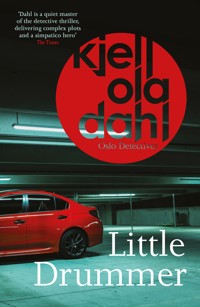

Little Drummer: a nerve-shattering, shocking instalment in the award-winning Oslo Detectives series E-Book

Kjell Ola Dahl

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Godfather of Nordic Noir Kjell Ola Dahl returns with tense, sophisticated, searingly relevant international thriller that explodes the Nordic Noir genre, as Frølich and Gunnarstranda investigate the death of a woman whose scientist boyfriend has also gone missing… 'Dahl is a quiet master of the detective thriller, delivering complex plots and a simpatico hero…' The Times 'If you have never sampled Dahl, now is the time to try' Daily Mail 'Further cements Dahl as the Godfather of Nordic Noir, reminding readers why they fell in love with the genre in the first place' CultureFly ______________ When a woman is found dead in her car in a Norwegian parking garage, everyone suspects an overdose … until a forensics report indicates that she was murdered. Oslo Detectives Frølich and Gunnarstranda discover that the victim's Kenyan scientist boyfriend has disappeared, and their investigations soon lead them into the shady world of international pharmaceutical deals. While Gunnarstranda closes in on the killers in Norway, Frølich and Lise, his new journalist ally, travel to Africa, where they make a series of shocking discoveries about exploitation and corruption in the distribution of foreign aid and essential HIV medications. When tragedy unexpectedly strikes, all three investigators face incalculable danger, spanning two continents. And not everyone will make it out alive… Exploding the confines of the Nordic Noir genre, Little Drummer is a sophisticated, fast-paced, international thriller with a searingly relevant, shocking premise that will keep you glued to the page. ______________ 'A triumph' Denzil Meyrick 'Kjell Ola Dahl's novels are superb. If you haven't read one yet, you need to – right now' William Ryan 'Dark, stylish and suspenseful … the perfect example of why Nordic Noir has become such a popular genre' Reader's Digest 'Kjell Ola Dahl's fine style and intricate plotting are superb. He keeps firm hold of the story, never letting go of the tension' Crime Review WHAT READERS ARE SAYING ***** 'A dark, emotive and twisty mystery' 'Extremely gripping' 'Engrossing and beautifully crafted' 'Fiercely powerful and convincing'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

When a woman is found dead in her car in a Norwegian parking garage, everyone suspects an overdose … until a forensics report indicates that she was murdered. Oslo Detectives Frølich and Gunnarstranda discover that the victim’s Kenyan scientist boyfriend has disappeared, and their investigations soon lead them into the shady world of international pharmaceutical deals.

While Gunnarstranda closes in on the killers in Norway, Frølich and Lise, his new journalist ally, travel to Africa, where they make a series of shocking discoveries about exploitation and corruption in the distribution of foreign aid and essential HIV medications.

When tragedy unexpectedly strikes, all three investigators face incalculable danger, spanning two continents. And not everyone will make it out alive…

Exploding the confines of the Nordic Noir genre, Little Drummer is a sophisticated, fast-paced, international thriller with a searingly relevant, shocking premise that will keep you glued to the page.

LITTLE DRUMMER

KJELL OLA DAHL

Translated by Don Bartlett

CONTENTS

LITTLE DRUMMER

THE CRAB

She stopped the car. At first, they sat in silence, staring across the sea. It was so shiny and still. The glacially polished rockfaces of two huge boulders were mirrored in the water with such sharpness it was almost impossible to see where reality finished and the reflection started.

‘I’ll never get used to this,’ he said.

‘To what?’

‘To nights being so light.’

She opened the door and got out. There wasn’t a soul in sight. Nor a sound to be heard – until he opened his door, stepped out and closed it. She walked ahead, turned off the path and followed a narrow track between the rocks. ‘Short cut,’ she said.

Down by the grass, she flipped off her shoes and continued barefoot. The feeling of dewy grass beneath her feet made her stop for a few seconds, stand with her eyes shut, enjoying the sensation, before she set off at a run across the greensward with her arms outstretched.

He watched her with a smile on his face. ‘Watch out for dog shit,’ he shouted.

She stopped and turned, breathing heavily. ‘Come on.’

He bent down, loosened his shoelaces, took off his shoes and followed her. When she crossed the narrow strip of sand and waded into the water, he paused to roll up his trouser legs. ‘I wish I could go swimming, like you,’ he mumbled.

She held up the hem of her skirt and waded out further until she found a white area of sand among the seaweed. The sea reached above her knees. She stared through the water at the sand. ‘Why can’t you?’

‘Actually, I can’t swim.’

She straightened up and tried to remember what this admission reminded her of. Magnus, she thought. But the image of Magnus had faded. So she began to study Stuart; she knew him better now: the almost feminine curve of his spine; the trousers that seemed too big around his slim waist. The slightly inquisitive, humorous glint in his eye, the smiling lips in his slender but symmetrical face. What he had just told her made him seem more tangible, yet more mysterious.

‘You remind me of my cousin,’ she said, proffering a hand. ‘Come on.’

‘I daren’t.’

They eyed each other. After a while he tossed his head lightly and said, ‘The place we just drove past is the most beautiful in the country.’

‘The folk museum?’

‘The houses are the same as at home.’ He took a hesitant step toward her, raising his arms to keep his balance. ‘Is the log house called an årestue?’

She nodded, but corrected his pronunciation.

He said: ‘In the log house the women were cooking over an open fire, like at home. In the folk museum I saw white pigs in the flesh for the first time. At home we have black pigs. When I was small and saw pictures of white pigs, I thought the connection was obvious.’

‘What connection?’

‘White people have white pigs; black people have black pigs.’

He burst into laughter. It began as a splutter and continued as a long, almost soundless gasp.

She waded in further, leaned forward and, collecting her long hair in one hand, began to search for shells. A flounder shot away; all she saw was a shadow darting across the sand. Tiny bubbles rose from where a crab had buried itself, and she spotted the almost transparent creature sneaking away from her toes. She poked the sand above its air hole. The sand crab appeared, anxiously brandishing its small claws.

She looked up. Something had sparked a little tension between them. In his eyes she read seriousness, anxiety and what she interpreted as passion.

‘There’s something you have to know,’ he whispered in a barely audible voice.

She guessed that he wanted to say something that would change the expression in his eyes and answered: ‘This minute?’

‘I’ve done something wrong,’ he whispered.

‘We’ve got plenty of time,’ she said. ‘The night is long, and everything’s quiet.’

‘But I want to tell you. It’s important.’

‘Not now,’ she breathed, reaching out for his arm. ‘I have to show you something.’ To see the movements of the animals in the sand more easily, she focused on a round stone just under the surface of the sea. She had stood like this many times as a child, and this realisation made her mind go blank for a few seconds.

He waded closer. ‘Show me what?’ The bright morning sun shone from a low angle behind his head, and in the strong light the contours of his body were lost – it was as if the sun had spoken, not him. He took another step and reappeared. The water reached up to his knees. The capillary forces in his trousers slowly drew the water up his legs and turned them from orange to black. Then she saw the little crab again. She grabbed it, hid it in her hand, straightened up and passed him her dripping fist. His fingers gripped her hand and opened it.

‘Holy shit.’

Stuart gave a start as the crab fled into his hand. He lost his footing and lurched into a backward stagger to the shore – completely off balance. And even though he had let go of her hand, she allowed herself to fall with him. The water soaked everything they were wearing in a second. When Stuart began to thrash around, she held his arms. ‘It’s not dangerous,’ she gasped, laughing at the same time. His arms wouldn’t quieten down until she had placed her mouth on his. Then they lay in the sand, in thirty centimetres of water, lips on lips, as the sea became colder and colder, making the outermost layer of their skin beneath their sodden clothing hypersensitive as their bodies touched. And, a little later, when the sun had begun to ascend, they laid their clothes to dry on the smooth rock, two boulders that, between them, formed a cleft so narrow that only wayward rays of sun could find their way down to where she held his black body in hers.

When she finally released his lips, she whispered: ‘Now.’

‘What do you mean, “now”?’

‘Now you can tell me everything.’

PART ONE

THE WOMAN IN THE UNDERGROUND CAR PARK

TRANSFIXED

There were some situations Lise Fagernes hated: entering unfamiliar, enclosed spaces was one of them. It rekindled a feeling she had first experienced when she was eight years old. The children in her street had dug a cave in the huge pile of snow left by the ploughs. It was a long, narrow tunnel, so cramped that the snow pressed against your body as you wriggled through and out the other side. When it was her turn, some boys wanted to have a bit of fun. They had lain on their backs by the opening and kicked it full of compacted snow. That was all she could remember. Just the sense of heart-pounding panic. So, she always went to great lengths to control this panic, to keep it at bay. But fighting panic had become something she loathed. It made her feel weak and pathetic. It made her dread driving down into underground car parks. However, now, as she reached the building, she took a deep breath and braced herself. She came to a halt in front of the barrier, rolled down the window and took the ticket from the machine. She clung to the steering wheel as the barrier opened, and, feeling the sweat break out on her forehead, drove in with the window open, even though she could smell the stale air coming into the car. She breathed through her mouth and automatically switched off the radio when it lost the signal. Only when she had driven down to the lower floor and checked in the mirror that no one was behind her did she make the effort to wind up the window again. It was slow work because all her muscles were tense. She looked up. The digital signs on the ceiling flashed in orange to tell her this level was full and pointed downward.

Where are all the people? There wasn’t a living soul around, only tightly parked rows of empty cars. After manoeuvring her way around the third bend, she slowed down. Please don’t make me drive all the way down. Let there be a space here, right here. But there wasn’t. The arrows continued to flash downward. She was forced to continue, forced to pass car bonnet after car bonnet – another bend, the last, down to the lowest, emptiest level. She depressed the clutch pedal and let the car roll around the bend and down until it stopped on its own. Here, at the back of the dimly lit bottom level there were spaces. For a fraction of a second her mind was blocked: she wanted to turn around, drive back up, into the open air and away. She repressed her desperation and stared out: water was dripping from a vent in the ceiling; immense drops were hitting the windscreen, dissolving and running down to the wiper, obscuring her view with a blur. A flickering neon tube was sending blue and yellow light across the car roofs. The dashboard clock showed 09:52. She had eight minutes to make it to the interview. She reached back to take her mobile from her bag. Ring them and say you’re delayed. No. That would anger the man. A disgruntled interviewee makes for a bad feature. And all because you’re afraid to get out of your car in an empty car park. But why is there no one else here? She rammed the car into gear and manoeuvred her way into the nearest space.

Looking right, into the next car, she was startled to see a woman. The sight gave her such a shock it took her breath away, and she placed a hand on her chest. Relax, it’s only someone sitting in a car. Take it easy. She switched off the engine, turned round and grabbed her bag from the back seat. Fumbled inside until she found her lipstick. She took it out and craned her neck to see her reflection in the mirror, but stiffened when she saw the darkness behind her. What am I expecting to see?

Lise Fagernes breathed in, painted her lips red, checked the result and pressed her lips together as she opened the door and pushed it – a little too far. It hit the other vehicle. She squeezed out and closed the door. The echo resounded around the enormous lower floor. Relax. Once you’re around the bend you’ll see other people. You’ll meet all the others going to the shops or important meetings or… At that moment she thought about the woman in the adjacent car and bent down to look through her car windows into the next vehicle. The woman was still sitting there, her head resting at an unnatural angle.

Her nose and half-open mouth were pressed against the glass, but there was not a drop of condensation. The woman in the car wasn’t breathing.

Lise Fagernes – a full-time employee at Verdens Gang who now had six and a half minutes to make her appointment with the middle-aged social commentator whose career was in such steep decline that he had written a book – felt with every pore of her being what her consciousness would not accept: this person was not alive.

For a second Lise was rooted to the spot. The feeling of panic that she always kept under control finally had the upper hand. It started with this paralysis, which gradually wore off under the pressure of her surroundings: the echo of the underground car park, the vibration of a stray grain of sand knocking against the wall of the ventilation shaft, the hum of the neon tube flashing incessantly above the blue metal door covered in graffiti tags. Lise was alone with a dead body, forced to inhale the nauseous smell of concrete and stale exhaust fumes. As her gaze shifted wildly from car to car, she felt a frosty finger bore between her shoulder blades and into her body, an icy chill that spread down her arms and spine, where the feeling changed and became warm, making a cold sweat break out on her skin. She gasped and instinctively took two to three clumsy steps to the side then, as if in a dream, set off at a run between the rows of cars, terrified, not daring to turn to examine the cause of the terror that was propelling her legs. She passed bumper after bumper, the click-clack of her shoes echoing in her ears, and she cursed her high heels and the ridiculous outfit she was wearing for the interview that would never take place, while her breathing lacerated her lungs, as if with a sharp knife. There wasn’t a soul around, until she turned the bend and saw a young mother unloading a pram from the boot of a Volvo. The sight of this woman, the sight of such harmony, poise and self-assurance, allowed Lise Fagernes to regain her composure. She pulled up at once and stood gasping for breath. Now she knew what she had to do. She took the mobile from her bag and tapped in a number.

She called Verdens Gang. Lise Fagernes was a journalist. What she needed now was a photographer.

LOOKING FOR LEADS

As the woman had neither ID nor any other personal possessions on her, it was down to the senior duty officer at Oslo Crime Squad to start making the necessary enquiries that might establish the identity of the victim. The car she had been found in was apparently owned by a certain Kjetil Sandvik. The duty officer rang Sandvik from his desk. It turned out he was a retired pilot living in Heddal. He was extremely ill at ease at being called by Oslo Police, but was able to inform them that his car was being used by his youngest daughter, Marianne, who was studying literature at Oslo University. He hadn’t driven the car himself for more than a year.

While Sandvik was talking, the duty officer tapped his forefinger on a biro, the rounded end of which he had placed in his left nostril. This was a habit he had developed when he was on the phone and no longer listening. What he really wanted to do was hang up. However, this conversation had put him in a difficult position. From the police report, it emerged that the car park staff had called the police, who in turn had called A&E. The doctor who arrived with the paramedics in the ambulance concluded that the woman’s death had been caused by a self-administered dose of heroin and had issued a death certificate to this effect. Between the fingers of the victim hung a syringe, pointing down to the floor, where the duty officer had found the rest of the junkie’s standard kit: a spoon, a cigarette lighter and some silver paper containing traces of heroin.

It was, therefore, highly probable that the deceased was the car-owner’s daughter. But it wasn’t certain. And it was the job of a priest or someone suitably qualified to pass on the sad tidings, not the lot of an impatient policeman like himself. Having no wish to get himself into deep water, he stammered out an apology for ringing Sandvik, knowing full well that this would not put the car-owner’s mind at rest. He failed to ask Sandvik about his daughter’s appearance or her use of drugs. Instead, he made out that his call was due to a parking issue, which in a sense was true, as the car was at that moment being towed out of the underground car park and taken to Oslo Council’s impoundment lot for illegally parked vehicles in the district of Sogn.

After the conversation, his sense of unease developed into annoyance, and he soon knew what he would do. For some time now, he’d had a bone to pick with a certain police inspector, and because he had just received another complaint regarding the man’s wilful smoking habits, he decided to let the man – Inspector Gunnarstranda – sharpen his wits for a few hours on a bog-standard OD case.

As the duty officer marched into the office shortly afterwards, Gunnarstranda was fighting to stifle an unpleasant coughing fit. These bouts were getting worse and worse. If he let them have free rein, he would end up choking, which would finish him off entirely. And he didn’t want to give anyone the pleasure of that sight, least of all the man towering over his desk right now: the kind of guy who only articulated his thoughts as he spoke them, and for that reason repeated every sentence aloud, as if to confirm to himself what he had been thinking and saying.

Gunnarstranda observed him in silence.

After a while, the ploy started working. At first, the man stopped talking. Then he began to scratch his groin. When Gunnarstranda went to shake hands, the man put down the papers as meekly as a teenager handing over a poor school report.

Gunnarstranda waited until he was alone in the office before he began to read. Afterwards he mused for a few moments, then picked up the phone.

The deceased still hadn’t been identified. If the woman belonged to the drugs fraternity around the Plaza Hotel or Oslo Central Station, her name would already have come up, because she would be an ‘old friend’ of the police and the paramedics. The equipment in the car suggested she was a junkie. And Gunnarstranda didn’t want to dispute the doctor’s conclusion about the cause of death. But if his superior officer had decided to delegate this job to him Gunnarstranda would have come up with several possible interpretations. One was that the death may be suspicious.

He phoned the Forensic Institute and commissioned an autopsy of the body. The use of sorely needed funds for the autopsy of a typical OD case would irritate both his boss, the budget holder, and the man who had just left him. But it was probably the latter who would be left holding the baby. The satisfaction of paying a senior officer back for a deliberate slight and also precipitating a row between two people who occasionally riled him put him in such a good mood that he determined at once to do some field work and clarify the identity of the victim.

The car-owner’s daughter lived in Bjerregårds gate, in one of the brick tenement buildings by the Maridalsveien intersection. There was a smell of frying in the stairwell and a blue cardboard disc on the door. Two names, Marianne Sandvik and Kristine Ramm, were written in red.

The door was opened by an overweight blonde in her early twenties. She wore a sweet, heavy perfume. Her hair was on the thin side, and she had broad features with a prominent chin, which lent her a friendly but also anonymous appearance.

‘Are you Marianne Sandvik?’ the inspector asked after introducing himself.

‘Yes, I am.’

‘Are you in possession of a Honda Civic?’

‘Yes.’ The expression of mild curiosity that had hitherto characterised her broad face gave way to a trace of anxiety.

‘Is it missing?’

‘Not as far as I know. From here, in the stairwell.’

When the policeman didn’t react to her tone but continued to look at her with a blank expression, she added: ‘Have I parked illegally?’

When the policeman still didn’t say anything, she continued nervously: ‘It’s usually parked a bit further up Bjerregårds gate…’

‘It’s not there now.’

The woman’s face began to colour. ‘Ah,’ she said with a brief, strained laugh. ‘Kristine must’ve taken it. You see, we share the car. But as you’re the police, perhaps I can guess what’s happened. Has it been stolen?’

‘Kristine who?’

‘Kristine who lives here.’ She pointed to the blue disc and the name of Kristine Ramm.

‘Have you got any ID?’

Marianne Sandvik hesitated for a few seconds before turning and going inside. Gunnarstranda followed her in as though it were the most natural thing in the world. The flat was bright and inviting. It smelt of boiled eggs and fresh rolls. There were the remains of a half-eaten meal on the table. The sunlight from the windows filtered through the leaves of a ficus plant in a pot and gently cast its rays over some posters on the wall. One, of a dance at Smuget, showed the backlit silhouette of a female body. Next to it, Audrey Hepburn posed between Bogart and Holden, both wearing dinner jackets. The last poster showed Elvis Presley in a white, fringed jumpsuit. When Marianne Sandvik went through a bedroom door, Gunnarstranda opened another door leading out of the lounge. He entered a tidy bedroom. A few textbooks and notepads on the desk revealed that this room belonged to Kristine Ramm.

When Marianne Sandvik appeared in the doorway Gunnarstranda was lying flat on the floor beside the bed, stretching one arm under it as far as he could.

‘What are you doing?’ she asked in dismay, as the inspector’s glasses slid up onto his forehead, undoing his carefully arranged comb-over. He squeezed his eyes tight until, with a groan, he reached what he was after. Standing up, he shook open a plastic bag and dropped a Nokia phone inside. Then he brushed some dust balls off his jacket sleeve, while Marianne regarded him sceptically from the door and the traffic in Maridalsveien droned past.

‘It must’ve slipped down the crack between the mattress and the wall,’ he concluded, studying Marianne’s ID and confirming that she was who she claimed to be. ‘Thank you,’ he said, and passed her driving licence back. ‘Have you got a photo of Kristine?’

‘If you come with me.’

She rummaged through some drawers in a long bench placed against a wall in the lounge. At length, she produced a photograph of a smiling woman sitting on a sofa. The flash had lit up both retinas, turning them red. People shouldn’t smile at photographers, Gunnarstranda thought. Smiling faces expressed nothing more than the smile, not the appearance. ‘Can you describe her?’ He could read from Marianne’s expression that she was beginning to put two and two together. As her suspicions of the gravity of the situation slowly dispelled her initial nervousness, she became more distant. The flush had changed to two pink spots on her cheeks. She stepped forward and glanced down at the photograph to describe the features in more detail: ‘Kristine has dark hair, shoulder length. She’s quite slim and, well, about the same height as me. One seventy two.’

‘Brown or blue eyes?’

‘Blue.’

Gunnarstranda slipped the photograph into his inside pocket and asked: ‘Has Kristine ever taken drugs? Heroin, recreational drugs, amphetamines?’

‘No, are you crazy? No, she hasn’t.’

‘Sure?’

‘Absolutely.’

Gunnarstranda eyed her suspiciously.

‘A hundred per cent,’ Marianne Sandvik said.

‘What about alcohol?’

‘She drinks beer and wine, like everyone else.’

‘A lot?’

‘No, the usual, at parties. Why can’t you tell me honestly and directly what this is about?’

‘Has she been hanging out with any dubious types recently?’

‘Not as far as I know, no.’

‘When was the last time you saw her?’

‘Yesterday morning.’

‘When?’

‘At about six, half seven, in the morning. We met in the hall here. I was just back from a late-nighter. She was also arriving back from some party or other. Her hair was wet. She’d been in the sea.’

‘At six o’clock on a Sunday morning?’

‘Yes – I asked her. “Have you been swimming?” I said, and she replied, “Yes, in Huk.” “Alone?” I asked. “No,” she said. “Who was he?” I said. “Wouldn’t you like to know?” she said. And she laughed. She seemed to be in love.’

‘How do you mean “in love”?’

‘She was a bit hyped up, in a good mood. My impression was that she was talking about a guy she’d met and the emotions were flowing.’

‘Did she say the man’s name?’

‘No, that was the end of the conversation. She went into the shower. I sat down and had a smoke. Afterwards I went to bed. I could hear that she did the same.’

‘Do you know what she was doing the previous evening? On Saturday?’

‘’Fraid not. I was away all last week, so we haven’t talked much recently.’

‘And how late did you sleep – on the Sunday?’

‘Erm, now you’re asking. I went to work at four. I must’ve eaten a bit first. I’m a waitress at the Lekteren in Aker Brygge.’

‘Was Kristine here when you woke up?’

‘No, she’d gone out.’

‘How long were you at work?’

‘Until twelve, midnight.’

‘And then?’

‘Then Knut picked me up. We went back to his place. And I stayed over until today.’

‘Knut?’

‘Boyfriend. He works for Storebrand. Knut Radér.’

‘Do you know what Kristine did after she came home yesterday morning?’

‘I’d guess she had a sleep. But I’m getting quite curious now as to what this is about.’

‘Do you know if Kristine has had any problems recently?’

‘Such as what?’

‘A death in the family, romantic problems, bad grades at university or general depression…’

‘No, not that I know of.’

‘Would you say you’re close?’

‘Yes, as close as…’

‘What does she live off?’

‘She’s a student, like me, and works a bit on the side.’

‘What’s she studying?’

‘Folklore studies and social anthropology. She’s going to major in social anthropology.’

‘Where does she work?’

‘In a bar, a sort of pub, not far from Bankplassen. I think it’s called Joyce or Voice, or something like that.’

The policeman angled his head as he made notes. ‘Have you known her for many years?’

‘No, we got to know each other here.’

‘Here?’

‘This is my flat, but it’s expensive, and as there are two bedrooms I put some ads up at Blindern University, in the café, to find someone to share the costs with me. A few girls phoned. I chose Kristine because we got on well. Same wavelength.’

‘A long time ago?’

‘Soon be a year.’

‘Do you know her well?’

‘So so. It’s always good to have a little distance from the people you live with. We agree on that. That’s one of the reasons I chose her.’

‘You’re not on very close terms then?’

Marianne Sandvik took a deep breath: ‘This would be easier if you were more open about why—’

‘How close?’ the policeman interrupted.

‘A little. Not very, I suppose.’

‘Not close enough for her to reveal the name of the man she’d been with the other night?’

‘She would probably have told me eventually if I’d pushed, but I don’t do that. And that should tell you something about how close we are.’

‘Where’s she from?’

‘Molde. Somewhere just outside. Near Hustadvika. Bud, I think the place is called.’

‘Has she been in Oslo long?’

‘Can’t tell you, but I think she moved here because of her studies.’

‘What sort of people does she hang around with?’

‘All sorts. Students, people she knows from Vestland.’

‘Has she got any brothers or sisters?’

‘She’s an only child. I think her parents are divorced. Her father works on oil rigs. In the North Sea. I don’t know anything about her mother.’

‘This Honda’s actually owned by your father, isn’t it? Does anyone else apart from you and Kristine use it?’

‘No.’

Gunnarstranda considered what to do. ‘I’d like you to come with me for an hour or so,’ he said at last.

She frowned hesitantly. ‘Where to?’

‘The Forensic Institute.’

After a shaken Marianne Sandvik had confirmed that the deceased was Kristine Ramm, Gunnarstranda drove her home. And once he was finally back in the office, his next job was to ensure that the priest in the parish where the woman’s relatives resided was instructed to inform them of her death. He found the telephone number of the appropriate police station and by chance talked to an officer who vaguely knew the family. The man was able to tell him that Kristine Ramm’s mother was divorced and had reverted to her maiden name. She was on her own and receiving benefits.

Gunnarstranda told the officer Kristine Ramm probably died of self-administered heroin poisoning, but there would be an autopsy anyway.

After ringing off, he had actually nothing left to do. At first, he sat staring at the wall, then he glanced down at the mobile phone he had found in the woman’s bedsit. And without considering what he was doing, he began to fiddle with it.

ORBIT

Hanging tremulously over Nesoddland peninsula, the sun made the sea resemble a tray covered with crinkly gilt paper. Frank Frølich squinted through his dark glasses at a bottle of water. In it, he saw the sun reflected like the head of a yellow clout nail.

He sat with his face turned to the people streaming up and down the waterfront promenade in Aker Brygge and reluctantly had to confess that he was somewhat indifferent to whatever undiscovered beauties there might be in the crowds. Instead, he caught himself craning his head at the sight of long, black hair falling in a particular way or felt his stomach flutter when he saw a dark-haired, long-legged woman in the queue by the ice-cream kiosk. His unease would become so acute that he was half tempted to stand up and walk past, glancing over his shoulder to make sure, to find out if it really was Anna standing there, to quieten his unease – until it dissipated of its own accord because the person changed posture in a sudden fit of boredom and revealed that she was someone else. What the hell am I doing? he thought; this was like the time he had rung her at home and, sweating profusely, spluttered out some ridiculous excuse, before engaging in a bizarre conversation.

When he spotted Gunnarstranda walking up the jetty he was thinking about Anna’s eyebrows. They were like two perfectly silhouetted wings of a bird. This image melted away as Gunnarstranda’s pale, creased, balding head filled his field of vision. To celebrate the glorious day, his eyes were obscured by a pair of sunglasses that any artist or teenager hunting for cult objets d’art would have paid a fortune for. The glasses were large and shaped like raindrops, reflecting in them colours ranging from black to mauve to light-blue, in a gilt plastic frame.

‘How much do you want for them?’ Frølich asked.

‘For what?’ Gunnarstranda said, casting around for a free chair. He found one at an adjacent table and took it without hesitation. The two women sitting at the table exchanged astonished expressions at the man’s impudence. ‘It’s taken. We’re waiting for someone,’ one of them blurted.

‘For your sunglasses,’ Frølich said, knowing that Gunnarstranda was deaf to that kind of objection. ‘They must be at least fifty years old.’

‘Twenty-five.’ Gunnarstranda sat down and placed a newspaper on the table. ‘I bought them at an Esso garage. Easter of 1977. In Fagernes. Let me show you something.’

Frank Frølich watched two pairs of broad hips and two erect necks stand up and move. The two women found another table further away and glared furiously at himself and Gunnarstranda, who was now opening today’s Dagbladet. He licked his forefinger and flicked painstakingly through the newspaper, page by page, until he found the right place and pointed to an article. Frølich leaned over and skimmed through it. He had read the same report in the previous day’s evening edition of Aftenposten. A foreigner had been reported missing, for three days.

The waitress, a well-rounded young woman with her hair gathered in a ponytail, came to their table. ‘Ah, it’s you,’ Gunnarstranda said in a friendly voice. ‘How’s it going?’

‘So so,’ she said.

Gunnarstranda removed his glasses and asked for a large beer. He glanced at Frølich, who shook his head and pointed to his mineral water.

When the waitress ambled off, Gunnarstranda pointed down to the newspaper and said: ‘How about us two looking for this missing man?’

‘An asylum seeker on the run?’

Gunnarstranda stood up and scanned the waterfront. Soon he was waving to a familiar figure in the crowd: Emil Yttergjerde, who was strolling muscularly down the quayside toward them.

‘He’s not on the run. He’s a respected scientist.’

Emil Yttergjerde was wearing tight jeans and a bicep-flaunting white T-shirt. His head was shaven and he had organised his sparse stubble into a pointed extension of his chin. Before going to find a chair, he announced in a loud voice that he always sat with his back to the ostentatious buildings in Aker Brygge.

Frølich studied the glittering surface of the water while waiting for Yttergjerde to finish.

‘Swindlers and packs of thieves, the whole lot of them. We invest all our energy into building a case against them and then they delay it by…’

Frølich wished he would lower his voice.

‘We should be living in the Middle Ages,’ Yttergjerde waffled on, wriggling on his chair. ‘They knew what to do. If some bigshot got up to any knavery, they’d whack him on the noggin and cut off his bollocks. Afterwards he had to play the jester in front of the finer folk. If he was funny, they threw him peanuts and patted him on the head.’

Gunnarstranda stared at him with a deep frown. ‘Where have you heard that?’

‘I’ve seen it on TV. Besides, it’s true. They used these bastards instead of monkeys. And if that didn’t work, they just cut off their heads. Simple as that.’ Yttergjerde pulled at his fingers, one by one, until they cracked.

‘Tell Frølich about Takeyo,’ Gunnarstranda said impatiently.

‘The guy’s twenty-seven and is working on some kind of doctorate. He’s from Kenya and has come to Norway via some aid project in Uganda. He studied at the University of Kampala, which is the capital. That’s all we have in the reports. The details are a bit unclear, but he was reported missing by two different women. One’s called Ingunn Løvseth. She works with Takeyo at the university. But by the time she’d pulled her finger out, a woman called Evelyn Sømme had already rung the station. Apparently she’s known this guy ever since he was small, and they were supposed to be going out to eat on Monday. But he never showed up.’

While Yttergjerde was talking, Gunnarstranda had rolled a cigarette. He lit up, took a speculative puff and turned to Frølich, who asked:

‘Why are you interested?’

‘Several reasons. One is that the man will soon have been missing for four days.’

Gunnarstranda leaned back as the waitress placed a tray of foaming beer glasses on the table. He waited until the waitress had gone before continuing: ‘She…’ He nodded in the direction of the waitress. ‘She and I talked on Monday. She shared a flat with the girl who OD’ed in the car park on Ibsenringen.’ He produced a phone from his pocket and laid it on the table. ‘This phone belongs to the dead woman, Kristine Ramm. She used it to call Takeyo’s home number five times on the day she died. The same day he disappeared.’

‘Tragic,’ Yttergjerde said. ‘When did she die?’

‘On Sunday, the fourth of August.’

‘That was the boiling-hot day I went swimming in Svartkulp,’ Yttergjerde said.

Frølich frowned. ‘Svartkulp?’

‘Sorry,’ Yttergjerde said, self-consciously. ‘I meant Lake Sognsvann.’

‘At 21:05 she rang Takeyo for the last time.’

‘Jesus,’ Yttergjerde interrupted. ‘I meant Lake—’

Gunnarstranda cut him short with a raised hand. ‘The day after, so Monday the fifth, Stuart Takeyo didn’t turn up for work. And, so far, he’s been missing for four days. Before disappearing, he was contacted by this woman, who later died of an overdose.’

‘A narco case,’ Frølich said.

‘Exactly. And I was delegated to clear it up: to find out who snuffed it after a jab in the arm. And then down from the sky flutters a missing-person case, an African who this young lady calls again and again before departing this world. And in her circle of friends everyone gapes because no one has any knowledge of her doing drugs. She was as clean as a whistle – and the person who most probably sold her the heroin has conveniently vanished.’

‘No parents believe their children are on drugs until the shit hits the fan and there they are.’

‘I’ve never ever been near Svartkulp,’ Yttergjerde insisted.

Gunnarstranda sent him a stern glare.

‘It’s just that—’

‘You’ve made your point, Yttergjerde. Thank you for your input.’ Gunnarstranda turned to Frølich. ‘I’m going to check out Takeyo’s flat right now.’

‘Now?’

‘Well, as soon as possible.’

‘Who’s driving?’

‘You are,’ Gunnarstranda said, sipping his beer. ‘Because you haven’t been drinking.’

‘What do you reckon about Yttergjerde?’ Frølich asked as they drove out of the roundabout by Bislett and up Theresegate. ‘Is he a closet gay?’

‘Why does it interest you?’

‘The slip of the tongue. He said he’d been swimming in Svartgulp. That’s a gay cruising ground.’

Gunnarstranda shrugged. ‘It’s so modern now to be gay. It’ll soon be as normal as going on a demo. First it was in to be anti whale-catching. Then they marched against police violence. Before you know what’s going on, we’ll have to look to women for our protection. Here,’ he said, pointing to a free parking space beside a black Saab. They got out. There was no one around.

Shortly afterwards, a dark Passat passed them. The driver waved, continued to the block of flats and parked as if he lived there. The taxi sign on the roof was extinguished. The man who struggled out of the driver’s seat had once had curls. A long time ago. The remaining hair clung to his scalp like cotton wool. It was as though someone was holding an invisible vacuum cleaner over his head. He was broad in the beam, and his ears stuck out like tuba mouthpieces on either side. Introducing himself as Jon Legreid, he brandished a huge bunch of keys in front of him, then waddled ahead to the front entrance at the corner of the block.

Gunnarstranda had a choking fit on the way up the stairs and hung back.

Legreid spent a long time over unhooking a smaller keyring from the main bunch and opening the flat door. ‘You can keep the keys,’ he mumbled. ‘Pop them into the post box on your way out. It’s got “Legreid” written on the front.’

‘Is the furniture the tenant’s?’ Gunnarstranda asked, taking the keys, still panting.

‘It’s all mine,’ Legreid said. ‘I let the flat furnished; that’s what it says quite clearly in the contract.’

Gunnarstranda absent-mindedly arranged his own hair before entering. The flat smelt stale and fusty. The hallway was long and narrow. The plaster walls were still unpainted, which didn’t improve the impression. Apart from the hallway and the bathroom, the flat consisted of one large room with a sink, a stove, a sofa bed and a desk.

Gunnarstranda opened a window. A tram screeched to a halt at the stop outside. ‘No fridge?’ He glanced over to the owner, who was still standing in the doorway. ‘There must be food rotting in here. You, as the owner, should consider the danger of rats.’

Legreid shouted: ‘Anything else? I don’t have time to stand around.’

‘When did you last see the tenant?’

‘Not since we signed the contract.’

‘And when was that?

‘Before Christmas last year.’

‘How do you get the rent?’

‘Bank transfer. No hassle with the guy. Pays on time every month.’

‘And otherwise? Comments, complaints?’

‘Not a squeak.’

Legreid left.

‘If there’s any smack in this place, we’ll find it.’ Gunnarstranda put on plastic gloves.

The computer was an older model. Dust had collected around the tower and the screen. Gunnarstranda opened the desk drawers. They were empty apart from a stack of biros and a ruler. He slammed the last drawer shut. There was nothing attached under the desktop. On top, there was a scientific journal, beneath which was an edition of Playboy.

Inside the magazine was a NOR bank card with the Visa logo on one side and a photograph of Stuart Takeyo on the other. The picture had been taken in a booth and was not very sharp; it gave them little information about his appearance except that he was young, had regular features, a narrow chin and very short hair. The man’s eyes were half closed, which lent him a lethargic appearance. The card was valid until November.

‘Vegetables, fruit and ham.’ Frølich lifted a plastic bag with the contents almost liquid now and held his nose.

Gunnarstranda waved the bank card.

Frølich went over and studied the Playboy article. The glossy pages showed a big picture of black men cleaning fishing nets on a white sandy beach and smiling. It was an article about nature and fishing.

Gunnarstranda went over to the bookshelves, and examined the books and what was between and behind them. On one shelf there were some sheets of paper. Compactly penned notes in neat, elegant handwriting. Gunnarstranda stuffed all of them into a carrier bag. Afterwards he went to the wardrobe. There were three shirts hanging inside, all brightly coloured. The suit jacket had worn sleeves. On the floor were two pairs of shoes. Gunnarstranda lifted them to see what size they were. ‘What do you think?’

‘Forty-three or forty-four,’ Frølich said, busy with the kitchen cupboards.

Gunnarstranda read the label: ‘Bata,’ he muttered.

‘Look at the soles,’ Frølich said. ‘Cheap plastic. No support in the sole. This man’s not exactly well off. Look here.’ He took out an empty nylon travel bag with the destination label still tied around one handle. ‘Travelling without a bank card and a bag?’

Gunnarstranda continued into the little bathroom, where he examined the classic hiding places: the toilet cistern, under the bathtub, behind the sink and the trap underneath. It was beginning to stink of putrid water. On the sink was a toothbrush and a well-used bar of soap. On a shelf under a medicine cabinet containing a packet of plasters were a razor and a tube of shaving cream.

‘This guy’s planning to return at some point,’ Frølich said from the doorway. ‘He didn’t take his clothes, bank card or toiletries.’

Gunnarstranda returned to the main room and inspected the sofa bed. Frølich helped him to lift the mattress. Underneath was a green passport issued in the name of Stuart Takeyo, and the ID photograph was the same as on the bank card.

Frølich scrutinised the seams of the mattress in case something had been sewn inside.

Gunnarstranda pointed to the telephone on the bedside table. ‘Is that a red light I can see?’

‘The answer machine.’ Frølich went over and took out the little tape. He pressed a button. Immediately there was a scratchy message coming from the loudspeaker.

‘…This is Stuart speaking. Please leave a message…’

A loud peep was heard before the tape wound scratchily on: ‘Hi. It’s me again. Where are you? I don’t want to do this alone. Not now. Please hurry…’

The scratching continued and then went silent. Then there were several calls, but each time the connection was broken without a word being said. It happened six times. The seventh and last time was a familiar cough.

‘That was me,’ Gunnarstranda said. ‘Play the tape again.’

Frølich rewound, the scratching noise repeated itself and the same woman’s voice spoke via the loudspeaker.

‘She must’ve rung before. And that time they must’ve spoken.’

‘They’ve arranged to meet,’ Frølich said. ‘But after he’s left she’s become impatient and rings again. And there must’ve been something new. “Not now”. Something has happened.’

‘It could be something to do with her. We don’t even know if it’s Kristine Ramm talking. But bring the tape. Marianne Sandvik will tell us if it’s Kristine’s voice.

After sealing the door to the flat and trudging down the stairs, they stopped in front of a line of post boxes. On the left, at the bottom, there was a dented post box with Takeyo’s name on it. Gunnarstranda fumbled with the bunch of keys until he found one to fit. The box was half full. Among the advertising there were a few bills, but there was only one letter. Stuart Takeyo’s name and address were typewritten on the envelope. The two officers exchanged looks. Gunnarstranda, who was still wearing plastic gloves, took a penknife from his pocket. Without the slightest embarrassment, he cut open the envelope. There was a single sheet inside – a computer print-out. There were only five words, written in Courier and block capitals. The message was concise and left no room for misunderstanding:

YOU’RE A DEAD MAN, NIGGER!

BREATHING DIFFICULTIES

She told him to strip to the waist. Gunnarstranda turned to the mirror and obeyed with a grim expression. He didn’t like undressing in front of a mirror. It was bad enough undressing in front of a woman without having to witness it himself. Pensive, he stood for a few seconds viewing his lean upper body before turning to her.