6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

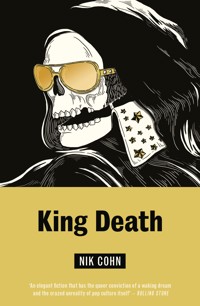

Eddie is a strange man with an extraordinary talent that makes him the 'performer' he is. Eddie administers Death. His subjects, he explains, are not afraid, but are thrilled and transported. To Eddie, Death is completion, and he finds fulfilment, satisfaction, and pride in each job he carries out. When Seaton Carew, America's most successful TV entrepreneur, chances to witness Eddie in action, Eddie's career is altered. Overcoming many obstacles, he and Seaton literally ride to glory on the Deliverance Special, a train carrying King Death and his huge entourage all over America. But then a disturbing change comes over Eddie and threatens to topple him from his grisly throne... Part nightmare, part modern fairytale, Nik Cohn has written a bizarre fable for our time. In a cool and highly original style Cohn captures its sickness and horror yet stays true to its grandeur and allure.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

KING DEATH

Eddie is a strange man with an extraordinary talent that makes him the ‘performer’ he is. Eddie administers Death. His subjects, he explains, are not afraid, but are thrilled and transported. To Eddie, Death is completion, and he finds fulfilment, satisfaction, and pride in each job he carries out.

When Seaton Carew, America’s most successful TV entrepreneur, chances to witness Eddie in action, Eddie’s career is altered. Overcoming many obstacles, he and Seaton literally ride to glory on the Deliverance Special, a train carrying King Death and his huge entourage all over America. But then a disturbing change comes over Eddie and threatens to topple him from his grisly throne…

King Death is part nightmare, part modern fairytale and wholly original.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nik Cohn is the original rock & roll writer. Arriving in London from Northern Ireland in 1964, aged 18, he covered the Swinging Sixties for The Observer, The Sunday Times, Playboy, Queen and the New York Times and he published the classic rock history Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom in 1968. Later he moved to America and wrote Tribal Rites of the Saturday Night that inspired Saturday Night Fever. His other books include Rock Dreams (with Guy Peellaert), Arfur Teenage Pinball Queen (which helped inspire the Who’s Tommy) and Yes We Have No.

PRAISE FOR NIK COHN

‘A thrilling, inspirational read’ –Guardian

‘Set the template for a whole new style of rock journalism, informed, irreverent, passionate and polemical’ –Choice Magazine

‘The book to read if you want to get some idea of the original primal energy of pop music. Loads of unfounded, biased assertions that almost always turn out to be right. Absolutely essential’ –Jarvis Cocker,Guardian

‘Cohn was the first writer authentically to capture the raucous vitality of pop music’ –Sunday Telegraph

TO ELVIS AND JESSE,

THE PRESLEY TWINS; AND

FRANNY MAE LIPTON

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

1

One day, towards the end of a long dry summer, Seaton arrived in Tupelo and stopped at the Playtime Inn. It was a stifling afternoon, the town lay in a stupor and, for lack of anything better, he stood at his bedroom window, half-hidden behind a net curtain, looking out across the street.

From where he was stationed, he could see three shopfronts: a Chinese laundry, a pool hall, and a saloon called The Golden Slipper. Between them, they occupied perhaps a dozen yards of sidewalk. In addition, if Seaton craned his neck, he could just make out the first three letters of a gilded nameplate – wil, as in wilkes & barbour (Noted Upholsterers).

Within this frame, the action was severely limited. An antique Chevrolet was parked outside the pool hall, a mulatto woman was scrubbing the steps of the saloon and a mongrel lay panting beneath a lamp post. In the doorway of the Chinese laundry, there stood a man in a heavy black overcoat, black gloves and a black slouch hat, and between his legs there was a small black suitcase.

Seaton watched, and time dragged by very slowly. He felt sticky and unclean and, from time to time, to ease his boredom, he would turn away and flop down on his bed, or splash his face with lukewarm water, or help himself to a cigarette. He was an Englishman born and bred, and at the bottom of his suitcase, there was Wisden, the Cricketers’ Almanack, for 1921; three old school ties, all different; and a photograph of the Queen Mother.

So the afternoon passed. Propped up behind the glass like a tailor’s dummy, Seaton began to nod, and a large blue fly settled on his nose. The Chevrolet drove away, the mulatto maid finished her scrubbing, the mongrel wandered off round the corner. Finally, only the man in black remained, and even he was lost in shadow, all except for his shiny black boots, which protruded an inch into the sunlight, toecaps glinting.

Possibly Seaton drifted off into a doze, perhaps he simply ceased to register. At any rate, when a siren sounded on the corner, it took him by surprise and his head jerked, his eyes opened wide.

It was past five o’clock. The sun had lost its force and his sweat had turned cold on his flesh, a sensation which made him shudder. Wincing, he shook himself and stretched and yawned, and he was just on the point of moving away when a stranger in a blue pin-striped suit emerged from the pool hall, and began to stroll down the block.

He moved with bent head and slouched shoulders, and it was not possible to make out his features. From a distance, however, he seemed roughly the same age and build as Seaton himself – squat and stubby, slack-fleshed – and he did not walk so much as amble, splayfooted.

As he came abreast of the laundry, he produced a cigar and paused for a moment to light it, holding it up to his nostrils, rolling it lovingly between his thumb and forefinger. Immediately, the man in the black overcoat stepped out from the doorway, hand outstretched, as if to proffer a light, and the stranger half turned to meet him, inclining his head.

At this moment, something odd occurred. The two men, as they touched, appeared to mesh. There was no noise, no semblance of a struggle, but the man in black, flowing into the stranger’s flesh, seemed to pass straight through him and come out on the other side, all in one smooth motion.

For an instant, as he stepped clear, his face caught the light and his eyes were seen to gleam and sparkle, like tiny mirrors refracting. Before Seaton had time to focus, however, they had dimmed again and he had turned his head. Stepping down from the sidewalk, momentarily eclipsing the wil of wilkes & barbour, he tucked his black suitcase underneath his arm and, sauntering, he disappeared off the edge of the frame.

The man in the pin-striped suit was left behind. For several seconds, he hung without moving, cigar still halfway to his lips, head still inclined towards the empty doorway, as though he were listening to something very faint and difficult, which required his utmost concentration. Seaton could hear dance music playing on a radio, saw a flutter of pink silk in the depths of The Golden Slipper. Then the stranger gave a sigh and, folding gently at the knees, he slid down on to the sidewalk, where he twitched three times and was still.

That same evening, when night fell, Seaton crossed the street to The Golden Slipper, where there were blondes in tight red dresses, slow sad country songs on the jukebox and men who drank to forget, and he sat down alone in a dark corner booth, consuming large brandies.

Once, he had been a choirboy; in all his childhood snapshots, he appeared as a perfect dimpled cherub, pink and round. But now he had reached his middle thirties and that first pure glow was dulled. His pinkness had grown mottled, his dimples had turned into embryonic potholes and, though he was not exactly fat, he sagged, like puff pastry gone wrong.

Tonight he wore a blue naval blazer with shiny brass buttons, cavalry twills and a pair of chukka boots, made in Japan, which had been polished so hard and so often that they gleamed bright lemony yellow. But his shirt was soiled, there was a button missing from his cuff, and his tie, though Old Carthusian, was stained with tomato ketchup.

Inside The Golden Slipper, soft glowlights turned from midnight blue to purple, from gold to fluorescent pink, and the blondes, both strawberry and peroxide, were ranged in a spangled line along the bar, silently filing their fingernails.

Seaton got drunk to make time pass. When the jukebox played a song about honky-tonk angels, one of the blondes slid in close beside him, softly squeezing his thigh. ‘Stranger’, she called him, which pleased him very much. But she smelled too strongly of liquorice, her eyes were too red from weeping. So he gave her a dollar and told her to leave him be.

When he looked up again, he saw that the man in the black overcoat was sitting at the bar, sipping Dr Pepper through a straw. Even off duty, he still wore his black hat, black gloves and shiny black boots, and his little black suitcase lay snug between his feet.

For forty-seven seconds, the Englishman did not move. Then he crossed the floor and sat down on the next stool. ‘I saw you,’ he said. ‘I was standing at my window, I saw you in the doorway and I watched everything that happened.’

The man in black did not reply, made no move, gave no sign of anything. Impassive, he took another sip of his Dr Pepper and gazed at the reflections in the back-bar mirror, where he saw, on the stool next to his, a small rumpled party with a wet mouth, wet puppy-dog eyes and fingernails bitten down to the quick. ‘I witnessed every detail,’ Seaton said. ‘And I felt I simply must tell you, I was overwhelmed.’

‘Thank you,’ said the man.

‘I’ve never seen anything like it; not on TV, nor even at the movies. The way you flowed right through him, all in a single movement, and he did not struggle in the slightest – if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I would not have believed it.’

‘You are most gracious,’ said the man.

‘I was thrilled. Perhaps I ought not to say that, perhaps it isn’t quite dignified. But my blood began to roar, my temples began to pound and do you know, when you had departed and the stranger was still, I felt as limp as a dishcloth.’

At this, the man in black, who did not take his eyes off his own reflection, made a minuscule adjustment to the angle of his hat brim, drawing it just a fraction lower across his left eye.

There was a brief silence; then the Englishman stuck out his hand. ‘Permit me to introduce myself,’ he said. ‘My name is Seaton Carew and I come from across the seas.’

‘They call me Eddie,’ said the man.

And the two of them shook hands.

Flushed with triumph, Seaton ordered another large brandy for himself, another Dr Pepper for his new friend, and he raised his glass in a toast. The blondes chewed gum, the jukebox played a song about lost love and loneliness: ‘Eddie,’ said Seaton.

‘Mr Carew,’ said Eddie.

And they drank.

Eddie’s voice was a softest Mississippi drawl, hardly more than a whisper, but his language might have come from anywhere. When he turned towards his companion, his face was entirely bland and empty, bereft of age or meaning. From deep inside his overcoat pocket, he produced a pair of knucklebone dice, and he began to roll them on the bar, idly noting their progressions. Meanwhile, Seaton drank and watched.