Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

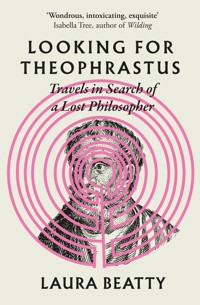

Who is Theophrastus, and why should we care? Once, he was the equal of Plato and Aristotle. Together he and Aristotle invented science. Alone he invented Botany. The character of the Wife of Bath is his invention, the Canterbury Tales as a whole, perhaps, the product of his inspiration. When Linnaeus was developing our modern system of plant taxonomy, it was Theophrastus' work on plants that he used as a basis. So how could one man do so much and still sink almost without a trace? This is the story of a journey to find him and bring him back from oblivion. Looking for Theophrastus, in all the places he must have walked and lived, it tells how he and Aristotle, his friend and tutor, broke with the philosophical conventions of the Academy and left on their own adventure; of how together they invented what we now take for granted as the Natural Sciences; how, not content with that, they made the great experiment of applying philosophy directly to the practicalities of government through the tutoring of Alexander the Great; how they were disappointed and how, in the end, they returned to Athens and founded the famous Lyceum. Against the dramatic context of his time - the end of democracy in Athens and the rise of Alexander the Great; the great battles and vast territorial expansion that followed; the flowering of the philosophy schools on which so much of our culture and thinking is founded - and on, following his cultural legacy through to the modern day, it explores how we perceive, understand and, most importantly, how we relate to the world around us, questioning what we lose from our way of living when we forget those ancients who first taught us how to see.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 463

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Laura Beatty

Lost PropertyDarklingLillie LangtryPollard

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Laura Beatty, 2022

The moral right of Laura Beatty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

With thanks to Cambridge University Press for permission to quote from Theophrastus: Characters, translation by James Diggle.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 438 3EBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 437 6

Design www.benstudios.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Rupert

And might it not be… that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time, so to speak?

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz

I

The Man

If it happened, then someone must have seen it. A fisherman coming home across an evening sea, one early star burning on the horizon and the sky still light. There, ahead of him, something bobbing on the water – the head, a little pale balloon with its ribbon of blood unwinding behind it all the way to the horizon.

Or maybe it wasn’t like that. Maybe the fisherman heard it before he saw it; first thinking it a seagull’s cry, but then thinking, no – it isn’t that, someone is singing. So he looked around to see where it came from, this strong, unearthly song. Could it be coming from there, that little collection of flotsam? It is likely that there was other detritus from the murder. The flesh and bones, the coils of things normally hidden and now spilled out, floating on the sea’s surface, rising and falling with the swell. There, in the middle of it all, would have been the head, singing. Because that is the important point – not the murder, not the women tearing him apart with maddened hands, but the fact that the song refused to die. It went on unchanged, pouring out of the dismembered man’s mouth as if nothing had happened, on and on, all the way down the Hebros river and out across the sea, until the head landed, still singing, on a beach on the island of Lesbos. That was the greatest outrage, that one human being’s song could do that, cheat time – that Orpheus’ music was so free it was death-proof.

*

It is evening, October and windy; I’m standing at the rail of a ship, a ferry, waiting to leave Piraeus for Lesbos, where the head of Orpheus came to rest. Below me, on the empty quayside, one or two cars are parked, men are set up for fishing over propped rods. The dark is fast coming down. Somewhere there is music playing – Greek music, with its strange running and halting rhythms. I lean and listen to the tune, now fast, now slow, now fast again, on its endless, trance-inducing round.

At the dock’s abrupt edge, a family, with a set of white plastic tables and chairs, dines quietly, as if they were in their own home. The music is coming from the open window of their parked car, as they pass each other salads in little Tupperware dishes. Above them, the ferry – which is in proportion to the sea not the land – bulks gigantic against the dock. It is not human in scale, so what on earth kind of journey are you taking, I find myself thinking, if this is your vehicle of choice?

I’m going a long way – much further than the 143 or so nautical miles between Athens and Lesbos. I’m going back about 2,400 years to find someone, a philosopher whose work once burned itself across the sky of Western thought, and then somehow fell into darkness and was gone.

A forgotten philosopher? Why on earth would we need one of those, let alone one from so impenetrably far back in human history? Well, because this one is different: less titanic perhaps but more modern in his thinking, more recognizable and therefore more relevant to now. For a start, he comes not from the grandeur and confidence of classical Greece, but from the moment of muddle and compromise just after it, when Athens’ grip on its own world was slipping and the dream of democracy was dying.

I was familiar enough with classical Greece, with its myths and its poetry, its confident statues and its architecturally astonishing temples. I knew it first, as a child, in its mythic mode, as a place of slippage – a Narnia for grown-ups, whose woods were full of centaurs and whose people turned into trees, or stones. Then, later, I knew it in its heroic and tragic mode, as a place of grandeur and clanging bronze, governed by fate and made of gold, very, very far back in time and unassailable in its almost perfection. What it never was, or what I could never see, was its ordinary mode, its day to day.

Then, about ten years ago, I came across something else, something very unexpected. It was a little green book of character sketches and the sketches were of ordinary people – people like the Chatterbox, who sits next to a stranger he’s never met before and first launches into singing his own wife’s praises, then recounts the dream he had last night, then describes in every detail what he had for dinner. Then, as no one has managed to stop him, he carries right on saying things like, ‘People nowadays are far less well-behaved than in the olden days… The city is crammed with foreigners. A little more rain would be good for the crops.’

These people were out and about in the marketplace, in and out of each other’s houses for dinner. They were gossips and flatterers, and farmers, and city boys, all talking in their own ordinary voices, in their ordinary clothes, among the clutter of their ordinary possessions.

How could something so long ago feel so immediately present? It was as if all the previously invisible, unmentioned and unimaginable humdrum of unassailable Athens had catapulted itself suddenly into my writing room. I didn’t know what to make of it. Where, in the canon, did it fit? It was so different. It read like something out of a novel but it was two thousand years too early. I looked again at the name on the cover: Theophrastus. It wasn’t like anything else I’d ever read. I sat holding the book in my hands and wondering about its author.

How do you know how to do this, Theophrastus? What is this? I’ve been reading for years and I’ve never even heard of you. Who exactly are you?

Very little has survived to answer my questions but I started to see what I could find. I picked through the fragments and soon, like catching sight of someone out of the corner of your eye, always just as they disappear, I began to glimpse a man who seemed always intent, who looked at everything with focused attention, no matter how big or small. Someone who asked, in between his researches into metaphysics, philosophy, law and logic, what are these tiny creatures? What are these flowers at my feet, up again out of the dead ground? What are these stones, these storms, these winds that walk in on us out of the horizon with such devastating authority? He was one of the first to hold conversation with the world and, with no instruments to help him other than his own mind, to try to write down how it works, how it started.

‘Theophrastus who?’ people say, when I mention him. ‘Never heard of him,’ and ‘Bless you!’ one person says, thinking his name is the sound of a sneeze.

So I’m going to fetch him and bring him back. I’m going to the place where he’s still dimly present, living out a shadow-life in the monochrome underworld of written memory – hence Orpheus. The point about Orpheus is that he doesn’t just look nostalgically back to a better time – he goes and fetches the past, with his music, and brings it forwards; and that, to me, has always seemed a more useful direction. I will need a song, perhaps, like the one playing below me, or something else from Orpheus’ armoury. Either way, I’m going to look for Theophrastus in all the places where he lived and then lead him forwards into the present, so that his life can run again across our own time, if only for a moment.

Below me, on the dock, the family’s quickening music mixes with the sound of the sea – the changing rhythms of a Greek dance, which, in its circularity, is another thing that is unending. And that would be another way to enter the Underworld: dancing. That would be a good way to bring someone back from the dead. I’ve seen the Greeks on ancient pots, even before Theophrastus’ time, dancing just the same as they do now, with their arms round each other’s shoulders, circling and circling as if, between then and now, the running, halting rhythms continually unwind and check and change but never stop. That’s all I need, something to hold time up for long enough to get there, and then to get back, something to change time’s insistent linearity, its always forward motion, something to hold it in place.

Out beyond the harbour, the sea has turned heaving and poisonous, although the crew don’t seem to have noticed. Have they not seen? Because already the gangplank is lifting. Up and down its rising incline the men in boilersuits run reckless, while the walkie-talkies in their pockets crackle like fireworks. I look at the land behind; the little lights coming on in the houses. I’ve changed my mind. I want to get off. But the ropes are flung back to the loosened ship and already the anchor chain runs rattling home. It is too late. I am committed. Above me the foghorn sounds twice and, in a foulness of fuel and churning water, the ferry eases back, and abandons itself to the sea and the coming dark.

Behind us as we slide away, the few people on the shore stand motionless and only half watching. With unfocused eyes, they witness the ferry dwindle until it’s just a chock rolling in a waste of waters.

An hour or so later, it is fully dark when I look through the porthole. Black mountains of water heap and slide. Anything could be happening out there. Somewhere on the same waterway – but in a smaller vessel, one that bucks in the waves like a pony – Theophrastus crosses and re-crosses, still passing swiftly by, now on the landward side, now on the seaward. Or he chases behind us, on one of his journeys, making for Athens, or Lesbos, or Anatolia – perhaps the first time he made the journey to Athens, impatient, on his way to Plato’s Academy, leaning his body into the wind in excitement, while the ropes sing and the water slaps over the side. He is watching with screwed-up eyes for the first sign: the sight of Athene’s bronze crest, her spear-tip flashing in the light, a thirty-foot metal woman brooding over the city that took her name. Look for it as soon as you pass the temple at Cape Sounion. That’s what he’s been told. That is where it’s first visible. And then the Athenians on the trading ship pointing her out with shouts, recognizing home.

I too look out for Cape Sounion, illuminated now by electric light, its frail skeleton put down on the hilltop like something forgotten. Odd and ancient and without use any more, while the Aegean slides by in the dark, and all night the ferry rolls, blunt and dogged, persisting through heavy seas. Intermittently, because I can’t sleep, I peer through the porthole at the mountains made of water. I think of Theophrastus braving the sea back and forth in his smaller, engineless boat. You are far less fearful than me. The ship descends and rises, occasionally hitting a wave face-on with a juddering smack. Tens of feet up from the waterline, I watch the spray shoot up against the glass. I will pray to anyone who will prevent my shipwreck. And I mean anyone.

*

In the morning, I come up on deck like someone stunned, to find a different world, the ferry easing through blue seas, under an open sky. We’re coming into port. Here is Mytilene, Lesbos’ capital city, with the sweet curve of its harbour, its dome and its gracious looks, doubling itself in glassy waters. I totter down the gangplank and along the waterfront as far as a coffee house. I’ve arrived.

The coffee house has a high ceiling, and turn-of-the-century grandeur. Huge arched windows look out at the harbour. It is so light, and it is so big that it runs the length of the block, its far end opening onto the shopping street behind. You can order a latte here, which comes in a cup like a bowl, accompanied by two mysterious, powdery, half-sweet biscuits; you can balance out your tiredness with caffeine and you can adjust. There is plenty to look at. Everyone, it seems, is passing through. Everyone is talking. They look like people from Theophrastus’ Characters. Old ladies whose bodies have melted downwards into bulging ankles. Young men with slicked-back looks who whistle through their teeth and hurry by. Men with stomachs like footballs and light-coloured shoes; and men shuffling by in vests and braces, their hands holding plastic bags stuffed with what seem to be dock-leaves. I nest myself in this hubbub. I listen to the gulls crying, the foreign conversations, the foreign traffic noise – different horns, different sirens, scooters. I put my hands around the cup and look at the pale coffee and think of the distances I’ve travelled – of the long miles and the long, long time that there have been things to look at and people present to do the looking. And I’m looking, myself, for the man who started it all, who taught us first how to do it, how to use our eyes.

Only he isn’t here. I’m imagining him in the boat that crossed my path in the night. I’m imagining him, arriving at his own destination, in his own morning, approaching Piraeus, which I have long left. Slower because he is under sail – and in the shadow of triremes, the famous Greek fighter ships with their three banks of oars, turning and manoeuvring, out on exercise in the water beyond the harbour. Close to, on the seaward side as the little vessel nears land, a trireme, perhaps in the process of swinging round, holds itself steady for a moment, as if catching its breath. Then comes the roar, O opop, O opop, as the rowing chant breaks out again and 170 oarsmen bend and pull and the ship leaps forward like a fighting dog.

On the little merchant vessel, they stand at the gunwale, turning their heads in admiration as it shoots past. The speed of it! The oars hissing in the water like heated knives and the metalled prow flashing. The noise and the force of it, as it slices through the water with its painted eye staring, and on the deck of the merchant vessel the watchers suck in their breath and shiver because this is the power of Athens.

Then into the harbour itself, in a glitter of water, between boats that jostle and bob at several commercial jetties. On the quay, where a family is perhaps picnicking, cargoes are unloaded and it is noisy – shouts, whistles, gulls crying. Crates and sacks stacked. Grain from the Black Sea and the Nile delta, Egyptian slaves, the cloth that Theophrastus’ father finishes, terracotta, and garum (a condiment made from fish guts that is Lesbos’ most prized export). In the naval harbour, the warships coming in are hauled up the slipways into the ship-sheds to another shouted chant, and the oarsmen stand, massive, and walk to and fro, among piles of ship’s tackle. Here and there, the city’s notables, the men who finance the triremes, hold conversation with their captains, rings flashing on their hands as they point and talk.

And Theophrastus would have come down the gangplank into all this hubbub for the first time, aged about seventeen, as disoriented as I am in Mytilene. His possessions thrown down to the quay and the noise rising up around him and the strange feeling of standing on solid ground after so long on the rocking deck of a ship. It is roughly 355 bce. He has come to Athens so he can study under Plato. Is he met by someone? Does he have a contact or a friend of his father’s to guide him, or does he just shoulder his bundles and set out alone, in the shadow of Themistocles’ walls, to travel the four and a half miles or so from Piraeus to Athens? Either way, his shoulders and the back of his head are visible only for a short while before he is lost among the steady traffic between the two towns, dust permanently raised in the wake of wagons. And when he arrives finally and passes through the Piraean Gate and into the muddle of streets beyond, if he hesitates at any point, if he stops to ask directions, he speaks in dialect, with a giveaway accent. He too is a foreigner.

For me, in my café, there are the soft, dropping sounds of Modern Greek, because Greek is a language made of ‘l’s and ‘k’s and softened ‘d’s, whispered and stopped at the front of the palate, like water running away over leaves and stones. ‘Poli kala’, the people say to each other repeatedly. ‘Oreia’. And they gather their bags and rise from their tables, or put their bags down and stop and talk, or start off again, doing whatever it is that people do in Greece, and which, whatever it is, looks better, or more mysterious, or more significant than anything I might have been doing, at this sort of time, ordinarily, in England.

And then, after a while, I leave. I go out into streets bright with striped light to find somewhere to stay, discovering by accident, up a side-street, the Hotel Alkaios, named after an ancient poet, with a courtyard full of trees covered in ripe pomegranates and red-shuttered windows to match. In a solidly furnished room, I flop onto a bed at last and stare at the ceiling, and ask myself how on earth you go about finding a man who has been dead for over two thousand years.

Orpheus, who is now known only for taking his wife back from the dead, may actually have existed, in some far distant past, as a Thracian philosopher and musician, but whether he did or whether he didn’t, a myth grew up about him. In Homer, ‘mythos’ simply means ‘word’, or ‘speech’ or ‘spoken account’, without distinguishing between truth or falsehood. Our modern meaning, which is a response to the idea of myth as story, is unhelpful in that it only represents untruth. It has forgotten its original purpose, which was to explain. In the beginning, myths were an attempt to answer our first question: why? They were the product of a powerful crossover between metaphysical thought and close observation: narratives that grew out of an attempt to understand an essential truth. They tried to explain why the world works as it does.

The myth that grew up around Orpheus is, among other things, an explanation of the nature of music. It is interested in how music relates to death and, in particular, how it relates to death’s servant, time. As we know, it tells how a musician, who had lost his wife, was allowed – alive – down to the Underworld to take her back, on the single condition that, as she followed him up, he did not once stop or look behind him, and how, just as he reached the lip of the world, he failed. He turned round and Eurydice dispersed before his eyes as if made of mist. It tells how Orpheus mourned Eurydice for the rest of his life and how finally he was torn apart by cultic women, some say for his rejection of their advances and some say just because the burden of his sorrowing was too great.

In other words, music creates its own conditions. It catches time into its own measure and makes it keep a different beat, and it catches up emotion and memory and holds them safe without our knowing. In music, we travel back to places or people that existed before – to a memory, or to a whole set of feelings – of first love, say, or first loss – under which conditions an eighty year old might find themselves dropped sheer over the cliff of being twenty again, or a man might find his dead wife alive. So long as Orpheus keeps moving forwards through his song, so long as he doesn’t either break or stop, Eurydice will be there.

I first read this myth as a child. I remember I read it several times, somehow hoping each time that between readings the ending might have changed – that Orpheus might, this time, have come to his senses and followed the simple instruction. Why was he so stupid? Why didn’t he do as I would have done – because I, as a child, had answers. I would have reached behind me, without looking, to hold her hand, to know that she was safe. I read it again. Why did Orpheus always look back?

I know now, of course. He looked back because he was grown-up. It is only as children that we live in a seemingly endless present, a place of waiting, in which we lean into the future, impatient, through the decades of snail-paced birthdays. We measure how much our feet have grown, how far we can spit, how tall we are, in a world where bigger is better. And then one day, who knows why, we turn round and look back.

*

Lying on my hotel bed, thinking about the Orpheus myth, about what the truth at its centre might be, I make my own journey backwards, to the self I lost at the edge of childhood, to the place where it all started. I remember the moment, in my own life, when I first turned round and saw my childhood self, pale as a ghost on the lip of the world, and thought it irretrievably lost. I was eleven and we’d just moved house. Under the wide, freewheeling skies and through the sugar-beet fields and among the woods and streams of Nottinghamshire, I’d had a wild, wide-ranging childhood. Then we moved to Reading, where I woke up, on the threshold of adolescence, boxed into a terraced house on the side of a busy road.

The town was hard, and the town was grey. Its pavements were grey and its buildings were grey and the birds that blew about its streets like litter – the gulls and the pigeons – were grey, as was my new school uniform. Reading closed itself around me with its always-indoors places. Even the sky was small and hemmed in, and at night it had to be lit up, as if it too was indoors; the soft silver of its own scattered lights swallowed in sodium glow.

We weren’t allowed to roam around. It was dangerous. It wasn’t clear how. At night, outside my bedroom, there was a drunk – was it just once, or every night? – staggering and groaning in the street below my window. Perhaps he was the danger. I didn’t know. In the mornings, I bicycled down the hill, past the sterile cherry blossom – not grey but so pink it might have been plastic – on my boy’s bike, on my way to my girls’ school.

I missed the stream, where we used to play. I missed the skies and the whirling winds. I missed the fields where the owl passed, white-faced, before bedtime, and his hollow hoot in the dark. I missed the world that had seemed to match my restlessness with its own, always changing, always turning through the circle of its seasons. But looking back now, I can see that what the move really marked was the end of childhood, the end of a particular way of being. It closed me into my body, and my body had become a place I did not want to be. I didn’t want this unstoppable plumping. I didn’t want this clock inside me, telling me monthly that I was now a woman. I wanted my old unbounded self. Where was the girlboy, fishbird, fluid thing I’d been before? How would I ever get used to this lesser, more restricted me? Where could I go, now I couldn’t leave my own body? Where could I roam, wide and wild, like I always had before?

*

I was twelve when I discovered ancient Greece. It was brightly lit, the Greece I first encountered, running with water, flickering with spirits and fluttering with draperies, a place where everything was fluid and shape-shifting. Its people were often only half-human, or human only half the time. They were half-god, half-goat or half-horse. In this respect, it restored the world I’d known in childhood, a wild and flowing world where everything was alive, where mind and body were yet undivided, the mind soaking up the world through the body, as if the two were unbounded and equal, the one shot through with the other, like a piece of cloth.

Instinctively, perhaps, when this was lost to me, I followed Orpheus back into myth, to where girls can become reeds or streams or deer, and where no boundary of time or species is so fixed it can’t be crossed. It was perhaps an odd choice for a child in Reading but I just liked what I’d glimpsed of the freedom and strangeness of the ancient world. It was a place I often went to with my questions, so it was no surprise that an answer should come from another story about Greece: Leonard Cottrell’s The Bull of Minos. I can’t now remember why I picked it up. It was a paperback, in an edition called Pan Piper Illustrated. There was something exotic-sounding about that. It had black and gold lettering on its red and white cover, the whole of the rest of which was filled with a black bull’s head: strange and savage-looking. It had a gold rosette on its forehead and long and finely tapering golden horns between which the title was caught. Something about it matched how I felt. I’d never seen anything like it before but I recognized it immediately, like something I had lost.

It is the account of three archaeological excavations, at Mycenae, the Minoan palace at Knossos, and ancient Troy. That makes it sound dry. It isn’t dry. It’s full of light and full of gold and both of those were the opposite of grey. More than that though, it is the story of the passionate exploration of a ruined civilization by two men who believed that the great myths they’d been told as children were historically true. I too knew the stories of Troy and its wooden horse, of Agamemnon and his terrible murder, and of King Minos and his labyrinth. I’d read them as stories, not as histories. If I had an instinctive feeling that myths existed to explain the nature of life, that didn’t mean I took them to be factual accounts. It had never occurred to me that there might be real places where, at some distant time, these things (or versions of them) had truly happened. So I followed Cottrell, as he followed his chosen archaeologists; he was often tired and disoriented by travel, often disappointed, often alone, as here, on a train at nightfall:

Glancing up when the train had been halted for nearly a minute I happened to see a station name-board in the yellow light of an oil lamp. It was Mycenae. Even as I snatched my bag from the rack and scrambled out of the carriage the absurdity of the situation struck me. To see the name of Agamemnon’s proud citadel, Homer’s ‘Mycenae, rich in gold’, the scene of Aeschylus’s epic tragedy, stuck on a station platform, was too bizarre. And yet there it was. And there was I, the sole occupant of the platform, watching the red rear-light of the little train as it slowly receded into the night.

For some reason, this was the paragraph that caught me – the idea that stories could be true, that a book could open like a door onto a real place, existing both now in the present, and also as it was in some other distant time. I loved the blurring of the edges of history, fiction and reality. I loved the slippage of travelling in three dimensions at once, through time, across geographical space and into story. And there was so much detail. There was this whole country where I’d never been – the drama of the digging, and the waiting and working, and the impossible dream of gold. There was the first breath-stopping glint of it, those long-lost possessions of kings lying, battered but intact, in the mud. But there was also the ordinariness of stations and grubby carriages and train lights. I was caught among the moonlit olive trees as Cottrell set out to walk to his lodgings, with his suitcase in his hand and the ancient stories in his head.

Behind him, my little box room in Reading forgotten, I too was setting out on that midnight road, free and fierce with intent, and with the glamour of the Greek myths moving like great shadowing clouds, somewhere in the air above me.

Over a lifetime, I’ve gone on reading these stories and histories and poems. They have represented to me something true but long lost, a way of relating to the world through the body as well as the mind, more than animal, a kind of mineral belonging, a communion in the fullest sense. More than that, in the case of Orpheus, they give me hope that if one can find a way around the instructions, some parallel means, then it might still be possible to get back what is lost.

*

So Orpheus’ story tells us how impossible we find it, not to look back with longing for what is gone; but while it shows us the trap we are caught in, it also gives us the key. It shows us the conditions under which the lost thing can be raised and re-lived, even if only for a while. In song, in music and in story, we are sidestepping time. That is what reading is. You can slip into a book like you slip into water and whatever you find there – just like whatever you find underwater – is a different but unquestionable reality. It lasts as long as it takes to read and you live it alongside your own life. What’s more, if it’s powerful enough, something of its atmosphere will remain, like silt from a risen river, to change the contours of your inner world, to colour your mind.

Theophrastus wasn’t his real name. He was born Tyrtamos, the son of a rich man, at Eresos on the western end of the south coast of Lesbos, in 372 BCE, or thereabouts.

Picture the island in the fourth century BCE, wide and fertile and well watered, folded protectively around two sea gulfs which loop up to its centre, full of fish and cuttlefish, and with birds circling overhead. It has been inhabited for several millennia already. It grows vines and olives, oak trees, walnuts, planes with their mosaic shade. It has boiling springs that fizz up out of volcanic rock to meet the sea in a hiss of steam. It has rivers and reedy flats and sudden streams and soft valleys and rugged, volcanic mountains. It has flowers in variety and profusion, a fallen forest of petrified trees. It is both one of the largest and one of the most topographically varied of the Greek islands.

All this is divided between five competing cities – Mytilene, Methymna, Antissa, Eresos and Pyrrha – each of which has its own distinct identity and each of which is reluctant to cede control to any other. The cities trade independently with the rest of the Greek world and as far afield as Egypt, often founding colonies along the way, at Assos on the coast of Anatolia for instance, or at the mouth of the Hebros river where Orpheus was dismembered, or on the Hellespont. Mytilene, which in Theophrastus’ time has sprawled to roughly the same size as Athens, has two harbours, one military and one mercantile, and is part of a powerful twelve-city trading cooperative that has a permanent emporium at Naucratis, on the Nile. The island exports many things: wine and alum and oil, textiles, terracotta and garum. Lesbos is rich.

It also prides itself on its cultural standing. Theophrastus would have grown up knowing that he came from the island where Orpheus’ severed head washed up, still singing, on the beach at Antissa. Both Achilles and Odysseus are supposed to have landed here. So, an island fixed in myth, blessed with poetry and music. By Theophrastus’ time it had already produced four of the great founding lyric poets of Greek tradition: Arion, Sappho, Alkaios and Terpander.

Theophrastus’ father was a fuller. He had a business cleaning woollen cloth, both in the process of making the fabric and afterwards, when it had become whatever it became – cloaks, blankets, tunics. Once, when asked who his friends were, Theophrastus answered quickly, How would I know? I am rich. Everyone had clothes that needed cleaning, after all. This was done by treading or pounding the cloth in a bath which contained a whitening agent, so for this reason Theophrastus’ father may also have traded in gypsum, which was the substance most commonly used. This was mined further south, on the islands of Samos and Melos. In an otherwise dry and impenetrable treatise on stones, Theophrastus wrote a description of the mines on Samos that is so precise, so detailed and so vivid that it has to be first hand. He must have seen the mines himself, I’m sure of it. And this is how one might follow him, sifting through what’s left of his writing, picking up the little details, like clues, as if tracking an animal by its spoor:

It is not possible to stand upright while digging in the pits of Samos, but a man has to lie on his back or his side. The vein stretches for a long way and is about two feet in height, though much greater in depth. It is surrounded on both sides by stone and is taken out of the space between… The earth is used mainly or solely for clothes.

So here Theophrastus is, so interested, so observant, that he notes the height of the seam, its length and depth. He compares it to gypsum from Melos, where it seems he has also been. Samian gypsum is beautiful… greasy, dense and smooth. How old is he? Still a boy, having made the trip down the coast of Asia Minor with his father, being shown the world of trade for the first time. And when they arrive at the quarry, watching in fierce sunlight and gypsum-dust while the men, caked white like ghosts, work the seam on their backs, it must have been hoped he would follow in the family business.

But he didn’t. Something else happened. Somewhere in spaces I can’t imagine: In a room? In an open space? In cool colonnades, or a garden, in a grove of trees, or under the shade of a single, spreading plane? I don’t know, but somewhere, Theophrastus was educated. Democracy demanded a literate population and Lesbos, at least while Theophrastus was growing up, was democratic. In Athens, all schedules of taxes, all legal cases and all new legislation had to be written up on white tablets and publicly exhibited, for everyone to read. So it follows that enough people were able to do so. In fact, it seems, from inscriptions found in the surrounding countryside, that even the shepherds may have been educated to some degree. Alphabets have been found carved into the rocks, in jumbled order, as though by someone practising – αβλ, where it should read αβγ, for instance – and in one place, the inscription, ‘I am bored watching sheep.’

Theophrastus’ teacher was called Alcippus, and from Alcippus he learned mathematics; he learned how to read, and how to write, holding a stylus and scratching his letters into a wax-covered tablet or writing passages out in ink. In one speech by the great orator Demosthenes, which attacks an opponent’s back-street upbringing, there is a snatched insight into the atmosphere of Ancient Greek schooling which makes it sound oddly Victorian:

But do you—you who are so proud and so contemptuous of others—compare your fortune with mine. In your childhood you were reared in abject poverty. You helped your father in the drudgery of a grammar-school, grinding the ink, sponging the benches, and sweeping the school-room, holding the position of a menial, not of a free-born boy.

From Alcippus, Theophrastus also learned poetry and systems of government. He learned the rhythm of reading a scroll using sticks to hold and unroll it to the length of a page at a time. One stick for the top of the roll and one for the bottom. At the end of the page length, he learned to allow the top of the scroll to roll down, trapping both sticks at the bottom as place marks. Then he’d push the whole scroll up the desk and roll down a page length again. Up, down, slide, up, down, slide, working the sticks in a kind of reading dance. Most of all, because scrolls were rare and precious, he learned to absorb information by ear, keep it, memorize it, organize it, frame and formulate his thoughts about it, and then to speak those thoughts out loud. Information was most quickly and widely transferred in speech, as if the transition from an oral to a literate society wasn’t something that simply switched from one to the other with the invention of writing but took place very slowly over a long period. In many ways, in Theophrastus’ time, Greece was still an oral culture. The ability to speak off the cuff, in public, was an essential skill.

So he learned how to speak formally, in passages, as we would now write, measuring his audience as he went. He learned how to catch attention – with words and with gesture. And how to use his voice itself – its range, its rise and fall – and then how to fit, in the flash of an instant, his thoughts into sounding words. He found that, together, speech and thought could combine, like a weight of water, could lift an audience and sweep it away. Why would you want to clean cloaks, or count money, or watch dust-caked slaves at a rock-face if you could do that?

*

He didn’t. He thought about it, what he might do. A soft and susceptible boy, the kind of boy who might have told himself secretly: what great thing I might one day be. A boy who laid out his collections of things, the carefully noticed same types of shell, the little lumps of minerals, and all the types of gypsum his father brought him. A boy who, when he undressed at night, quietly folded his clothes.

So, when the time came, he chose his moment and he faced his father and told him something of the dreams that were beating in his chest. How he wanted to learn, and to learn philosophy. How in Athens they were solving the nature of the world. They were going to be able to understand what it was, how it worked. They were going to think it out. How he must be there because, maybe, if he studied, he could make a difference. His mind was good and he felt so strongly the mystery of all these things. It must be possible, surely, with time and application, to understand how they work, what their principle of organization or purpose might be. He might just be the man to do it. Alcippus believed in him. If he could have this one chance, he might be another Plato.

Presumably Alcippus, who had studied at the Academy himself, put the idea into his head. The fulling business, so hopefully built up for Theophrastus’ future, was put to use funding his studies instead and off he went to the Academy at Athens, to study under Plato.

Plato was in his early seventies, working on the Timaeus, his attempt to describe the nature of the physical world. How can we know what we know, he was still asking, as he had been for years. How can we possibly trust our senses when they are so deeply subjective? But by now his thinking had become mathematical – numbers contained the only certainties he could trust.

Maybe Theophrastus had already heard of Plato’s image of perception, or maybe he heard it for the first time in Athens, listening in his new surroundings, electric with attention. How, according to Plato, we are in a place of darkness, sitting chained in a cave, with our backs to a high wall which partially blocks the cave’s only entrance. Along the top of the wall, people and animals are walking in front of a bright fire. It is their shadows that we watch, wavering and flickering in front of us, across the walls of the cave. That, Plato says, is what we think is real. If we could break the chains and walk up and out, and if we could recover from the blinding light of reality that would hit us as we emerged, we would see the things themselves, not just their shadows. They would be essential and absolute, not changing, not variable, not endlessly and puzzlingly different in small and pointless ways – we’d be able to see the blueprint (to use a modern term) that determines the water-ness of water, the tree-ness of a tree, or the cup-ness of a cup. These things are Plato’s ideal forms and they have the pure, irrefutable truth of mathematics. They are. And we will only reach them, Plato taught, through abstract calculation and through thought.

Imagine Theophrastus listening and thinking. Trying Plato’s ideas out for himself. Information pours into him all the time, through all his senses. There are five in total – as if for the purpose of corroboration – are we really to mistrust them all? Beside him some Athenian stranger shifts. He can see the youth’s tunic. He knows the nodding blue flower from which its fibres are made. He knows the wool of his cloak, how it’s shorn, spun, woven, carded, dyed and cleaned. If he picks up two stones and holds them in his hand he feels their weight. If he closes his fist on them he feels them grind against each other. If he looks at them they appear as different from each other as two people.

Shadows in a cave? He puts down the stones, looks back at Plato, who is still talking.

So Theophrastus had got what he wanted. He had made it to the Academy but nevertheless, these first days of his arrival in Athens couldn’t have been easy. Life must have been both the same and very different from how he had dreamed it would be: the stylized discipline, the lectures that were as much display as they were learning, the rhetoric, the theatricality of Academic performance, the elegant leisure, the heightened atmosphere, the emphasis on exercise of mind and body, the dining clubs.

The boys of his own age, those who were the children of Athenian citizens on both sides, were all doing their two years’ military training. He would have seen them, parading around in their cloaks and their newly instituted manhood. Known as the Ephebes, they lived in garrisons at Piraeus, received a wage of four obols a day and were taught how to fight with sword and spear, how to use catapults and how to shoot. Meanwhile, he was an outsider to all of that. So he sat in the Academy instead, listening to the ideas and the famous names arguing and wondered where to align himself. There was Plato, with his poetry and his entitlement and his former athleticism like a faint echo in the way he sat and the way he moved, holding court – should Theophrastus follow him? Or should he take a different tack? Should he follow someone more extreme, someone who was from outside, like himself, whose ideas were less elegant? Because, among the philosophers in Athens at that time, there were others whose thought was less abstract: Diogenes the Cynic, for example, exiled from his native town on the Black Sea, so it was said, for counterfeiting money. Nothing is left of his writings but his thinking was exemplified in the way he chose to live. The legend is that he lived in a barrel, or an amphora turned on its side, and he spent his days in the marketplace, deliberately shocking Athens by eating, shitting and occasionally masturbating in public. For this last offence, when called to account, he is supposed to have answered that he wished it were possible so easily to relieve hunger by rubbing the belly. Otherwise, he lived an ascetic life, routinely exposing himself to physical hardship in order to toughen himself up and routinely challenging his contemporaries for their moral and intellectual decadence. When the philosophers were dining, he would arrive dishevelled and stinking and pour scorn on Plato’s doctrine. ‘As Plato was conversing about Forms’, so the story goes, ‘and using the words “tablehood” and “cuphood”, Diogenes said, “table and cup I see but your tablehood and cuphood, Plato, I can no wise see”. “That’s easily accounted for,” said Plato, “for you have the eyes to see the visible table and cup but not the understanding by which tablehood and cuphood are discerned.”’

These are the types of conversation that the young Theophrastus would have witnessed, as he learned to eat and drink in the Academy style, reclining on a bench in a graceful manner, listening to the talk and to the music which punctuated it for entertainment. Athenian society was varied, sociable, stylized, ornate and tolerant. The whole pageant of eating was important, from the water brought in for hand-washing, in silver ewers, to the garlands of flowers for the guests’ heads. One directive went:

Be sure and have the second course quite neat,Adorn it with all kinds of rich confections,Perfumes, and garlands, aye, and frankincense,And girls to play the flute.

We know something too of what Theophrastus himself heard and thought, since among the writings of the Arabic scholars there are records of some of his own sayings. These too are very much later, probably written in Baghdad in the tenth century ad by Arabic Aristotelians, part of a cycle of texts called the Siwān al-Hikma, or the Vessel of Knowledge. Here we catch tiny glimpses of how these evenings with Plato went. ‘Theophrastus said that when Plato sat down to drink he would say to the musician, “sing to us of three things: of the First Good, of the secondary coming into being, and of the manifestation of things”.’ That is, sing of first principles, of their causes and of their manifestation in the world. So, the philosophical arguments and discussions weren’t limited to the daytime teachings of the Academy but went on far into the night.

All of this, for the young Theophrastus, was heady and exhilarating, but as might have been expected, there were also difficulties. However great Plato and the other thinkers might have been, Athenian society was both competitive and snobbish. Theophrastus was not an Athenian so he had no rights in Athens. Here he was a small fish, whereas on Lesbos he had felt big. He was inferior, a metic or resident alien, and, as such, he couldn’t hope to own property ever, or take part in the city-state’s democracy. He had to pay an annual foreigner’s tax. Whenever there were public processions, he had to walk with the other metics, carrying one of the special bowls that identified each one of them as outsiders. Besides all of which, he would not have spoken Attic Greek, but a dialect with an accent that betrayed his island origins. He learned fast. He learned to speak perfect Attic Greek and he was to spend all of his later life in Athens. But even with all of this, still something always gave him away. Bargaining, in his fifties, with a stallholder in the market, he was piqued by the old woman addressing him dismissively as ‘Stranger’. Something marked him out. ‘Stranger, it is not possible to sell these more cheaply.’ He was, and would always remain, less than an old market woman born in the city.

*

There was someone else who must have been immediately noticeable to Theophrastus, as he sat, meditating on his outsider status and wondering whose ideas to choose. There was another metic of great significance in Athens at this time – Aristotle, who came from Stagira in Chalkidiki, that little claw that reaches out into the Aegean at the top of Greece. In 355 BCE, Aristotle was roughly twenty-nine, so thirteen years older than Theophrastus and forty-four years younger than Plato. And in the hothouse atmosphere of the Academy, Aristotle was Plato’s favourite pupil.

Aristotle – what was he like? Not the name behind a monumental architecture of thought. Not just the symbol of an intellectual system, a system that can outlast millennia. Neither of those, but Aristotle the man, as he was then, with the itch of his great work still to do, making his way in the pride and din of Athens at its toppling peak, walking about the streets, and going to the dinners, and answering Diogenes or Plato with his own quick ideas. The Arabs preserved so much of Aristotle’s thought and tradition, and there are, among their writings, and in the Lives of the Philosophers (written, confusingly, by a different Diogenes), many descriptions of what Aristotle was like – but it is difficult to see a consistent, let alone a real person among the different accounts. He seems to have generated particularly strong and diverse reactions. Which to believe? Some are all idealization and mythologizing, some are almost savagely offensive. Aristotle was the kind of man who, for instance:

… was an avid reader of books and a prodigious worker. He shunned empty talk, weighing every word before answering a question. He liked music and preferred the company of mathematicians and logicians. He was a most eloquent man, a most distinguished author and, after Plato, the most eminent among Greek philosophers. At the same time he was a good man… displaying a genuine interest in the problems of his fellow men. He was modest, unassuming and considerate, and he was moderate in his habits and restrained in his emotions. Aristotle was fair, a little bald-headed, of good figure and rather bony. He had small blueish eyes, an aquiline nose, a small mouth, a broad chest and a thick beard.

Or, he was a trivial man who ‘tied his shoes in an extravagant fashion’ and ‘spent part of the day in the fields or by the rivers’.

Or, he was vicious and scornful and made money as a quack; a man physically ‘small, bald, stuttering, lustful and with a hanging paunch’.

Or, ‘his calves were slender, his eyes small, and he was conspicuous by his attire, his rings and the cut of his hair’.

Or, he was ‘white-skinned, a little bald, of small stature and strong bones, with small eyes, a thick beard, blue-black eyes, an aquiline nose, a small mouth and a small chest’.

Only sometimes, in the maze of words, is it possible to catch sight of a real person. Sometimes you can see him, as Theophrastus must first have done; like someone appearing momentarily among a crowd, for a split second he is looking straight at you – a man who is small, sparse-haired and with blue eyes of great penetration. Was that…? Over there, I thought I saw… Did you see? And then he’s gone. But there is something else – something that lasts after the crowd has swallowed him and he’s lost. His blue eyes, when they lock their gaze onto yours, are vivid with power: Aristotle is charismatic.

At any rate, Plato loved Aristotle for his quickness of mind, for his boundlessness and perhaps also for his difficulty, his refusal of intellectual control. He called him ‘the Reader’, or sometimes ‘the Mind’. According to the Arabic scholars, Plato habitually refused to begin his lectures if Aristotle was absent. ‘The audience is deaf,’ he would say, sitting in silence while his audience shifted. He would wait. And then only once Aristotle had appeared would he begin, saying as he did, ‘the audience is complete’, or, ‘begin to recite – the Mind is present’. So, to the young Theophrastus, Aristotle must have seemed a rising star, the man to watch, and of course, like Theophrastus himself, the Mind was an outsider.

But the Mind was restless. For his own part, sitting in the audience, listening, as he did every day, and feeling his thoughts turn, Aristotle must sometimes have felt frustration. He was young and, while Plato’s great work was done, his was still to do. It wasn’t so much his aims; they were broadly the same. His thinking was grounded in Plato’s, but increasingly now he found himself wanting to take a different direction. The ideal forms for instance – however much he loved and revered his master, he couldn’t make them fit his own understanding of life.

Didn’t anyone share his unease? Plato’s eager-faced disciples, just lapping it all up, complacent as cats, no questions asked.

But the world! The world was so fickle, so subject to change, so enthrallingly complex. What could it possibly have to do with something as static as an ideal form? And why not try to understand the nature of things as they are before looking for the essences they’d borrowed from elsewhere?

Plato’s lecture continued. His thought tended always towards the grandeur and dependability of absolutes. ‘If we are ever to know anything absolutely we must be free from the body and must behold the actual realities with the eye of the soul alone.’ So understanding is to be achieved only through abstraction, through pure definition. And all the time, although he started from the same place and with the same aims, Aristotle’s mind pulled in the opposite direction.

‘Wonder’ is what starts the philosopher off, Plato says, and there they are in agreement. Aristotle believed, as Plato did, that it was this feeling of wonder at the world that drove philosophical enquiry, and which might, in different men, have produced poetry, or myth. Indeed, in some of their predecessors, it had produced a combination of all three – such as Parmenides, an early pre-Socratic philosopher who explained the workings of the moon as ‘a torch which round the earth by night/Does bear about a borrowed light’.

‘It is owing to their feelings of wonder,’ Aristotle would later echo, ‘that men now begin, as at first they ever began, to philosophise.’ For ‘wonder is what a philosopher feels and philosophy begins in wonder’.

Both Plato and Aristotle use the word ‘thaumazein