1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

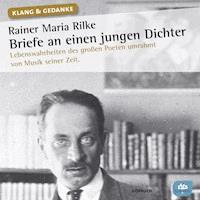

Letters to a Young Poet, by Rainer Maria Rilke, is a profound and introspective collection of ten letters written between 1903 and 1908 to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young aspiring poet. In these letters, Rilke offers deeply personal reflections on the creative process, solitude, love, and the challenges of artistic life. Rather than providing conventional advice, he encourages Kappus to look inward, to trust in his own experiences, and to embrace uncertainty as a vital part of artistic and personal growth. Since its publication, Letters to a Young Poet has resonated with generations of readers, artists, and thinkers. Its meditative tone and timeless insights extend beyond poetry, offering guidance to anyone navigating the complexities of life and self-expression. Rilke's emphasis on patience, authenticity, and inner development has made the book a cherished companion for those seeking meaning in their creative or emotional journeys. The enduring appeal of Letters to a Young Poet lies in its quiet wisdom and its invitation to embrace solitude as a space for transformation. Rilke's words continue to inspire by affirming the power of introspection and the necessity of living one's questions fully, with openness and courage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 107

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Rainer M. Rilke

LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET

Contents

INTRODUCTION

LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET

CHRONICLE 1003-1000

INTRODUCTION

Rainer Maria Rilke

1875 – 1926

Rainer Maria Rilke was an Austrian poet and novelist, widely regarded as one of the most significant and lyrical voices in modern European literature. Born in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Rilke is celebrated for his introspective poetry, spiritual themes, and philosophical depth. His works explore the boundaries between the visible and invisible, the sacred and the mundane, often addressing the human experience through a deeply personal and meditative lens.

Early Life and Education

Rainer Maria Rilke was born into a German-speaking family and experienced a turbulent childhood marked by parental conflict and frequent relocations. Initially pressured by his parents into a military career, he eventually abandoned it to pursue a more artistic and intellectual path. He studied literature, art history, and philosophy in Prague, Munich, and Berlin. His early travels through Russia with Lou Andreas-Salomé, a writer and intellectual with whom he had a close relationship, deeply influenced his spiritual and artistic development, notably shaping his poetic sensibility.

Career and Contributions

Rilke’s poetry is known for its profound emotional and existential insight, often touching on themes of solitude, beauty, transience, and the ineffable. Among his most renowned works are the Duino Elegies (1923) and the Sonnets to Orpheus (1923), both written during a burst of creative energy after a long period of silence. The Duino Elegies, composed over a decade, reflect a mystical and philosophical inquiry into life, death, and the divine, while the Sonnets to Orpheus explore transformation, artistic creation, and the role of the poet.

Rilke also wrote The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910), his only novel, a semi-autobiographical work that blends narrative with philosophical introspection. The novel captures the alienation of a young man living in Paris, struggling with memories, fears, and the disorientation of modern urban life. Through fragmented reflections and symbolic language, Rilke delves into the psyche of the modern individual, anticipating themes later explored by existentialist writers.

Impact and Legacy

Rilke's work marked a turning point in German-language poetry, moving away from rigid forms and traditional subjects toward a more introspective and metaphysical exploration of existence. His lyrical innovations and spiritual intensity influenced a wide range of writers and thinkers, including Hermann Hesse, W. H. Auden, and even contemporary poets and philosophers. Rilke redefined the role of the poet as a mediator between the visible and the invisible, someone who listens deeply to life’s mysteries and articulates them with beauty and precision.

His mastery of language, use of symbolism, and philosophical openness make his poetry resonate across cultures and generations. His influence extends beyond literature into theology, psychoanalysis, and the arts, as his reflections on solitude, suffering, and transcendence continue to inspire deep intellectual and emotional engagement.

Rainer Maria Rilke died in 1926 at the age of 51, from leukemia, in Switzerland. True to his poetic ideals, he remained dedicated to his craft until his final days, even refusing pain medication so that his consciousness would remain clear. After his death, his reputation grew steadily, and today he is considered one of the most important poets of the modern era.

Rilke’s legacy lies in his unique ability to render inner experience into lyrical form, transforming personal insight into universal meditation. His work invites readers to confront the mysteries of existence with openness and reverence, establishing him not only as a poet of great technical skill but as a spiritual guide whose voice continues to echo across time.

About the work

Letters to a Young Poet, by Rainer Maria Rilke, is a profound and introspective collection of ten letters written between 1903 and 1908 to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young aspiring poet. In these letters, Rilke offers deeply personal reflections on the creative process, solitude, love, and the challenges of artistic life. Rather than providing conventional advice, he encourages Kappus to look inward, to trust in his own experiences, and to embrace uncertainty as a vital part of artistic and personal growth.

Since its publication, Letters to a Young Poet has resonated with generations of readers, artists, and thinkers. Its meditative tone and timeless insights extend beyond poetry, offering guidance to anyone navigating the complexities of life and self-expression. Rilke’s emphasis on patience, authenticity, and inner development has made the book a cherished companion for those seeking meaning in their creative or emotional journeys.

The enduring appeal of Letters to a Young Poet lies in its quiet wisdom and its invitation to embrace solitude as a space for transformation. Rilke’s words continue to inspire by affirming the power of introspection and the necessity of living one's questions fully, with openness and courage.

LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET

LETTER ONE

Paris.

February 17th. 1903

My dear sir.

Your letter only reached me a few days ago. I want to thank you for its great and kind confidence. I can hardly do more. I cannot go into the nature of your verses; for all critical intention is too far from me. With nothing can one approach a work of art so little as with critical words: they always come down to more or less happy misunderstandings. Things are· not all so comprehensible and expressible as one would mostly have us believe; most events are inexpressible, taking place in a realm which no word has ever entered, and more inexpressible than all else are works of art. mysterious existences. the life of which. while ours passes away, endures.

After these prefatory remarks. let me only tell you further that your verses have no individual style. although they do show quiet and hidden beginnings of something personal. I feel this most clearly in the last poem, "My Soul." There something of your own wants to come through to word and melody. And in the lovely poem "To Leopardi" there does perhaps grow up a sort of kinship with that great solitary man. Nevertheless the poems are not yet anything on their own account. nothing independent, even the last and the one to Leopardi. Your kind letter, which accompanied them, does not fail to make clear to me various shortcomings which I felt in reading your verses without however being able specifically to name them.

You ask whether your verses are good. You ask me. You have asked others before. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are disturbed when certain editors reject your efforts. Now (since you have allowed me to advise you) I beg you to give up all that. You are looking outward, and that above all you should not do now. Nobody can counsel and help you, nobody. There is only one single way. Go into yourself. Search for the reason that bids you write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. This above all-ask yourself in the stillest hour of your night: must I write? Delve into yourself for a deep answer. And if this should be affirmative, if you may meet this earnest question with a strong and simple "I must," then build your life according to this necessity; your life even into its most indifferent and slightest hour must be a sign of this urge and a testimony to it. Then draw near to Nature. Then try, like some first human being, to say what you see and experience and love and lose. Do not write love-poems; avoid at first those forms that are too facile and commonplace: they are the most difficult, for it takes a great, fully matured power to give something of your own where good and even excellent traditions come to mind in quantity. Therefore save yourself from these general themes and seek those which your own everyday life offers you; describe your sorrows and desires, passing thoughts and the belief in some sort of beauty-describe all these with loving, quiet, humble sincerity, and use. to express yourself. the things in your environment. the images from your dreams, and the objects of your memory. If your daily life seems poor. do not blame it; blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to call forth its riches; for to the creator there is no poverty and no poor indifferent place. And even if you were in some prison the walls of which let none of the sounds of the world come to your senses-would you not then still have your childhood, that precious. kingly possession, that treasure-house of memories? Turn your attention thither. Try to raise the submerged sensations of that ample past; your personality will grow more firm. your solitude will widen and will become a dusky dwelling past which the noise of others goes by far away.-And if out of this turning inward. out of this absorption into your own world verses come. then it will not occur to you to ask anyone whether they are good verses .. Nor will you try to interest magazines in your poems: for you will see in them your fond natural possession. a fragment and a voice of your life. A work of art is good if it has sprung from necessity. In this nature of its origin lies the judgment of if: there is no other. Therefore. my dear sir, fknow no advice for you save this: to go into yourself and test the deeps in which your life takes rise; at its source you will find the answer to the question whether you must create. Accept it. just as it sounds. without inquiring into it. Perhaps it will turn out that you are called to be an artist. Then take that destiny upon yourself and bear it, its burden and its greatness. without ever asking what recompense might come from outside. For the creator must be a world for himself and find everything in himself and in Nature to whom he has attached himself.

But perhaps after this descent into yourself and into your inner solitude you will have to give up becoming a poet; (it is enough, as I have said, to feel that one could live without writing: then one must not attempt it at all). But even then this inward searching which I ask of you will not have been in vain. Your life will in any case find its own ways thence, and that they may be good, rich and wide I wish you more than I can say.

What more shall I say to you? Everything seems to me to have its just emphasis: and after all I do only want to advise you to keep gro)Ning quietly and seriously throughout your whole development; you cannot disturb it more rudely than by looking outward and expecting from outside replies to questions that only your inmost feeling in your most hushed hour can perhaps answer.

It was a pleasure to me to find in your letter the name of Professor Horacek: I keep for that lovable and learned man a great veneration and a gratitude that endures through the years. Will you, please, tell him how I feel; it is very good of him still to think of me, and I know how to appreciate it.

The verses which you kindly entrusted to me I am returning at the same time. And I thank you once more for your great and sincere confidence, of which I have tried, through this honest answer given to the best of my knowledge, to make myself a little worthier than, as a stranger, I really am.

Yours faithfully and with all sympathy:

Rainer Maria Rilke

LETTER TWO

Viareggio, near Pisa (!tally),

April 5th, 1903

You must forgive me, my dear sir, for only today gratefully remembering your letter of February 24th: I have been unwell all this time, not exactly ill, but oppressed by an influenza-like lassitude that has made me incapable of anything. And finally, as 1 simply did not get better, I came to this southerly sea, the beneficence of which has helped me once before. But I am not yet well, writing comes hard to me, and so you must take these few lines for more.

Of course you must know that every letter of yours will always give me pleasure, and only bear with the answer which will perhaps often leave you empty-handed; for at bottom, and just in the deepest and most important things, we are unutterably alone, and for one person to be able to advise or even help another, a lot must happen, a lot must go well, a whole constellation of things must come right in order once to succeed.

Today I wanted to tell you just two things more: