of oxygen into the Earth’s atmosphere. Until that point (2,000 million years ago, according to my chronology), oxygen was fatal to life. Bacteria survived because oxygen was absorbed by the planet’s metals. When the metals were saturated and could absorb no more, the atmosphere was filled with toxic gas and many species died out. But the bacteria regrouped, developed defence mechanisms and adapted in a way that was as effective as it was brilliant: their metabolism began to require the very substance that, until then, had been poisonous to them. Rather than die of oxygen toxicity, they used oxygen to live. What had killed them became the air that they breathed.

Perhaps this ability that life has to turn things to its advantage doesn’t mean much to you. But let me tell you that, in my world, it has meant a lot.

6

FANTASTIC VOYAGE

Five minutes into the film, I wasn’t thinking about cells or mysteries or molecules at all – I was playing. I discovered that if I looked at the screen and let my eyes go out of focus, the images became 3-D: psychedelia for beginners. After I’d been staring at the little moving circles and bananas of cell tissue for a while, the edges of the screen began to disappear and it was like I’d fallen into magma.

At first it was fun. It was like being in Fantastic Voyage, that film where they shrink a submarine down to microscopic size and inject it into the bloodstream of a human guinea pig. But after a while, I felt dizzy. If I didn’t stop, I was going to throw up my breakfast.

I turned around in my seat, looking for somewhere to rest my tired eyes. In the half-light of the classroom, Mazzocone was eating the sandwich that was supposed to be his lunch, Guidi had fallen asleep and Broitman was playing Six Million Dollar Man with a toy soldier. (Making it run in slow motion and jump like a cricket.) Bertuccio had his back turned to me. True to form, he had leapt to his feet and was telling Señorita Barbeito that he was not about to swallow the idea that once upon a time there was just a single cell in the ocean, then time passed and – boom! – that cell turned into us.

7

ENTER BERTUCCIO

Bertuccio was my best friend. It might sound like bull, but I swear that by the age of ten Bertuccio was reading Anouilh’s Becket and claiming he wanted to be a playwright. I had read Hamlet, because I didn’t want to be outdone, and because we had a copy of it at home (we didn’t have a copy of Becket) and even though I didn’t understand a word of Hamlet, I wrote an adaptation that I planned to perform with my friends in the alcove between the kitchen and the patio, which would make a fantastic stage if mamá moved the washing machine.

But I was only trying to seem grown up; Bertuccio actually wanted to be an artist. He had read somewhere that an artist questions society and ever since he had been questioning everything, from the cost of school fees and the point of wearing a white smock in the morning and a grey one in the afternoons to the veracity of the story about French and Beruti handing out blue and white ribbons to the rebels of the revolution of 1841. (How could they have known that Belgrano would make the Argentine flag blue and white? What were they, psychic?)

Bertuccio was forever embarrassing me. One time we went to the cinema to see Gold, which was over-fourteens only and the guy on the ticket desk asked us for ID. Bertuccio admitted that he was underage but said that he had read the book and hadn’t found anything liable to deprave or corrupt in it and informed the guy that no one had the right to presume that he was too immature to see a movie. When the ticket seller tried to interrupt him, Bertuccio solemnly announced that he, my dear sir, had already read Becket, The Exorcist and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (or parts of it, at least) ‘which is more than many adults can say, or are you calling me a liar?’

Whenever he got me into this kind of mess, I was the one who came up with the solutions. When Bertuccio got tired of talking and the guy on the ticket desk couldn’t stand it any more, we went up the marble staircase to the first floor of the Rivera Indarte Cinema and hid in the toilets, waited until the usher had punched all the tickets for the Pullman seats, then, when he went into the cinema to show a latecomer to his seat, we snuck in behind him and hid behind the curtains. We’d missed the first fifteen minutes, but at least we got to see the film.

Gold was shit. There weren’t even any naked women in it.

8

THE PRINCIPLE OF NECESSITY

On this particular morning, while Bertuccio was challenging Señorita Barbeito over the very foundations of the temple of science, I was looking for a pencil and some paper to play Hangman.

Señorita Barbeito sighed and told Bertuccio that of course there was a principle that explained everything: cell division, cells combining so as to develop complex functions, creatures leaving their aquatic environment, developing colours and fur, seeking new sources of energy, evolving paws, moving about and standing erect. Mazzocone was getting upset now because he realized he would have nothing to eat at lunchtime; a thread of drool was trickling down Guidi’s chin; Broitman was explaining to me that his Action Man cost $6 million and I was thinking how cool it would be to actually throw up and splatter the screen while Señorita Barbeito was explaining to Bertuccio that this principle that explained how an organism develops and adapts to changing circumstances is the principle of necessity.

Bertuccio wanted to stand his ground; he was determined not to let Señorita Barbeito twist his arm on this, so I twisted his arm, literally. He asked what I wanted and I said would he like to play Hangman. He looked as though he was considering the possibility; his philosophical debate could always be resumed later. (I had come up with a word with lots of Ks that I knew would baffle him.) Bertuccio agreed but only if he could have the first go. He marked out an eleven-letter word while I was drawing the gallows. I said ‘A’ and he started filling in the blanks. There were five As in Bertuccio’s word.

‘You’re crazy’, I said.

‘Just wait,’ he said, ‘you’ll see,’ theatrical as ever.

I said ‘E’ and he drew the head.

I said ‘I’ and he drew the neck.

I said ‘O’ and he drew one arm.

I said ‘U’ and he drew the other arm.

This is hard, I thought. An ill-fated ‘S’ earned me the body and after a suicidal ‘T’, I was hanging by a thread.

Then there was a knock at the door and mamá came in.

The only thing I learned from the whole cell business: people change because they have no alternative.

9

THE ROCK

We used to call mamá the Rock. In the Fantastic Four, a Stan Lee comic, one of the Four is this guy made of rocks called ‘The Thing’. That was where we got the idea. Mamá wasn’t exactly thrilled about being compared to some bald, knock-kneed guy, but she was flattered that the name acknowledged her authority. She was happy as long as it was only me and the Midget that used the nickname. When papá called her the Rock – and papá did it more than we did – it was like everything was happening in Sensurround, the effect they use in disaster movies where all the seats shake.