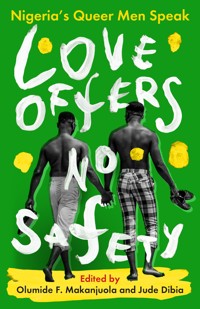

Love Offers No Safety E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Love Offers No Safety: Nigeria’s Queer Men Speak is a raw and powerful collection of 25 first-person narratives that explore the diverse experience of queer Nigerian men. These stirring stories cut across age, class, religion, ethnicity, family and relationships, offering a glimpse into what it means to survive as a queer man in Nigeria. From Tunji, who takes us back to the thriving networking community before social media, to Chukwori, who struggles to reconcile his need to serve God with his sexuality, and Abdulkarim, who frustratingly wonders if he’ll ever stop working twice as hard to be accepted, these stories are full of contradictions, anger, resiliency, profound insight, and radical hope. With heightened levels of oppression, violence, and discrimination faced by LGBTQ Nigerians due to the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Law, these voices remind us of what the queer community in Nigeria has always been fighting for - the freedom to be themselves, love themselves, and love each other, despite being viewed as unworthy. Love Offers No Safety is a heart-breaking yet hopeful reminder that love knows no boundaries and offers no safety, but it is worth fighting for.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Contents

Introduction

It is accurate to say that for many Nigerians, LGBTIQ people are tolerated only when they are media celebrities or ‘foreign’ and live outside the country. Once they are at home, living and breathing the same air the average Nigerian breathes, everything changes. So, watching the Netflix drama series, Sex Education with its openly gay Nigerian character who lives abroad but is on a visit and taken to a lavish and thriving underground queer scene gives the impression that although same-sex relationship is prohibited, there is room for queer people in Nigeria with a thriving culture to match. This is not just any culture but an enviable and glamorous one.

But we know better. We know the reality behind this alluring façade. It has been a little over nine years since the pernicious Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) was signed into law. In the intervening years since the law was signed, much has changed for LGBTIQ people in the country and attitudes are slowly shifting towards acceptance. In 2022, through the collective efforts of local LGBTIQ organisations and activists, the Federal High Court in Lagos delivered a judgement that declared S4(1), S5(2) and S5(3) of the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) as unconstitutional. Despite this, the LGBTIQ community has continued to, for decades, battle stigma, fear of physical and psychic violence, and unjust imprisonment. The introduction of the SSMPA strengthened and increased infringements on the rights of a community already under siege and denied so many things heteronormative society take for granted, especially the right to simply exist and be recognised. Instead, the existence of queer and non-binary Nigerians is either disputed or dismissed as being a result of Western influence or possession by evil, with the resulting impact being the silencing and distortion of queer voices and their lived experiences.2

We see this contestation of queer existence play out in different mediums, portraying itself to be the only acceptable truth. Early Nollywood movies like Emotional Crack and Men in Love peddled the idea that queerness was inherently evil and detrimental to society. In these movies, queerness was depicted as a self-chosen, anti-social behavioural trait, devoid of morals and completely at odds with Nigerian cultural norms. Emotional Crack tells the story of the destructive actions of a licentious queer woman who pursues a sexual affair with a married woman. Men in Love portrayed queer men as predatory, incapable of accepting boundaries or taking a no for an answer. It is implied that when queer men are unable to get their way, they sexually abuse and pry on the unwilling man, who is then inducted into homosexuality. And so, homosexuality must either be the direct result of a violating encounter or a life choice. These ideas about homosexuality are born out of ignorance, misinformation, and misrepresentation about the reality of queer people. Popular culture such as film, television shows and comedy skits then become pivotal in shaping, perpetuating, and reinscribing these negative perceptions of queerness as evil, degenerate and deviant.

While Nollywood is busying itself with creating negative narratives of queerness, the Nigerian state is also creating its own narrative by either legislating against or erasing the existence of LGBTIQ Nigerians from view. The Immigration and Refuge Board of Canada submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR):

[…]the Nigerian government reported that “[s]exual minorities are not visible in Nigeria” (Nigeria 5 Jan. 2009, Para. 76). In February 2009, while addressing the UN Human Rights Council Working Group to present Nigeria’s report, Nigerian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ojo Madueke declared that despite its best efforts, his government had been unable to find any gay, lesbian or transgender persons to consult on homosexual rights issues (Pink News 16 Feb. 2009; Vanguard 14 Feb. 2009; UK Gay News 16 Feb. 2009.) 3

This erasure of queer existence through denial, laws and popular culture reinforces hatred, false representation, and discrimination. The right to exist has become for many queer persons in Nigeria the existential crisis of a lifetime. This perhaps explains why many of the men in this narrative struggle with some form of depression and mental instability. However, by no means are all the stories contained in this collection deflating—far from it.

Queer men’s experiences are as complex as any other group within the LGBTIQ community. And often, their stories are glossed over by society, political and religious figures who want to downplay their existence and lived experience as part of safeguarding a misplaced notion of ‘tradition’, ‘societal values’ and ideas of masculinity. From how men should look and present themselves to the social responsibilities they must meet, these traditional norms and standards are expected of all men regardless of sexuality. As queer men, we must constantly navigate our sexuality around these models, limiting our ability to be fully ourselves and tell our stories. When we embarked on this project, it was important for us to speak with other queer men like us who wanted to tell their stories in their own words, without the fear of being judged. We were also keen on getting the perspective of a vast array of queer men, of different ages, socio-economic and educational backgrounds, religions, and ethnicities. We would have liked to have had the perspective of older men, especially those above 50 and even men in their 80s to give us a deeper perspective of queerness along the ages, but we were unable to find such participants. This does not mean that they don’t exist, but more because of generational differences, or they are living very closeted lives in heterosexual marriages. It could also be that older queer men are not regular users of social media or acquainted with the various mediums we used for communication.

We would have also liked to have heard from trans men and non-binary people, but we had no way of accessing these groups.

In our quest to identify suitable participants, we created a flyer which was distributed across different social media platforms and shared with key influencers and LGBTIQ organisations across the country. Through this process, we identified individuals willing to 4participate in the project and entrust us with their stories. We spent time capturing their early lives, relationships with their friends and families, careers, love lives, and the struggles they face as queer men, both within their immediate environment and in society at large. The stories were collected through one-on-one interviews conducted in their chosen safe space, always with the understanding that they reserved the right to withdraw at any stage of the process if they felt uncomfortable. While recounting their experiences, some contributors requested a timeout as they recalled painful memories. It became clear to us that many queer men are living with layers of traumatic experiences that left them broken, detached from their true selves, and forced to wear different masks to cope with themselves and the world around them.

We ensured that all the contributors who participated in the interview signed a consent form, which provided them with detailed information about the project, the importance of telling their story and the impact of being part of a collection of stories that is focused on the reality and lived experiences of diverse queer men in Nigeria in the 21st century. As expected, many had questions before signing the consent form and they include, but were not limited to, questions relating to security, available support for queer men in the country, why this was important to us and for them, the publishing process, and the potential impact of the book on the wider society. It was only after we had addressed all their questions and concerns that we began to record the stories of the brave men who chose to be part of this project.

The stories captured in this book reflect the experiences and views of the men as narrated to us. During the interviews, there were many recurring themes across all the stories: being queer, sexuality, religion, women, procreation, and acceptance. As to be expected, some of their views were contradictory and we have kept these contradictions within their narratives without attempting to resolve or edit them out because we were keen on capturing and preserving their truths, no matter how alarming and complex they appeared. The goal is that by allowing the readers to experience the stories as narrated by the men, a better understanding of the richness and breadth of their lived experiences is achieved. Further, we feel 5that presenting all the stories as they have been told humanises the narrators and presents an opportunity to further advance the discussion around masculinity, self-identity and most importantly, the expectations that come with being a man and the burden this brings for both queer and heterosexual men in Nigeria.

Many of the men we spoke to opened up about aspects of their lives which they had never shared with anyone before. We felt it was our responsibility to keep their stories safe and only use them for the purpose intended. The men had the option of using their real names or aliases and we encouraged anonymity as this will be safer for them and their associates. We debated on whether to distort or change landmarks and other identifiable locations mentioned to protect the possible identification of the contributors. However, the participants permitted us to keep these details, which in the end was a plus as we also believe this brings the everyday realities of such experiences closer to readers, especially those who may be familiar with these places.

From the onset, we understood that the lives and experiences of queer men were by no means monolithic. There were bound to be generational, regional, ethnic, educational, class and other differences that impacted and shaped their experiences as queer men. Hence why we felt it was necessary to capture stories that bridged these differences. We weren’t always successful in doing this as most of the men we interviewed were in their 30s. Still, the few men in their 40s allowed us to paint a broader picture of queer life from the 1980s to the present day. We saw how queer men were able to build a community during the pre-internet era, networking among themselves and supporting each other.

This is best captured in Tunji’s story, “The Past Was More Accepting Than the Future”. Tunji’s story brings a detailed and nuanced exploration of queer culture in the 1980s and 1990s to this book and provides some information that many may not be aware of today or have chosen to ignore, even within the community. From same-sex loving men who rendezvoused late at night at film houses in Mushin, Oyingbo, and Onikan areas of Lagos, to how gay men during this period understood social networking and community 6mobilisation for social celebrations in spaces they identified as safe. Tunji’s story illustrates that queer men had perfected a networking matrix of their own, long before social media and online connections became common, especially in major cities. In his story, Tunji reflected on the lack of awareness of HIV/AIDS in that era when queer men had sex without protection due to ignorance about safe sexual practices tailored for them. This ignorance was fuelled by health officials and policymakers who ignored our existence and chose not to include us in the growing HIV/AIDS campaign and advocacy of the time. One can sum it up by saying that in the recent past, there was a culture of silence shrouding queer existence in Nigeria which militated against directing awareness and service provision to the community. While the situation today is slightly different with increased visibility and attention, be it positive or negative, queer lived realities are still steeped in silence, denial, and erasure. This culture of silence has become the norm for many queer-related issues in Nigeria. It’s the equivalent of the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ mentality which several people still practice, as exemplified by statements like, ‘I don’t mind queer men, I just don’t want them in my face’. The function of such statements, even from people who claim they are not homophobic, is to silence us from the fullest expression of our identity.

Homophobia is a sub-theme that runs through many of the stories, which given the prevailing socio-political and cultural environment is unsurprising. Homophobia appears to be a thread woven into the fabric that makes up queer identity and expression in many countries, not just Nigeria. The inherited sodomy laws in many countries that were colonised by Great Britain reinforce homophobia and validate the social discrimination of queer people. In Nigeria, homophobic statements have been proven to result in actual violence against LGBTIQ persons because of the way they look, walk, or express themselves.1 Homophobia manifests itself through laws, policies, religious beliefs, and everyday social interactions. Queer people are expected to carry the burden of preventing homophobia by conforming to social expectations and roles in their everyday lives, a very unhealthy burden for our mental health and well-being.7

Queer Men & Visibility in Nigeria

Prior to the early 2000s, queer men’s reality and culture in Nigeria had limited visibility in mainstream social and political life. When they were visible, it was to highlight their degeneracy, contagion, and effeminacy. Although mainstream visibility was restricted, the LGBTIQ community cultivated a thriving underground visibility and interaction amongst themselves, even if this was restricted to a small circle of mostly queer men. Men who looked effeminate were generally presumed to be queer and for this reason, they became the yardstick for identifying queer men and they therefore experienced the brunt of homophobic violence.

Between 2005 and 2007, the conversations around HIV/AIDS and queer men were very limited and most people within the community did not think that HIV/AIDS was something they could get through anal sex. This was because HIV/AIDS prevention educational materials and advocacy focused heavily on heterosexuals and vaginal intercourse as the only mode of transmission. To date, there is still no national HIV/AIDS prevention material that specifically targets queer men, despite government support for multiple HIV/AIDS prevention programmes that are aimed at queer men or men sleeping with men (MSM)2. In 2009, after Nigeria conducted the Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance Survey in 2006-2007, a survey that was designed to access the risk behaviour and prevalence of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections amongst MSM, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS within the LGBTIQ community started receiving more programming and international donor funding attention.

While more attention was drawn to the HIV/AIDS prevalence amongst queer men who were tagged MSM in all the HIV/AIDS prevention programmes, the focus was on reducing the infection rate amongst these men by getting more people tested and providing condoms and, in some cases, water-based lubricants. This increased attention to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment in programme design did not translate into a focus on the human rights issues and social stigma experienced by queer men and the way these intersect to make them more vulnerable to the disease.8

Still, the discourse on HIV/AIDS at that time was important because it finally brought visibility to the sexual health of queer men. The opportunity created by those early discussions enabled queer men to question other human rights aspects such as the violence and discrimination against our community and the institutional violence within the healthcare system. While there has been a great level of progress achieved in providing HIV/AIDS prevention education and treatment services, the interlink between human rights and social issues experienced by queer people was not part of the programme design.

The HIV/AIDS conversation also brought an awareness of queer men and LGBTIQ rights discourse to a wider audience, even if the community was reduced to disease and contagion. Much of the discourse took place online and was mostly controlled by voices that were already biased against LGBTIQ people. By the mid-2000s, as the internet and social media became more widely available, queer people started using social media to create platforms that spoke to their issues, tell their stories, and expand the discussion on LGBTIQ rights beyond the moralising heteronormative imposition of disease, effeminacy, and degeneracy. Through opportunities created with social networking sites such as 2go, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, queer men’s life experiences could no longer be ignored. News outlets and blogs relayed information on most queer issues directly through what people had posted, said, or done on their social media handles. Thus, the awareness created by the HIV/AIDS discussion enabled more queer men to leverage the growing social media space and the internet to create a more balanced picture of themselves and their world.

The growing social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram gave way to alternative narratives that put the spotlight on the diverse experiences of queer men across Nigerian cities. It captured the fullness of the community and provided a platform for people to share their lived experiences of joyful moments, self-expression, violence, stigma, isolation, and family rejection amongst others. From having next to no visibility to witnessing the transformation and power of social media being leveraged to create their own stories and voice, queer men were now controlling 9their own image. This shift created many online platforms such as kitodiaries.com3, Nostrings4, Rustin Times5 and many others which now focus on expanding queer men’s narratives by capturing the day-to-day experiences of queer people and happenings around cities in Nigeria. One of the most interesting aspects of this advanced visibility is how through these platforms, queer men were able to share their stories of blackmail, extortion, and other related forms of attack to ensure others do not fall victim in turn. In advancing this even further, Kito Diaries, for example, created a kito6 section on their platform where people could share stories, pictures and information about blackmailers who targeted queer men for mob violence.

The visibility of queer men since the early 2000s till date has changed and we are seeing a generation of digital natives who are using social media to create platforms to express themselves, share and talk about what matters most to them through their real or anonymised identities. Online, many queer men do not have to worry much about who they are visible to as they can limit the identifying factors they choose to share with the online community while still contributing to the larger advocacy and visibility of queer stories and experiences. This has enabled greater visibility of and collaboration amongst queer men. This sharing of experiences is important because by increasing the understanding of the diversity of queer men, their lived experiences and their engagement with their society, stereotypes of what queer men look, talk, or behave like are debunked. In the last few years, the impact of this exposure has engendered more diverse discussions around masculinity, social norms, religion, and other social barriers that limit how men express themselves. The public expression of people like Denrele Edun, James Brown, Bobrisky, and Denola Gray as androgynous and gender-fluid persons have contributed greatly to challenging norms of masculinity in a way that has triggered discussion around manliness in Nigeria. Some people love these diverse and gender-disruptive men and are grateful to them for being themselves. Our narrator in “I Was Forced To Come Out” articulated his appreciation for Denola Gray and Denrele Edun for their confidence in expressing themselves through fashion and gender-bending 10expressions within an unforgiving society like Nigeria. However, these same people have been subjected to hate speech and online bullying simply because they have chosen not to conform to the societal expectations and conventions surrounding manhood and masculinity. Apart from expressing themselves freely through their fashion styles, they have also provided an alternative idea of who a man should be and what a man should look like. It must be stated clearly that while none of these men have self-identified publicly as a member of the queer community, they have contributed to shifting the discussion around gender expression, roles, and expectations.

It is important to mention that the visibility and discussions created through online advocacy has birthed a new generation of activists and advocates who are now using their voice to advance the LGBTIQ discourse across Nigeria. While we are still living with the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act and other discriminatory laws that must change, we have seen how online spaces and platforms have enabled queer people to engage and push alternative narratives, especially those that are aimed at shifting social perceptions of our community. Social media has therefore accelerated social acceptance, inclusion, and human rights protection. This change also means that many people do not need to formally be part of an organisation before contributing to the wider advocacy work being done by organisations across Nigeria. These are some of the results of increased queer visibility but also a reminder that this community cannot be silenced, by law or social norms and practices.

Emerging Themes

Familial & Societal Acceptance

In any society, most people want to be accepted, have autonomy, and have their power of choice respected, and queer people are no different. This means that while civil laws and policies on personhood may change, queer people the world over must work extra hard to gain acceptance from families and friends who still hold on to their heteronormative views and gender role expectations even in societies where the law recognises and upholds the humanity 11of queer people as it is the case in places like South Africa.

In this book, our contributors reflect on their individual journeys of acceptance or non-acceptance as is often the case. While some of the men who narrated their stories are already supported and accepted by their families and friends, most remain doubtful if that will ever happen to them. One thing that was common and frustrating for many of the contributors is the idea that given their economic contribution to their families and society at large, to have to work extra hard for acceptance is both unfair and unjust. As Abdulkarim notes in “My Sexuality Is Part Of Me But Does Not Define Me”, ‘I have a good job and I contribute to society. Why can’t people mind their business? Why can’t I be accepted for who I am? What kind of threat does a person like me pose to society?’

In 2020, many young people across the country took to the street to protest the relentless police brutality, discrimination, and targeted attacks by a special branch of the Nigerian police called the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). Protesters offline and online using the hashtag #EndSars, shared their experiences of violation by law enforcement officials who targeted and criminalised them for simple acts such as wearing their hair in dreadlocks, or for possessing expensive smartphones and other items that the police consider to be symbols of wealth or an illegal lifestyle. LGBTIQ activists, advocates and community members joined what became the ENDSARS protests.

One would have expected that given the context of the protest, most Nigerians had finally attained a greater understanding of universal human rights, especially when it comes to their fellow youths. This was not to be the case. The massive fault lines that appeared when LGBTIQ persons started sharing their experiences of brutality was shocking to many in the community. LGBTIQ persons were told to not make the protest about them as it was not the right time to raise their voices, share their experiences of police brutality or even join the protest at all. The ENDSARS protest provided an opportunity for the LGBTIQ community to resist police brutality just like other young Nigerians who had for long invalidated their experiences and existence. The boldness of the community to join 12such a mainstream protest, waving the rainbow flag and speaking up about how police brutality had affected the community and how young queer people are more vulnerable to police brutality was a milestone in the LGBTIQ movement that should never be forgotten. It wasn’t just about the community pointing out the targeted police brutality they experienced but showing up as LGBTIQ persons and queering the public space by reclaiming it as a space that also belonged to them. This was a great moment in the history of LGBTIQ in Nigeria, not to mention the key role queer people played behind the scenes of the ENDSARS protest.

While the ENDSARS protest may be considered a defining moment for the LGBTIQ movement in Nigeria, the experience also served as a timely reminder of the erasure, discrimination, and disregard for queer people’s life, even in the face of shared youthful experiences. A movement that should have brought all Nigerian youths together became a movement that recognised only one type of sexual identity, heterosexuality. The so-called soro soke generation—when it came to sexual identity—still firmly worshipped at the altar of social conformity and heteropatriarchal normativity. Despite this attempt at erasure and disregard for queer voices, Nigerian queer men and women came out to protest and were determined to assert the importance of their humanity and existence, showing that they will not go quietly into that bloody night at the Lekki Toll Gate or across all the places the protest was happening in Nigeria.

In the last few years, even though social acceptance and support for LGBTIQ issues is on the ascendency, its impact remains low when compared to the realities faced by queer people. The 2015 social perception survey on Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual persons commissioned by The Initiative for Equal Rights (TEIRs) and conducted by NOI Polls7 show that only 11% of Nigerians polled will accept a family member who is lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Of course, this had increased to 13% in 2017 and 30% in 2019, a phenomenal increase when compared to 2015 and 2017. The increase in those who will accept a family who is lesbian, gay, or bisexual can be attributed to the social advocacy work of many local organisations and the increased visibility of the LGBTIQ community across the 13country. While this result is an improvement, many queer people continue to struggle with acceptance from their families and often, those who are accepted face the additional burden of maintaining that acceptance.

For many of the men here, familial disenfranchisement is a constant threat to their experience of—and identity as—queer men. The fear of the loss of familial support is most impactful amongst young people who are still dependent on their families for accommodation, school fees, and other welfare needs. For the older queer men, the situation is reversed as they become burdened with the responsibility of providing financial support for their families in exchange for acceptance. This emotional blackmail is an example of how even social and financial achievements are not enough insulation from bigotry and exclusion because society continues to place higher moral standards on queer people than on any other group.

While the pursuit of acceptance is important for many queer men, there are still some, who after self-acceptance, remain scared of coming out to their families and friends. For them, identifying as queer will hinder how they are seen or related with. This fear is real for many of the contributors, as can be gleaned from Farouk’s statement in “I Am Queer”, ‘This is who I am, and I cannot deny the fact. I have accepted it, but I cannot totally welcome it as it will be catastrophic to come out and openly declare it. Some of my friends and family members know about it and they are mostly not happy with it.’

Many of the contributors expressed hopelessness with the situation. ‘I don’t think there’s anything that can be done in Nigeria to make a gay person feel free or accepted in the future. If same-sex relationships cannot lead to marriage in Nigeria, normal association itself cannot be accepted. My hope for the future is to be able to cater fully for my family, myself and to be empowered enough to assist other people,’ says Mohammed A in his account, “Swinging Both Ways with A Solid Marriage”.14

Homophobia, God, and Religion

It did not come as a surprise that many of the men we interviewed mentioned ‘God’ and their relationship to religion, faith, and spirituality. Nigeria is one of the most self-avowedly religious countries in Africa and almost all aspects of social and political life are influenced by religion, specifically the Abrahamic religions - Christianity and Islam. Some of the narrators struggled with the idea that being queer was sinful and against God’s wishes, though some saw no conflict between their sexuality and religious beliefs.