9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

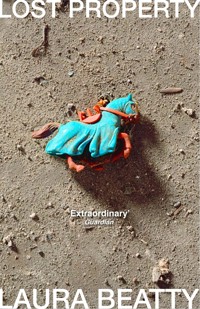

'Clever, brave and urgent. I thought about Lost Property for days after I finished it.' Sarah Moss, author of Ghost Wall 'Fascinating and eloquent discussion of nationalism, art and conflict, leavened with wry humour.' Mail on Sunday ____________________ In the middle of her life, a writer finds herself in a dark wood, despairing at how modern Britain has become a place of such greed and indifference. In an attempt to understand her country and her species, she and her lover rent a busted-out van and journey through France and down to the Mediterranean, across Italy and the Balkans, finishing in Greece and its islands. Along the way, they drive through the Norman Conquest, the Hundred Years War, the Italian Renaissance, the 1990s and on to the current refugee crisis, encountering the shades of history, sometimes figuratively and sometimes - such as Joan of Arc, sitting pertly in the back of the van - quite literally. As she roadtrips through 10,000 years of civilization, watching humanity repeat itself with wars over borderlines and exceed itself with the creation of timeless art, the writer begins to reckon with the very worst and the very best in our collective natures - and it is in seeing the beauty beside the ugliness, the light among the trees, that she begins to see, finally, a way for her to go home.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

LOST PROPERTY

Also by Laura Beatty

Fiction

PollardDarkling

Non-fiction

Lillie Langtry: Manner, Masks and MoralsAnne Boleyn: The Wife Who Lost Her Head

Lost Property

Laura Beatty

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 byAtlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Laura Beatty, 2019

The moral right of Laura Beatty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The picture acknowledgements on p. 265 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 738 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 739 0

Printed in XXXX

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

‘The brain is a metaphor of the world…[It] can be seen as something like a huge country:as a nested structure, of villages and towns, thendistricts, gathered into countries, regions and evenpartly autonomous states or lands.’

The Master and his Emissary, Iain McGilchrist

‘The Russia of our books and kitchens never existed.It was all in our heads.’

Second-Hand Time, Svetlana Alexievich

Before

At the midpoint of my life, I found myself in a dark wood.

Dark as a blanket.

I think, I did not want this.

The woman who lounges on a nearby step as if on a sofa, her carrier bags bunched round her like scatter cushions, looks up as I pass and says with surprising lucidity, ‘I can relate to that.’

She is always here. I have often hurriedly, as if doing something I shouldn’t, dropped a few coins in her cup but without eye contact. Once, in the early days, I did greet her. She looked so familiar. She looked like someone from a book I once wrote. It doesn’t matter whether she is or not. Books are not real. But still, I thought, she looks unsettlingly familiar.

‘Do I know you?’ I asked, stepping into the fog of her smell. I clattered my coins in her cup and she sparked a lighter and held it up in response, its flame almost touching my nose. She opened her mouth, with its dark interior and its teeth like solitaire pegs. She said something incoherent about waves and slaves and her voice was grating and several passers-by stopped to watch. I turned quickly away. Their attention made me somehow complicit and I didn’t want that. I must have been mistaken. I didn’t know her after all. Of course I didn’t; a bag-lady, out on a doorstep.

‘Never. Never Ne-ver,’ she shouted behind me, as I scuttled away, head down.

I haven’t addressed her since. I hurry past, trying not to look. But out of the corner of my eye, last week, I noticed she now has a little sign, propped up like a birthday card in front of her. It says ‘BritAnnia’ in wonky writing.

Day after day, like everyone else, I pass with my head turned away; all these people heaped like trash on the streets of our cities with their bags and their lighters and their various sad and private madness, we just pretend they don’t exist. But she is hard to ignore. She is always there. And now today, wearing something on her head like an upturned coal-scuttle, she has a road-sweeper’s broom in her hand and for a moment she is lucid. It is the lucidity, not the fancy dress, that makes me stop a second time.

Then, because I am looking, I read the names on her bags. Oh, I wish I hadn’t done that. They say Boots and Boots and Mothercare. Mothercare, Mothercare, Boots, just as I once wrote when I first started out, when I invented my Anne, my Everyman.

You what?

I steady myself with one hand against the wall. The woman on the step: did I, or didn’t I make all this up? I mean, am I in my head, or out of it? We need to sort this out. Because we’ve made so many copies of life, all meant to be useful. We’ve written so many books and drawn so many pictures and made so many films and taken so many photographs that we’ve got confused. I can’t tell any more what’s true and what’s not. Where exactly is it we are all living?

I check no one is looking and lean in to ask her, ‘Look, who are you and what exactly are you doing?’

‘BritAnnia!’ she says, hissing through the solitaire pegs.

I put my face in close. ‘You’re not Britannia,’ I hiss back. ‘You are plain Anne. I know. I made you up.’

Maybe her condition is catching.

‘That’s enough,’ my rational self says to my other, my heart panicking into close quiet. But I don’t know now whether she is herself, or just more me. At the midpoint of my life. Out in the street on the way to the shop to buy something as innocent as milk. Dark as a blanket.

I go on again, as if with purpose but it’s lonely not knowing. ‘Hello?’ I put my hand out unsteadily, as if hoping for a rail. I need to sit down for a minute. ‘Can anyone see a step?’ I think I need a guide. I look round for the little flare of BritAnnia’s lighter. ‘Show me a light, can’t you? I know you’ve got one.’

‘Hello?’ Into the darkness. ‘Hello? Is anybody there?’ And while I wait for an answer, I stand still.

Where am I? Because I can’t see. The dark is crowding at me now. Is it universal – this dark – or just mine? Have you noticed? I stand still and I look up and, looking up, I find trees – are they trees? Or are they tower blocks, the light only barely making it through – hemming me in, pushing skywards, casting their obliterating shadow. No air to breathe, no light. This savage city – or is it a forest? – that we have wandered into by mistake. This make-or-break place of wolves and cut-throats. So the stories are true, or have taken over, because this is how it happens. This is how you get lost. Where the shit is the path? You know, the path we were all on together? I thought we were in this together. Because the path was so clear when we set off – remember? – when we made our promises and took our places and set things up for life, booming with confidence in the thoughtless certainty of morning.

Idiots.

Nothing in response. Just the rustle of paper blowing, or leaves, a noise so small I might have imagined it, just something dropping unnoticed to the floor. I hold my hand out in front of me, my writing hand. It is dimly visible – as, at my feet, are birds: pigeons, hobbling, and little, brittle, fume-caked sparrows. All of these seem solid.

Is my writing hand to blame? Because this is a place I didn’t intend. I thought writing was there to throw light on the way we are, so that the way we are could change. But the change hasn’t happened, or something else has taken over, because look, our dystopias seem to be coming true and now our eyes are too tired, or too dark with imagined disaster, to protest. ‘Yes,’ we say sagely, with told-you-so voices, ‘we knew it would be like this.’

‘Keep going,’ tradition booms, or is it only the blood in our own ears? ‘Push on. Put your best foot forward.’ Tradition always speaks in clichés. ‘Don’t rock the boat,’ it says. ‘Chin up. Keep moving.’

‘But which way?’ you scream into the shut mouth of the wood, or the city. ‘Which way? I have children to think of. Quick, we are desperate.’ Forward or back? To the Left? Or Right? All look equally wrong. Things are worsening so fast and I really don’t think there is time.

Now there is only a crawling, bent-double passageway anywhere you look: under things, over things, rotten logs – or are they really people? Is this a wood or not? Everything has gone feral. Sour buddleia growing in cracks. There are drains and bogs and sump-holes you could break an ankle in. We’ve been over it all before. It’s all so fucking wearisome.

Luckily we are a resilient and hopeful species. We don’t give up, thinking it out till the last – you too – trying a new angle, speeding up brightly along what looks like a possible pathway. Somewhere there are settled people who function thoughtfully together. I am sure of it.

Somewhere there are societies where the world and its image communicate usefully; where the image’s authority is only borrowed because the world is still solid and pre-eminent, and where real things don’t get stared through or denied just because we have addressed the reality of their problems in our imaginations.

But the track that looked so promising founders again, in the quiet. Just the sound of your own breath faster and faster, and your own shuffling footfall among these mouldering generations of litter, of wrappers, of leaves. It’s so dark. We’re lost. This time I think we are really lost.

Tradition is dumb. It assumes progress is linear. It takes no account of the fact that life is full of spirals and arcs. Circles exist as a definite possibility. We might, if we aren’t careful, make a wide parabola, skirting the edge of whatever this is and turning inwards again, away from the light. We learn nothing, as it turns out, from books, from history, from thought, or from art. After all this time, it is possible that out of exhaustion and disillusionment we might just give up. We might just end up sitting down on a log, or a person, in the unending filthy shadow, in this tacit submission of all things to forgetting, ignoring the warnings of what happened before. We might just shrug and let ourselves be consumed by stillness till we crumble and sift down, to be scurried over by those mice that appear so dangerously on the rails when you wait for the Underground. If we don’t fight, it is possible that we might never come out again.

‘So are you saying we should fight?’ my one self says to my other, desperate enough for anything. Turning my head back and forth, straining for advice. ‘Is that what you advise?’ Because it’s true, there is always revolt, both private and public. You can take up an axe, you can hack yourself a clear-way back to the sea. That at least would be energetic. It would be something to do, other than talk, and blood-letting can be cathartic.

Hesitating in the moment of decision, because revolt has its own life and you have to have the stomach for it; revolt turns things so that the earth replaces the sky. We know this. We cut our own king’s head off once upon a time. It’s hard not to get lost inside violence. It will push itself up, blooming like a giant mushroom, bigger, deadlier than we could ever remember, or ever have imagined. It will topple the trees – or the towers, it doesn’t care which – while the people who released it cry and run for cover. It will grow until its canopy, just like the wood in the first place, umbrellas itself above our heads, and our sky, from horizon to horizon, is just gills the colour of decay.

As the trees come skittling down – as the sky mushrooms and darkens and the bedrock is revealed – what do you suggest that we do?

I SAID, WHAT DO YOU SUGGEST WE SHOULD DO?

God has gone very quiet.

1

Let’s start again, more calmly.

In the world of poems or stories intractable problems find their solutions in some sideways step to a parallel reality, a place that is elsewhere but companionably alongside. Think of Dante and Gulliver and Gilgamesh. Think of the fairy tales you were told as a child. You take a journey by foot or ship, or you open a door in a wardrobe, or you take the proffered magic cloak, or the proffered hand of Virgil. Whichever way it is, you slip round the back of the wind, or down through the circles of Hell, and if you pay attention, and you don’t drop it or give it accidentally away, you come out holding the answer. Often the answer you hold is simply acceptance. So you could say there aren’t any answers. There isn’t even understanding a lot of the time, but still parallels can be a comfort – they offer connection between things that will always be separate and they allow, in fact they thrive on, difference. That used to be the point of books. They provided the parallel.

Something is lost and I can see now that it may be me. The world, both human and planetary, seems to me to be broken and instead of fixing it we have simply removed our lives into some other, better, curated reality – inside screens, in the printed text, to a world we have made, like children, out of words and pictures. And I have fallen into the gap between the two.

If my condition is normal for my time of life, if it has a name and a little pill to match, then I don’t want to know it. I feel as though it’s the world that is sick – just that no one except me has noticed. Cassandritis, you could call it, and as I do so I can’t help hearing, with a shiver of rightness, the name hidden in that second syllable.

So I’m packing up and making a change. Nothing unusual about that; it is quite normal to take a sabbatical. I’ll just go for a year and come back wiser, or quieter, or more calm. I don’t expect, in midlife, to be offered any cloaks and I don’t think Virgil will stir himself for less than an epic poet, but I could put my faith in parallels. I’m not expecting things to be better anywhere else. I don’t know what I’m looking for. Hope perhaps.

Now that I have made the decision, now that I have resisted the pull to give in to the madness of it all, as if in reward, in these wide and graceful streets the sun is shining. London can be a lovely city when you are leaving it. Brisk light and shadow on the grand nineteenth-century buildings, and I am going to buy storage boxes, to put my life into.

The trees are in their autumn beauty and many people are out, holding hands, talking languages, walking. Nothing looks especially wrong. The homeless have been tidied, as far as possible, out of sight; swept into dust-heaps on every corner under the humps of their nonetheless stinking blankets. The newspapers, as on most days, cry outrage as though innocent, but everyone still has a hand to hold.

‘Don’t look at the down and outs. Don’t look at the hoardings,’ my one self says. ‘It may not be as bad as it looks and there are reasons for everything in life.’

Shops are reassuring places; I am immediately distracted.

I could buy a laundry basket that folds away, a peg box, a desk tidy in leaf print, an elephant-foot waste basket. The solutions are all here. Here you can look better, live better, improve your cars, kitchens, skin, hair, partner, clothes, desks, waste management, character. Everything is new. Nothing yet has failed or been spoilt. Nothing has betrayed its initial promise and there is everywhere so much well-lit space and so much choice. The swing doors open and shut continually, wafting the smell of factory-newness out into the street to tempt those outside to come in. Come in. Come in. And in and out again floods the obedient crowd, hurrying home to be better.

I start grazing, gathering up armfuls of new stuff before I’ve even reached the department where I will buy the storage boxes to put the old stuff in. This is exactly what I’ve always been looking for! And it is beautiful! And this! And look at this!

I come to my senses in the home-storage department, glazed with picking things up that I don’t need. ‘Put it down,’ my one self says to my other. ‘Put it all down. This too is madness.’ I reluctantly put away the desk tidy. I put away the elephant’s foot and the peg bag. Instead, I buy plain see-through plastic boxes with lids, for ten pounds a throw. I go home and put my clothes into them, folded carefully. They are pitifully visible through the sides of the box. I also put in my knick-knacks, pencils, notebooks, all my other belongings. I look at them too. The process is oddly ceremonial, like a burial, but ‘Nevertheless,’ I say to myself, ‘go on.’

The mansion flat where I live has an outside balcony with, at the back, a little room that used to be a privy, now a walk-in cupboard. The stuff that will fit will go in there. Someone else will have my room. The flat isn’t mine; it belongs to my aunt who is away in St Petersburg. So now I have no fixings, no place at all in this country of my birth, and this is a hard thing. I am sweeping myself from the surface of my life. Nevertheless, I go on. I carry the boxes out and stand them in a stack in the cupboard.

Down on the street, the woman with the carrier-bag three-piece suite, who thinks she is Britannia, hasn’t moved. I can see her out of the window each time I pass. She is still sitting among her belongings on her step. So I stop my packing, pull my phone from my pocket and look up ‘belongings’ and ‘belong’. The word has such emotional charge in English. I look up French, Spanish, Italian, German, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Greek. Only the Bulgarians have a word that has the same root for both. Most differentiate between possessions and people. They use two separate words. None of them use one that contains within it an equivalent of longing. Being and longing and belonging.

‘Belongings,’ my one self says, with authority, to my other. I like to pontificate. ‘Belongings don’t matter, whereas belonging does.’ But there’s no comfort here. My other self is hurled abruptly into mourning, among the drifts of possessions, and the see-through containers. Belongings do matter. They are little weights that tie us to our lives in time and place. These vases with frogs and flowers were given to me as a child. This pot with a cow on it my son made when he was seven. This picture I bought with my first earnings. These things are hooked and weighted like anchors, holding me moored to the fact of my life, my past. Who will I be when I’ve cast off?

When the van arrives and the rest of my furnishings, my pictures and all my books are driven off into storage I stand at the traffic lights, a lone figure, stationary among a flood of movement, while the people and the traffic pour relentlessly past, either side. I watch the van out of sight. And BritAnnia snug among her bags, on her doorstep, watches me. Now I have nothing. I feel lightly giddy, as though whatever force holds my feet to their print on the ground might slacken suddenly, as though I might unmoor and float away. My belongings were so solid, such tangible proof of my life in reality, of myself. Without them there is no evidence; nothing left but the finite mess of body that I am, and my waning life which floats constantly in front of me, lit like a moon.

Normally, under these conditions, there would be a guide to take me by the hand, to lead me somewhere enlightening, show me things, explain. Quest literature is full of gods made into pillars of salt, or cloud; of sorcerers or genies, or, as I said before, epic poets returned from the grave. No one has yet come forward.

I am sitting on a railway bench, thinking about this, on a day when the sky has pulled itself down as far as my feet, thick as a duvet. I am waiting for a delayed train. Around me and away down the tracks whitish shadows bulk dim into the distance, even the most solid things reduced to suggestion. Little red tail-lights of trains to elsewhere swallowed in fog. Stillness. Foundering. On the digital board the estimated time of my train recedes into the future as if things had started running backwards. I’m not surprised.

I should say ‘we’. We are sitting on a railway bench, because I’m not in fact alone. I don’t have a guide, as such, but I have the man I share my life with. We are doing this together, although of the two of us I am the only one in extremis, the only one looking for answers. He isn’t bothered by the intractability of the world. He is never in one place for long enough to feel implicated by its failure.

‘The thing is,’ I tell him, ‘I was hoping for a guide to point us in the right direction.’

‘What do you mean?’ he says quickly. ‘I am a guide.’ It’s true. He is. He has a small travel business. He takes people round archaeological sites. He’s an expert on the ancient world – Greece and Rome in particular. ‘Won’t I do?’ He sounds mildly aggrieved.

‘I know, of course,’ I say, before correcting myself. ‘I mean, perfect.’ Although it isn’t. I had promised myself the obliterating gravitas of Virgil. There is nothing heavy about Rupert, his four decades of knowledge so lightly worn. To cover my confusion and to apologize, I say, ‘I was hoping you could do something like Virgil does for Dante; slap me in the face with the nature of man, show me the heart of life.’

He leans forward, his beard beaded with mist. ‘How often would you like slapping – daily? Or just once a week?’ He has his eyebrows lightly raised, his head ironically tilted. He knows if he slaps me I will slap him back. I look at him as he sits beside me. He doesn’t have the nose to be Virgil. Sideways on, his nose and his forehead make one line and his eyes, all the time, have the look of somewhere else. Also he has a kind of detachedness. He looks a bit like Hermes. It wouldn’t be hard to imagine…

‘Can’t you just pretend?’ he says, as if he’d read my thoughts. ‘If I was a god in disguise, you wouldn’t be able to tell.’ Now it is my turn to look ironic. He isn’t a god but it’s true: if he was, I wouldn’t know. He pulls a filled baguette out of the pocket of his old leather coat and begins wolfing through it as though it needed killing first.

‘What did Hermes do?’ I ask.

‘Well, his official title is the Psychopomp,’ he says between mouthfuls. ‘He’s a guide, traditionally of animals as well as people. He deals in dreams and cattle and technology. He is a trickster and a thief, and he guides souls on their final journey to the Underworld.’ I think on what he’s said. Some of it is OK.

‘Either way I will have to put you into my account,’ I say to him, half apologetic. I know he doesn’t like to be pinned down. ‘I mean, it wouldn’t be honest to leave you out. I’m not the sort of person who would just set off on a major journey by myself.’

He looks at me in silence, his mouth very full. After a while he swallows. ‘You can’t put someone called Rupert into a book,’ he replies, and goes back to eating.

He is right, though not for the reason he would have given. When I write his name down he drains out of it, as if the loops of the letters were holes in a sieve. Empty.

What shall I do – call him something else? Nothing else works. Everything I try feels false. I ask him what he thinks. He is silent again. Then he puts up one hand in front of his very full mouth to act as a shield. He always talks with his mouth full.

‘If you put me in, it won’t really be me. It will be someone else.’ Little flecks of something like pickle spray from his lips.

‘No,’ I say, hesitating, ‘it won’t… True.’ It is an odd paradox that for the sake of truth I have to use his real name, but that the result will be someone invented.

That seems to be the end of the conversation.

We need a vehicle. We are on our way to test-drive a second-hand campervan in which to make our journey. The dealership is in a hinterland of scrub outside Pangbourne, gorse mostly, being picked round by ponies in a cat’s cradle of electric fencing. We rock our way, by taxi, a little hopeless, up a track in and out of potholes to a concrete yard. The driver says he is happy to wait; lots to look at here. He says it like it’s the greatest joke ever made. It’s true, it’s a sorry set-up. There is a litter of forgotten-looking vans too big for what we want and a Portakabin, tilted as if standing on one leg ashamed, and well it might be. Out of it, as we pull up, comes someone blazing with reddish hair, part boy, part fox, with several sets of keys jingling in his hand and a cocky little terrier trotting behind him. His clothes look as though he had slept in them not just last night but for the whole of last week. But he is impossibly, almost embarrassingly handsome. I have to make myself look away. Instinctively I try pulling myself together. How have I got so old, so invisible? I look brightly round at the collapsed vehicles. The one we are trying out is very small. Rupert and the fox boy sit in the front seats, their shoulders touching and their heads hunched forward, and I, sitting sideways on one of the benches, can’t see out of the back windows unless I fold myself in half. When the boy turns the key there is complete silence. The van is dead. Unfazed, he hops out and jump-leads it back to life.

‘It’s not the fastest,’ he says as we move at a slow running pace, back down the track. ‘But once it’s going, it’ll go forever.’ In the rear-view mirror I can’t help noticing that my mouth is open. I shut it and look at the needle of the speedometer. We are on the open road. It is trembling with effort, trying to hold itself at sixty.

‘Thanks,’ Rupert says over the rattle of the engine. ‘We’ll have a think.’ He says it in a way that means ‘we are not interested’ and ‘you’ll never hear from us again’ and I find myself surprised because, despite the jump-leads, despite the junkyard hopelessness of the outfit, I am not able to see past the fox boy’s patter, the power of his blazing looks. Obviously, or so I thought, we were going to buy it.

Finally, days later, we settle on a second-hand Romahome. It is fifteen feet by five, more or less, made of yachting fibreglass on the Isle of Wight, an upside-down boat on wheels. A good vessel for an upside-down time. I like the fact that its name is that of a tribe of outsiders, and I like the fact that, read backwards, it spells amor. Let’s hope that will be some protection.

London to Greece overland, to the island of Syros, is where we are going. You can fly the distance in a few hours and one change. It isn’t what people consider ‘a journey’. But we are going by parallel. We plan on taking months.

We provision ourselves for the trip. We buy a fold-up colander to save space, teabags for a continent devoted to coffee, a fold-up steamer so we can cook two things in one pot, a fold-up shovel for latrine digging, a camping shower that can be hung from a tree. Or rather, Rupert buys. The wood has closed about me again and I am in a different place. In this savage and extreme world, why are we busying ourselves buying kettles? I walk round the shops very carefully, newly aware that my body, which is all I have, is very soft, very puncturable.

Rupert considers torches, maps, e-guide books. He makes lists and crosses things off. Sometimes he asks me, sometimes he just looks at me as if to ask and then carries on. The closer the deadline comes, the worse it gets. I leave my purse in a shop in Richmond and he travels the two-hour round-trip to retrieve it for me as a matter of course. I am aware all the time that I am being very gently carried. I don’t feel bad. It is a matter of practicality. I haven’t actually checked but it feels now as though I have no skin at all, as though the complex networks of vein and muscle, the wet mesh of my capillaries, are directly exposed to London’s air. I worry briefly about grit.

Meanwhile, on the floor in the flat’s sitting room we make piles of books, among them The New Penguin Book of English Verse which is as heavy as an anchor chain and I hope will do the same job. This is the oddest thing – the side by side of normality and crisis. A flayed person carrying out mundanities. Rupert, who isn’t flayed, walks endlessly about the streets buying, organizing, clicking his fingers. He likes clicking. He clicks his fingers all the time; not the ones I would use – the first and second – but the fourth. He can do both hands. He’s very popular. I have known him since I was eighteen but it seems as if I am seeing these things for the first time. Did I notice before? I honestly can’t remember. Everywhere we go we bump into people who seem to know him. He greets them all ecstatically; someone he knew from New York, someone who worked in a restaurant he once owned.

‘Hey, Steve!’ he says in response to a shout of delight in the Portobello Road.

‘Steve? What Steve? Don’t you Steve me!’ says Steve, whose name is Tom. Rupert laughs but afterwards, ashamed, he says to me, ‘That was terrible, poor Tom. I just didn’t remember.’ I say nothing because I think I’m not there.

In the final week we make a farewell tour of various friends, parking in their driveways and serving them tea in the van. ‘Hilarious,’ they keep on saying. But I, as always, am serious.

On the evening of our departure my brother comes to the flat with celebratory food and drink. Both my selves are reduced to a kind of stunned silence but I eat and talk banalities nonetheless. Questing takes a certain type of courage, or so it seems, sloughing the familiar and accepting what will come. That’s why, in books, it is done by heroes, or by those who have nothing to lose. For a long time now I have doubted my resilience.

After supper we load the van into the small hours, cramming into the tiny lift, up and down from the third floor with armfuls of luggage. In the van my brother and I stow things into overhead cupboards until they are rammed. He is cheerful and tender. He hopes I will have an exciting time. I am to send him regular updates on where I am and what I see. He doesn’t say anything about whether or not my skin is still in place. But then, he isn’t looking for damage. Why would he? This looks like a normal thing I am doing; going away on an extended trip because my three children are now grown up.

Rupert is nonchalantly still packing. Weighed down with bags and rucksacks, my brother and I wait again by the lift. The pressure which has been building all day breaks in a bomb-blast of thunder. We stop and listen. Uninterrupted drown-fall. My brother and I look at each other. ‘Portent,’ he says.

Outside on the balcony, when we go to see, water-sheets are hanging in the dark. And in the flat the rain pours into my aunt’s bedroom through the ceiling. We run to and fro with trays and saucepans. We move the furniture aside. Everything is dissolving. There is the sound of drumming. ‘This is not apocalypse’, my one self tells my wide-eyed other. ‘It’s just a violent weather pattern.’

When the rain ends we pack a final load into the creaking van and go to bed. This is the last night, but I don’t sleep. I lie in my bed listening to Rupert’s untroubled breathing, and the night city. Nothing has drowned; the traffic, the people on the streets, all the great machinery of global society still turning. I lie on my back looking at the ceiling that I now know is permeable. I clench my hands under the covers. ‘What are you so afraid of?’ my one self says to my other. In my head, it is D.H. Lawrence who answers.

‘Sometimes,’ he says, his consonants clattering like little slips of shale on the hard hills of his native landscape. ‘Sometimes, snakes can’t slough. They can’t burst their old skin. Then they go sick and die inside the old skin, and nobody ever sees the new pattern. It needs a real desperate recklessness to burst your old skin at last. You simply don’t care what happens to you, if you rip yourself in two, so long as you do get out. It also needs a real belief in the new skin. Otherwise you are likely never to make the effort. Then you gradually sicken and go rotten and die in the old skin.’

Maybe I’m not flayed after all. Maybe I’m just rotting. I may be sick already. We all may be. ‘I’m frightened of change,’ my one self whispers to my other, ‘for myself and for everything else. I can’t tell where I stop and where the world starts and I don’t want either one to burst.’

My other self has no answer. Everything seems so shifting, so uncertain as if our civilization or even our whole species has found itself failing Lawrence’s test. The rising chatter of opinion, escapism in all our art forms, while violence of every kind runs riot in a dying world. Everywhere, the old, the comfortable bonds are loosening. The people I saw in the London streets, on the day I went out to buy boxes, holding hands, talking languages in the sun and the flying wind, are drifting unconsciously apart. Soon we will all be out of reach.

Departure. England has decided to look its best, washed luminous by the last night’s rain, but I harden my heart. I have fallen out of love with my country. In the London Underground recently they have been handing out badges encouraging conversation. Tube Chat, the badges say. A cosy attempt to lessen our cultural isolation, our horror at breaking the silence of strangers. But it is very difficult for an island not to be isolated – its nature is right there, rooted in its own name.

We drive slowly out of London, past places I’ve never been before. The lighthouse at Trinity Buoy, which has lost its purpose and is the size of a toy, and the towering City, which is taking its place. Where new towers have yet to rise, cranes rest against the sky. They look delicate, unaware of what they are creating; this mouth crammed with glass fangs.

‘All the better to eat you with, my dear,’ the City says to itself as we pass.

Rupert is driving. The radio is on and his telephone rings incessantly – each time he has to answer it with one hand and turn down the music with the other. He bobs up his knees to steady the steering wheel. He drives sometimes for quite a distance like this, using his knees to steer. I should care but it seems I don’t. I just let myself be carried, my two selves sunk like stones to an inaccessible bottom, as if it had happened and I were actually dead already, carried to the afterlife with my few necessaries around me. This is Hermes’ job, guiding souls down to the edge of the Underworld. Maybe Rupert is Hermes after all.

‘Yep,’ he is saying into his phone, ‘yep, I can do that… Send me the details and we can discuss it all when I’ve got them in front of me… No problem.’

‘A lot of people seem to need your services,’ I say when he finishes the latest call.

He nods. ‘I am much in demand.’

Even above the telephone and the music the van clatters constantly, the gas-cooker fittings, the crockery and glasses in the cupboards. As on a boat, you know you are travelling. I can’t help glancing into the back every now and then, until I get used to the noise, to check that everything is still safely stowed.

Outside, the countryside is caught in the current of autumn. Woods crowd to the horizon either side. Kent dressed to the skyline for departure, under a patchwork sky. And everything, it seems, is lit with leaving, my thoughts shedding and drifting as if they too were seasonal.

‘Are you OK, England?’ I ask it only now that I’m leaving, half surprised to find I mind. As if in answer, up ahead, smoke billows in the distance. On the hard shoulder a police car is in Hollywood flames. Everyone speeds by as if it was normal. Bizarre. I blink and swivel round to check I’m not dreaming. I am not. We continue.

Now, on our right, there is the sea, dotted with ferries going different ways, and a castle squatting dour on its hill with a matching town down below. We have got as far as Dover.

The town, when we enter it, seems forgotten, turning its back and facing landward as if the port didn’t matter, the few inhabitants who happen to be out wind-blown along its streets with lowered heads. Everything looks ill-assorted, as though no one had cared or thought it through. Once elegant houses in streets that have either lost track of where they were going or just given up in the face of a one-way system, cower in the shadow of giant ferries.

We buy porridge oats in the supermarket and food for supper, one lemon, some pasta and a head of broccoli. I had almost hoped we wouldn’t be able to go but the boat is not full. We can cross at 18.20.

Goodbye then, England. I have no idea what you are. Are you the books that I read, or the language I still love?

It is evening. There is no one on the quay. The windows of the houses appear blank as we pull away. I look at these famous chalk cliffs and the rising hills behind. I look at the single trees in outline on their ridges, and their woods of oak and ash. I think of the stubborn ground and its weeds and of all the bodies of water up and down the country; the ponds and the quick rivers, the ones clear to their pebbled beds, or the ones still with silt; and I think of the man-made fields and little hedges and I roll them all up together. Is that what you are, England – just the landscape I know in my bones?

Nothing answers of course, and it is late in the day to be asking, but that doesn’t stop me. It seems an urgent question. I lean out as if to make England hear. It seems I have to know before I leave.

Or are you maybe something else?

Something more shifting, like the tiny woman that I saw once passing, bolt upright and alone, in the back of an enormous car; or the long lines of her people, generations of them, stubbornly shelved in classes? Or tea, or pubs, or football? It is getting more difficult to see. I don’t know in the end what England is or ever was. I don’t know if it is much different from anywhere else.

We stand at the rail, watching. Everything is opalescent, palest grey. Pink and gold and pale blue. One or two birds wheeling. All at once, as we wait, little lights spring on everywhere at the same time and the darkness comes, like a seepage, not down but through; the world turning itself inside out like a trick. Or England removing itself quietly, leaving nothing behind. Gone. Just the lights sparkling on a black ground, a second night sky mirroring the coming stars.

Noise and juddering until Calais. From white cliffs to white fences. Miles of them, under harsh lighting, high and doubled, with coils of barbed wire at the top. The Jungle. Another bigger and worse forest to get lost in. ‘Think yourself lucky.’ It seems my one self has perspective, at least.

‘Give it a rest,’ my other self says, but still, as the fence unrolls its length, I look. There are up to ten thousand people here we are told, landless, in transition, in a rigged-up horror of tents and pallets. None of them are visible as we pass. In fact there seems to be nothing at all either side until further on black police vans solidify out of the dark, driving fast with lights flashing. I count six that scream by and a little knot of them later, stationary by the white fences. Police in riot gear with their backs to the road, looking in. I can’t see any opposition, only darkness.

We drive slowly through the outskirts of Calais, peering at street signs. France looks immediately different. Low buildings of a larger landmass. Wider apart. Quiet streets. Place Crèvecoeur. We are not going on the motorway. We are taking the coastal road, which winds among dunes with the lights of England constantly in view to our right.

We stop short of Boulogne, at a campsite. It seems strange and vaguely unwelcoming. In the van’s headlights as we look for our pitch, caravans and campers, their windows dark as if abandoned, stand about in little plots of exhausted grass. It is a curious no-place to arrive at and it isn’t home. We can plug into the power if we want. The showers and toilets are a walk away. It seems too far and too complicated. I settle wearily into the feeling of travel-grime. Maybe I won’t bother to wash until we get to Greece. I decide to read the campervan manual. ‘Continental power is often reversed so live and neutral change places. You should check first as it will override all safety devices.’ I have no idea how to check. I stare at the page. ‘It will no longer be possible to prevent electric shocks and may permanently damage equipment.’ There are thinly drawn diagrams of the electric circuits in the van. They don’t seem to translate to any of the switches in view. It is in English but still I feel I have entered a community whose language I do not speak. Both our phones are dead. This never happens in the modern world. We are cut off.

It rains all night. I listen to it drumming on the roof of the van. But my one self was right. Thank God it isn’t a tent. Thank God it isn’t a tent.

On the way to the showers in the morning I pass a pétanque court under water.

The campsite is next to the beach. Marram grass and a few pines and a grey sea whose waves jerk as if tied to each other, tugging and pulling in different directions. Horizontal rain still. The showers don’t work. I run to the campsite office to ask about hot water and am hurled through the door by a gust of wind, so that the rain arrives ahead of me at the reception desk.

‘Lovely weather I see, just like in England.’

‘That’s because we are neighbours.’

Two women with coiffed hair, despite the weather. They are sensibly wearing anoraks at the desk. Neither of them seems insulted by my nationality. Still, I can feel the components of apology rolling separately, as if they were ball-bearings, to the tip of my tongue. It is a new condition I’ve developed, a form of Tourettes, connected to the coldness of elective insularity. I look at the ladies behind the desk. Who am I apologizing to? They don’t obviously mind. I close my mouth to stop anything unnecessary rolling out. Their manners are pleasant as though they have been polite for centuries. Courtesy, from the Old French courteis, so they must have been. They don’t over-smile or tell me their names or ask if I have found everything to my liking. I think I have perhaps arrived in the land of the grown-ups. I take two little bronze jetons to put into the shower slot.

I thought the French were supposed to be rude. Rude also comes from Old French, although originally Latin. I can still see England across the water, a low, tussocky outline, stupidly close. Maybe if I didn’t know I was in France, I wouldn’t be looking for difference.

But it is different. You would have to be stupid not to notice.

The windows, when we drive into Boulogne later, are different; the height of the roofs; the dormers with space above the window as though their eyebrows were raised. The slim buildings that look taller than ours, the wide streets, the giant church, cavernous, smelling of stone and scented dust. The language. The supermarket, where there is no fresh milk. We look up and down the aisles. Just banks of UHT. We buy instead a chipped glass lid for the saucepan we already have. At the checkout Rupert points to the chip. Might there be a reduction? The girl passes the question on to her superior. Again no over-smile, in fact this time the reverse. Her superior says dismissively, and without looking at us, ‘It is bought as seen.’ Good, a rude French person.

As if someone had simply wiped the sky clean, the weather lifts. Windy and blue. Later, off a cobbled street so quaint it looks like something from a film set, we have fish soup and WiFi for lunch, served to us by a man whose face and voice are made out of ash. He has an elaborate and worn routine. ‘Oui Madame’, rolling his eyes and emphasizing the madame at every request. Through the window I can see him handing out dishes and repeating his patter. Gales of laughter blow through to the back where we sit in the half dark, sucking up soup and electricity. Something has lifted inside me. Maybe it’s crossing the Channel and leaving England. Maybe it’s the different buildings. Or maybe it’s just the sky – as if I too had been wiped clean, or is this my new skin? Whatever it is, I feel different.

‘So?’ I say to Rupert.

‘Yes?’ He doesn’t look up.

‘Well… How do you feel? I mean, nothing has really happened yet.’

Rupert is looking at his computer screen, his face lit with its underworld light. ‘How do I feel?’ He is busy doing I don’t know what. I can hear him clicking on links, travelling sideways in some other, internet dimension. ‘What exactly were you expecting?’ He speaks slowly because he’s only half concentrating and without taking his eyes off what he is doing. What is he doing?

‘I don’t know,’ I say. I look at my surroundings, at the fakeness of the real cobbles, this dark café, with its ashy owner. This, now I come to notice it, inedible viscous soup. ‘I don’t know. Something.’

‘What something?’ Rupert looks up. ‘We’ve only just started.’

‘I said I don’t know. I mean, what am I supposed to be looking for?’ My voice is barely above a whisper. The emptiness of the restaurant is making me self-conscious. Even so, it sounds urgent, impatient. ‘I just don’t want to miss anything.’

Rupert is engrossed again in his screen. ‘Mhmm.’ It isn’t much of an answer.

‘What are you looking at? Are you gaming?’

‘Gaming?’ He looks up again. ‘I’m researching campsites.’ But when I get up to go to the toilet I can’t help noticing he is watching pratfalls on YouTube.

It’s a bit disappointing. In the journeys I have in mind, the travellers throw themselves energetically upon chance and are met as they go by hungry old men asking to share their lunch, or by talking animals. They are tested at every turn or they are offered advice and, if they pass the test or heed the advice, they are given things that will help on the journey; a magic key, an amulet, an always-full porridge bowl. I push the soup away from me and Rupert looks up at last. ‘Alright,’ he says, snapping shut his computer. ‘Let’s go and look at the church and the museum.’

I jump up. The ashy waiter’s chauvinism extends as far as bill-paying so I hurry out, leaving Rupert to settle. I look up and down the street. Maybe a test will present itself. But Boulogne is disappointingly empty. There are no people and I see no animals, let alone ones gifted with speech. We are approached only once on our way, diagonally across the street, by a heavy-looking man with a soft, ingratiating voice. He is already talking by the time he comes level. His tongue is large and very pink and he speaks to us in ornate English.

‘Excuse me, sir and madam, could you give me some money? I need to eat.’ He has been eating a great deal, that much is obvious, but he is asking strangers for money and I am not, or not yet. Besides, I know this test. You must share what you have with an open heart or you won’t make it to the next level. We give him money, only one of us with a vested interest. The stories don’t say if it is enough for one person to have an open heart.