1,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

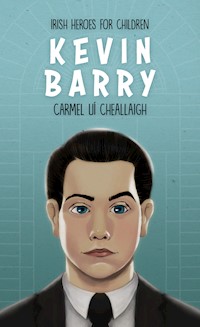

On a dark November morning in 1920, Kevin Barry, head held high, marched to his death in Mountjoy Prison. He was the first and youngest person hanged during the Irish War of Independence. Born the fourth of seven children, the family was split between Dublin and Carlow, after the early death of his father. He loved playing Gaelic football, Hurling and Rugby. A brilliant student, he won a scholarship to study medicine. Kevin also had another life, as a soldier in the Irish Volunteer Army with the sole purpose of obtaining a free independent Ireland. Then his two worlds collided and his part in the Monk's Bakery Ambush sealed his fate. By sticking to his principles and making the ultimate sacrifice, he instigated the move towards a truce that would change the course of Irish history forever. What led this teenager to forego his bright future for the gallows?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

©Carmel Uí Cheallaigh, 2020

Epub ISBN:978 1 78117 746 4

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

To Olivia and Dylan, a new generation of readers.

Prologue

The Ireland that Kevin Barry was born into at the beginning of the twentieth century was a part of the British Empire; it had been so for hundreds of years.

However, a move to revive Irish culture had begun shortly before Kevin’s birth. In 1884, for example, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) had been founded in Co. Tipperary. The aim of the GAA was to preserve and nurture national sports, in particular Gaelic football, hurling and handball. Six years later, in 1892, the Irish National Literary Society was established, encouraging the preservation of Irish customs and literature. The Gaelic League, now Conradh na Gaeilge, followed in 1893, aiming to revive the everyday use of the Gaelic language, as it was felt that speaking and reading in Irish in everyday life was the best way to show that the Irish people were different from the English.

Although the majority of Irish people were Catholics, Protestants were the more powerful, dominant class at this time. But this too was changing. In Dublin businesses, for example, the balance of power was shifting away from Protestants to an expanding group of middle-class Catholics.

The resurgence in all these areas meant that, by 1900, Irish culture was blossoming. In politics, the idea of a free, independent Ireland was also steadily gaining momentum. And during the period of Kevin’s short, eventful life, this momentum was to explode into dramatic, tragic action.

1 Childhood

Kevin Gerard Barry was born at 8 Fleet Street, in the Temple Bar area of Dublin, on 20 January 1902. It was a Monday and, as we will find out, there would be two other significant Mondays in his short life.

Kevin was the fourth of seven children born to Mary and Tom Barry. Most babies were born at home back then and the Barry babies were no exception. Kate Kinsella, who worked as the family’s long-time live-in housekeeper, assisted at the birth. It was normal for women to help at home births at the time, if there were no complications. On the other hand, husbands were not allowed in the room under any circumstances, instead forced to pace up and down outside the bedroom door, eagerly awaiting the good news.

Tom Barry was delighted after Kevin’s birth. He now had a second son to help him with his farm in Carlow and the successful Dublin dairy business that he ran with his sister, Judith. His sons would carry on the Barry surname for generations to come. Tom must have felt that the future looked very bright for all of them.

In line with the Catholic custom of christening babies shortly after birth – infant mortality was high in those days, with one in five babies dying while still very young – Kevin was baptised the next day in St Andrew’s parish church in Westland Row, a short distance from their home. His godparents were his uncle, Jimmy Dowling, and Elizabeth Browne, a neighbour from Carlow. Mr and Mrs Barry were always keen to keep the connection with their native county.

Family records show that the name Kevin had first entered the family in the early 1800s and had been passed down through the generations. The Barry surname is of Norman origin and Kevin’s ancestors came to Ireland in 1170 with the Anglo-Norman invaders. The family originally landed in Cork but, centuries later, fled from that county when the notorious Oliver Cromwell invaded. They kept moving until they finally settled in Tombeagh on the Carlow–Wicklow border.

On Kevin’s mother’s side, the Dowlings too were strong farmers and lived in Drumguin, across the road from the Barry farm. They were a close-knit family unit, and would continue to be throughout Kevin’s life.

***

Kevin had five sisters – Kathleen and Sheila, who were older than him, and Ellen, Mary and Margaret, who were younger. His only brother, Michael, was two years older and his best friend.

All the children attended the Holy Faith Convent in Clarendon Street, which had separate girls’, boys’ and infant schools. The nuns were strict. Giggling in the yard during breaktime was not encouraged. Clapping their hands loudly, the nuns were known to remark, ‘Children, children, Our Lady never laughed.’

Kevin made his First Holy Communion while at the convent and his precious communion medal remains in Tombeagh, in the Barry family home. From a young age, he was proud to serve as an altar boy in St Teresa’s Carmelite Church nearby. Prayer was an important part of family life. Tom, Mary, Aunt Judith and Kate would assemble the children at six o’clock each evening as the Angelus bell rang out. After the Angelus, they always recited a decade of the rosary.

Aunt Judith was an astute businesswoman and from Monday to Friday worked tirelessly in the family’s dairy business, which at the time was a world where there were very few women. Still, determined to prove her worth, she dealt with customers and accounts and all the paperwork. On Saturdays, she loved to relax with her nephews and nieces. If the weather was good they made a picnic and walked to St Stephen’s Green. Sometimes they took one of the newly electrified trams, wittily nicknamed ‘flying snails’, to the Phoenix Park, where they would visit the zoo. If the weather was bad she brought them to one of the recently opened Bewley’s cafés. There she sampled the fine oriental teas on offer, while the children enjoyed the sticky buns. Judith also often took them to the library. All the children adored books and liked to visit the Kevin Street Public Library, which had opened its doors for the first time in 1904.

One Saturday, when Kevin was about two years old and no longer the baby of the family, Judith decided to take him to the Stanley studio in Westmoreland Street to have his photograph taken. This black-and-white photograph stands on the sideboard in the Barry family home in Tombeagh to this day. It portrays his thoughtful little face as he stares at the camera, wearing the toddler fashion of the day: a dark petticoat covered by a white pinafore, boots and stockings, all topped off with a wide-brimmed straw hat from under which his blond fringe peeps out.

Judith was not the only matronly figure in Kevin’s young life. In addition to her other duties, Kate Kinsella watched over the ever-increasing Barry brood. Kate came from a staunch nationalist Ringsend family and, although she could not read or write, she was an excellent storyteller. She recounted tales of the 1798 rebellion, in particular the Battle of Hacketstown in Co. Carlow, a battle that left 300 rebels dead. She told of how the heroic Irish leader of the battle, Michael Dwyer, hid in the Wicklow Mountains for two years afterwards, eluding British soldiers. She taught them rebel songs that she had learned by heart as a child. Strains of ‘The Croppy Boy’, ‘Boolavogue’ and ‘Kelly the Boy from Killane’ emanated from Fleet Street. During these happy sing-song hours, little did the family suspect that Kevin himself would one day be the subject of probably the most famous of all Irish rebel songs. How chillingly accurate and personal those immortal words from ‘Boolavogue’ would become: ‘For Ireland’s freedom we’ll fight or die’.

***

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)