Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: The Beresford

- Sprache: Englisch

Hotel Beresford: a grand old building, just outside the city, where any soul is welcome, and strange goings-on mask explosive, deadly secrets. A chilling, darkly funny sequel to Will Carver`s bestselling The Beresford… `Superbly paced and remarkably inventive, a book that demands to be read in a single sitting´ M.W. Craven `Delightfully dark and wickedly inventive … with characters that stick around long after the final page is turned, whether you want them to or not´ S J Watson `Multi-layered and masterfully written, this darkly humorous tale will both shock and entertain´ Heat magazine Book of the Month ______________ There are worse places than hell… Hotel Beresford is a grand, old building, just outside the city. And any soul is welcome. Danielle Ortega works nights, singing at whatever dive bar will offer her a gig. She gets by, keeping to herself. Sam Walker gambles and drinks, and can`t keep his hands to himself. Now he`s tied up in a shoe closet with a dent in his head that matches Danielle`s broken ashtray. The man in 731 has been dead for two days and his dog has not stopped barking. Two doors down, the couple who always smokes on the window ledge will mysteriously fall. Upstairs, in the penthouse, Mr Balliol sees it all. He can peer into every crevice of every floor of the hotel from his screen-filled suite. He witnesses humanity and inhumanity in all its forms: loneliness, passion and desperation in equal measure. All the ingredients he needs to make a deal. When Danielle returns home one night to find Sam gone, a series of sinister events begins to unfold. But strange things often occur at Hotel Beresford, and many are only a distraction to hide something much, much darker… For fans of Chuck Palahniuk, Bret Easton Ellis, Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Franzen _________________ `From the wondrous mind of Will Carver … a tour de force that covers life, death and everything beyond´ David Jackson Praise for Will Carver `One of the most exciting authors in Britain´ Daily Express `A smart, stylish writer´ Daily Mail `Incredibly dark and very funny´ Harriet Tyce `Unlike anything you`ll read this year´ Heat `Impossibly original, stylish, sinister and heartfelt´ Chris Whitaker `Weirdly page-turning´ Sunday Times `Ambitious, dark and funny´ Mike Gayle `A highly original state-of-the-nation novel´ Literary Review `Oozes malevolence from every page´ Victoria Selman `Arguably the most original crime novel published this year´ Independent `Mesmeric´ Guardian `Memorable for its unrepentant darkness…´ Telegraph `Perceptive and twisted in equal measure´ CultureFly `Pitch-dark, intelligent and utterly addictive´ Michael Wood `Unflinching, blunt and brutal´ Sam Holland `Equally enthralling and appalling´ James Oswald `One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction´ Alex North

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

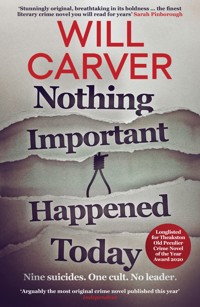

PRAISE FOR WILL CARVER

‘Will Carver’s mind works slightly differently to everyone else’s … Upstairs at the Beresford is superbly paced and remarkably inventive, a book that demands to be read in a single sitting’ M.W. Craven

‘From the wondrous mind of Will Carver, who is never afraid to innovate, Upstairs at the Beresford is a tour de force that covers, life, death and everything beyond’ David Jackson

‘As delightfully dark and wickedly inventive as ever, Upstairs at the Beresford is another captivating read from Carver with characters that stick around long after the final page is turned, whether you want them to or not’ S.J. Watson

‘I thoroughly enjoyed Upstairs at the Beresford, possibly for all of the right reasons – great characters, good but dark humour, and a completely engrossing story – but, undoubtedly for some of the wrong ones too. You don’t come to a Will Carver novel expecting a happy-ever-after fairytale ending. If this were a fairytale, it would be far more Brothers Grimm than Disney, and, got to be honest, that’s just the way I like it. Definitely recommended’ Jen Med’s Book Reviews

‘Yet again, Carver has delivered a corker! As deliciously dark as you would expect; the colour comes from the characters. Fabulously visual, Upstairs at the Beresford absolutely HAS to be a mini series’ Book Nerd

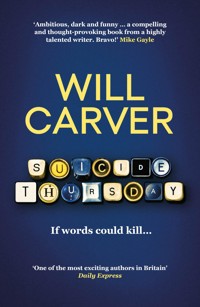

‘Ambitious, dark and funny … A compelling and thought-provoking book from a highly talented writer. Bravo!’ Mike Gayle

‘Incredibly dark and very funny’ Harriet Tyce

‘I fell in love with Carver’s murderous Maeve. This is an Eleanor Oliphant for crime fans. Carver truly at his best’ Sarah Pinborough

‘Psychologically chilling, pitch-dark, intelligent and utterly addictive. Will Carver is in a league of his own’ Michael Wood

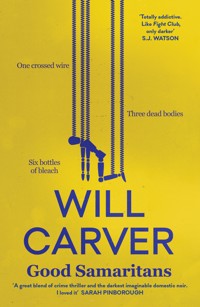

‘A darkly delicious page-turner’ S.J. Watson

‘Unflinching, blunt and brutal, Carver’s originality knows no bounds. Simply brilliant’ Sam Holland

‘Vivid and engaging and completely unexpected’ Lia Middleton

‘Dark in the way only Will Carver can be … oozes malevolence from every page’ Victoria Selman

‘Equally enthralling and appalling … unlike anything I’ve read in a very long while’ James Oswald

‘Creepy and brilliant’ Khurrum Rahman

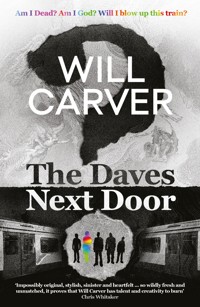

‘Impossibly original, stylish, sinister, heartfelt … Wildly fresh and unmatched, and once again proves that Will Carver has talent and creativity to burn’ Chris Whitaker

‘One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction’ Alex North

‘Will Carver is a unique writer. I loved Suicide Thursday’ Greg Mosse

‘Will Carver’s most exciting, original, hilarious and freaky outing yet’ Helen FitzGerald

‘Possibly the most interesting and original writer in the crime-fiction genre … dark, slick, gripping, and impossible to put down. You’ll be sucked in from the first page’ Luca Veste

‘Stirring. Ambitious. Irreverent. Compassionate. Completely devoid of giveable fucks’ Dominic Nolan

‘Move the hell over Brett Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk … Will Carver is the new lit prince of twenty-first-century disenfranchised, pop darkness’ Stephen J. Golds

‘A twisted, devious thriller’ Nick Quantrill

‘Challenging, perceptive and unexpectedly enlightening’ Sarah Sultoon

‘This one also put me through the emotional wringer … he takes our darkest, most hidden thoughts and puts them on the page, so we see our own monsters reflected back at us. Brutal and brilliant, as always’ Lisa Hall

‘Carver’s trademarked cynicism and contemptuousness run rampant here, but if you don’t mind being insulted, you’ll find a lot to laugh about and enjoy in this dark, dangerous novel’ Jack Heath

‘One of the most exciting authors in Britain. After this, he’ll have his own cult following’ Daily Express

‘A smart, stylish writer’ Daily Mail

‘Unlike anything you’ll read this year’ Heat

‘Weirdly page-turning’ Sunday Times

‘Arguably the most original crime novel published this year’ Independent

‘This mesmeric novel paints a thought-provoking if depressing picture of modern life’ Guardian

‘This book is most memorable for its unrepentant darkness’ Telegraph

‘Will Carver demonstrates an extraordinary talent for creating a figure of absolute selfishness and self-absorption and yet making it impossible to stop reading about his resentments, inadequacies and self-loathing … This is a masterful account of misery in many different forms’ Literary Review

‘SO original’ Crime Monthly

‘“Dark” is a word that encapsulates most of Will Carver’s books, but so is the word “brilliant” … Told from multiple perspectives, this is perceptive and twisted in equal measure’ CultureFly

LONGLISTED for Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year Award

SHORTLISTED for Best Independent Voice at the Amazon Publishing Readers’ Awards

LONGLISTED for the Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize

LONGLISTED for Goldsboro Books Glass Bell Award

UPSTAIRS AT THE BERESFORD

WILL CARVER

For Heaven’s sake.

‘What is terrible is not death but the lives people live or don’t live up until their death.’

—Charles Bukowski

CONTENTS

ROBERT JOHNSON 1911–1938

The legend of the Faustian bargain dates back almost five hundred years. A dissatisfied intellectual sells his soul to the devil at a crossroads in return for unparalleled knowledge and earthly delights. The deal is made for immediate reward without consideration for any future consequence.

In more recent times, the poster boy for such an act is the musician Robert Johnson. An average guitarist, the story tells of how he ventured to the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49, where he was met by a mysterious dark figure. Johnson handed over his guitar, the demon tuned it for him, played a couple of songs and returned the instrument along with the skills required to master and create the sound Johnson would become known for and, eventually, influence a league of future musicians, before being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Theories of a deal with the devil have long been associated with the likes of Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean, suggesting that Satan is quite the patron of the arts. Yet, no such fable appears to exist where a person made a pact to sell their soul for the sake of somebody else.

CROSSROADS

The problem is, you only make a list of the things you want to do in life when you find out you’re about to die.

You think a brain tumour is bad, try talking to the guy who wished he’d quit his job thirty years ago. Lung disease is a real bitch, too, but it’s better than a lifetime of caring what other people think, guessing what they say behind your back, not realising that you’ve focussed your energy in the wrong direction. And dementia is no fun for anybody, but it beats the hell out of regret.

What if you’d lived more in the moment?

What if you’d followed your passion?

What if you’d told that person how you really felt?

Death sucks, but the sorrow is only amplified when it follows a life not lived.

Time squandered.

Wasted on worry.

You logged into your work email over the weekend when you could have been swimming with dolphins or fucking your professor. And now there’s no time to put that right. There’s nothing left to enjoy.

‘Bowel cancer,’ says the doctor. ‘Stage four.’

Mr May looks at his wife and tears fall silently down his cheeks. His bottom lip quivers.

She asks, ‘How long?’

‘A few weeks, maybe. A month. Tops.’

Faced with the truth of his own mortality, Mr May thinks about his wife. How much he loves her, how much he has cherished his life with her, how much he appreciates her support. And then he thinks about all the things they never got to do together.

He starts to make a list. A few weeks. Maybe a month. Not long enough to do everything but it forces him to look at the things he really wants – be more specific. It makes him get excited rather than depressed. Motivation over desperation. He wants to create some focus for his remaining time with the great love of his life. It’s all he can do.

There’s a liberation that comes with making a bucket list while you still have life left in you. In the simplest sense, it, at least, keeps you active. There’s the opportunity to push the boundaries of your comfort zone, experience a sense of accomplishment that you probably are not receiving from your work. God damn, it could even make you more interesting, or at least seem more interesting.

It allows you to dream bigger. You want to become a rock star, a sports star, a porn star, whatever, you don’t have to sell your soul for that, you just have to open your mind a little. There’s a chance to create some kind of legacy. If you don’t leave it until some doctor tells you that you have a month left. Tops.

Mr May clicks out of his reverie. He looks up at the yellow-with-age ceiling of the doctor’s office and asks God what he can have done that was so bad to be judged and sentenced in this way. He could never tell his wife this, she is so devout. He waits for an answer that will never come. Faith evaporated upon diagnosis.

The shit in his body that used to work, doesn’t work now.

His wife is also angry about that.

‘What the hell are we going to do with a few weeks?’

It’s rhetorical, but the doctor answers, anyway.

‘My advice to you … Pray.’

He that committeth sin is of the devil; for the devil sinneth from the beginning…

GENESIS

The only thing scarier than the doorbell ringing at The Beresford is the sound of Jehovah’s Witnesses knocking at your door.

It’s not like they’re peddling double-glazed windows or light bulbs or home security. We need those.

It’s a tough sell.

It’s God.

But, you know, a skewed version. You’ve heard a few things. The bad stuff, probably.

Don’t fuck before you’re married.

Don’t fuck somebody who is the same sex as you.

Don’t even think about getting married and fucking somebody else.

Don’t smoke, don’t drink, don’t do drugs.

And the one everybody seems to remember – no blood transfusions. Even if you’re in hospital and will die as a result.

It’s a thankless task. Being ignored or having a door slammed in your face or taking verbal abuse because you’ve interrupted the family dinner.

Yet, nearly nine million people worldwide invited these strangers into their home, listened to what they had to say and joined the movement. Even after hearing all the bullshit that usually puts people off, membership increased. Impressionable minds. Real optimists. The kinds of people who would ask, ‘But what about all the good things Hitler did?’

Those Witnesses are playing the long game. But it seems to be working.

They could double their membership if they hired a social-media manager. But they’re not greedy. Only 144,000 of them will get to live in Heaven, after all, so it’s not worth lowering your chances of that. (Don’t worry, the rest of them will get to stay in a paradise on Earth. Probably the best silver medal of all time.)

As experiments go, it could be classed as a successful one.

Now, imagine knocking on all of those doors and instead of trying to sell a dream or an idea or an ideology to the people gracious enough to answer, you have to convince them to sell something to you. How much harder is that?

Sure, you offer them above-market price for their home, and they’ll pack up the next day and move on, no matter how much history and nostalgia lurks within those walls. You put a million on the table and ask for their child, a small percentage might consider it. Instead of money, you proffer fame, a long life, sexual prowess, health, safety, a legacy. Watch as things become more interesting.

Ask them what they really want.

See how they stumble.

The problem is, what you want from them is worth so much more than a new car or a twelve-inch dick. You can offer them their wildest dreams but it comes at a cost. It has to. They have to sacrifice something. It’s only fair.

For a place in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame or a star on a Hollywood sidewalk or your name on the patent for the iPod, the only exchange can be your soul. What is that worth to you? You want to walk in the corridors of power and have knowledge of events that you can never share with another living being?

Is that worth an eternity of unrest?

How many doors would slam in your face if you posed this question? How many times would you be told to ‘Go fuck yourself’ because the turkey roast is on the table?

Almost nine million Jehovah’s Witnesses recruited using a flimsy-at-best, door-to-door sales technique. How many people throughout history have sold their soul for personal gain?

It’s fewer than you think.

Knocking on doors isn’t the answer.

There has to be a better way.

The Beresford is old. It is grand. It has evolved with the people who have inhabited its rooms and apartments. It is dark and elephantine and it breathes with its people. Paint peels and there are cracks in places. It is bricks and mortar and plaster and wood.

It is alive.

And it never stops changing.

EXPERIMENT ONE: HOTEL BERESFORD

ROOM 728

There is a smoke that emanates from Danielle Ortega. Her voice is deep and husky. Although a woman only in her twenties, you could believe that she has had a cigarette hanging from her mouth since 1950. It’s the same when she sings. A couple of notes and you are dropped into some kind of jazz haze. Her every footstep is accompanied by the sound of a double-bass string being plucked. Her hair wafts to John Coltrane’s trumpet and her hips sway to the delicate tap of the snare drum.

You notice Danielle Ortega when she walks into a room or out on the street. She stands out. As though she has been mistakenly dropped into the world from another time, another place. She shouldn’t exist as anything other than old black-and-white film footage of Paris in the 1920s. But she does. Moving through the corridors like fire.

She adds grace to the notoriously noisy and difficult seventh floor of Hotel Beresford. The lift stops. She steps out and shuts the door behind her; it’s not automatic, it’s old metal that concertinas and offers little protection. There are screams from two separate apartments. Paint is flaking off the left-hand wall, like it’s damp, but it can’t be. A dog barks, even though there are no pets allowed here and the guy in 731 isn’t blind. A baby cries. A glass breaks. Cooking pots bang against one another. The boy from 734 is sitting outside, beneath the window again. He’s reading.

He has seen Danielle. He felt her first. Then he smelled her. Something fresh and floral against the backdrop of fried onion and wet walls.

‘Hey Danielle,’ he calls down the hall.

‘Hey Odie, watcha reading today?’ She turns the key to her door.

Odie lifts his book up.

‘That not too old for you?’

‘I’m smarter than I look,’ he smiles, white gravestone teeth against smooth black skin. Freckles on his cheeks. A bruise around his left eye. She knows his father hits both of them; Odie and his mother.

‘No doubt about that.’ She smiles back, knowing he is usually out there either because his parents are arguing or his mother is drinking. He’s ten years old, going on fifteen. A part of her wants to ask him in, but that would be inviting trouble. There’s a bang against the inside of his door and she watches him flinch.

She can’t help herself. ‘If things out here get … not okay, you come and knock for me. Alright? You know where I am?’ The dog barks again.

‘You’re the woman in 728,’ he says, like he is repeating something his mother has said before. Odie’s father has said things to Danielle in the hallway in the past. Unsavoury things.

I’ve seen you looking at the woman in 728.

‘That’s right. In fact, I’m that woman in 728.’

Odie might be smarter than his age but he doesn’t pick up on the nuance. His head drops back to his story and she enters her apartment.

Walking straight to the turntable in her lounge, she lays down a Billie Holiday record that she knows could never be played too loud on the seventh floor of Hotel Beresford.

She kicks off her shoes by the coffee table and looks at herself in the mirror, rubbing at the olive skin on her cheeks that hides just how tired she is. Danielle Ortega drops to her knees and rests her elbows on the orange sofa.

‘Dear God, please take care of that boy.’ She almost cries, but holds it in. If there is a God, Danielle Ortega’s voice is one He would want to listen to. It has been the ruin of many men. She continues, asking to keep him safe, get his mother’s drinking under control, stop the whoring around. She asks nothing for the father. Finally, she looks up and asks for a better gig than the one she has in town right now. One that pays better. One where she isn’t fighting with the club owner for taking a larger cut than was promised.

Something closer to The Beresford. Or, better, that pays enough that she could get out of this place. Because it does something to you, living in a building like this. You tell yourself you’re not like the couple shouting next door or the guy with the angry dog or the drug dealers and drug takers. You’re not bouncing off the walls in here or playing death metal at midnight on a Tuesday. You’re trying to earn your keep, doing the only thing you love.

She lights a cigarette. You’re not supposed to smoke in these apartments but everybody does. Drawing the smoke into her lungs, it seems stupid to ruin her instrument in that way, but that’s how she has obtained the sound she is known for.

The glass ashtray on the coffee table has been smashed in half, so she flicks ash into an old beer bottle left on the kitchen counter, before going to the fridge for a fresh one.

There’s a window behind the sofa that Danielle opens. She straddles the window ledge. One leg inside, over the back of the sofa, the other dangling freely outside, a hundred and twenty feet above the street below. She blows a plume of smoke towards the sky. A few doors down, a couple is doing the same thing, but she can smell the weed from here. She nods at them and they raise a joint in recognition.

At Hotel Beresford, it seems everybody is doing something that they shouldn’t.

The walls shake. Billie Holiday jumps. A door slams.

Her cupboard moves.

Danielle Ortega flicks the end of her cigarette down to the road below. Anyone else doing that looks disgusting but everything Danielle does is effortlessly cool. She’s tired. Almost nocturnal with the hours she keeps at the club, singing for her supper. She glides across the living area to the shoes she kicked off and picks them up. The place isn’t as tidy as she’d like.

The door rattles. Car horns blare outside. A gunshot downtown. Then another. One for every hundred veterans lying under cardboard in a doorway.

She opens the cupboard, kicks off her shoes, and the man tied up and gagged on the floor inside squirms when the light hits his eyes.

Odie’s father. With an indentation in his forehead that matches the corner of the broken ashtray on Danielle’s coffee table.

‘What the fuck am I going to do with you, huh?’ she asks, her sultry voice not doing anything for him on this occasion. He shouldn’t have struck the boy. And he shouldn’t have come grabbing at Danielle in the hallway.

Billie Holiday sings ‘All of Me’ and Danielle joins in, dancing in front of the open cupboard door, using her beer bottle as a microphone.

Odie’s abusive father is helpless. He watches her sway; lying upside down, it looks to him like she is dancing on the ceiling. He drinks her in. That voice. Such quiet power. Mesmerising.

The seventh floor of The Beresford might be the loudest but it’s not the worst.

Danielle closes the door, not knowing what she’s going to do. At least Odie is safe.

And she hasn’t killed anybody yet.

ROOM 734

An overweight, balding white man is adjusting his shirt collar as he exits, leaving the door ajar behind him. He sees the little kid outside, reading, and shakes his head in disapproval that the boy is not in school. He tuts and tightens his tie.

This guy, this judgemental prick, he took an hour out of the office and drove out of the city to Hotel Beresford to get his rocks off with a stranger. He dropped an extra twenty so she’d let him come inside her, too. And now he looks down on that woman for not sending her kid in to school.

The kid doesn’t look up from his book. He doesn’t want to see another man that isn’t his father coming out of room 734.

‘Otis Walker, I hope you haven’t been out here gassing to that woman from 728.’ She always full-names him when making a point or he is in trouble.

Odie looks up at his mother, half her left breast on display where she hasn’t straightened herself up properly.

‘No, Mama. But she’s nice.’

‘She ain’t nice, Odie. Nobody on this floor is nice. Hell, nobody in this building is nice. I don’t want you talking to anybody, okay?’

The boy nods, but he doesn’t mean it.

His mother looks out into the hallway and down towards the elevator, the top of a fat, bald head disappearing down towards the sixth floor.

‘Somebody needs to shut that damn dog up. Get in here, boy. Let’s fix you some snacks.’

Odie folds the corner of his page, shuts his book and pushes into 734. He can smell the sex on his mother, though he doesn’t know what that is. She looks around one last time, as though somebody is watching, shuts the door and locks it from the inside. She rests her head against the inside and breathes.

‘You alright, Mama? Want me to fix you a drink?’

Her heart sinks. Her son is ten years old, relegated to the hallway with his literature while she does unthinkable things to build up her getaway fund. And now he is asking whether she needs a drink. The kid is self-sufficient. He could make himself a sandwich. He could get her a glass of water. But what he’s really asking is if she is craving alcohol.

He’ll pour a cheap whisky and add a drop of water to take the edge off the burn. He can mix up a vodka and Coke. The kid can make coffee and he knows which glass the red wine goes in. Just as she knew what to pour for her own mother when she was the same age as Odie is now.

Diana Walker nursed her mother to death after her father left them both. A textbook shit dad, who went out for milk and never came back. Such a cliché. It broke her mother’s heart but, instead of focussing on Diana, she put all her efforts into the bottle.

As far as she can remember, her father wasn’t an abusive man. He rarely raised his voice. He worked. He was present. One day, he must have just had enough. She never wanted that for her kids. But there’s only ever two choices, it seems, when it comes to abuse and neglect, you either repeat the pattern or you break the cycle.

Diana was doing what her mother had done and, by God, she hoped that Odie’s father was just like hers. He went out last night and didn’t come home. Said he was playing poker uptown. It must mean that he’s winning. The stupid fuck only comes home when the money is gone.

It was a risk to take a morning appointment. That dumb fuck was supposed to take Odie to school on his way to work and that would have given her enough time to get the fat white guy in and out without fear of getting caught and beaten. She didn’t want to cancel. It was easy money. He never lasts that long and he’s not rough with her.

She looks at her watch. That dog is still barking. Even though her husband hits her, chokes her, spits on her, even though he broke her arm that time and her nose another time, even though he has hit her son, she finds herself worrying where he might be, that something may have happened to him.

Odie sees her staring at the window.

‘Mama, you sure you’re okay?’ He looks up at her with those big, brown doe eyes.

‘Fine, baby. I’m fine. Fix me a rum and Coke, would ya?’

Odie walks to the drinks cabinet.

‘And open the window, while you’re over there.’ She can smell the sex in here. And she knows what it is.

He opens the window.

The sound of traffic and voices and, a few windows down, singing. Drenched in smoke.

ROOM 731

Dogs are smart. They’re loyal and loving. Some people think they can sense earthquakes, though science is yet to show that as truth. They help the visually impaired. They can even be used to aid those with low self-esteem or anxiety issues.

People love dogs. And dogs seem to love people.

But the Doberman in 731 will not stop barking. And it’s pissing everybody off.

The couple in 733 have been banging against the wall, shouting, ‘Shut that fucking thing up or I’m gonna come in there and cut its damn throat.’

The neighbour in 729 went a step further and smashed a clenched hand against the front door. ‘Jerry, take your dog out for a walk, man. Fuck. It’s going stir-crazy in there, and we can’t listen to it anymore. You hear me? Jerry?’

Jerry didn’t answer then.

And he won’t answer now.

The dog hears singing and shouting and footsteps. It barks again.

It’s not trying to piss people off. It doesn’t need a walk. It’s calling for help.

For the first day, the obedient dog laid next to its owner, occasionally nudging him with a nose or a push of its back into Jerry’s leg. But it’s hungry as hell now and has been shitting in the corner of the bathroom for two days. And it’s definitely sad because there is an awareness that the owner hasn’t spoken a word or stroked or filled the water bowl or moved for forty-eight hours or so.

Jerry is on his back, a white foam dribbling from the side of his mouth. God knows what he took. Maybe it was too much, maybe it was just the wrong thing. Maybe he accidentally ate some peanuts. It doesn’t matter. Jerry is dead. And the poor dog knows it.

That’s why he’s barking all the time.

That’s why he’s scratching at the front door.

He’s calling for help. He’s not trying to annoy the neighbours. He’s asking for their attention. Luckily, Jerry has checked out of life a couple of days before he’s due to check out of Hotel Beresford, so somebody will be along to kick him out in a few hours.

Just as guests are not supposed to smoke in their rooms, or take drugs in their rooms, or be paid for sex in their rooms, there are no pets allowed. So, two days after losing his owner and companion, Jerry’s Doberman will lose his home. He’ll be tossed out onto the street with the other strays to fend for himself.

Any other hotel and this would be a major story.

‘Dead Junkie, Eaten by Dog at Hotel Beresford’.

But it won’t even register.

Just another day.

This type of thing happens all the time. They used to cover it up but, honestly, some crackhead overdosing and having his face chewed by a Doberman is the least of worries when it comes to all the things that are happening, right now, in the building.

RECEPTION

If something is going to get swept under the carpet or a bloodstained sheet is going to be bleached or burned, the order will come from downstairs. At reception.

And it will come from Carol.

The entrance to Hotel Beresford is art deco. Strict lines, geometry and arches showing cubist influence. The monochrome carpet screams elegance as it leads towards the desk that stretches the length of one wall, marble with chrome embellishments. Or, at least, it once looked that way. Back when writers and poets and dignitaries roamed the hallways and foyer.

It still feels lavish. Glamorous, even. But faded. And a little old-fashioned. Peeling paint and faded hopes.

Much like Carol.

Carol seems to age with the building. For every strip of wallpaper that gets ripped or falls away, Carol gets another wrinkle. When the front facade gets uplifted with a new paint job or some detail on the masonry, Carol turns up with a Botoxed forehead or facelift.

But not from a reputable surgeon. From somebody she saw advertising in the back of a magazine. Inexpensive treatments. The kind who has a clinic beneath a bridge that leads into the city. He’s got a reputation for double-bubble deformities with breast augmentation and there are a hundred guys knocking up their mistresses because the quick vasectomy they sprung for didn’t quite take.

A real hatchet job.

Much like Carol, herself.

You can see that she once possessed a natural beauty, probably entered pageants as a kid, but now she looks like Mickey Rourke in a skirt.

There’s no point trying to pinpoint her age. Some joke that she was born in the building. Others say she was found in the Beresford foundations. The smarter ones know that either of those could be true and it’s best not to fuck around with Carol.

She knows things.

Maybe she knows everything.

‘Complaint from the seventh floor. A dog barking. Non-stop, apparently,’ one of the receptionists alerts Carol.

‘How did somebody get a dog in here?’ Carol knows that guests get all sorts into the building. She damn well knows how it got in here, either through a fire-exit door that should set off an alarm but never does, or straight through the front door while her back was turned and other staff members let the mutt walk right by without giving a shit.

She’s saying it for the new girl. She’s young and enthusiastic and hasn’t been beaten down by the job that Carol once loved. The receptionist that passed on the message has been here almost as long as Carol has. Keith. In his fifties. Bald. Effeminate. Always wears a neckerchief, for some reason. When he started out, he spoke with a stutter but that’s all but disappeared over the years. If ever he feels that tongue getting tied, he starts to sing.

Guests love him.

Carol wouldn’t mind if he took a few days off or toned it down ten percent.

Nobody answers Carol’s question.

‘What room is this dog in?’

‘Um …’ Keith taps at the computer keyboard, hitting the return key with a flamboyance usually reserved for bullfighters. ‘731.’

‘Okay. Can you call security to go up there and see what’s up with this dog? Jerry is due to leave today, anyway.’ She looks at her watch. ‘Tell him he’s got an hour and they both need to get out. Send them down the back stairs.’

Nobody told Carol the name of the guy in 731. It’s just something she knows. Because it’s her job to know. That’s what makes her so good.

She pushes a section of the wall behind the reception desk and it seems as though a part of it moves. It’s so subtle that it’s almost a secret, but the opening leads to her office. It’s not something that shows up on the building plans, and the building is rumoured to have several false walls that can lead a person around Hotel Beresford, passing between the rooms, behind them, around them, undetected.

Who knows if any of that is true or just urban legend?

Carol probably does.

She disappears out the back, and Keith asks one of the security guards to take a trip up to the seventh floor and give the guest his marching orders.

Ollie draws the short straw. Of course. Two tours of Iraq hardened him. And, while many people thank him for his service, none of that helps when you get out of the army and the only job you can get is either a security guard or a nightclub bouncer. He’s been doing it for years. Treading water. Not going anywhere. Earning just enough for food and a few beers over the weekend. Luckily, his rent is cheaper now that his wife has left and somehow managed to take their house because she found him to be mentally abusive and emotionally unavailable after witnessing the horrors of war.

But she thanks him for his service.

It could be worse, he could be one of those veterans on the street with no legs, still wearing part of their uniform, holding up a piece of card and begging for money. He knows some of them. Real heroes. Discarded. He wishes he could help but he can just about take care of himself.

It’s been years since he’s seen any action but Ollie still looks as though he just got pushed out the back of a Chinook and parachuted into the hotel lobby with a knife in his teeth.

That’s why he gets sent upstairs.

There’s nothing that scares him anymore.

He shuts the door to the lift. It unnerves most people the first time they use it because it’s so open. At the height of Hotel Beresford glory, somebody was employed to ride the lift all day and take the guests to their floor. A little guy called Carlyle. He’d tuck himself into the corner and spin to life as soon as anybody stepped in. He rode that lift with politicians, hookers and rock stars. Often at the same time.

Nobody really knows what happened to him. Hotel Beresford became a place that no longer required a designated staff member to operate the vintage lift. A decision wasn’t made to terminate that position, it just faded out. And then, one day, somebody realised that Carlyle was no longer there.

Ollie can hear the dog before he even steps out of the lift. He can hear a couple shouting and somebody singing along to what sounds like Billie Holiday. And he can smell weed and sex from the fat, bald guy who got off at ground level as Ollie stepped inside the lift.

He knocks on 713.

‘Er … Jerry?’ It may be his military background but it doesn’t feel right to call somebody he doesn’t know by their first name. Ollie would feel more comfortable and respectful to refer to the guest as Mister Whatever.

The dog is barking and scratching against the back of the door. It sounds panicked. Ollie hits it harder and calls for Jerry again. He wants to cut the noise. The cars outside, the music across the hall, all the voices. He doesn’t have PTSD but the crescendo of sounds is reminiscent of war.

‘Jerry, I’m going to need you to open this door, your dog sounds in distress.’ Under his breath, ‘You’re not even supposed to have a fucking dog in here.’

‘Everything okay?’ A voice comes from behind Ollie and he jumps, turning quickly and setting himself to fight.

‘Jesus Christ!’ Ollie says, facing the person.

‘Not quite.’ He almost laughs.

‘Mr Balliol. What are you … I mean, where did you … What are you doing on the seventh floor?’

Mr Balliol lives in the penthouse. There is only one suite on the top floor. Balliol takes up every inch. The only access is from the one lift at Hotel Beresford, and the top floor requires a key. The only way onto the roof is to go to the end of the corridor on the ninth floor and take the fire escape ladder, which runs up the outside of the building.

Nobody disturbs Balliol. Somebody must go up and clean his place, he’s too rich to do it himself. But nobody asks questions about it. Carol will know, surely.

Mr Balliol doesn’t answer Ollie’s question about why he is there or where he came from. Instead he tells him, ‘I think you’re going to have to bust the door down. Seems like Jerry is incapacitated.’ Again, there’s a flicker of glee on his face. He’s definitely not concerned.

What is he doing on the seventh level?

Ollie looks back down the corridor at the caging around the lift shaft. The lift is on another level. Balliol couldn’t have arrived on this floor that way.

‘That dog could go crazy if I kick the door down.’

‘He could be going crazy because of what he can see beyond that door.’

Ollie pictures a guy hanging from the rafters. Wouldn’t be the first time.

‘I’ll go and get the key.’

‘Best kick it down, now, Ollie.’

‘Ah, fuck. Stand back, please, Mr Balliol.’

Balliol does as he’s asked and Ollie warns Jerry that he’s coming in. He’s worried that he’ll kick the door and hurt the dog or the dog will go to attack him for entering the room but he has no choice. He tells the dog to go and fetch Jerry, hoping it will go back inside for a second while he knocks through.

Ollie takes a step back from the door, holds out an arm for Mr Balliol to stand behind. A woman shouts something in another room. The dog isn’t barking. The car horns continue. He lifts a knee to his chest and cycles his foot forward into the door, splitting the frame on his first attempt. He follows up swiftly with a shoulder and bursts inside room 731 to a Doberman sitting calmly next to his owner, lying on the floor, obviously dead.

‘Shit,’ Ollie says under his breath. Then he turns back to apologise to Mr Balliol and shield him from the scene ahead. But he is gone.

ROOM 724

Not everybody on the seventh floor of Hotel Beresford is a lowlife. The Zhaos are here for a reason. They’re sensible and conscientious. And they’re not here to make friends, either. They’re here to do a job. They’re focussed on their end goal, which is to get the hell out of there.

Daisy Zhao doesn’t want to live in the city. She doesn’t even want to live this close to the city. She’s young, like Jun, so they can’t get onto the property ladder. And there are no wealthy parents to help them out.

They’re going at it alone.

So they will nod the occasional acknowledgement in the hallway or hint at a morning smile to the woman who smokes out her window a few doors down but, to the Zhaos, it’s them against the world. It’s their struggle, their fight, their goal to have the most frightfully average and unremarkable life in suburbia. Couple of kids. Maybe a dog. A front lawn with a white picket fence. It’s not the American dream but it is their dream.

And Hotel Beresford will help make that a reality. Because the seventh-floor prices are so cheap, the Zhaos can work and set enough money aside each month to build a sizeable deposit for the home they desire. It’s the place where they will really start their lives together. Not here in room 724, this is temporary.

Fit for purpose.

Purgatory.

But a pretty purgatory once Daisy Zhao has turned her hand to the interior design of their one-room palace. There are pieces of up-cycled flea-market furniture and salvaged light fittings and soft furnishings that add a pop of colour. Even with a lengthy rental period like the Zhaos’, guests are not permitted to paint the walls.

The place is immaculate.

Delicate.

Much like Daisy herself.

Jun loves her. He adores her quietness, her control and her poise. She is beautiful to him. Porcelain skin and striking green eyes. They are content in silences and engaged when in conversation. They fit together. It’s not passionate but it is affectionate. They are devoted to one another and their provincial project.

From the outside, they can come across as standoffish and stuffy but that’s not the case. Looking in at anybody’s life whether from a distance or behind the filter of social media, it’s easy to get the wrong impression. They have their routine now. Work. Rest. Clean. Prepare food. Make love twice a week. And smoke a joint on the window ledge each morning.

The Zhaos have been at Hotel Beresford for over a year. They’ve put more than twelve grand aside already by living as frugally as possible – with the exception of the weed habit. They keep the money in a high-interest account rather than a shoe box at the back of the cupboard. They only need fifteen to put down as a deposit but they’re talking of pushing on for twenty because it doesn’t seem like much of a stretch.

You can remove yourself from Beresford life, stay out of people’s way, keep your head down, be polite but not forthcoming, and you can make the place work for you. You can even get out. You can leave whenever you want to.

But there’s always a danger.

You can stay longer than you need, get greedy, get lazy, get comfortable. And that’s when things can change. The building knows.

ROOM 728

Danielle hears the commotion outside her room and saunters towards her own front door, Billie singing ‘Strange Fruit’ behind her, Danielle hums along.

She steps up to the peephole. One of the security guards is standing in the hallway. He’s looking all around as though he’s expecting somebody to be watching him. It’s odd behaviour. Beyond the muscular man, she notices the door opposite and to the left is hanging off one hinge. She can’t see Jerry on the floor but she can just make out the dog that has been annoying everybody. She listens carefully but there is no barking left.

Danielle could go out and ask what is happening, she could play the role of the concerned neighbour. Maybe she could just go into the hallway and have an obvious snoop.

That’s not how it works at Hotel Beresford.

You don’t get involved.

You turn a blind eye.

You let things slide.

Everyone has their own shit going on. Including Danielle.

‘Oh, this place.’ She looks at her watch and floats back into her lounge area. She needs to sleep. Her life is not normal. She’s almost nocturnal. Singing until the early hours, drinking afterwards. But there’s no downtime at Hotel Beresford, especially on the seventh floor. If you want to rest, you have to learn to live with the noise. The thrum of the city just beyond. The music. The arguments. The security guards kicking down the door of your neighbour.

Danielle lowers the blind that covers the window she was just sitting at and smoking. It’s darker, and that tricks her brain into thinking it’s also quieter. Just the ticking of the clock, the haunting sound of Ms Holiday’s voice coming through the speaker at her feet as she lies down on the sofa, pulling a blanket around her slender frame.

The door to her shoe cupboard trembles. She watches it and shakes her head, rolls her eyes. She wriggles her toes in time to the music and sings.

Here is a fruit…

She starts to drift.

…crows to pluck

Her eyes close.

…for the wind…

ROOM 724

Jun threw a smile and lifted his eyebrows slightly at the woman smoking a cigarette out of her window a few rooms across from the Zhaos’ place.

She is the opposite of Daisy. Long legs, sprawled either side of the window ledge. She’s cool. Alluring. Jun doesn’t even like the look or smell of normal cigarettes but there’s something about that woman, it suits her. It’s sexy. He doesn’t want to act on it. He’s not thinking of knocking on her door and getting smashed in the head by an ashtray. He’s not imagining her while making love to his wife, he’s just momentarily captivated each morning.

Daisy is too small to pull off the straddled look. She is so petite, she can sit outside on the ledge with her legs crossed and still have room around her. Jun has to dangle his legs over the side. It should be scary to do what they are doing while up at that height but it’s not. It’s safe enough. Even while smoking a joint.

They’ve been doing it for months.

In every other way, they are straight, methodical, tidy. This is their only indiscretion. They see the people beneath them on the streets, homeless and begging for money for their next fix, whether it’s a bottle of vodka or a hallucinogenic or the latest fashionable opiate. The Zhaos are not like that. They’re not addicted.

It’s a ritual.

The Dutch manage to smoke weed all the time while raising a family and holding down a full-time job. And they all speak six languages. That’s how the Zhaos see themselves. Completely in control of everything. Their destiny is in their hands.

Then Jun’s phone rings.

And they lose a little control.

‘You’re kidding?’ he says.

Daisy mouths, What’s going on?

Jun holds up a finger. Daisy gives him a look that tells him she doesn’t appreciate that gesture.

‘Of course. That’s great. Yes. I mean, neither of us will be able to get there today but tomorrow works, for sure.’ He smiles at Daisy to try to diffuse her mood and nods as though the person at the other end of the line can see him. ‘Okay. Perfect. See you then.’

Jun hangs up.

‘What was that?’ Daisy asks. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Come inside.’

‘What?’

‘Come inside. I don’t want you getting excited out on this shelf.’

Jun swings himself around and heads back in through the window. Daisy flicks ash into the wind and crawls along the ledge to follow her husband.

‘Come on, then. What is it?’

‘That was the estate agent. He’s got another house, same area as the one we liked but the guy is looking for a quick sale. His wife left or something and she wants half the money.’

‘I thought we agreed we’d get to twenty grand.’

‘I know what we agreed, Daisy, but he says the sellers will take lower than the asking price just to get shot of it, so that they can move on. We’ve got enough saved. We can get out of here, start our lives now.’

Daisy doesn’t feel comfortable with spontaneity but this has long been their dream and, through sheer luck, there is a chance it is about to come true.

HOTEL BERESFORD

The building is just outside the city, so it feels metropolitan but also, somehow, rural. The bright lights and skyscrapers are visible, they’re within touching distance, but the rates are much lower out here.

They’re lower still because Hotel Beresford has so many rooms. And that means it’s always full.

It has to be.

There’s one entrance. Double doors. Glass with a polished chrome frame. There’s a revolving door next to this, harkening back to a golden age when this place was vibrant and buzzing and new.

The ground floor is the reception. There’s an area to one side where guests can meet. There are tables to sit at and drink, and one wall houses a sizeable book collection. It’s not a library but it adds to the grandeur. On the other side of the entrance is a small apartment that only Carol can use as she manages the building. She doesn’t live there all the time, she has her own place further downtown, but it is logistically beneficial for her to have a crash pad for those longer shifts.

To the right of the reception desk there is a luxurious staircase that leads up to the second-level restaurants and bars and, on the other side of the desk is the corridor, lined with black-and-white art, that leads around to the lift, which takes all the guests to their rooms.

Pressing buttons one or two will take you to the ground floor. A quirk that nobody has ever attempted to rectify.

Floors three to six are the single-occupancy rooms. Each has a double bed, shower and toilet facility. They’re ideal for your backpacker types, anyone having an affair, businessmen travelling to the city for a few days of work, and some of the local women who charge for services by the hour.

Floors seven to nine are different. They offer a living area, kitchenette and separate bedroom. Guests can cater for themselves. These rooms attract people wanting to stay for the week, maybe two. The price is so reasonable that you’ll often find visitors that have been there over a month. Maybe they’re between properties or they’ve been kicked out of the family home. A lot of the time, they’re trying to escape something. But it’s so reasonable, it’s easy to look at these rooms as short-term lets.

Danielle has already been here for six weeks. Odie’s father lost his job and their home but got back into work a few weeks ago. They’ve been living in the hotel for a couple of months because they didn’t have the lump sum to put down for a rental deposit while they were getting back on their feet. Jerry brought his Doberman up the back stairs about ten days ago and the dog has been on its own for two more. For some reason, the seventh floor has always been the noisiest. Nobody knows why. Not even Carol.

Each floor looks the same yet somehow has its own unique landscape; it’s known for something particular. A celebrity affair. A mysterious death. A legendary party. Rumours that a serial killer crashed there between sprees. Rock stars smashing up rooms. Writers creating their masterpieces. Some is legend, much is true. All is talked about. With fondness, fascination and morbid curiosity.

Then there’s that top floor. The one level that remains a mystery. The conjecture, the stories, are far-fetched and debauched and absurd.

Bluff. Banter. Balderdash.

Keith heard that Mr Balliol took twelve women up there and made love to every single one over the course of an evening. That he once called down to the front desk and asked someone to bring up a bowl of cocaine for breakfast. And he also made a business deal inside the lift that gave him enough to live on for hundreds of years.

That he has been here from the beginning.

Before Carol and the revolving door.

That he knows the building better than anybody. He’s always watching and can see everything.

All utterly ridiculous. And true.

THE PENTHOUSE

It has been said that the best way to get rich is not to earn a ton of money, it’s to not spend any. You could initially be forgiven for thinking that Mr Balliol is thrifty based on the minimalist approach to the penthouse suite.

Oak floors throughout. Stainless-steel appliances. Marble worktops. The opulence one might expect from the wealthy. But a closer look uncovers furniture that is centuries old. Abstract art pieces. Paintings. Sculptures. Rare books. A fireplace that appears to have fallen out of a gothic cathedral. And a mirror, so tarnished with age that the reflective surface is almost all peeled away or black. Not functional but beautiful in its patination.

The rooms are sparse but the pieces that do exist hold history.

This is not a floor that can be rented for the night. It is, like the lower levels, a single-occupancy space but it has no free dates for, at least, another few hundred years.

Balliol owns this floor.

Some things aren’t for sale. And the highest floor of the Hotel Beresford building is certainly one of them.

The entire penthouse apartment is almost open plan. The kitchen bleeds into the dining area – a table made for twenty people that is mostly used by one. The lounge falls into a library and games room. There are walls but no doors. Sometimes they’re not even solid, just a series of vertical posts cut from oak to match the floors, differing heights to add some sculptural interest. It’s possible to look through the gaps into the next room. It is beautiful. Clean and timeless.