Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

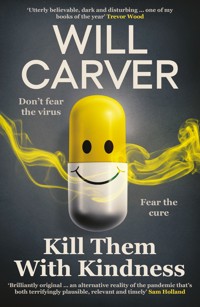

A Japanese scientist thwarts an international plot to release a deadly virus by mutating it to make people kinder, but something goes horribly wrong … A darkly funny, mind-blowing speculative thriller from the 'most original writer in Britain´ (Daily Express)… `Utterly believable, dark and disturbing … one of my books of the year´ Trevor Wood `Brilliantly original … an alternative reality of the pandemic that's both terrifyingly plausible, relevant and timely´ Sam Holland `Clever, compelling, funny and it really makes you think: could it yet happen? Or did it happen already?´ Daily Mail `Idealism clashes with political cynicism in a scathingly pointed satire that serves as a reminder of how the pandemic brought out the best in people but also, in some instances, the very worst´ Financial Times _________ Compassion may be humanity's deadliest weapon… The threat of nuclear war is no longer scary. This is much worse. It's invisible. It works quickly. And it's coming… The scourge has already infected and killed half the population in China and it is heading towards the UK. There is no time to escape. The British government sees no way out other than to distribute 'Dignity Pills' to its citizens: One last night with family or loved ones before going to sleep forever … together. Because the contagion will kill you and the horrifying news footage shows that it will be better to go quietly. Dr Haruto Ikeda, a Japanese scientist working at a Chinese research facility, wants to save the world. He has discovered a way to mutate a virus. Instead of making people sick, instead of causing death, it's going to make them... nice. Instead of attacking the lungs, it will work into the brain and increase the host's ability to feel and show compassion. It will make people kind. Ikeda's quest is thoughtful and noble, and it just might work. Maybe humanity can be saved. Maybe it doesn't have to be the end. But kindness may also be the biggest killer of all… _______ `One of the best things I've ever read … incredibly moving and hugely entertaining´ Chris McDonald `It's the author's black humour and thought-provoking observations on human nature and our society that … take over your brain to the extent that you'll be thinking about it for weeks after´ CultureFly `When Carver switches into full sci-fi, everything that comes before is injected with even deeper and darker themes, adding new layers that make the unpacking of the novel's final conclusion all the more satisfying´ SciFi Now `His best yet. Carver just gets better and better´ S.J. Watson `First and foremost a scathing takedown of government responses to the coronavirus outbreak´ SFX `The final chapters will have you racing through the pages to find out what happens … Carver manages to get the right balance of dark humour, touching moments and razor-sharp social commentary´ Crime Fiction Lover `Arguably the most original writer in Britain´ Daily Express `Insightful, sharp-minded, and fascinating … a brilliant twist on a pandemic´ Sarah Moorhead `Thoughtful, challenging and unafraid to examine the impact huge events can have on the human condition … his most important novel to date´ The Madrid Review `Unflinching, smart and entertaining … as thought-provoking as it is brilliant´ Isabelle Broom `One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction´ Alex North **New Scientist BEST NEW SCIENCE FICTION BOOKS**

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING

THIS ORENDA BOOKS EBOOK!

Join our mailing list now, to get exclusive deals, special offers, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways, and so much more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Click the link again so that we can send you details of what you like to read.

Thanks for reading!

TEAM ORENDA

i

ii

PRAISE FOR KILL THEM WITH KINDNESS

‘Kill Them With Kindness may be one of the best things I’ve ever read. I found it incredibly moving and thought-provoking, as well as hugely entertaining. It’s got the usual Will Carver flair and style; it’s something only he could’ve written, and boy am I glad he did. I don’t think I’ve read anything like it. An incredible accomplishment!’ Chris McDonald

‘Brilliantly original. Kill Them with Kindness is sometimes heartbreaking and poignant, often laugh-out-loud funny. A witty political satire, it shows us an alternative reality of the pandemic that’s both terrifyingly plausible, and relevant and timely’ Sam Holland

‘Insightful, sharp-minded, and fascinating. Carver presents a brilliant twist on a pandemic in a thought-provoking, topsy-turvy world of politics, science and the humans affected. Crazy and brilliant’ Sarah Moorhead

‘It’s his best yet. Carver just gets better and better.’ S.J. Watson

‘An unflinching, smart and entertaining novel that is as thought-provoking as it is brilliant’ Isabelle Broom

‘Thoughtful, challenging and unafraid to examine the impact huge events can have on the human condition. Will Carver’s work is always timely, and this is his most important novel to date’ The Madrid Review

‘Another existential mind warp taking “be kind” to a whole new level. Clever and thought-provoking, always. Beautifully written, always. Intensely addictive, always. Mad as a box of frogs, of course’ Liz Barnsley

PRAISE FOR WILL CARVER

‘Carver is a smart, stylish writer who has created a uniquely scary personality … leaves us entertained and disturbed in equal part’ Daily Mail

‘Cements Carver as one of the most exciting authors in Britain. After this, he’ll have his own cult following’ Daily Express

‘Weirdly page-turning’ Sunday Times iii

‘Laying bare our twenty-first-century weaknesses and dilemmas, Carver has created a highly original state-of-the-nation novel’ Literary Review

‘Arguably the most original crime novel published this year’ Independent

‘At once fantastical and appallingly plausible … this mesmeric novel paints a thought-provoking if depressing picture of modern life’ Guardian

‘Unlike anything else you’ll read this year’ Heat

‘A powerful look into the abyss of a psychopathic personality’ Publishers Weekly

‘Wickedly fun’ Crime Monthly

‘One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction’ Alex North

‘A gripping novel laced with humour and cutting character insight … a thrill from start to finish’ Sarah Pinborough

‘Equally enthralling and appalling … unlike anything I’ve read in a very long while’ James Oswald

‘Creepy and brilliant’ Khurrum Rahman

‘Reminiscent of The Shining … a creeping and perfectly crafted novel tinged with dark humour and malice’ Victoria Selman

‘A masterfully macabre tale’ Louise Mumford

‘Magnificently, compulsively chilling’ Margaret Kirk

‘Fans of Chuck Palahniuk will adore Carver … he is utterly brilliant’ Christopher Hooley

‘Will Carver’s most exciting, original, hilarious and freaky outing yet’ Helen FitzGerald

‘Thrilling and completely original … deserves to become an instant classic’ Kevin Wignall

iv

KILL THEM WITH KINDNESS

WILL CARVER

vi

vii

For those who care more about seeing than being seen.

viii

‘Near the gates and within two cities, there will be two scourges. The likes of which have never been seen. Famine within plague. People put out by steel. Crying to the great immortal God for relief.’

Nostradamus

Live. Laugh. Love.

Anonymous

CONTENTS

THE END2

3

HAIRDRESSERS IN IPSWICH

They’re lining up around the block to collect their dignity pills. A mixture of diazepam, morphine and phenobarbital will eliminate any pain and cause a sleep that eventually falls into a deep coma. The digoxin and amitriptyline will induce cardiac arrest within that coma condition so that death is comfortable.

That’s the best way to go.

Better than any war in the Middle East.

Better than any famine in Africa.

Better than any plague made in China.

The government has allocated sixty-seven million of these pills, for free. One for every person in the country. Old. Young. Sick. Healthy. They have been distributed to every doctors’ surgery in the land. People are queueing in the streets for their own death.

Waiting for their one pill. Their ticket away from this hellish mortal coil. It’s the same pill for women as it is for children, which is the same as it is for men.

It’ll work.

It will be more dignified than the bleeding and blisters and gagging and choking that has been shown on the TV screens and shared across social-media channels. China no longer has the largest population on the planet, they say.

This is the end. Every country with nuclear weapons could wipe themselves out, but that’s not as kind as the dignity pill. Some arsehole marketing guru gave up that gem of a name to take some of the edge off global euthanasia.

It’s not the suicide pill, it’s the comfort pill.

Nobody wants to give their kid a ‘top-yourself tablet’ or a ‘coma capsule’. Much better that they take their ‘composure pastille’ or their ‘integrity lozenge’. Pepsi are running a campaign getting people to swallow it down with their drink. Still making millions as the world implodes.

There’s a pill set aside for the prime minister and one for Doris who 4works at the Job Centre in Macclesfield. The queen has one if she doesn’t think the bunker will hold. Librarians in Telford don’t have a bunker. Neither do teachers in Yeovil or hairdressers in Ipswich.

The government suddenly seems to care about the homeless situation and has called on volunteers to deliver blister packs to as many cardboard jungles as possible.

Every class, race and sexual orientation has an equal right to end their own life before the plague sweeps in from across the ocean. Nobody should suffer. It may be the end of the world, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be a pleasant experience.

This world. Where countries face growing health issues because they are eating too much while others die of starvation. Where man thought the best way to stop all wars was to build the biggest bomb. Where every one of the seven hundred gods is unresponsive to the prayers of their worshippers. Where religious disagreements go back so far that nobody knows what they’re fighting for now. Where restaurants deplete the seas to feed people who no longer talk to one another at dinner.

The pill is the only answer.

It is too late to fight. To save.

The horsemen have arrived.

War. Famine. Pestilence. Death.

The only thing left is to give up.

And all people had to do was find some genuine compassion. All they had to do was be kind. And mean it. And maintain it.

STAY AT HOME

It was only a month ago that the first test was carried out. It was a Sunday night, around the time when most people are starting to dread the fact that their weekend is over and they have to go into the office the next day. The same time that many people are flicking through the channels on their televisions, frustrated that there’s 5nothing on, and finding themselves watching Antiques Roadshow for the twentieth week in a row.

If ever there was a litmus test for the kindness of humanity, it is Antiques Roadshow. You can judge the mental state of the collective consciousness by comparing the percentage of people who want an item to be worth a lot of money against those who hope dear old Gladys from Wolverhampton hasn’t noticed that the R on the Rolex watch passed down through generations is, actually, a B. And it’s worth nothing.

But you also can’t blame people for being a little cantankerous on a Sunday evening, when there’s nothing else on TV and they have to return to the call centre in twelve hours.

It was one of those nights. Kenneth Hargreaves, a war veteran, had brought in a jewel flower to be appraised. The expert was examining the piece, floating the possibility that it was a botanical study by Fabergé. If so, it might be worth seven figures.

That’s when the alarm sounded.

The first test.

Millions of mobile phones across the country suddenly started blaring a siren noise. Some people were waiting eagerly by their phones to see what would happen, others were startled, having forgotten it was scheduled. Many missed the expert’s final appraisal as they waited for the piercing tone to desist.

The idea behind the test is that the government has the ability to warn people en masse about dangerous incidents. Local flooding, for example. But also things like terrorist attacks. When an unexplained World War II bomb was discovered in a garden in Plymouth, the alert was used to inform local people to evacuate the area until the possible threat had been neutralised.

If an enemy state launches a nuclear bomb at the UK, the alert will tell people to flee the target area or say goodbye to their loved ones. If Mother Nature decides she has had enough of us polluting the planet and sends a five-hundred-foot tsunami, the alarm will sound, telling coastal townsfolk to seek higher ground.

Of course, there are so many things to think about with blanket 6campaigns like this. What about people in abusive relationships who hide secret phones that they don’t want their partners to see? What if they start sounding and are discovered? What level of abuse could follow such a revelation?

So the government had to release instructions on how to disarm the warning:

Go to ‘Settings’. Find ‘Emergency Alerts’. Turn off ‘Severe Alerts’ and ‘Extreme Alerts’.

Everyone in the country needs to have the alert on because they are days away from the arrival of this biohazard. This gas. These insects. Whatever it is that is ravaging its way across the sea to wipe out civilisation. If the wind doesn’t take it in a different direction, if the military don’t find a way to stop it, the people need to know when to take their pills.

Of course, there will always be a small percentage of people who don’t like to do as they are told, who are happy to take their chances at surviving. And there are some who simply choose not to believe.

They’ve been lied to before.

They were told to keep their distance.

They were told to stay at home.

They were told to get vaccinated.

And they don’t want to be told when to kill themselves.

So they turn off the alert and they don’t collect their pill and they know just how much that Fabergé flower is worth.

THE LIFEJACKET PROTOCOL

It’s Wednesday. The world ends tomorrow.

On a Thursday.

Who thought that was a good idea?

The weather guy on the BBC points at part of the country and tells everyone that it’s raining there. It’s raining everywhere. That it’s colder up north. He waves an arm and says something about a cold 7front and pollen levels and pollution around the bigger cities. And then he points at some yellow, blurred blob below Svalbard, over the Barents Sea, and says that it’s moving towards us. That it should arrive by dinnertime tomorrow.

It’s all very British.

He doesn’t say that everyone will be dead, he just lets people know that there is an opportunity for a last supper. Maybe the kids can have dessert first. Maybe the vegans can gorge on foie gras. Maybe forget the food, and drink so much champagne that you won’t need the dignity pill.

There is no mention that it will be his last weather broadcast, but it is. He had been working in Acton for years until the studio relocated to Salford. His mother, sister and two nephews live in Dorset. They are planning to spend the day together. They’re not doing anything in particular, just staying in the house. Talking. Cooking. Letting the kids play in the garden.

Maybe they will stay up all night and reminisce. Maybe they will imagine what the world could have been if they had believed the scientists or tried harder to listen or been more present for other people.

The plan is to live, love, possibly even laugh. Just like the canvas on the hallway wall says to do.

Others will choose to loot. The entitlement that got us here in the first place will remain until the bitter end. They will steal cars they could never have afforded and drive them at speeds that will no longer get them arrested because the police are off duty.

The end of the world can act like a purge. There will be murder and rape just because someone wonders what that will feel like. And they’re going to die anyway. On a goddamned Thursday.

The alarm will sound on their mobile phones. If they have small children, they have to administer their pills first, like the lifejacket protocol on a crash-landing plane. Because they shouldn’t have to see their parents die and then be devastated by the ensuing plague. Even if they’re going to die either way.

Some parents will panic and forget. Some children will have to be 8brave enough to do things themselves. And others will have to see it out. Because they won’t be able to take the pill. They shouldn’t have to. They’re kids. It’s not their fault. They were brought into this world and left in front of their screens. And their idols were brainless. And their teachers were overwrought. And their health service was strained. And their leaders morally bankrupt.

Somehow, they have lost the ability to fight for themselves. Resilience is all but extinct. Kids are fragile, and parents are scared of upsetting them.

Maybe it’s better this way.

Start over again.

On Friday.

A MIDNIGHT APERITIF

The alarm sounds just after seven. A little later than was originally anticipated. The Met Office staying true until the end by not predicting things quite right. Many hoped the poison would blow right past and not hit land until Florida, where most of the residents are already dead in some way.

One hour until impact. Prepare your families. May God be with you.

That’s all it says. The extreme alert sounds more like bidding someone an interesting cruise.

In Croydon, a new mother cries as she crushes one of the pills into a powder to add to her baby’s milk. She looks into her child’s eyes as they guzzle the warm formula. Oblivious and innocent. And trusting. She and her husband had tried so long to have a baby. He has already taken his pill. Couldn’t stand the pressure. He was anxious. Didn’t want to see his family perish so went peacefully and selfishly in his reading chair after lunch.

In Oxford, eight students have been drinking since breakfast. They have taken their pills and have paired off for one final moment of intimacy. What a way to go. 9

Families barbecue on the beach in Cornwall and dance until the drugs kick in. They can die on the sand and be collected by the high tide. There will be nobody around to bury them, anyway.

Many churches and temples and mosques are filled with parishioners who still believe in God’s great plan. They are expecting a last-minute rapture or they have just given in to His will. They are some of the least scared. Many are almost excited about their next chapter. What is it they have been fighting about all this time?

Not everyone is so calm and stiff-upper-lip about it. There are people who have measured the area of the encroaching gas, or whatever it is, and figure that, if they get in their boat and go south of the Isle of Wight, they will be out of harm’s way. They can come back and claim the land as their own. Rebuild the country that once dominated the globe.

The über-rich have fuelled whatever vehicles they have to get out of there. The airports might be shut down, but the runways are still there. Private jets are still there. There’s no control tower so it might be a case of Russian oligarchs flying into each other and exploding, but they are going to die, anyway.

The helicopter on the roof that was once a status symbol, an attempt at peacocking, now seems to have some practical application. Hover above the gas. Witness the destruction and chaos. Slowly lower back to the roof in time for a midnight aperitif.

It’s moving in. And it’s not going to stop.

Still, despite the warnings from the government and the military and the scientists, and the photographs and videos of the devastation in China, there are people who don’t believe it. Who call it fake news. Who create conspiracies about nanotechnology and propaganda. They don’t think we went to the moon in ’69. They say Lee Harvey Oswald was a patsy. And they are so convinced, they didn’t queue around the block for their dignity pills.

Because they see no dignity in killing themselves for something that is not their fault. Their ideas might not fall in line with the 10majority, but they have their own faith. They think it is always right to question rather than following blindly.

And they don’t all get together. They are mostly alone. Dotted around the country. Risking their skin flaking away and their eyes being eaten out of their sockets and throwing up until they can no longer breathe.

There’s a refined chaos in that final hour. People realise that, in death, they finally have the ability to make their own choice about their fate. And they realise this because they are selfish and self-absorbed and solipsistic. Because, if their realisation was that there was a world beyond themselves, that kindness, compassion and considered thought was a superpower, that benevolence and generosity was a gift, they wouldn’t be lying in a coma, in bed with their children, not noticing that they are already dead from a heart attack.

That nobody had to die.

THE FIRSTSCOURGE

ONE YEAR EARLIER…

13

THERE IS MOULD IN THE PETRI DISH

Knowledge, research and experimentation are huge parts of scientific discovery, of course, but blind luck and chance have been responsible for some of the greatest finds in the history of medicine.

Edward Jenner, developer of the first vaccine, stumbled upon a cure for smallpox. Speaking with a milkmaid who had contracted the irritating, though not deadly, cowpox – a hazard of the job – she remarked that people who had cowpox never seemed to get smallpox.

Jenner injected a young boy with cowpox from the sores on the milkmaid’s hands. A small dose. He grew feverish but was otherwise healthy. Weeks later, he injected the same boy with a small dose of smallpox, a deadly disease causing many fatalities. The boy did not contract smallpox.

Vaccinations were born.

Of course, the method was unethical, but progress was made that saved millions of lives.

Without the misfortune of Fleming, the idea of antibiotics, which are so readily available and relied upon now, may have taken much longer to discover and develop.

A petri dish of staphylococcus bacteria, which Fleming was studying, became contaminated, growing mould inside. Instead of throwing the sample away, Fleming examined it, noticing that the areas around the mould were clear. This showed that it was lethal to the bacteria. He had discovered penicillin. Still a vital antibiotic to this day.

Dr Haruto Ikeda is about to have such an accident.

A discovery that could change the world.

He has a special mind when it comes to virology, but he struggles with things like emails and syncing his calendars. Apart from Candy Crush, his favourite app on his phone is Messages. He can write documents easily enough and he is something of a natural with a spreadsheet. But he can never find the files he wants when he needs them.

He hits save and then doesn’t know where they go. 14

It is late in the lab. He has cleaned and sterilised the space he has been working in today. Somebody, recently, helped him figure out how to monitor the mice he experiments on through his mobile phone. It took some getting used to, and he didn’t really want a fifth app clogging up his home screen but it is part of his job and his study, so he pushed past it.

In his office, at his desk, he scrolls through one of the drives, looking for a spreadsheet that he was only using this morning.

Why does it not just save everything to the same place? he asks himself.

He clicks one folder and it’s not there.

He tries three others that all have names that are too similar to be useful.

Ikeda has the highest level of access in the building. His key card will get him through any door and his computer login will get him into any folder, which is the opposite of what he really needs.

He eventually finds a folder that looks as though it could be the right one and opens up the spreadsheet inside. It is not the one he is looking for but it is no less interesting. The doctor sighs, at first, then his eyes narrow as he moves closer to the screen.

It’s not his file.

But it is his work.

There are references to his discoveries concerning the SARS-CoV-2 virus that was found in the cave. There are mentions of the experimental mutation that would have proved so deadly it had to be steamed out of all existence. There are notes that seem to have been taken verbatim from his own musings. And theories that he only posed to himself.

One word sticks out.

Tau.

The Greek letter assigned to the variant of the virus Ikeda and his small team have been working with. The one that was found in the cave. The one they are testing and trying to develop a vaccine for, even though it is not known by anyone outside of the Wuxi Institute. 15

And there are dates:

When the Tau virus was discovered.

When it was mutated – into something the scientists referred to as Ypsilon.

When that mutation was eradicated.

The original virus is called Tau by a handful of people in the world who have knowledge of its existence.

That makes sense. It’s all true. Ikeda has a similar list on the file he made that is hiding in some other folder in the cloud.

There’s a future date that says the Tau vaccine is ready. Ikeda assumes this is some kind of deadline that he has not been made aware of yet. It’s not uncommon – there is a lot of US funding, and they love a deadline.

Then another date, just over a year from now:

First Tau infections.

This makes no sense, at first. The virus is aggressive but it is contained. It is isolated within the labs.

Then a date a few months on from that:

Phase one – vaccine rollout.

He contemplates what he is seeing.

It hasn’t clicked yet, but this is serendipitous.

There is mould in the petri dish.

It’s a timeline of events that are yet to occur.

Most people would shut down a file upon realising that they had not created it, but Haruto Ikeda spends a great deal of his time, each day, extrapolating data. It is something he has to be good at otherwise everything would take twice as long. And he is a stickler for detail.

Everything in the spreadsheet seems correct apart from the dates, and that makes it seem purposeful. Working in scientific research is rewarding, at first, but the presence and power of the large pharmaceutical companies can leave even the greatest idealist a little jaded.

He scans the document again. 16

Scientific vocabulary. Calculations. And those dates.

One is the proposed deadline for the vaccine, though it is surely a guide, because these things cannot be rushed, they must be tested and retested and tested again.

Then it comes.

The virus is to be released once the vaccine is ready.

Both have a date.

Ikeda’s mind does not work in a politically strategic way. He cannot understand the motive behind such a thing. He assumes that large amounts of money are probably involved. He has seen the effects of this virus. It is highly contagious and fast-acting.

This is not the same as accidentally discovering the effects of insulin or fortuitously creating the X-ray. But Dr Haruto Ikeda has, through his own technological inadequacies, uncovered a potential plan that could cause a global catastrophe.

But blind luck steps in and shows that information to the one man who can stop it. The one man with the knowledge and experience to save millions of lives.

He doesn’t want to make any changes to the file and he knows that he will never find it again, but the search window on his screen shows the trail of folders he clicked to get to where he is now.

He copies it down onto a Post-it note, so that he can come back to the correct folder, if he needs to. And he sticks that note inside a Lonely Planet Guide for London – somewhere his wife would like to spend some time one day.

The deadline is real.

Somebody wants to release this virus.

They want to infect innocent people for months.

And then they want to vaccinate them against it.

But why?

There is no time for Ikeda to sit and cry at the futility of existence and the dishonour of man.

The situation may call for him to do something unethical for the first time in his illustrious career. 17

Sometimes, progress can only be made by subjecting somebody to a deadly disease.

It is a complicated discovery but, to Haruto Ikeda, there are two solutions, both of which are simple. He could spend the next year testing and developing a vaccine that will eventually save millions from this deadly virus. That’s what he does, and he is great at it.

But there is that second option. One in which he releases his own virus. A more effective virus. In fact, he could release a virus that will make people better. 18

FOURTEEN WEEKSTO PLANNED RELEASE…20

21

A WORLD IN WHICH THEY ARE STARS

Nobody is watching them. And nobody cares.

This is the great misconception under which today’s youth labour: they think everybody is looking at them. They are constantly online, uploading images of themselves or videos where they dance or kick a ball or cook a pie. Or whatever.

And there’s that small hit of dopamine every time they are notified of a like. And they are watching everybody else’s videos and comparing themselves and scouring the comments sections and double-tapping their hearts (and minds) away.

So, they think that everybody is watching them.

But, of course, they are not. They are only interested in themselves. In their own little world that they have created with their own online personas.

Haruto Ikeda worries about the younger generation. He is watching them, for science. Nobody else seems to care.

Yet he notices that teenagers are suddenly more anxious about going out shopping with their parents in case somebody they know sees them. They don’t want to get a part-time job in the town where they live because they could be spotted.

And many parents don’t understand these new pressures because, when they were the same age, they had to go to school even though the idea of putting their hand up in class brought them out in hives. They didn’t know what anxiety was. Nobody in their school year was coming out as gay or trans. Gender fluid was something that was produced when you had sex.

Things have progressed in that sense. There is greater understanding and more tolerance. That’s a good thing. It’s not the issue. Not for Haruto Ikeda.

The issue is one of misplaced power, disillusionment and the loss of self.

The current batch of teenagers are being told that they can be whatever and whomever they want to be, but they are not being 22provided with the tools to make that a sustainable reality. They have been empowered but they still require a guiding hand. They’re still kids. They’re still learning.

But the technology that was supposed to liberate them is preventing their parents from providing that guidance. It’s making these kids believe they are the stars of their own reality show. They think that people are interested in their chia-seed breakfasts and buddha-bowl lunches. They think they can make money from recording make-up tutorials or pool-table trick shots. They have created a world in which they are the stars, they are the centre of their own universes.

So, of course they think that people are watching them and judging them for going shoe shopping with their mother or bowling with their father. It’s no wonder they are anxious and embarrassed about being spotted behind the till at the local supermarket.

But that isn’t the issue, either.

Not to Dr Haruto Ikeda.

It’s that, through the social-media boom, there seems to have been a systematic removal of compassion.

A million people, every day, post something like ‘Be someone’s sunshine when the skies are grey’, and another million people hit like, even though the sentiment is utterly saccharine and disingenuous.

Others push the schmaltz to a Hallmark-card level. ‘Kindness is a passport that opens doors and fashions friends. It softens hearts and moulds relationships that can last a lifetime.’ The message is one of positivity but it’s still too sickly to get behind.

Even when something appears more thought-out – ‘Unexpected kindness is the most powerful, least costly, and most underrated agent of human change’ – it is disregarded. People put it out there because it makes absolute sense – it’s so true – but they do not act in this way. It’s too difficult. And, if nobody else is doing it, somebody is going to stick out. Someone is definitely going to be seen.

It is like Gandhi said: ‘I like your Christ, but I do not like Christians, for they are not like your Christ.’ Posting an inspirational 23quote about kindness on a social-media platform does not make a person kind. It makes them unoriginal.

The people talking about kindness are, most often, not kind.

Kindness requires action.

But something else that Dr Ikeda has discovered through his research over the past few years is that humanity triumphs in the face of adversity. We deal with horror in a way that brings out the best in us – for a short time, at least.

So, in fourteen weeks, when a contagion is scheduled to be released – a contagion that will spread through Wuxi, killing thousands, before being allowed onto aircrafts to be transported around the world, forcing countries to shut down and close their borders. When hospitals are overrun. When people are struggling to breathe. When everybody knows somebody who has died.

Will humanity, once again, step up?

And will it be worth the loss of all those lives?

Could catastrophe get the world back on track?

This is something that Haruto Ikeda contemplates. He has been thinking about it for almost a year. And, because he is so focussed on everybody else, it doesn’t even enter his mind that he is the one being watched.

A POTENTIALLY DEVASTATING BIOWEAPON

When faced with the spread of any coronavirus and with possible pandemic-levels of infection similar to those previously seen with SARS, which reached every corner of the globe, touching millions and killing hundreds of thousands, the person to turn to would be Dr Haruto Ikeda. The world’s foremost expert in this area.

He would know what to do.

How to contain it.

He would be able to develop the first test in his lab.

Ikeda studied virology at Hokkaido University in the early 24nineties, where he developed a fascination with animal coronaviruses and how they can become true human diseases with a high likelihood of sparking epidemics. This was not part of the syllabus, but Ikeda was drawn to it.

By his mid-thirties, Ikeda had risen to a senior position at Kyushu University, an establishment that receives billions of yen in funding for medical research each year. There, Ikeda studied the evolution of viruses. He worked with pig farmers who had developed encephalitis and camel racers who were affected by MERS. His research even suggests that the common cold may have originated in camels.

But it was not until he focussed his attention on animal coronaviruses in bats that his findings would set him apart from anyone else researching in this area.

And this would take him to China.

Specifically to the Wuxi Institute of Virology. A foundation backed by US money. Dr Ikeda spent his first three years investigating viruses similar to SARS found in bats located at a mine in South China. Several of the mine workers had died due to respiratory problems. This was, of course, kept quiet.

The American funding allowed further investigation and experimentation, but it was the work of British scientist, Raymond Task, that provided the researchers with the means of testing the effects of the viruses they were discovering, or indeed creating. Task’s innovation was to inject albino mice with genes that would allow them to develop vascular systems that were similar to humans’. Viruses similar to SARS could then be injected into the mice’s nostrils, and the effects monitored.

Ikeda did exactly that with a cocktail of the virus that had been found in the South China mine. Eighty percent of the mice died.

He realised the implications of his research. That, while the focus of his experiments was to gain an understanding of these types of viruses and eventually develop a universal vaccine against them, there was always the possibility that his findings could be obscured, and used to produce a potentially devastating bioweapon that could be 25targeted towards humans or food crops and result in dire consequences for civilisation.

This epiphany altered the doctor. He became more contemplative. More insular. More secretive. His work continued, but he was momentarily disillusioned. He wanted his work to make a difference for good, for positive change. He looked to Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism for solace. He read the philosophies of Laozi, particularly his thoughts on compassion. That the more we care for others, the greater our sense of personal wellbeing.

That was three years ago. In fourteen weeks, a new coronavirus will be leaked: first, to the population in Wuxi, from where it will spread across the world. And it will happen with or without the backing of Dr Haruto Ikeda, and whether he knows about it or not.

Today he is short-staffed because three of his scientists are seriously ill and off work. One of them has a vulnerable parent who has also been taken sick. The doctor has ordered everybody in the lab to wear a mask that covers their nose and mouth for the entirety of their day at work.

And they listen.

Because with the spread of any coronavirus pandemic, the person to call on for answers would be Dr Haruto Ikeda. Especially as the virus has probably been created in his laboratory.

THE MAN IN THE PERFECTLY PRESSED SUIT

The kids are wrong. They are not being watched. Nobody cares about the dance routine they have learned or what skin care product has given them that glow. But, if you show any indication that you are going to go against the laws and policies of your country, if you intend to attack or even think about harming citizens, somebody will be listening. Somebody will be watching.

In China, there are a lot of people to listen to, which is why 26information needs to be contained. So that misinformation may be monitored.

The ECHELON spy system picks up certain words in phone conversations or text messages or email communications. Certain phrases get flagged as potential threats. Every country has them. These are monitored by the various intelligence agencies around the globe.

You don’t have to email the word ‘Jihad’ or call a friend talking in a code that the NSA laughs at because it’s so easy to crack; you could be marked for buying three components of a nail bomb on Amazon.

You could type ‘assassinate’ or ‘UFO’ or ‘Supreme Assembly of the Islamic Revolution in Iraq’ and it will be gathered by ECHELON. But the same is true if you write ‘steak knife’ or ‘Goldman’ or ‘Harvard’.

And there are private-security firms who operate on behalf of the government but also outside it. Most of them specialise. And they are well funded. It is prudent to ensure that these private companies are employed on a retainer to observe companies involved in major technological advances and it would certainly be wise to listen in and look over any facility researching viruses that could be harnessed and used as a bioweapon.

Haruto Ikeda has been monitored on several occasions. So has his wife. And Dr Bauer. And Zhu Jian, the minister for science and technology. And the billionaire Waylon Taggart. And Ikeda’s college friend and nanotechnology expert, Xiang Lao. And, of course, the British prime minister, Harris Jackson. But, for now, the man in the perfectly pressed suit with the immaculate hair and porcelain skin is merely watching with interest. He does not become a danger to anyone until somebody on that list steps over the line.

HIGH CHANCE OF AN OUTBREAK

Stefan Bauer’s father is dead. The old man had struggled with asthma since he was a kid. Stefan had left the Wuxi Institute of 27Virology with a dry cough and high temperature two days ago. The same as the other two scientists on Ikeda’s team. The kind of symptoms that are difficult for a mutated albino mouse to describe.

Stefan’s father was old but fit. He walked every day. He tried to stay active. The exercise gave him time to think about his wife, who had died a few years before – she had paid a man to paint her bedroom wardrobes and the idiot painted one of the doors shut. When Mrs Bauer forced it open, the door hit her hard in the ribs and caused her to fall. She contracted pneumonia in the hospital and didn’t last the week.

Mr Bauer seemed healthy, but there were underlying conditions that meant a visit to his ailing, highly contagious son, who had been accidentally infected with the Tau virus, proved to be the final attack on the old man’s respiratory system.

Stefan is still struggling with his illness and now has the grief of his orphanhood to keep him company when he comes around from his feverish bouts of sleep.

Dr Ikeda had warned of this. He knew of over thirty labs working with these kinds of viruses. He had told his superiors that, one day, there was a high chance of an outbreak somewhere, that something would eventually escape.

It was inevitable.

Even with the strictest safety and sterilisation procedures, things can leak. It’s been less than a year since Ikeda found that file that alerted him to a possible deliberate outbreak. This time it was an accident, but people are sick and now somebody has died. And it’s worse because Ikeda’s team is so close to a Tau vaccine.

Whoever made that file is not looking for Ikeda and his team to develop a universal vaccine; they want a new kind of weapon and they want an antidote to be developed alongside the disease. It’s not a new idea. The business of pharmaceuticals is so broken and corrupt, it makes the World Boxing Organisation look like a church fête tombola stand run by nuns.

Bauer calls Ikeda to update him on his illness and inform him of 28his father’s passing. ‘We’re screwing around with nature,’ he says. The Tau virus was contained deep within that cave. There was no need to disturb it. But part of Wuxi Institute’s job is to discover potential threats and create vaccines against them, should they ever find their way into the world naturally.

Ikeda doesn’t want to lose Bauer from his team. He’s pragmatic and meticulous and thoughtful beyond the chemistry and biology of what they do every day. Ikeda sees himself in the young scientist – sees that he is exhibiting the same questions and disillusionment that Ikeda suffered years ago.

‘Stefan, I struggle with the same thing, both ethically and philosophically. But this is going to be examined in one of the labs, so our focus has to be on vaccination. There is always a risk of exposure with our work.’ It’s a risk for Ikeda to talk this way, particularly over a telephone line that could easily be monitored. It’s not a secret that Ikeda has been more insular in recent years. Everybody can tell he is different, but he still functions and he gets the work done and the people above him are satisfied with his progress and results.

‘I hear you have everyone in face masks,’ Bauer laughs.

‘How did you hear of that?’ If trivial information is seeping from the building, Ikeda worries about what else is getting out.

‘Jensen sent a text to see how I was doing. I asked her how things were without me and she told me about the masks. Go easy on her, it’s not like she was sharing state secrets.’ Bauer coughs. When he comes back to the phone to say something else, he coughs again, and can’t stop for the next twenty seconds. It sounds painful. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘Stefan,’ Ikeda interrupts, ‘I’m terribly sorry to hear the news about your father. Please take the rest of the week off, you sound awful and you need time to process what has just happened.’

There’s a silence.

Stefan starts to cry.

Then he starts to cough again.

It goes on for almost a minute, and Ikeda hangs up. 29

He returns to his work. Looking into a microscope, he sees the virus – yellow irregular circles with green spikes around the outside that give the coronavirus its name. Corona. A crown. The king of all infections.

Royalty among cruel, harmful influences.

But this is not the same thing that took Bauer and two of his colleagues out of action. It’s not the thing that killed Bauer’s father. This is new. It has nothing to do with the vaccine. It’s a new mutation of the Tau virus.

This is Ikeda’s.

He is calling it CompX. But that is not being recorded on any computer. It is only in Ikeda’s head. And, if he can get it right, it could be the cure.

He moves across his station, captures one of the white, modified mice, and injects into its nostril. He does this another seven times.

And then he waits.

There is a knock at Bauer’s door. He’s not expecting anyone. He doesn’t have anyone anymore. And that’s perfect. He’s alone. He has had everyone taken from him. He is questioning his place in the world. But he is also college educated. He has a degree and some expertise in both chemistry and biology. It also helps that he speaks more than one language fluently. He fits the profile perfectly.

MAYBE IT WAS FATE

Both his parents died when he was nine years old. His father had been drinking and thought it would be okay to get behind the wheel and drive home. It wasn’t such an issue back then. Nor was wearing a seatbelt.

It wasn’t that far to the house.

They would hardly be on the road.

It turns out that he was right – he was a little over the limit but not enough to impair his judgement. He talked with his wife about 30the party, and she placed her right hand on his hand until he had to change gear, then she moved it to his leg. Just as she always did, whether he had been drinking or not.

And when the driver who had been drinking way too much hit their car at speed, she didn’t even have time to try to hold on to her husband before she was thrown through the windscreen.

It was a mess. Glass everywhere. Blood. Smoke. Steam. She was dead. He was hurt. The drunkest driver was screaming for help. He had recklessly endangered anyone in his way that evening, he had killed Harris Jackson’s young mother, and he had the audacity to call for help.

The only person around was Jackson Senior, who could see the mangled, twisted body of the woman he loved. He was not going to help.

A ball of rage and confusion and blame and guilt, the pain in his legs and chest disappeared as he got out of that car and strode over to the struggling drunk murderer.

Jackson Senior yanked the door open to find the whisky-soused wife-killer writhing around beneath his seatbelt, which had somehow managed to sever an arm and then get stuck. Jackson Senior didn’t want this scum to survive, but if he did, he was not going to feel whole again. Jackson Senior took the hand of the arm that was no longer attached, pulled it out of the footwell, ran towards the edge of the bridge and hurled the limb thirty metres down the River Thames.

It made him laugh.

It was an odd time to do such a thing, with his wife contorted on the road behind him. He knelt beside her until the ambulance and police arrived at the scene.

The paramedics loaded the drunk, one-armed man into the ambulance. He was screaming, ‘That fucking psycho threw my arm off the bridge.’

The policeman approached Jackson Senior. ‘Sir, is what he’s saying true?’ 31

‘You think I threw some stranger’s arm off the bridge? Some drunk driver who hit my car head on and killed the love of my life? I think he’s so drunk, he’s forgotten that he only has one arm, don’t you?’

There’s a long pause while the policeman fully digests the situation.

‘You know … I think you could be on to something. I mean, when I arrived, he definitely only had one arm, so maybe it was always like that, I don’t know.’ He wants to smile or wink, but it’s not appropriate. He says it with his face, though. ‘Look, I’m going to need to take some details from you now, but we can get a full statement tomorrow. You got kids?’

‘A son. He’s nine.’

‘You’ll need to go home to him tonight. Come down the station tomorrow. Okay?’

Jackson Senior nods. He obliges the police officer and gives him all the information he needs. More officials turn up. They cordon off the area, they take pictures and they bag Mrs Jackson and take her away.

‘I can take you home,’ the police officer assures Jackson Senior.

‘You know, it’s just up there,’ he points, ‘we almost made it back. A minute either side and she’d still be here.’

The police officer doesn’t know what to say.

‘It’s fine. I’ll be fine. I can walk.’

And he does.

Jackson Senior walks all the way back to his house. It takes him around twenty minutes. They could have walked from the party. They should have. Maybe the drunk driver would have ploughed them down on the pavement. Maybe it was fate.

He lies to the babysitter about his wife and says that she will be coming along shortly after. He doesn’t ask how his son is, whether he behaved. He doesn’t even go up to see the boy. He tells the young girl – the daughter of a friend – that he needs to go into the study to fetch some cash to pay her. He says he is very grateful for her help. 32

She waits in the hallway.

Jackson Senior goes into his study, walks around the back of his desk, opens the top drawer, where he keeps a cheque book and some cash, takes out his hand gun, places it against his temple and pulls the trigger.

The sound startles the babysitter and wakes up his son.

Harris Jackson’s parents died in tragic circumstances. He could have become Batman. Instead, he went the other way, towards something darker, and became the country’s prime minister.

HIDDEN BY THE APPARENT CHAOS

Two days later, Bauer’s father is not the only thing that has died. Four of Ikeda’s mice have perished. Those are not great odds of survival but they are better than they have been.

Ikeda knows he is not quite there yet – the virus is scheduled for release and the vaccine can’t be too far behind. The pressure is on. He feels the weight of his responsibility to save people.

Fifty-percent survival is not good enough, but to Ikeda, it is not the dead mice that concern him, it is the behaviour of the mice that survived that are of interest. Scientifically, of course, but also zoologically. He can see that not only have they survived, their behaviours have also altered. He can’t quite ascertain what is so different, but he will monitor them while performing tests on another batch of innocent rodents.

He leaves a camera running on the cage and lets himself out of the sterile lab to return to his office.

It is a stark contrast to the clean, straight-lined, seal guarantee of the testing area. Ikeda’s office is a mess. The bookshelf behind his desk is filled with the many medical books he has had to read through his training and subsequent career. A framed PhD certificate hangs wonkily on an adjacent wall with reams of medical journals and psychology texts piled on the floor beneath, creeping higher and higher. 33

The bin next to his desk is overflowing with crumpled pieces of paper and prepared-sandwich packets. Ikeda never makes his own lunch. There are clothes on a chair in the corner. A tracksuit, neatly folded on top for when he feels like going out for a run to clear his mind, and a smart jacket hung over the back that he hasn’t worn since the last time somebody important came to the institute.